13 minute read

HEALTH

Can Psychedelics Make You Whole?

An unconventional treatment for severe trauma By Danielle Berrin

Advertisement

Samantha rose stein had been on the ascending arc of her career as the director of special projects for TechCrunch, an online media platform reporting on high tech and startups, when, as Joan Didion famously put it in The Year of Magical Thinking, Stein’s life changed “in the instant.”

A fixture in Silicon Valley, Stein frequently traveled overseas to helm Startup Battlefield, a global competition run by TechCrunch in which early-stage startups are invited to compete for prize money as well as the attention of media and investors. The role placed Stein, who is Jewish, in a vaunted position, able to anoint the next hot startup in one of the most lucrative industries in the world.

During the summer of 2018, while on a work trip in Beirut, Stein was violently assaulted. She declined to share details but said that the episode triggered a post-traumatic stress disorder so paralyzing that she was unable to leave her house.

“I experienced a living death,” Stein, 33, said when we sat down together in the courtyard of her hotel during a visit to Los Angeles last November.

After the assault, Stein had difficulty sleeping and exercising. Her appetite decreased. She suffered from nausea, nightmares and panic attacks and was diagnosed with clinical depression. For months afterward, she avoided socializing even with her closest friends. “I became a ghost of myself. Nothing brought me joy or pleasure,” she said.

Stein threw herself into the pursuit of a cure. She tried an array of therapies, from the cutting-edge to the traditional: cognitive behavioral therapy, trauma therapy, sound healing and mindfulness practice, among others. When those didn’t work, she took prescribed pharmaceuticals. Stein was fortunate to have the means to shell out tens of thousands on her healing journey, but what did it matter when nothing was helping?

Informed by her professional role identifying breakthrough companies, Stein decided to interview PTSD experts about breakthrough therapies. That’s how she was steered toward an unconventional treatment: psychedelic-assisted therapy. This protocol combines the use of psychedelics—a class of drugs able to induce altered thoughts and sensory perceptions—with talk therapy. “I was super resistant at first,” Stein said. “You don’t want to feel more altered when you’re already altered.” But she was desperate.

Stein is now among those who claim that a handful of psychedelic-assisted therapy sessions was transformational, enabling her to confront her trauma and heal her wounds.

“I don’t think I would be where I am today or who I am today without psychedelics,” Stein told me. “I credit these therapies with bringing me back to life.”

Psychedelic drugs—including MDMA, the drug known as “ecstasy,” and psilocybin, the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms”—are still illegal in the United States, classified by the federal government as Schedule I, meaning they have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. But a network of clinicians has been researching and administering them nonetheless.

Over the last decade, research in psychedelics has undergone a renaissance thanks largely to the advocacy work of MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. The nonprofit, founded by Rick Doblin, who is Jewish, promotes and funds psychedelic research in the United States and other countries, including Israel, which has become a leading center for this area of study.

As a result, psychedelic-assisted therapy has gained the imprimatur of prestigious research institutions, including Johns Hopkins, Stanford and Yale, which are helping to rebrand substances once thought to

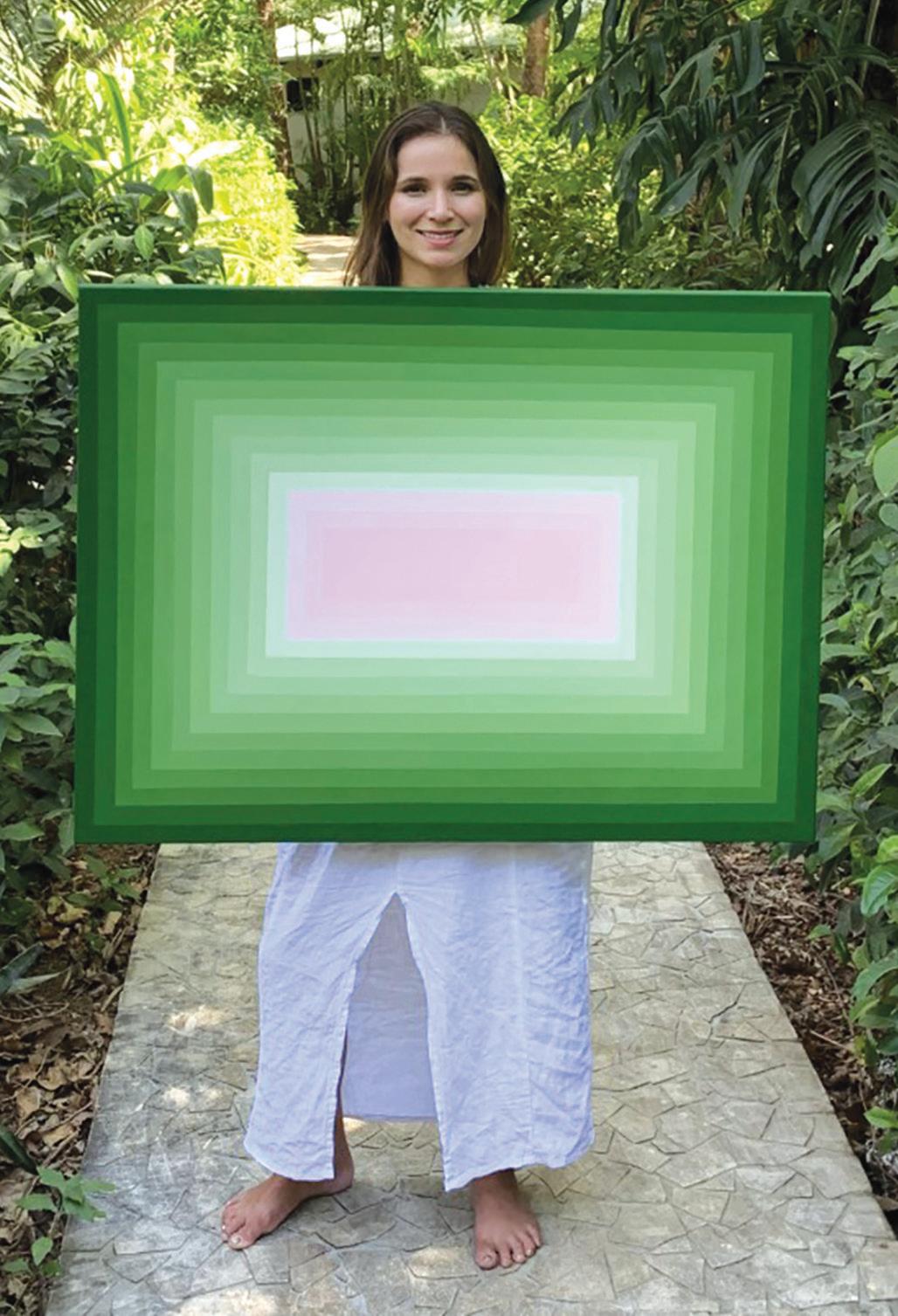

Samantha Rose Stein

zap your brain as life-saving medicine.

The investment in psychedelic science has contributed to a softening legal stance on Schedule I drugs, particularly at the state and municipal levels. Across the United States, a handful of bills and ballot measures have passed to decriminalize psychedelics or approve them for use under licensed practitioners.

And pop culture is—once again— digging psychedelics. A recent article in Town & Country magazine declared, “America’s intelligentsia is in the grip of a hallucinogenic fever dream.” The Hulu television series Nine Perfect Strangers was seen as a de facto advertisement for microdosing after a wellness guru played by Nicole Kidman administered psilocybin to her patients.

Though research is ongoing, studies suggest that psychedelic therapy can treat the most stubborn forms of depression and PTSD—and with far more compelling results than traditional treatments such as antidepressants. MDMA, the substance most commonly used in this treatment, has proven so effective at treating PTSD that it’s on track to receive FDA approval for use in therapeutic settings as early as 2023.

And yet, some say that evaluating psychedelic-assisted therapy through a purely clinical lens is to miss something critical about its holistic—or even spiritual— power. “Conventional mental health treatment has done a pretty terrible job of incorporating spirituality into therapy, even though it is so important to most people,” said Rachel Yehuda, an Israeli-born professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the ICAHN School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and director of its Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research. “Many people report having a spiritual experience with psychedelics, and, you know, I wouldn’t be surprised if that was part of its therapeutic efficacy.” (See sidebar, page 32.)

Yehuda has focused her clinical work on PTSD and trauma since 1987. She’s worked with veterans and Holocaust survivors, among others, and is considered a pioneer in the study of epigenetics, the effect of environment on gene expression, and the intergenerational transmission of trauma. She became interested in psychedelics after watching veterans suffer from PTSD for decades, even as they were being treated with antidepressants and psychotherapy, which, Yehuda said, yielded only marginal benefits.

After hearing repeated whispers of an “almost miraculous treatment,” Yehuda recalled, she decided to go to Israel to train in psychedelic-assisted therapy. The country has been on the leading edge of MDMA research since 1999, when MAPS hosted a symposium in Israel on using that drug to treat PTSD. With the support of Israel’s Ministry of Health, MAPS has funded an Israeli research team in evaluating MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, now in phase III trials.

It may be Israel’s unique circumstances that primed it for psychedelic experimentation. “In Israel, PTSD is a real societal challenge because everybody goes to the army and because the conflict is very present for everyone,” said Keren Tzarfaty, executive director of MAPS Israel and a clinical investigator in Israel’s trials. “Both Palestinians and Israelis exhibit much higher than normal levels of PTSD, which is one of the most difficult conditions we can endure as humans.”

Israel’s clinical trials take place in a hospital setting where every step of the process is overseen by a medical professional. Over the course of several months, patients will undergo three MDMA-assisted sessions, each one bookended by intensive talk therapy, both to prepare patients for the

psychedelic experience and to help them “integrate” their experience afterwards.

“Sixty-eight percent of our participants do not suffer from PTSD a year after treatment is over,” said Tzarfaty. “Those are numbers you cannot find in any other modality of clinical work.”

These recovery rates explain why the scientific and mental health communities are so excited about these old-new drugs. If clinical trials continue to demonstrate that patients experience relief or recovery with a finite number of sessions rather than depending on a lifetime course of antidepressants, the mental health field could undergo a radical transformation.

As Yehuda put it, “Participants in this research don’t just say, ‘My symptoms are better.’ They say, ‘I have my life back.’ They talk about being able to function better in the world. That’s more than just symptom reduction and it’s very, very promising.”

JEWISH ‘PSYCHONAUTS’ TAKE A SPIRITUAL, GUIDED TRIP

“Today feels like a coming

out,” declared a panelist at the inaugural Jewish Psychedelic Summit—likely the first event of its kind—which was held on Zoom in May of last year.

Organized by Rabbi Zac Kamenetz, journalist Madison Margolin and Natalie Ginsberg, the policy and advocacy director of MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, the summit convened more than 1,500 Jews of varying backgrounds—from Orthodox to Buddhist-leaning “JewBus”— to discuss the connection between Jewish spiritual tradition and mind-altering substances. Though the atmosphere was celebratory, the subtext was clear: Even though psychedelics have been illegal for personal use in the United States and Israel for nearly half a century, an underground Jewish subculture has been using them anyway, exploring how altered states of consciousness can deepen and diversify Jewish life.

“There’s something about direct religious spiritual experience that I believe is at the heart of Jewish existence,” Kamenetz, founder of Shefa: Jewish Psychedelic Support, told me during an interview.

Kamenetz, 40, who lives in Berkeley, Calif., wasn’t always a “psychonaut,” a term coined in the 1970s to describe those who induce altered states of consciousness to explore the unconscious mind. He grew up in Southern California in a secular Jewish family in which there was no conversation about spirituality or the Divine.

It wasn’t until Kamenetz attended high school in Israel that a visit to an archaeological site sparked something extraordinary. “I had a very powerful, unexpected, endogenous, overwhelming mystical experience,” he recalled. “I knew God was real.” He immediately went out and bought a kippah and became an observant Jew.

A decade later, Kamenetz was serving as rabbi of the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, but the magic of that mystical experience had begun to wear off. He decided to join a Johns Hopkins University study that was seeking clergy to participate in research focused on psychedelics and spiritual leadership.

It was the first time he had tried psychedelics, and the experience changed him. There was only one problem. “The protocols for the experience were created by people who do not necessarily have Jewish cultural, spiritual and psychological needs in mind,” he said.

To meet that need, Kamenetz created Shefa, an organization that offers routine private “integration circles” in which Jews can process psychedelic experiences within a Jewish context that includes storytelling and learning Jewish texts.

At a time when younger generations of Jews view traditional synagogues as stale or out of touch, proponents of psychedelics say that the drugs offer a way to reclaim the Jewish mystical tradition. For some, psychedelics can imbue Jewish rituals and holidays with enhanced power. For others, they’re a chance to explore collective Jewish trauma or open a portal into a deeper realm of mind, advocates say.

“This is going to inspire a creative, spiritual renaissance that puts the Jewish people back in touch with that burning core that sits at the heart of our mystical tradition,” Kamenetz said.

To that end, Shefa is launching a program to train rabbis in how to talk to congregants about their psychedelic experiences and integrate their insights into Jewish practice.

But what Kamenetz envisions is yet bolder: He sees psychedelicinspired creativity radiating to all aspects of the Jewish experience, producing new rituals, texts and music.

“This is about rewiring ourselves in some essential way,” Kamenetz said. “For increased connectivity, friendship; for a greater sensitivity to existence and our role in it.” —Danielle Berrin

Rabbi Zac Kamenetz at the Johns Hopkins University study

Tzarfaty said she has already seen a major shift in the perception of psychedelics among the Israeli public. When clinical trials began in 2011, Tzarfaty said, the stigma associated with both psychedelics and mental health treatment made it difficult to find participants. But as word got out about the effectiveness of the therapy, more and more came seeking treatment.

A decade later, what began with a handful of patients has expanded to a waiting list with hundreds of names. Public demand for psychedelic care prompted Tzarfaty to propose to the Ministry of Health an expansion of the country’s treatment capacity, and, in 2019, Israel’s government became the first in the world to approve a Compassionate Use Program for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, allowing an additional 50 Israelis to receive treatment outside of clinical trials. Israel’s government is funding half of the program, with additional funds supplied by the United Statesbased Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation.

Despite the promising results, even true believers caution against psychedelics evangelism. “I’m someone who thinks we still have a lot of work to do,” said Yehuda, the trauma specialist. As director of ICAHN’s psychedelics research, she will soon be advancing her own clinical trials, including a study examining the impact of psychedelics on intergenerational trauma.

“People are getting very excited about the trials that are out there, as they should be,” she said. “But before we upend our entire clinical practice, we want to be sure. We want to understand, for example, who shouldn’t be given these treatments.” Yehuda is also concerned that people will put too much emphasis on taking psychedelics and too little on the therapy. “The process of preparation and integration are critical,” she said.

And then there’s also the hurdle of history and politics: The war on drugs, beginning in the 1970s, badly damaged the reputation of psychedelics. It was around this time, when these substances were designated as Schedule I, that studies came out implying that psychedelics could have negative effects on the brain, such as a link between MDMA and serotonin neurotoxicity, which could impair memory. But more recent studies, including one published in Frontiers in Psychiatry in 2022, show that these negative effects occur when MDMA is used in combination with antidepressants, which can lead to a rapid rise in serotonin concentration in the central nervous system. This is why, Yehuda said, more research is necessary to determine who is at risk.

For Samantha Rose Stein, the tech professional whose life was in ruins after an assault, psychedelics provided salvation.

“At this present moment, I have greater self-acceptance, self-love and self-awareness than I’ve ever had before,” she said, “and that’s something I gained through this healing process.”

But when I asked Stein if she considers herself cured, she demurred.

“We’re human,” she said. “We’re constantly changing. I don’t want to promise a ‘cure’ and disappoint anyone. Healing isn’t binary; sick or well, healthy or unhealthy. There’s a continuum of these things.”

She did say that she no longer feels the need for MDMA sessions, though she is still pursuing other alternative therapies. Most recently, she has undergone ketamine therapy, another psychoactive experience going mainstream in cities like New York, Miami and Los Angeles. Ketamine is a fully legal, FDA-approved anesthetic often used in emergency rooms. At high doses, and when delivered intravenously, it has been shown to have reparative effects on the brain.

Now, Stein wants to help others access the healing she found so restorative. She is currently at work on a book that she described as a “how-to guide” for psychedelic-assisted therapy. She is also a deeply committed artist and has presented her paintings at Art Basel Miami. She no longer works in Silicon Valley but said she continues to invest in startups.

“I think of myself as less attached to a particular job or person or place,” she said. “It’s a life mission I’m attached to, and that mission is maximizing people’s ability to access and understand breakthrough therapeutics for healing, for cultivating a whole self.”

Rachel Yehuda

Danielle Berrin is an award-winning journalist based in Los Angeles.