26 minute read

A Diverse Jewish Story

from March/April 2023

by HadassahMag

Advertisement

Insights from memoirs, histories and guides |

By Diane Cole

Aprayer shawl of many colors enfolds today’s Jewish community, a population that, like America as a whole, is increasingly diverse. The Pew Research Center study “Jewish Americans in 2020” reported that 15 percent of those aged 18 to 29 also identified as Black, Hispanic, Asian, multiracial or other ethnicity. The study additionally found that among American Jews 30 and under, 29 percent are members of households that include one or more individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, multiracial or other ethnicity.

Given these numbers, it is hardly surprising that Jewry’s multicultural mix has brought forth a plethora of books that describe that diversity. Recent offerings include memoirs such as Marra B. Gad’s The Color of Love and Nhi Aronheim’s Soles of a Survivor and histories like Once We Were Slaves by Reed College professor Laura Arnold Leibman. There are Speaking of Race, a how-to guide from journalist Celeste Headlee, and an essay collection titled The Racism of People Who Love You from Samira K. Mehta, a professor of women and gender studies as well as director of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Colorado Boulder. Taken together, these volumes provide a welcome entrée into engaging in tough conversations around the differences as well as the similarities among Jews today.

Engaging Narratives Books offer entryways into tough conversations and reveal the past through multiracial Jews like Sarah Brandon Moses and Isaac Lopez Brandon (in painted miniatures, top and middle row) and the present, in works from Marra B. Gad (top row, left), Celeste Headlee, Nhi Aronheim (top row, right) and Samira K. Mehta (bottom row).

But is the composition of today’s American Jewish population that different from past generations? Far less than you might imagine, according to Leibman. In Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multi‑ racial Jewish Family (Oxford University Press), she traces the roots of wealthy New Yorker Blanche Moses, a descendant of one of the oldest and most prominent Jewish families in the United States, to the 18th century Black and Jewish communities on the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Suriname.

Starting with objects passed down through the generations—two painted ivory miniatures of Moses’s ancestors, Sarah Brandon Moses (1798-1829) and her brother Isaac Lopez Brandon (1793-1855)—Leibman unravels the family’s stories. Both Sarah and Isaac were born “poor, Christian and enslaved,” Leibman writes. Although their father, Abraham Rodrigues Brandon, was one of the wealthiest and most influential Jews in the Sephardi community in Barbados, their mother—Abraham’s common-law wife, Sarah Esther Lopez-Gill—was of both white and African ancestry and was born enslaved to a Christian household.

Moreover, Leibman notes in the book, “Sarah and Isaac were not the only people in this era who had both African and Jewish ancestry. The siblings’ story reveals the little-known history of other early multiracial Jews, which in some of the places the Brandons lived [in the Caribbean] may have been as much as 50 percent of early Jewish communities.”

What distinguishes the story of Sarah and Isaac, Leibman writes, is their father’s wealth and ambitions for his offspring that offset many of the challenges they faced because of their mixed heritage. His influence in the Caribbean Jewish community smoothed the children’s conversion to Judaism and their eventual acceptance in the local congregation, which he headed. He helped pay for their freedom and, just as important, brought them to England and guided their entrance as white Jews into the Jewish communities of Britain and the United States.

Sarah eventually met and married Joshua Moses and moved to New York City. When her brother applied for American citizenship, he similarly had no difficulty meeting the require- ment that he be a free white man. Over the decades that followed, their origin story gradually faded into obscurity.

Alas, so did the stories of other Jews of mixed race ethnicity, resulting in the history of the Black Jewish experience becoming mostly invisible, writes Leibman. This absence feeds the mistaken assumption that a person whose skin color is not white is also not Jewish.

Leibman cites instances throughout the 19th century and later when Jews of color were confronted in American synagogues about who they were and why they were there.

“Prejudice is also part of the story of American Judaism,” Leibman writes in the prologue to Once We Were Slaves. “I hope by recognizing that past we will continue to move forward toward a more equitable and inclusive future.”

Bias in the jewish community is brought to the fore in Marra B. Gad’s powerful memoir, The Color of Love: A Story of a MixedRace Jewish Girl (Agate Bolden). Born to an unwed white Jewish mother and an unnamed Black father, Gad, an independent film and television producer in Los Angeles, was adopted by a Jewish family in Chicago as an infant.

“In the Jewish community, there has always been some level of confusion around the nature of my brown existence—especially around the notion that I was born a Jew and that I did not convert to become one,” she relates in her book. “To this day, I am routinely asked when I go to syna- gogue if I am ‘in the right place.’ I am assumed to be ‘the help’—the kitchen help, someone’s nanny. Rarely am I simply welcomed with a smile like my Eastern European-looking family members.”

Enveloped by a loving and supportive family growing up, Gad writes about feeling nurtured by her family but confused when subjected to the racism of others because she is biracial. In The Color of Love, she recounts stories about Jews who couldn’t believe she was really Jewish and about members of the Black community who regarded her as not Black enough.

There were neighbors and strangers alike who puzzled over why she did not have the same skin color as her parents and “nice Jewish boys” who wouldn’t date her because, they told her, they wouldn’t know how to explain her to their parents.

The cumulative impact of this

Magazine Discussion

Join us on Thursday, March 16 at 7 PM ET as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein moderates a discussion that will explore issues of identity and belonging that have motivated a growing number of Jewish women of color to write about their experiences. The program will feature Celeste Headlee, a Black and Jewish award-winning journalist, radio host and author of Speaking of Race ; Samira K. Mehta, a professor of women and gender studies as well as Jewish studies at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of the recently published The Racism of People Who Love You ; and Emily Bowen Cohen, a Jewish Native-American artist and writer whose graphic novel for children, Two Tribes , will be published later this year.

This event is free and open to all. To register, go to hadassahmagazine.org constant scrutiny of her appearance and the questioning of her belonging “warped the lens with which I viewed myself,” she writes.

What helped sustain her, how ever, was her belief “that we are all born as loving beings” and the deter mination that she could not respond to other people’s hatred with more hatred. “I stand with two feet solidly planted in love,” she writes. “Because I know what it is to be deemed un‑ worthy and hated because of my skin color and because of my religion. And because I will not be an instrument that puts more hate into the world.”

There are many multicultural paths to Judaism. Nhi Aronheim’s is, perhaps, among the most distinct. Today she lives in Denver, where she is a longtime member of Hadas sah and where she and her family are part of a Conservative Jewish com munity. She was born in the 1970s, however, in a very different world, in

Creating A Warm Welcome

Award-winning journalist, radio host and author Celeste Headlee is often approached to discuss bias, discrimination what was then South Vietnam, and grew up in poverty in the slums of Ho Chi Minh City, as she relates in her memoir Soles of a Survivor (Skyhorse Publishing).

The book describes how, at the age of 12, without her family, she made a perilous escape that took her through the jungles of Cambodia to a refugee camp in Thailand. She lived there for two years until she qualified for refugee status and came to the United States, where she was adopted as a teenager by a Christian family in Louisville, Ky., and began to assim ilate into mainstream American culture.

She faced another kind of accul turation when, after she finished col‑ lege and began a successful career in telecommunications, she met her hus band to be, Jeff, who is Jewish. When he asked her to consider converting, together they visited a variety of syn agogues and chose one where, even and how to communicate about potentially difficult subjects. Her TEDx talk “10 Ways to Have a Better Conversation” went viral and has been viewed over 34 million times. In her latest book, Speaking of Race , she draws on research on bias and communications to give practical advice on how to navigate the hard discussions that crop up around our racial divisions. Headlee, who lives in the Washington, D.C., area, offered via email a few suggestions, edited for brevity, for making Jews of color feel welcome in Jewish spaces. though she was the only Asian face in the sanctuary, she felt welcomed and accepted by the other members. The rabbi, however, treated her wish to convert with skepticism and encour aged the couple not to join.

What are some common issues that Jews of color experience in synagogue?

After they were married, Aron heim and her husband returned for a second interview with the rabbi after which he agreed, still somewhat grudgingly, to oversee her conversion and affirm their synagogue mem bership. “The process of conversion was challenging,” she writes. “It’s difficult for most people, but it was particularly difficult for me, an Asian woman adopted into a Christian household.”

Despite those difficulties, like Gad, Aronheim chooses to focus on love.

“Now I relish being a Vietnamese Jew,” she writes, noting the impor tance of radiating “goodness to those we meet” regardless of their religion and background.

One is that people don’t look at you when you go into the synagogue. They’re avoiding eye contact. That’s partly because people are afraid to get into a conversation that might involve race. But it exacerbates the problem in that it makes that person of color feel othered and not welcomed.

Another is asking “What brings you here?” As though it’s odd that you’re in a synagogue, or that you don’t belong there. Any question that implies in any way that that person does not belong there or doesn’t know what they’re doing is probably a question that is not inclusive.

What’s the best way to apologize if one’s behavior or words are seen as insensitive?

This is a great question. One of the reasons it’s so great is that you will make mistakes. There is no way that any of us can know everything there is to know about other cultures, so at some point we’re going to stick our toe over the wrong line.

The number one thing to do is make no excuses. Simply say, “I’m sorry,” without justification, without an explanation.

Even if all they do is give you a look, you can say, “By the look on your face it sounds like I said the wrong thing. I’m so sorry if that’s true.”

The next thing is to identify what it is that you said wrong, if you know what it is. Then ask for and welcome any feedback to help you understand how to avoid such errors in the future.

—Diane Cole

Two important new essay collections answer questions around how to navigate and talk about prejudice, both in the Jewish community as well as the larger society.

Award-winning journalist Celeste Headlee frequently addresses the topic both in her writing and as president and CEO of Headway DEI, a nonprofit that consults on diversity issues for journalists and the media.

Her background, she notes in her most recent book, Speaking of Race: Why Everybody Needs to Talk About Racism—and How to Do It (Harper Wave) gives her a unique perspective.

“Because I am a light-skinned Black Jew, sometimes called ‘racially ambiguous,’ I’ve been talking about race for as long as I can remember,” she writes. In thoughtful, careful detail, interspersed with anecdotes from her own life and the people she has met, she breaks down fraught racial issues. Emphasizing the importance of having conversations, “lots of short, low-stakes conversations,” she gives examples of strategies and techniques that will help foster calm, productive dialogue.

“The truth is that everyone is biased. Everyone. We all make assumptions about people based on superficial observations,” she writes in the forward. Her book is intended to help readers “recognize that you can disagree with someone strongly and yet have the conversation anyway. Debates have changed very few minds, but conversations have the power to change hearts.”

In an email interview, Headlee talked about some of the biases in the Jewish community and the importance of being more sensitive and welcoming to Jews of color. She counseled synagogue members to embrace Jews of color wholeheart- edly. “Show them that you are happy to see them,” she said.

“That’s how you include that person in your service. Don’t instruct them or teach them how the service is going to go—which is really common—because it’s possible they’ve been going to synagogue their whole lives. It’s possible they had a bar mitzvah,” she said. “They may be as schooled in Judaism as anyone else there, so telling them how things go can be extremely condescending.” (See sidebar on page 50 for more tips from Headlee.)

Samira K. Mehta’s The Racism of People Who Love You: Essays on Mixed Race Belonging (Beacon Press) touches on similar issues. However, Mehta’s book is less of a how-to than a collection of meditative essays that range from the personal to the political. By book’s end, we have gotten to know her—and trust her insights. The author of a previous book, Beyond Chrismukkah: The Christian-Jewish Interfaith Family in the United States, Mehta also heads the “Jews of Color: Histories and Futures” project, an initiative that studies the experiences of Jews of color in the United States, at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she teaches.

In one of the book’s most engaging essays, “Where Are You Really From?: A Triptych,” she helps readers understand her frustration when people she has newly met ask her, a bit too insistently, just that question. The reason, she explains in the book, is because even after she answers, truthfully, that she was raised outside of New Haven, Conn., too often the follow-up question is, “But where are you really from?”

To Mehta, a Jew by choice who is the daughter of a white Protestant mother from the Midwest and

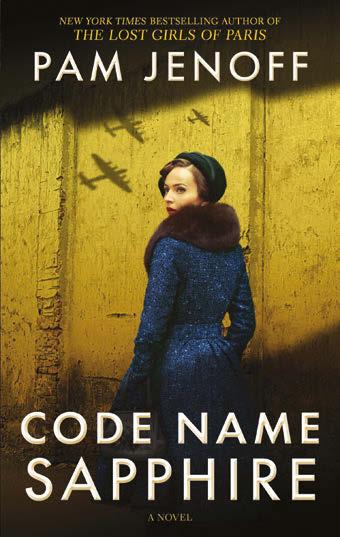

ONE BOOK, ONE HADASSAH

Join us on Thursday, April 20 at 7 PM ET as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein interviews best-selling author Pam Jenoff about her latest historical fiction book, Code Name Sapphire . Set during World War II and centered around three compelling women, the novel is inspired by true stories of resistance during World War II. The page-turner, filled with complex family relationships, secrets and betrayals, explores the sacrifices and bravery of women during perilous times. an immigrant father from India, the query can sound nosy or, worse, insulting. Is the person she has just met insinuating that she does not really belong—that she is not really Jewish, or really white or really South Asian?

This event is free and open to all. To register, go to hadassahmagazine.org .

In a Zoom interview, Mehta added that slights like these may be thoughtlessly unintentional, but they sting nonetheless for their suggestion that she is an outsider. But you can— and should—try to mend the hurt by talking about it, she said.

“If your intent was not to make me feel bad, but just curiosity, then you must actively listen when I tell you how your comments made me feel,” Mehta said.

In her book, Mehta does not directly write about her conversion to Judaism. Rather, the meaning and joy she finds in Jewish tradition, ritual and culture—matzah ball soup is her go-to comfort food—are made clear throughout. And she, too, brings up questions and problems that have arisen during Jewish religious services.

“At the synagogue, treat me like I am a member, a friend of a member or a prospective member,” she said in the Zoom call. During kiddush lunch, for instance, she suggests such conversation openers as asking about a favorite bagel place or the rabbi’s sermon.

The most difficult conversations, Mehta writes, are those with people (as her title suggests) whom she reciprocally loves and cares about—but who also have blind spots about some of their own biases. She acknowledges that such conversation can be challenging, regardless of an individual’s background.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS FOR PESACH

Among the many tunes that bring us to a Passover state of mind—from “ Dayenu ” to the ditty about that one young goat— Debbie Friedman’s “Miriam’s Song” stands out. A catchy folk anthem that describes Miriam leading the women’s-only dance and singalong after the parting of the Red Sea, the song inspired generations of campers to sing about the Exodus.

The famed singer-songwriter’s joyous reimagining of Jewish texts befits every seder. And that is why two picture books about Friedman’s life and music top this selection of new children’s reads for the holiday, a list that reverberates with joy, magic and whimsy.

Both Debbie’s Song: The Debbie Friedman Story by Ellen Leventhal, illustrated by Natalia

In Jewish communities, however, the fact that we all feel vulnerable to antisemitism can make these talks particularly difficult. “Because Jews experience antisemitism, they can feel that they can’t possibly be doing anything or saying anything that is racist or can be misunderstood that way,” she said. “If you believe in tikkun olam, having someone say you said or did something racist can strike at your sense of self, at your core sense of being a good Jew.”

Rather than walk away hurt, talk through the issues, Mehta encouraged. “I’ve been in conversations where, after a discussion of a misunderstanding, I’ll say, ‘You know, I may have been overly sensitive, I was wrong to call you out.’ And that is fine,” she said, “because you will have a better understanding of each other and cleared the air.”

That hope for better understanding of the experiences and history of our increasingly multicultural Jewish community is the thread that ties together this selection of books. They become a way to investigate assumptions and stereotypes about who and what Jews are and look like.

Mehta suggests in her book to “take it upon yourself to become more open.” Reading about the struggles of women of color with Jewish heritage may help all of us open up and welcome each other into a common fold.

Diane Cole is the author of a memoir, After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges, and writes for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and other publications.

Meanwhile, holiday preparations take over a pirate’s ship in Pirate Passover by Judy Press, illustrated by Amanda Gulliver (Kar-Ben). In lilting rhymes, the diverse crew led by red-haired Captain Drew cleans and preps for seder night only to have a storm disrupt their plans. Chaos erupts, complete with “matzah balls rolling along the ship’s plank” and sinking into the ocean depths.

Grebtsova (Kar-Ben), and A Place to Belong: Debbie Friedman Sings Her Way Home by Deborah Lakritz, illustrated by Julia Castaño (Apples & Honey), focus on how Friedman, who passed away in 2011, brought foot-stomping joy and a passion for music into Jewish liturgy and texts. Debbie’s Song includes her time on a kibbutz in Israel and a helpful Hebrew glossary.

Joyful reinvention and silliness infuse books that showcase Passover on the high seas. In

Under-the-Sea Seder , written and illustrated by Ann D. Koffsky (Apples & Honey), Miri’s mother and father attempt to stop her boisterous activity during the seder in scenes likely familiar to many parents. Miri and her cat then slip beneath the table into an imaginary “seder submarine,” which carries them to a Passover celebration with colorful sea creatures. How is this night different from other nights? Because on this night, Miri says, “there are three sea monsters.”

Afikomen by Tziporah Cohen, illustrated by Yaara Eshet (Groundwood Books), is another magical adventure that starts under the seder table, where three siblings, looking to hide the afikomen, are brought back in time to ancient Egypt to help a young Miriam hide baby Moses on the Nile. Beautifully illustrated, the wordless picture book will allow children to weave their own voices and interpretations into the story as it develops from page to page.

—Leah Finkelshteyn

Fiction

Code Name Sapphire

By Pam Jenoff (Park Row)

It should come as no surprise that Pam Jenoff has produced another pageturner with her newest novel, Code Name Sapphire Weaving together littleknown stories of resistance during the Holocaust, the historical thriller illuminates the role of women in a secret network that rescued downed Allied airmen during World War II.

Jenoff, whose previous best sellers include The Lost Girls of Paris and The Woman With the Blue Star, is well-qualified to explore these events. She has a master’s in history as well as a law degree and has worked at the Pentagon and at the United States Consulate in Krakow, Poland, focusing on, among other issues, the restitution of property taken by the Nazis.

Code Name Sapphire introduces us to a trio of compelling women: German cartoonist and satirist Hannah Martel, whose tragic backstory includes a narrow escape from Nazi Germany; her wealthy cousin Lily Abel, who hides Hannah in her home in Nazi-occupied Brussels; and strong-willed, secretive Miche- line, who, with her brother, Matteo, runs the Sapphire Line, a dangerous underground resistance network.

The fast-paced story alternates between the viewpoint of the three women, each trying to survive under an increasingly restrictive occupation. Desperate to leave Nazi territory for safety in the United States, Hannah is forced to help Micheline smuggle Allied pilots to safety through Brussels, Holland and France.

Lily, however, is determined to keep to her daily routines: “Stay silent, Lily thought…that was the lesson of the war and the only way to survive it.” She pretends that life will continue much as it had before the occupation, even as her husband, Nik, is deprived of his medical practice because he is Jewish.

Nevertheless, Hannah and Micheline’s clandestine activities draw Lily and her family into danger—and a heart-pounding conclusion—as the women must choose between family and freedom, safety and resistance.

Set against the backdrop of love, lost and found; complicated family relationships; and secrets and betrayals, Code Name Sapphire most of all explores the bravery of women under siege. As Hannah acknowledges to herself, “No one bestowed courage or freedom or self-determination—one simply decided to take it.”

An author’s note describes the true stories that inspired the novel, from an attempt to liberate prisoners on a train to Auschwitz by three men from the Jewish Defense Committee to the work of the Comet Line, a Belgian network that used 3,000 civilians to help 775 Allied airmen escape occupied Europe.

Through her new novel, Jenoff writes, she is highlighting the unsung heroines of the resistance movements, as “so many stories of women have been lost to a history that ignored them.”

Around 70 percent of the operatives in the Comet Line were women; not all of them survived the war. Code Name Sapphire is a testament to their bravery.

—Stewart Kampel

Stewart Kampel was a longtime editor at The New York Times

Kantika

By Elizabeth Graver (Metropolitan Books)

Elizabeth Graver’s newest novel is a sprawling saga of a Sephardi Jewish family centered around one strongwilled woman, Rebecca Cohen. A

ON YOUR SHELF: NEW BOOKS FOR EARLY SPRING

By Sandee Brawarsky

Künstlers in Paradise

by Cathleen Schine (Henry Holt)

Over many best-selling novels, Schine has demonstrated her talent for creating unforgettable characters using empathy and humor. Here, a trio spends the early months of the pandemic locked down together: 93year-old Salomea, known as Mamie; her housekeeper/friend; and her 20-something grandson from New York City. Mamie is teaching her grandson “the ways of the world. A vanished world, but so be it” as she recounts for him family stories of Vienna—her family left in 1939—and their new lives in Los Angeles among a community of artists.

Take What You Need

by Idra Novey (Viking)

Novey is a poet and the author of two previous novels; her first, Ways to Disappear , won the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature in 2017. She has described herself as an Appalachian Jew, and this novel is set in the Allegheny Mountains where she grew up. The narrative unfolds through the alternating voices of two women—Leah, who fled her hometown, and Jean, her estranged stepmother. Upon Jean’s death, Leah returns and learns that her stepmother had become a sculptor, welding towers of metal from found materials. In vibrant yet spare prose, Novey tells a story of finding beauty in what had been cast aside.

The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions by Jonathan Rosen (Penguin) Rosen’s childhood best friend and Yale classmate, Michael Laudor, grew up in a liberal, Jewish home in New Rochelle, N.Y. Laudor was known to be brilliant. Twenty-five years ago, however, he killed his pregnant girlfriend, a tragedy that still reverberates for Rosen. An accomplished author, Rosen writes of their parallel coming of age and rigorously researches the web of Laudor’s life. This is an important work about schizophrenia and mental health policy—and about helping people who need help.

The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent Listening by Ari Shapiro (HarperOne)

Shapiro, a host of NPR’s All Things Consid‑ ered , begins his memoir-in-essays by recalling that he became a public speaker in first grade in Fargo, N.D., when he was charged, as one of few Jews, to explain Hanukkah to his school. That, and his later experience as an openly gay teen in Portland, Ore., sparked his passion for listening and making connections. A man of wide curiosity, he recounts the stories behind some of the stories he has reported, understanding that one of the best ways for a journalist to tell a big story is through a small one.

Unearthed: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book, and a Search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust by Meryl Frank (Hachette) work of historical fiction, Graver explains in an author’s note that the story is loosely based on her maternal grandmother of the same name. Indeed, the author uses real names and actual family photographs throughout the book, even as she takes liberties with facts and fictionalizes personal experiences. The result is a story of immigration, tenacity, family bonds and change that sits in a sort of liminal space between fact and fiction, making for fascinating reading.

Frank, who was appointed by President Barack Obama to be ambassador to the United Nation Commission on the Status of Women, is not the child or grandchild of survivors. However, she grew up preoccupied with the past—with what had happened to her extended family before, during and after the Shoah. Through extensive research, she tracks down her family’s history, in particular the tragic story of a cousin who was a leading figure in Vilna’s Yiddish theater.

Sandee Brawarsky is a longtime columnist in the Jewish book world as well as an award-winning journalist, editor and author of several books, most recently 212 Views of Central Park: Experiencing New York City’s Jewel From Every Angle.

CHARITABLE SOLICITATION DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC.

40 Wall Street, 8th Floor – New York, NY 10005 – Telephone: (212) 355-7900

Contributions will be used for the support of Hadassah’s charitable projects and programs in the U.S. and/ or Israel including: medical relief, education and research; education and advocacy programs on issues of concern to women and that of the family; and support of programs for Jewish youth. Financial and other information about Hadassah may be obtained, without cost, by writing the Finance Department at Hadassah’s principal place of business at the address indicated above, or by calling the phone number indicated above. In addition, residents of the following states may obtain financial and/or licensing information from their states, as indicated. DC: The Certificate of Registration Number of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. is #40003848, which is valid for the period 9/1/2021-8/31/2023. Registration does not imply endorsement of the solicitation by the District of Columbia, or by any officer or employee of the District. FL: A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC. (#CH-1298) AND HADASSAH MEDICAL RELIEF ASSOCIATION, INC. (#CH-4603) MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE 1-800-HELP-FLA, OR ONLINE AT www.FloridaConsumerHelp.com. KS: The official registration and annual financial report of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. is filed with the Kansas Secretary of State. Kansas Registration #237-478-3. MD: A copy of the current financial statement of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. is available by writing 40 Wall Street, 8th Floor, New York, New York 10005, Att: Finance Dept., or by calling (212) 355-7900. Documents and information submitted under the Maryland Charitable Solicitations Act are also available for the cost of postage and copies, from the Maryland Secretary of State, State House, Annapolis, MD 21401 (410) 974-5534 MI: Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. MICS #13005/Hadassah Medical Relief Association, Inc. MICS # 11986/ The Hadassah Foundation, Inc. MICS #22965. MS: The official registration and financial information of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. may be obtained from the Mississippi Secretary of State’s office by calling 1(888) 236-6167. NJ: INFORMATION FILED BY HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC. AND HADASSAH MEDICAL RELIEF ASSOCIATION, INC. WITH THE NEW JERSEY ATTORNEY GENERAL CONCERNING THIS CHARITABLE SOLICITATION AND THE PERCENTAGE OF CONTRIBUTIONS RECEIVED BY THE CHARITY DURING THE LAST REPORTING PERIOD THAT WERE DEDICATED TO THE CHARITABLE PURPOSE MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY BY CALLING (973) 504-6215 AND IS AVAILABLE ON THE INTERNET AT www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/charity/chardir.htm. NC: FINANCIAL INFORMATION ABOUT HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC. AND A COPY OF ITS LICENSE ARE AVAILABLE FROM THE STATE SOLICITATION LICENSING BRANCH AT 919-8145400 OR FOR NORTH CAROLINA RESIDENTS AT 1-888-830-4989. PA: The official registration and financial information of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc., Hadassah Medical Relief Association, Inc., and The Hadassah Foundation, Inc. may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling toll free, within Pennsylvania, 1(800) 732-0999. VA: A financial statement of the organization is available from the State Division of Consumer Affairs in the Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA 23218, Phone #1 (804) 786-1343, upon request. WA: Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc., Hadassah Medical Relief Association, Inc. and The Hadassah Foundation, Inc. are registered with the Washington Secretary of State. Financial disclosure information is available from the Secretary of State by calling 800-332-GIVE (800-332-4483) or visiting www.sos.wa.gov/charities. WV: West Virginia residents may obtain a summary of the registration and financial documents of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. from the Secretary of State, State Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305. WI: A financial statement of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. disclosing assets, liabilities, fund balances, revenue, and expenses for the preceding fiscal year will be provided to any person upon request. ALL STATES: A copy of Hadassah’s latest Financial Report is available by writing to the Hadassah Finance Dept., 40 Wall Street, 8th Floor, New York, New York 10005. REGISTRATION DOES NOT CONSTITUTE OR IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, SANCTION OR RECOMMENDATION BY ANY STATE. Charitable deductions are allowed to the extent provided by law. Hadassah shall have full dominion, control and discretion over all gifts (and shall be under no legal obligation to transfer any portion of a gift to or for the use or benefit of any other entity or organization). All decisions regarding the use of funds for any purpose, or the transfer of funds to or for the benefit of any other entity or organization, shall be subject to the approval of the Board or other governing body of Hadassah. The Hadassah Foundation, Inc. is a supporting organization of Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc. September 2022

The lyrical novel, whose title is the Ladino word for “song,” opens in 1907 in Constantinople. By 1925, the Cohen family has moved to Barcelona, having lost their money and social status in the Ottoman capital during World War I. Rebecca chafes against the cloistered role expected of a young Jewish woman in Spain. Tenacious in her desire to help her impoverished family, she pursues work as a dressmaker and sets up a successful shop, though she must hide her Jewishness. By the time she is 24, she is married and has two sons— discovering the joys of motherhood even as her marriage fails: “Her old determination has been strengthened to almost bullish proportions by the birth of her children and the pathetic behavior of their so-called father,” Graver writes.

Kantika takes readers from Spain to Havana and then to America, with an arranged second marriage along the way. Rebecca’s determination to ensure her family’s survival steers her through loss, displacement and the all-too-common antisemitism of the era. Indeed, Rebecca’s focus on survival is at the core of the book. Through hardships, through times of plenty, she “does” for her family. And that includes her stepdaughter, Luna, a young woman with a disability. Their well-drawn relationship is the most compelling in the book, and Rebecca’s advocacy helps Luna come into her own.

While most of the book is richly detailed and impeccably plotted, the final section feels condensed and rushed, just as Rebecca finally gains a measure of happiness. Whether this is intentional or not is unclear, but it does make for an abrupt ending for a character who deserves better.

Contemporary Jewish fiction and immigrant sagas are for the most part overwhelmingly Ashkenazi, so this Sephardi story from a Sephardi author, threaded throughout with Ladino phrases and distinct cultural touchstones, is welcome.

—Jaime Herndon

Jaime Herndon is a writer and avid reader. Her work can be found on Book Riot, Undark, Kveller, Motherly and other places.

Frankly Feminist: Short Stories by Jewish Women from Lilith Magazine

Edited by Susan Weidman Schneider and Yona Zeldis McDonough (Brandeis University Press)

Like the brides in a Chagall painting, the images described in Lilith magazine’s collection of short stories float above the earth, surreal visuals that are nevertheless tethered to reality. There is the mikveh in the California woods where Orthodox women cleanse themselves of their secrets and pray for their fervent desires; a white satin chuppah under which a bride dreams of another (non-Jewish) man; the eggplants, potatoes, tomatoes and peppers that an Ethiopian immigrant to Israel cooks into a savory stew to make her new country feel like home.

Together, the stories create a powerful portrait of Jewish women’s experiences. They span a broad multicultural, cross-denominational and feminist scope as they explore relationships in which readers will encounter the “comfortably familiar and dangerously illicit,” the editors note in the prelude.

PERPETUAL YAHRZEIT

Kaddish will be recited annually for your loved one in perpetuity in the Fannie and Maxwell Abbell Synagogue at Hadassah Medical Center beneath Marc Chagall’s iconic stained glass windows.

ENHANCED PERPETUAL YAHRZEIT

Kaddish will be recited for your loved one daily for 11 months after burial, after which Kaddish will be recited annually.

ADVANCE YAHRZEIT

A reservation to ensure Kaddish will be recited for you and your loved ones upon their death. Available in standard and Enhanced Perpetual Yahrzeit.

The 44 stories in the collection were selected from 200 originally published in the feminist Jewish magazine since its founding in 1976. Divided into six sections—Transi- tions, Intimacies, Transgressions, War, Body and Soul, To Belong—the stories teem with women’s insights on life, from conception to Kaddish.

Yiddish author Esther Singer

Kreitman— Isaac Bashevis Singer’s sister— writes from the perspective of a newborn in “The New World,” translated from the Yiddish by Barbara Harshaw. The baby hears her mama say, “Of course I would’ve been happier if it had been a boy.”

“I listen to all of this,” the baby thinks, “and it is very sad for me to be alive. How come I was born if all the joy wasn’t because of me!” In her real life, Kreitman’s mother destroyed all her early writings for fear that they would make her unmarriageable.

In many of the stories, characters use their voices to demonstrate their independence as risk-takers and rule-breakers. The seemingly mundane activity of two Orthodox teens putting on makeup is tinged with sexual taboo in Elena Sigman’s “Face Me.” In “Flight,” Phyllis Carol Agins traces 80-year-old Hanina’s journey backward from the present—living with her son in Philadelphia—to her escape from her policeman husband’s restrictions in France when she was 37 then to her time spent wandering the Arab market and baking bread with her mother in Algeria at age 13.

These are stories that will stay with readers. They are alternately fraught with emotion and lightly lined with humor and tenderness; stained with antisemitism and filled with the ultimate human desire to belong.

—Rahel Musleah

We provide vans for underprivileged special needs children , seniors , and those with debilitating illnesses .

This is indeed a “life-changer”, enabling a hassle-free way to doctor and therapy appointments, attending family events, socializing with friends... for many who live every day with loneliness.

$45,000 - used wheelchair van

$20,000- adapt a minivan

$5,000 - refurbish a donated van (contact us for naming opportunities)