4 minute read

Theory of Hospitality

Something that has both historically and presently sets women’s rhetoric apart from men’s is hospitality. While men may engage in hospitality rhetorics, women have had to find alternative routes for building their ethos for their audience than men do. What we’ve seen in the canon of women’s rhetoric is that women speak from a place of liminality. Their exclusion from education, the academy, and writing spaces at large means that women walk a trepidatious tightrope of performativity, persuasion, and self-representation that has heavier consequences and more severe risks than men do when speaking.

But women are smart. Throughout time, they’ve found innovative ways to walk the tightrope of liminality and be successful. These women created a new ethos by providing a different means of persuasion through contexts that were unique to women. This includes the places that made up their daily lives which were different than that of a man’s, i.e. the kitchen, parlor, nursery, garden, and their own bodies. Women also found ways to be persuasive without words that made sense with their unique ethos: hospitality.

Advertisement

As Sean Barnette describes in his essay “Dorothy Day’s Voluntary Poverty,” hospitality rhetoric means “An ecology of objects and practices involved in offering guests space, shelter, food, and other materials. These objects and practices allow hospitality to do rhetorical work” (112). Women’s hospitality, then, affects people physically as well as intellectually. Through the lens of Kenneth Burke’s definition of Identification, or constructing similarities in a group of participants to build ethos, we can see how women’s hospitality rhetoric is unique to them. By using materials and spaces to create a

sense of similarity between speaker and audience, women are able to give their audience a sense of togetherness and understanding, allowing them to persuade others by changing the identity of the speaker to someone that belongs not on the outside of the conversation but inside a community of people with a similar ethos.

In this cookbook, I’ll be focusing on food as an act of hospitality rhetoric. Women unsurprisingly talk about food a lot-- our hands and bodies being the source of food and the creator of food that perpetuates life-- and commonly find it as a source of inspiration. Women feeding others and doing it well fits with their ethos; we’re commonly measured as mothers, wives, and daughters by our ability to cook. I have yet to encounter someone who doesn’t have memories of their mother cooking that they consider significant: what your mom makes on a rainy day, what she makes on your birthday, when and if she fails at cooking-- it’s all meaningful.

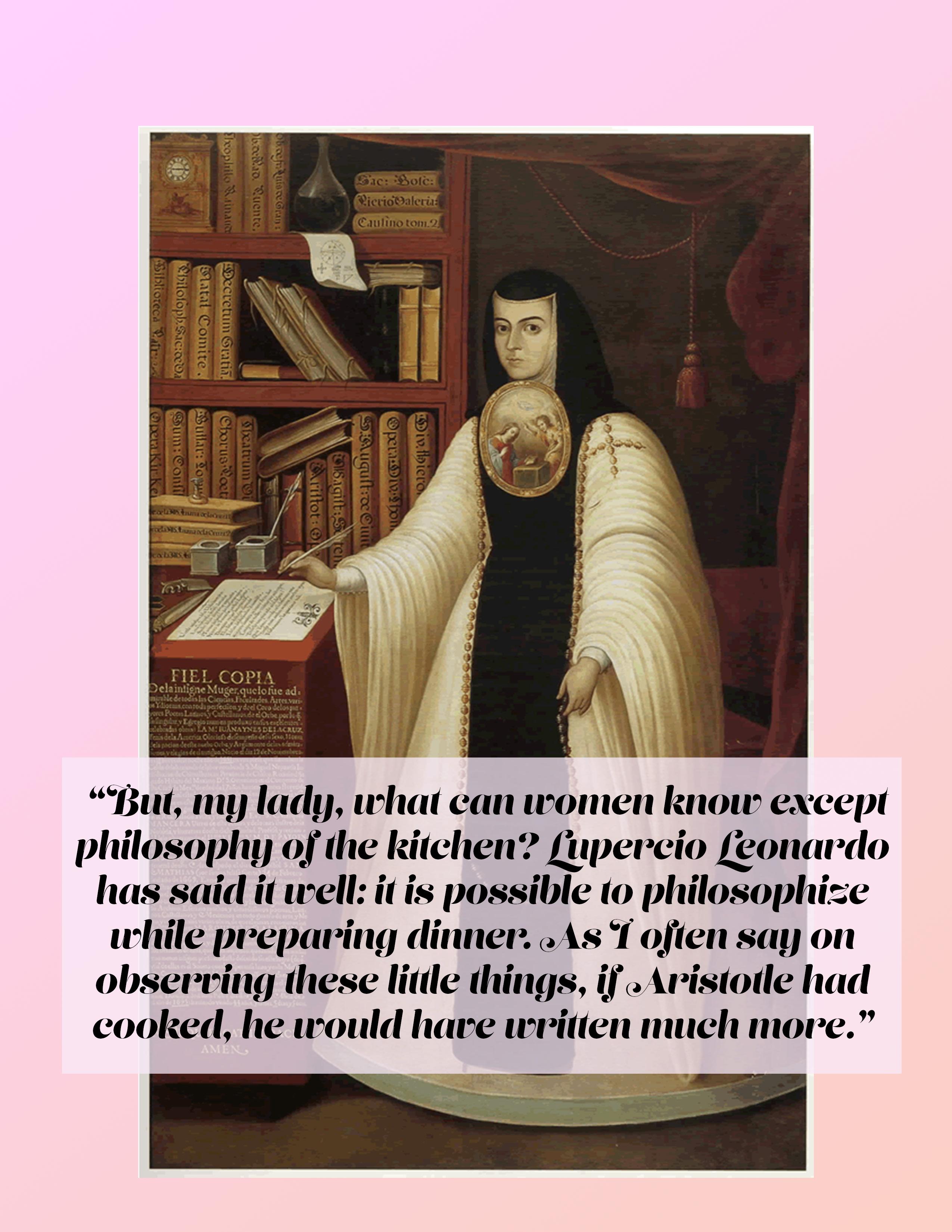

I’ll be focusing on Margery Kempe, Sor Juana de la Cruz, and Virginia Woolf because they all speak about food in a variety of ways. Margery Kempe talks about food as an act of radical love. Sor Juana talks about food philosophically. Virginia Woolf talks about food to demonstrate the disproportional privilege between men and women. Food in all of their circumstances reflects on their ethos as women and shows us exactly what food can mean.

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz

Ale’s mother sent this recipe to her over Facebook messenger, as she does most recipes. These recipes are important to her-- this one specifically was sent as an attempt to get a piece of her home and culture when she was living in east Texas. Mom’s exact recipe is: “Quema los chiles para que se inflen y les quitas el cuernito, luego los abres de un lado y le sacas las senillas y los rellenas de lo que quieras si los vas a meter al horno asi los dejas y si los vas a lamprear los revuelcas en harina, ya rellenos los chiles en una vasija onda pones las claras de huevo y las bates hasta que quede firme las claras, luego le pones poquito harina espolvoreada y las yemas y lo bates otra ves. pasa los chiles por el huevo y lo cubres bien, en un sarten con aceite caliente los lampreys y ya que se haga bien cocido el huevo los sacas y escurres.”

Ingredients:

For Chile Rellenos:

6 Fresh Pasilla Chiles 3 eggs, seperated ¼ cup of all-purpose flour 1 8 oz. package of Oaxaca cheese or other filling ¼ tsp. Of salt ½ cup of canola oil (or other oil of your choice) for frying

For Salsa:

4 tomatoes Half a white onion A jalapeno or serrano pepper A clove of garlic ½ tsp. Of salt ¼ tsp Cumin 2 tbsp. Of olive oil Juice of ½ a lime

For Optional Filling:

½ lb. of ground beef or tofu ½ yellow onion, diced 1 clove of garlic, minced 1 jalapeno, diced ½ bell pepper, diced 1 beefsteak tomato, diced ½ potato, diced ½ tsp. Salt ½ tsp. Pepper ¼ tsp. Cumin 1 tbsp. Olive oil