BELLE EPOQUE CAIRO

Retrieving and revitalizing the city historical center.

Università IUAV di Venezia

Final Thesis MA in Architecture

Supervised by

Retrieving and revitalizing the city historical center.

Hany Youssef 296169

Prof. Fernanda De Maio

BELLE EPOQUE CAIRO

“In Cairo, you can see the ancient and the modern in harmony and chaos.”

- Ahmed M. Badr.

Abstract

The ongoing relocation of administrative and ministry functions to the New Administrative Capital is leaving a series of late 19thcentury to mid-20th-century buildings in central Cairo vacant and awaiting conversion. Since these buildings are becoming more of gaps in the urban fabric of the area, The state is looking now to private developers ‘decade-long experience with arts-led re-developments in downtown’, and inspired by global north’s model for using the arts and culture as a tool to “revitalize” decaying downtowns with the creative scene in downtown saturated with socially and political subversive tones. Efforts by the state have been intensified to sterilize the remnants of the informality in the area through capitalized conditioning of downtown creative industries. This inspired a new discourse to uproot and localize the concept of gentrification as it is always faced by objections that it is an Anglo-American construct that doesn’t exist in the global south.

In this thesis, an attempt is made to deconstruct this multi-layered convolution of heritage, art, capital, and dissent and analyze the implication of all of that on the social and built environment. Therefore try to come up with a project proposal to ignite an effort to develop the area and retrieve its old significance, this time without marginalizing any social class and with inclusion of all the members of the conversation that should be indulged about the city’s future.

Grandiose building Downtown (fig. 1).

I. Introduction

A. Background, reserach objectives and methodology

Cairo, similar to many megacities in the Global South, is currently Backly simultaneously experiencing urban sprawl and inner-city redevelopment. The two intersecting modes of development are manifested in Meth’s speculative ultra-exclusive desert expansion and mass regeneration of long-neglected areas in its center earmarked for business and tourist redevelopment (Davison & Mourad, 2018). Both modes converge in the currently underway plans to relocate administrative and ministerial functions from central Cairo to the New Administrative Capital currently under construction some 45 kilometers east of Cairo. An array of vacant 19th and 20th-century buildings are consequently left behind in a contested city center highly attractive for lucrative redevelopment yet saturated with a recent history of revolt, social dissidence, and subversive creativity. The state’s long-established vision for a touristic and cultural city center (El-Kadi & ElKerdany, 2006), combined with the buildings’ heritage designation, makes for an unusual example of a large-scale state-led renovation that hardly entails destruction and reconstruction. Driven by the expertise of niche private real estate developers gained over the preceding ten years, the state took the lead in investing heavily in Downtown real estate and actively pursued adaptive reuse as a way to optimize profits.

However, its job was only restricted to clearing the way for private reconstruction via the “restoration of order” through beautifying projects, the removal of all evidence of informality and dissent, and the dwindling of subversive creative industries. The marriage of private development with the state-familiar phenomenon common in cities in the Global South has come to a close, opening up discussion about the consequences. implications of adaptive reuse and the relation between capital, heritage, and state.

Downtown Cairo has seen substantial changes as a result of the city’s expansion and development, nevertheless, notably the transfer of administrative duties to the new administrative capital. Due to this, downtown Cairo now features several deserted buildings and plots that offer potential for urban rehabilitation and revitalization. The concept of adaptive reuse is becoming a more popular strategy used by planners, architects, and legislators to revitalize abandoned areas while protecting their cultural legacy.

Adapting these abandoned sites for new purposes and services, such as mixed-use complexes, cultural institutions, and public amenities need a very careful approach which opens the discussion about how the area’s 19th and 20th century architecture should be approached. The latter is discussed concerning the imperialist overtones of maintaining “Belle Epoque Cairo.” While the exact plans for these vacated buildings started to appear as touristic and commercial redevelopment, we need to take a step back and analyze if these plans will really help revitalize the city center. Suggestion of an adaptive reuse of one of these vacant plots in downtown Cairo is examined in this thesis, along with how it might support the social, cultural, and economic life of the city. Through the analysis of case studies, theoretical frameworks, and practical design interventions.

Some particularly relevant locations for this thesis, such as abandoned structures and administrative buildings, were inaccessible due to securitization and the usual challenges associated with obtaining licenses. The majority of the data is based on articles and reports from news agencies, which may not be sufficient or correct, due to the difficulties in obtaining or lack of reliable information regarding land use, ownership, and heritage listings from local government entities.

B. Limitations

II. THE RESEARCH

Adaptive reuse, gentrification, socioeconomic and political narratives.

A. “Belle Epoque Cairo” Trial of untangling Cairo Downtown character.

Following the significant degradation brought on by the 1992 earthquake, there was a greater desire to preserve the 19th and 20th century architecture that had begun to appear in the 1980s and was centered in the city center, particularly Downtown. A loose coalition of an Egyptian cultural elite, conservators, and state actors have attempted to revisit what has been named Cairo’s Belle Époque, aiming to rewrite the accepted narrative that shrouded it in colonial imperialism and labeled it un-Egyptian in contrast to Egypt’s proud ancient Egyptian, Coptic, and Islamic heritages (El Kadi & Elkerdany, 2006).

The term Cairo’s Belle Époque was essentially coined by Trevor Mostyn through the publication of Egypt’s Belle Époque: Cairo 1869-1952 in 1989. While it was not received well by Western academics who negatively described the publication and the term as Imperial nostalgia, it was embraced by Egypt’s cultural elite. This cohort, disturbed by the pervasive negligence and destruction of “Cairo’s glory years” (see Raafat, 2003), have resorted to the romanticization of the period between 1870 and 1952 by attempting to rebrand it as a cultural and architectural renaissance. This narrative that has now become mainstream nostalgically depicts Belle-Époque Cairo as a mythic cosmopolitan global capital that has fallen victim to cultural decline and political corrup-tion (El Kadi & Elkerdany, 2006). All historical references to social inequity, cultural and colonial imperialism, and Cairo’s cosmopolitan core are disregarded.

Just a little over 50 years earlier, the narrative was one of proud cultural and social reclamation of Cairo’s previously exclusive colonial capital (Abu-Lughod, 1971). The romanticizing stance taken by these cultural elites has been met with much scrutiny for its elitist tones and selective forgetfulness of the negative

implications of monarchical colonialism. A more critical group of architectural historians, urbanists, and conservators within this cohort take on a less nostalgic tone to challenge the dismissal of Cairo’s Belle Époque as an imported copy of European modernity Instead, it accuses this stance of complicity in the subliminal equation of Europeanization and modernization. It rejects its acceptance of the orientalist narrative that, on the one hand, confines “Egyptian” heritage within the stereotypical categories of ancient Egypt and Islamic Cairo with all of their historical imperialistic connotations of stagnation and exoticness, and, on the other hand, labels modern Downtown as “unEgyptian” European, and colonial (Volait, 2013; Cairobserver, 2011). Instead, this group argues that the heritagisation of Cairo’s Belle Époque represents a subversive, homegrown view on Egyptian heritage; challenging the boundaries set according to a cultural hegemony manufactured by colonial tastes. In a post-colonial setting, architecture built in colonial times cannot be simplistically labeled as colonial. An analysis of its complex evolution that considers the “dynamics of exchange, circularity and choice” must be made (Naguib, 2008, as cited in Volait, 2013). Commissioners, owners, funding sources, local actors, and occupants must be traced before making claims about Downtown being a typical colonial urban development project (Cairobserver, 2011). In this sense, reclaiming Cairo’s Belle Epoque is seen as a reclamation of heritage-making itself (Volait, 2013).

However, Choosing this labeling for the downtown area of Cairo here does not represent a subversive view of the Egyptian heritage. On the contrary, it is a way to look at the area from the perspective of its original initiation, to accept reality and try to get the best out of it. The first residents of Downtown were a mixture of a growing foreign community and a small percentage of wealthy “Francophile” Egyptians (Abu-Lughod, 1971) While the bulk of native Egyptian Cairene residents resided in the new quarters as a service population or in the ancient quarters, which were divided into numerous historic villages on either bank of the Nile The British occupation in 1881, which resulted in the building of the Kasr el-Nil barracks on the eastern bank of the Nile (now the site of Nile Cornice Drive and the Nile Ritz Carlton overlooking Tahrir Square), worsened this composition’s divisions. Though Downtown and its surrounding regions suffered significant changes after the socialist Arab Nationalist regime took power in 1952 and the 1956 migration of foreigners, which brought with it

a new oligarchy of army officers and statesmen and a burgeoning middle class. The wealthiest and most westernized citizens of Cairo lived there, and it continued to serve as the city’s façade.

Gharib Morcos Building 1920 (fig. 3).

Detail of Gharib Morcos Building 1920 (fig. 2).

Egypt’s decision to recognize “Belle Époque” architecture as national heritage marks an interesting turning point in the nation’s nuanced history, which is layered on top of Egypt’s ancient, medieval, modern, and current pasts. The term is a reference to the Khedivial and monarchical era that spanned from the 1850s to the 1950s, and it represents a civilization that has long been mocked by the intellectual elite. However, as numerous studies and projects have shown, “Belle Époque” architecture has never been more prevalent in Egypt than it has been in the first ten years of the twenty-first century. It is a sort of “invented tradition”1 in its own right, and as such, it provides an excellent field of study for seeing how new elements are incorporated into the range of Egyptian cultural legacy from an anthropological perspective. It is made even more notable by the fact that it touches on items that are initially thought to be “dissonant”2 since, to a postcolonial observer familiar with the historical background, these artifacts naturally evoke thoughts of colonial architecture and the legacy of colonization.

The neglect of Belle Époque architecture in Cairo’s urban redevelopment reflects a complex interplay of modernization priorities, economic pressures, legal inadequacies, and socio-political challenges. To bridge this gap, there needs to be a concerted effort to raise awareness about the historical and cultural value of this period, strengthen legal protections, and allocate resources for the preservation of this integral part of Cairo’s architectural heritage. By doing so, the city can ensure that its rich and diverse history is preserved for future generations while still pursuing modern development goals.

Modern Cairo Islamic Cairo

Pharaonic Cairo

Belle Epoque Cairo 1869-1952

B. Cairo’s adaptive reuse: Implications of shifting political and socioeconomic narratives.

The idea of adaptive reuse is not new to the Cairene landscape; in fact, has played a significant role in its development since the 11th century. But what sets apart the current trajectory from past experiences is its fundamental goal of safeguarding Cairo’s Belle Époque architecture; its paradoxical growth in conjunction with irresponsible desert development (which has historically meant abandoning the city center); its synchronization with the completely different approaches used in other inner cities redevelopment projects, like Maspero and El Werraq, which involve complete demolition and new construction; and its fraternal relationship with redevelopment led by the arts and culture and monopolized by private developers.

This sector is about the effect of socioeconomic and political narratives on the adaptive reuse process through an overview of historical cases of reuse in Cairo. As Scott states in On Altering Architecture, “Such a brood of changes [of use of buildings] is the manifestation of socioeconomic changes in the wider society.. buildings change as cities change” (Scott, 2008, p. 97).

In the aftermath of the 1952 Egyptian revolution, the first wave of state-led wholesale reuse of pre-existing buildings occurred. A nationalization drive launched by a new socialist regime in the Arab world resulted in the transformation of numerous opulent homes and palaces into state institutions and educational facilities, undermining the preexisting political and socioeconomic frameworks. Sadat’s open-door policy in the 1970s essentially welcomed capitalist development as the new norm. The advent of affluent real estate developers and their dominance of urban development signaled the state’s withdrawal from both its welfare commitments and inner city development The handing over of the historical Gezira Palace in the late 1970s

to Marriott International and the addition of two towers on its sides to maximize occupancy reflects the changing relationship between capital, heritage, and the state. of two towers on its sides to maximize occupancy reflects the changing relationship between capital, heritage, and the state.

The palace, which has a long history of usage as a hotel had been nationalized and already converted into Omar Khayyam hotel in the early 1960s under state management. Most state-led adaptive reuse endeavors had, since the 1980s, been carried out within a purely cultural and touristic framework, varying between museums and cultural venues for older heritage (i.e. Coptic and Islamic) and hotels, libraries, etc. for 19th and early 20th century buildings (El Kadi & El Kerdany, 2006). The first is mostly visible in Historic Cairo, with numerous examples of reused monuments as part of the state’s plan to transform the whole area into a “museum with no museum” (Hassan, 1999). The transformation of 16th century Mamluk houses and caravanserais into venues for folk performances and other similar activities continue today and are mostly funded by the Cultural Development Fund under the umbrella of the Ministry of Culture (MOC, n.d.). A growing group of modern art spaces in decaying Downtown began to emerge in the late 1990s and early 2000s, bringing a new kind of autonomous adaptive reuse to the Cairene landscape. Cultural spaces, temporary site specific installations, and temporary artistic activities infiltrated industrial spaces, underused hotels, and abandoned residential apartments.

Cairo Marriott Omar Khayyam Casino (fig. 4).

This section attempts to unfold the three main forms of formal adaptive reuse of Cairo’s Belle Époque before opening the discussion on current and future trajectories through the tide of arts-led redevelopment.

The Egyptian Revolution of 1952 brought the British colonialism and the monarchy to an end and with them, the aristocracy. Fundamental changes in the social fabric of the city, and especially the center where most of the monarchism took place, came almost overnight. With the gradual foreign expulsion that reached its peak in the aftermath of the nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, the once self-proclaimed cosmopolitan Cairo began a process of indigenization. This meant the disintegration of the dramatic geographical and social division between a localized Egyptian context and the rapidly emptying exclusive Westernized enclaves for Cairo’s foreign communities and Egyptian “Francophiles” (Abu-Lughod, 1971). The nationalistic, anti-colonial, Arab socialist rhetoric propagated by charismatic Nasser was accompanied by a city center undergoing rapid population succession of its previous occupants. In often a violent rejection of anything foreign-such as the Cairo Fire of 1952 preempted the revolution and saw the burning down of 42 establishments mostly linked to foreign nationals (Al-Musawwar, 1952) a gap in the Cairene social landscape was emerging. The gap left by the foreign elite would, by the 1960s, be filled in with the upwardly mobile technocrats of the new regime (Abu-Lughod, 1971).

Abu-Lughod (1971) provides a vivid account of this transformation and its effect on central Cairo’s character. Arabic replaced French on shop fronts, merchandise in shops changing to cater to a new wider clientele, foreign films replaced with Egyptian productions of the royal family and notable aristocrats that were confiscated, and ownership transferred to state bodies. Most common was in cinemas, folk performances instead of operatic ones. Despite these radical cultural changes, and contrary to popular imperial apologist assumptions, the disappearance of European influence barely affected the upscale status of what had been by then considered the upscale center of Cairo. Central Cairo is denoted by Abu-Lughod as the Gold Coast which interestingly groups Downtown together with Garden City; the first considered as Cairo’s central business district, the second its upscale residential quarter.

By 1960, many of the palaces and villas left over from the foreign exodus of 1956 were already being replaced by highrise apartment buildings to welcome the influx of a new upper class. Of the surviving ones, some were turned into embassies and consulates, and the rest showed the signs of neglect that usually preempt a land use conversion (i.e. reuse) (Abu-Lughod, 1971). Nationalization schemes saw the confiscation of palaces associated with the royal family and notable aristocratic families. According to Soheir Zaki Hawas, founder and former chair of the central department for studies, research, and policy at NOUH, and the consultant expert of the Cairo governorate for the Khedival Cairo regeneration project since 2013, historical palaces are of two types. The first includes official royal palaces that continued to be used as presidential palaces under the new republic or were turned into museums (Al-Arabiya, 2012).

A prominent example is Abdin Palace, King Faruk’s last residence, parts of which would later become offices for the revolutionary ministries of Culture and National Guidance and Land Reform, and the rest opened to the public as a museum (The New York Times, 1964). In Alexandria, Ras el-Tin palace and the Montaza grounds were opened to the public; the latter housing the Montaza Palace which turned into a hotel, rest house, and restaurant, and the newly built cabanas on the beach available for rent. The second type constitutes privately owned palaces that belonged to members of the royal family and notable aristocrats that were confiscated, and ownership transferred to state bodies. Most common was the acquisition by the Ministry of Education which oversaw the conversion of the majority of these palaces and villas into public schools; then in high demand due to Nasser’s ongoing social reform (Al-Arabiya, 2012). Lack of maintenance and unsuitable modifications and additions, exacerbated by the switch to a neoliberal system. These ancient palaces, many of which are designated as historic sites, suffered greatly under Sadat’s rule and the state’s disengagement from its social duties. Additionally, events like the earthquake of 1992 and several accounts of vandalization and looting in the aftermath of 2011 have exacerbated these effects.

C. Heritagization and management of Cairo downtown District.

Egypt’s political, economic, and cultural life has traditionally centered on downtown Cairo. Its historical significance, architectural heritage, and central location have made it a focal point for development and urban planning efforts. Unfortunately, the district has had to deal with issues including neglect, decaying infrastructure, traffic congestion, and overcrowding over the years.

The government’s recent decision to relocate administrative buildings to the New Administrative Capital is aimed at reducing congestion in Downtown Cairo and creating a modern administrative hub. This opens the chances for the district to get more attention. However, concerns have been raised about the implications of this attention for Downtown Cairo’s residents, businesses, and cultural heritage.

Under the proposed reconstruction, a mixed-use district with retail, commercial, residential, and cultural services would be present. There would be a need to construct high-rises, theaters, hotels, and shopping malls. The government actively seeks to attract companies, investors, and visitors to spur economic growth and create jobs, given the challenging economic conditions and high rates of inflation. The government accomplishes this by lowering bureaucratic delays, offering incentives for investment, and promoting travel through advertising campaigns and infrastructure improvements.

Among these incentives are tax breaks, subsidies, and investment opportunities to attract private developers and investors. To organize this the state initiated a fund called The Sovereign Fund of Egypt (TSFE), its role is to facilitate the previously mentioned incentive. The fund unveiled its ambitious plans for downtown Cairo and the Ministries Square, including the establishment of 2,600 hotel rooms, the development of 15,000 square meters of green spaces,

and the revitalization of historical buildings (Mohamed Hamouda, 2024).

Some foreign investors showed interest in having a redevelopment and operating rights for some of these buildings in exchange for a percentage of profit that goes to the government. For example in December 2021, Egypt signed a deal worth more than EGP 3.5 billion with a US consortium to upgrade the 14-storey Mugamma Al-Tahrir, also owned by TSFE (Mohamed Hamouda, 2024).

While these efforts for the redevelopment appear promising on the surface, they are primarily motivated by economic factors that put profit ahead of the needs that the community strives for, even though they may appear to be a part of the initiatives to revitalize the historic district and encourage the economy.

After the example of developing Maspero triangle, concerns arose about the potentiality for gentrification in the area. As property values rise and upscale developments take precedence, there is a risk that the district will become unaffordable for many of its current inhabitants, eroding its social fabric and sense of identity.

Some critics view the involvement of foreign investment in the development of downtown Cairo as a form of neo-colonialism They argue that allowing foreign entities to shape the urban landscape of the capital could compromise national sovereignty and cultural identity.

Gentrification is a discernible concern and makes frequent appearances in debates surrounding adaptive reuse, especially in large-scale regeneration projects. In these projects, despite economic success, advertised social mixing goals are usually not met (Bromley, Tallon & Thomas, 2005). These projects are nevertheless collectively deemed successful purely for their aesthetic delivery of the promise of “revitalization.” Understanding the surrounding context and demographics is essential to the success of any reuse project. Not every site can be transformed into a museum, hotel, or concert hall (Lens & Van Cleempoel, 2015). Kincaid (2002) simplifies stakeholders in a reuse project into investors, designers, constructors, marketeers, regulators, and users. This categorization can be criticized as being too simplistic, especially concerning “users.” It may be necessary to unbox this group and categorize it according to occupation; income level; proximity of residence to the project; etc. to ensure the needs and expectations of every user group are met. One of the main challenges with this remains to find a common vocabulary among a growing list of stakeholders.

D. Instrumentalization of arts and culture to “revitalize” decaying downtowns

One effective urban regeneration method that has arisen is the utilization of culture and the arts to revitalize decaying downtown neighborhoods. This approach leverages the transformative power of creative expression and cultural heritage to breathe new life into neglected urban spaces. Different models have been employed globally to harness the potential of arts and culture as catalysts for downtown revitalization, each emphasizing different strategies and interventions tailored to the unique context and challenges of specific urban locales.

One prominent model is the creation of cultural districts or creative clusters within downtown areas. These districts concentrate on cultural amenities, artistic institutions, and creative industries to establish vibrant hubs of cultural activity. By clustering cultural assets nearby, these districts stimulate foot traffic, attract tourists, and foster a synergistic environment conducive to artistic innovation and economic growth. Examples include New York’s SoHo district, London’s South Bank, and Barcelona’s Raval neighborhood, where the clustering of galleries, theaters, studios, and cultural institutions has played a central role in revitalizing once-decaying urban neighborhoods.

The creation of the city center’s corridors has successfully established this approach. Kodak and Philips were two of the first companies to renovate. Kodak Passage, with the theme of “The Green Oasis”, was renovated in many different aspects, including renovating the road, adding plantsand flowers, and using recyclables like plastic bottles and colored paper to decorate the streets. Following renovations, the Kodak Passageway, which connected Adly Street and Abdel Khalek Tharwat Street, was transformed into a lovely pedestrian thoroughfare, with vacant stores on either side serving as hubs for cultural and creative events. The Philips Passageway, featuring “The Light Oasis”, is an L-shaped passage connecting Sherif and Adly Streets.

Kodak Passageway before development (fig. 5).

Kodak Passageway After development (fig. 6).

The main functions of this passage are retail, food, entertainment, and other leisure services. In addition to Kodak and Philips, many abandoned or chaotic streets have been renovated with this concept into completely new passages, with roads clean and bright, and stalls in order, creating cleaner and more orderly road space for the city.

Another model involves adaptive reuse and cultural heritage preservation, whereby historic buildings, industrial sites, and vacant spaces are repurposed into arts venues, cultural centers, and creative workspaces. This approach not only conserves architectural heritage and prevents urban decay but also generates opportunities for artistic experimentation, cultural production, and community engagement.

This model could be seen with a minor and shy presence in the dilapidated and uninhabited buildings in the city center, about 30% of apartments are empty and 20% are locked, and land agents have remodeled them to build art spaces such as theatres, cinemas,galleries, and cafes to attract people. The Bab Saada Performing Arts Center, which began planning renovations in 2012, was converted from an abandoned cinema. In addition to renovating old buildings, the number of new art spaces is increasing. For example, the Cimatheque-Alternative Film Centre, dedicated to filmmakers and enthusiasts demonstrate the diversity of film development in various regions, intending to provide a venue for filmmakers and audiences to watch, discuss, learn, and create films so that more people can understand the art of film.

Even with these modest and timid attempts at adaptive reuse by state-sponsored community-driven initiatives, as well as the large, ambitious plans to capitalize on investments in mixeduse and touristic developments to capitalize on the city center, it appears that something is lacking to match the global north’s model of using the arts and culture as a tool for revitalization.

That being said, it seems to be a big initiative that affects the center on a big scale rather than a modest and small trials scattered around the area.

the CimathequeAlternative Film Centre (fig. 7).

E. The Scarcity of Libraries in Downtown Cairo: A Catalyst for Redevelopment.

The scarcity of libraries in Cairo poses a significant challenge to the city’s Cultural landscape, exacerbating existing social disparities and limiting access to essential resources for intellectual enrichment. The few existing libraries often suffer from inadequate funding, outdated facilities, and limited collections, exacerbating the challenge of promoting literacy and fostering a culture of learning within the community.

In Cairo, there are several notable libraries, though their numbers are relatively limited compared to other parts of the world for example:

1. Dar El Kutub Al-Misriyya (Egyptian National Library and Archives): Located in the heart of downtown Cairo on Al-Qasr al-Aini Street, the Egyptian National Library and Archives is one of the largest libraries in Egypt and the oldest in the country. It houses an extensive collection of books, manuscripts, periodicals, and archives, serving as a vital repository of Egypt’s cultural heritage and historical documentation.

2. The American University in Cairo (AUC) Libraries: The AUC Libraries consist of multiple branches, including the Charles A. Dana Library and Research Center and the Rare Books and Special Collections Library. While not technically in downtown Cairo, the AUC’s Tahrir Square campus is adjacent to downtown and serves as an important educational and cultural hub. The AUC Libraries provide access to a diverse range of academic resources, including books, journals, databases, and archives, supporting research and scholarship in various fields.

3. Bibliotheca Alexandria Cairo Branch: Although not as extensive as its counterpart in Alexandria, the Bibliotheca Alexandria has a branch in Cairo, located in the Zamalek district

near downtown. While smaller in scale, this branch offers a selection of books, multimedia resources, and cultural programs, providing a valuable resource for residents of downtown Cairo.

4. The French Institute of Oriental Archaeology (IFAO) Library: Situated in downtown Cairo’s historic Bab El Louk neighborhood, the IFAO Library specializes in Egyptology, archaeology, and related fields. It houses a significant collection of books, journals, and research materials, catering to scholars, students, and enthusiasts interested in Egypt’s ancient history and archaeology.

5. Goethe-Institut Cairo Library: Operated by the GoetheInstitut, this library in downtown Cairo offers a diverse selection of German-language books, periodicals, and multimedia resources, along with translations and materials related to German culture and language learning.

While these libraries represent valuable resources, it seems that they are all part of an institution rather than an institution themselves. That highlights the need for a National library that could act as an institution itself.

When it comes to the role of libraries it has long been recognized as catalysts for urban revitalization, offering more than just books – they serve as vibrant community hubs that promote education, creativity, and social cohesion. Bibliotheca Alexandria is a perfect example.

The scarcity of libraries in Cairo represents not only a challenge but also an opportunity for transformative change. By investing in libraries as catalysts for redevelopment, stakeholders can unlock the full potential of downtown Cairo as a vibrant cultural and educational hub. Through strategic initiatives to enhance library infrastructure, expand access to educational resources, and promote community engagement, downtown Cairo can reclaim its status as a thriving center of intellectual and cultural exchange, enriching the lives of residents and visitors alike for generations to come.

III. THE PROJECT

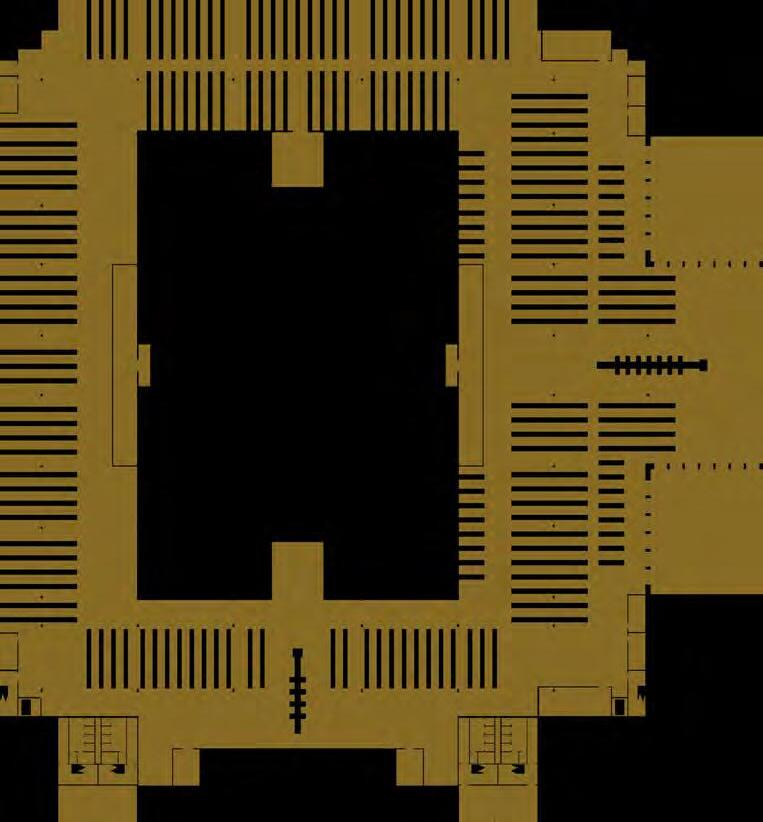

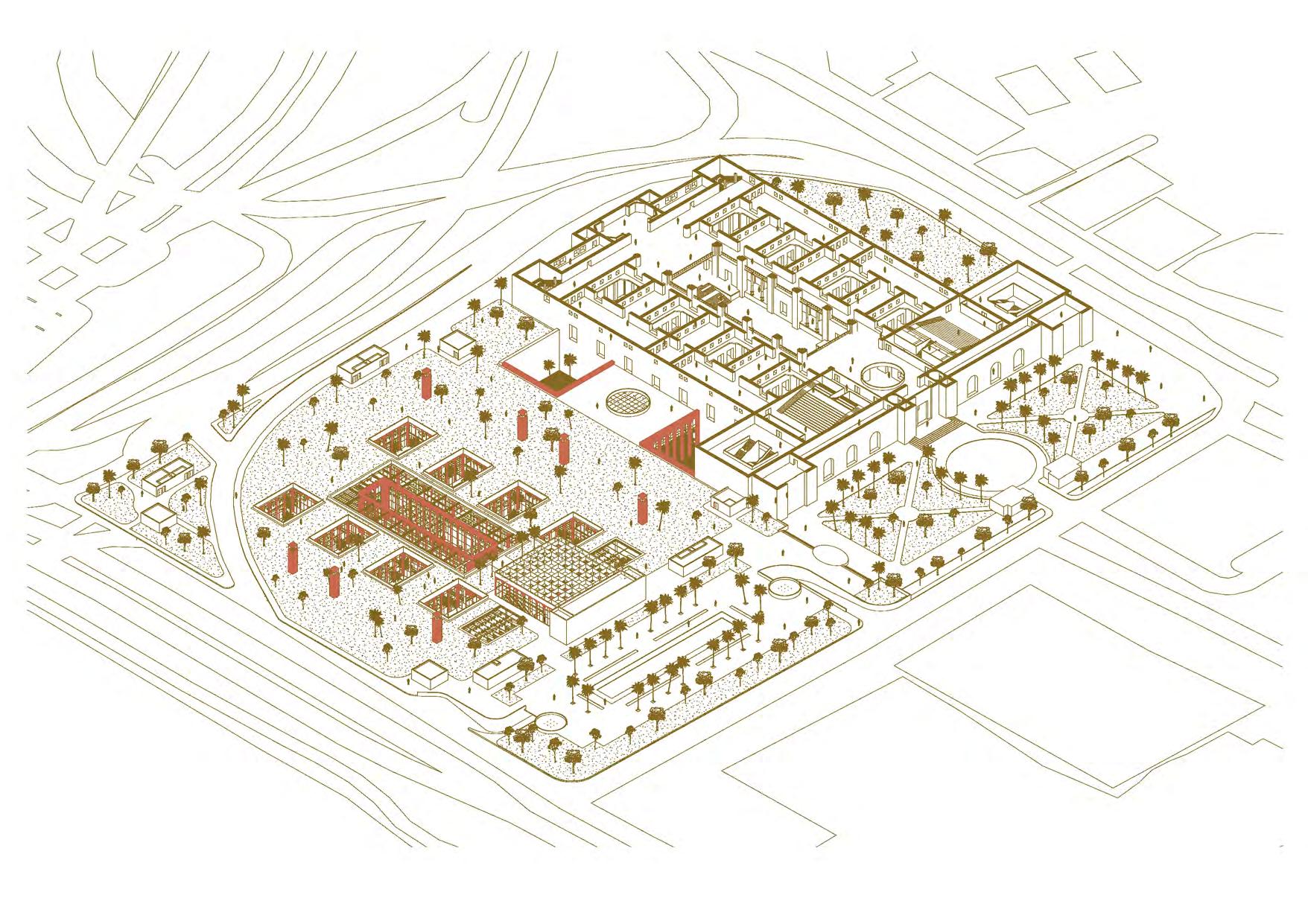

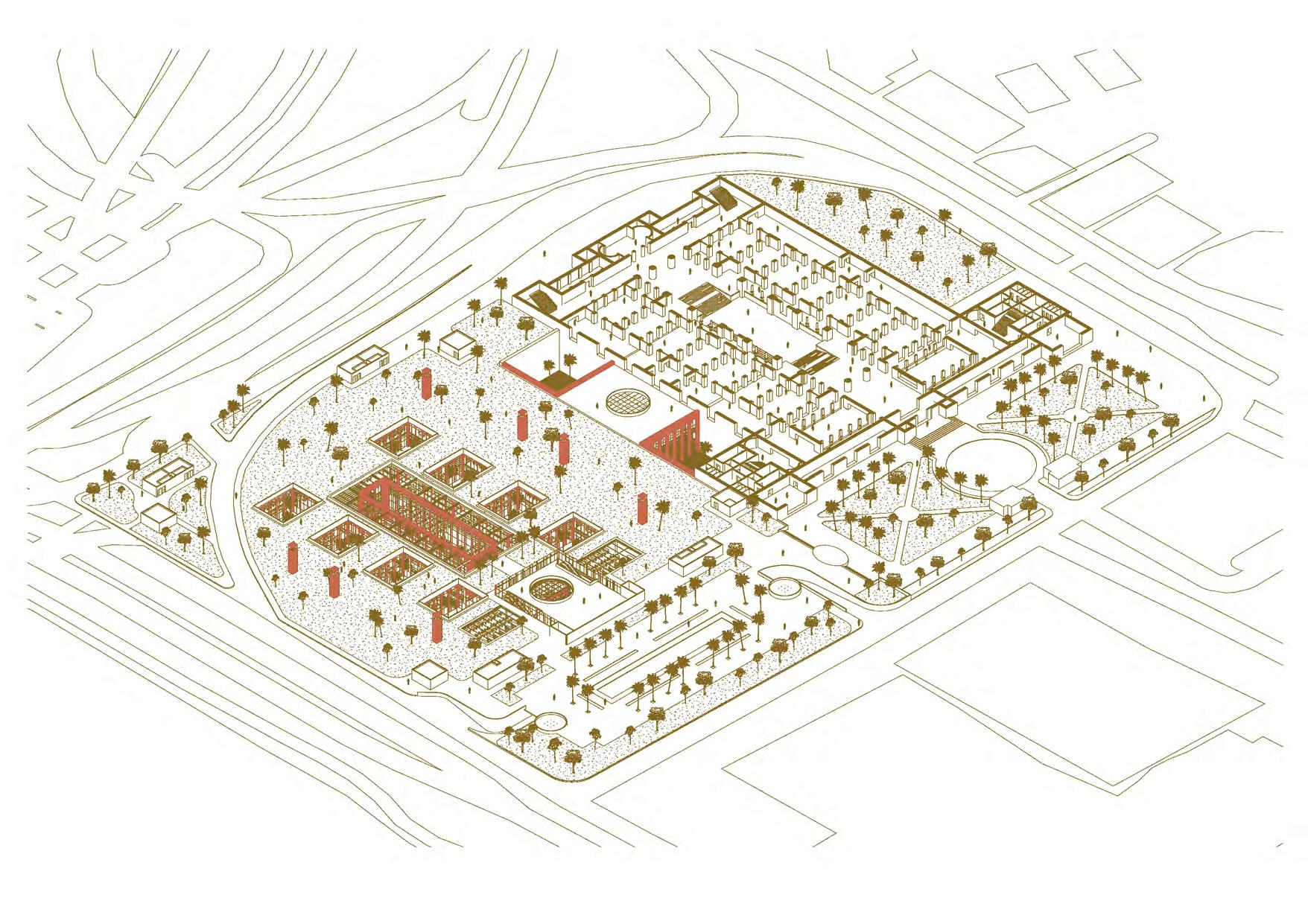

National Library Complex

A. The Context

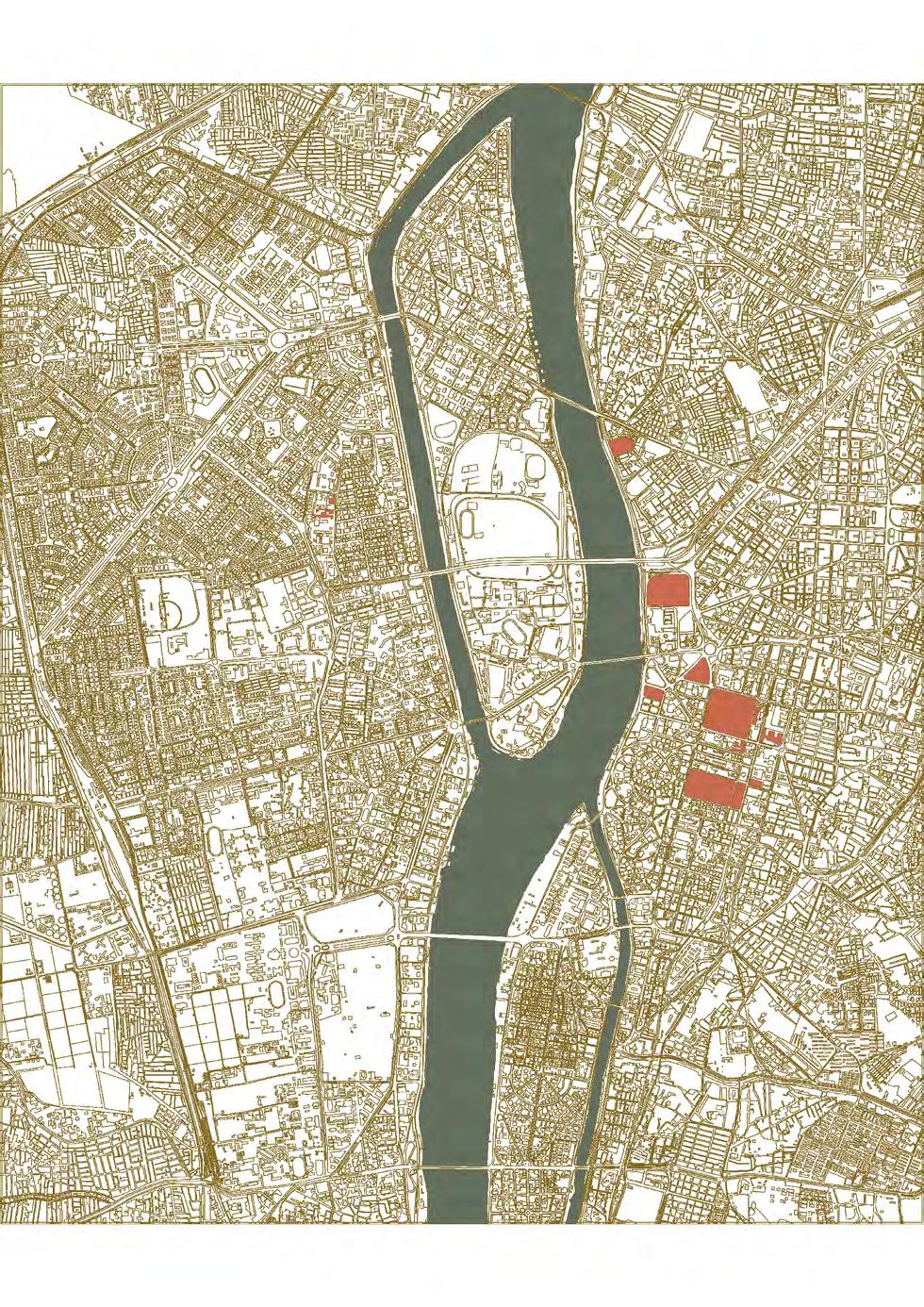

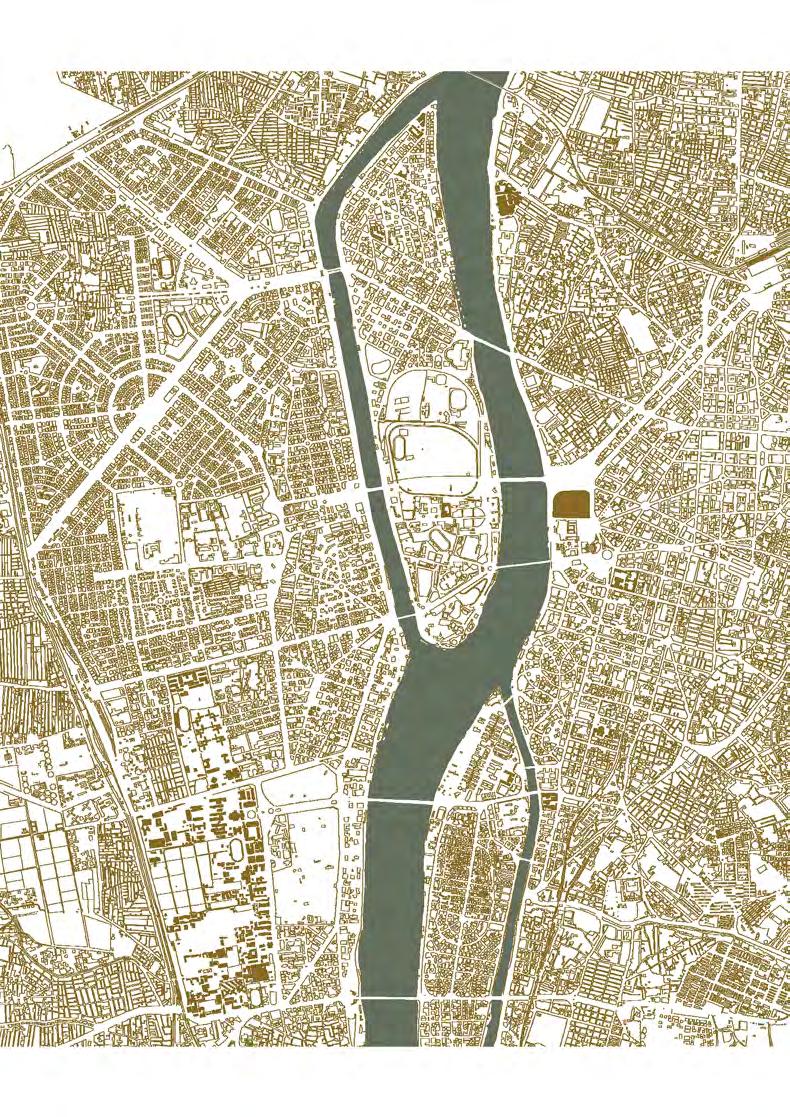

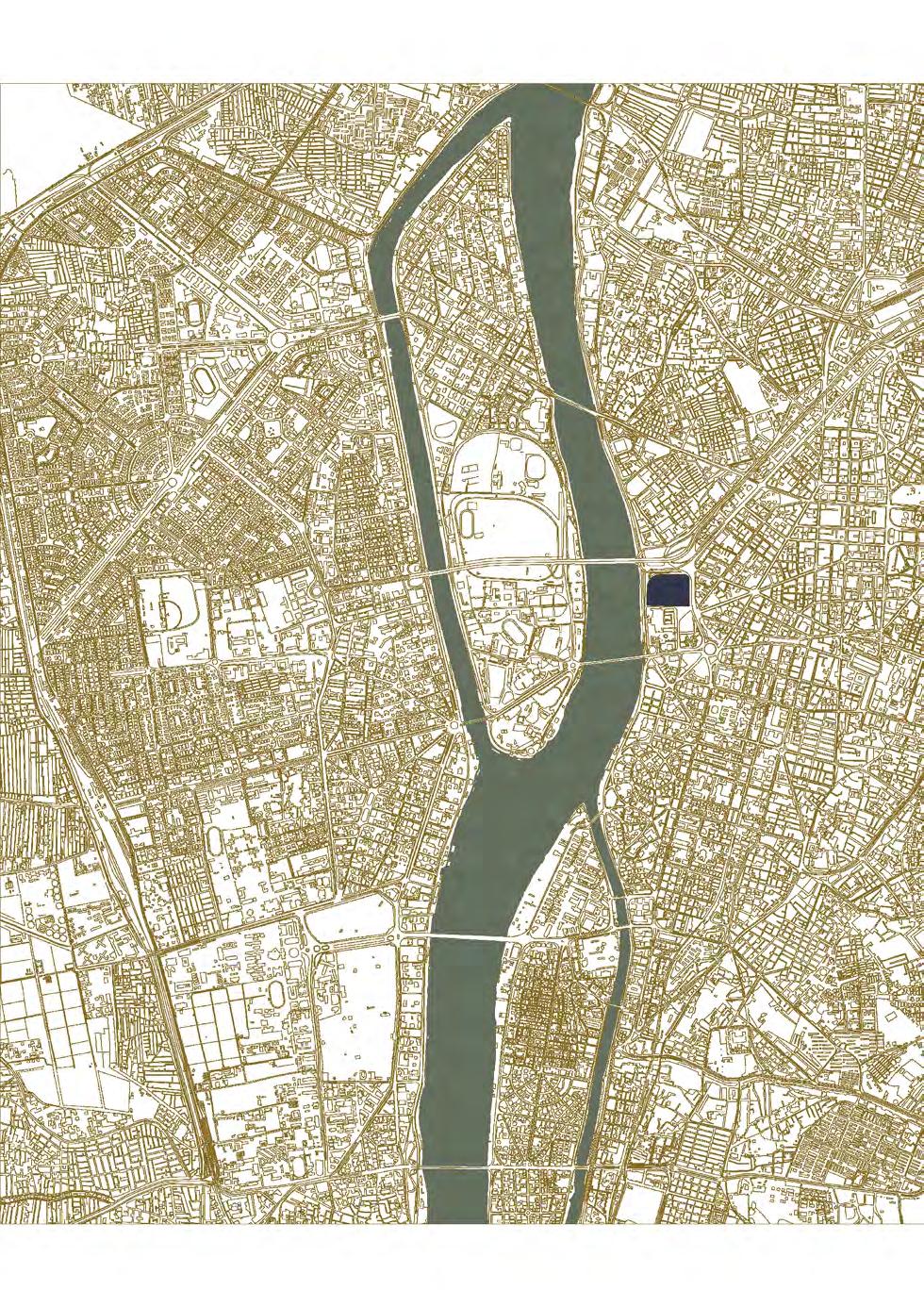

Downtown initially was established as a bourgeois district bordered from the east by the old city with Abdin Palace and the Azbakiya gardens as buffer zones, the south by the Khedival estates, the north by the Ismaelia Canal, and the west by the Nile. The boundaries of Downtown are considered by heritage professionals, urbanists, and architectural historians to be 26th of July Street to the north, Attaba Square to the east, Bab el-Luq Square to the south and Tahrir Square to the west. This denotation roughly constitutes the historical quarter of Ismaelia “the foundations of Khedival Cairo” as defined in Ali Mubarak’s Khitat al Tawfiqiya al-Jadida (Abou Ghazi, 2016). It is often added the adjacent Tawfiqiya and Azbakiya districts to form the familiar triangle delimited by Ramsis Street, extending northeast to Ramsis Square, Gumhuriya Street and the adjacent Azbakiya Gardens to the east, Bab el-Luq to the south, and Tahrir Square to the west.

There is no official designation of Downtown boundaries West el-balad (downtown). It is used by many Cairenes to refer to a broader context that also includes Bulaq, Garden City, and Sayyida Zainab (Ryzova, 2015). The limits of Khedival Cairo, however, have been established by the National Organization for Urban Harmony (NOUH). These bounds include Mohamed Ali Street, Bab el-Luq, Mounira, and Qasr el-A’aini, as well as Ismaelia, Azbaqiya, and Taqwfiqiya.

Accessing Site in downtown Cairo via public transportation is convenient and efficient, thanks to the city’s well-developed bus and metro systems. Travelers can easily reach the site by taking the metro to Sadat Station, which is centrally located and a short walk from the site. Alternatively, numerous bus routes pass through downtown Cairo, with a central stop conveniently situated within a walking distance from site.

1

The plot in question was once the land that used to house the headquarters of the dissolved National Democratic Party 1 lying on the Nile Corniche in Cairo The building was set ablaze during the events of the Egyptian Revolution 2011. Later in 2015 the government decided to demolish it. and the plot remained vacant since then.

Documents possessed by the Egyptian Registry and Land Survey Authority demonstrate that the riverfront property was initially included in the museum’s 1901 construction. Boats carrying antiquities from Luxor, Aswan, and the remainder of Upper Egypt downriver for restoration and museum display used the area as a cargo dock.

Nowadays, The plot is under control of Egypt’s sovereign wealth fund, and was repurposed for multiple uses including offices, apartments, leisure and hospitality before an Emirati consortium won bid to redevelop it, the final signing of the agreement is anticipated in the near future (Patrick Werr, 2024). The development is expected to include a mix of hotel, commercial, residential, and serviced apartment developments (Mohamed Hamouda, 2024).

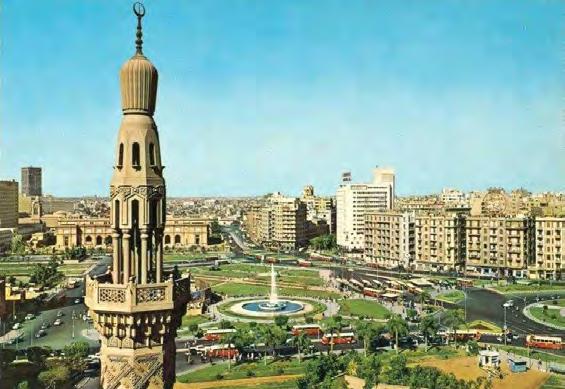

Given its landmark location by the Nile and vicinity to Tahrir Square, which is one of the most important landmarks in Cairo and has been a symbolic place since the 1919 uprising against the British occupation, and has also remained a stage for highprofile political events throughout the last century, from the 1952 revolution to the Iraq war demonstrations in 2003, up to the spring break outburst in 2011, I have chosen this plot as the location for my project proposal.

NDP the ruling party under overthrown President Hosni Mubarak.

The NDP-building after the fire, with the Egyptian Museum in the back.

fig (9)

Site location showing Egyptian museum and the empty plot. (fig. 10).

Postcard, with ‘Downtown’ on the right, the Egyptian Museum behind the minaret and a small part of the NDP-building on the left 1960 (fig. 11).

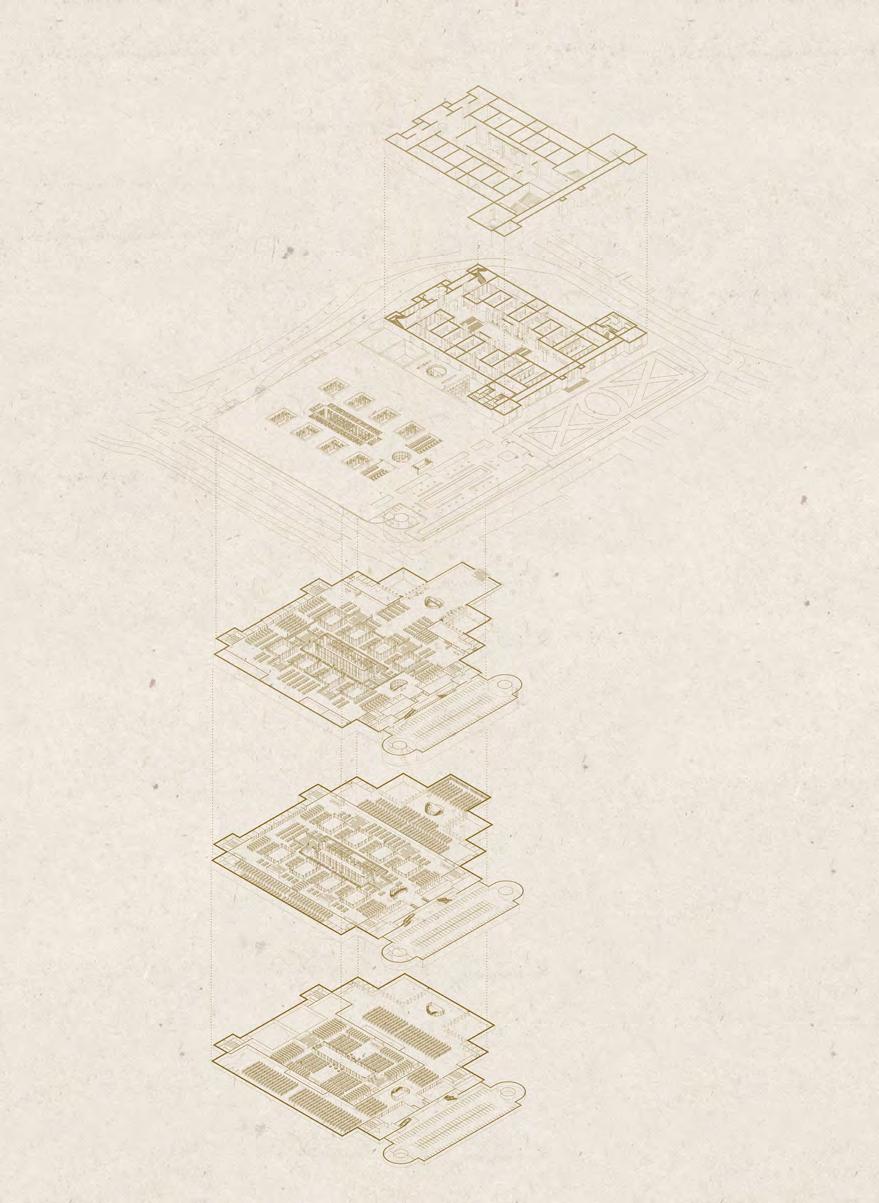

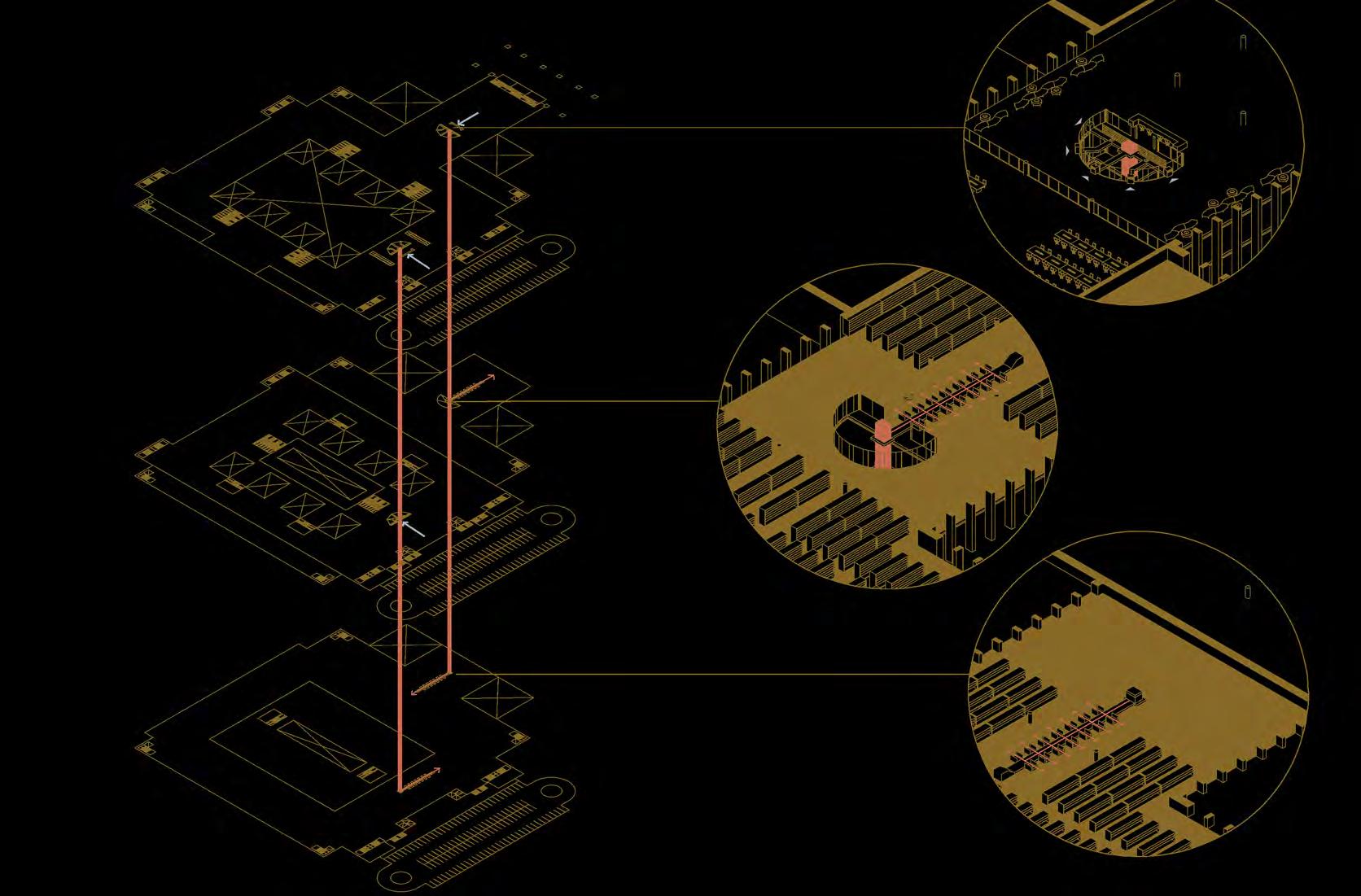

The Theory

We view the process of creating architecture to be additive or accumulative, a process where elements are added in order to create architecture. One brick is laid, and then another. However architecture can also be seen as subtractive, where portions of volume are removed to clarify an entity. In architecture school, we mostly study how to design a structure and make something out of nothing. In a city as dense as Cairo, the need for the void pops up to the surface as one of the first problems facing the urbanistic scene, from there came the idea of thinking about architecture in reverse, doing the opposite. To think about the urban fabric as a whole, a volume, where empty spaces are recognized as a complex multi-layered reality.

I go into further detail about this idea of subtraction in my proposal. In which creating is still the essence but instead of creating something out of nothing, something is being created out of the existing. Each species of Subtraction presents different techniques, motives, and results. The process of subtraction can be categorized into three main types: destruction, demolition, and creative subtraction. A destructive procedure, like implosive demolition, seeks to quickly achieve complete eradication. The demolition process suggests a series of prearranged steps that apply to various kinds of buildings. Events created by Creative Subtraction have the potential to yield a building’s performance’s second or third conceptual framework following that of its intended use. The latest is the one I focus on in my proposal as I am trying to find a new function for the exoisting building and make use of the empty plot next to it without adding more to the dense condition of the downtown urban fabric.

Carving, cutting, demolition, excavation, decay, wasting, obsolences, and reunification are all acts of subtraction that occur in one form or another in our built environment.

“Office Baroque” 1977 Gordon Matta-Clark (fig. 21).

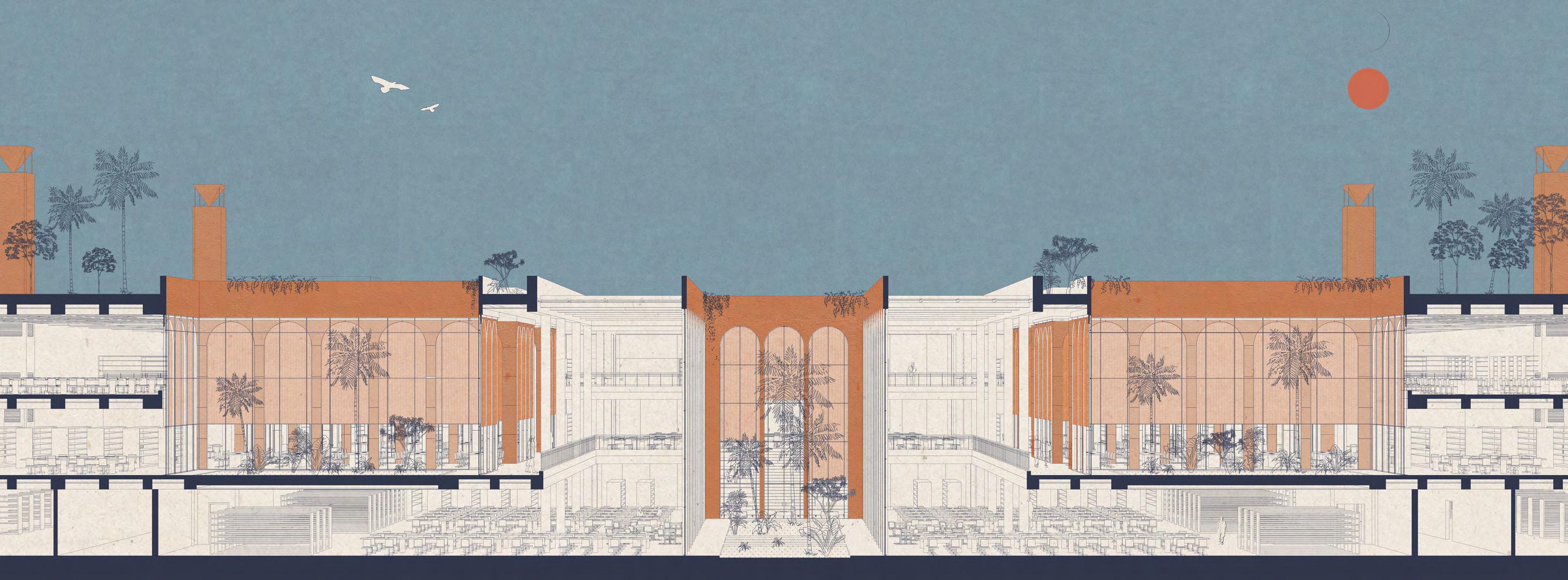

The Design

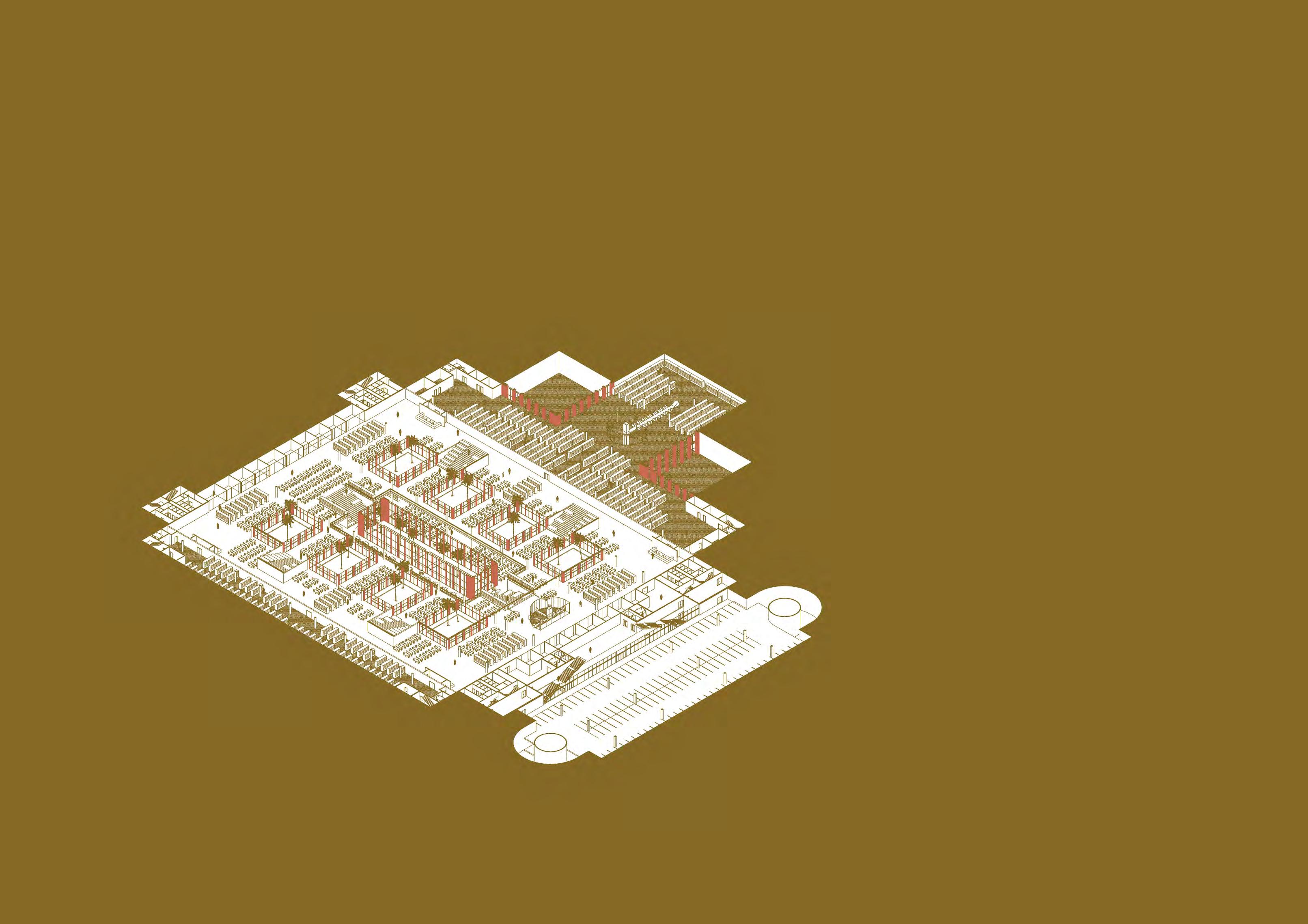

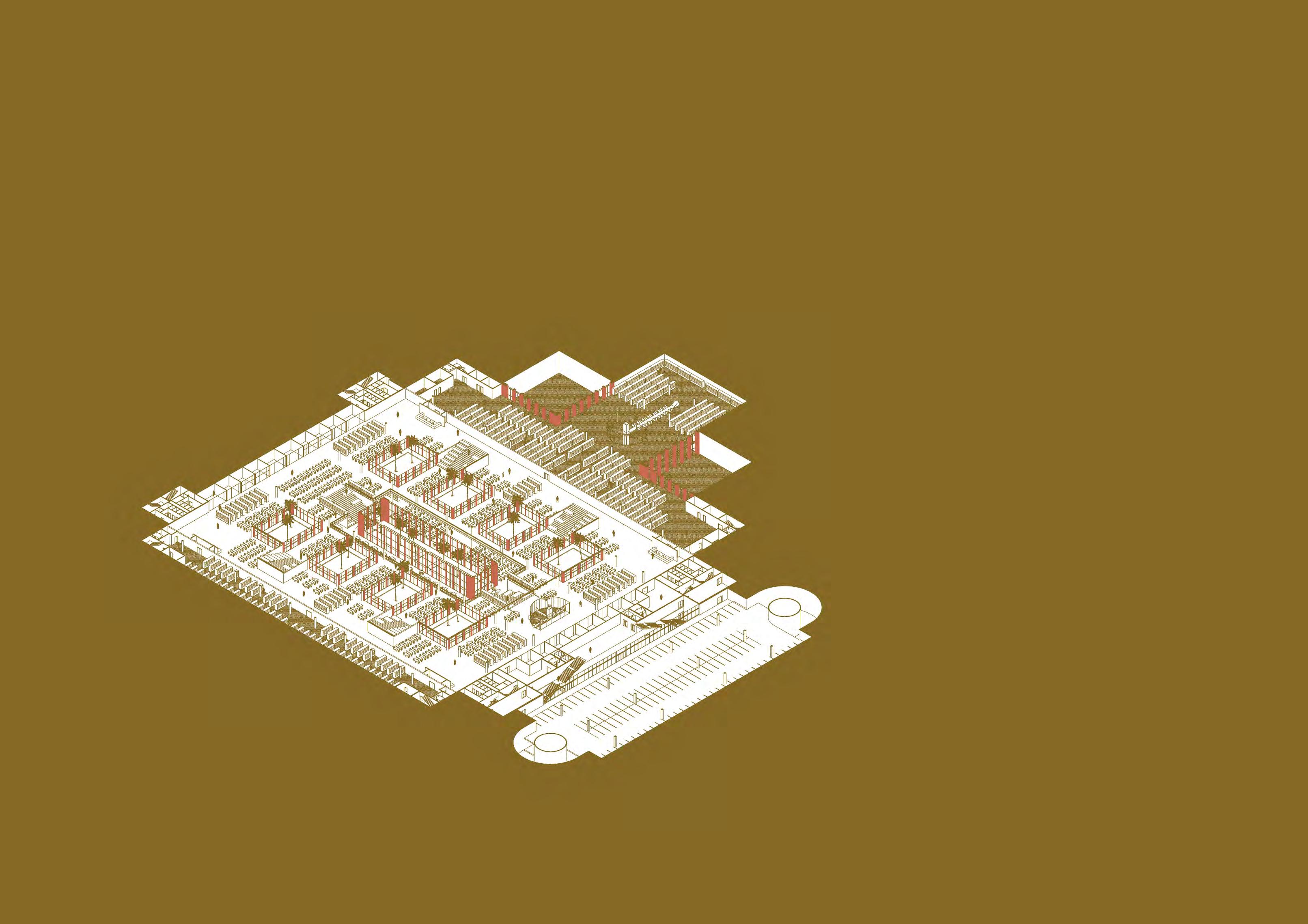

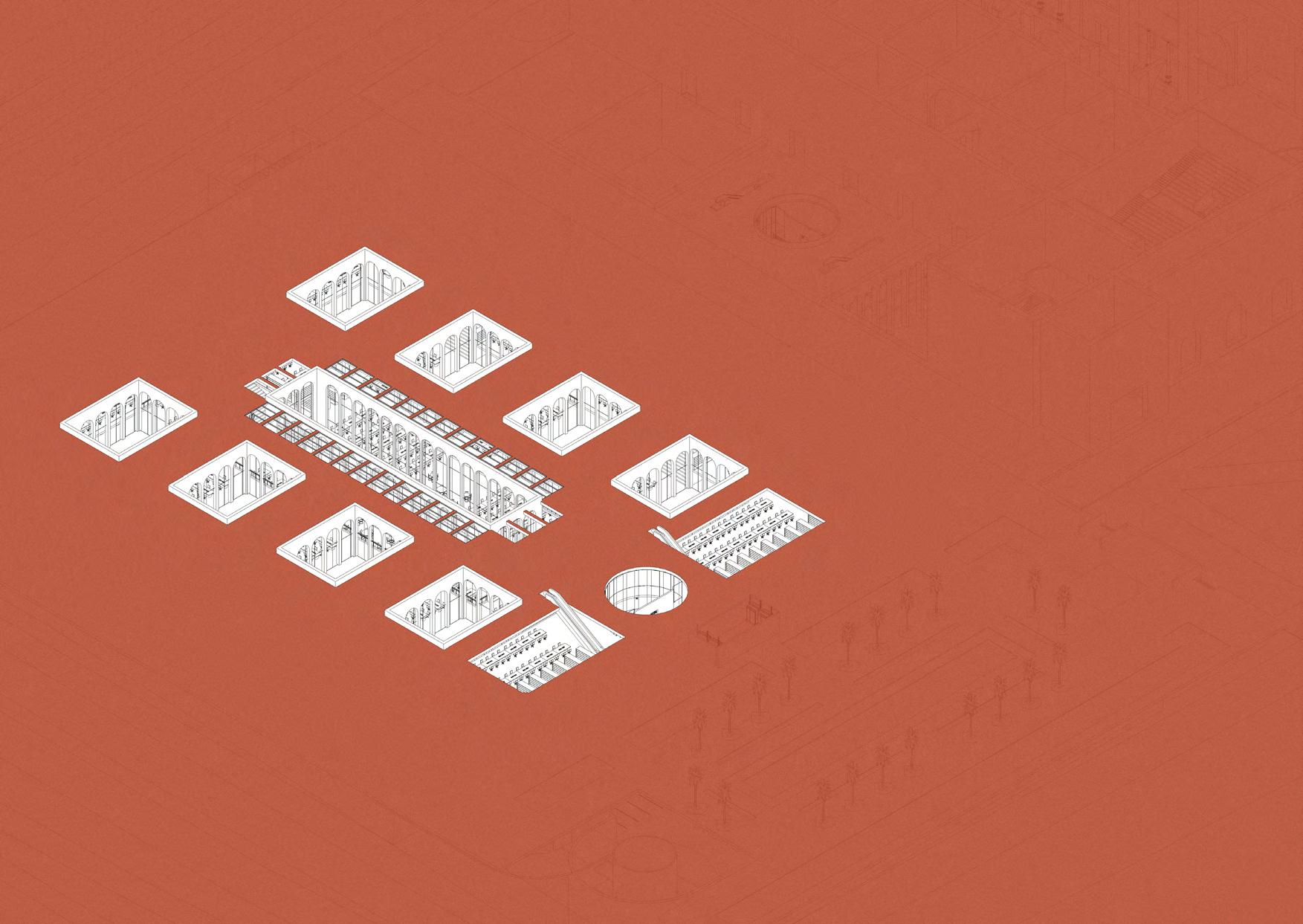

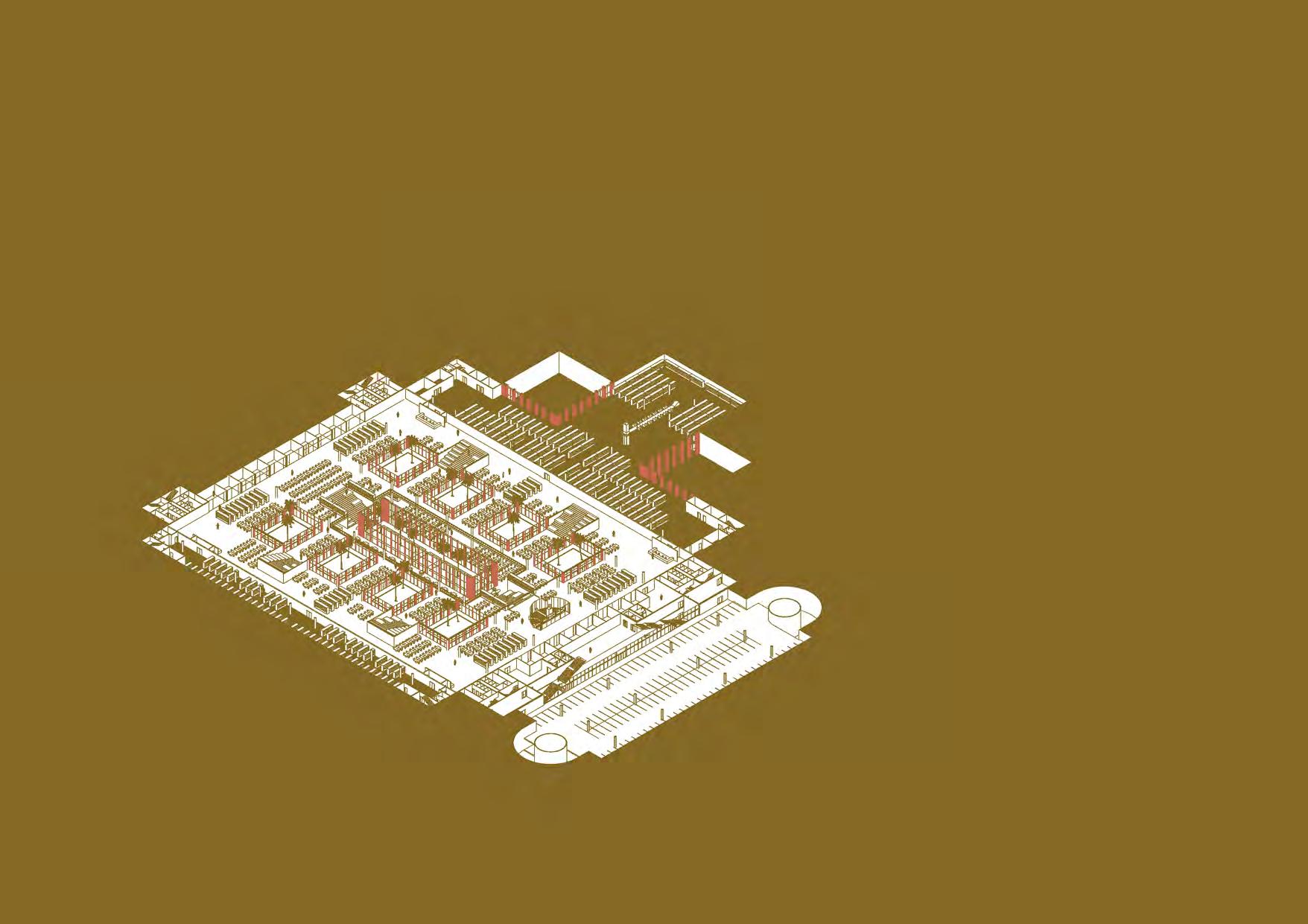

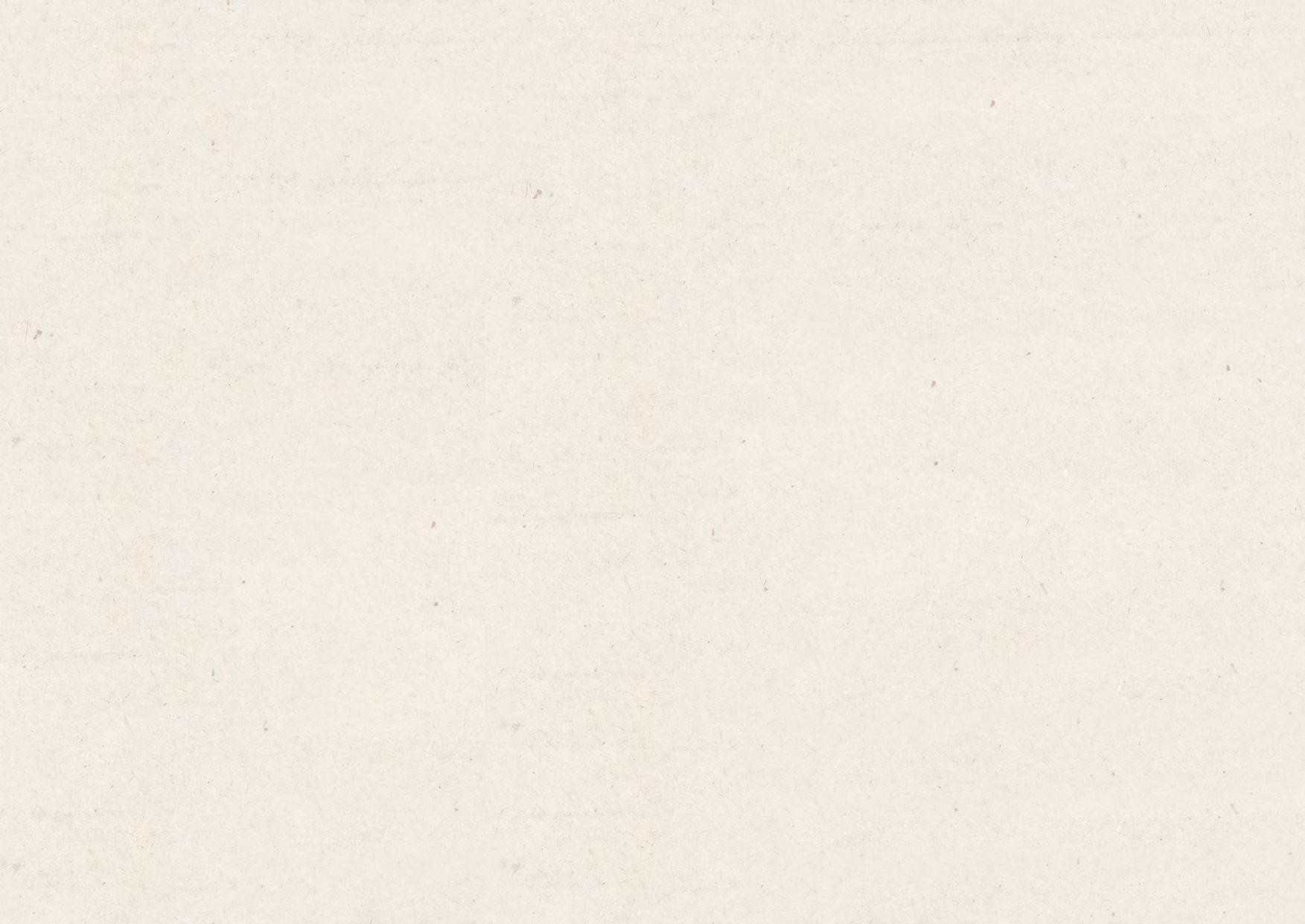

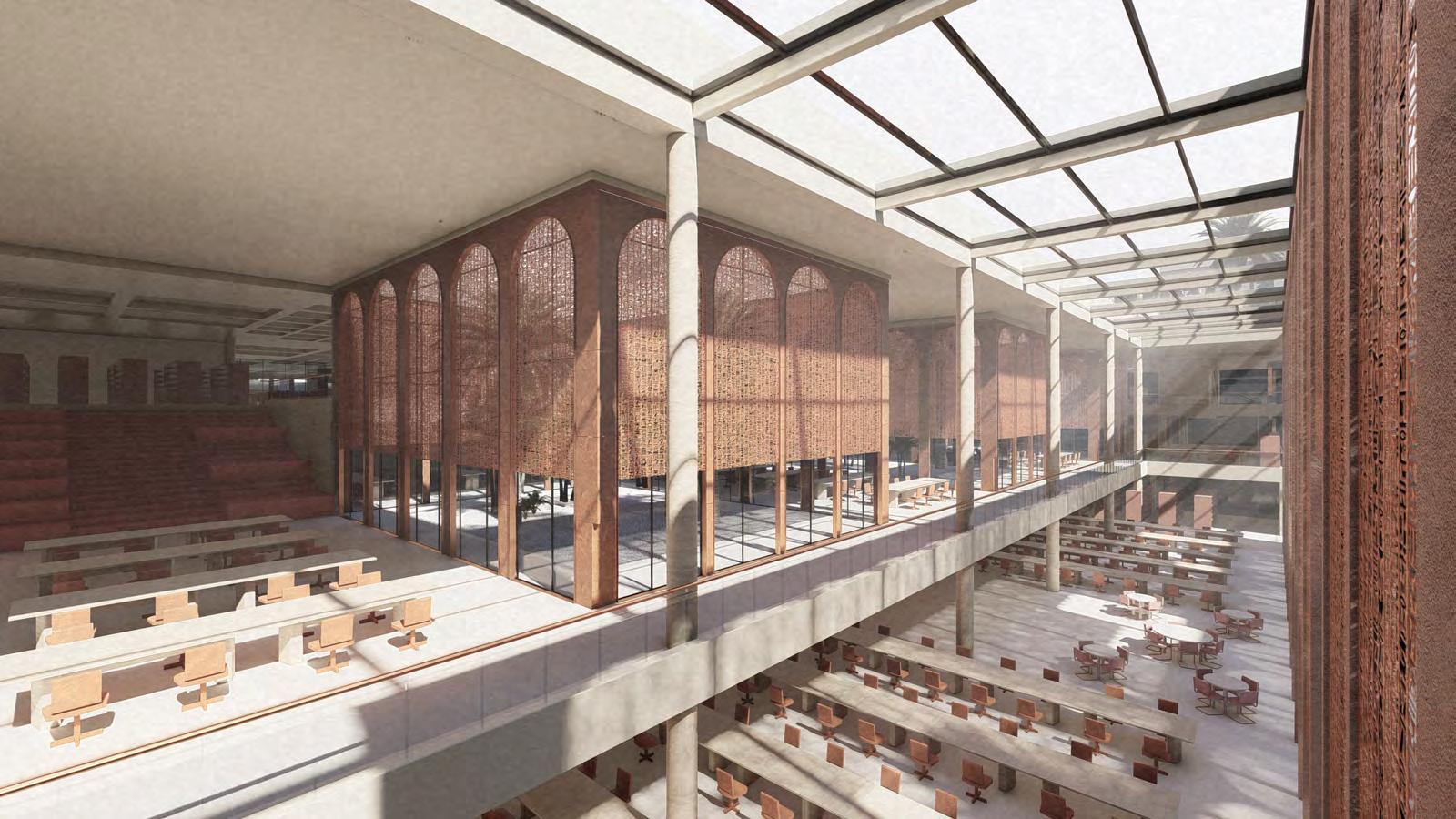

The Egyptian Museum of Cairo goes up on a stretch of land near the banks of the Nile in the old center of Cairo known as West el-balad. It represents a core point for a complete restructuring of this entire part of the city. The massive structure changes from being a monstrous building to a project that involves the void and an initiatory site. A place of reference for the district, a place that could represent the beginning of a sequence of large empty spaces along the whole downtown that give the city space to breathe. This environment serves as a backdrop rather than a riverfront foreground; rather, it will allow for a variety of architectural scripts, the only constraint being that each one must serve as an accompaniment to the institution’s urban effect on its own.

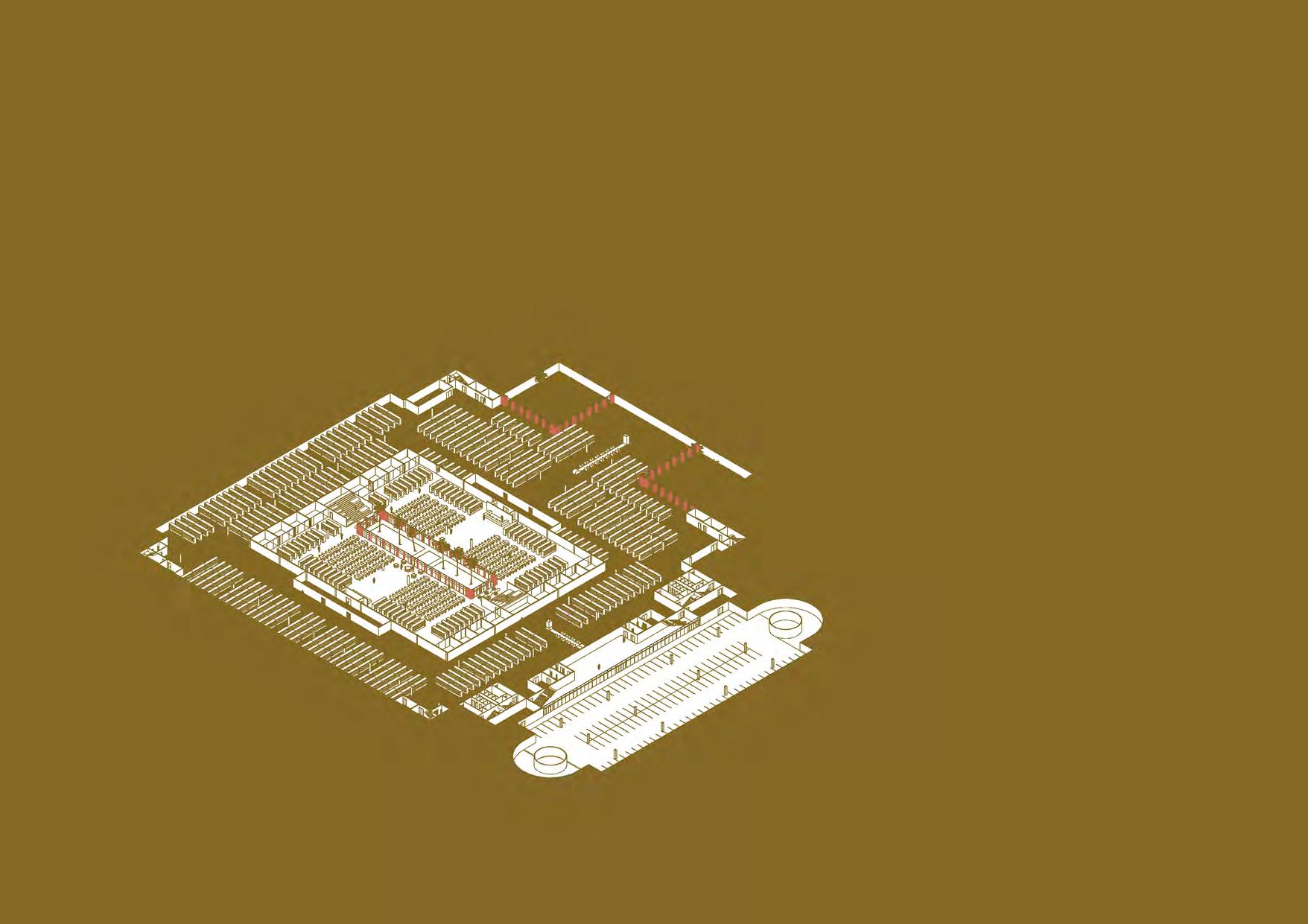

The proposal paves the way for a vibrant cultural future: the creation of a Mixed-use space by ingeniously integrating a subterranean space with the existing museum, employing the principles of the Architecture of Subtraction.

At the core of this architectural endeavor lies a deep respect for history. The Old Egyptian Museum, with its grandeur and significance, embodies the essence of Egypt’s cultural heritage. Rather than allowing it to languish as a relic of the past, the project seeks to honor its legacy by repurposing it as a hub of knowledge and learning—a National Library fit for the modern age. Central to the project’s design is the seamless integration of old and new, tradition and innovation. Recognizing the constraints of space in the bustling heart of Cairo, through embracing the concept of the Architecture of Subtraction—an approach that focuses on creating meaningful void spaces within built environments. Thus, the project envisions a bold solution—an underground expansion adjacent to the existing museum. This subterranean space, is carefully crafted with modern architectural techniques

a key architectural feature of the project lies in the connection between the old and the new. Underground passageways and tunnels, artfully designed to blend with the museum’s historic architecture, link the existing structure with the underground expansion and the Nile River.

Visitors embark on a journey through time as they traverse these pathways, symbolizing the seamless continuity between Egypt’s rich past and its promising future.

The transformation of the Old Egyptian Museum into a National Library represents a bold reimagining of cultural heritage as the library is more than just a repository of books—it is a vibrant community space, where lectures, workshops, and cultural events breathe life into its hallowed halls. This proposal aims not only to revitalize a cherished landmark but also lays the foundation for a brighter, more enlightened tomorrow, utilizing the Architecture of Subtraction to create meaningful void spaces that enrich the built environment without adding more to the density of the area.

The proposal is to set an example of how to use the concept of adaptive reuse of a gap that lies in the main urban fabric of Cairo, considering the location in one of the oldest neighborhoods of the city it shows how to be aware of the context of where you build and try to integrate all the aspects that can be forced upon the architect to come up with a good solution that does not marginalize any part of the society but also revitalize the economical aspects.

The Architecture of Subtraction Theory is encouraged through the sensitive engagement with the surrounding context, respecting the historical heritage and cultural significance of the site. By carving the Library into The empty plot adjacent to the Egyptian Museum, the design honors the existing urban fabric while creating a harmonious dialogue between the old and the new. This subtraction allows the library to seamlessly integrate into its surroundings, preserving the visual and spatial integrity of the historic district.

When it comes to the Spatial composition of the library The act presents an opportunity to craft a series of interconnected spaces that respond to the needs of users while fostering a sense of discovery and exploration. By strategically subtracting volumes from the site, sculpt courtyards, atriums, and passageways that animate the interior environment with natural light and ventilation. The interplay between solid masses and voids creates a dynamic spatial experience, inviting visitors to engage with the architecture on multiple levels.

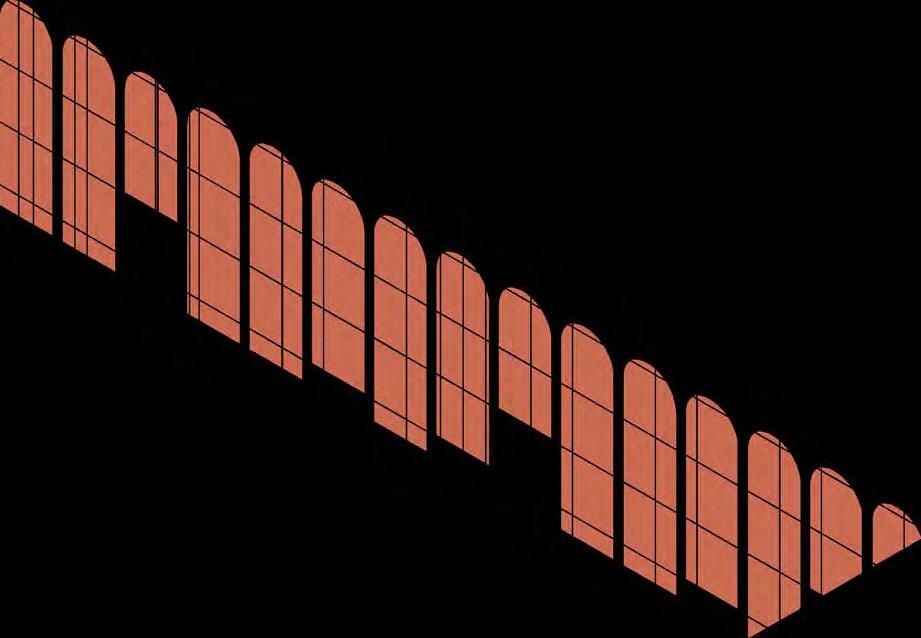

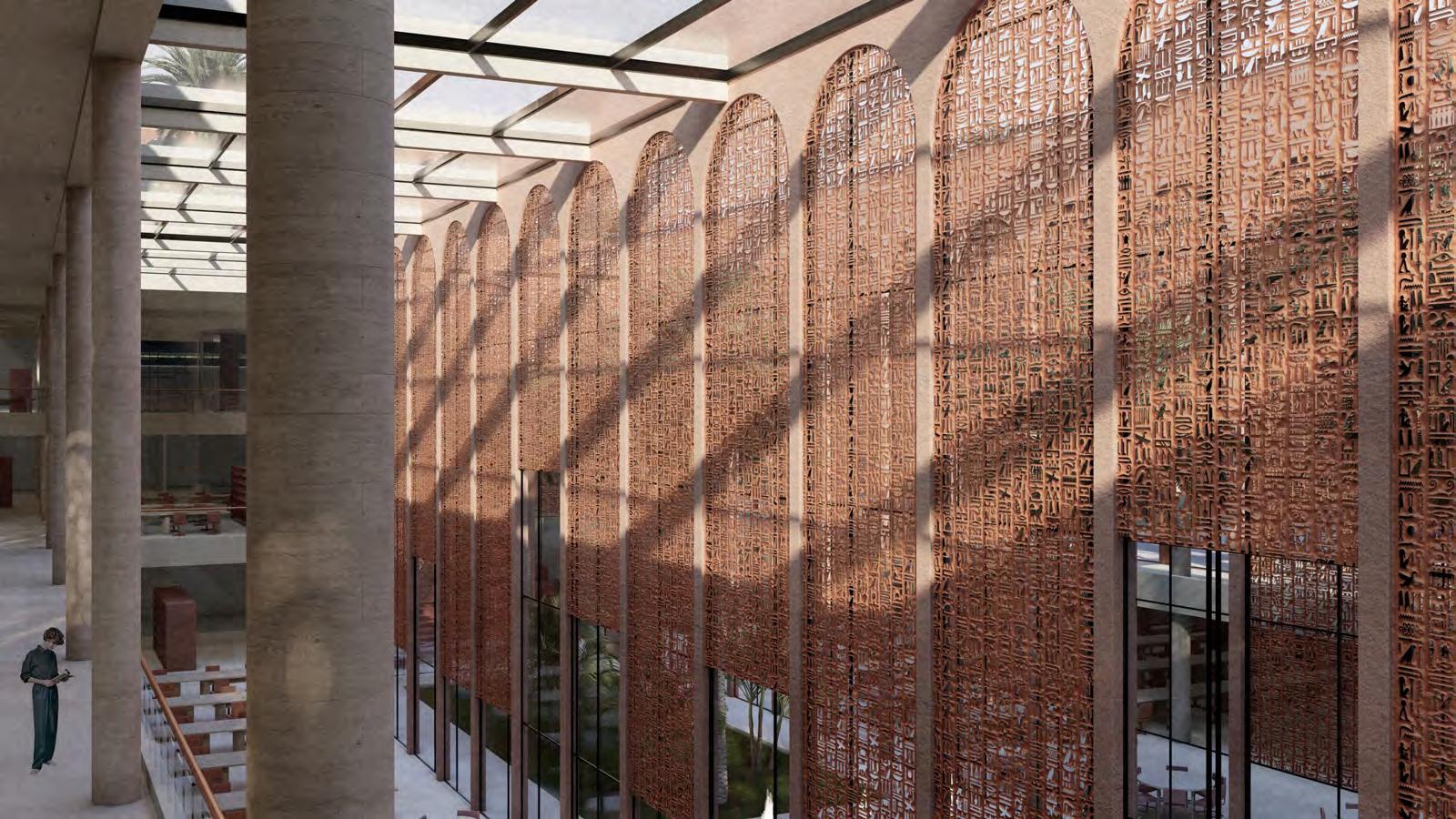

The materiality and tectonics of the project can express a sense of elegance and restraint. Utilizing local materials such as limestone or sandstone and Terracotta reminiscent of traditional Egyptian architecture imbues the library with a sense of cultural identity and permanence. The use of perforated copper panels can be celebrated through the expressive use of negative space, revealing the inherent beauty of the carved volumes and enhancing the tactile qualities of the architecture allowing more light to enter through the patios.

As a symbol of knowledge and enlightenment, the National Library serves as a beacon of intellectual and cultural vitality within the heart of Cairo. Invoking awe and reverence, the design pays homage to the imposing magnificence of the nearby Egyptian Museum while providing a modern interpretation that speaks to the goals of contemporary society. The act of carving into the empty plot can be imbued with symbolic significance, representing the act of uncovering and preserving the collective memory and heritage of Egypt.

The rooftop park acts as a much-needed breathing space within the dense urban fabric of Cairo, offering residents and visitors a reprieve from the bustling streets. By using the roof to create an

The Park

Perforated copper panels render by author

The integration of the rooftop park ensures a seamless continuity of experience between the National Library and its immediate context. Accessible ramps and elevators allow library patrons to reach the rooftop, where they can easily go from the internal reading rooms to the outdoor garden above. The subtraction of the courts from the park creates a sense of openness and expansiveness, blurring the boundaries between built form and landscape and inviting exploration and contemplation.

The rooftop park serves as a sustainable design feature, mitigating the urban heat island effect and reducing energy consumption within the building. The design uses flora, permeable surfaces, and shading elements to take advantage of passive cooling and evapotranspiration, which strengthens the ecological resilience of the urban environment. The subtraction of impervious surfaces in favor of greenery promotes biodiversity and enhances the overall ecological health of the site.

The soil excavated to create this architecture would be reused into the creation of the park, considering the vicinity of the site to the Nile river the, means that the soil is very fertile and could be used for the Roof Park while the rest of the land dug would go to other urban parks around the site.

In addition to its environmental benefits, the rooftop park serves as a platform for cultural programming and community engagement. The space can host a variety of public events, such as outdoor concerts, film screenings, and art exhibitions, enriching the cultural life of Cairo and fostering a sense of belonging and civic pride. The use of the roof to create a vibrant public amenity underscores the project role as a cultural hub and social catalyst within the city.

The Museum open-air green space, the design not only expands the available public realm but also fosters a connection with nature amidst the urban sprawl. The park provides opportunities for relaxation, recreation, and social interaction, enriching the quality of life for the surrounding community.

The integration of museum spaces within the National Library complex embraces the principles of adaptive reuse, repurposing existing structures to serve new functions while preserving their historical and architectural significance. By using the original

footprint of the Egyptian Museum building, it was possible to create flexible exhibition galleries, educational facilities, and archival spaces that celebrate Egypt’s rich cultural heritage. The juxtaposition of old and new elements within the complex underscores the evolution of Cairo’s urban fabric over time, fostering a sense of contin

The addition of two auditoriums within the building enhances its role as a hub for cultural exchange and creative expression. These multifunctional venues may host a wide variety of activities, such as talks, plays, and movie screenings, encouraging intercultural communication and community involvement. The subtraction of material to accommodate the auditoriums within the existing footprint of the Museum maximizes spatial efficiency and optimizes the use of available resources, ensuring that the facilities remain accessible and adaptable to the evolving needs of the public

The addition of cultural spaces within prioritizes spatial flexibility and adaptability, allowing for a seamless flow of activities and experiences throughout the building. The original design of the building as dynamic, interconnected spaces can be easily reconfigured to accommodate changing exhibitions and programming requirements. The integration of movable partitions and modular furniture systems further enhances the versatility of the interior spaces, enabling them to serve a multitude of functions while maintaining a sense of coherence and continuity.

From Museum From Park

Tiles flooring 10mm

Sand 10mm

Concrete 300mm

Cement screed 200mm

Damp proofing 200mm

Concrete 200mm

Insulation 250mm

Drainage 200mm

Soil

Parapet

Waffle

Perforated panels are strategically placed to diffuse the intense sunlight characteristic of Cairo’s climate, By filtering the sunlight, these panels reduce glare and heat gain, creating a comfortable, well-lit environment that is conducive to reading and studying. The perforations allow natural light to penetrate the interior spaces softly and evenly, enhancing the ambiance without compromising on energy efficiency.

Reading areas are closer to the inner courts to maximize natural light while book shelves are more far for book protection natural light during different times of the day

Perforated copper Panel

Metal frame

Metal cladding wall

In dry, arid climates like Cairo’s, where daytime temperatures can soar, windcatchers are particularly effective. Their ability to provide natural cooling without the need for electricity makes them an eco-friendly solution in regions where resources are scarce and environmental sustainability is a priority. By reducing the reliance on modern air conditioning systems, windcatchers also help to decrease energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.

The system is energy efficient for two reasons:

Cool fresh air is drawn into the building naturally instead of using the energy consuming methods used in most commercial buildings.

Beyond their practical cooling benefits, windcatchers also play a crucial role in maintaining indoor air quality. By promoting continuous air circulation, they help to remove stale air, reduce humidity, and minimize the risk of mold and other air pollutants. This creates a healthier living environment, especially important in densely populated urban areas where air quality can be compromised.

Cool wind

Hot wind

Wind catcher detail

IV. CONCLUSION

In the face of rising urbanisation and environmental change, adaptive reuse provides a workable solution to the demands of sustainability, resilience, and resource conservation.

to trigger this concept research had to be done to untangle all the layers and narratives that might affect the decision-making of how to re-use underutilised gaps that are parts of a very complicated yet delicate urban fabric such as Downtown Cairo.

This approach not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of downtown Cairo but also contributes to its economic and social vitality. In summary, by examining political, socioeconomic, and gentrification factors, the hypothetical thesis project emphasizes the significance of inclusive growth and cultural preservation in its comprehensive program to address deficits in the urban fabric. This analysis leads to a proposal on adaptive reuse in Downtown Cairo that seeks to revitalize the area..

Additionally, the project recognizes the potential downsides of gentrification and suggests ways to mitigate its adverse effects. by finding a balance between economic development and cultural preservation.