Summer 2024 - Journeys

Summer 2024 - Journeys

Indian Ocean by Auberon Dragten (Year 10), Harrow School

A Bird’s Girl by Isabel Leale (Grade 10), Harrow Bengaluru

The Right Path by Grace Chan (Year 7), Harrow Hong Kong

Forgotten by Ashley Tam (Year 10), Harrow Hong Kong

The Journeys of a Speck of Humanity by Arthur Yang (Year 11), Harrow School

A Ray of Hope: The Journey to Aishu’s Freedom by Aneeka Jayasimha (Grade 7),Harrow Bengaluru

The Invitation by Mac McDowell (Year 11), Harrow School

The Great Filter by Helen Zhan (Year 12), Harrow Shanghai Journey of Life by Chloe Terrettaz (Year 11), Harrow Shanghai

The Journey to Find the Golden Fleece by Nga Kiu Ho (Year 10), Harrow Hong Kong

Eternal Distance by Moulika Basima (Year 12), Harrow Shanghai

Playing The Poet by Nicole Lau (Year 12) and Bess Chau (Year 13), Harrow Hong Kong

Journeys by Nara Chenyavanij (Year 12), Harrow Bangkok

The Old house by Emily Wang (Year 10), Harrow Zhuhai Journey to Gaumukh by Anushka Ganesh (Grade 7), Harrow Bengaluru

A Hymn, A Requiem by Jonathan Song (Year 11), Harrow School

A Purging of Memories by Kawisara (Venice) Prapaipichit (Year 10), Harrow Bangkok

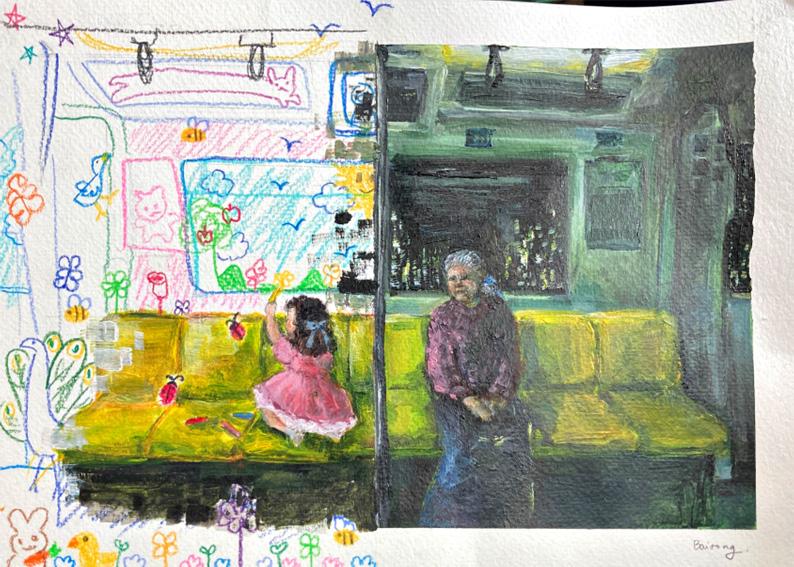

The Human Race by Baikaew (BK) Thanbancha (Year 11), Harrow Bangkok

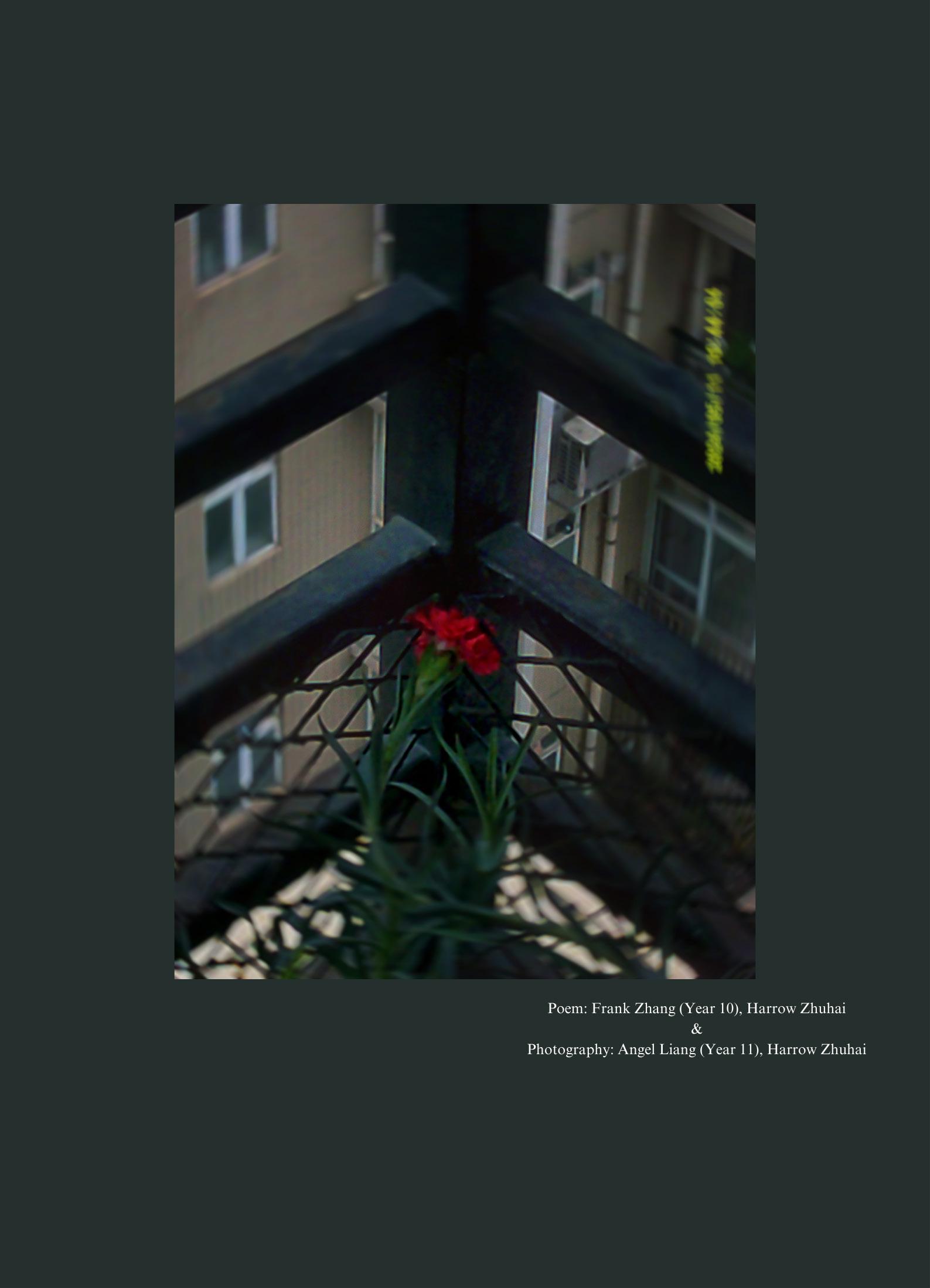

Attempting to Connect with My Ancestors by Vanessa Ho (Year 10), Harrow Hong Kong Shooting Stars by Nita Charoensuthammas (Year 6), Harrow Bangkok Interstate No. 5 by Jonathan Ford (Year 11), Harrow School 2337 by Moroti Akinsanya (Year 9), Harrow School Snow Fall by Max Walton (Year 11), Harrow School The Rescue by Wesley Leong (Year 11), Harrow School Dani’s Question by Jack Showell-Rogers (Year 9), Harrow Bangkok Via Mala by Lee Brogan-Shaw (Year 9), Harrow School From Endings, New Beginnings Rise by William Fung (Year 10), Harrow Zhuhai Plumule by Frank Zhang (Year 10), Harrow Zhuhai The Beginning of the Seas by Lars Wang (Year 10), Harrow Zhuhai

This moving creative writing anthology captures the essence of the many journeys that we take in life. From epic adventures that span continents to commentary on personal growth, this collection encapsulates how journeys shape our lives.

We are overjoyed to present the hard work of all our contributors, writer, teachers, editors and artists. We hope that you find inspiration in the work produced.

Andrew Arthur, on behalf of the Editorial Team.

This Issue is Edited By:

Andrew Arthur (Year 13), Harrow UK

Dominic Rapley (Teacher), Harrow Hong Kong

Amy Rompotis (Year 13), Harrow Hong Kong

Jo Cole (Teacher), Harrow Bangkok

Jessica Lancaster (Teacher), Harrow Shanghai

Jacqueline Cairns (Teacher), Harrow Bengaluru Angel Liang (Year 11), Harrow Zhuhai

Gratitude is expressed to the many other student editors from the various other schools who are not named here.

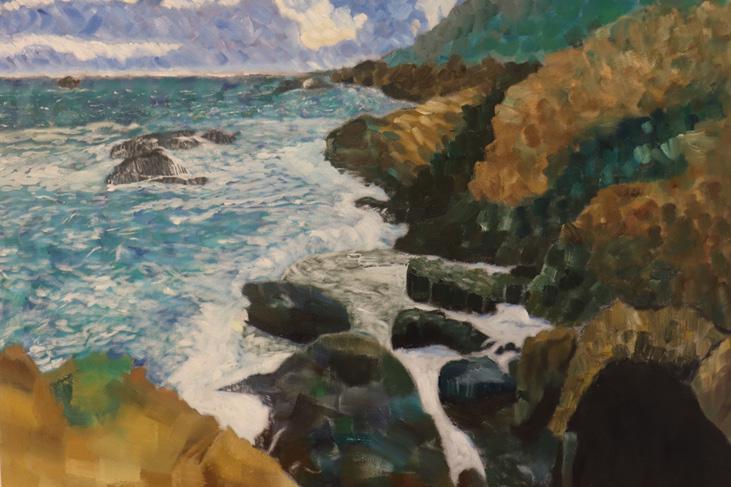

By Auberon Dragten (Year 10), Harrow School

Artwork by Felix Regnard-Weinrabe (Year 12), Harrow School

A pitiless gale hurled huge swathes of spume in the night’s murk. Our hull, weakening by the second, was pounded relentlessly by the hungry sea; the sails -torn by the torrent which bore down from the heavens- whipped the bitter winter’s air.

‘We’re lost!’ Judas wailed in muffled Portuguese ‘Oh heavenly father, save us!’ I could not tell whether it was tears that emerged from the yellowy swollen holes of his sunken eyes, or simply the rain which had become one with the howling wind. Nonetheless, his legs gave way as he collapsed to his knees. And then the decisive wave arrived. The whole sea seemed to shudder as the deep blue gripped the ship and dragged it inexorably to its demise.

Darkness consumed me. A silence which ravaged my ears so that they might bleed rang out, and I was swept away into the blackness.

When I awoke, I could feel every sinew shifting in my muscles, weakened by the months at sea. Although internally writhing in pain, I forced myself to my feet, trying to focus; my vision reeled uncooperatively, my eyes in intolerable agony. Eventually they came to, and I looked up, wanting to verify the sand which I felt shifting between my toes. Sure enough, I was ashore. Not dead but close to it. As far as my blurry vision could decipher, I saw sand, elegant dunes mingling in the orangey red light of sunrise. In comparison, Portugal was made to look like a lifeless mass of mud and concrete. The Portugal I once viewed as the pinnacle of all human achievement and beauty stood quivering under this single rising of the sun.

Just a few feet to my right I made out a lifeless corpse, then another, three more following. Judas amongst them; he was dead. I remembered vaguely the excitement with which we anticipated our first voyage, since we were young it is all we had ever dreamed of together. How we longed to be rid of the firm ground and to meet the more secure swaying of the ocean, to look out into the vast and wonderful unknown. We were headed for China, a journey to conduct trade and bring home the spoils of our endeavours. I had heard of Arabia as everyone had, since its almost miraculous discovery some decade prior. But I had never intended to arrive here. I tried to recall the horrific events of the night before but to no avail, I could hardly breathe under the stifling weight of this hot, heavy air which forced itself down on me. I longed for the release from this painful existence toJudas moved.

I saw it, I was certain of it. Judas had moved and I was flushed with a surge of hope. All agony seemed to dissipate as I lunged toward him. He sputtered and wheezed, coughing up heaps of water and sand.

A few hours had passed since we awoke. The heavy smog of despair had washed back over me with the reality of our circumstance. Everyone else was dead, we had no crew and barely any rations, a single flask of water which might last us two days. Death encroached us. Satan’s hand loomed over my head as God looked down in disgust. Even He wouldn’t be able to save us now. It was a typhoon. I had heard of the great monsters from the east. We had seen glimpses of their destructive capabilities in Portugal, none of which could be compared to the vigorous potency of what I had experienced. How the waves had climbed to the heavens only to come crashing down once more, how the wind had wailed in pain as it was battered by the salty rain, how my eyes had been blinded, my senses numbed, and legs weakened. We had been swallowed by the treacherous sea. Now we would be swallowed by the sands of Arabia.

By Isabel Leale, Grade 10, Harrow International School Bengaluru

She was young when she first came to see me, rife with unfettered joy. A child, meaty fingers clinging to glimmering bars as she desperately leaned forward. Nose tip turned white, cheeks bulging as she peered into the depths of my little gilded prison. Perpetual wonder marked her face, desperate to escape the confines of human life and enter my own. Her eyes glistened wide with vitality, in the light of the incoming morning rays filtering through tall windows into the room, digits gripping as if trying to grasp at the freedom I seemed to possess. So carelessly innocent. She peered in towards me, an alter to Elpis, trilling among the rays of the sun, my only pastime among meaningless hours. So I spent my days, punctuated only by that girl at dawn, a daily visitor, a burst of energy and brightness, among the dark monotony of my simple existence. She’d sit and watch me sing my song, the wish of freedom among my many hopeless days, awe in her eyes at each new note. To think that she envied me so, even as I yearned for what she possessed, a place beyond these bars, a chance to experience life, not this… existence. We were a painful contradiction; her sparkling eyes and tinkling laugh the perfect foil to my melancholy tune.

She would join me every day. But each time a little later, a little quieter. Soon the morning rays in which she greeted me warmed into the mid-day light, then gave way to a silvery glow, the moon leaking in through those windows bleaching my bars to a dim grey. They blended with her now pale face as if the fire that once lit her from within had been dampened to ash. It was filled with tension, shoulders hunched, as if she too felt the weight pressing on her, like the confinement that bound me. The quips and snipes of her peers, adding to that impossible burden. The need to mould her into something she never was and never will be, crippling her at the legs. Deeper and deeper her eyes sank into their sockets like a weary moon sinking among the purple and blue bedclothes of an ominous dawn sky. With every visit she made, she became disenchanted – no longer enraptured with my ritual coo. Staring as if blind through the mist of the arched windows, she became like a wraith – almost incorporeal – until she did not come at all.

The last time I remember clearly, frightened by her ignition of emotion after so long of a void. I remember being almost relieved to see even a spark of some emotion- anything. She stumbled into my room, a flurry of white, flapping skirts and fury, her own skin seeming as discomforting as the frock she wore. Eyes glistening not with pain, she stumbled forwards tripping on her hem, but continued towards the shelves of books lining the wall. She tore them from their refuge, spines cracking and paper ripping, glass shattering at the impact of a hurled volume against a window, a thousand manila leaves floating, lazily from right to left, towards the floor. They surrounded her in a falling halo, she crouched in the devastation’s centre, their papers asylum from a million invasive eyes. She curled over herself, hands clutched to her stomach, nails scoring lines deep into its ruffled grandeur, to the hard girdle beneath.

Motionless in the aftermath of released emotion, she was the single stationary object among the flying papers and lazily drifting curtains, in the gentle breeze of the cracked window and the salty tears dripping sporadically onto the floor. She sat there for minutes until once again establishing dominance over her face, that now returned to that vapid mask. Unflinching at the destruction that saluted her as she lifted her bowed head, she rose and left. I mourned the words I could not utter while she

was still close enough to receive them. That I could not comfort her, bound as I was. Now it seemed as if she was the one trapped behind bars, stuck among the displeasure of flimsy cordiality and basic insincerity that limned her world.

In the absence of her companionship, swathes of shadows were now my only indication of time. Strips widening and thinning, their circadian rhythm my only compass to traverse the long hours spent alone. The days grew shorter and longer then shorter again. Dew now made home on my cage, breaching the glass of the window, unfixed even after so many months. Each was a bead of pearly opalescence, their orbs witness to my sorrow, a mute companion to my unceasing solace. Steady in their posts they stood frosty vigil, even after my voice turned to a shrill croak and the colours faded from my feathers; even after my dreams of freedom abandoned me like wilted petals falling upon barren soil. Constant among the inconsistency of human emotions, their unwavering grip turned the cage to rust.

I sat there for years. Until another little girl with wide unbroken eyes and misty breath, came upon me. Chubby fingers clutched at the brittle bars that now crumbled away under the pressure. Granules of metal slipped between her closed fists. She stood before me, wonder moulding her face into scrunched eyebrows and parted lips, a slight flush to her red-tinted cheeks. I looked down upon her, the frost in my eyes thawed by her own’s adulation. Her stare rightened my purpose, returned that warmth.

A voice cracked with age called from beyond, breaking our gaze and summoning her away. She left and I was alone but not as I had once been. Now I was open to the escape I had craved for so, so long. Though, at the back of my mind I wondered if the world I went towards was even that.

I jumped. Jumped from the shell of silence. Racing towards the sun itself, I was alight in the pure rush of it all, until my own liberation was snatched away with the flash of a single spark. Loathsome death embraced me with the imtimacy of cold iron. A single pellet was enough to snuff out the light of such insubstantial freedom. I was falling down, down, down, and the Earth came up to meet me once again. ***

The girl – now woman – sat there with her daughter, as she watched the familiar bird plummet from the sky, like the stooge of some divine ploy. The girl beside her now clutched her hand in horror at the fate she had sealed, for no sooner than she had let it free, it was pulled back by the constraints of fate. And the cage now stood empty, its bars no longer a barrier to hold the bird captive, it was not freedom that girl found but loss. Let her learn this lesson young, the woman thought, after all as the years passed like grains of sand through her fingers, there was one thing she had discovered. Some bars were not made from gold, silver or even steel, sometimes it was just the strings of fate had pulled you onwards, the journey of life autonomous and its destination that of inescapable death.

Written by Grace Chan (Year 7), Photography by Valerie Chow (Year 13)

The Girl:

The Right Path

I come to a junction in the long, winding road I shall take the right path

But which is the right path?

They blend until I don't know which is which

Red or blue

Lies or truth?

Left or right

Darkness or light?

I know that the path on the right is good

But it is covered with thorns

So I take the other

Chaos

Dread awaits

Filled with gloomy storms and murky shadows

Whispering regret into my ears.

The next junction comes I choose more carefully

On one side is a pit of flames

On the other is a field of flowers

The choice is obvious

But

One jumps into the flames why?

Others come and all do the same

Where I see suffering

They see pleasure

Are my eyes seeing wrongly? am I the only one?

Everyone is cheering as I touch the flames

But it's still

Hot, painful, searing fire.

Hot as the sun

The cheering turns to jeering

When they see me run

I fall

But it is not the end of the road yet

So I will keep walking and walking and walking

“Alice! It’s time to go! You’ll be late!”

Distressed shouts fill the house, droplets of agitation slowly choking me. Packing up my entire life into four boxes is an arduous task, a symphony of memories swirling around me like a tsunami, sweeping me up, tumbling and turning until I’m sick to my stomach. Every video I’ve watched gushes over the freedom and the new experiences and the excitement of college, but I can’t help a sinking feeling of dread diffusing into every part of my being. Old notebooks from Year 3 floor. On the next page, the with scruffy handwriting and foolish doodles sprinkled around lay opened, scattered on the names of friends and classmates that are nothing more than a hazy memory, shrouded in the fog of time. Another cupboard, my pink cooking set from kindergarten. Even after fifteen years, the afternoons of tea parties and joyous laughs are not lost on me. How could I ever leave all of this? Everything opens a door to my chamber of memories, from diary entries, to secret crushes, to my childhood. How could I ever leave this behind?

“Alice, it’s time to go! What’s taking you so long? Get in the car or we’re leaving without you!”

I’m left with no choice. I shut the cupboard, the pink cooking set collecting dust, as I push those memories down further, once again imprisoning the slivers of colour on my bleak canvas of life. Then, I tape the boxes up, a random assortment of trinkets and objects I think I might need. Taking one last look at my childhood room, my safe haven, my home, my life, I leave, shut the door and walk reluctantly to the car. I try to bask in the illuminating late summer sun, but an aching pulse of dread seems to latch onto me, unwilling to let go. —-

The Teddy Bear:

The door shuts, and silence ensues. I’m left on the shelf, patiently and silently waiting. I hold on to the faint glimmer of hope that she’ll come back for me, for all the memories she’s made. Embedded in the worn threads and matted fur, trapped in the saggy left leg and the eye that fell out, are her first-times, her experiences, ones that I assume mean the world to her and more. Maybe it’s false hope, clinging and grasping onto a time so vivid to me, but nothing more than a minute grain of sand in her hourglass.

Time seems to lengthen, days and nights blurring into one another as I sit in her stagnant room, untouched and unchanged, my mind constantly wandering to the times when I was needed and when she cared. That night in bed at 8:43 all those years ago. She won a class writing competition that day with a wonderful acrostic poem about rainbows, how it comes after rain, like how good triumphs over evil. Her chubby arms and fingers clenched onto me tight as her eyes gleamed with pride, a gloating smile dancing on her lips.

Or that night when her childhood crush rejected her dismissively and she soaked my stitching in her salty tears. An amalgamation of snot, cries and the blubbering words of a child in grief seeped into my stuffing, her swollen eyes and pink nose burrowed into me, like I provided solace. Me, a brief impenetrable bubble of protection. I was her comfort and her friend, she told me who liked whom, who was arguing with whom, what was troubling her and what made her laugh that day. I somehow comforted her, even though my words of encouragement were confined within my immovable smile and compressed figure. I made her feel as though she was at home. So when she gradually slipped away, nights that used to be our time replaced with mountains of studying or texting friends or crying, I wondered what had changed. Soon, I was dethroned from her bed and forced onto the top shelf in the farthest crook of her room, as if a figure of the past, nothing but a footnote in her long story of life. No longer did she cling to me every night, unable to sleep without me there. No longer did she tell me her stories of what happened at school that day.

No longer did she tell me her secrets, ones that she swore she told no one else. It was as if she outgrew me, like a shirt two sizes too small. I felt like an outsider looking in, rather than experiencing life with her like I did all those years ago. Gradually, like a wave ceding from the shore, I saw the childlike spark dissipate from her eyes, forced away by the claws of responsibility and stress. She’s changed, but I still hold on to the hope that she might come back for me.

–The Girl:

On the car to the possible start of my doom. The trees blend into streaks of green and the soothing rumble of the engine holds me steady, somewhat. I go through my mental checklist over and over and over, but a gnawing feeling in the back of my mind haunts me, throbbing as if for me to remember the one thing I am missing. It doesn’t come to mind. I assume it’s unimportant and try to squash the feeling of apprehension slowly trickling into my body. It must be just another old trinket collecting dust, another rogue memory scrambling to latch onto me. It must be nothing, so it’s disregarded.

–The Teddy Bear:

It’s been a few days, with specks of dust the only thing coming and going and staying. My hope is waning. Maybe she remembers and just can’t come back, maybe she doesn’t need me, never has. If that’s the case, I’ll stay here, a figment of her past with her childhood in fragmented recordings, the flashes of innocence and nostalgia simply a movie kept safe behind my untouched doors. I can afford to be left behind. I’ll hold onto these memories until I perish completely, barely a wisp of smoke, but I’m always happy I played a part, no matter how small, in the wondrous tales of her life.

By Arthur Yang, Year 11, Harrow School

Accompanying piece by Kit Henson, Year 13, Harrow School

It was on a fine sunny morning, many years ago, that a fresh pine shoot pierced the dew-stained earth to greet sunlight for the first time. The land was open with a clear river in the distance, and a small number of mud huts thatched with dried grass congregated in a little vale next to the river. The faint, blue-grey smoke rose from them as the men and women covered in deer-skin dresses prepared their breakfast. The pine tree still remembers those days of his infanthood, especially of the villagers with baskets of stern and resilient vine who passed him each morning to hunt and forage in the woods, and seeing them return, often bountiful, but sometimes frowning in the blazing-orange light with empty hands.

Many years passed, though the pine was still in his youth. He remembers one particular day, when, at dusk, a strange man with light-coloured hair, wearing leather with patterns he had never seen before, approached from the other side of the river, and waded across to the village. Since that day, the villagers began to scatter seeds in the fields around the pine tree, and every now and again would take water from the river to water them like birds regurgitating food to nurture their young. Slowly these sprouted and grew to be tall and noble, with golden grains so heavy that they bend with their own weight. Then the strange man and the villagers harvested these new-born crops. He cooked it over a fire the asked the villagers to taste it, and they were amazed. That night they lit a bonfire and danced and sang to celebrate this new discovery. The next morning the man had gone, going further east into the woods with a small bag of the harvested grains in a wrinkled leather pouch.

Many more years passed, and the fields of grains extended from the sides of the river to the edges of the woods, enveloping the pine tree completely. Now rather tall, he sees the villagers labouring in the fields daily. Hardly ever do they go to the woods and forage anymore. They often rested under his shade when the sun blazes at noon, and every harvest they would offer some grains to the pine tree, and sing and dance around it. Their numbers multiplied quickly, and they started to build houses from stone and wood from the forest rather than mud. The pine remembers, around this time, another man came from the west across the river at dusk, dressed in a kind of smooth, brown cloth he had never seen. He stayed for many months, and taught the villagers to pick out small golden pebbles from the river so that they could trade with each other for lumber and food. The villagers happily gathered these up and hoarded it in their houses.

Many more years went by, and the village became bigger and bigger, with a stone wall around it and a big stone house in the middle. More and more travellers began to come and stay, and many villagers themselves also wandered away. The pine tree remembered seeing their little shapes grow smaller and smaller until them seemed like mere pebbles by the disappearing river. One day a peculiar man arrived from across the river. Every night he gathered the villagers by the gates to tell stories, and after a few months the villagers built this little stone house outside the village, and every few days a bell would ring from within, and the villagers would all flock to it like bees and stay for hours. Some of the older men were unhappy because they stopped sacrificing to the pine tree. One of them sneaked out at night and placed a bundle of wheat by its roots. The next morning he was whipped to death and his wrinkled body was nailed to the tree’s trunk.

Then came a year of drought. The pine tree felt its leaves and twigs turn brittle and fall under the blazing blade of the sun which sliced through the ground and left deep cracks. The crops all withered and became so crisp that their stiff stems broke with the powerful winds of summer. The earth became still and void of the bustling of life. The villagers began to fight over the little food they had left. Several of them took their belongings and wandered into unknown lands. The rest sat through the remaining year withering away and many people died, and their bodies lay about unburied. When rain finally came in winter, the pine tree and the villagers drank gladly, and with the food they had left the villagers made another offering to the pine tree, and knelt there and prayed to give thanks. The also took several of their children who died that year, and bur-ied them next to the tree. The next spring little white daisies grew over their little mounds and the pine tree was pleased as he felt the newborn pulses of budding young plants.

Another many years had passed, and the village wall became taller and taller. The tree was now quite old and watched as the villagers carry on with their lives. The big stone house in the middle of the village grew in size, now with a tower taller even then the pine tree, and a magnificent roof that glittered in the light. After a few years the pine tree felt that his branches grew less ardently in spring and in autumn he bore fewer and fewer pinecones. One day he felt strange trembles from across the river, and a cloud of dust flying up in the west, which scattered the sunlight into a blood-like colour. The next day some men, riding on big, tall horses arrived. The villagers were scared of them, and hid in their houses. When these men saw the little stone house built outside the village where the villagers went and prayed, they were angry and shouted. The plundered through the village, taking the gold, and killed everyone who was there. They piled the dead bodies up in a big heap outside the gates and set fire to everything. Then two of them went into the stone house and dragged out the bronze bell, rolling it along the ground like ants with their newly hunted prize. Then, allowing it to make a final cry of despair, they smashed it with a large hammer, and it shattered to pieces. The fire burnt all night and in the morning all that was left was scorched stones walls without roofs, some crisp, black stubs of wheat still stubbornly holding onto the burnt ground, and a little dull stump in the middle of the fields. It was probably the tree’s remains.

By Aneeka Jayasimha, Grade 7, Harrow International School Bengaluru

Every day while going to school, I noticed desperate, vulnerable kids begging near traffic lights, risking their lives while weaving through the busy streets. I started to think about their stories, their lives, where had they come from?

Several hundreds of children were kidnapped and forced to walk around the streets of Yeshwanthpur, under the scorching rays of the sun, begging for money. They are victims of human trafficking. In India, cows are sold for a sum of up to ₹20,000, but children could be sold for only ₹500 – just as much as a T-shirt.

From the remote village of Chuttugunta, Aishu was one of many children, kidnapped and brought to the city. She was put in shabby tents, made of cloth and plastic, with no basic necessities. There were no less than seven kids in one tent the size of a small car.

Living with a man she knew as her father, and a woman she called ‘grandmother’, Aishu was made to beg near traffic lights and on busy streets. When she was just an infant, Aishu would be carried around by the people who were said to be her family. The passers-by felt pity and gave them money.

Years passed, and Aishu grew up. She was then left on the busy streets, forced to beg for alms on her own. The day Aishu turned 5 years old, she was given a picture of a god to hold in her hand while she asked for money. It had been four years since her abduction. She had no idea what it would be like to play in the playground with her friends, no idea what life would be like if she hadn’t been taken away from her parents. She struggles every day to stay alive. She would collect about ₹200 to ₹300 on good days. Every day she had to give her keepers a sum of ₹200, or else she was starved and beaten. Aishu would get up at 3 am, leave her tent, catch a train or bus to Magadi road or RR Nagar signal, and start her long day, roaming the streets of the bustling metropolis.

Aishu was nine when she was finally rescued. Aishu was at her tent when policemen walked in. In the eyes of Aishu, the sudden appearance of the policemen was surprising and confusing. There was too much happening and too fast for her to comprehend. She was in shock at seeing people coming in and taking away all the children inside the tent. She was taken outside and put into a car to be sent to a care home. Slowly, she realised that these people were only there to help her. She could see the urgency and sympathy evident in her rescuers’ eyes. Once she was at the rescue house, she felt a weight lift off her shoulders. She felt free.

Many children and infants were saved that day. At the house Aishu ate a healthy meal and she knew she was now safe. She was checked up by doctors and given fresh clothes. Aishu’s rescuers gave her a home in an orphanage, and she started going to a local school. She was put into lower kindergarten at age nine, though Aishu was much older than her classmates, she had no problem making friends.

The man and woman who claimed to be Aishu’s father and grandmother tried to fight in court, to bring her back to them. During that time, Aishu was hesitant to meet them. There was no evidence to prove that he was or wasn’t her father. While speaking to Aishu her rescuers asked who the man and woman were. She told them that he wasn’t her real father and that her biological parents had left her and run away when she was just a baby. She was made to believe that these people saved her, even though they treated her so awfully.

Thankfully, Aishu was safe and stayed with her rescuers. The man was put into jail, but not for long. He was released on bail. Days later, the police regretted their decision as they received four more files of missing children and three were linked to the man.

Aishu told her rescuers that there were many other kids like her, who were still out there and suffering. Aishu remembered the place where they were staying and described the place to her rescuers. At 11 pm one night, her rescuers set off to bring the other kids to safety. They went to the exact place Aishu had mentioned and found many tents. As they peered into the first tent, they realised that it was empty. They searched all the tents there but didn’t come across any children.

There was a man standing near them, his expression cautious. The police noticed him and asked if he knew about the children. Eyes filled with suspicion, he wondered whether or not to inform the police of the location of the children. The police realised he wasn’t going to give them any answers without reason, and decided to tell him why they were searching for the children. Upon realising their cause, the man immediately led them to the right tent. There, when they approached the tent, they found seven children and two women. It was evident that the man too had seen the suffering of these children and was relieved to see them rescued. Aishu’s statement had saved nine other lives.

Aishu’s rescuers had given her a new life. Her keepers could do no harm to her, she now had a safe place to stay, and enjoyed going to school and playing with her friends. She could now dance around, wearing her new dress and bangles. Aishu knows that she is one of the few fortunate children that do get to start over. She is a treasured ray of hope for a brighter tomorrow.

By Mac McDowell, Year 11, Harrow School

On Monday I received the invitation to join my aunt and uncle at their house in venerable Old Lyme, Connecticut. They invited me to stay for the long weekend; I lasted only an evening. “Hyper fixation” is a term I use to describe my ruminations about that night as a member of the extended Elliot Family. My mother was a member of this clan, and as such had done her best to keep me in the whirl of their orbit. They were rich. My father’s family, the Russian side, was not.

That they were rich, there was no mistaking, from the 19th Century manor house, the Rolls Royce kept warm in the garage, to the chalk-striped suits. Never in my life had I witnessed such prosperity as I had at the Elliots. You see, although born in St Petersburg, and burdened with the quasi-Slavic name Dimitri, I was as American as Wonder Bread, raised since the age of four in Yonkers New York by my mother. My father had abandoned us to continue his work in Russia for the state, a destiny, according to my late mother, to be “the greater of the two miseries”, the other ‘misery’ being the role of a parent. As the scramble of the fates would have it, one afternoon last month only a few days after attending my mother’s funeral, I received a letter in the mail. It detailed the contents of my late father’s will, and I smiled, not only at the news of the old bugger’s death, but also to discover three hundred dollars broken into twenties that had slunk to the bot-tom of the envelope. The next few months would be covered where rent was concerned. Seconds away from tossing the rest of the contents into the can, a small green notice slid out from the package and fluttered to the ground, marooning atop my toe. Upon retrieval, I discovered the letter was an invitation, written by my Aunt Marie (the sister of my father, and the wife of my uncle Harold), that contained references to the ‘cold Russian fronts’ woven between overwhelming condolences written in loopy handwriting, accurately likened to the oscillations on a polygraph test. It was that day, that all the nerve endings of abandonment and pover-ty rolled up and presented themselves to me in a firm cord of opportunity. Though I felt ashamed to accept an invitation to represent a man I detested for the benefit of a family with whom few memories I shared, I’d be a fool to turn it down. I took the train up to Connecticut a week after I’d received the message. I antici-pated an open-arms reception, replete with tears, and deeply sympathetic expressions, such despair I would combat with looks of feigned Russian stoicism.

Crunching across the gravel driveway to the front of the house, my path lit by moonlight, I remembered that I’d packed what I believed to be a ‘nice shirt’ in case the moment demanded it. This moment came earlier than expected and upon rounding the corner of the great Georgian façade I was greeted by the glowing first-floor windows, bright with celebration. The nearer I grew to the front doors the clearer the music be-came and the more I wished I’d stayed in Yonkers. Nevertheless, the doors parted and after a few quizzical looks and frustrated explanations, I was invited into the din myself, first taking a left into the powder room to change into appropriate dress. I can’t remember how long I stood there, facing the mirror, all senses but sight, numbed like some shell-shocked soldier; zoned out. It was a fine bathroom and certainly a far cry from the shabby toilet in my apartment. I saw in the mirror that my hand was shaking, and I wasn’t aware of it until just now. I wondered how long my hand had been shaking for. I wondered a great many things in that moment, and although I didn’t drink, I felt I needed one. The trance was broken by the bathroom door swinging open, my hand stopped its humming, and I took my cue to join the party. Floating across the wall-to-wall carpet, I entered through the doubled doors into the loud hot space and assumed my seat.

“So how do you know the Elliots?” was perhaps the most popular question that night. I repeated my mantra, trying not to sound too bored, and signalled the waiter for another fork, the old gorgon to my right had knocked my fork (and knife for that matter) clean off the table three times after continued tipsy gesticulations. Believe you me, I would ask her to politely ‘pin her wings’, but not even a foghorn could get her attention (perhaps I should have asked the waiter for an ear trumpet!). To my right was seated a great Falstaffian bore. He claimed to have been a friend of uncle Harold’s in the army, but left earlier than my uncle to “fight the good fight back at home”, a phrase which, I had a feeling, served as an euphemism for diabetes.

His rumbling tones provided the frequency for complete derealisation. Past glowing candlelight and wineflushed faces our gracious host arose like a pillar in the dark, glass and fork in hand, silencing conversations with a ring and beckoning me back to the present

“Thank you all for coming. As many of you know, dear uncle Petre passed away just last week. Appreciating full well the dangers of staging a funeral in St Petersburg, and given the current political climate, not to mention those terrible blizzards, the family decided it would be best to bring a bit of St Petersburg, back to Connecticut. I’d like us all to raise a toast to late uncle Petre, and his son and successor Dimitri, who has so wonderfully accepted our invitation, and will be spending the next few days with us here.”

I’d predicted the subject matter of the toast from a mile away and now wished more than ever to escape this party by any means necessary. Swing on the chandelier and smash through the window? Fake a stroke? Having to act as if the death of my father meant more to me than a Knicks game proved harder than anticipated. The fact was, I was surrounded by people who pitied me, I was humoured. Staying with an aunt and uncle whom I hardly knew was an exercise in awkwardness within itself but crafting a false identity and faking heartbreak all for no particular reason, impossible for a guy like me.

“Dimitri! Welcome ma ’boy, the last time I saw you, you couldn’t even walk! How’ve ya been.”

Harold’s eyes were like milky marbles, he spoke in an odd rhythm. He gave the impression of a man who lost his temper often. I asked when the last time he’d seen my father was, he said: “Not since the wedding”, ironically, the same could be said for me. As I sat there, a strange feeling nagged me. Suddenly, as my wine-drunk eyes drifted from the marble reflections of warmth to the dazzling tapestries, I wondered what divine stroke of luck had made these chosen few so fortunate. If it was merit, I had none. Shadowed nobility, an innate sense of the bigger picture, I am many things but had never once been accused of ambition. This was not my destiny, there were no hints, I had no inkling, and I couldn’t shake the feeling that something terrible would happen if I pursued my present course any further. I’d been feeling off all evening and thought perhaps this ‘guilt’ was the reason why. I entertained my host, and balanced on the high wire of interest, renewing my subscription to the conversation with a well-placed nod or two and a pleasant grunt.

When the party concluded, guests were ushered out into the driveway and Aunt Marie gave me directions to my bedroom. I waited a moment, standing alone in the front hall, weighing my next move, then I turned, ignored my directions and opened the large front door, slipping away into the cold night air.

Twenty odd minutes later, my breath was held ghost-like in the April moon and I made my way down slippery carved stone steps to the station in the dark, waiting alone until the train rambled up. I leapt aboard and assumed my seat in the otherwise empty car. I stuck my head out of the open train window and felt that damp, earthy, cool air wash over my face and sting gently my eyes. New England in the early Spring has a quiet charm to it. I didn’t use to like Spring much at all. In my mind, it was the shoulder to all seasons and felt undeclared, too warm to snow, too cold to go outside; or as my late mother called it, “misery of indecision”. I now know that A. My mother was a miserable woman, and B. Spring provides the dose of mediocrity one needs to stay humble. That night as the train rolled past moonlit pastures and distant sylvan hillocks, a salty tear welled in the corner of my eye and an absolute truth sunk into my skin; my voice whispered the word, “orphan”.

The Journey to Find the Golden Fleece

before...

Pelias’ eyes gleamed. A special kind of hatred dripped from his words, one reserved only for Jason and one only Jason could hear. “Yes. A quest to find what no other adventurer has even come close to.” The hall quieted. A breeze stirred the leaves outside and gently swept Jason’s hair.

“You will go and find me the Golden Fleece.”

That was how Jason came to stand on the newly built ship the Argo, assembled with the own hands of Argus, one of the heroes Pelias had recruited for him. Argus was just one of the heroes joining him: there was Heracles, strongest hero in the world; Zetes and Calais, sons of the North Wind; two hunters Atalanta and Arcas who were famed for their mastery of archery, and tens more —some of them already bearing a list of notable heroic deeds and others who were looking to reach the same level of fame. The rest of the heroes boarded the ship. Jason turned his eyes to the horizon and they set sail at last. Their journey started off rocky. About an hour in, a tempest struck their ship. The waves struck the hull of the Argo and threatened to capsize the ship. Fortunately, Argus’ craftsmanship held up and they were able to survive the storm without too much damage to the ship.

After the storm, however, Jason received a message. The goddess Athena had been watching over him since the start, and whispered a word of advice in his ear: Up ahead were the Symplegades, the Cyanean Rocks. These were massive rocks that were in constant motion and clashed together whenever a vessel went between them. Jason’s crew were in distress. However, Athena let them know that there was a way they could get through. Jason had to release a dove through the gap between the rocks. If the dove got through in one piece, so would the Argo. Their ship slowed down, and Jason nodded to Argus, who climbed up to the helm and braced one foot on the side of the boat. In his hands was a mass of fluttering white feathers, bunches of claws that formed a scaly cage, beating against his fingers, and a tiny heartbeat that drummed out a nervous tattoo, almost matching the pulse at Argus’ wrist. The crew watched silently. Argus opened his hands to the sky– and the bird took flight.

The dove flew in a straight line right to the Symplegades; with all the precision and exactitude of an arrow, if not speed. The rocks rumbled and drew slowly apart. The dove quickened and Jason swore he could hear the whistling of the wind between its wings. The rocks rumbled again. Tremors shuddered through Jason’s bones. The dove’s wings gave one last frantic beat. The rocks smashed back together. As the dust cleared, the crew of the Argo waited together in bated breath. The rocks drew back, and something fell to the sea between them: a single white feather, clean and spotless and free of blood. The dove had made it to the other side.The crew drew heavy breaths back into their lungs. But the rest of their journey had yet to come.

The island of Colchis was a paradise of gold sand that shone white in the sun with sunsets that blazed across the whole sky and left the crew blinded in their morganite glory. Its very soil sang with the assurance of wealth and prosperity; it was even said that King Aeetes took every bath in a tub of solid gold. Jason felt bolstered by the knowledge that all this was caused by the presence of the Golden Fleece.

I love to play the poet: pen in hand and omni everything, designer of tiny people imago Me, direction: run around in your respective little homes, I build them of flowery metaphors, caesura, a high regard for places personified as sycophants at My every command.

words are My favourite form of sustenance: I scoop up letters one by one, chew them through, form the syllables, bite-sized, bitter on My tongue, the refrain for breakfast, please, and a tart volta for tea— save the rest for later, supplements of well-meant dissent, the word intent represents My built-in poet’s choice of language, syntax, a search for similar synonyms: redundant, My verse without rhythm or rhyme.

but construction is more delicate than you think: I approach carefully when context calls for it, garnish with the easy-to-omit allusions: not literary but personal, it’s embarrassing to admit, I (of course) know, but here goes: sometimes the poem is me, mortal mere and drear, yes, the blood spilling onto pale page— my deifying myself with words.

and so I and i, poet and poem, finally arrive at the last line, through oxymorons, allow myself to be both permanent and impermanent, creator and creation, a ceaseless existence as my paradox of poet and poem, ever subservient to the careful craft.

In this world of hatred, A writer sits with a pen and paper. She sees heavily defined, invisible lines, scorched imagined borders.

Identities’ depth reduced, sealed quiet.

With the frustrating silence, She leans towards the suppression and succumbs as messages, born from the depths of her soul, spark in the corner. It spreads across the folds of terrain.

in her grief: She writes in the blood of her late father, spilled onto hands which swore to protect as she writes to commemorate the names of her ancestors replaced by slurs - names that break bones and laws so ugly that she must write to save the revelation of unborn babies when they fight against hatred unfaulted of their own.

Identities come alive, narratives collide, a voice to the voiceless as a chorus coincides to fill the world with unmistakable truth, vivid landscapes of truth.

In this world of hatred, A writer sits with a pen and paper. With fire she builds, she watchesAs its power creates a gust of wind propelling itself forward She burns the books She burns the scorched lines Down in history.

By Nara Chenyavanij, Year 9, Harrow Bangkok

As death pulls me in like a string, The radiant glow in my heart is now gradually diminishing. I close my eyes. And I see me. I see my journey.

The world was scribbles It was shapes, colours It was full of the unknown And that was okay.

Her bubble of bliss was that of her own, As she paints and draws stories untold Her eyes were blinded, full of art. The golden light. It marked her heart.

Crayon in hand, The young one draws Outside the lines of her colouring pages She built worlds and legends with her stubby bare hands.

Oh young one, what I would give to relive it all. For the world is still unknown But the answer was still out of reach.

By Anushka Ganesh, Grade 7, Harrow International School Bengaluru

Do I want to win this battle? It was a fight to wake up before the first rays of light. Three families in three different tent houses in Barsu. I never found out who woke up first, but it was not me. We all gathered in the dining hall to find ourselves eating the same thing for breakfast. It had been three days straight that we had been eating aloo paratha for breakfast and maybe lunch and dinner too. People in Uttarakhand usually eat foods like aloo paratha and roti as they increase the amount of energy which the body can use to generate heat in the freezing cold. Soon we packed our bags and got into the Tempo Traveler. It was about 9 o’clock when we left Barsu, it was a long ride to Gangotri and half of the people on the bus were motion sick. Motion sickness was a natural disaster inside our bodies which we had to face individually; we could not escape it without medication. The treacherous bus ride gave us a chance to mentally prepare for the treacherous hike.

We arrived at Gangotri at about 10:30 am, waved goodbye to the comfort of the Tempo Traveler and walked towards the Gangotri National Park. Right before we reached the entrance, we saw a mule shed where people were offering a ride to Bhojbasa (the place where we would stay that night). We needed to decide who would go on the mules and who would walk. I felt it was most important to be healthy and not dead by the end of the day, so I chose a mule. Some people chose to walk, so if they were about to faint, it was the consequence of their own actions. At the same time, they were all at least saving money, unlike the people riding the mules (including me).

One bhaiya (the person who took care of the mules) had two mules, which meant that the bhaiya would only lead one of the mules and the other would walk on its own (maybe because it was smarter than the other mule). At first, until we reached the park, I was riding the mule which walked on its own, but right after we reached the park, I swapped mules with my mom because it was too scary riding the solo mule. Plus, I needed someone to talk to which was obviously the bhaiya. Soon the forest officials checked our permits and we all started walking or riding in hopes of reaching the destination safely.

Slowly I could see that the people who were walking behind us were fading away into dust, and I could see the mountains dominating the land. The best part of this hike was that there were not a lot of touristy people around. When I say touristy people, I mean the people who take a lot of unnecessary pictures and the irritating ones who scream for no reason.

Even if you were walking alone, you would still have one thing accompanying you till the very end, and that one thing is the river Ganges. The river will never let you lose your way and guides you along the right path, but you do not want to get too close to the river (and drown). The mountains were gradually enclosing us. I could see the mountains everywhere.

I asked Bhaiya “Bhojbasa pahunchane mein hamen kitana samay lagega?” which meant “How long will it take us to reach Bhojbasa?”

Bhaiya replied with “Abhee bhee bahut door hai, hamane abhee shuruaat kee hai”, which meant: “Still a long way, we just started!”

In my head I thought, What does he mean we just started? It has already been about 2 hours! I was terribly angry, but soon the mountains and the river Ganges calmed me down. I started chatting with bhaiya and I learned that ‘Jyothi’ was the name of the mule I was sitting on and ‘Dheera’ was the name of the mule my mom was sitting on. I never knew that mules could have names, but this bhaiya loved his mules a lot and that is why he decided to name them. Soon another hour passed, and I had spent 3 hours sitting on Jyothi. My back became stiff and I could barely move.

I heard something like footsteps, but louder. I thought those footsteps were made by people, but those sounds were made by other mules! This path that we were on was only big enough for one mule and one person to pass through. But when it came to two mules passing by it was a hairy time. The other mules were at a spot waiting for us to pass. Bhaiya left me and Jyothi, and he went with Dheera and my mom, so they could pass safely. But right then the other mules started rushing towards us, the mules came so close that I thought they were going to bite my leg off, and I screamed “BHAIYA!” The bhaiya came running and saved me from the crazy mules.

Fifteen minutes passed by; I was just cooling myself down from my brush with death when we found ourselves having to cross the colossal river on the mules! I told bhaiya “Aap mere saath hee aajao,” which meant “Bhaiya please come with me.”

In my head I thought, What does he mean we just started? It has already been about 2 hours! I was terribly angry, but soon the mountains and the river Ganges calmed me down. I started chatting with bhaiya and I learned that ‘Jyothi’ was the name of the mule I was sitting on and ‘Dheera’ was the name of the mule my mom was sitting on. I never knew that mules could have names, but this bhaiya loved his mules a lot and that is why he decided to name them. Soon another hour passed, and I had spent 3 hours sitting on Jyothi. My back became stiff and I could barely move.

I heard something like footsteps, but louder. I thought those footsteps were made by people, but those sounds were made by other mules! This path that we were on was only big enough for one mule and one person to pass through. But when it came to two mules passing by it was a hairy time. The other mules were at a spot waiting for us to pass. Bhaiya left me and Jyothi, and he went with Dheera and my mom, so they could pass safely. But right then the other mules started rushing towards us, the mules came so close that I thought they were going to bite my leg off, and I screamed “BHAIYA!” The bhaiya came running and saved me from the crazy mules.

Fifteen minutes passed by; I was just cooling myself down from my brush with death when we found ourselves having to cross the colossal river on the mules! I told bhaiya “Aap mere saath hee aajao,” which meant “Bhaiya please come with me.”

Bhaiya replied with “Nahi, app Jyothi kesaath aajao” – “No, you go with Jyothi.” The bhaiya could not come because the river was too deep. I was holding on for dear life!

After a while, I heard loud footsteps, Oh no the other mules are back! I thought, but this time I did not see any mules. I looked up and I saw a family of Himalayan blue sheep.

I yelled out to my mom “Amma! Look up!” but she could not hear me over the rushing sounds of the river Ganges.

I asked Bhaiya “Bhaiya Bhojbasa jaane mein abhee kitana samay lagega?” which meant “Bhaiya how long it is going to take us to reach Bhojbasa”. Bhaiya did not reply, maybe because I had repeated the same question every minute. I started to sing little songs in my head so that it felt like time would pass by quickly. Soon we came across a small town, and I realized it was Bhojbasa. We got off the mules, thanked the bhaiyas and we asked them to come back here to the same place at the same time since we loved the mules we were riding and did not want to sit on any other mule. We walked down to Bhojbasa and went to the dormitory. It was a bit uncomfortable to stay in a room with strangers but at least that was better than sleeping in a tent outside in the cold.

The people who came early (on the mules) took a quick nap and by the time we all woke up, it was 7:30 pm and by then all the people who walked had reached Bhojbasa. They were all tired and pale.

It was 5 in the morning when we woke up, we all got ready and packed our daypacks for the hike. After just 5 minutes passed on our hike we stopped at a huge river. We had to cross it on a trolley which was tied to two ends on the mountains. Only 3 people could get in and the others had to pull the ropes so that the people in the trolley would reach the other side of the mountain. It felt like you could fall into the river anytime and die when you were sitting inside the trolley! By the time all the people we knew reached the other side of the mountain 30 minutes had passed by, my dad put a lot of work into pushing and pulling the trolley and at a point, he was the only one doing it.

Once we had all crossed, we started walking again. The mountains were getting closer and closer. Three hours passed by whilst I was chatting with my mom and we finally reached Gaumukh, the mighty glacier. My parents and I sat in front of the glacier and observed the majesty for a long while. I picked up a pebble from right in front of the glacier, a souvenir! That glacier was the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.

By Jonathan Song, Year 11, Harrow School

The walls lie a dulled grey, seeing untold story after untold story, stories of beginnings and the endings of stories. If they could speak – they wouldn’t. Light paints a boy on the window, and he looks at me. The clock says 6:38. Sunrise. The sun is rising. From afar, roads of light build a glorious halo that erases the boy from my view. Beeping fills the room.

The door gently creaks open, and shaking, he walks in. Right on time, every day, always.

For once, he stares at my eyes, and speaks.

“You, you came to me. You said that we would correct the injustices, the sins, the world. I trusted you, I dreamt for you, I fought for you, and I would have died for you.” Clenching his fists, his façade of calmness dissolves, as tears, words flow.

“There comes a time where inaction is betrayal, and you crossed that line four years ago. For fuck’s sake, pull yourself together” He grabs my collar.

“Being here, in this place – this hospital, doesn’t mean you can’t write like you used to, think - like you used to. You gave up on us.” His rough breathing echoes between us.

How large the sky’s heart must be, for it to be able to envelop the world? How foolish must man be, to build shields against nature’s eye?

He notices the thoughts of mine wander. They seem to do that a lot nowadays.

“So be it.”

He left some of my old works on the desk, must have forgotten to take them with him. The books make their way to my lap, and the record of my thoughts flows through me.

Years ago, I sat atop a wooden throne in a wooden palace, and I lit the match, I burnt it down. When I sat on that throne, there was a mirror in front of me, and I could see a fluorescent halo behind me. The whispers of the paths of light were my gospel, words from my god, words from me. – From ‘Perspective of a King.’

Was I also always chasing after myself? Running from demons of my own creation? A true halo doesn’t enlighten, it burns and conquers.

At some point, men stopped worshipping nature, but explained it. Men created machines to move nature, and then man began to worship machines, not nature. – From ‘A Call to Action’

Beeping is sent in quicker and quicker pulses across the room.

In a plea to stop my past’s attack, I bid the grey walls to speak to me, yet they awaken not. Outside, a scene calls to me. The beautiful, sprawling, network of branches, splotches of green and brown, with delicately sculpted ivory flowers. Below, an area unreached by the roads of light, hides the scramble, the tears and blood of thousands of failed seedlings. Still, the fight continues, as the giant encumbers all under him. Like He does. Ugly, powerful, brutes may fall, but how many like David had to fall before? How many like me? And who chooses the winner? In my past, I found the word ‘Amen’ comforting. It meant ‘so be it’, as if it was pre-written that I, with God’s love, would stay standing.

Now, it means acceptance. Like pigeons living in concrete forests, like a priest in a gambler’s den, like the people who ignore the graves atop which the current order of things is built, I accept my loss.

The pavement outside, once gilded with cobblestone, used to grow radiant pillars of fire at night. Weathered by scars, it now holds naught but a flickering glow and produces a decrepit buzz. The only record of the journeys people take is this – the damage they cause. Is the world still ‘very good’? Perhaps, like me, his last creation was his worst mistake.

I once thought the stars were just another step away. I now know, no matter I build myself up, a being made of earth can never reach them. He must have spent the most time on composing the infinite symphony of starlight, for their performance shall propagate its divine music eternally, a music my cacophony could never match.

Do I want the one left standing to wash off my blood so easily?

Is this another obstacle, or the obstacle?

The horizon’s lump of coal’s incandescent light is quelled, yet it releases blood-soaked roads of light as a final resistance to the coming of the night. Yet, as was weaved in the threads of fate, as happens every-day, the sky is buried in blue darkness. All paths are blocked now. But still, I stare, craving for the sight of any more rays of light.

So be it. No hint of the halo can remain. Truly, no being can escape fate. One can never step off the hedonic treadmill.

***

In the scars, I see the smallest spot of green. The sprout staggers feebly, like a soldier after a war, as dew brushes across it. The morning dew holds in it the memories of the world, and the paths of light that dare to enter the dew are distorted. Yet, still it stands, a victorious stand.

A lone ant saunters over, its steps ringing in no-one’s ears. Death has loomed over its shoulders all its life, and the ant greets him every morning, saying ‘So be it’. The ant welcomes the final rest, accepting it and using it and holding it with glee, for the benefit of its people, for the birth and development of something new and bigger than itself.

It holds the dew in its mandibles, and glares, issuing a challenge, to all those who walk by. None dare accept, or perhaps none notice.

Could I also have? Should I also have? Can I accept and fight, after all this time?

I wish the unsleeping city would sleep today, or the unspeaking walls speak. As the beeping slows, I yearn for the Moon, yet it hides from my scrutiny. The solace I could have found in its unapproachable, unchangeable allure is nowhere to be found.

Slumping, I recall the most comforting words of my life.

He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.

‘Amen.’

By Kawisara (Venice) Prapaipichit Year 10, Harrow Bangkok

Do all women dream of being girls again, in the same way wolves dream of being dogs? In the way that they yearn to return to innocence, and wish they didn’t have to become so vicious.

Do they ever spare glances behind them at the havoc they have wreaked during their journey? Gravel path stained with blood; fur and hair shed and forgotten; broken nails and claws haphazardly strewn about as reminders of their animalistic struggle, their fierce grapple to survival in an unkind world. Do they look back and mourn?

If they stare at the path for too long, does it swim in their vision as a prelude to a trip down memory lane?

The gravel morphs into the river your brother pushed you into when you were kids, for the simple crime of thinking you had the right to try and play pirates with them. “Women on ships are bad luck,” they taunted, and, “She’s a siren trying to trick you, get back!”

You are whisked back into that moment, now. Jarringly. Suddenly. The suffocating humiliation of being made to ‘walk the plank’ chokes you just as viciously as it did a decade ago. How did other girls cope, being punished for the simple crime of being born?

Stumbling, you let them shove you into the water. They laugh cruelly when they see the tears well up in your eyes and you imagine picking up one of the rocks in the river and throwing it at them. Is this how it startedthe innate blood thirst that seemed to be built into your very core?

Their sneers and sniggers encircle you and you shrink further into yourself. You’d rather take apart your own rib and drive it into your chest if you had to live the rest of your life tormented by boys like this.

For all their repulsion of girls, however, they also seemed rather disgusted by some boys, as well.

The river changes into a winding hopscotch pattern. You are at school and it’s his break time and all the students were released into the courtyard all at once like a title wave of faces you were certain were laughing at you. Hours you have spent staring at this pattern of squares, too anxious to look up.

It is colourful. That has always stood out to you. Pink, blue, purple squares with green and yellow numbers –and then, an alarming blotch of red because your brother and his friends just pushed over a boy. He looks around your age: nine years old. Young enough to feel helpless at the assault, but old enough to have anticipated it as a punishment for his difference.

Blood spills from his left temple in scarlet rivulets. Coursing, it fills the gaps in the tiny stones, like lava winding down a volcano, pulsing hot and almost unbearable to look at. You want to mop it up (‘girls are supposed to clean up’, right?), bandage his face (but not heal it - ‘girls are nurses, not doctors’), yet all you do is sit there, a toy horse clutched in your iron-wrought grip (‘girls always get squeamish at the sight of blood’, don’t they?).

The only thing that snaps you out of it is your brother’s spiteful voice. He is at the forefront of his army. Yelling about how the boy is a freak, and other words beginning with ‘f’ that make you flinch, feeling the disgust in his tone despite how oblivious you are to their hateful meaning. Scrambling backwards, desperate to escape the coming onslaught, he shoots you a pleading look. For a second you feel connected to that boy, like there is an invisible piece of string between you - or perhaps a rope fashioning itself into a noose.

You are frozen in place. You wish you could escape this moment, but you can’t, so the next best thing is to ignore it. Your eyes travel back to the familiar squares of the hopscotch path, and you let it suck you into another reminiscence.

You are frozen in place. You wish you could escape this moment, but you can’t, so the next best thing is to ignore it. Your eyes travel back to the familiar squares of the hopscotch path, and you let it suck you into another reminiscence.

The path morphs once more. It gains texture and years of laughter. It is the crow’s feet at the corners of your mother’s eyes, the ones she is currently icing with determined - no, desperate - strokes.

As all daughters do, you thought your mother was enchanting, and regarded her with a reverential kind of worship. Like a silent prayer, or perhaps one that transcended words, you sat on the floor next to her chair and gazed at her, wondering if Aphrodite was also unaware of her own beauty - and most importantly how you could make her realise it.

“You’re so pretty, ma,” you remember whispering, because something violent writhed in you at letting her believe otherwise. She was your mother, and you had her eyes. She was your mother, and you had the same sincere smile. She was your mother, and you were made in her image. Meaning that you were only as beautiful as she let herself believe she was. Unable to comprehend how she could ever hate proof of her joy, you remained fixated on the features she was trying to change.

The crinkled lines along your mother’s eyes transform once more, this time into golden strands of hair, spilled across your pillow.

You trace them back to the girl laying down next to you, who has an affinity for poetry and hates going home to an empty house after school, so she comes to yours instead. She is giving an impassioned speech about how important poetry is, and you listen attentively and watch her lips. You think you can somewhat relate: she says poetry comes from all the cracks in your soul where you have been broken, and it waterfalls out in rainbow rivulets. If this is true then you suppose both of you are poets by birthright, because both of you were told you were born inherently wrong; you were missing something, an inhibition that was supposed to prevent girls from glancing at each other too long and dreaming together too wistfully.

You thought it was beautiful, how you and her revolutionised your love, if only in the imaginary worlds you weaved for alternate versions of yourselves. However, you suppose that has always been your problem: you see a tragic, grotesque beauty in everything but find meaning in nothing, and you think this is the punishment they said you’d receive for daring to love her even for a moment. Because when the sunlight burns your eyes just right, or you see a lamplight flicker so violently you fear it might explode, you are reminded of her divinity and the way it would envelop you when you were finally able to embrace away from prying eyes.

Some days your body becomes a graveyard and each organ - heart, lung, stomach - becomes headstones for the ghosts of all the girls you have ever been and ever will be. You see her and her and them, crying in the corner, laughing on the phone, and giggling over a book she will sob over later. You wished you could’vne saved them, but maybe they were meant to die.

The gravel path only takes, and you wonder if any wolf who has walked across it still has remnants of the girl she used to be somewhere inside of her.

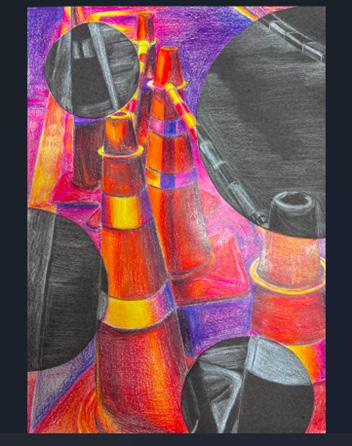

Artwork by Poonyisa (Prim) Suiwatana, Year 12, Harrow Bangkok

Streaked in capitalised faces,

The bitumen in track roads burn in fuel.

Near to the roar and revving of chastity

Came a fastidious fame and left hastily.

Formula one engines burning against each other, Head to head, Tail to tail yet

The railing race never seems to ail.

Yet, the uproar condenses in and around

The racers, distilling their breath and Their collars clutching their necks

Sometimes

It ends in a wreck.

Or more so, continued resurrection.

So back on the tracks, engines rev and rack, Some even have a knack:

Extra coin, dextrous voices, boujee oils

And earn a stack.

See, there is no surprise that they come back. The engines corrode in air itself

And air itself distils choking mechanisms to reclaim The sun as it melts with the choking lunes for centuries.

We race to condemn our history, Jeopardise

Revel in treasury

In our mysteries,

And perhaps the race

Keeps its case.

Because the human race creates, wakes and takes

The two faced, the misplaced, the Rates and the greats

For what is made awaits, and perhaps there is nothing left on the tracks, the dreary sidelines and the facts, nor the revered Finish line-

After all, it is just an imaginary line.

So the human race

Continues and races by.

I make my annual pilgrimage to the foreign land where I belong. Ice clinks against the glass cups, and waiters and waitresses jovially rush about, shouting orders over the roars of teasing and banter in the mother tongue I can't understand, and, all the while, I start to feel more and more like the imposter I am.

Someone barks at me to sit at the corner table where two others lounge. Both of them are speaking in perfect Cantonese—my mother tongue. My mother tongue I can’t understand. They are, I assume, construction workers, as they are sporting neon vests and two helmets the colour of ripe tangerines are strewn beside them. Even with the bright colours, they fit right in with the crowd of clamouring cha chaan teng goers. I am wearing my favourite black T-shirt paired with unassuming jeans; yet, when I silently lower myself into my seat beside them, their beady eyes swivel on me, instinctively sensing that I do not belong. I straighten my back in retaliation, but my trembling hands under the table give me away.

My eyes hastily dart around to see what all the locals are feasting on. I will eat the same things: barley water and an egg tart. I recite my order under my breath a couple hundred times to prepare myself.

I have to remind myself that I, too, am a local.

I wave a server over. My hand, still trembling, can be seen by all. My mouth strains at the foreign shapes it has to make, and I pray that all the intonations are executed well enough for me to be understood. Before I can even finish regurgitating the first item of my order, the waitress cuts me off, not unkindly, and gestures for me to point at the menu instead. I have to remind myself that I, too, am a local.

A few minutes later, a murky brown drink with pallid, limp grains that have sunk all the way to the bottom of the scratched cup is dumped in front of me. I eye the barley water for a few moments, and it seems to eye me back. Hesitantly, I take a big gulp, determined to make myself like it, but my throat constricts as if it is defending me against an intruder, attempting to resist the onslaught of cold that keeps flooding in, and I inevitably end up spitting the drink out

Artwork by Patteera (Fir) Lawtiantong

Year 11, Harrow Bangkok

The bitter taste of the barley water still spoils my mouth, and the egg tart never arrives.

I decide to leave the homeland where I don’t belong. I decide to leave it all behind.

by Nita Charoensuthammas, Year 6, Harrow Bangkok

Artwork by Pornpavee (Mint) Saipornchai, Year 13, Harrow Bangkok

There once was a boy, both clever and playful, a mother’s dream child. Andrew Jerkins, he was named, the boy with big dreams. He longed to sail the world, but unfortunately, he knew he couldn’t. The Jerkins’ family were extremely poor. Andrew thought that if he sailed the world, he would become famous! And what would happen after he became famous? Would he get rich? Would he go to an interview? Would he meet the queen? Whatever the case was, Andrew had foreseen a positive outcome with this dream. He knew his family deserved a better life. If only he had money! His parents and neighbours were in financial competition but neither had any luck. They were struggling to supply food so Andrew was awfully skinny! He often refused dinner as he didn’t want to waste anything. He never did homework, only spending his time daydreaming. Yet he didn’t have to worry about getting in trouble as his parents were never home. His dad was a fisherman, and his mum, a house maid to other wealthy houses. Both jobs were very low paid and definitely not enough for them, which was harsh because their jobs were very traumatising. Even though they knew it would make no difference, the Jerkins put in all their effort so they always collapsed after work. They didn’t have an option because they had very little money, or no money at all if they didn’t have a job.

His house was an old two-story wooden house that was almost a ruin. His room was a deathly, dusty menace that made the house impossible to breathe. Every room was stacked with bits of fishing equipment. Poor Andrew was left alone in the house, learning from just a few books and maps. Maps! Andrew thought, that’s right! I will sail around the world using these maps! He got up and began to build his boat. He knew it must be a secret, or his parents would explode in rage. He built his boat, nails, and wood deserted the floor. He would hide it in his room. Five hard-working days, and his masterpiece was complete…

He dragged his boat, complete with oars, down to the soothing but smelly lake in front of his house. Without hesitating, he hurled the heavy boat into the green water followed by his belongings. Then hoisted himself over the short barrier, and into his boat. It wasn’t long before dusk when he reached the mouth of the lake. His sore arms still sailing, his tired eyes were bloodshot from struggling to read. All around him, the wa-ter was turning blue. He was nearing the vast expanse of the ocean. He was getting hungry, but he didn’t want to run out of food quickly. He sailed through the night, until he smelled the ocean breeze. The twinkling stars guided him around a loop as it was too dark to read. He tried to fight the urge to sleep, but eventually gave in. The relaxing sound of the waves lured him into a trance, and before he knew it, he was asleep. His stomach was thunder inside him. He knew full well that he couldn’t cope anymore, so he took a nibble of his carrot and instantly felt much better. Light was shining through the translucent clouds in beautiful rays, morning had arrived. Lush, nature giants were towering over him, standing tall and proud. It was an island. It was spookily silent, except for the gentle rippling of waves. If anything happened, he knew no-one would know. Or bother. He rubbed his sleepy eyes. Andrew bathed in full sunlight, unsure about his decision to leave. He terribly missed his house and family. The old, wooden house was an eternal haven to him. At least until now. Guilty memories flooded into him but there was no turning back now. He’d either sail the world or die trying. Blood before death. The more he thought about it, the more agonizingly painful the memories became, so he pushed aside his worries, and bit his tongue in time. Before the tears came.

It was vast. The line of the horizon was full ahead and he was lost. He didn’t even know which direction he came from, only the sapphire landscape, which seemed to never end. Pitter Patter. He tilted his ears to the familiar sound. Eyes curious, he waited patiently for more sound. Pitter Patter. He listened until there wasn’t a patter left at all. Raindrops. Heavily throwing itself into the ocean, like a child on a springboard. Suddenly, thunderheads boomed from above and rain came pouring down. Lightning struck the earth. It was merciless.

The grayish clouds banished the sun from the heavens. It was a raging moment of fury and heat. The water, which, at first, seemed to be calm and rippling, became another place it was a minute ago. Tripling tides tried to pull the boat under with a tremendous amount of force. Andrew yelped. His boat was just above a whirlpool that was about to swallow him whole. He never had such an experience. Poseidon was not done yet…Water churned around him, making his boat wobble and tilt. The water foamed and bubbled, hissing, and fizzling all around him. He desperately grabbed his oar, but it broke as the water was impossible to steer or even control. What could he do now? Without thinking, he reached his hands in, desperate to gain control, but he lost balance and his boat toppled over and so did he. “My food!” He screamed, thrashing helplessly but his voice was cut short as he was violently pulled under the surface. He was swinging his arms wildly, bubbling.

He was resting on the shore, clothes damp, tired eyes swelled, not a single brain cell working. His blurry eyes insisted he continue resting but his brain refused. He was having a tough argument inside but only led him to a severe headache. Choking saltwater from his mouth continuing into a suffocating series of hacks. He was hugging his belongings. His boat he made was shredded like paper. He looked about. A ship was heading his way. He flailed his arms as high as he could, which wasn’t that high as he has short arms. Grunting in annoyance, he climbed a tree before waving and shouting. The ship came for him, and a man with a business coat gave him a hand. After he told the man his story, they agreed to take him home. It was a short journey. He immediately ran to hug his parents who were shedding tears on the dock. “We thought you were dead!” Mother cried.