67 minute read

DEFINING VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

from Dissertation Report

by Harsh Shah

2. DEFINING VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

The phrase ‘vernacular architecture’ is seen here as referring to the buildings of and by the people.

Advertisement

The Latin word ‘vernaculus’ means

native, domestic, indigenous. Architecture is vernacular when it exhibits all of its

criteria related to the ‘native context’ in the sense that it can only be acceptable and recognisable within any particular society by applying some particular technology, materials, social rules and systems.

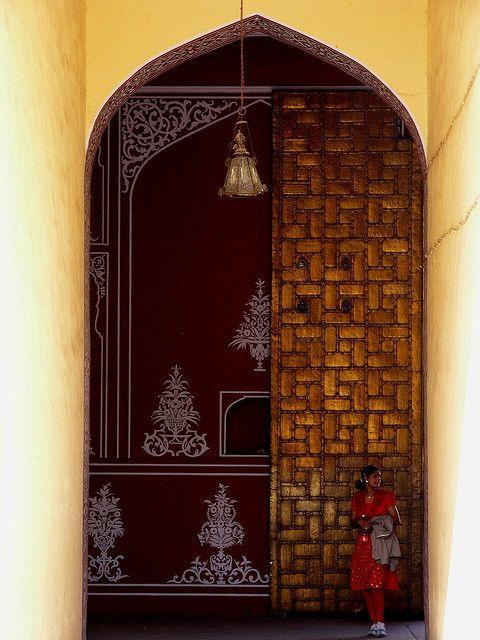

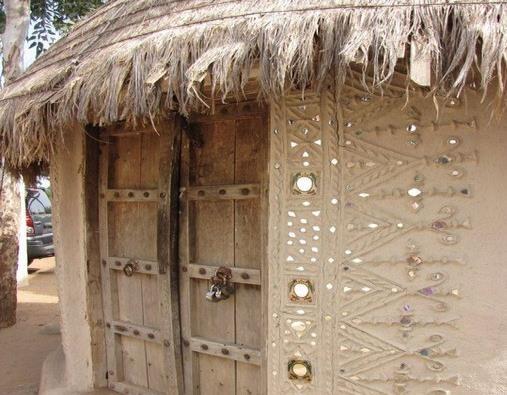

Figure 1

‘Vernacular architecture comprises the dwellings and all other buildings of the people. Related to their environmental contexts and available resources, they are customarily owner or community-built, utilising traditional technologies. All forms of vernacular architecture are built to meet specific needs, accommodating values, economies and ways of living of the cultures that produces them’ (Oliver, 1997).

It is the architecture of a place and people. It is contextual and unconscious kind of architecture. It ismore a process than a product. It involves adaptation criteria in vernacular architecture. It involves adaptationto lifestyle changes along with cultural concepts.Vernaculararchitecture is a category of architecture based on local needs, construction materials and reflecting local traditions. It tends to evolve over time to reflect the environmental, cultural, technological, economic, and historical context in which it exists.

The most commonly understood meaning of vernacular architecture, is that which has been built by the owners and the occupiers, or by the community itself based on local wisdom and traditional knowledge of the generations, using locally available building materials. It is generally inexpensive and is designed in response to the climate and the socio-cultural communities it

houses. This kind of architecture includes

dwellings, public spaces, and settlements as a whole.

‘Vernacular architecture is often referred to as “Architecture without architects” to include structures made by empirical builders without the intervention of professional architects and without the use of industrial components’, Rudofsky 1987.

Vernacular architecture is severely utilitarian in its use of materials and technology; functional in its adaptation to the climate; accommodation of activities; and utilization of site and its sculptural expressions of mass and volume. Vernacular architecture is a broad, grassroots concept which encompasses fields of architectural study including aboriginal, indigenous, ancestral, rural, and ethnic architecture.

Vernacular architecture may be defined as culmination of a creative process of interpretation of building traditions, skills, and experience, which is strongly influenced by factors such as environmental conditions, material resources, social structures, belief systems, behavioral patterns, cultural practices and economic conditions of the area.

Frank Lloyd Wright described vernacular architecture as "Folk building growing in response to actual needs, fitted into environment by people who knew no better than to fit them with native feeling".

According to Brunskill (2000), vernacular architecture has been seen as one of the ways in which the regional and the national character survived the various political amalgamations which make up the present nation. Since 1960s, efforts have largely been concentrated on identification and documentation of this genre of heritage.

These varieties of architectural expression, in the forms and structure of the entire settlements, have been a source of inspiration of architects such as Renzo Piano, Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier. Even, Hasan Fathy was a pioneer in understanding the importance of vernacular building skills and traditions and was among the first to innovate building technology using the experience of the past.

Other architects such as Louis Kahn, Laurie Baker, B V Doshi, Charles Correa, and Raj Rewal also demonstrate the re-interpretation of principles of vernacular traditions in their designs for contemporary buildings.

The next generation of architects such as Anupama Kundoo, Sanjay Prakash, Shirish Beri, Anil Laul, and Revathi and Vasant Kamath have demonstrated how ecologically sensitive and cost-effective buildings can be designed using local materials and technology.

According to Le Corbusier, his experiences made him realise the role of history in the architectural expression of a culture. History, he recognised was the palette of the architect – the wealth of materials, colours, textures, forms and other choices from which works of lasting beauty are created.

Vernacular architecture is an indigenous building style method using local materials and traditional methods of construction and ornamentation, usually "architecture without architects". Vernacular architecture is a very open and comprehensive area of architecture. It includes primitive, traditional, indigenous, ancestral, folk architecture, etc, the so called ‘Architecture without Architects’. It is the

simplest form of addressing human needs. It embraces Figure 2 regionalism and cultural building traditions and the structures have been proven to be energy efficient as well as sustainable. These low tech methods are perfectly adapted to its locale.It is a pure reaction to an individual person’s or society’s building needs, and has allowed man, even before the architect, to construct shelter according to his circumstance. If anything is to be taken from vernacular architecture, it provides a vital connection between humans and the environment. It re-establishes us in our particular part of the world and forces us to think in terms of pure survival – architecture before the architect. These structures present a climate-responsive approach to dwelling and are natural and resource conscious solutions to a regional housing need. The benefits of vernacular architecture have been realized throughout the large part of history, diminished during the modern era, and are now making a return among green architecture and architects. In order to progress in the future of architecture and sustainable building, we must first gain knowledge of the past and employ these strategies as a well-balanced, methodical whole to achieve optimum energy efficiency.

“To be modern is not a fashion. It is a state. It is necessary to understand history, and he who understands history knows how to find continuity between that which was, that which is, and that which will be” – Le Corbusier, on the definition of ‘modern’.

The humanistic desire to be culturally connected to ones surroundings is reflected in a harmonious architecture, a typology which can be identified with a specific region. This sociologic facet of architecture is present in a material, a colour scheme, an architectural genre, a spatial language or form that carries through the urban framework. The way human settlements are structured in modernity has been vastly unsystematic; current architecture exists on a singular basis, unfocused on the connectivity of a community as a whole.

Vernacular architecture adheres to basic green architectural principles of energy efficiency and utilizing materials and resources in close proximity to the site. These structures capitalize on the native knowledge of how buildings can be effectively designed as well as how to take advantage of local materials and resources.

A vernacular design has a language that can be, like any language, broken into parts and reassembled to create new meanings. When architects design in a vernacular style, they break that local design language into its components and reassemble them to write a new design story.

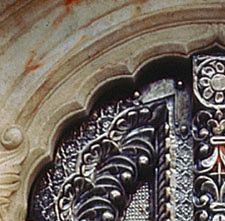

Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 6 Figure 7 Figure 8

3. UNDERSTANDING THE VERNACULAR

In a world faced with environmental crisis, climate change, globalisation, mass migration, provision of urban housing and technological developments, what will be the future of the vernacular? By virtue of its definition, vernacular may be termed as something native and unique to a specific place, created without the help of some imported components and processes, and possibly built by the individuals who occupied the particular place (Al Sayyad 2006). In the twenty first century, as the world slowly becomes a global village, and tradition and culture lose their local distinctiveness, many questions arise over the existence of vernacular architecture: will it simply disappear or will it adapt itself to the changing ecological and cultural environment? Will it be eradicated and replaced with more modern buildings or will we be able to catch a glimpse of such architecture only in museums?

The need of the hour is to ascertain whether the vernacular can be used as a

model for sustainable development, combining valuable lessons from the past with equally valuable modern technology to solve the problems of the twenty first century. Vernacular architecture continues to be associated to the past and is often stigmatized as an image of poverty and backwardness; it is conveniently replaced with the want of more progressive modern buildings.

Today, more importantly than static preservation of vernacular architecture is understanding the building traditions, knowledge systems and skills that have continuously evolved to the changing environment and yet have remained distinctive to a specific place.(Oliver 2003)

The dynamic nature of vernacular architecture of the vernacular traditions allows it to constantly evolve and adapt to its changing socio-cultural environment. These traditions are inherently sustainable in nature and hold valuable lessons that may be applied into contemporary architectural practice. The study of architecture over the

last twenty years has been concentrated on the static built forms and further research is necessary to understand how relevant aspects from the past can be transmitted into the future.

Vernacular buildings across the globe provide instructive examples of sustainable solutions to building problems. Yet, these solutions are assumed to be inapplicable to modern buildings. Despite some views to the contrary, there continues to be a tendency to consider innovative building technology as the hallmark of modern architecture because tradition is commonly viewed as the antonym of modernity. The problem is addressed by practical exercises and fieldwork studies in the application of vernacular traditions to current problems.

Vernacularism demands a relationship and adaptability of the built forms to the social,economic, ecological, and climatic environment. In a very broad classification, we observe two approaches to vernacularism: first is the conservative attitude and second is the interpretative attitude. While both the kinds of vernacularism have the ideals of bringing a new and contemporary existence to vernacular forms and spatial arrangements, they differ in the way they treat technology and community.

A more unadventurous approach to vernacularism, conservative vernacularism, inherits traditional construction technology and the use of local materials, linking both to the natural environment just like Hasan Fathy had done. It focuses on reviving building traditions based on a specific culture and society. Conservative vernacularism, however, is limited in building types, mainly focusing on residential development. It is a result of apathy found in the community concerning these forms.

Interpretative vernacularism, or neo-vernacularism, similar to the conservative approach, has emerged as an approach to bring new life to vernacular heritage for new and contemporary functions. However, neo-vernacularism's innovative approach utilizes different levels of technology as well as new types ofinfrastructures, such as

heating, cooling, and other technical services. This architectural approach is often used for commercial and tourist buildings and resorts because it incorporates easily recognizable symbols. This also helped to develop a new vocabulary of contemporary architecture which has its roots in the building tradition of a particular culture.

These two attitudes toward vernacularism, conservative and interpretative, which are based on building and cultural traditions, share clear objectives. First, the revival of the vernacular allows a more reasonable building environment, one that is more socially and culturally bounded. Second, by considering that traditions and cultural aspects can be involved in architectural forms and building techniques, it becomes possible for architecture to be honest to, and consistent with the immediate society. Finally, taking into account the possible and real effects of this emphasis, the architectural vocabulary of a specific regional culture can be reoriented and developed.

A culture steadily culminates these frameworks over time. Traditions then arise allowing vernacular designers to reuse forms and methods for common tasks. Contemporary designers typically look for a new or wholely unique solution to a given problem, which is counter-productive to creating traditions. The concepts of constraint, durability, and thrift provide the foundation for the vernacular’s evolutionary model. The same principles applied to modern-day design practice offer new and concrete ways for design to move forward.

Indigenous builders use local climate, culture and materials to guide their processes instead of years of formal schooling. The constraint of locality may limit formal elements, materials, and size to vernacular builders, but making choices inside the presented constraints allows for innovation to take place outside of initial expectations. Before the industrial revolution, around 200 materials were used in the building trades worldwide. Most of those materials were the same nearly everywhere: wood, straw, brick, stone and earth. Even with such a limited array of materials,

widely different uses and forms evolved in different locations. Specifying boundaries does not have to limit options. As a practicing designer, accepting constraints can make choices easier. When you don’t have 10,000 options, you can act quickly and confidently. Constraints play a large part in sustainability. However, sustainability itself should be the most important constraint on the design decisions we make. We can simply limit ourselves to only the materials that meet our definitions of sustainable. Indigenous buildings aim to get the most building for the least material, money, and time. Practicality is the focus. A building starts with something small and necessary and is only added to as money, time, and need allow. We have lost sight of this in contemporary design. We often seek the cheapest solutions monetarily, but we don’t always seek the all-around least wasteful solutions.

4. THE INDIAN VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

4.1 GENERAL

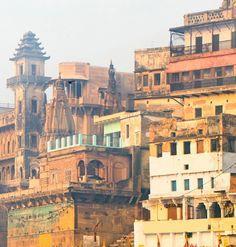

India is a country of great cultural and geographic diversity. Encompassing distinct zones such as the Great Thar Desert of Rajasthan, the Himalayan mountains, the Indo – Gangetic Plains, the Ganga Delta, the Ganga delta, the tropical coastal region along the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, the Deccan Plateau and the Rann of Kutch, each region in India has its own cultural identity and its own distinctive architectural forms and construction techniques that has evolved over the centuries as a response to its environmental and cultural setting.

A simple unit of the dwelling has many distinct forms which depend on the climate, the material available and social and cultural needs of the society. This architecture that has evolved over the centuries may be defined as “architecture without architects”. It is an evolutionary form of architecture which grows and alters itself with the changing needs of the society. The builders of these structures are unschooled in formal architectural design and their works reflect the rich diversity of India’s climate, locally available building materials, and the intricate variations in local social customs and craftsmanship. It has been estimated that worldwide close to 90% of all building is vernacular, meaning that is for daily use for ordinary, local people and built by local craftsmen.

4.2 HISTORY

‘When we look at the architectural heritage of India, we find an incredibly rich reservoir of mythic images and beliefs – each like a transparent overlay – starting from the models of the cosmos, right down to this century. And it is their continuing presence in our lives that creates the pluralistic society of India today’ – Correa.

India’s history is unique. Despite numerous invasions, conquests and colonisations it has managed to maintain a sense of continuity in its culture while absorbing aspects of other cultures and allowing them to be superimposed onto its own. Indian village life remains much the same today as it was years ago. Even in the fast paced modern cities such as Bombay and Delhi, what appears to be complete change of attitude and lifestyle is really only a surface veneer. Underneath, the age old verities, loyalties and obligations, largely stemming from religion, still rule people’s lives.

The roots of the Indian culture start with the birthplace of Hinduism and the concept of the VastuPurusha Mandala. It is a mathematical model that states the founding principles of the early Vedic priests: the mandala being a perfect square subdivided into identical squares. In simple terms, these geometric configurations were used to determine the layout of a house, temple or an entire city.

Moving on the 7th century, came the stepwells - an establishment of an elaborate architectural structure, the daily chore of fetching water is turned into a spiritual experience – true to the concept of mandala. These underwent metamorphosis with the arrival of the Muslims in the twelfth century and the introduction of the charbaghs or paradise garden.

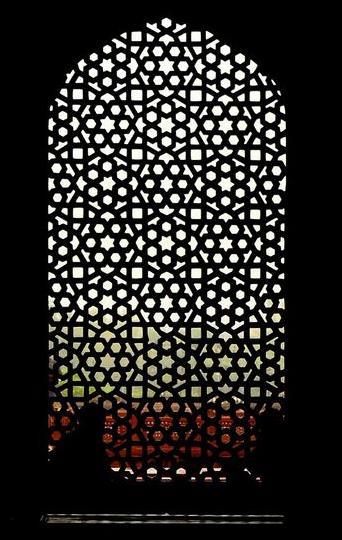

Spirituality and symmetry, the key ingredients of Hindu culture, proved also to be the basis of the invaders’ culture, and so the conquering Muslims found not only a reinforcement of their own architectural order but also the possibility of adding another layer of meaning to their own established forms. Islamic culture brought with it elements that have enriched India’s architectural vocabulary for centuries, such as the arch, the jali and the dome, and the ancient Hindu traditions of craft and a sophisticated grasp of mathematics, fueled by powerful mythology, pushed Islamic architecture in India to previously unscaled heights.

The arrival of the European colonial powers started a new and difficult period in the history of India. The values and aspirations of the Europeans were very different to those of the indigenous population. New styles of architecture such as, the melding of the Neo Gothic with the oriental motifs to form the Bombay Gothic, the Madras Indo Saracenic and the Classical Calcutta. This further lead to Edwin Lutyens Indianised Delhi.

Post-independence, Jawaharlal Nehru believed that India needs to industrialize and modernize. This encouraged the selection of modernist Le Corbusier as architect for the new city of Chandigarh. Le Corbusier’s powerful vision of the future would act as a catalyst for the eventual emergence of contemporary Indian architecture. His own definition of what is modern focuses on using elements of a culture’s history to create contemporary forms of expression that reinforce rather than destroy links with the past.

4.3 SOCIO – CULTURAL ASPECTS

Vernacular architecture is a concrete manifestation of society and its culture. The study of its anthropology highlights the nuances of human behavior and their beliefs in architecture. Traditions transcend themselves in the planning of traditional towns and architectural expression of the vernacular built form.

Religious rituals and community behavior also underline the study of traditional environments. For example, in the temple towns of South India rituals and festivals have played an important role in shaping the social and spatial disposition and form an underlying principle of the urban morphology of historic temple towns. The most eloquent example is the temple town of Madurai – the city is designed in such a way that the Meenakshi-Sundareshwara temple is at the centre of the city with five concentric squares defined by important streets. The spaces are designed in such a way that the religious processions can be accommodated easily. The streets were developed

as ceremonial axes with water bodies for annual rituals. The grid iron planning in the city of Jaipur is also based on the ancient Hindu texts which prescribe the strict geometric planning based on the concept of mandala.

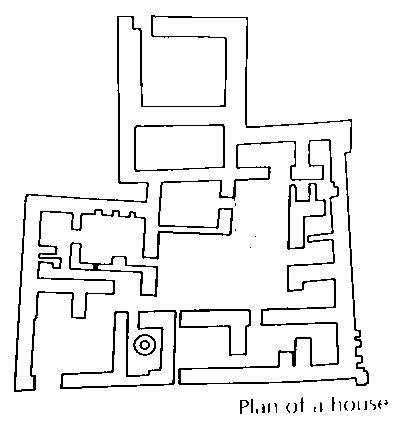

The design of dwellings is dependent on the eco-cultural response it has on the environment and is often built on the ancient knowledge systems of planning as well as construction materials and techniques. The basis of the traditional design in India is the vaastupurush mandala or a symbolic grid of ritualistic and functional activities. It is widely used for the design of traditional architecture across India.

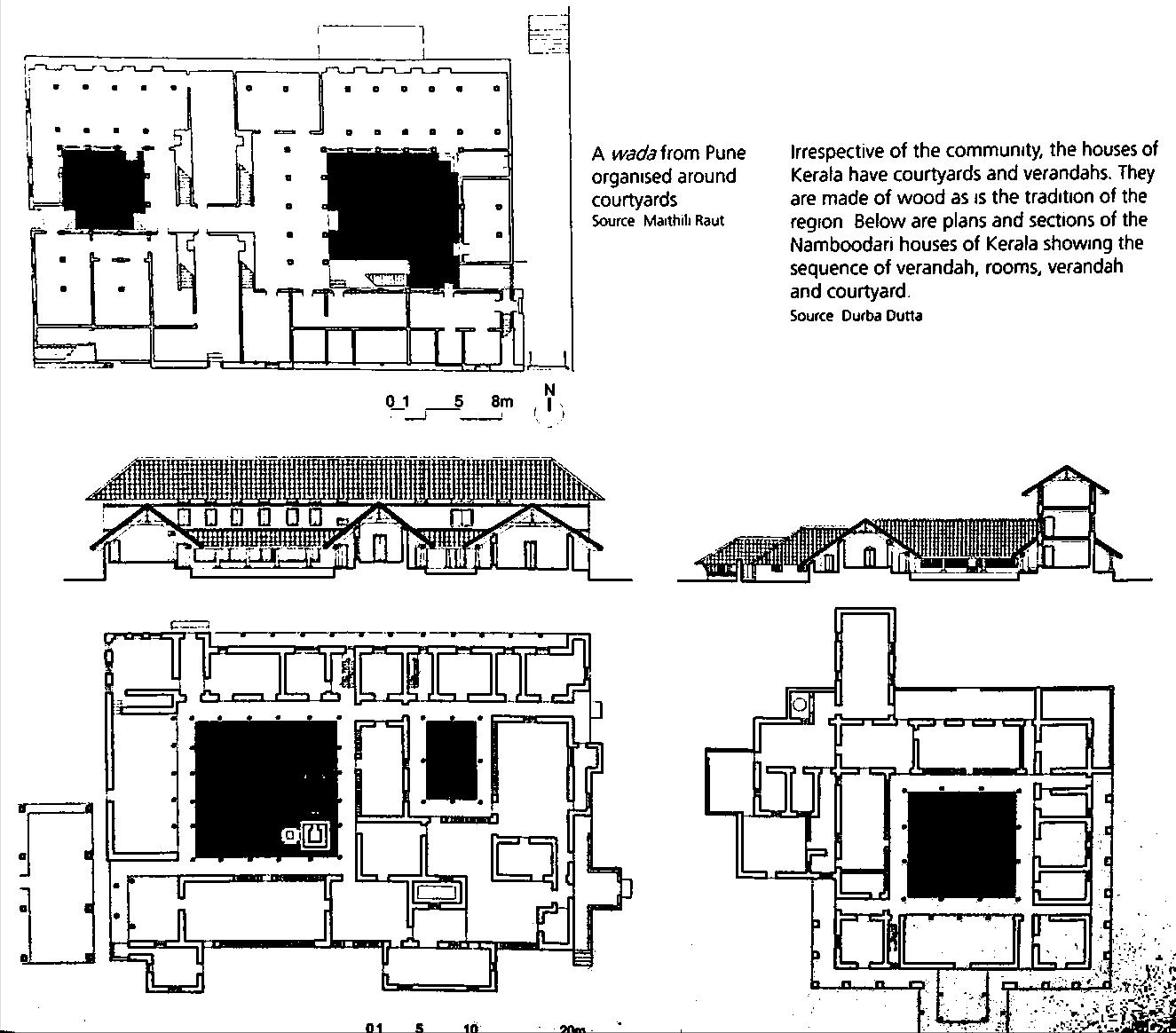

The courtyard house is the most common prototype of a vernacular dwelling commonly found in India. With regional varieties in design and craft techniques, a courtyard house is known by different names across India like the haveli in the Indo Gangetic Plains, rajbari in Bengal, the wada in Maharashtra, naalukettu in Kerala, and the Chettinad mansions in Tamil Nadu. The central courtyard is not only a good example of climate responsive architecture controlling the microclimate but is also a crucial multi-functional space used for preparing food, for playing by the children and for sleeping in the hot summer. It is the nucleus of all the activities of the house on an everyday basis as well as during important social and religious functions. The courtyard, the focus of cosmic energy, is therefore the most important zone of all traditional Indian homes, in functional, spiritual and symbolic terms.

“The house is built around a central open space ruled by Brahma, as per the vaastupurush mandala. Each side of the square holds one range of the house. Although various texts of the on VastuVidya are similar, the adaptation of dictates varies according to the region it is applied to. The materials, shapes and dimensions of the sub parts and the construction techniques must conform to the prescriptions.”

Social and religious patterns also play an important role in the design of neighbourhoods or mohallas, and in the individual dwelling units. For example, the

Muslim tradition of Purdah, did not allow women to be in public eye, and translated itself in separate zenana quarters within the havelis – balconies with jaalis – through which women could observe the outside world while remaining out of sight.

Social hierarchy in a community may also be noticed through embellishments. For example, in Ahmedabad, symbols carved in wood indicated if the household belonged to a Hindu or a Muslim family. The way a place is perceived and used by a community has a direct bearing on the planning of a settlement. In a vernacular environment, streets and chowks are the main spaces for social interaction and therefore acquire meaning not purely for their physical characteristics but for the meanings they hold for the users.

Vernacular traditions therefore offer themselves as an effective design tool for developing plans for sustainable habitats especially in the field of mass housing and slum re-developments. A common feature observed in most slum re-development schemes in urban India is that the squatter settlements are replaced with multi-storied blocks of flats. The design of these re-developed blocks largely ignorant of the way of life, social interaction, and community patterns of the intended users, encourages the dwellers to sell it to others and re-establish a new squatter settlement elsewhere. A few exceptions are Aranya Housing by B V Doshi and LIC Housing by Charles Correa. These have been built keeping in mind the dwellers’ preferred way of life and display sensitivity to the cultural context. The design for the SOS Village at Faridabad, Haryana, by Anil Laul is a striking example of this kind of architecture as it understands the way of life and the usage of space by the residents, and hence creates a habitat that is in sync with the dwellers’ needs and aspirations. By virtue if using design as a tool for ensuring the use of public open space and checking on encroachment, this scheme has been successful in understanding the cultural and the social nuances of a society.

4.4 ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS

The relationship between man and nature is reflective of a number of geographic factors like topography, climate, soil, water and vegetation. These factors determine the availability of local material, orientation of buildings, among various other aspects and also at times serve to be design determinants for the development of settlements. For example, the availability or scarcity of water developed a new typology of architecture such as baolis and stepwells. The imaginative use of locally available materials in a way to provide shelter from the climate transcends itself into the vernacular architecture of the region.

According to Vitruvius, the Roman architect, “Architecture is an imitation of nature, as birds and the bees build their nests so humans constructed housing from natural materials that gave them shelter against the elements”.

A hot dry season encourages massive walls on the ground floor. Incorporating elements such as verandas and balconies which provide shade during the hot dry period and also provide protection against rain in the monsoon denote architecture suitable for a given climate condition of the area. The barsaatis found in houses are an example of a sleeping quarter on the terrace use in the monsoon while the terrace was used for sleeping in the rest of the dry season. In most Indian traditional towns, a typical house was timber framed with brick infill and lime stucco on both the sides. Densely packed with a central courtyard along a narrow street, it projected a narrow frontage to the street. Often the street facades and the courtyards were richly decorated with intricate wooden carvings, reducing solar gain and providing options for thermal comfort.

As per the principle of convection, hot air rises from the courtyard and cool air entering the courtyard from a shaded street creates an environment of thermal comfort. This principle is used in the hot arid zones of Rajasthan, Gujarat as well as the Indo

Gangetic Plains and works best in the summer months. In the winter, the upper storeys and roofs which comparatively remain warm are used in the daytime. These patterns of comfort performance are reinforced by daily and seasonal living and household management.

4.5 UNDERSTANDING VERNACULAR DWELLINGS OF INDIA

Vernacular dwellings are inherently sustainable in design and are responsive to the climate, culture, and the socio-economic conditions of the area. As per the Bureau of Indian Standards, the country has been divided into five major climatic zones – hot and dry, warm and humid, temperate, cold, and composite. The typical vernacular dwellings of three climatic zones, namely, hot and dry, warm and humid, and cold were compared to understand the sustainability of each prototype.

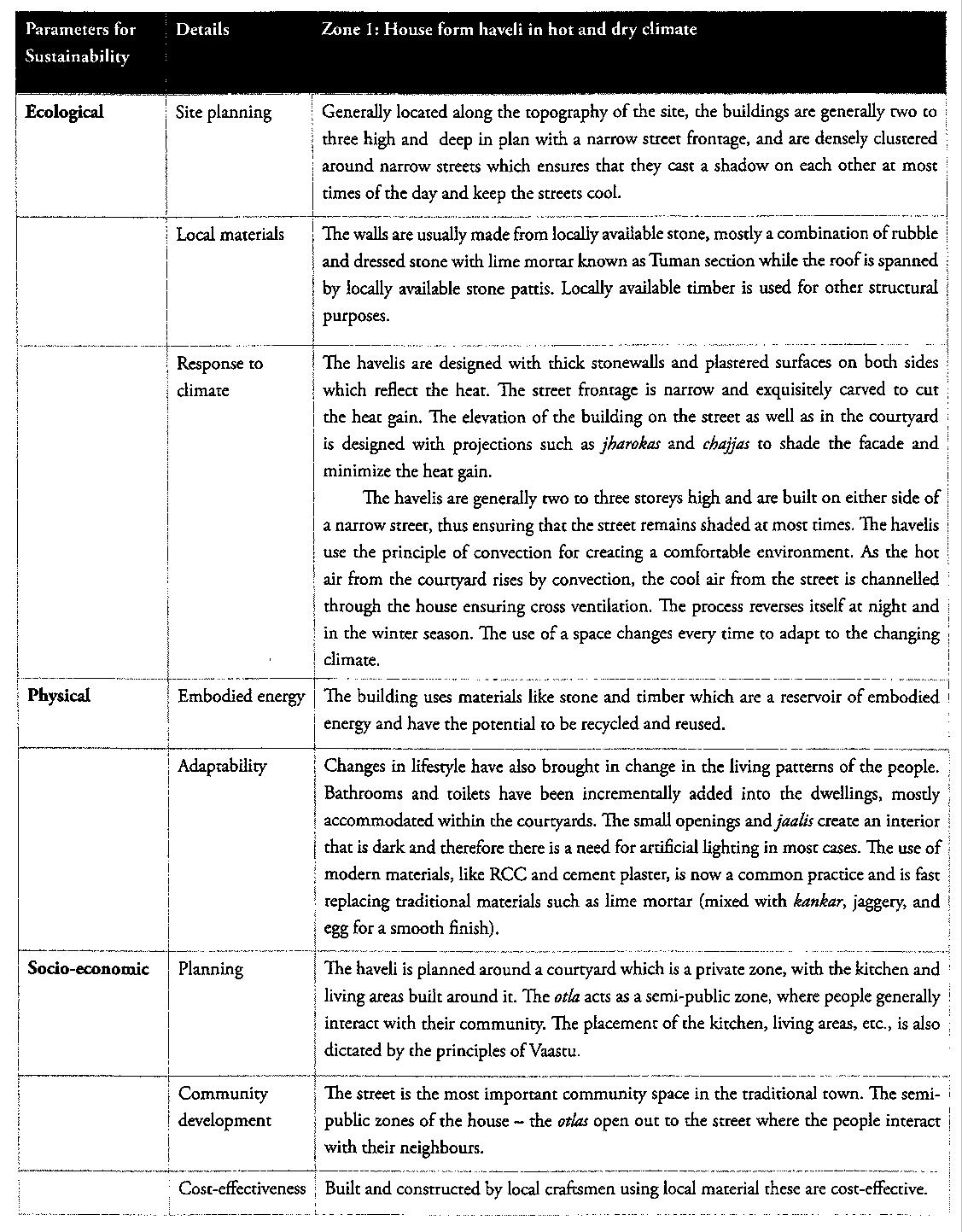

4.5.1 CLIMATE ZONE 1: HOT & DRY

Situated in the north western part of the country, the Thar Desert covers the states of Rajasthan & partly Gujarat. The climate of the desert is hot and arid with scarce rainfall. The vernacular architecture of the desert is an artistic expression of the climate and the culture of the region. The people of the region have evolved a lifestyle with the judicious use of the available natural resources. There is a distinct divide between the kuccha and the pukka vernacular architecture of Rajasthan. The kuccha is defined by the dhani in Rajasthan and the boonga in the Kutch region, while the pukka architecture is dominated by the haveli kind of architecture.

Table 1

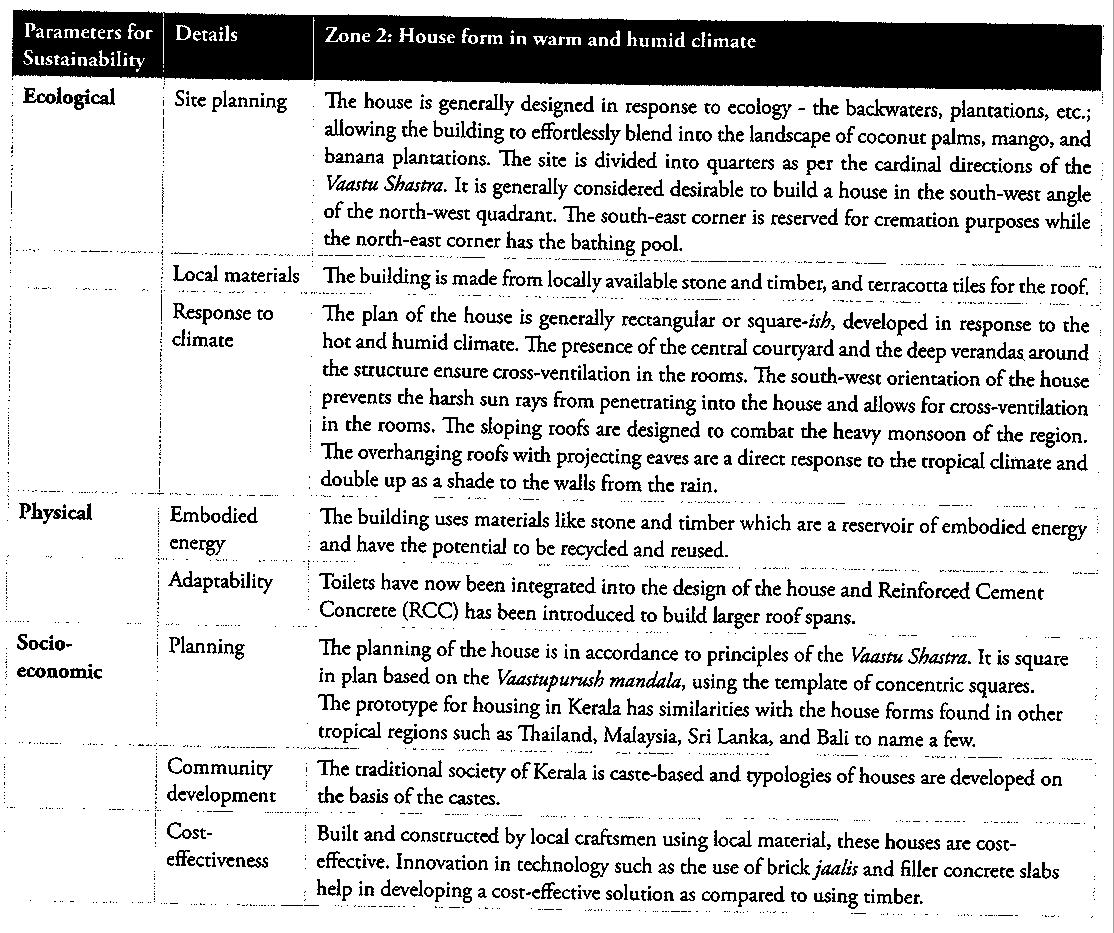

4.5.2 CLIMATE ZONE 2: WARM AND HUMID

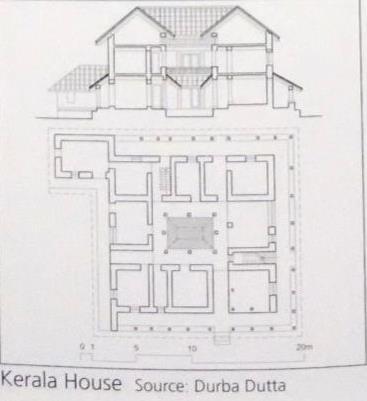

The state of Kerala has a very distinct topography. Located on the south western part of the Indian subcontinent, it has its own cultural and linguistic identity. Bound by the Arabian Sea in the west, and the Western Ghats in the east, Kerala has a warm and humid climate and a heavy monsoon for three months in a year. Its extensive rainforests are a considerable source for high quality timber and have dominated the vernacular architecture of the region. Contrasting to the rural settlements in the rest of India, in Kerala the unit of the rural settlement is the house itself; usually isolated from others it is self-sufficient with its own source of water, temple, bathing place and agricultural land.

Table 2

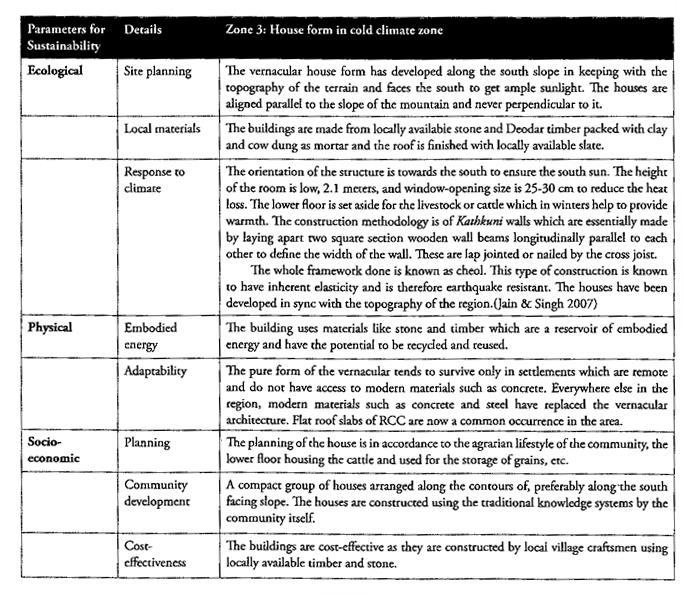

4.5.3 CLIMATE ZONE 3: COLD

The district of Kullu forms a transitional zone between the Lesser and the

Greater Himalayas and presents a typically rugged mountainous terrain with moderate to high relief. The climate in this area is pleasant in the summers with heavy rainfall and moderate to heavy snowfall during winters with the mercury dropping below zero for a short period. The economy of Kullu is mainly agricultural and people spend a lot of time on the fields and looking after their livestock.

Table 3

4.5.4 OBSERVATIONS

The comparative study of the typical dwellings of the three climatic zones indicates some common features which is the reason for its inherent sustainability. These principles can effectively be applied in contemporary architectural practices to produce sustainable built environments.

The site planning should ensure that the orientation of the building is such that it restricts the harsh sun, yet allows for daylight access and cross ventilation. It should ideally be designed in response to the sun paths, wind directions, and allows for passive cooling by means of shading devices such as balconies, verandahs, jharonkhas or jaalis. Window openings should be generally along the southern or northern facades with adequate provisions for shading. The site should be planned in accordance with the existing flora and fauna to create an environment which respects the ecology of the site. Locally available materials should be used in conjunction with the modern materials so as to get what is valuable from both the vernacular as well as the modern technology. For example, innovations in bamboo composite construction in the north east or the use of bricks and filler concrete by Laurie Baker in Kerala are some methods.

The designs of the habitats should be in sync with the way of life, religious beliefs, and customs of its inhabitants and optimal use of space should be propagated. The use of locally available craftsmen and masons is advocated for creating cost effective sustainable buildings.

5. LEARNING FROM VERNACULAR SPACES

5.1 GENERAL

Indian architecture, generally speaking, conjures up images of huge temple spires and gateways, large fortified palace complexes, mosques and tombs. These are often embellished with exquisite carvings and intricate stone inlay work. The monumental is enriched by the delicate details. This is achieved with the help of a sophisticated geometric organisation of built forms and spaces. On the other hand, there is the mundane domestic architecture with its occasional flair for refinement. Yet

there are spatial features that retain continuity and scale, playing an instrumental role in the characterisation of Indian architecture.

But there is more to the spatial order that runs right across this enormous range of building types. A large part of this order emanates from its own meaning as built space rather than from the specific function it caters to. There is a range of spaces, irrespective of the material and the construction methods that are built, as if for their own sake. This is essentially to create a ‘spatial opportunity’ for things to happen and they do. The meaning is in the space itself and the range of activities it can accommodate and not in the specificity of the function.

The following topics are means to understand from the elements, spaces and principles of vernacular Indian architecture, namely, movement, courtyards, facades, minimising, light, structure, pavilions, transition spaces, floors, columns, walls, doors, staircases and roofs.

5.2 MOVEMENT

Besides paving a way for connecting one place to another, movement provides an opportunity for experiencing spaces and forms that are articulated around it. In a way, it narrates the script inscribed in the spatiality of the place. Planning for movement in order to satisfy basic functional requirements is one thing, conceptualising spaces around the movement is another. There are numerous examples where movement plays a deterministic role in spatial organisation and the central concept revolves around this theme as well as manifests through the design. Structuring movement in design addresses the joy inherent in the act of designing as well as in an engagement with functionality along the way.

Historically, there are several examples where the conception of movement stands out very strongly and is the key determining factor in the plan. It not only helps visualise the use of spaces inside or outside the buildings, but also governs the way people are connected to and across spaces. Such conceptions predetermined, in a readable sense, the way forms evolved around the central idea of movement.

While movement is integral to all architecture, the intention is to look at buildings, complexes or precincts where the basic conceptualisation is inspired by the idea of movement. It is seen as a generator of a design concept with all other aspects finding their respective positions in relation to this focal idea. Each situation involving movement brings forth an expectation which can be addressed through richness in conception or through a mundane utilitarian answer. Vernacular architecture, in this context, then, can be seen as a dominant expression of movement, both as a connecting force and a generator of spatial experience.

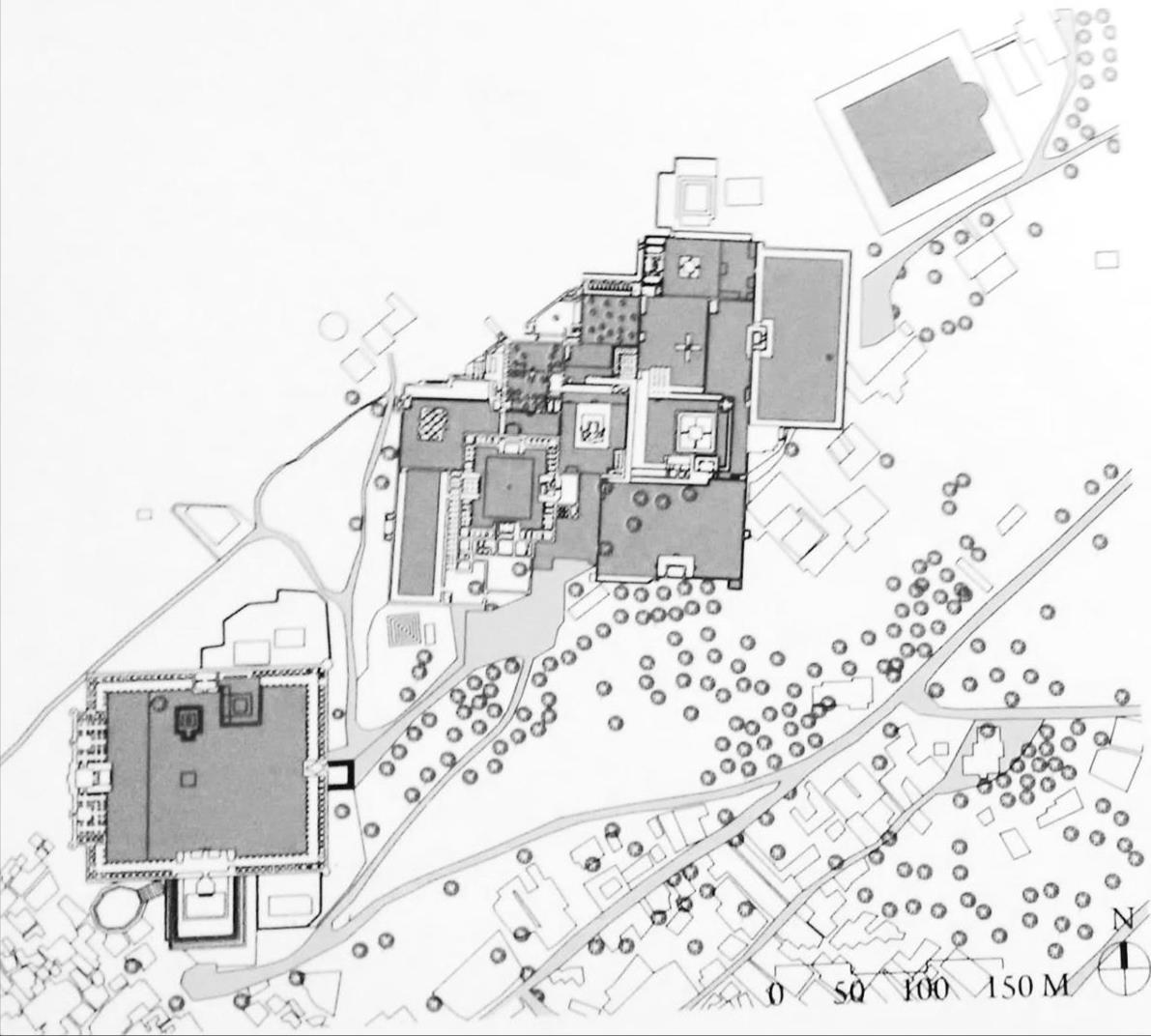

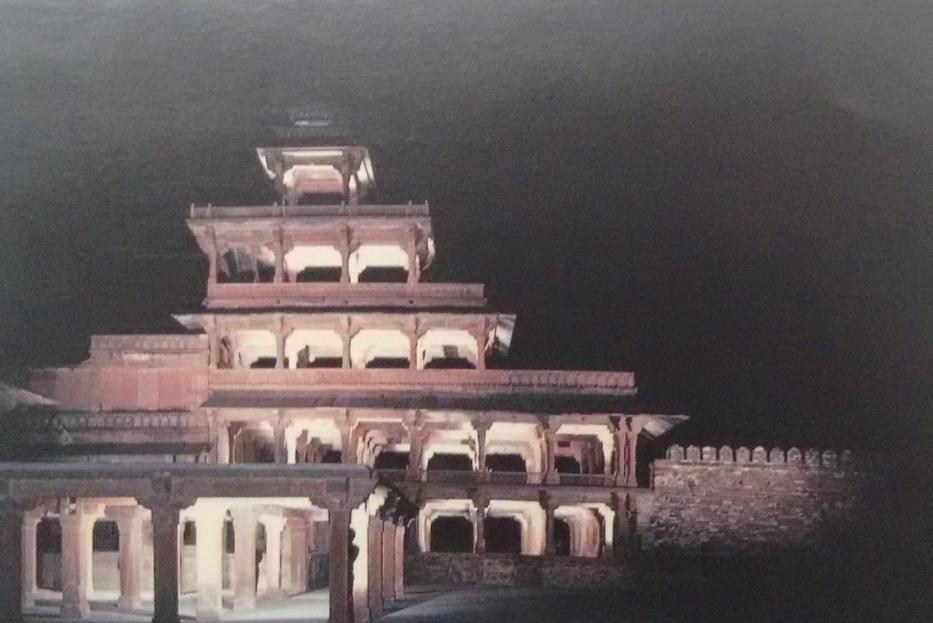

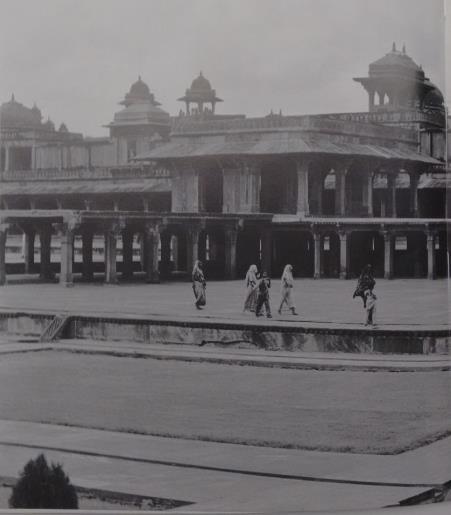

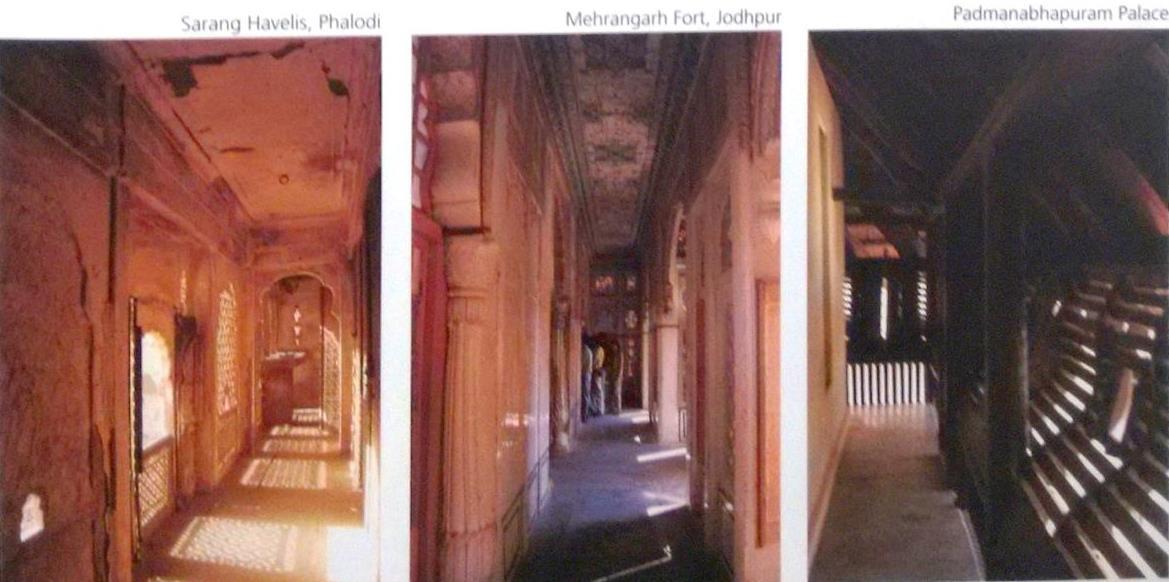

The significance of a place and its function, expressed through movement, does not diminish in value with changes in scale or context, or if it moves from the inside to the outside. It is useful to understand, how, in several multi-building complexes one moves from one space to another along no clearly defined paths. At times, it is even difficult to orient oneself. Yet movement happens within a rich spatial experience. Look at the core complex at FatehpurSikri or at Amber, or Mehrangarh Fort where movement takes place from one courtyard to another or from one space to another along no defined paths. However, at all these palace complexes there are paths leading upto the gates or the main entrances, but once inside, an altogether different pattern of movement emerges. These palaces demonstrate highest level of spatial connectivity. While few buildings are accessed from outside by paths, all internal movement within the complex is through the spaces.

Figure 10

Fatehpur Sikri complex is one of the finest medieval palace complexes which demonstrate highest level of spatial connectivity. While few buildings are accessed from outside by paths, all internal movement within the complex is through the spaces.

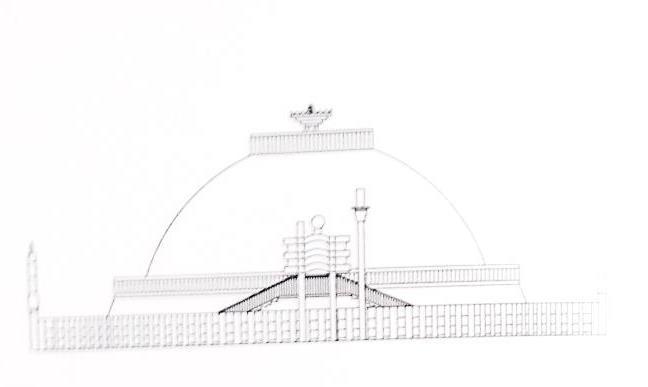

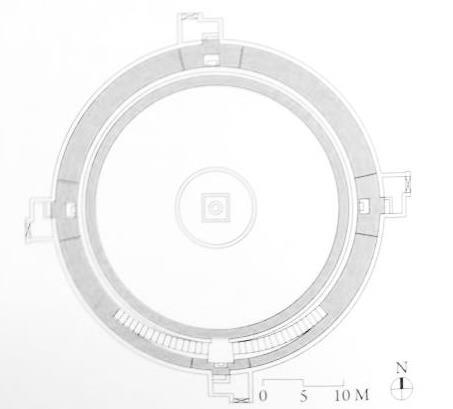

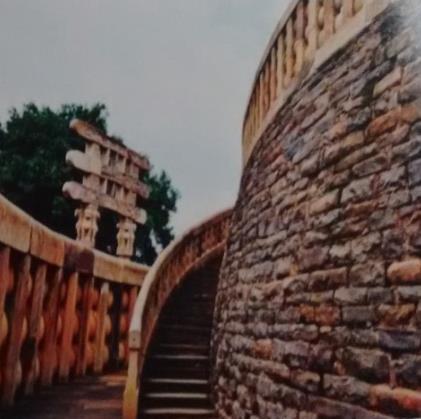

Over centuries, ceremonial events, including rituals, religious, military or royal, have contributed to the special attention paid to the formal structuring of spaces dealing with movement within the overall scheme of things. A parikrama, normally situated around the core of Hindu religious places, when connecting many sacred places of religious significance however, can run into several kilometres. Or a pradikshana, which is normally to be found around a central place of worship, like a temple or a stupa, can even be located within a building – a space that circumambulates a formal walk around a shrine, an idol or a temple. For example, the Buddhist Stupa at Sanchi is distinctly elaborate in its manifestation of the same.

Be it for a temple or a stupa, there are aspects of cultural meaning that are significant for each religious group, the plan organisation must take into account these expectations of special movement; either by simply connecting the places or by providing a circumambulatory path or both. An enriched design opportunity can be created by paying special attention to the design of elements that can help manifest such activities.

Speaking of Sanchi Stupa, Kostof explains “This upper circumambulatory path also has a high balustrade modelled, as are the toranas, on wooden prototypes. Here, on this narrow and paved path, the pilgrims went around the axis of the universe in its domed cosmic shield, touching the source of their faith that would make benign the real world on their way back home.”

Figure 11

Figure 12

Sanchi Stupa Figure 13

Movement also provides an occasion for as well as a manifestation of celebration. It creates an imagery of spatial experiences as one moves along and invokes actual or perceptional pauses. It is the design of this element of movement that either provides for these pauses or avoids them in a conscious manner. Be it in the ceremonial, ritualistic, recreational or simply functional aspects, movement has a rather carefully articulated spatial presence or occasionally it is allowed to just happen. There are several examples where one can see that movement is central to and forms the basis of the entire conceptualisation of a building or a group of buildings and it is so expressed, both in the formal as well as informal organisations of spaces.

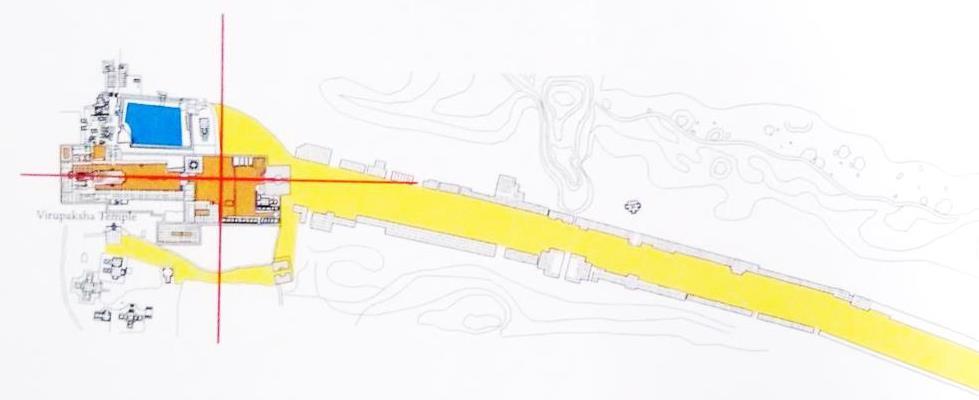

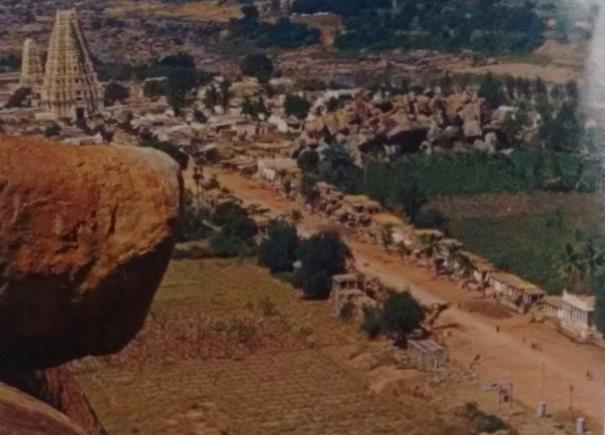

Vijayanagara at Hampi, is set in the midst of an extraordinary backdrop. It is a very interesting example of multiple factors governing spatial organisation growing around several religious as well as secular functions. The orientation of the temples and the paths is negotiated keeping in mind the unique landscape. There are patterns of movement, in Hampi, that are constant and there are patterns that reflect change. The orientation of the main temples is aligned along the cardinal directions, the axiality of the paths given their dominant presence within the hilly terrain adjust and respond to these cardinally oriented structures. Beautifully articulated, the two aspects come together without any conflict. Articulating movement within the overall plan is one thing, adding meaning through design is another. At Hampi, through the movement axiality provided by the dominant presence of the paths, a contextual adjustment of intent and a circumstantial manifestation of the same, successfully bring together all the aspects.

The point of interest here is the conception of a path of movement that simultaneously addressed the issues of connectivity, formality of spatial organisation and the possibility of religious rituals being linked with movement. Above all the negotiation with topography demonstrates the values of the design attitude. Today, in many contemporary designs, one finds willful manifestation of geometry, here it is contextually relevant and defines its logical meaning.

Plan of the street connecting Virupaksha Temple and Nandi at Vijayanagara, Hampi

Figure 14

Virupaksha Temple set to the cardinal direction. The path is aligned with gap between the two hills. Figure 15

View from top showing Virupaksha temple & the path Figure 16

Figure 17 Figure 18

5.3 COURTNESS

‘Courtness’ an intrinsic quality, to be found in several built manifestations of enormous diversity, has remained a timeless quality of architecture across the world. Integral to courtyards of various functions and scales, this attribute is what informs the sense of life in courtyards. There are courtyards which are deeply evocative of life and then there are ones that do not suggest much activity. It is in this distinction that ‘courtness’ comes into play. The prime determinants and the key to the success of courtness revolves around the conditions governing the edges of a courtyard, porosity, ease of spatial flow and inside-outside connectivity.

Courtness is really a term devised a s a noun to highlight the intrinsic qualities of interior open spaces, which are often called courtyards. The purpose is to arrive at those aspects of courts which make them meaningful in their conception and application. The idea here is to recognise the hierarchical flow from enclosed to semiopen to open spaces that allow activities to flow into the open. The directness and the ease with which this may happen and the manner in which the court might receive these activities would determine the value of courtness. It revolves around the idea of

how an open space operates within a building. It is an idea that expresses the spirit of the courtyard in an active manner. It represents the intrinsic value of a courtyard as a manifest form that inspires activity. Internal open spaces, in the form of courtyards, are a thematic element in all spaces of vernacular architecture. From small urban houses to large mansions and palaces, courtyards became the key organisational elements responding to climatic conditions as well as the cultural needs of communities. It is an internal space within a building or one created by a number of buildings that surround a space and are thus instrumental in the evolution of the resultant courtyard(s).

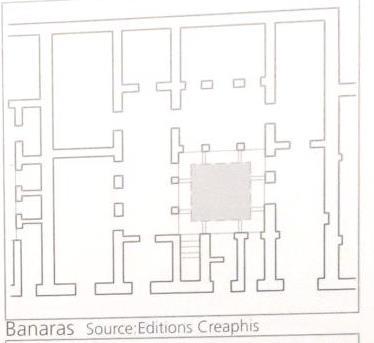

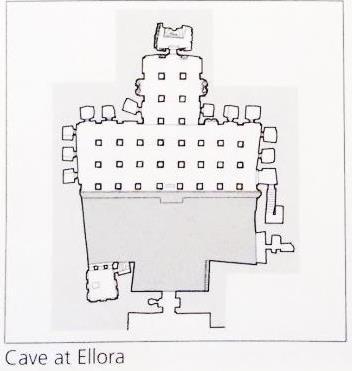

Climate influences on spatial organisation are apparent in the centuries since 2000BC during which the basic principle of a central court with rooms all around it, has continued in the Indian subcontinent. Looking back in time, searching for the origins of the courtyards leads to the houses of Mohenjodaro and Harappa. The built forms then had central open-to-the-sky spaces. They had no windows facing the street, but concentrated on the courtyard. Considering the climate of the region, it can be deduced that these internalised houses would have depended on the courtyard for light and ventilation.

The essence of this space has remained unchanged over thousands of years. Variations of the theme were created depending upon different socio-cultural patterns and unique site conditions. Some of the cave architecture also shows the use of courtyards. The courtyards contribute to its spatial quality beautifully by bringing in a subdued light, creating a peaceful environment.

2. 1. Plan of house in Harappa Courtyards in cave architecture. 3. Part plan of Mohenjodaro

Figure 19-23

This reveals the punctures in the built forms that could be central courtyards. Houses were fashioned in a manner very similar to those found today in the northwestern regions of India as seen in the detailed plan of the houses. Courtyards were present in individual houses as well as in public institutions

A courtyard with a strong central position provides easy access to several parts of a house. This encourages the spill over of various activities like in a traditional house for cooking activities, for families to sit together and eat and later for other household activities. Courtyards address life, or the absence of it, and they draw up a meaningful framework for the understanding of this space, which may be seen as the timeless core of architecture. The meaning that can be derived from this aspect can be found embedded in its spatial quality, in the matter of connectivity, in the scale and nature of transitions, in the level of transparency between the inside and the outside in providing visual access, and so on. It is also important from the point of view of the level of comfort it provides in various climatic conditions.

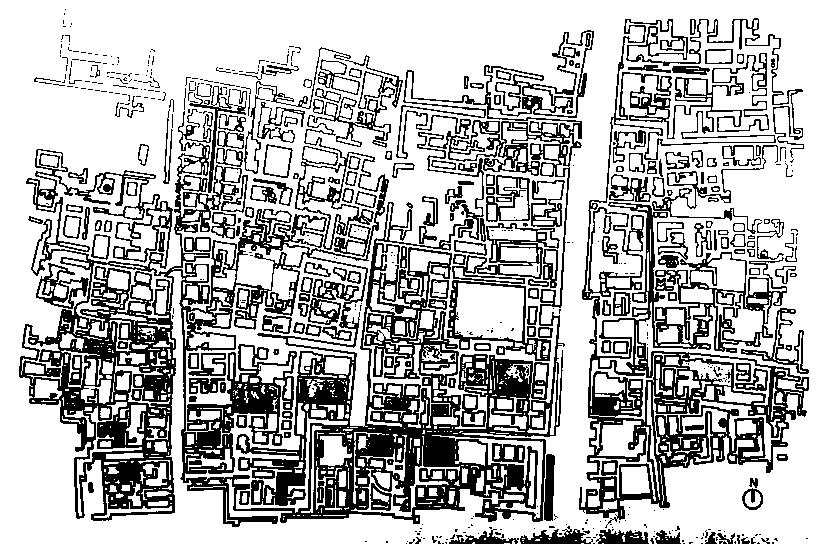

Most domestic architecture in India is organised around central courtyards. A courtyard’s position becomes that of a principal space organising element. This room without a roof is often bounded by verandahs along its periphery. Other rooms open into these verandahs creating a spatial organisation based on a hierarchical sequence of spaces ranging from open to enclosed. The rooms get their light and ventilation from this courtyard and have very few opening’s onto the exterior. This spatial sequence encourages the intermittent flow of activities responding to various private needs. Also, the tropical climate of India demands air movement as well as shaded spaces for comfort. The open, yet protected spaces, become the heart of Indian living. An open to the sky area within the living premises offers an ideal space in terms of light, ventilation, connection and privacy from the outside world. The passage of time can now be directly experienced from inside: changing of the seasons, movement of the sun from dawn to dusk. Chance encounters or deliberate interactions bring the family together here. The courtyard with its surrounding verandah becomes the living room of the house, both literally and figuratively.

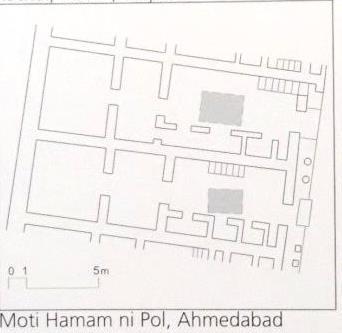

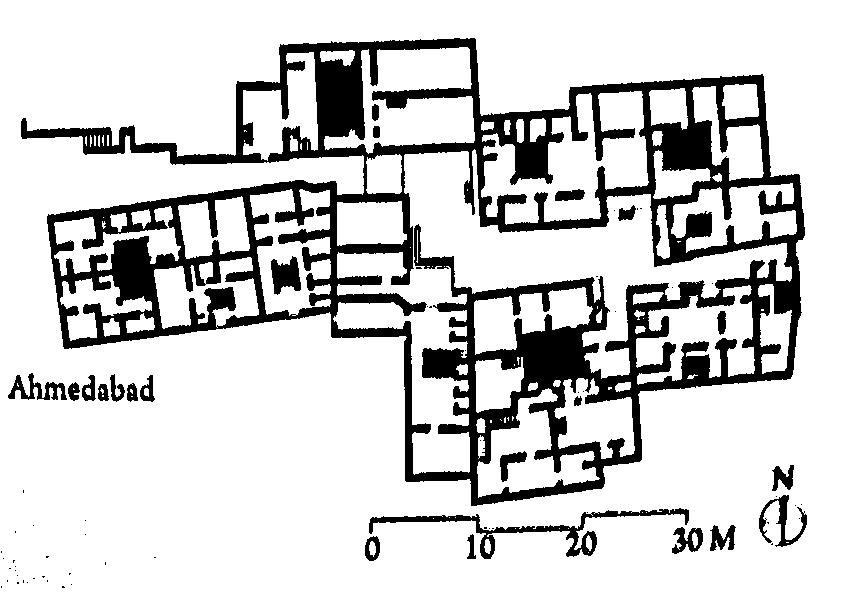

Figure 24-29

The courtyard also becomes the primary source of natural light and ventilation. What began as primarily a functional space with its genesis in climatic requirements has now become the soul of the house in the desert, especially in towns and villages that have denser fabrics. The courtyards of Rajasthan which are now world famous have intimate scales, articulation with carved stone and a subdued quality of light. With house built back-to-back to protect them against the sandstorms and harshness of the sun and very few openings possible in the exterior walls, the courtyard becomes vital to provide for light, ventilation as well as an outdoor activity space. The pols of Ahmedabad, a distinct urban fabric, show this characteristic. The houses are long and narrow, with central courtyards. Narrow streets, with houses often back-to-back, limit the amount of natural light that can be brought into the houses. Courtyards hence serve the purpose.

In certain climates, particularly warm, it is normal for household activities to spillover to the outdoors. This makes the edge between inside and outside a very important element. In small houses with one or two rooms, it is normal to see this extension of the house onto the street – a transition on the edge. However, in larger and wealthier houses, there are courts offering a similar edge between the court and the inside, a similar transition, except that there is more privacy. A small study of the village of Kutch shows this very clearly. This village is not an exception, most house; rural or urban demonstrate this quality of spill-over on to the street.

Figure 30 Figure 31

Houses in the towns of Kutch show an extension of household activities into the courtyard. It remains the central activity space in any house irrespective of size, as there is a great flexibility in the manner in which spaces are used.

1. A courtyard in a pol house is separated more by the quality of light than the enclosing elements like walls. It is a continuation of the surrounding spaces.

2. Moti Haman ni Pol, Ahmedabad. The plan shows the central courtyards in the long, narrow houses creating a honeycomb pattern in the urban fabric.

Figure 32-34

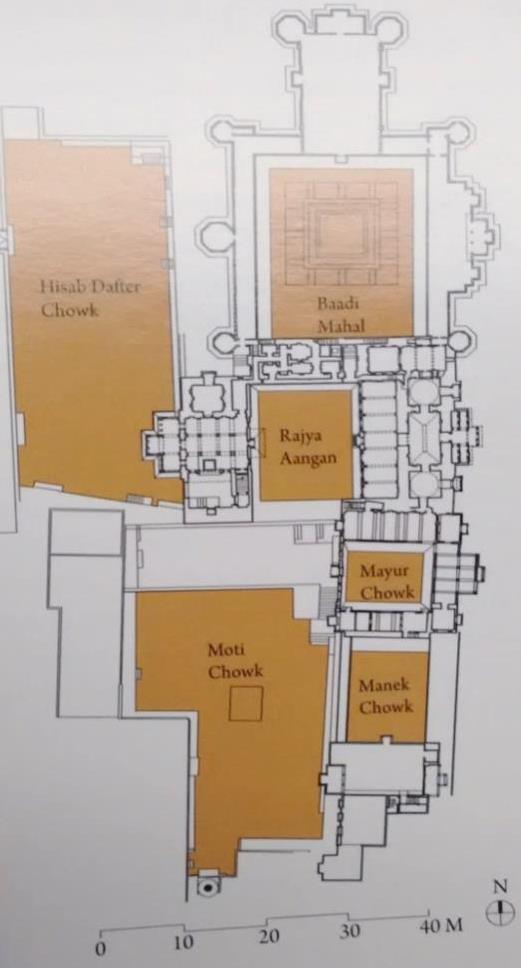

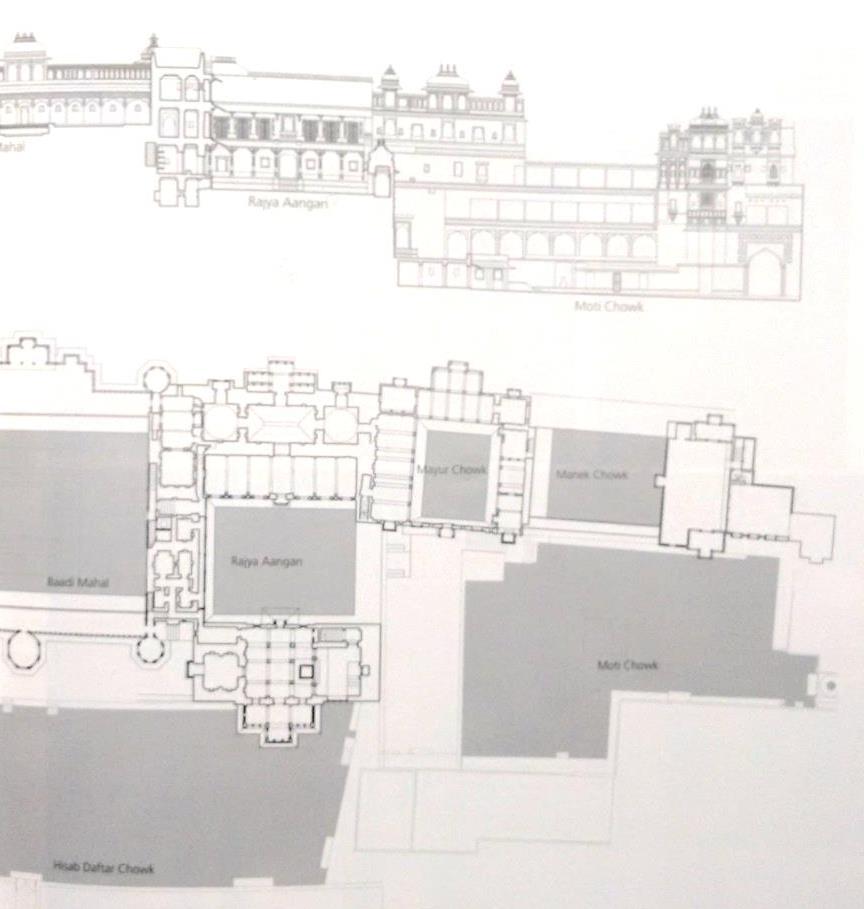

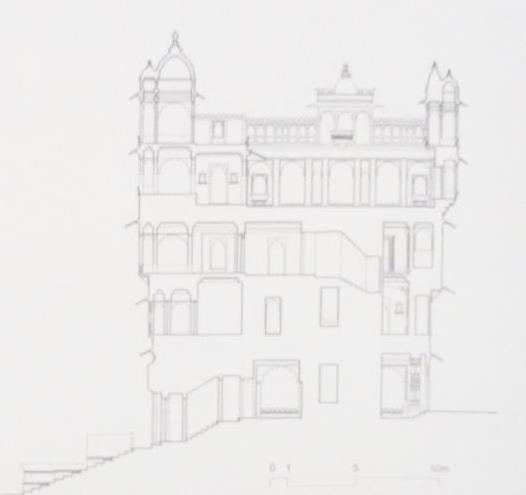

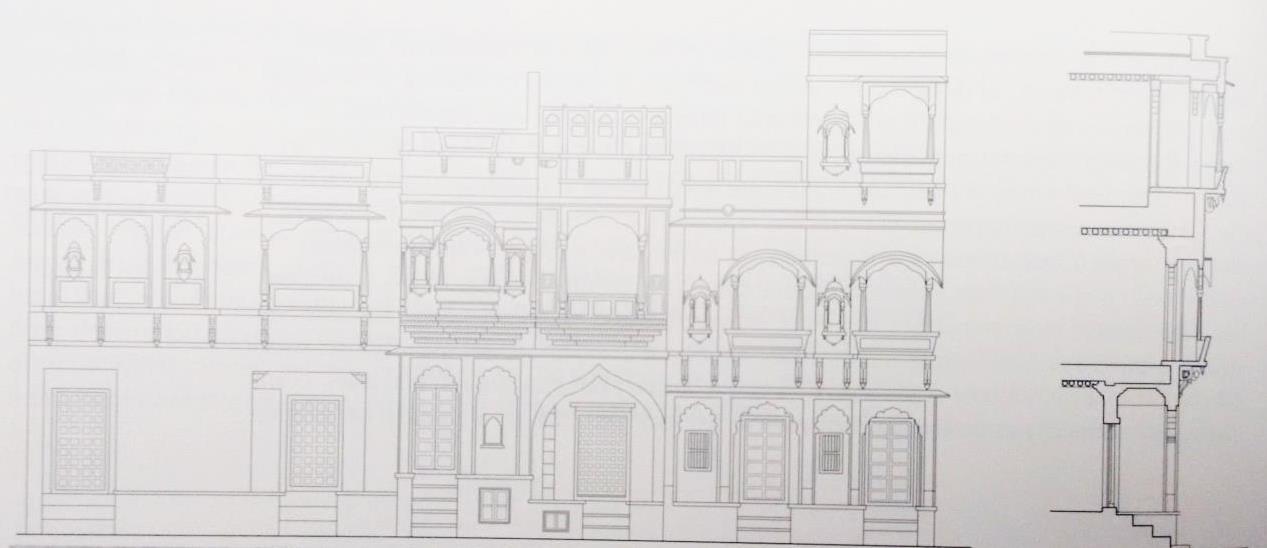

Variations in the generic form of the courtyard come from changes in materials, articulation of the enclosing elements, scale, proportion and complexity of plan. The Mardana Mahal, Udaipur, is an arrangement of courtyards and terraces of different scales and articulations. Each of them was made for a specific purpose and reflects this in its making. However, the essence of an open-to-the-sky space that brings in a natural gradation of light quality while generating a comfortable microclimatic condition enclosed by a semi open verandah remains the same. They are enclosed worlds within themselves with little visual connection with the rest of the palace and give the sense of being art of smaller individual residences rather than a larger one. The Baadi Mahal was for relaxation while the Rajya Aangan is the court in front of the temple. The Manek Chowk and Mayur Chowk were domestic in nature. Courtyards also occur at several levels apart from the ground floor. In the Mardana Mahal, there are many courts at various levels considering that the place is built on top of the hillock. Each courtyard defines a particular function of royalty and has a resultant articulation. Colonnaded verandahs, elaborate zharonkhas or blank walls enclose courtyards depending upon its position in its overall schema.

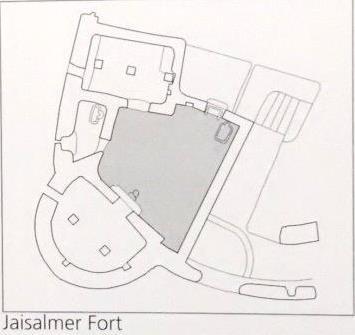

There are examples of buildings which originally were not open to the public, like several palaces and royal homes. But, with changing times they have come under the public realm in the guise of museums, hotels and heritage properties. Thus, offering changed spatial and functional meanings. Palace complexes like the Mehrangarh are the finest examples of courtyards once meant for private use being successfully adapted to public use now. And then there are some very beautiful courts which have played a crucial role in the makings of architecture, sometimes purely for aesthetic reasons like the Diwan e Khas in Amber, Jaipur; Srinagar and Holi Chowk at Mehrangarh, Jodhpur and the Peacock Court at the Udaipur Palace.

Mardana Mahal, Udaipur is an arrangement of courtyards and terraces of different scales and articulation. Each of them was made for a specific purpose and reflects in its making. However, the essence of an open-tosky space that brings in a natural gradation of light quality while generating a comfortable micro climatic condition enclosed by a semiopen verandah, remains the same. They are enclosed worlds within themselves with little visual connection with the rest of the palace and give the sense of being part of smaller individual residences rather than a larger one.

Figure 35-37

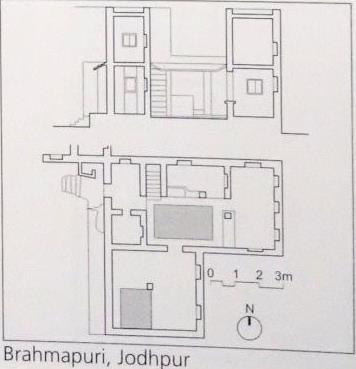

Jain states: “The city of Jodhpur was a fortified town ringed on all sides by massive sturdy walls and bastions with seven impressive gateways. Rising in the middle is the daunting citadel of Mehrangarh, an invincible fortress within which are juxtaposed exquisitely carved stone palaces. It boasts of a traditional urban fabric which reflects the culture, climate and geography of the region. The fort was surrounded by a settlement demonstrating intense urbanity with court houses. The palaces, with lavish interiors, are built around courtyards with exquisitely carved zharookhas on their facades.”

These courtyards, despite royal intent, are very intimate in scale and connect beautifully to various other spaces. The organisation of the covered spaces within the courtyards is more like pavilions connected directly to the outside spaces. In these arid regions, there was a porous relationship between the inside and the outside which made a lot of sense for climatic reasons. It was normal for activities to spill over into the courtyards. Celebrations and events were regular features of such spaces. The interior-exterior relationship of the palace courtyards worked beautifully for royal activities; they work extremely well now too, as public spaces-feudal spaces democratised. A large number of people move through these spaces, experiencing the inside as well as the outside.

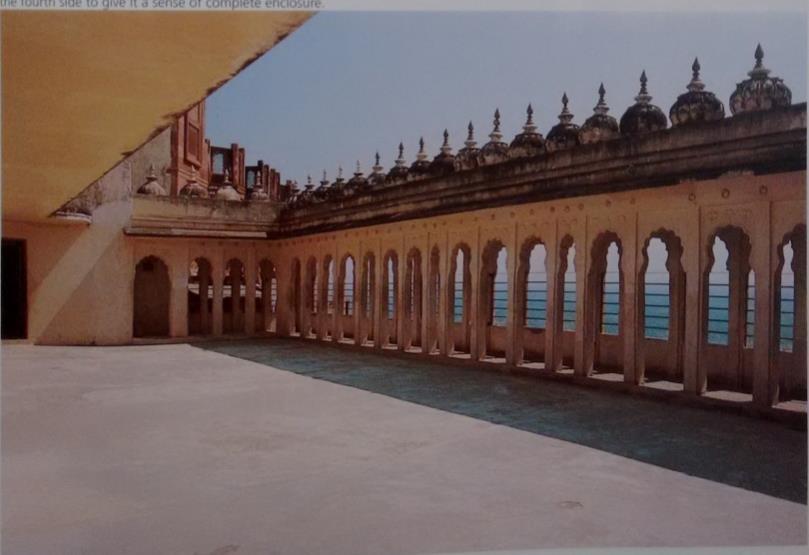

Ajit Vilas Chowk, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur is a terrace with the palace rooms on three sides and a verandah overlooking the city on the fourth side to give it a sense of complete enclosure. 46 Figure 38 & 39

Srinagar Chowk of Jodhpur fort was the site of royal coronation. This made it the most important space and is therefore elaborately carved and monumental in scale.

Figure 40

Figure 41

Figure 42

A courtyard is an integral part not only of northern India but also of the house in Kerala down south or a wada of Pune in central India. The material changes from stone in the north to wood in the south. The spatial organisation remains similar with the courtyard being surrounded by a verandah and rooms. In Kerala, the rooms are more porous to the outside since the houses are not back-to-back. Also, the requirement of cross ventilation is much higher considering the high level of humidity. The courtyard provides for this much needed cross ventilation. It allows for an increased depth in the house. The courtyard is thus developed as an element to generate a microclimate within the house that is comfortable.

Figure 43

5.4 LIGHT

Religious structures for thousands of years have demonstrated, beyond doubt, that light has a special meaning in engaging with such spirit-the divine experience. At times, secular buildings have also addresses the subject of light as a central idea for public spaces. New institutions have sought new meanings by capturing light as the central theme. While the demands on light would have their roots in functionality, the extension of such a role can create memorable experiences of beautifully lit spaces.

Man’s engagement with light –architecture connect has been intrinsic to the building process. Incorporating the structure into the process has added greater meaning to design. Irrespective of the building, the builder’s preoccupation has been to draw light from the top-a sense of divine light. This also served well to light up deeper and darker interior spaces.

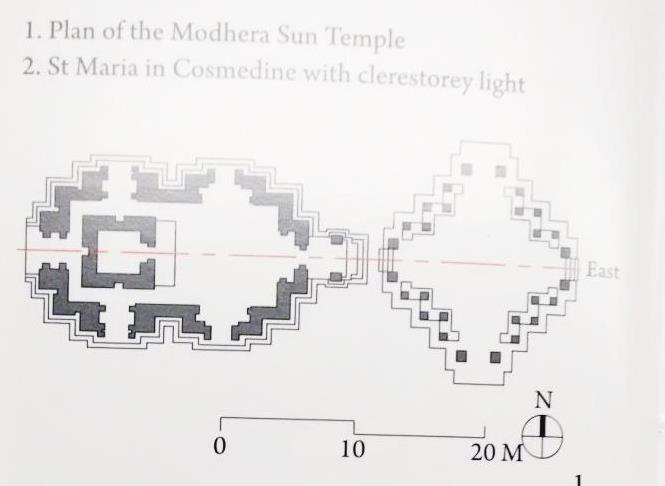

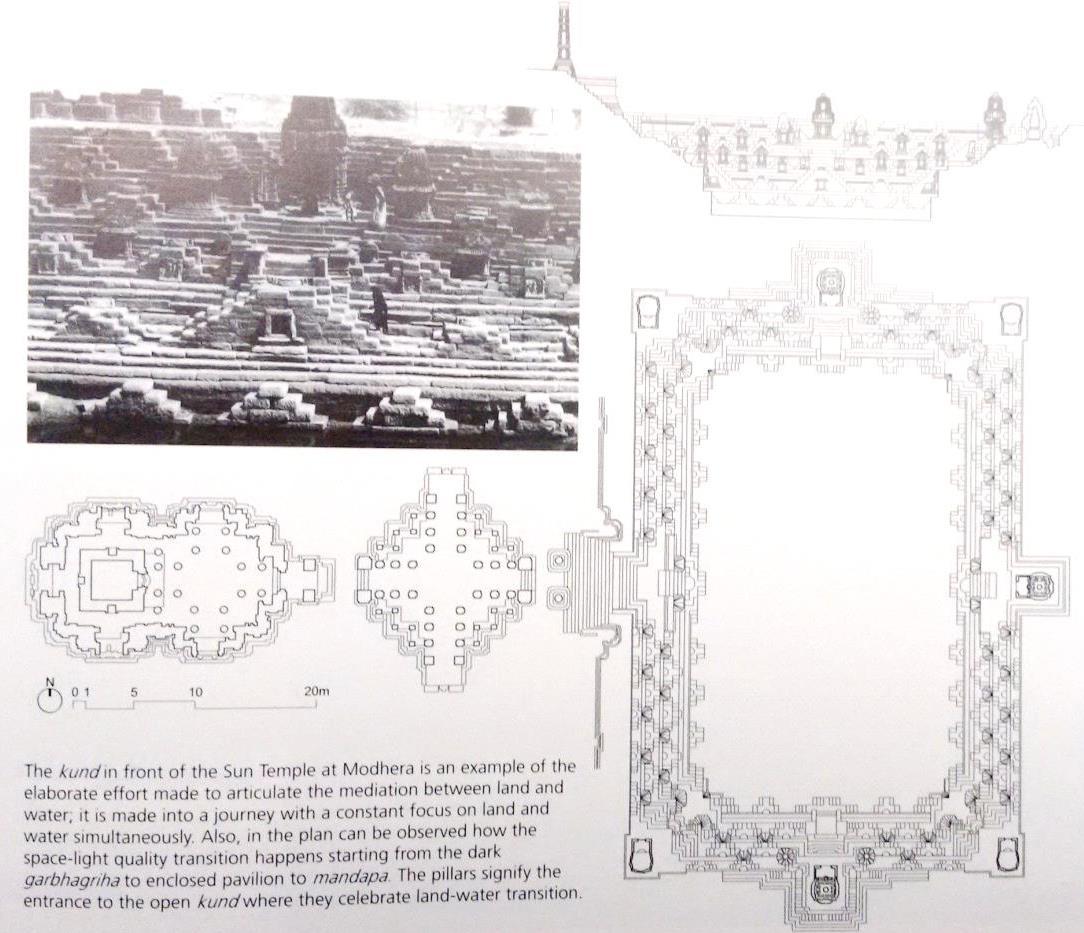

The design of the Sun temples incorporates a special consideration for light. They have a different perspective since their organisation has a special cosmic relationship vis-à-vis their spatial configurattions. And, of course, they follow a very sophisticated astronomical system of positioning in order to capture the morning rays of the sun in a presetermined manner. These temples were so designed as to cause the morning rays of the sun to fall upon the images of the Sun God, a meaning of greater religious significance than the quality of divine light. Although there are quite a few sun temples in India, the three well-known ones are Martand in Kashmir, Konarak in Orissa and Modhera in Gujarat.

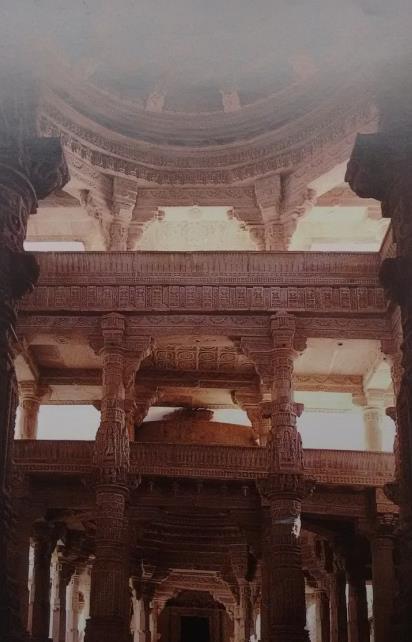

Figure 44

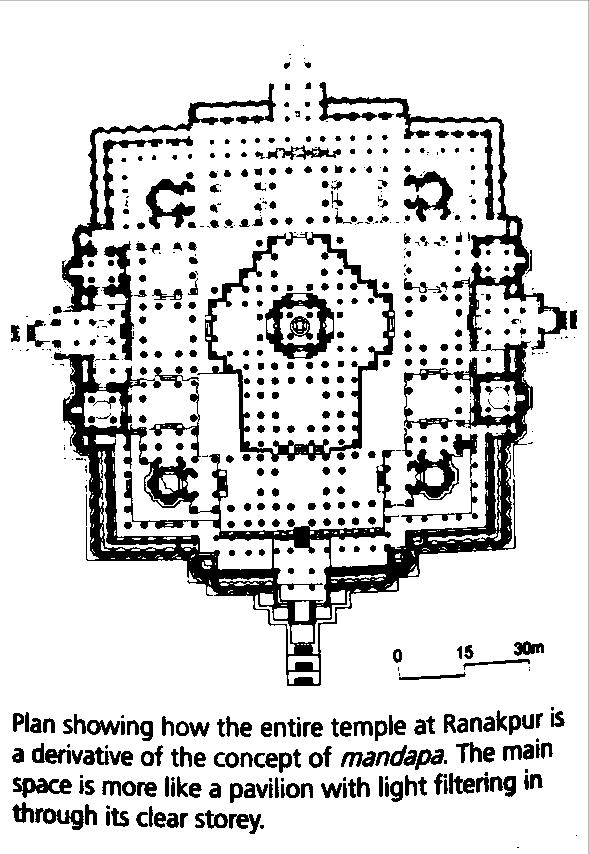

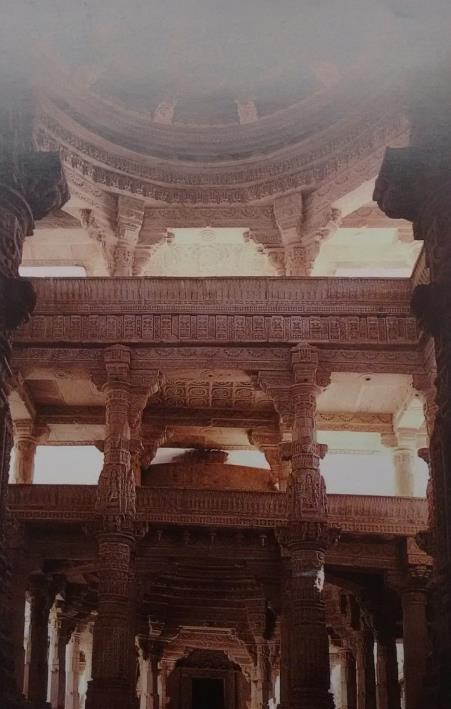

One of the finest examples of religious architecture which captures the essence of divine light is the Jain temple at Ranakpur. This Jain temple built in 1439 AD is structurally engineered by means of using multiple systems of spanning. The entire spatial organisation is a layered complexity of volumetric diversity and uses an extremely large number of columns in the support system. Traditional stone construction with columns, brackets and lintels form the primary system upon which is superimposed a domical construction executed in a corbelled manner with extra brackets. Externally these domes are extended vertically to give a shikara form. The dull white marble in the interior adds to the ambient light.

The key mode of drawing light into the main spaces is clerestory, which made use of the trabeated system and various corbelled dome roofs. A number of small courtyards also contribute to the quality of light within the precinct. The complexity of spatial configuration as layered by four hundred and twenty columns and interposed by light is a manifestation of the finest order. The courtyards add to the drama of light and shade. The essence of design for light is captured through the clerestory, both through the column-beam and column-dome articulation.

“The view from the entrance through the succession of open halls with sunlight entering their clerestories and penetrating the suffused atmosphere as a strong beam illuminating a success of individual elements on the shafts of the

great, many faceted piers is unsurpassed in all of India.” – Christopher Tadgel.

Figure 45 & 46

Exquisitely carved elements make up the Ranakpur temple. However, as far as the spatial organisation is concerned, it is a combination of simple pavilions and courtyards. The complexity is achieved by the manner of putting together the basic unit.

Stone carving details on the Rankpur column at Ranijikichatrian, give character, association meaning to the simple pavilion.

Figure 47 & 48

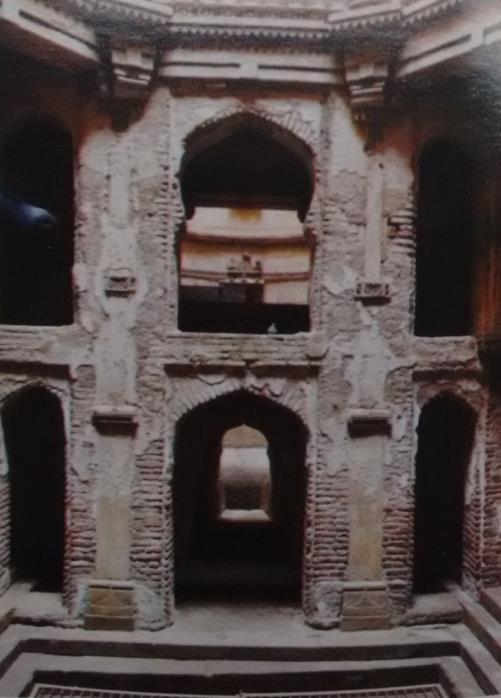

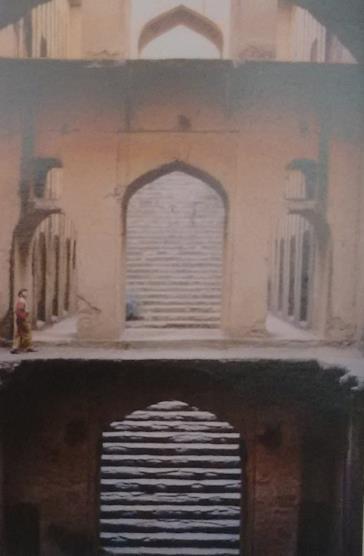

The step-wells in the north western parts of India, particularly in Gujarat and Rajasthan, are unique, both in conception as well as manifestation. Besides several other engaging aspects of design, light emerges as a very important part of this form of subterranean architecture. Structural articulation, determines a rhythmic movement as one reaches for water several floors below the ground level. The modulation so determined also generated voids in the roof to allow light to reach the bottom of the well. Though based on the idea of capturing top light, the structures here are not looking for divine light. The step-well at Adalaj near Ahmedabad is taken up for discussion here in order to demonstrate the virtues and values enshrined in the making of such places. The step-well, vav in the local language, is a deep and narrow space providing access to the water some twenty metres below, with three entrances at one end and three at the other, beyond the sunken tank a draw well, though connected with the main structure, is not accessible from the main stairway.

Broad flights of steps go down to reach the well, this descending space is interspersed with a series of platforms providing partial cover to the stairway. Besides their structural role, these platforms in the days gone by were also utilised by travellers as resting places, cool and ventilated subterranean spaces. These spaces, along with the beautifully articulated and exquisitely carved columns, beams and brackets, are dramatically illuminated by shafts of light that pour in through the openings at the

floor level. This dramatic experience of light and space is heightened as one looks at the linear spatial configuration through the structural elements and the alternating light and shadow sequences. Even while walking down, one is constantly made aware of the play of light on the horizontal and the vertical elements created by the galleries and the platforms. The most outstanding aspect is the variation in the mood and quality of light one experiences as morning changes to evening and summer turns to winter. This dramatic occurrence is further enhanced by the exquisitely carved elements.

“The idea of transition can be explained best through the architecture of stepwells. The sequence of change from outside to inside, from land to water, from the brilliance of tropical light to the muted ambience of the interior, and from the extreme heat of the outside to the pleasant coolness of the inside can all be experiences here. These changing realms show what transition is all about.” – Jain.

Figure 49 & 50

Adalaj Step-well, near Ahmedabad, showing quality of light in relation to space and architectural elements.

5.5 STRUCTURE

Whether it is conceptual or manifest, in nature or architecture, structure is the base for all form, sometimes manifesting in its purest form, but often concealed behind other considerations. Implicitly so or explicitly, it is intrinsic and integral to the act of building. Even an abstract idea has a sense of structure inherently woven into it, though a completely faithful expression of it may not always be present. However, the essence of structure manifests itself in all architecture. It is the structure which holds

the building together.

Irrespective of scale, although more so for larger spans and enclosures, the philosophy and science of structure has played a very important role in generating both space and form. It is useful to look at the various attitudes that finally manifest themselves in built forms. However, history clearly shows how structure has played a key role in generating spaces and forms that display significantly consequential aspects of architecture.

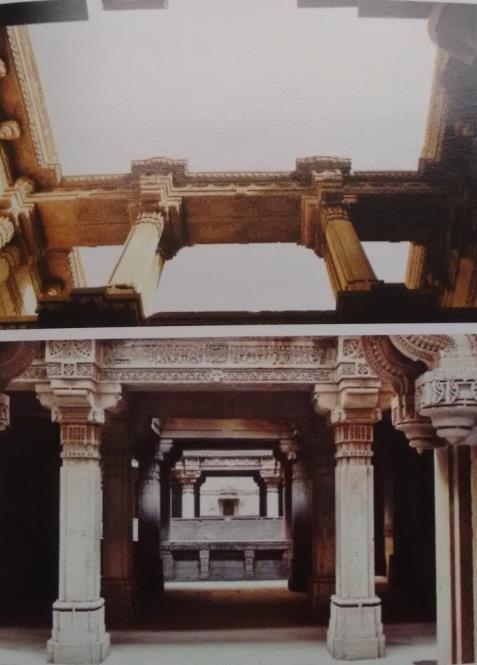

In Indian architecture a system of construction uses a minimum number of elements to resolve spatial expectations. Here through the creation of a phrase that is uses in repetition, multiple variations in the scale and size of spaces is achieved. This can be seen in several mandapas and pavilions. This principle has been emerging and manifesting itself right across India, with regional variations, for more than two thousand years.

The construction systems could be trabeated or arcuated depending upon the constraints of the space-time context. Large spaces, as well as small spaces, could be built using the same modular unit; a single unit defined the smallest space and the multiplication of units created larger spaces. To achieve large unobstructed spaces, domes could be built on an otherwise beam-and-column configuration by leaving out a single column from each of the grids. This could create a space four times the size of

one modular space, and eliminate four columns at the same time, resulting in nine times of the size of a single unit. The elaboration of columns, beams and brackets or arches fluctuated between absolutely minimal ones on the one hand and extremely ornate ones on the other. The construction system so evolved responded to the needs of different religious structures like temples, mandapas and mosques. It served well in the construction of secular buildings too, like royal pavilions, palaces and houses.

One interesting example of structural resolution in a very specific earthretention context can be seen in parts of western India. Architecture generated to serve specific needs such as accessing and storing of water goes back to the Harappa perios, or even earlier. Systems of step-wells (vavs) and tanks (kunds) started evolving around the fifth to the sixth centuries AD. These systems came to be much refined and saw maturity between the eleventh and the sixteenth centuries. The step-well at Adalaj, near Ahmedabad was built towards the end of the fifteenth century AD.

“Since vavs are subterranean and have deep vertical surfaces on their long sides, the problem of earth retention is even more critical that in the kunds. Vertical earth

Figure 51-53

surfaces could not be retained either by stone pitching, as in the case with kunds, or by a retaining wall. Shoring and shuttering were the most scientific ways of holding the earth in its place. This generated a complex system of shores and struts in stones. These elements primarily serve this function, although they carry the galleries and platforms also. Obviously, the beams work as shores coming under compression due to the horizontal thrust of the earth. The manner in which this problem has been technologically resolved is most ingenious. Since the structural system required for this purpose could be suitably spaced, courts open to the sky were created between the covered galleries. This brought in a beautiful cadence of diffused light, right from the bottom of the vav. The quality of this cascading flow of light is unsurpassed beauty. Deep within the ground, the cool spaces, lit as it were with fairy tale lighting, are evocative of nothing but dreams.” - Kulbhushan Jain.

Further: “The trabeated system of construction is elaborate, carved and decorated with geometric as well as figurative motifs. Square pillars with rebated corners have a broader base and capitals with brackets to support the beams. These structural elements perform the dual function of retaining the side earth and supporting the galleries at various levels. However, at places they function purely as struts and shores and do not carry any platforms or galleries. The entire construction is in buffcoloured sandstone adding harmony and unity to this well-proportioned structure. The carved relief work on the structural elements, wall surfaces and parapets adds to the richness, though the merit of this architecture does not depend on its decoration.”

Adalaj Stepwell, Ahmedabad

aaa

Figure 54 & 55

Figure 56

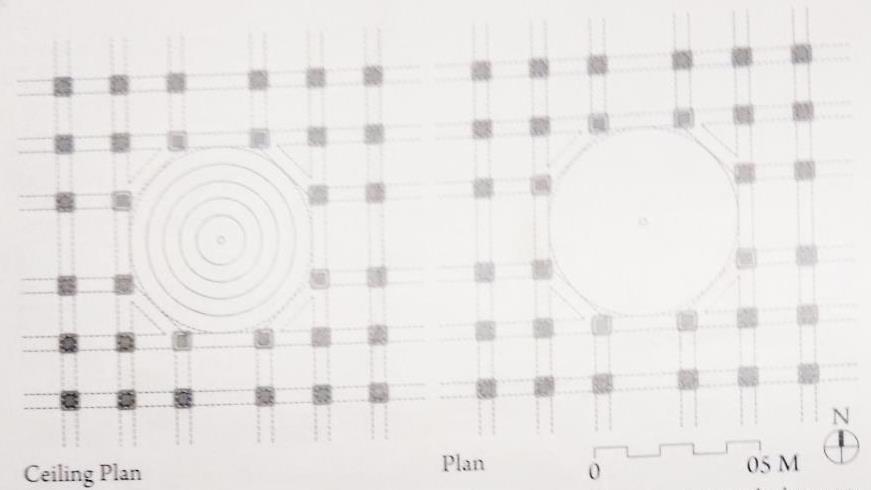

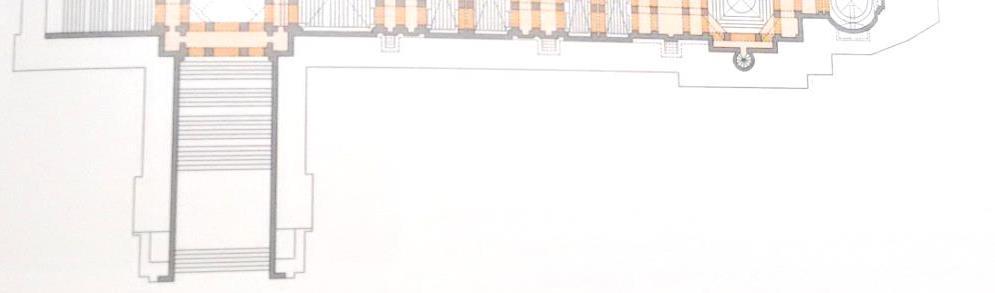

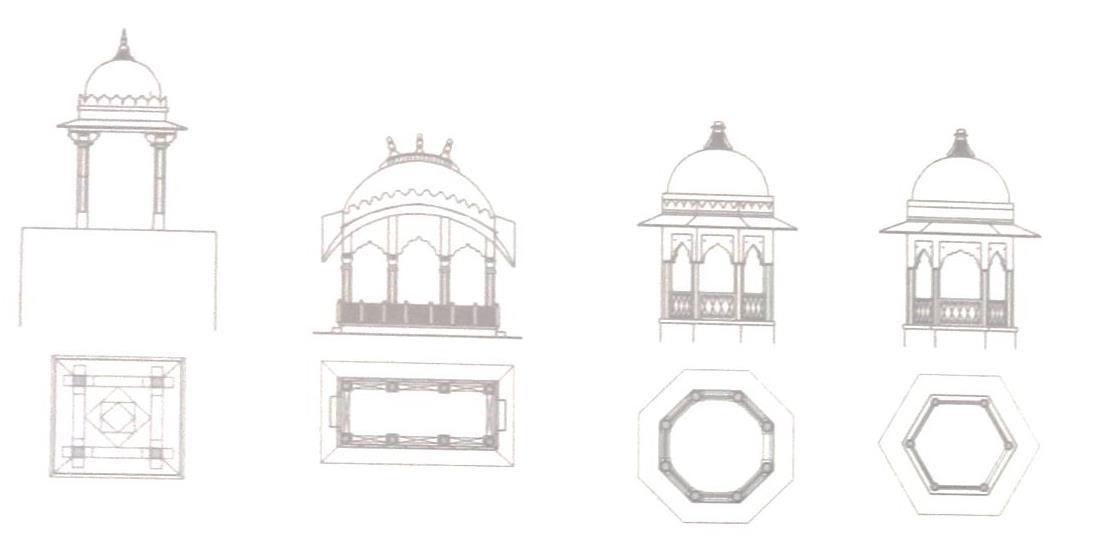

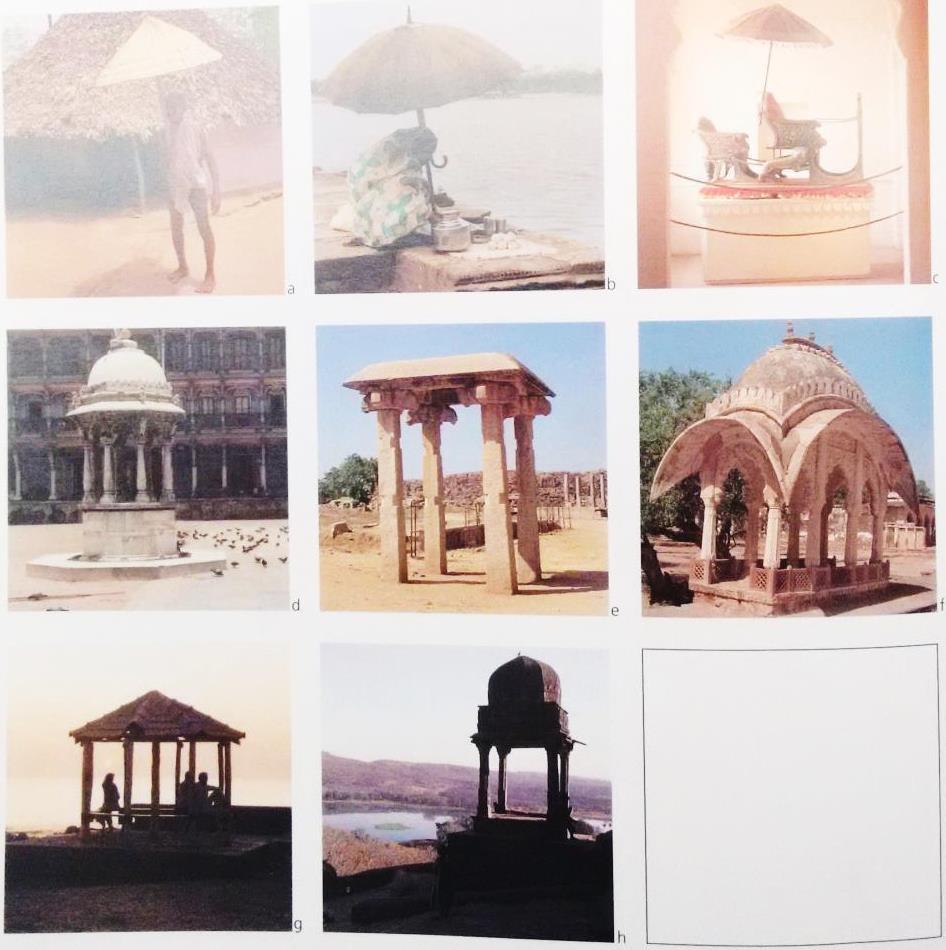

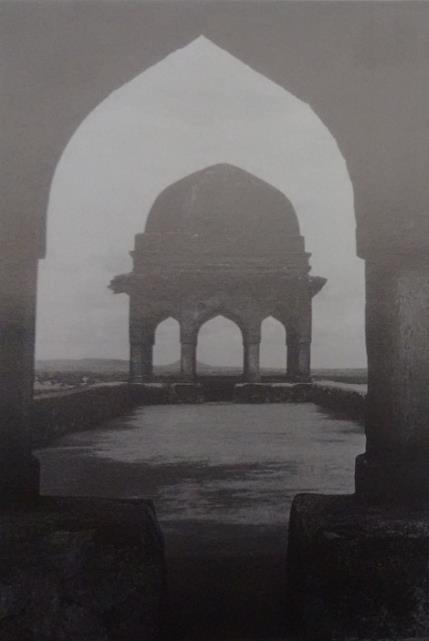

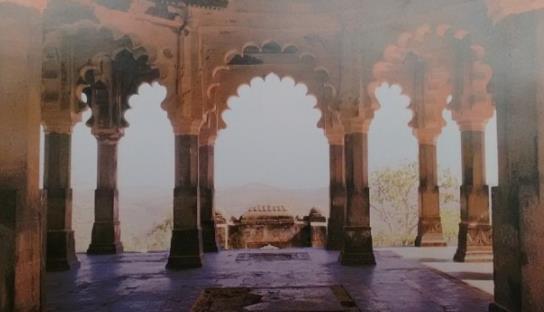

5.6 PAVILIONS

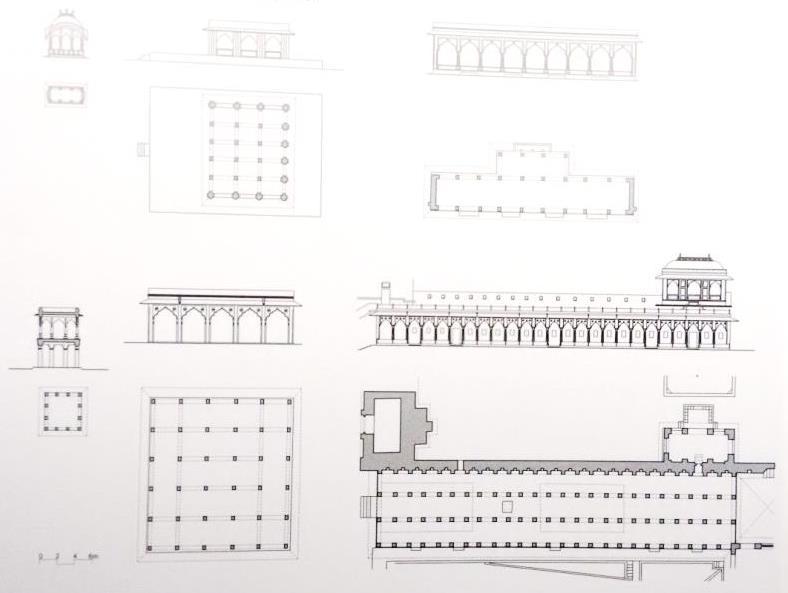

Pavilions, with their various names and forms, have an undeniable presence in Indian architecture. They came into being by multiplying very simple spatial units in modules. Consisting of four columns and a roof, they may be trabeated or arcuated depending upon where and when they were built. Irrespective of the style and construction method, their essence is the same. Mandapas and baradaris are some outstanding examples of spaces created to provide well-articulated shelters for gatherings or for pleasure. Mandapas find a wider expression and are often used as arrival or gathering spaces in temples, like a sabhamandapa. Pleasure pavilions known as baradaris have an extremely sophisticated form in Rajput and Mughal complexes. In their spatial essences, a mandapa and a baradari is one configuration serving different purposes. The most important aspect of this kind of space is that it offers a simultaneous experience of the inside and the outside. Several regional variations of this form can be found across the country.

A pavilion in its most rudimentary form comprising four poles and a roof is perhaps the oldest surviving form of constructed architecture. The genesis of this shelter goes back several thousand years when raw wood and thatch were used in the first human efforts to build. Since then, this element has remained an important feature of architecture, particularly in India. The essence of this form remained unaltered even when the construction materials changed. Stone as raw slabs, twigs, bamboo, banana plants, clay pots, large leaves and cloth have all been used to create this basic form.

The essence of this spatial unit lies in its modular character and therefor in its potential for multiplication – in contiguity or as independent units organised in certain proximity. However, there is no fixed pattern to it. Several permutations and combinations are observed in its application. It is a built space, yet open. It defines and yet extends boundaries and can exist itself or be part of a group. Despite regional and temporal variations, the power of its manifestation has remained unaffected. It conveys the idea of shelter, but does not enclose; it is built and has a presence, yet it is transparent and ethereal.

Figure 57

Figure 58

A unique feature of this space is it versatility, both in terms of function as well as adaptability to regional construction techniques. Its greatest virtue is, of course, its ability to grow to make larger spaces by a simple add-on process. While on the one hand its strength lies in its universal character, it adds to its meaning through thematic manifestations. The shelter-related themes include functions celebrating life, religious rituals, pleasure and death. Not only is these but, its essence independent of caste, creed and class. Marble pavilions in the royal complexes and the peasant shelters in the countryside reflect the same spirit of architecture. The difference lies in the details. However, the underlying commonality of form emerges from the response to the quality of comfort in particular climatic conditions. It is clear that such open shelters served best during summer evenings in arid regions, or even in the warm humid regions, allowing a free flow of fresh air. As a matter of fact, in many parts of India,

during some seasons, people could carry out their activities in such spaces almost for the entire day.

Figure 59-63

With the passage of time, specific designs were developed for certain purposes and the pavilion form evolved in a few distinct categories. The mandapa, being associated with temples, has very definite connotations. It constitutes the front space of a temple. Open on all its sides and with a very distinctive roof, mandapas demonstrate a very evolved form of the pavilion. It is intended to be used for gatherings. A three-storey mandapa at the Ranakpur temple is one of the best examples. However, mandapas can exist independently and yet serve some templerelated activity. Most of the South Indian temples are dotted with mandaps, at times with a 1000 pillars.

The medieval city of Vijayanagara (Hampi) demonstrates an amazing array of pavilion structures built in local granite. Set amidst granite boulders, these structures blend well and at the same time stand out clearly on account of their form. Built with single-piece granite pillars, capitals, beams and roof slabs, these units demonstrate perfect geometric articulation and how modular units can be multiplied. From a single module to a large cluster of these units, the spaces so formed serve religious as well as secular functions. The architecture of these pavilions evokes a feeling of lightness, as well as connectedness. It identifies and defines a focus. It gives the opportunity to divide space in landscapes, and becomes a reference point with a position in water or on a hilltop.

The long processional avenue in front of the great Virupaksha temple at Hampi is lined with several mandapas. The avenue terminates at the foot of a hill where a great Nandi is seatedin a mandapa. Figure 64-67

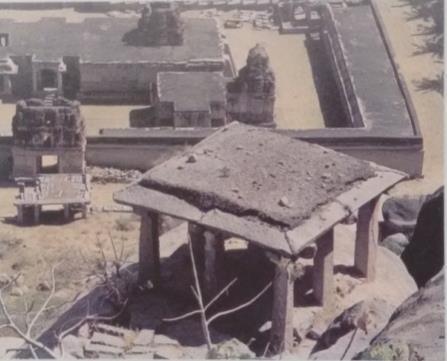

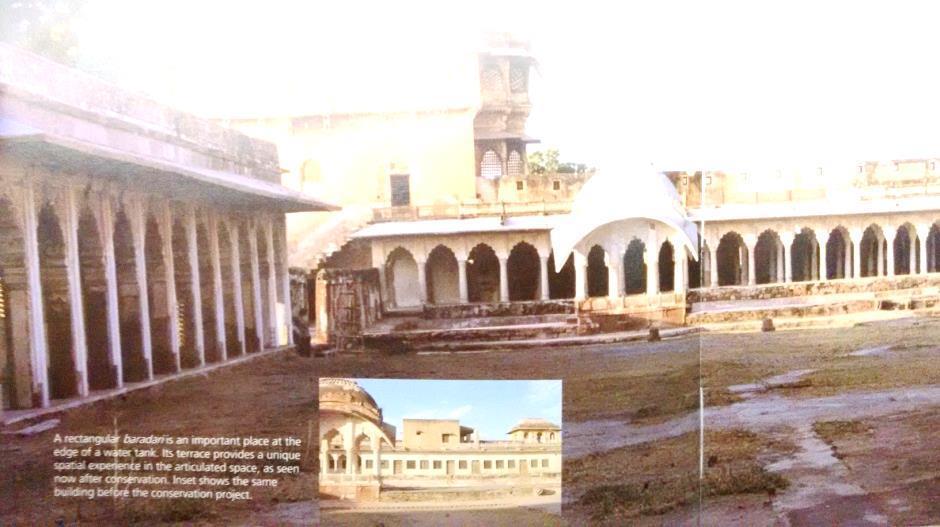

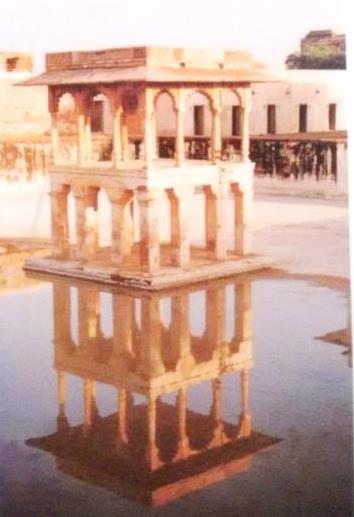

Another version of pavilion structures called the baradari is fairly common in the north-western parts of India. It is a beautiful example of how the basic form has responded to the various construction methods and styles of building. Every royal complex has to have a baradari, often more than one. The use of the baradaris as pleasure pavilions is clearly understandable since they are invariably located in gardens, or on high points or along water tanks and lakes. These structures are so articulated with the landscape and the spatial order of a building complex as to provide the most strategic location for a good view, fresh air and general comfort.

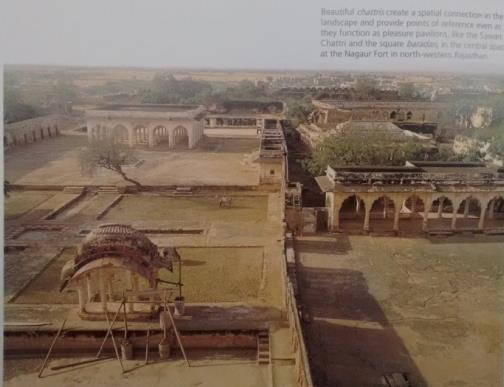

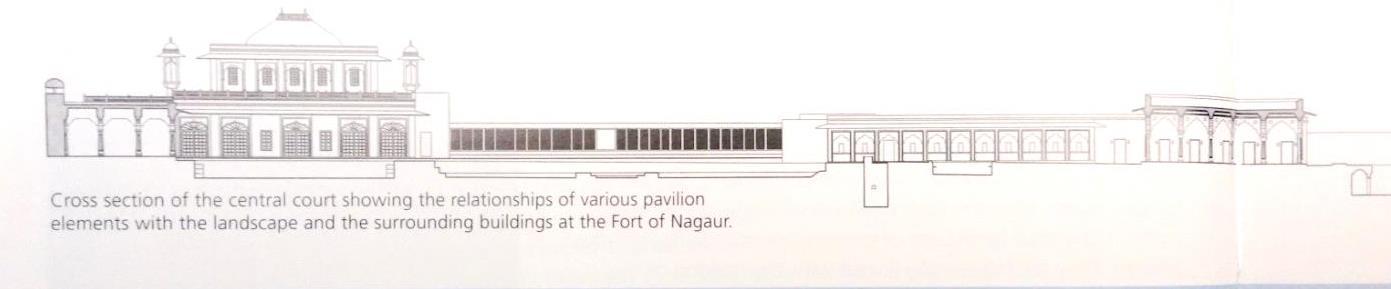

These semi-open structures heightened the human experience of the architectural richness while enhancing the ambience of pleasure and luxury. Ahhichtrangarh, the fort at Nagaur, boasts of many such pavilions which have become focal points in the total landscape of gardens, ponds, walkways and palaces. They are intrinsically linked with the making of the recreation spaces. The rectangular baradari, the square baradari, the savanchattris and the Jal Mahal pavilions contribute in constructing links in the total complex, visual as well as physical.

Beautiful chhatris create a spatial connection in the landscape and provide points of reference even as they function as pleasure pavilions, like the SawanChattri and the square baradari, in the central space at the Nagaaur Fort in north western Rajasthan.

Figure 68 & 69

Figure 70 - 72

Amongst all the forms of pavilion structures, the baradaris have demonstrated the broadest range of stylistic expression. These structures were easily adopted by the various ruling classes who modified them to suit their personal aesthetic sensibilities while retaining their essential form. While the pillared halls, open on the sides, continued to be the basis of all design, it is the spanning systems which changed to suit the preferences of the builders. Stone brackets and beams were common with the Rajput builders while many Islamic rulers adopted pointed arches. Pavilions, particularly the baradari, started emerging as one of the key spaces influenced by this cross-cultural interaction.

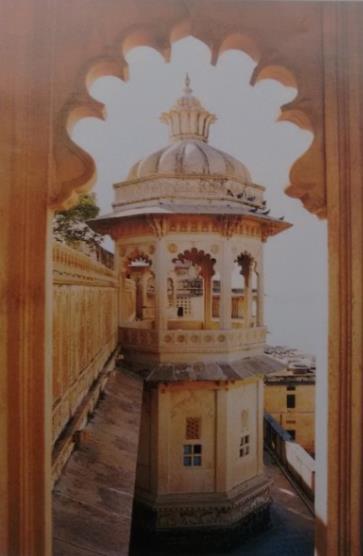

Another variation in the themes which define a pavilion is the large cupola-like structure called a chattri in the north-western parts of India. The structure is polygonal or circular in plan and has a domical roof. Amongst all pavilion forms, the chattri is the most versatile one. Its use is related not only to one kind of activity, but several. From pleasure pavilion to roadside shelter, from decorative cupola on a roof corner to a cenotaph, a chattri can easily serve several purposes, depending on its scale. This extremely adaptable element is space, but equally it is a complete form. One of the finest examples is the 32 pillared chattri at Ranthambor in eastern Rajasthan.

Chattris are often grouped in clusters, particularly when used as cenotaphs or as memorials. However, since they are a complete form by themselves, unlike the other pavilion forms, they cannot be interconnected form by themselves, unlike the other pavilion forms. Also, chattris generally have only peripheral supports allowing columnless space. This naturally brings about dimensional limitations. There are a few exceptions where larger chattris have been constructed using inner columns to achieve the required size. With the adoption of the Bengal hut roof, rectangular chattris have also been constructed. Chattris are not only part of the landscape; they are often seen atop mosques and cenotaphs, palaces, havelis and even houses. They are the culmination of a building, its silhouette made transparent. On terraces once again they become places for enjoying the view and the breeze.

Rani Rupmati pavilion at Mandu

Figure 73 - 77

Small and large pavilions dot the terraces of the Udaipur City Palace. Removed from the bustle of the palace, they afford intimacy as well as the spectacular views of the city, the lake and surrounding environs. Apart from being individual buildings, chattris become design elements in a larger form, combinations of which give the character of a building as in the tomb of Sikandar.

5.7 THE IN-BETWEEN REALM

In architecture, the in-between refers to the realm of actual physical change that finds expression linking two areas with distinct environmental qualities. The most significant if these is the connection between ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ through spatial inbetween zones. This transition deals with the movement from one situation to another; from one set of ‘space-light’ values to another. An extended area of transition carries through it the feeling of both, the external and the internal, gradually changing from one to another. There are examples where the entire experience revolves around the idea of transition, like in the step-wells where ‘land-water’ transition is often expressed through architectural drama.

Besides its life-sustaining function, water has great symbolic and ritualistic significance in Indian culture. The simple act of reaching water is important and is never abrupt. An extended area of transition provides a gradual changing experience. Its elaborateness and emphatic expression can be seen in the making of traditional ghats, kunds, pavilions, step-wells (vavs) and other structures connected to water. While ghats create special places along the banks of rivers, lakes or the sea, kunds demonstrate a keen consideration for architecture; they are not just pits or ponds filled with water. Vavs are rich, elaborate and eventful, creating an architectural narrative around water elements.

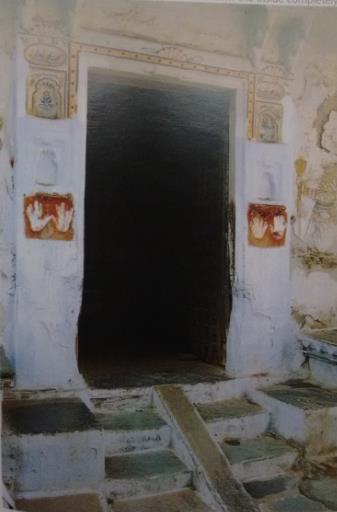

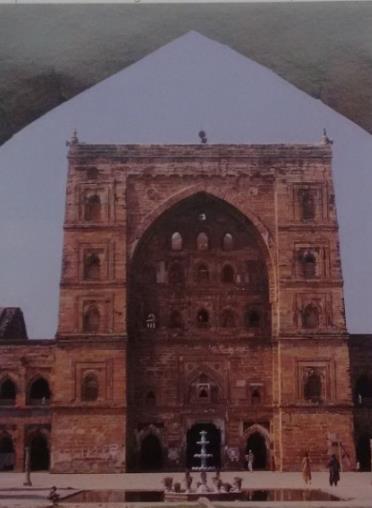

The most important transitional relationship between two distinct realms is expressed through entrances. Whether it is the entrance to a city through a fort wall with defence, or a hierarchical sequence of spatial layers with a series of in-between realms, incorporating symbolic as well as functional values, transition remains the most significant aspect. The complexity of transition as an architectural element varies from community to community. In many cultures, entrances are intentionally indirect in order to achieve greater privacy. On the other hand, there are examples where a single door can be the total and only link between the inside and the outside. Apart from the symbolism and rituals associated with entrances are thresholds, these inbetween realms have a special meaning in Indian architecture, both religious and secular. The threshold, expressive of transition, has always received special attention from the past. Even today, ceremonies on all important occasions include a special event connected with the threshold, which in many cases is decorated and even worshipped every day. Sometimes, these transition realms or gateways become larger than the space within, just as the Buland Darwaza is much larger than any structure in the mosque complex. The gopurams of South India are often larger than the main temple itself.

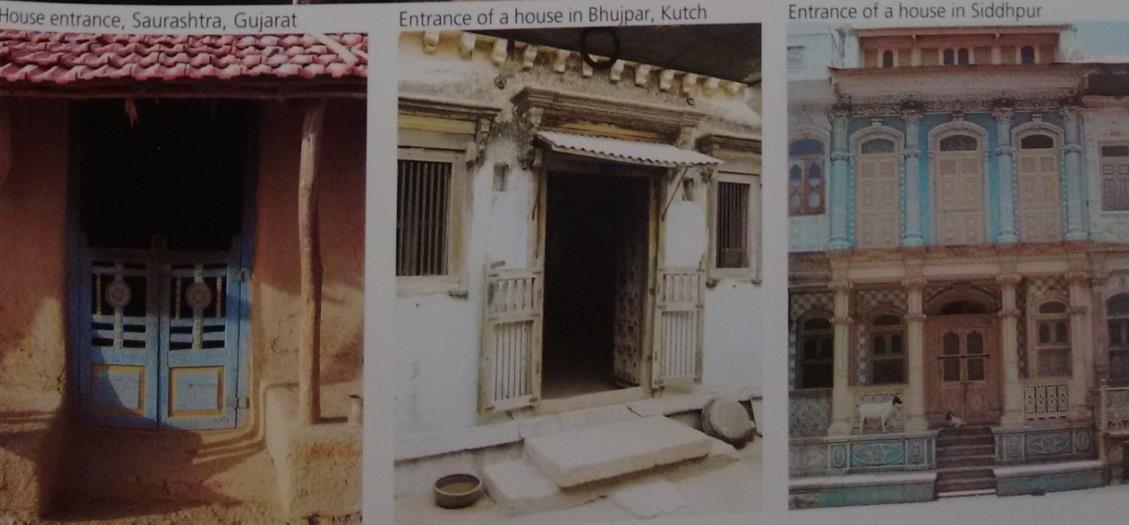

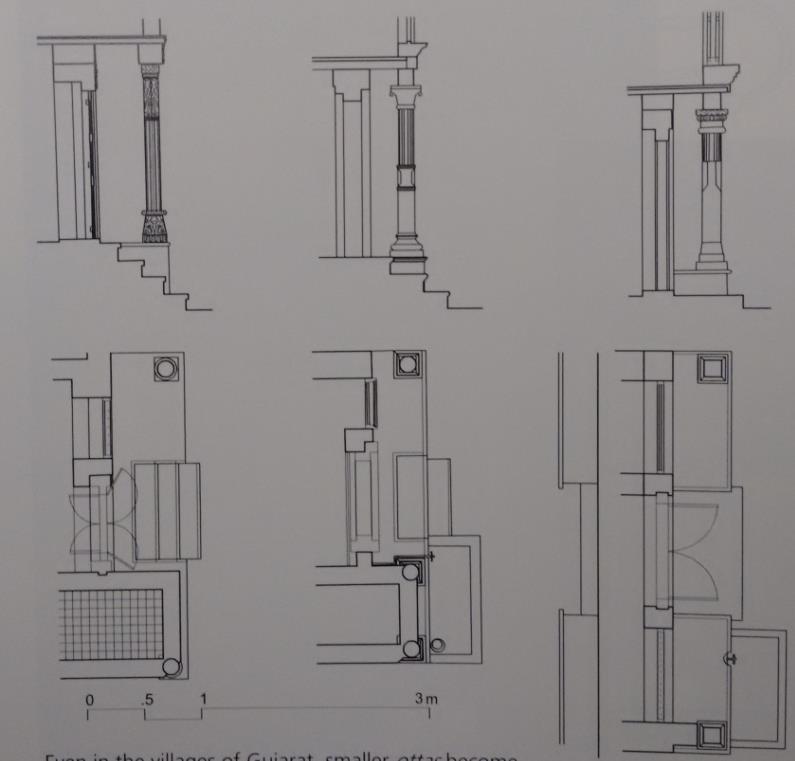

Connecting a house to a street has been an intriguing aspect of architecture from time immemorial. Transitional areas not only include the threshold, but also the steps and platforms beyond it, all of which are carefully articulated into one entity. These areas are not only places for arrival or departure but also prove the spill-over of the activities of the house. Their dimensions and elaborateness depend on local cultural factors which differ from place to place. Typically, in Gujarat, a small verandah-like space with steps and, at times, pillars supporting the upper floor, are common. This element is called the ‘otla’. It allows for both privacy as well as participation. In Rajasthan, stone steps often at right angles of the house, lead to a small platform.The connection of the built form with the land on which it rests became another area for

the expression of transition. Plinths became the mode of this transition. They also became large platforms encouraging social interaction. This expression was particularly enhanced in religious structures as well as buildings of public importance. The plinth reinforced the importance of that particular institution. A gradual building up of steps leading to the main space was then articulated in an elaborate manner.

Figure 86 - 88

While providing a link with the entrance, the connection of the entire periphery of a building with the outside is also an important aspect of transition. This vital link is established through windows, galleries, balconies and verandahs. Here also, climate has a definite role of play. In hot dry areas, building peripheries are closed to the outside almost completely. Often, in such situations, a window is not just a fenestration, but a place offering a visual transition between inside and outside. It is made elaborately and is related to the daily activities of the inhabitants. A zharookha is such a place and elements like these play a vital role in articulating facades. It is not a thin demarcation of the inside and outside but a three dimensional space.

While entrances deal with one kind of relationship and control movement from outside to inside, cloisters and verandahs around the courtyards or along the periphery of the building are functional areas serving the cultural and climatic needs of a place. Such semi-enclosed areas cater to diverse family activities. These transitional zones have a special role in modulating scale. Moving inward from external brightness and vastness, these elements and places help to control the change to darker and smaller internal spaces. These controlled, yet open spaces help avoid abrupt change.

Section through the entrance of the City Palace, Udaipur. The various levels of transition through plinths, zharookhas, verandahs and even pavilions negotiating the skyline are seen here.

Figure 89 - 92

Figure 93 - 98