Critical Habitat of Rice’s

Whales

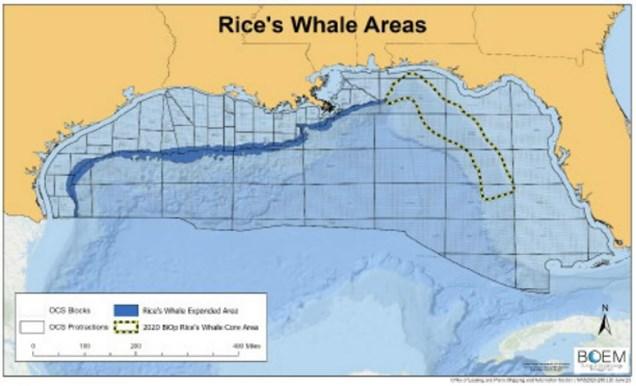

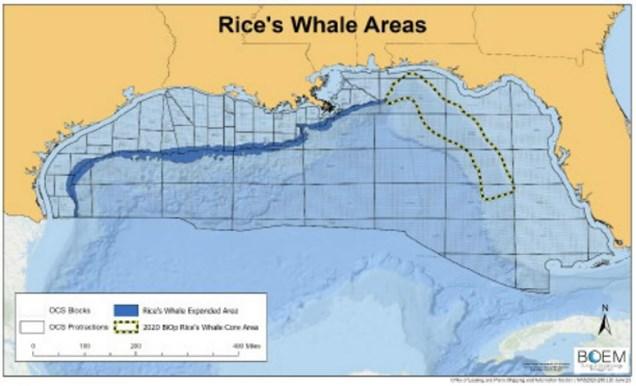

The habitat of the Rice’s whale is only beginning to be understood. The whale is most frequently spotted where the continental shelf breaks, at water depths between 100 m - 400 m from Mobile Bay, Alabama, south to just past Tampa, Florida. However, that general location is being revised as new evidence is found.

Two studies, one published in 2022 and one 2024, reported finding acoustic evidence of

2 Melissa Soldevilla, et al., Rice’s whales in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico: call variation and occurrence beyond the known core habitat, Endangered Species Research, Vol. 48: 155-174 (July 28, 2022) (hereinafter 2022 Acoustic Study); Melissa S. Soldevilla, et al., Rice’s whale occurrence in the western Gulf of Mexico from passive acoustic recordings, Marine Mammal Science, (Feb. 13, 2024).

3 2022 Acoustic Study, p. 158.

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Rice’s whales off the coast of Louisiana and as far south as off Tampico, Mexico, respectively. The whales were identified by their unique “long-moan call” – three notes each lasting between 20 – 40 seconds and involving downward pitch changes. The pitch moves from approximately 150 Hz down to 103 Hz, which is towards the lowest note on a piano (110 Hz is about 2 octaves above the lowest note). According to those reports, the long-moan calls were captured 24.7 percent of the time by the recorder offshore of Corpus Christi. Notably, the recordings of the whale off the coast of Mexico are the first evidence of the whale in Mexican waters.

The authors of the studies say the recordings do not indicate whether there are more Rice’s whales than thought or whether they travel farther than previously known. This information complicates efforts to define its habitat, which in 2015 was waters 100 m – 300 m deep south from Pensacola to just south of Tampa (see Figure 3), and in 2019 was expanded up to Mobile Bay (see Figure 2). Now the habitat could be waters 100 m to 400 m from just south of Tampa all the way around the Gulf to the border of Texas and Mexico (see Figure 4).

The unique Rice’s whale call helps scientists find the species, as the whale is not seen often. It is not known for splashy behavior, no fluke flaps or wild breaches. In fact, in 2020 NMFS wrote: “little is known about the Gulf of Mexico [Rice’s whales’] life history the life expectancy is unknown …. the age of sexual maturity is not known … they are observed in small groups, pairs or solitary…. No data exist on [its] hearing abilities.”4

What is known is that the female Rice’s whale can be 42 feet long with the male being slightly smaller.

4 NMFS, Biological Opinion on the Federally Regulated Oil and Gas Program Activities in the Gulf of Mexico, pp. 167-168 (March 12, 2020) (hereinafter 2020 BiOp).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Figure 3: 2015 Biologically Important Area of Rice’s Whale. Credit: Erin LaBreque et al., Biologically Important Areas for Cetaceans Within U.S. Waters – Gulf of Mexico Region.

Figure 4. Credit: Federal District Court for the Western Dist. Louisiana, 2023.

To feed, it gulps large amounts of water and pushes the water out through bony plates known as baleen, keeping the food. It eats diel migrating species, like squid and crustaceans, that move down the water column during the day and up near the surface at night. This means the whale spends an estimated 70 percent of its time at depths of 15 m or less: 47 percent at this depth during daylight hours, 88 percent at night.5

Vessel Restrictions for the North Atlantic Right Whale

An estimated 360 endangered NorthAtlantic right whales live offshore from Florida to Canada and can be 52 ft. long. According to NMFS, “vessels of nearly any size can injure or kill a right whale.”

NMFS limits vessels of 65 ft or longer to 10 knots during certain times of year within Seasonal Management Areas.Additionally, Massachusetts requires vessels of any size to travel at less than 10 knots in Cape Cod Bay at specific times of year.

Figure 5. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Issues for Whales in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a busy waterway. When considering how to designate Rice’s whale critical habitat, NMFS found many activities could require consultation under the ESA to get an incidental take statement (the name of the permit under the ESA). Those activities include oil and gas production, renewable energy, military activities, and fishery management. NMFS also could have included mariculture/aquaculture as almost all of the Aquaculture Opportunity Areas identified by NMFS in the Gulf appear to occur within the 100-400 m area. Shipping is another factor affecting whales in the Gulf of Mexico but does not require consultation for the most part.

According to a 2022 stock assessment of the Rice’s whale, the mean number of Rice’s whales likely to die or suffer serious injury from human causes each year – oil spill, vessel strike, or marine debris, for example – exceeds the rate the species can withstand to order to reach its optimum sustainable population.6

5 2020 BiOp, p. 540.

6 NMFS, U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments 2022, p. 119 (June 2023) (hereinafter 2022 Stock Assessment) (referring to potential biological removal (PBR)).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Shipping

Shipping can be a hazard for the Rice’s whale. Notably, the top three water ports in the United States based on tonnage are in the Gulf of Mexico – starting with Houston – and six others make the top 13.7 A commercial ship’s maximum draft can be 15 meters below the surface. Thus, Rice’s whales’ habit of being near the surface at night puts them at risk. While one Rice’s whale died from a vessel strike in 2009, according to NMFS’s 2022 Stock Assessment, data on ship strikes are hard to come by. One source estimates that 98 to 99.6 percent of whale carcasses in the Gulf of Mexico are not recovered.8

Oil and Gas Development

Petroleum is another essential part of the Gulf of Mexico economy that also poses a threat to the whale. The Gulf of Mexico is key to the United States’ oil and gas production and refining capacity (see Figure 6). The federal agency in charge of regulating energy production in the Gulf of Mexico, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) of the Department of the Interior, consulted with NMFS about potential impacts to listed species from its oil and gas leasing program. NMFS issued a biological opinion (BiOp) in 2020. It found that the program posed jeopardy to Rice’s whales (still called Bryde’s whales at the time). That is a big deal – not many BiOps find that a federal project could lead to the extinction of a species.

Gulf of Mexico Oil and Natural Gas Resources and Infrastructure

• 15% of U.S. crude oil

• 5% of U.S. natural gas

• 47% of U.S. petroleum refining capacity

• 51% of U.S. natural gas processing plant capacity

Figure 6. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (June 1, 2023).

In its jeopardy BiOp NMFS concluded that: over the course of the 50-year proposed action, the entire small, isolated [sic] of Gulf of Mexico Bryde’s whales is expected to experience a reduction in fitness from combined stressors resulting from the proposed action.9

NMFS found that activities related to oil production were likely to adversely affect the whale, such as seismic testing, vessel traffic and noise, oil spills, and marine debris. However, at the time of the BiOp the whale was known to occur only in the eastern Gulf, an area closed to oil leasing at least until July 2032.10 Accordingly, when issuing reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) as required for

7 U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

8 2020 BiOp, p. 544.

9 Id. The leasing program is a multi-step process allowing entities to bid on places to explore and eventually develop oil and natural gas.

10 See Pres. Memo., Memorandum on the Withdrawal of Certain Areas of the United States Outer Continental Shelf from Leasing Disposition (Sept. 8, 2020).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

jeopardy BiOps, NMFS only issued RPAs for oil-related vessels in the Rice’s whale’s core area (see Figure 2), such as a 10 knot per hour speed limit.

NMFS placed limits on geological and geophysical (G&G) testing via regulations issued in 2021. G&G testing is sometimes known as seismic testing where ships tow deep penetration air guns that shoot sound waves into the seabed to locate good spots for oil production (see Figure 7). In 2020 BOEM acoustic modeling predicted that the Rice’s whale population could experience 12 injurycausing exposures (at 183 dB) each year for 50 years from seismic testing conducted at the exploration phase of oil development, and an additional 451 sound impacts annually of such intensity as to affect their behavior.11 According to a NMFS report, baleen whales (such as Rice’s whales) incur permanent hearing loss from noise between 183-219 dB.12

Not everyone agrees. In response to a proposed G&G regulation, the American Petroleum Institute commented jointly with other ocean development industries, summarized by NMFS as follows:

“there is no scientific evidence that geophysical survey activities have caused adverse consequences to marine mammal stocks or populations, and that there are no known instances of injury to individual marine mammals as a result of such surveys, stating that similar surveys have been occurring for years without significant impacts.”13

In response, NMFS referred to the NationalAcademies of Sciences’2017 statement that although “no scientific studies have conclusively demonstrated a link between exposure to sound and adverse effects on a marine mammal population,” that was because “such impacts are very difficult to demonstrate, not

11 2020 NOAA BiOp, p. 411.

12 NMFS, 2018 Revision to: Technical Guidance for Assessing the Effects of Anthropogenic Sound on Marine Mammal Hearing (Version 2.0) (Apr. 2018). That same report states that dolphins’ threshold for permanent hearing loss is 155-202 dB. (A gunshot on land 100 feet away is 140 dB).

13 NMFS, Final Regulation: Taking Marine Mammals Incidental to Geophysical Surveys Related to Oil and Gas Activities in the Gulf of Mexico, 86 Fed. Reg. 5322, 5333 (Jan. 19, 2021) (hereinafter NMFS Final Regulation). These regulations were re-evaluated by NMFS, 88 Fed. Reg. 916 (Jan. 5, 2023), and were reissued unchanged based on slightly different analyses. 89 Fed. Reg. 31488 (April 24, 2024).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Figure 7. Credit: BOEM

because they do not exist. ”14 Also, BOEM has found that seismic noise was likely to harm cetaceans. In its NEPA review for G&G testing, BOEM found that a marine mammal’s immediate death was “not likely to be a direct result of seismic noise” but that “sublethal injurious effects are possible and may, over time, result in the eventual death of the individual(s).”15 Additionally, even when noise does not cause injury, it can impede whales’ communication.

The G&G regulations allow each permit holder’s activities to harm no more than one-third the population of a marine mammal species.16 Multiple permits are issued each year. To illustrate, since 2022, NMFS has authorized approximately 40 separate 1-year incidental take permits (known as a Letter of Authorization (LOA)) to multiple companies to conduct seismic testing in the Gulf of Mexico. Three of those LOAs were anticipated to harass 2 Rice’s whales (3.9 percent of the population) each and 28.7 percent, 31.8 percent, and 32.8 percent of the Gulf population of endangered sperm whales, respectively.17 It is not clear what the cumulative impact of such exposures may be.

Conservation Challenges

All this to say that the Gulf of Mexico is a busy place with competing priorities. For example, in 2021 groups petitioned NMFS to impose a 10 knot speed limit in the identified core area of the Rice’s whale at the time (see Figure 2). The groups also wanted a ban on crossing the areas at night, visual observers on board, and notification and reporting requirements. NMFS denied the petition after receiving approximately 75,000 comments, saying it was premature because critical habitat had not yet been determined nor a vessel risk assessment conducted.18

Several environmental groups challenged the 2020 BiOp, claiming NMFS underestimated the risk of harm to protected species and that the RPAs and the limits on incidental take were inadequate.

14 NMFS Final Regulation, at p. 5333.

15 NFMS Final Regulation, at p. 5333 (quoting BOEM 2017 Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for G&G Testing).

16NMFS Final Regulation, at p. 5367.

17 See, e.g. 89 Fed. Reg. 17419 (March 11, 2024) (authorizing Shell Offshore, Inc. to harass two Rice’s whales among other marine mammals, including 31.8% of sperm whales); 88 Fed. Reg. 23403 (April 17, 2023) (authorizing WesternGeco to harass two Rice’s whales among other marine mammals, including 28.7% of sperm whales); 87 Fed. Reg. 43243 (July 20, 2022) (authorizing TGSNOPEC Geophysical Co. to harass of two Rice’s whales among other marine mammals, including 32.8% of sperm whales).

18 See 88 Fed. Reg. 20846 (April, 7, 2023) (seeking public comments on petition by Natural Resources Defense Council, Healthy Gulf, Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Earthjustice, and New England Aquarium), NOAA Bulletin, NOAA Fisheries Denies Petition to Establish a Mandatory Speed Limit and Other Vessel-Related Mitigation Measures to Protect Endangered Rice’s Whales in the Gulf of Mexico (Oct. 27, 2023) (announcing denial of petition).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Figure 8: Sperm whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries.

The lawsuit was filed in federal court in Maryland (based on NMFS’s headquarters) which issued a stay, pausing the action while NMFS prepared a new BiOp, as requested by BOEM.19 The court issued the stay without objection by the parties including the American Petroleum Institute (API) and other industry groups who joined the suit out of concern that NMFS would not represent their interests. As part of the consent to stay, BOEM agreed to exclude portions of the Gulf from oil development to protect Rice’s whales.

The next day theAPI and others, including some U.S. Senators, joined the State of Louisiana in a lawsuit filed in Louisiana against BOEM, arguing that BOEM’s changes to the pending lease sale, which were partially in response to the 2022 acoustic study, were contrary to law.20 The changes included: withdrawing 6,000,000 acres from the lease sale – where the Gulf waters were between 100 and 400 m; imposing a 10 knot speed limit; and limiting nighttime travel. The federal court in Louisiana found that BOEM lacked the authority to modify the project at that stage, and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.21 The lease sale at issue was held December 20, 2023, without the modifications.

In January 2024 the federal court in Maryland lifted its stay, and litigation regarding the 2020 BiOp continues. However, legislation proposed in the House of Representatives would prevent a BiOp from being issued until the NationalAcademies of Sciences completes a habitat assessment of the Rice’s Whale.22 The bill does not authorize or appropriate any funding for that study, however. Thus, the bill could function as an implicit amendment of the ESAby freezing the obligation of NMFS to issue a BiOp upon request of a federal agency.

Conclusion

No other whale species in the United States faces the issues of the Rice’s whale, perhaps the least known whale in the country. The species likely is close to extinction with a best guess of 51 individuals, yet it must co-exist in an area key to U.S. shipping and oil production.

Eight years ago a list of whales in the Gulf of Mexico would not have named Rice’s whales. In that short time, NMFS scientists have protected the species under the Endangered Species Act, identified them as a genetically distinct species, and begun to understand their core habitat and behavior. Much of this information is due to the whale’s dispiritedly named “long-moan call.”

As much as things have changed for the Rice’s whale, there is much still to do. NMFS has not named Rice’s whale critical habitat which could impact diverse projects such as oil and gas development, mariculture farms, fishery management, and perhaps shipping. That designation likely will lead to litigation about what efforts are needed to protect the whale’s imperiled population and at what cost.

Any such litigation will involve the ESA. The Endangered Species Act requires that all federal agen-

19 Sierra Club v. National Marine Fisheries Service, No. 20-CV-3060, 2021 WL 4704842 (D. Md. May 24, 2021) (the plaintiffs include Sierra Club, Center for Biological Diversity, Friends of the Earth, and Turtle Island Restoration Network).

20 Louisiana v. Haaland, 2023 WL 6450134, *1 (W.D. La. Sept. 21, 2023).

21 Louisiana v. Haaland, 86 F. 4th 663 (5th Cir. 2023).

22 See H.R. 6008 (118th) (also, critical habitat must be designated with additional conditions, and the BiOp process would be changed).

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

cies must “carry[] out programs for the conservation of endangered species … and [take] such actions necessary to insure that actions authorized, funded, or carried out by them do not jeopardize the continued existence of endangered species….”23 The U.S. Supreme Court has held that this duty applies even when the economic expenses are high.

In that 1978 case, TVA v. Hill, the Court considered a federal action against the agency’s obligation to protect an endangered species.24 The federal action was a $100,000,000 dam that was “virtually completed,” and the endangered species was a 3-inch fish called a snail darter, believed not to exist anywhere else. The U.S. Supreme Court said “the explicit provisions of the Endangered Species Act” (as quoted above) required the permanent halting of the dam which would “eradicate the known population.”25 While that may seem an extreme result, the Court found that Congress had rejected a draft version of the ESA that would require federal agencies to carry out only programs that “are practicable” to protect species:

The plain intent of Congress in enacting this statute was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost.26

The snail darters were relocated to allow the dam’s operation over two years later, a less practical alternative when the protected species is a whale.

Presumably, once more is known about the Rice’s whale, its habitat can be managed in a way consistent with the economic drivers of the Gulf of Mexico while still promoting the recovery of the species. After all, in 2022 snail darters were removed from the endangered species list, in part because their habitat was found to be larger than originally thought.

23 Pub. L. No 93-205, § 7, codified with slight nonsubstantive changes at 16 U.S.C. § 1536(a).

24TVA v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978).

25 TVA v. Hill, 437 U.S. at 172-73.

26 TVA v. Hill, 437 U.S. at 183.

VOL. 2, ISS. 1 MAY/JUNE 2024

Figure 9: Rice’s whale seen April 11, 2024, 55 nm off the coast of Corpus Christi. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Paul Nagelkirk.