Harvard Public Health Review

Fall 2011

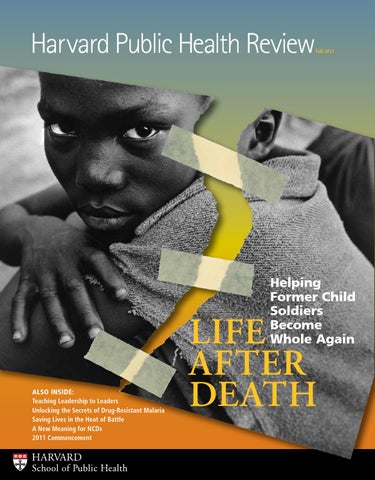

Helping Former Child Soldiers Become Whole Again

Also Inside: Teaching Leadership to Leaders Unlocking the Secrets of Drug-Resistant Malaria Saving Lives in the Heat of Battle A New Meaning for NCDs 2011 Commencement

HARVARD

School of Public Health

Life after Death

Dean’s Message

A Broader View of Global Security

T

he year 2001 saw not only the horrors of 9/11 and the anthrax attacks, but also the establishment of the UN Commission on Human Security. In its report to the General Assembly, the commission wrote that human security “means protecting people from critical and pervasive threats and situations, building on their strengths and aspirations. It also means creating systems that give people the building blocks of survival, dignity, and livelihood.” In a world of rapid global change, that is the timeless mission of public health. Indeed, during the past decade, the health agenda has moved from the exclusive domain of medical and public health practitioners to take center stage among many different groups of experts as they address some of the most pressing issues of our time. We now understand that: • Good health is not just the result of economic development—it is one of the conditions for economic development to occur at all. Much of why some nations develop faster than others is that their people enjoy better health.

2

Harvard Public Health Review

The absence of good health, generated by the slow-burning persistence of huge inequities around the world, is one of the major causes of global insecurity. This issue of the Review offers a number of stories demonstrating Harvard School of Public Health’s broader sense of what constitutes global health security. The cover story on Theresa Betancourt, who for nearly two decades has worked with children traumatized by war, illustrates how HSPH researchers are trying to help promote resilience and healing in these young people. The School’s National Preparedness Leadership Initiative, co-led by Lenny Marcus and David Gergen, demonstrates that enlightened leadership in times of disaster is a quality that can actually be taught. Other stories on HSPH’s impact on malaria, military medicine, TB, and health inequities underscore how health is at the heart of global security.

The absence of good health, generated by the slow-burning persistence of huge inequities around the world, is one of the major causes of global insecurity. The injustice represented by the millions of unnecessary deaths from preventable causes breeds social discontent that may eventually lead to resentment and extremism. It is by improving health, addressing fundamental inequities, and preventing threats to well-being that we in public health can be leaders in bringing about true global security.

Julio Frenk Dean of the Faculty and T & G Angelopoulos Professor of Public Health and International Development, Harvard School of Public Health

Kent Dayton/HSPH

• Good health is key for national security and economic stability. Infectious disease pandemics can potentially kill thousands, disable millions, and disrupt entire economies. Investments in epidemiologic surveillance and response are crucial to controlling threats—whether natural or man-made.

• Good health underlies democratic governance and the realization of human rights. A comprehensive definition of health security includes access to health care as well as protection against the economic consequences of disease—so that no one goes broke for getting sick.

Harvard Public Health Review

Fall 2011

18 Life after Death Theresa Betancourt has made it her mission to understand resilience and healing in former child soldiers and war-affected youth. 2 Dean’s Message Also in this Issue A broader view of global security 14 4 Frontlines 14 Teaching Leadership to 10 Philanthropic Impact Leaders 45 Alumni News Helping seasoned professionals handle unprecedented disasters 47 Faculty News 26 Unlocking the Secrets of Drug Resistance in Malaria Parasites New gene search tool opens “endless possibilities”

26

29 A Public Health Perspective for Physicians Commonwealth Fellows 32 Returning Home A plan to thwart killer TB 36 Saving Lives in the Heat of Battle Delivering military medicine in Afghanistan 40 Looking Back, Looking Ahead Commencement 2011

Image Credits: Cover, 14-year-old child soldier from Sierra Leone ©Stuart Freedman/ PANOS; This page top and center, Kent Dayton/HSPH; below, Comstock/Getty Images

42 Strengthening Health Systems to Address “New Challenge Diseases” Reframing the familiar public health acronym “NCD”

47 Bookshelf 48 In Memoriam 49 Continuing Professional Education Calendar

Clarification The Spring/Summer 2011 issue of the Review included an article by HSPH professor emeritus Bernard Lown, “Waging Peace, Saving Lives,” which described Lown’s lessons and observations as an antinuclear activist. A photo caption incorrectly identified Lown as the “founder of Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.” In fact, Lown was the co-founder of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, along with American physicians Herb Abrams, Eric Chivian, and Jim Muller, and with Soviet physicians Evgueni Chazov, Leonid Ilyin, and Mikhail Kuzin. In addition, the article states that IPPNW was founded in 1981; the correct year is 1980.

front lines

Listen Up: Kids Get Fewer Ear Infections in Smoke-Free Homes

I

Attorney General SPEAKS ON YOUTH VIOLENCE AT HSPH U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder advocated a public health approach to addressing youth violence at a May 6 Forum webcast. The event was moderated by Jay Winsten, Frank Stanton Director of the Center for Health Communication at HSPH. Watch

n the first study to show the public health benefits to children of the increase in smoke-free homes across the U.S., researchers from HSPH and Ireland’s Research Institute for a Tobacco Free Society quantified a decline over the last 13 years in middle ear infections among children. The study attributes the drop—which reverses a long-term upward trend—to the rise in U.S. households that have adopted voluntary no-smoking rules: from 45 percent in 1993 to 86 percent in 2006. Lead author Hillel Alpert, research scientist in HSPH’s

online at http://hsph.me/holder-forum.

Organized chaos: tracking cellular crowds

pull as they migrate through the human body—even while they’re moving cooperatively in the same intended direction. A new study by HSPH and the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia found that cell groups migrating toward a task—say, healing a wound, creating an embryo, or forming a malignant tumor—are far less orderly than once thought. Understanding how and why cells behave as they do in large groups may lead to ways to control or interrupt diseases such as cancer that

Department of Society, Human Development, and Health, says that if parents avoid smoking at home, they can “protect their children from [ear infections], the most common cause of visits to physicians and hospitals for medical care.” A seminal paper published by the School’s Dimitrios Trichopoulos in 1981 was among the first to establish a link between secondhand smoke and lung cancer.

involve abnormal cell migration.

Learn More Online Visit the Review Online at http://hsph.me/frontlines for links to press releases, news reports, videos, and the original research studies behind these stories.

4

Harvard Public Health Review

Clockwise from top: Kent Dayton/HSPH; Ebby May/Getty Images; Shaw Nielsen, illustration

Like racers jostling for position, groups of cells push and

The Heat is On A new study by researchers at HSPH and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health looked at how heat waves—predicted to increase in number and intensity with global climate change—may affect city dwellers. Currently, according to American Red Cross statistics, heat waves cause more deaths than all other weather events combined. (In just one week in 1995, a summer heat wave in Chicago caused nearly 700 excess deaths.) The HSPH/ Johns Hopkins research, led by Francesca Dominici, HSPH professor of biostatistics and associate dean for information technology, estimated that in the years 2081–2100, Chicago could see 166 to 2,217 additional deaths annually—“a profound impact,” according to Dominici.

Clinton and Sebelius Visit HSPH-affiliated Clinics in Tanzania

H

SPH faculty are engaged in various research and training initiatives in Tanzania, with the ultimate aim of improving maternal and child health and reducing the risk of infectious diseases such as HIV, TB, and malaria. On June 12, 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton visited the Buguruni Health Center in Tanzania. That facility, associated with HSPH, offers reproductive and child health services. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius attended the opening of the Mnazi Mmoja Center for Excellence in HIV Care and Education in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, on July 22. The Center, for which HSPH Dean Julio Frenk helped lay the foundation stone earlier this year, provides a general outpatient clinic with services for family planning, reproductive and child health, HIV care and treatment, and tuberculosis care. It also serves as a site for training in HIV management to develop nationally recognized leaders in the field, and to conduct research to advance knowledge related to management of HIV/AIDS. Funding for the Center comes from the United States via the School’s President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program in Tanzania, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and an agreement with Management Development for Health (MDH), an independent organization in Tanzania established with support from HSPH, that aims to sustain and expand existing public health service programs.

Women’s Height Declining in Developing Countries U.S. Department of State

Over the last 40 years, adult women’s height in economically deprived countries has either declined or stalled. The findings come from a new HSPH study that tracked this key indicator of the health and wellbeing of a population, and a predictor of children’s chances for survival. The declines are thought to reflect poor nutrition, exposure to infections, and other environmental factors that may stunt or hamper children’s growth. The study, whose lead author was S.V. Subramanian, HSPH professor of population health and geography, tracked women’s height in 54 countries between 1994 and 2008.

Fall 2011

5

front lines Seeing Patients through the Lens of Impoverished Lives Day after day, the medical histories of the young patients Nadine Burke, MPH ’02, treated at her clinic in San Francisco’s impoverished Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood followed strikingly similar patterns. Childhoods marred by stress and trauma were followed

Study Reveals Racial Differences in Stress Levels

A

n HSPH team led by research fellow

Michelle Sternthal found that African-Americans

by a host of adult physical ailments such as asthma, scabies, and weight

and U.S.-born Hispanics

problems. As described in a March 21 profile in The New Yorker, Burke

suffer higher stress levels

realized one day, after treating a teenage mother: “What if [the patient’s]

than whites and foreign-

anxiety wasn’t merely an emotional side effect of her difficult life, but the

born Hispanics—and that

central issue affecting her health?” Today, the Bayview Child Health Center addresses the physiological effects of patients’ childhood traumas—and Burke hopes to eventually develop a protocol much like those that doctors use for treating patients with cancer and other diseases.

this stress contributes to these groups’ frequently poorer health compared to whites. The investigators studied 3,000+ Chicago blacks, whites, and Hispanics ages 18 and older. According to senior author David R. Williams, HSPH’s Florence and Laura Norman Professor of Public Health, “This study underscores the importance of safety-net programs—unemployment benefits, cash assistance,

Governor Patrick Describes Next Phase of Health Care Reform

housing, child care, and transportation benefits

Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick spoke about the next phase

to low-income working

of Massachusetts health care reform—controlling costs and improv-

families—to promote the

ing quality—at an April 28 Forum event. The governor’s speech was

economic well-being and

Professor of the Practice of Public Health. Watch online at http://hsph.me/patrick-forum.

6

Harvard Public Health Review

the health of families faced with high levels of stress.”

Ned Brown/HSPH

followed by an expert panel moderated by John McDonough, HSPH

Offthe Cuff

W “

Bill Hanage, Associate Professor of Epidemiology

hy are we seeing so many deadly new forms of E. coli in our food?

Bacteria are a bit like a Mr. Potato Head®. You have the core DNA—which is the potato—and then onto

that are stuck all kinds of other genes that help it adapt to its niche. In bacteria, the promiscuous interchange of genes is happening all the time, so new combinations constantly emerge. And our globalized food chain helps new combinations of genes to reach and colonize new niches. People often say, ‘Bacteria are a primitive life-form.’ No, they’re not. They’ve been around longer than we have and they’ll be around after we leave. It’s estimated that the number of bacterial cells on the planet is five times 1030—that’s a 5 followed by 30 zeroes. To

put that in context, that’s more than the number of stars in the known universe. So in terms of our knowledge of bacteria, we haven’t scraped the tip of the iceberg, not even the thin sheen of ice melt in the midday sun on the top of the iceberg. We’ve seen maybe the top few layers of molecules about to evaporate. Causing foodborne disease is not the primary function of E. coli. It’s just that we tend to notice that quality in them. We’re humans, Kent Dayton/HSPH

we’re self-centered, and what happens to us is the most important thing in the world. Learn More Online

”

Visit the Review Online at http://hsph.me/frontlines for links to press releases, news reports, videos, and the original research studies behind these stories.

Fall 2011

7

front lines

Why IS Health Care Reform So Elusive? Interview with John McDonough Q: W hat are the biggest myths and misconceptions about the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act? A: A significant number of people believe that there are death panels in the law. And many believe that when the big expansions and the individual mandate take effect in 2014, they are going to have to give up their employer-sponsored insurance and buy individual coverage on their own. Both assumptions are absolutely untrue. John McDonough, HSPH Professor of the Practice of Public Health, was a senior adviser on the U.S. Senate committee responsible for developing

Q: H ow does American public opinion break down on health care reform? A: A bout half of the public—mainly Republicans—says that the law should either be completely repealed or substantially repealed. About half—mainly Democrats—says the law should be kept as is or strengthened.

the Patient Protection and Affordable

Q: Does that suggest Americans have different core beliefs about the issue?

Care Act, the landmark health care

A: There is a broad shared sense—actually, bipartisan—that we spend much more on health care services than we would need to if we had an efficient, effective health care system. The difference is how to do that. For example, Democrats wanted to reduce Medicare spending by $450 billion over ten years and use those proceeds to pay for expanding coverage to the uninsured. Republicans don’t mind cutting Medicare by $450 billion—but they wanted to use the money for tax cuts. It’s not an argument over facts or data. It’s an argument, fundamentally, over values.

reform plan that President Barack Obama signed into law in March 2010. A former Massachusetts state legislator and executive director of the advocacy group Health Care for All, McDonough recently spoke with the Review about the revolutionary

Q: How did health care spending spin out of control?

Security Act of 1935 and the Medicare

A: If you go back to before the 1980s and look internationally at health spending as a percentage of gross national product, you find that the United States is expensive—but bunched among the leading nations. Not until the early 1980s did we become an outlier. We took off and grew at a much faster clip than all of the other industrialized countries. A: That may be because, in the 1980s, the U.S. embraced with gusto this ethos that market competition would fix our health care system. At the state and federal levels, we abandoned different kinds of regulation and instead embraced “competition.” The idea was that it would drive down costs and create better value. But it didn’t.

and Medicaid Act of 1965. His new book is Inside National Health Reform. See page 47 for more information.

8

Harvard Public Health Review

Kent Dayton/HSPH

law, which he compares to the Social

An early draft of the bill that would become the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Q: In your mind, what’s the best health care system in the world? A: My best of all possible worlds is something like the French system. In terms of public satisfaction, the French are near the top. They spend only about 10 percent of their national income on health care services—very reasonable, by international standards. It’s one of the most effective and efficient and high-quality systems in the world. Everybody is covered. There is complete choice of providers. And even though France spends a lot less money per person than we do, they have more physicians, more hospitals, and more hospital beds per capita. Like many other national health care systems that work, the French system is coherent and cohesive in terms of its financing, workforce planning, access to care, and accountability. All those parts work together toward the common goal of delivering quality health care. Q: How will we pay for the new national law? A: The law gets paid mostly through two buckets. One bucket is ten years of changes in the Medicare program, which is going to generate about $450 billion in savings to the Federal Treasury. For example, the hospital industry agreed to give up $155 billion in revenue that they would otherwise obtain from the Medicare program—they figured that if insurance coverage went up in the U.S., they would eventually recoup the loss. Same deal with the home health industry and others. The other bucket is new “ … in the 1980s, the U.S. taxes and assessments on higher-income individuals, new fees on pharembraced with gusto this ethos maceutical companies and medical device makers, and a fee on insurance companies. that market competition would Q: What’s an especially effective provision in the new law?

REUTERS/Larry Downing

A: One of my favorite provisions in the law is a 10 percent tax on the use of indoor tanning services. When Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid brought out his version of the bill, initially there was no indoor tanning tax. Instead, there was a tax on elective cosmetic surgery that became known as the “Bo-Tax.” It was met with shrieks of anger from many consumers—particularly women—who felt that it was discriminatory, as well as strong opposition from the American Society of Dermatologists. Q: In the final version, the “Bo-Tax” was removed. At the last minute, the Senate substituted a tax on indoor tanning services. In recent years, we’ve seen an explosion in skin cancer diagnoses such as melanoma, especially among women between the ages of 15 and 35. From a public health standpoint, that’s one of the most defensible measures in the law. Thea Singer is a Boston-based science journalist and author.

fix our health care system. At the state and federal levels, we abandoned different kinds of regulation and instead embraced ‘competition.’ The idea was that it would drive down costs and create better value. But it didn’t.” Learn More Online Visit the Review Online at http://hsph.me/frontlines for links to press releases, news reports, videos, and the original research studies behind these stories.

Fall 2011

9

philanthropic impact

A Challenge We Face Together This fall, nearly 500 new students enter HSPH. They come from 44 different countries and 40 U.S. states. Many of them arrive having already accomplished extraordinary things in their careers. They are physicians, professors, scientists, policy analysts, research assistants, medical residents, teachers, and others who see public health as the best way they can make a difference in the world. What better way to welcome them than with the words of Dr. Lakshmi Nayana Vootakuru, who, as student speaker at commencement in May, sent the departing class off with these thoughts: Ellie Starr Public health is about re-imagining this society, to one where education, health, and opportunity are plentiful and access to services is available to those who need it most and can ask for it least. Yes, in this most scientific of fields, firmly rooted in epidemiology and biostatistics, the most salient feature to me is…imagination. Because that is where transformation begins. …Henry David Thoreau said, “This world is but a canvas to our imaginations.” May your imagination give you the vision to create a hundred new realities in every corner of the globe and every frontier of public health.

Imagining a healthier world is a challenge we face together. To everyone who has risen to this challenge—and especially those who have supported our students and contributed to our ambitious goal of tripling financial aid over the next two years—thank you. I can imagine no better way to make a difference than helping committed people whose driving ambition is to make the world a better, safer, more just, and healthier place.

Ellie Starr, Vice Dean for External Relations

Safety Test: Gates Foundation Supports Clinical Trial for Childbirth Checklist

O

f the estimated 130 million births each year around the world, 4 million babies die in the first 28 days of life. Nearly 350,000 of those births result in the mother’s death, 99 percent of them in developing countries. An innovative childbirth safety checklist—a single sheet providing core guidelines to improve safety and health care quality around the time of birth—could have a dramatic impact on making birth safer for mothers and children around the world. Thanks to a $14.1 million, four-year grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, HSPH researchers will test the effectiveness of the World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Childbirth Checklist in reducing deaths and improving outcomes for mothers and infants in 120 hospitals in northern India. A team led by Atul Gawande, associate professor of health policy and management at HSPH and a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and co-principal investigator Jonathan Spector, research associate in health policy and management at HSPH and a neonatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, worked between 2008 and 2010 with the WHO Departments of

10

Harvard Public Health Review

Patient Safety, Reproductive Health and Research, and Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health to develop the checklist. The list is expected to be released later this year. The same team will now conduct a clinical trial in areas of extreme poverty in northern India to evaluate the checklist’s impact. Based on a review of existing protocols and produced in consultation with frontline health workers and policymakers around the globe, the list focuses on the biggest killers of mothers and newborns, such as bleeding, infection, high blood pressure, and asphyxia. The childbirth checklist program is modeled after a similar safe-surgery program pioneered by Gawande that reduced surgery-related deaths and complications by more than onethird at eight pilot sites worldwide. “Checklists can be an important tool for health workers, because the documents help organize both the time and resources needed to save the lives of women and newborns during birth,” says France Donnay, Senior Program Officer for Maternal Health at the Gates Foundation. “The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is pleased to be a part of this effort.”

Kent Dayton/HSPH

Student speaker Lakshmi Nayana Vootakuru

CIFF Grant Supports New Health Leadership Development Program

H

arvard School of Public Health and Harvard Kennedy School of Government (HKS) will launch a unique ministerial health leadership development program next year in collaboration with the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). Designed for ministerial-level leaders mainly from low- and middle-income countries, the program aims to promote health as a cornerstone of economic development, strengthen political leadership in health, and improve health system performance in the ministers’ own countries. The initiative will place special emphasis on innovations in maternal and child health.

day session that covers progress made and lessons learned. CIFF, a philanthropic organization dedicated to improving the lives of children living in poverty in developing countries, is supporting the program with a two-phase, seven-year grant. The grant awarded for the first phase is $4.01 million. The initial cohort of leaders will give priority to countries in sub-Saharan Africa and India, and in future years the program could expand to include leaders from other regions. Serving as the program’s executive director is Michael Sinclair, former Senior Vice President at the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and head of the Foundation’s South Learning from Africa program. In that role he overDistinguished Peers saw key priorities including health An intensive week-long introducleadership development, child health, tory session for participants will maternal mortality, and HIV/AIDS. open the program next June at HKS. Housed within the new Division Customized to address circumof Policy Translation and Leadership stances specific to each participating Development (PTLD) at HSPH, country, the program will focus on the program will carry out one of topics including leadership for transDean Frenk’s priorities: the translaformation, health and development tion of scientific knowledge into priority setting, political strategy, effective policies and actions. “I am and financing. Distinguished former profoundly grateful to CIFF for its ministers and other high-level govern- support of this effort, which will ment leaders will contribute, adding help fulfill one of my goals as dean an interactive “peer learning” dimenby enabling the School to convene sion to the program. HSPH and HKS current global health leaders to drafaculty, along with local institutions, matically improve the health of their will provide in-country technical citizens,” says Dean Frenk. Jamie and leadership support following the Cooper-Hohn, president and CEO Harvard session to assist leaders in of CIFF, says that the foundation’s implementing health systems improve- partnership in this effort “reflects ments. A year after the program, the our appreciation that the policies, ministers will reconvene for a threeprograms, and resources put in place and allocated by government leaders

are key determinants of progress toward reducing the disproportionately high levels of child mortality and morbidity in these regions.” CooperHohn is an alumna of the Kennedy School as well as a member of the HSPH Board of Dean’s Advisors. Improving Health Systems

“This program hopes to provide a strategic framework aimed at substantially improving the health systems of multiple countries. It provides a bridge to exchange key information between global policy scientists, experienced ministerial policy advisers, and senior decision makers from countries engaged in a transformational process,” notes Division director Robert Blendon, a faculty member with joint appointments in the HSPH Department of Health Policy and Management and at HKS. As a joint project of the two schools, the ministerial program also represents a unique opportunity to couple the Kennedy School’s long tradition of public leadership development with HSPH’s focus on transforming health systems. “We are excited to partner with the School of Public Health to create a unique program to improve the health and livelihood of citizens in developing countries by working with high-level leaders,” says HKS Dean David T. Ellwood. “This is a wonderful opportunity to engage with important international leaders who can create positive change for their societies.”

Fall 2011

11

philanthropic impact

A Humanitarian Academy at Hsph

P

lans are underway to create a new Humanitarian Academy at Harvard School of Public Health, the first global center dedicated to training and teaching the next generation of humanitarian leaders. Approximately 240,000 humanitarian workers worldwide provide billions of dollars in services to millions of aid recipients through relief organizations in more than 100 countries. But in contrast to other large professional pursuits, no major academic programs exist to educate humanitarian aid practitioners in the key principles of their field, such as civilian protection, coordinated aid, and service delivery. The Academy will provide leadership training— both for undergraduate and graduate students as well as

son Eric practices emergency medicine and previously worked for AmeriCares at disaster sites in more than 20 countries. All Weintz’s children serve as trustees for the Foundation. “It seems to us that all you have to do is look at the front page every day to see these kinds of crises arising more and more,” says Weintz. “Maybe it’s a drop in the bucket, but we aim to improve the way disaster relief is taught and handled around the world.” The Academy will coordinate the educational and training activities of several University-wide initiatives, including HHI as well as the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights and the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research. It will also convene faculty from around Harvard who

Worldwide, approximately 240,000 humanitarian workers provide billions of dollars in services to millions of aid recipients. The new Humanitarian Academy at HSPH is the first center dedicated to educating these professionals in the key principles of their field.

12

Harvard Public Health Review

are engaged in humanitarian studies. Ultimately, the Academy aims to define a new field in education while gathering a community of academics and experts committed to worldwide humanitarian issues. “Without Fred and his family’s support, much of what we have accomplished would not have been possible,” says Jennifer Leaning, director of the FXB Center and François-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights at HSPH. “Mike VanRooyen, director of HHI, and I are deeply grateful not only for the family’s generous philanthropic support but for their guidance and advice, which has improved our thinking and practice over the years. We are excited to take this important next step in professionalizing humanitarianism.”

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

for leaders from humanitarian organizations—in areas such as human rights, disaster response, and crisis leadership. The Academy will also develop innovative ways to evaluate the effectiveness of humanitarian aid in order to better serve people in times of war, conflict, and disaster. The Academy is supported by $300,000 in initial seed funding from J. Fred Weintz, Jr., through the Harbor Lights Foundation, which he founded in 1980. Weintz, a graduate of Harvard Business School, is a member of the HSPH Leadership Council and longtime supporter of the School. His family has many years of involvement with humanitarian teaching, training, and global fieldwork, at Harvard and beyond. Weintz’s late first wife, Betsy, was a founding donor of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI), and his

Nanoscience and Health: Tiny Technology Raises Big Questions more efficient clean energy alternatives. By 2015, the global market for manufactured goods using nanomaterials is predicted to exceed $1 trillion. Yet the field is still largely unregulated—and scientists are just beginning to understand the possible environmental and public health risks nanoparticles might pose. Panasonic Corporation, one of the Center’s major supporters and industrial partners, gave $300,000 in April to fund HSPH research on nanoscience and environmental health. The company was ranked one of the world’s top 100 most sustainable corporations in 2011 by Corporate Knights, a magazine that focuses on clean capitalism. Demokitrou says that collaborations between the NanoCenter and major nanotechnology companies such as Panasonic represent a “unique opportunity to estabNanoparticles are used in everything from personal electronics to medical devices to food packaging—but their potential risks are still unclear.

T

lish a more sustainable model for industry than we had in the 20th century.”

he year-old Center for Nanotechnology and Nanotoxicology at HSPH (dubbed the NanoCenter) draws on the School’s long history of

studying air particles and their public health impacts. After more than two decades developing methods that have become industry standard for assessing the health effects of exposure to atmospheric particles, HSPH researchers are poised to study the applications and implications of newly engineered nanomaterials and nanotechnology.

Victor Habbick Visions / Photo Researchers, Inc.; Kent Dayton/HSPH

“We now have the ability to generate and manipulate exotic nanostructures nobody ever put on the planet before,” says Philip Demokitrou, assistant professor of aerosol physics in the Department of Environmental Health, who is among the Center’s founding faculty and its director. “But how will these affect biological systems and the environment?” Nanotechnology—the science and engineering of particles less than 100 nanometers wide (or 1/1,000th the diameter of a human hair), for use in everything from personal electronics to medical devices to food packaging—has grown dramatically in the past several

Philip Demokritou, assistant professor of aerosol physics in the Department of Environmental Health, and director of the Center for Nanotechnology and Nanotoxicology at HSPH

Historically, public health investigations have tended to uncover environmental health disasters, such as the pervasive toxic effects of asbestos or PCBs, decades after the damage has been done. Linking research to industry through the Center can help companies establish parameters for safer product development before new materials ever reach the marketplace. As Demokitrou says, “I can’t think of a better way to safeguard

years. Widely considered to be the industrial revolu-

public health.”

tion of the 21st century, the field has the potential to

Learn more about the NanoCenter at www.hsph.harvard.edu/nano.

help develop solutions for improved drug delivery and

Philanthropic Impact stories written and compiled by Rachel Johnson, marketing and communications coordinator. Fall 2011

13

Leadership Development

The National Preparedness Leadership Initiative teaches seasoned professionals how to handle unprecedented disasters.

14

Harvard Public Health Review

Teaching Leadership to Leaders A

© Ho New / Reuters, Kent Dayton/HSPH

t the World Trade Center on 9/11, the New York Fire Department set up a command center at the bottom of World Trade Center One. The supervisors had a vertical view of the disaster—and based on that information, they sent firefighters rushing into the building to help with evacuation. By contrast, the New York police dispatched a helicopter to hover near where the planes hit—a horizontal view. From that perspective, it was clear that girders were red hot and about to melt, and that the building NPLI co-director Leonard Marcus (left) and faculty member Barry Dorn would soon collapse. With that information, the NYPD ordered all police to evacuate. That day, 23 New York police died and more than 320 New York firefighters lost their lives. This tragic anecdote frames a key lesson at a unique joint program run by Harvard School of Public Health and the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS): the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative, or NPLI. The initiative blends academic theory with practical insights from the field. In the case of the 9/11 attacks, the lesson is known as the “cone in the cube” quandary. Observed through a hole on the side of a box (or building), the cone looks like a triangle. Observed through a hole in the top, it looks like a circle. The point is that different responders with different expertise and missions may perceive emergencies differently—but need to glean each other’s perspectives to smoothly choreograph their efforts. Bad leadership is a public health risk

Co-directed by Leonard Marcus, lecturer on public health practice at HSPH, and David Gergen, director of the Center for Public Leadership at HKS, NPLI is grounded in the idea that U.S. leaders continued Fall 2011

15

have much to learn about managing large-scale disasters, both natural and man-made. One of the singular aspects of NPLI is that its faculty have observed leadership close-up during such signal events as the Deepwater Horizon spill, Hurricane Katrina, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and the H1N1 pandemic response. As public health risks grow ever more complex—with terrorist threats, emerging infections, globalization of

“ In preparedness, “ time is your ally. In response, time “ is your enemy. “ The longer it takes you to respond and get it right, the more likely you are to fail.” —Leonard Marcus

“In NPLI, we don’t teach management, we don’t teach budgeting, we don’t teach supervision in the classic sense,” explains Marcus. “We teach leadership—because in a crisis, bad leadership is a public health risk.” Meta-Leadership

The “meta” in “meta-leadership” means reaching above and beyond one’s scope of authority to forge ties across disciplines and bureaucracies.

the food supply, and climate change and natural disasters—leaders need different skills than they did in the past. Some 350 individuals have taken NPLI’s intensive on-campus executive education course, and more than 4,000 have participated in shorter city-level summits. Armed with new skills and a broader perspective, graduates return to high-impact jobs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), state and local health departments, the Departments of Defense and of Homeland Security,

16

Harvard Public Health Review

the Federal Emergency Management Authority, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and health ministries of other nations. The mainstay of the program is an on-campus course, during which students learn the principles of “metaleadership.” Marcus and NPLI faculty member Barry Dorn, associate director of HSPH’s Program for Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, coined the term after analyzing the actions of leaders in unprecedented emergency situations.

Once the concept was captured in a phrase, says Marcus, more questions arose: “How do you describe it? How do you teach it? And how do you ensure that someone can actually do it?” He and Dorn distilled five teachable dimensions of meta-leadership. (See box: The Five Dimensions of Meta-Leadership.) NPLI’s hands-on approach to researching crisis leadership yields valuable insights, which are immediately incorporated into the meta-

Left to right: ©Carlos Barria/Reuters, Jessica Rinaldi/Reuters, © Danny Moloshok/Reuters

NPLI’s instructors teach lessons gleaned from recent national disasters. From left to right: the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, mass vaccination for the H1N1 influenza pandemic, and airport screening to avert terrorism.

leadership training curriculum. For example, “In preparedness, time is your ally. In response, time is your enemy. The longer it takes you to respond and get it right, the more likely you are to fail,” says Marcus. “A quick assessment that is close to the mark and moves the process forward is better than a slow, though more accurate, response that comes too late to make a difference.”

cials had long feared: the first flu pandemic in 40 years—and in this case, the same subtype of the virus behind the devastating 1918 flu. As the epidemic unfolded, Richard Besser, acting director of the CDC, found himself remembering lessons he had learned at NPLI. In fact, recalls Besser—now a visiting fellow at HSPH, as well as chief health and medical editor at ABC News—it was the first time in his career that he felt

Th e Five Dim e n sion s o f M eta-Le ade rship • The Person: Meta-leaders have emotional intelligence: self-awareness, discipline, balance, and insatiable curiosity. • The Situation: With incomplete information, meta-leaders take a large, complex problem, filter it through a wide range of possible solutions, and clearly articulate it. • Leading Down: They inspire subordinates to excellence. •L eading Up: They “lead” their own bosses, through effective, truth-to-power communication. • Leading Across: They connect to other key leaders across different agencies.

Confident, calm, focused

The benefits of NPLI are quickly apparent in a crisis, says Dorn. “These leaders are confident, calm, focused. They are clear about the overall mission. And people working with a meta-leader know what they have to do to help accomplish the mission.” In March 2009, for example, a novel strain of influenza, dubbed H1N1, surfaced in Mexico and spread to the United States. By late April, the outbreak had hopscotched across the globe. It was what public health offi-

he was drawing on all of his strengths in the face of a public health crisis. During the H1N1 response, “I deliberately tried to make sure I was hitting all of the leadership domains within the NPLI meta-leadership approach,” says Besser. “You have to look at leading yourself, leading the event, leading across silos, leading up, and leading down.” The most compelling proof of the program’s success is the fact that many NPLI alumni occupy positions of influence at federal, state, and local health agencies. “When H1N1

hit,” says Marcus, “most of the senior CDC leaders had been through NPLI.” “In choosing students for NPLI, we don’t pick the appointed leaders— the Secretary or Assistant Secretary,” adds Dorn. “We pick the highest government service employee in that organization, because they’re the ones who are going to persist and eventually lead.” Madeline Drexler is editor of the Review.

Fall 2011

17

Today, among the 87 war-torn countries in which data have been gathered, 300,000–500,000 children are involved with fighting forces as child soldiers. Some, as young as seven, commit unspeakable atrocities: killing parents and siblings, assaulting neighbors, torching the villages they once called home. Some are forced to serve as sex slaves. Many are injected with drugs to curb their inhibitions against committing violence. Once the killing ends, peace treaties are signed and emergency humanitarian missions pull out. But these children’s sorrows persist. Theresa Betancourt has made it her mission to understand how to promote their resilience—and ultimately, their healing.

18

Harvard Public Health Review

Helping Former Child Soldiers Become Whole Again

Sven Torfinn/Panos ŠStuart Freedman/PANOS

A 14-year-old former child soldier in Sierra Leone

Fall 2011

19

From child soldier to productive citizen

In Sierra Leone, assistance quickly evaporated after

Betancourt, ScD ’03, directs the Research Program on

the African country’s crisis was no longer in the news.

Children and Global Adversity at the François-Xavier

Today, Sierra Leone ranks 11th from the bottom on the

Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights at

UN Human Development Index of 169 nations. Its dis-

Harvard School of Public Health. For nine years, she

trict health officers are justifiably preoccupied with high

has tracked the emotional fate of former child soldiers

rates of maternal and infant mortality. The country has

and explored how—and if—this war-scarred cohort

one psychiatrist—who practices in the capital, Freetown,

can go on to lead meaningful and productive lives.

and is soon to retire.

Using both surveys and one-on-one interviews,

Betancourt’s research seeks to show how former child

Betancourt has painted a psychic portrait of young

soldiers and other war-affected youth may be helped, de-

people—coolly referred to in the academic literature

spite such limited resources, to become contributing mem-

as “children formerly associated with armed forces and

bers of society as adults. She has disseminated her findings

armed groups”—who struggle to find a place in tat-

to hundreds of professionals from local and international

tered postwar societies. She is now adapting and testing

NGOs and UN agencies working with Sierra Leone’s for-

group interventions for troubled youth in Sierra Leone

mer child soldiers.

that have proven successful in other places riven by violence.

She hopes that one day these accomplishments can be bolstered by a broader continuum of care—one that

“ People were pointing fingers at us, saying that this one killed my father, this one killed my mother, that other one burnt down our house.” —male former child soldier Dust cloud—or lasting care

extends from everyday citizens who give troubled kids

“We need to devise lasting systems of care, instead of

encouragement and guidance to frontline community

leaving behind a dust cloud that disappears when the

health workers to psychologists and psychiatrists, who

humanitarian actors leave,” says Betancourt, who is also

can manage cases needing a higher level of services. In an

an assistant professor in the Department of Global Health

ideal world, grassroots mental health services would offer

and Population.

a place for sufferers to tell their stories, talk about their dreams and ambitions, and develop trusting relationships.

HSPH Fellowships En route to earning her doctorate in 2003 at HSPH, Theresa Betancourt received crucial financial aid. In 1998 and 1999, she was awarded a Taplin Fellowship, which paid her expenses. In 1998, she held a Saltonstall Fellowship at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, which helped launch her field research on the Chechnya conflict. In 2008 and 2009, she received the Julie Henry Junior Faculty Development Award, which supported Betancourt’s Family Strengthening Intervention project in Rwanda, a pilot study to bolster resilience and prevent mental health problems among children in postgenocide Rwanda whose families are affected by HIV/AIDS; the research led to a National Institute of Mental Health grant.

20

Harvard Public Health Review

“ We need to devise lasting systems of care, instead of leaving behind a dust cloud that disappears when the humanitarian actors leave.” — Theresa Betancourt, assistant professor of child health and human rights, Department of Global Health and Population

“The postconflict environment is where things break

In Bethel, where the majority of residents were

down, but also where we can help,” she says. “We don’t

Yup’ik, Betancourt acquired both an insider and outsider

have time to waste.”

perspective. “My friends were Yup’ik. I had Yup’ik baby sitters. I spoke Yup’ik. We were outside the dominant

From Alaska to Africa

culture—but we needed to understand that culture in

Betancourt’s path to Sierra Leone began in the Alaskan

order to live well.”

permafrost. She was born in a Native hospital in Bethel,

Her father’s passion for Ethiopia never waned. When

a town near the state’s west coast that then numbered

friends came over for dinner, he would haul out his slide

about 3,000. Her parents, both Caucasian, imbued the

projector and display pictures from his Peace Corps days.

family with a passion for other cultures. Her father was

“We were in small-town Alaska permafrost,” Betancourt

a math and science teacher who had joined the Peace

says, “but we always knew what Africa looked like.”

Corps in the early 1960s, stationed in Ethiopia. Her

Initially trained as a counselor using expressive

mother worked in remote villages for the federal infant

arts in therapy with children, Betancourt started focus-

learning program.

ing in 1995 on children affected by war. First with the

Kent Dayton/HSPH

continued

Studying is a source of encouragement. I know that if I am educated, I will be successful and people will appreciate me.” —female former child soldier

Fall 2011

21

Tragedy Told by the Numbers Child recruits in the Sierra Leone civil war interviewed by Theresa Betancourt’s research team had been severely traumatized by their experiences:

70% had witnessed beatings or torture.

63% had witnessed violent death.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, then with the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a New York-based humanitarian organization, she worked with young refugees in Albania, Chechnya, and the Eritrea-Ethiopia border, organizing emergency education programs and eventually research initiatives. In 2002, at the end of a bloody 11-year civil war, Betancourt made her initial trip to Sierra Leone to work with the boys and girls there. “The first time I met with former child soldiers, what struck me was that they looked really little, really young. They told me they were 13 and 14, but they looked eight. They were malnourished and wearing tattered clothes. I couldn’t fathom what they had seen.” Betancourt has now been tracking more than 500 former child soldiers, many of whom are growing into adulthood and starting their own families. Her main questions: What helps young people endure this experience and still thrive? What qualities of the individual, the family, and the

77%

environment shape resilience? How can effective interventions, resonant

saw stabbings, chopping, and shooting close-up.

with the local culture, be delivered by community members who receive

62%

“ The first time I met with former child soldiers, what

had been beaten by armed forces.

struck me was that they looked really little, really

52%

special training and routine supervision?

young. They told me they were 13 and 14, but they looked eight...I couldn’t fathom what they had seen.”

witnessed large-scale massacres.

—Theresa Betancourt

39% had been regularly forced to take drugs such as marijuana and cocaine.

45% of girls and 5 percent of boys had been raped by their captors.

had killed or injured others during the war. A child soldier in the Democratic Republic of Congo

22

Harvard Public Health Review

©Sven Torfinn/Panos

27%

Drawings by a former child soldier in northern Uganda describe his experience as an abductee.

Groundbreaking research tells the story

and recurring violent images. Not surprisingly, those who

Betancourt believes both numbers and words are needed

committed extreme acts of violence, or were its victims,

to take the measure of a child soldier’s trauma. As a

tend to suffer the most persistent mental health problems

result, she relies on both quantitative and qualitative

and need the most intensive care.

methods in her research efforts. In her longitudinal

Frequently, these children have difficulty with com-

study, she uses a detailed questionnaire to elicit the boys’

munity relationships after their release. They struggle with

and girls’ war and postconflict experiences. Her local

guilt and shame. They are labeled as different or untrust-

staff conduct in-depth qualitative interviews of the chil-

worthy, which, in a vicious circle, deepens their sense of

dren and their caregivers, along with focus groups in the

isolation. In their home communities, they are blamed for

community.

having destroyed lives, homes, property, and society itself.

Much of the existing scholarship on intergenerational relationships in war-exposed populations is based on the experiences of Holocaust survivors. Betancourt’s

Those who are socially isolated are especially vulnerable to addictions and abusive relationships. Girls face a compound burden. They are more likely

work is, therefore, groundbreaking. Her nine-year proj-

to suffer depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress

ect following male and female child soldiers in Sierra

disorder, compared with boys. Some have returned to

Leone is Africa’s first such prospective study.

their communities having had unwanted pregnancies dur-

And a 2007 study that Betancourt co-authored was

ing their times with rebel groups. At home, they face the

one of the first randomized controlled trials of mental

double stigma of having participated in violence and being

health interventions among African adolescents affected by

seen as “impure,” regardless of their war experiences.

war—and one of only a handful of trials of psychological treatments for depression conducted in a developing coun-

Hundreds taught to work with former child soldiers

try. Among other things, she has shown that effective treat-

To grapple with these problems, Betancourt and her

ments—and clinical trials of these treatments—are feasible

colleagues have looked to existing evidence-based mental

in poor, rural, illiterate, war-torn communities.

health interventions that help violence-affected youth manage their emotions and build interpersonal skills. The

A vicious circle

goal is to forge connections to families and communi-

In Sierra Leone and elsewhere, former child soldiers

ties, and give children the wherewithal to negotiate the continued

suffer nightmares, intense sadness, intrusive thoughts,

Fall 2011

23

A Recipe for Resilience Former child soldiers are not a monolithic population of the emotionally wrecked. “When people think of child soldiers, they think of people who are terribly damaged in some way,” Theresa Betancourt says. “But I’ve seen very much the opposite: tremendous stories of resilience, of acceptance, of love in families.” In her view, resilience springs from a complex ecology of individual traits and social forces. “In one sense, any child who made it through the war alive likely developed survival strategies to navigate a harsh and dangerous environment. Some of these young people, especially those who survived abuse, possess a sense of resourcefulness, which shows up in confidence and a sense that they can control their fate.” Another potent factor in resilience is family connectedness. When parents openly embrace their sons and daughters and bring them back into the fold, it not only sustains the child but also sends a signal to the larger community that the boy or girl is worthy of acceptance and care. Going to school, doing homework, and graduating likewise foster a sense of normalcy and regaining lost time. How the wider culture draws meaning from the war and its aftermath also influences the fate of former child soldiers. During the postwar, government-led process, which has included sanctioned forgiveness and community sensitization campaigns, many young people received the explicit message that their involvement in the country’s atrocities was not their fault.

adversities they often encounter. Ideally, such approaches

Married to a physician specializing in health inequities,

are linked to educational and job programs that restore

and the mother of two young children, she has a notice-

civilian roles—since returning to school or securing a live-

able lightness of spirit.

lihood are prime sources of confidence and motivation in the children. Betancourt emphasizes that direct, sustained treat-

distress has a local meaning

Betancourt is planning pilot studies that use compo-

ment of war-affected children is the task of local part-

nents of cognitive behavioral therapy and an approach

ners. “I like to stay put in a place, develop relationships,

known as group interpersonal psychotherapy that has

and keep working at things over time,” she says. Despite

proved successful in relieving depression among chil-

the oppressive content of her work, she is neither dour

dren—some former soldiers, some not—crowded in

nor drawn to philosophical discussions about the nature

refugee camps in embattled northern Uganda. Group

of good and evil. As she puts it, “I’m very pragmatic.”

interpersonal therapy is based on the idea that the roots of depression, and the mechanisms for healing it, lie in

“ I think about what I have been through and this gives me more determination to do well in life.”

— male former child soldier, recently promoted to his final year of secondary school

people’s relationships with others. Young people who have all experienced the same ordeal can share support, wisdom, and understanding. In Betancourt’s intervention, war-affected young people learn that they are not alone in their experiences and emotions. “The key is being able to put a word to their feelings: sadness, worthlessness, hopelessness, loss of en-

24

Harvard Public Health Review

ergy, the sense that life is not worth living,” she says.

dangers of excluding any stigmatized group. Traditional

“We spend a lot of time trying to learn local terms for

healing ceremonies—such as ritual washings and col-

emotional suffering. Once intervention and problem

lective feasts—can also mark new beginnings for for-

solving begins, these young people no longer feel alone.

mer child soldiers.

Their symptoms start to lift.” Betancourt and her team call their pilot model the

Such evidence-based interventions are far more effective than the once-popular technique in humani-

Youth Readiness Intervention, because it builds readi-

tarian assistance known as “psychological debriefing,”

ness to succeed in critical aspects of life such as personal

in which Western practitioners briefly visit war zones,

relationships, taking care of one’s self, planning for the

conduct therapies in which victims talk about their

future, and achieving economic self-sufficiency. Meeting

traumatic experiences, then leave.

weekly for two months, the participants focus on the

According to Betancourt, “Flying in and asking

present: setting goals, curbing high-risk behaviors and

someone to share their trauma in one or two sessions,

substance use, reducing trauma-related distress, and

without an ongoing, safe therapeutic relationship, can

boosting community involvement.

actually do more harm than good.”

Complementing African programs and traditions

Not a “lost generation”

“The groups fit well in collectivist cultures such as in

In the aftermath of chaotic civil wars, investments in

Uganda or Sierra Leone,” says Betancourt. “In northern

psychosocial and mental health problems are typically

Uganda, we saw very strong effects in girls, more so

phased out as the problem shifts to a postconflict and

than in boys. That may be because in these crowded

then a reconstruction phase. “Unfortunately, these chil-

camps—where girls had a lot of responsibilities caring

dren’s needs do not follow a similar phasing-out process,

for people, cooking, gathering firewood, fetching

particularly when they have been ill-addressed at the

water—they didn’t have much in the way of supportive

outset,” says Betancourt. “There is real difficulty in

social contacts before meeting other girls in the same

getting funding for this work. Sierra Leone, in partic-

situation.”

ular, is seen as a ‘has been’ conflict: no longer sexy.”

Betancourt’s locally adapted models also comple-

What most worries her is that societies will write

ment what has been initiated in Sierra Leone and other

off former child soldiers as a “lost generation.” The op-

nations, including “sensitization” campaigns that en-

posite could be true, she contends: The very qualities

courage communities to discuss the conflict and the

that helped these children survive a harrowing experience may also enable them to catalyze change in their shattered homelands. And while Betancourt’s research may seem specialized, many of her findings transcend culture. “When someone’s a survivor, it means they are still here today, despite what they went through,” she says. “It would be

©Giacomo Pirozzi/PANOS

terrible if people who had been through events like this saw themselves as hopeless or as victims. A survivor orientation means being able to feel the strength of what it takes to make it through such horrendous experiences and still move forward in life.” Former child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo have received skills training as part of their reintegration into society.

Madeline Drexler is editor of the Review.

Fall 2011

25

Infectious Diseases

Unlocking the Secrets of Drug Resistance in Malaria Parasites New gene search tool opens “endless possibilities”

D

uring a half-century of global efforts to conquer malaria, scientists have developed a series of anti-

“If resistance to artemisinins develops and spreads to other large geographical areas, as has happened before with

malarial drugs, only to see them defanged, one by one, by

chloroquine and sulfacoxine-pyrimethamine (SP),” the

the shape-shifting parasite’s ability to rapidly evolve drug-

World Health Organization warned in 2009, “the public

resistant variants.

health consequences could be dire, as no alternative antima-

Today, with massive new malaria eradication cam-

larial medicines will be available in the near future.”

paigns launched against the disease that kills nearly a million people every year in Africa, drug resistance remains

Early warnings KEY

a critical problem—and one whose molecular underpin-

Today, these rogue strains are usually recognized only

nings are poorly understood.

when patients stop responding to a drug, says Dyann

The antimalarial medicine chest has dwindled to a

Wirth, chair of the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at Harvard School of Public Health

became available in 2005. And now doctors in Southeast

and a co-director of the Infectious Disease Initiative, a

Asia are seeing signs that artemisinin may be next on the

collaboration that involves Harvard University and the

parasite’s hit list.

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. “By the time you find a very resistant parasite,” she says, “you’ve already lost the battle.”

26

Harvard Public Health Review

Comstock/Getty Images

single reliably effective compound, artemisinin, which

With this threat always at hand, new research at HSPH is addressing an urgent need: early warning methods to detect the first signs of drug-resistant malaria strains, so that a swift response might keep them from gaining a foothold. Watching resistance unfold

In April, Wirth and other leaders of the Initiative reported on a powerful combination of genome search methods that enabled them to discover new resistance genes in Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria parasite. They even used one of these genes to convert a docile, easily killed parasite into a resistant one. “We really didn’t know what to expect,” says Daria Van Tyne, a graduate student in Wirth’s lab and co-first author of the study, which appeared in PLoS Genetics. “This is the first time anyone has observed resistance as it’s happening.” At the molecular level, little is known about the pathways leading to resistant phenotypes. At HSPH, Wirth and her colleagues are looking for clues by comparing the genomes of resistant parasites with “sensitive” or nonresistant organisms. “Our approach is to develop a tool that will enable us to observe a tendency toward loss of drug sensitivity in a population before the problem is well established,” explains Wirth. “The goal is to make the discovery early so you can use that knowledge to focus efforts,” such as enforcing appropriate drug-use guidelines. Five first authors

The PLoS Genetics paper is unusual in having five co-first authors (including Van Tyne) and three senior authors: Wirth, HSPH research scientist Sarah Volkman, and Pardis Sabeti of the Broad Institute and Harvard. “This is a very strong collaboration,” Wirth notes. The research drew on HSPH expertise in parasite biology and drug resistance mechanisms, the Broad Institute’s resources in sequencing, genotyping, and computational methods, and field researchers in Senegal who track the spread of resistance. Contributions also came from investigators at other U.S. universities and at universities in Senegal and Nigeria.

Searching for resistance genes

The National Institutes of Health maintains a depository of malaria parasites from around the world collected over decades. Tapping this resource and the labs of HSPH partners in Africa, the researchers collected 57 parasites from three continents—some of them sensitive to antimalarial drugs, and others resistant to one or more. Though the first P. falciparum genome was sequenced in 2002, only recently have malaria scientists begun genomic searches for resistance genes.

Dyann Wirth, chair of the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases (left) and Pardis Sabeti, assistant professor in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases

For their study, the HSPH and Broad investigators began by scanning the parasites’ DNA for regions that had undergone recent evolutionary changes, some of which might reflect adaptation under selective pressure from malaria drugs. With this method, the scientists identified 15 genes showing signs of recent selection. Determining which of these genes were implicated in resistance required a second step—a genome-wide association study, or GWAS. The GWAS search drew on HSPH researchers’ expertise in molecular biology and drug resistance, combined with the Broad’s prowess in gene sequencing and computational biology. continued

Fall 2011

27

The GWAS was designed to home in on genetic variants present in parasites resistant to 13 antimalarial drugs, but not present in drug-sensitive ones. The scientists constructed a fine-resolution map of more than 17,000 points of reference, called SNPs, spaced regularly throughout the genomes; it was the densest SNP array yet applied to the malaria parasite.

The GWAS netted several new resistance-associated genes, including one, dubbed PF10-355, that looked like a particularly strong candidate. To test this further, Van Tyne transferred PF10-355 into a drug-sensitive parasite. Sure enough, the addition of the gene increased the parasite’s resistance to three related antimalarial drugs. Daria Van Tyne, HSPH graduate student

“ By the time you find a very resistant parasite, you’ve already lost the battle.”

28

Harvard Public Health Review

Kent Dayton/HSPH

artemisinin is losing its effectiveness in a certain population or geographic area. According to Wirth, “That — D yann Wirth, chair, HSPH Department of would tell us that we need to use Immunology and Infectious Diseases other drug combinations and implement focused intervention strategies “We had no idea if it was going to prevent the spread of resistant Genes to the globe Wirth and others involved in the to work or not,” Van Tyne said of parasites.” project say the new genomic search the two-pronged method. Much to And, Van Tyne says, “this the scientists’ relief, the searches im- tool opens up “endless possibilities” would all feed into research that that could lead to improvements in mediately detected a gene for chlocould yield better antimalarial detecting and combating antimaroquine resistance that had been drugs.” larial resistance. discovered previously with older It would be hard to find a better “The paper we published is techniques. This validation that story illustrating Dean Julio Frenk’s just the tip of the iceberg,” explains they were on the right track “made “genes to the globe” concept, adds Van Tyne. With these new genomic us very happy when we saw it,” reWirth. “Harvard has the ability to tools, researchers can search not calls Van Tyne. “It gave us a green approach a problem like malaria only for resistance genes, but also light for the rest of the study.” from a fundamental understanding other mutated or variable genes that of the biology all the way to global govern parasitic traits and the difissues like policy, finance, and all ferent outcomes that infected people the pieces needed to address public experience. health problems.” Their greatest hope is that disRichard Saltus is a Boston-based tinctive resistance-related mutations freelance science journalist. could become the basis of simple blood tests, able to be performed in Sarah Volkman, HSPH community clinics in Africa, that research scientist could determine when a drug like

Fellowships

W

hen Roy Wade was a medical resident at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, one patient in the pediatric clinic he was working in really stuck with him: a 16-year-old girl with a deeply troubled history of depression and risky behavior. “I couldn’t help, and her life spilled out of control after my visit with her,” he recalls.

Dora Hughes, MPH ’00, counselor to U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius

The case highlighted for Wade the difficulty of helping patients with problems that are not just medical, but tied into the fabric of lives marred by poverty, racism, a family history of illegal drug use, chronic disease, or physical and emotional abuse. When Wade heard about the Commonwealth Fund/Harvard

Yvette Roubideaux, MPH ’97, director of the Indian Health Service

University Fellowship in Minority Health Policy, “It just clicked for me,” he says. Looking to boost his skills as a leader within the health care system, he applied for and received a Commonwealth Fellowship to study at Harvard School of Public Health, completing the program to receive a master’s in continued public health in May.

Kima Taylor, MPH ’02, director of the Open Society Foundation’s National Drug Addiction Treatment Program

Roy Wade, MPH ‘11, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

A Launchpad for Leaders Fellowship program nurtures physicians’ “inner advocate,” propelling them into roles helping national and global stage Fall 2011

29

Kent Dayton/HSPH

the disadvantaged on a

Illustrious alumni

covers not just policy and leader-

ment. Wade identified a need for

In doing so, Wade, MPH ’11, joined

ship issues, but nitty-gritty subjects

improved communications between

an illustrious group of alumni that

such as accounting, epidemiology,

health centers, the states, and private

includes the current head of the U.S.

communications, and economics—

payers as key avenues for improving

Indian Health Service, a key health

all of which may be quite new to

the finances of school-based health

policy adviser to President Barack

young physicians.

centers in the future.

Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen

Focusing young leaders

Prophetic connections

Sebelius, and at least one MacArthur

Critically, the program helps each

Yvette Roubideaux, MD, MPH ’97,

Foundation “genius grant” recipient.

fellow identify the issues that engage

who now heads the U.S. Indian

him or her most. “We all want to

Health Service (IHS), participated in

celebrated its 15th anniversary

address social inequities, social injus-

the program in its earliest years.

earlier this year, provides potential

tice, poverty, and racism—issues that

physician-leaders with the skills they

affect public health,” Wade points

Rosebud Sioux nation, attended

need to help people who come from

outs. “We come to the program with

a talk during her fellowship that

Obama and U.S. Health and Human

The prestigious program, which

Roubideaux, a member of the

“ Without this fellowship, I doubt that I would have been able to make the same kind of impact on African women’s health and female genital cutting.” —Nawal Nour, MPH ‘99 minority, disadvantaged, or otherwise

ideas about what we want to work

was given by the IHS’s then-

vulnerable groups get better access to

on, and the program is very good

director. HMS Dean for Diversity

high-quality health care.

at helping us refine those ideas into

and Community Partnerships

our respective research and policy

Joan Reede (who heads the

School (HMS) in 1996, the program

areas, and at providing avenues for

Commonwealth Fellowship

offers recipients funding to pursue a

us to continue to work in these areas.

program) told Roubideaux that she

master’s of public health from HSPH

Doing projects on the child welfare

should pay strict attention, making

or a master’s in public administration

system, I realized that’s where I want

the prophetic suggestion that

from the Harvard Kennedy School of

to work.”

Roubideaux herself might eventually

Launched by Harvard Medical

Government. Since its establishment, the

Each fellow carries out a practicum analyzing a highly specific issue

get the speaker’s job. “The fellowship broadened my

Commonwealth Fellowship,

in health policy. For Wade, that was

perspective and gave me new tools to

combined with funding from the

an analysis of school-based health

keep focused on my original goals,”

California Endowment Scholars in

care centers, which provide a major

says Roubideaux, who later switched

Healthy Policy and the Joseph Henry

safety net for 2 million patients but

career plans toward teaching,

Oral Health Fellowship in Minority

often face severe funding handicaps.

research, and service. (To learn more

Health Policy, has supported 99

While most of these centers bill their

about Roubideaux’s career, read the

fellows in minority health policy,

states for Medicaid reimbursement,

profile that appeared in the Spring/

95 of them at HSPH. The training

managed care organizations often

Summer 2010 Review at http://www.

raise barriers for this reimburse30

Harvard Public Health Review

“ It’s nice to know you have a support system, but we all know that it comes with an expectation—that we will be part of an extended group that helps to nurture the fellows who follow,“ —Kimberly Cauley Narain, MPH ‘11 hsph.harvard.edu/news/hphr/spring-

that seeks to boost access to treatment

2010/spr10roubideaux.html.)

for addicts by rethinking advocacy,

Fellowship was a career-altering

communications, and operational

experience,” says Nour, who is asso-

Tackling drug addiction

strategies. While results vary by state,

ciate professor in obstetrics, gyne-

treatment

so far the program has opened up

cology, and reproductive medicine

Kima Taylor, MPH ’02, now directs

access to treatment for 300,000 more

at HMS and director of the obstetric

the Open Society Foundation’s

people, she says.

ambulatory practice at Brigham and

National Drug Addiction Treatment

“The Commonwealth

Women’s Hospital.

Program, which directly tackles the

Advising Obama

challenges posed by lack of access

For Dora Hughes, who received

after the fellowship as a public

to treatment for the more than 23

her MPH from HSPH through the

health practitioner with the goals

million people addicted to drugs

program in 2000, the fellowship “let

of bringing about social change to

and alcohol in the U.S.

me be effective on a much broader

improve women’s health,” says Nour.

“Only 10 percent are being

field.” After working as an aide to

“Without this fellowship, I doubt

treated,” says Taylor. “It’s a chronic

Senator Ted Kennedy and to then-

that I would have been able to make

disease and it needs to be treated

Senator Barack Obama, she became

the same kind of impact on African

that way—handled in the health

a health care adviser during Obama’s

women’s health and female genital

care system and not the criminal

presidential run and now plays a

cutting.”

justice system. It’s also still publicly

major role in health care initiatives as

stigmatized and seen as a moral

counselor to HHS Secretary Sebelius

Paying it forward

failing, even by many MDs and

in the Obama administration.

“One of the most powerful aspects of

“I returned to clinical work

the fellowship is the camaraderie and

others in health care.” Eradicating genital cutting

the family atmosphere,” Roy Wade

opened my eyes to professional

Other fellows who attended HSPH

points out. “You feel absolutely

possibilities that I would not have

through the program include Nawal

supported. You are able to express

known even existed. It exposed me