32 minute read

Southern Stumpin

SOUTHERN STUMPIN’ Cooperation

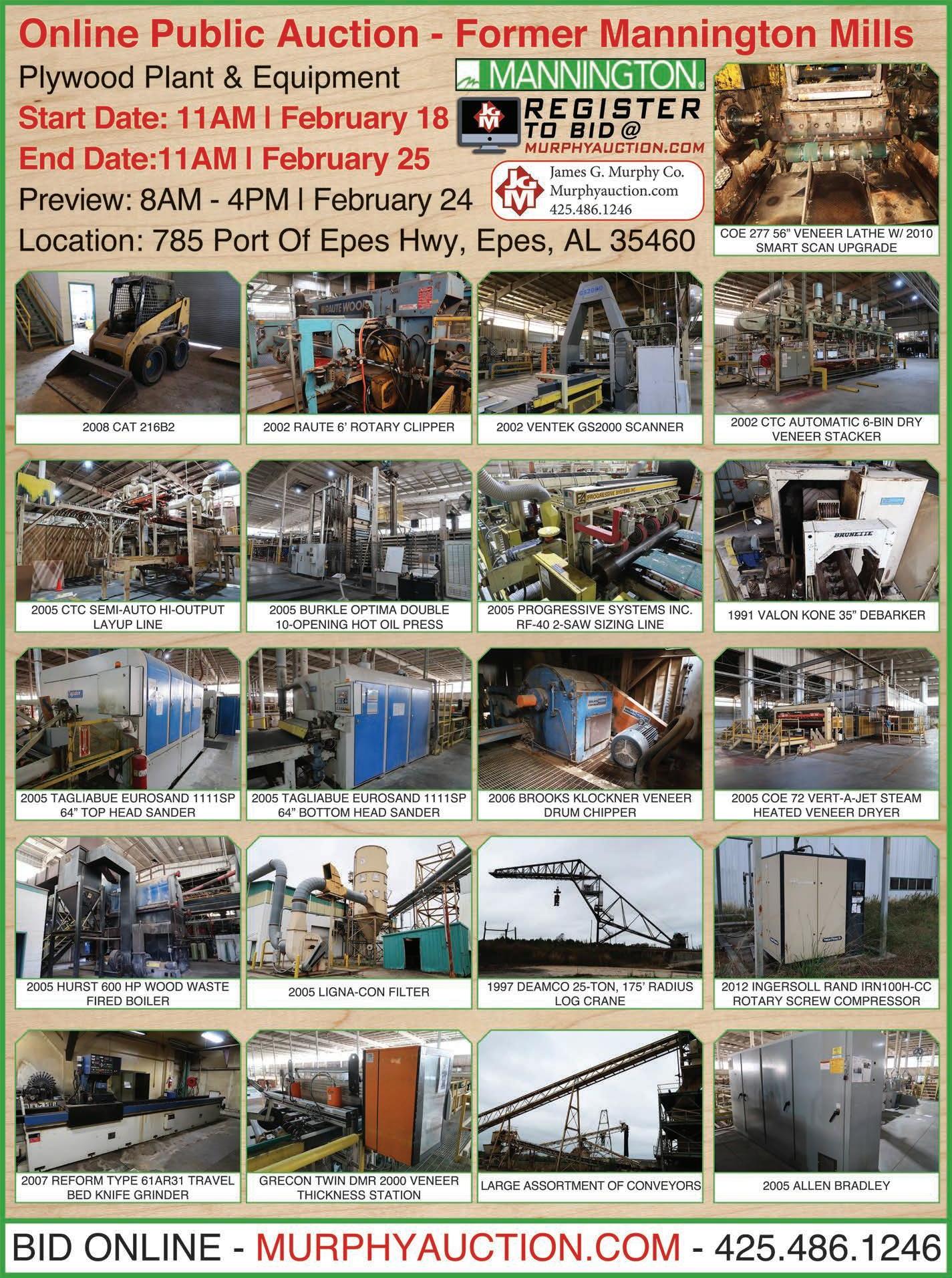

EDITOR’S NOTE: My friend at the Virginia Log gers Assn., Ron Jenkins, asked if we could publish this article by Michelle Stoll, Director of Public Information, Virginia Dept. of Forestry. I was happy to make a space to accommodate his request. It previously appeared in the December 2020 edition of the VLA's newsletter.

Remember those old cartoons with the coyote and the sheep dog clocking in to work, the coyote set on eating the sheep and the sheep dog determined to stop the coyote? These two were always at odds and that was just the nature of their jobs. Well, some people may assume the same is true for Virginia Department of Forestry (VDOF) water quality personnel and loggers, but they would be wrong! “We’re really on the same side and when we work together and keep each other informed, everyone wins,” explains VDOF Water Quality Specialist Kevin Dawson.

Kevin, forestry consultant Todd Goode and logging company owner Donnie Reaves have been working together on a job that proves partnership and communication are more than just words. As a result of pre-planning, intentional and open communication, and a sound relationship built on mu tual interests, one harvest in Lynchburg City has proven to be stress-free and a success for all in volved.

Todd and Donnie contacted Kevin in June of 2020 about a potentially complicated timber harvest in Lynchburg. The site crossed a stream and was in a particularly visible location. The location had all the elements of a difficult job fraught with water quality problems and public scrutiny. Donnie and Todd recognized this and reached out to Kevin to request a pre-harvest plan and assistance with in stalling a temporary bridge.

“Donnie and Todd foresaw the potential issues and reached out for help from VDOF,” Kevin says. “This kind of communication and trust goes a long way to make a positive harvest that everyone walks away happy with.”

The site posed two significant challenges: the need to cross Dreaming Creek as well as a city sewer line running adjacent to the creek. Kevin wrote the pre-harvest plan on June 18, 2020 and submitted it to Todd, Donnie, and Lynchburg City. The plan involved a double bridge crossing at Dream ing Creek, one set of bridges to traverse the sewer line and the second set to cross the stream. Lynchburg City was more than willing to mark the sewer line.

Donnie was able to take advantage of VDOF’s Logger BMP Cost Share Program that takes advantage of funding provided by the Commonwealth’s Water Quality Improvement Fund. This program helps logging contractors cover the cost of implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs) on stream crossing sites across the state. The program covers 50% of the cost of BMP installation up to $2,500, or $5,000 if the project includes the purchase of a portable bridge. Kevin submitted the cost share paperwork at the same time to secure funding to help Donnie with this project.

Donnie knew he needed a bridge that would adequately support his tracked sawhead, and he contacted Binky Tapscott of Forest Pro, Inc., to perform the construction. They settled on a 35-ft. steel bridge with extra I-beams under the outer panels for added strength. The plan also called for logs under the ends of each bridge to make the crossing level and the transition from bridgeone to bridge-two seamless.

“I was very impressed with Donnie’s ability to listen and suggest alternative ways to stabilize the crossing during use,” recalls Kevin. “Donnie used the existing brush on both sides of the crossing to create a corduroy pad that would keep the equipment from rutting the approaches and prevent any potential erosion or sedimentation. He also suggested using two main bladed trails, which was an idea that I had not previously considered, but after listening to his reasoning I thought it was worth a respectable try.”

The job began in August of 2020 and as of Thanksgiving was approximately 75% com plete. The Lynchburg area received separate rain events of four in., five in., and 10+ in. during this harvest and the bridges as well as the approaches have held up better than ever expected. Donnie used a combination of temporary diversions and brush matting to prevent soil compaction, soil rutting, erosion, and sedimentation. Kevin explains that each week he has responded to many phone calls questioning the project and has conducted weekly inspections of the property because he knows that there are many eyes that view this harvest daily. He has yet to find any erosion or sediment entering the stream channel. Once the project is completed the bridge will be removed, VDOF will close out paperwork for the Logger BMP costshare project and process the payment.

“I’ve seen pictures of the bridge with a bulldozer sitting on it after heavy rains, the creek swollen, an incredible amount of fast-moving water, all while the stream banks look undisturbed by the logging,” according to VLA Executive Director Ron Jenkins.

Donnie’s willingness to listen and take the time to install the necessary control measures during the harvest made this endeavor successful. In addition to Donnie’s efforts to enlist VDOF’s expertise and involvement prior to beginning the harvest, the City of Lynchburg has also been an important stake holder. “They have been great to work with, and I keep them informed on a regular basis with any developments I observe while conducting my harvest inspections,” Kevin says.

This job is a perfect example of what happens when the communication between parties is open and honest. All parties have been willing to listen to one another, and that makes things simple when it comes to complicated harvests. “I think the en tire proc ess has proven that when pre-harvest planning is in volved along with patience and determination that complicated pro jects are not as complicated as they may seem,” Kevin concludes. SLT

(L-R)Virginia state forester Rob Farrell, bridge builder Binky Tapscott (behind), logger Donnie Reaves (front), water quality specialist Kevin Dawson, Virginia Secretary of Agriculture & Forestry Bettina Ring Following several inches of rain, bridge remains strong and the stream remains clear and free of sediment.

By Donnie Reaves

This was a wonderful project created by some great people coming together. It was the WE factor that made it happen and not just one person. Kevin Dawson of the Virginia Dept. of Forestry got it all started off on the right foot by helping me understand our options. Me done did doesses went and found me a goodess water quality man.

When it came to crossing this creek, I counted heavily on Uncle Binky Tapscott to build one that would allow my heavy equipment to cross and keep the water clean. Both men were so important to helping me. Also, I am thankful to Rob Farrell for making the funding available to build the bridge. I sure hope Mr. Farrell didn’t have to give up a paycheck!

Finally, I give the Lord above all the credit for helping to move everyone in the right direction for a successful outcome. Amen!

Carrying On

■ After suffering family tragedies, Chris Cates keeps up his father’s legacy.

By David Abbott

BREMEN, Ala.

When Wayne Cates died of cancer at age 64 in 2016, he must have taken some measure of comfort in knowing the company he started almost 30 years earlier, W. Cates Logging, would be in good hands. His older son Chris Cates, 43, had long since proven himself up to the task.

Chris had already been running the daily operations in the woods for several years by that point, but he still had his dad with him, and Wayne was still ultimately in charge. Now, the son shoulders the responsibility for safeguarding the family name, and the businesses associated with it—the logging and trucking concerns as well as a dirt race track, ECM Speedway. The burden isn’t his to carry alone, though; he has support from his

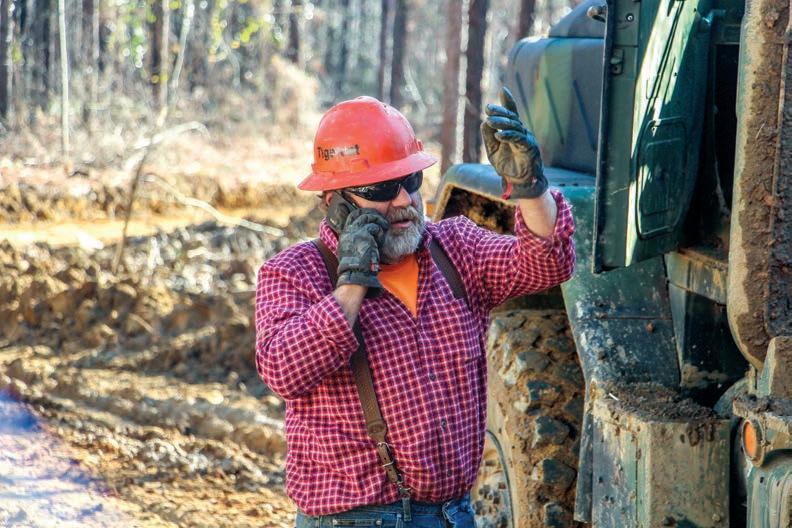

Chris Cates and his mother, Tobbie Stover

Cates added two 610E Tigercat skidders in two years from B&G Equipment in Northport, Ala.

mother and partner, Tobbie Stover.

“Before he got sick, he was healthy as a horse,” Chris recalls of his father. “He worked hard all of his life, every day. He was a nononsense kind of guy.”

Wayne wasn’t a born native to the logging woods. He started his career working in coal mines, but what he really wanted was to drive his own truck. “The coal mine was really doing bad with layoffs, the mine shut down, so Wayne started driving,” Tobbie recollects of her late husband. He bought his first truck from Charles Bishop in 1975. Tobbie and Wayne married in August of ’76 and incorporated their company in ’77, the year Chris was born.

He hauled coal till the coal industry played out, then tried gravel, soy beans, anything to keep the men working—they had five trucks by then going to Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee. “It was just not enough money to keep it going, so we changed from dump beds to flat beds,” Tobbie says. They started hauling lumber north and steel back, Chris says, taking advantage of backhauling opportunities to minimize deadhead miles. Wayne had a bad back made worse by often twice-weekly round trips to Chicago, Ill., or Gary, Ind.

Truck driving kept Wayne away from home more often than not, and soon enough, he and his wife di vorced. “Wayne was a workaholic,” Tobbie says. They remained on reasonably good terms, though, both regarding the business and their sons—Chris had gained a brother, Eric, in 1982.

Chris corroborates his mother’s assessment—“work” was Wayne’s middle name. A few years ago, after he was grown and supervising operations in the woods, Chris wanted to take the crew down to Gulf Shores on a Friday to go snapper fishing, and asked his dad about the idea. Wayne’s reply? “Naah, we ain’t doing all that; we’d have to take off work!” Over time, his enthusiasm for the fishing trip only grew strong er, so Chris again brought it up, and Wayne again shot it down, quick. “Boy, it just galled me that he wouldn’t even consider it,” Chris ad mits, able to grin about it now. “I remember it plain as day. He was sitting there in his chair, and I asked him, ‘Dad, do you not like doing nothing?!’ He looked at me, raised his eyebrows and said, ‘I like to WORK!’ I knew then there was no sense in even asking about it anymore.” ➤ 10

Chris has put 14,000 hours on the 2010 Cat, his first new loader; his dad, company founder Wayne Cates, bought it for him.

From left, Donnie Collins and “TNT” Jonathan Hosner Left to right, Carles Farr, Chris Cates, Matthew Anderson and Randy Williams

9 ➤ After the divorce, years clearing that land with trac- work with his parents, in the shop Wayne ached to be home to tors and dozers. “They cleared after school and on weekends, and see his sons more, though he about 300 acres, the old fashioned he worked in the woods with his dad had no intention of giving up way,” Chris says. every summer. In his junior and senhis trucks. He called Tobbie Wayne had enjoyed that part of ior years, as soon as he turned 16 and informed her he planned it, so when he made the choice to and could drive, Chris co-opted, to start a logging business so quit hauling over the road and be leaving school after half a day to go he could be home at night for home more, logging was an easy to work on the logging crew. the boys, and she agreed it fit. He started W. Cates Logging After graduating, he says, “My was a good idea. with Mike, his baby brother. dad had big hopes for me; he was

Wayne wasn’t entirely Tobbie remembers that her going to send me to Auburn, to for without a background in tim- older son had always shown an estry school, and I would buy our ber. His father had bought interest in helping with the family timber.” The plan didn’t pan out. “I river land in the ’60s, during business. Chris started helping at was 18, it was the first time I had construction of the Smith the shop when they were still ever been away from home and I Lake dam project. He want- hauling coal; she says even before didn’t have my priorities in line,” ed to farm it, but most of it he could walk, he was talking on Chris admits. He made it about six was covered in timber. He the CB radio she used for truck months before Wayne told him, and his sons, Cecil, Don, dispatch. He recalls that even as a “You ain’t cut out for that, boy, you Wayne and Mike, spent kid he always wanted to be at need to come on back to the woods.” And that’s where Chris has been ever since. “It’s all I’ve ever done.” Chris worked with his dad and uncle for years, gradually earning the foreman role. Eric also sometimes drove a truck for the business. They’re all gone now, though; Eric was killed in 2015, and Wayne and Mike both died in 2016, leaving Chris and Tobbie to carry on the family businesses.

Cates stays on top of things.

Cates loads set out trailers and moves to a staging area with an Army truck.

Operations

Today, woods equipment includes a 2010 Cat 559B loader with 14,000 hours on it, still running well. “It’s a good machine,” Chris says. “Daddy bought that one for me; that was my first brand new knuckleboom.” Chris himself put most of the hours on this machine; he just hired its current operator, Jonathan Hosner, the first of this year so that Chris could start driving set out trucks. When someone set fire one weekend to another old-but-good Cat, a 525C skidder, Chris set out looking for a replacement. “I wanted another Cat, but I had just bought a new 610E in October 2018, and I didn’t really want to stack two payments up,” he says. “So I looked around at

auctions, but everything either had too many hours or was beat up, so I just wound up buying another 610E in May 2020.” Carles Farr, who has been on the Cates crew since 1991, mans the ’18 model, while Donnie Collins, with Cates since 2011, drives the newer 610E. Cates added a Tigercat 234B loader in 2019, run by Matthew Anderson, and a John Deere 843K handles felling. Cates keeps a 573 Cat cutter as a backup; in some cases they run both cutters, but most of the time operator Randy Williams keeps enough cut for both crews with just the Deere. The crews generally work on the same tracts but with separate loading ramps.

Cates Logging does business with dealers B&G Equipment in North port for Tigercat, Warrior Tractor in Athens for John Deere and Birmingham-area Thompson Tractor's satellite branch in Dodge City for Cat machines.

Four full-time truck drivers haul for Cates Logging, but one of them, Ricky Boyd, has been hospitalized with Covid-19. “Ain’t no doubt about it, it’s bad,” Chris acknowledges of the disease. “It’s definitely a bad deal for anyone with any kind of health problems, and Ricky had a mild stroke right before Christmas.” Boyd had been on a ventilator for two weeks when Southern Loggin’ Times visited in mid-January. The other drivers are Tony Watkins, Billy Joe Johnson and Paul Mote.

Chris uses Army trucks to move set out trailers to a clearing near the paved road so truck drivers can drop off empties and pick up full trailers without having to wait under the loader. It saves them about 40 minutes per load, Chris figures.

The crews work within a 50-mile radius from home, mostly in plantation pine, generally thinning to a 70 basal area. Cates cuts primarily for Heath Albright at Brighton For estry of Holly Pond and Joey King at Jasper Lumber in Jasper. With five Kenworth trucks, ’97 to ’11 models, and eight trailers (Pitts, McLendon and OT), the crews average 60 loads a week.

When Wayne started his race track (see sidebar, p. 14) and left Chris in charge of logging, he continued to have a hand in the business. Driving—a truck or a race car—was always what he loved best, so most of the time that’s what he did. Just two years before his death, he bought a new truck that, despite some early problems with it, was his pride and joy. He had his picture made with the first load he pulled with it; Chris and Tobbie had that picture put on his tombstone.

“Some of these guys seem like they make pretty good money buying their own wood, but I tell you, this business, you ain’t gonna get rich doing it the way I’m doing it,” Chris admits. “I love it, I reckon. I’ve thought about it and I can’t think of anything else I’d rather be doing,” he offers after a moment’s pause for consideration. ➤ 14

Left, patriarch Wayne bought his favorite truck in 2014; after Wayne’s death, Billy Joe Johnson, right, now drives it.

In 1990, Chris’ grandfather en rolled his farm land in the CRP— conservation reserve program, part of the Farm Bill that year—for 10 years. “They told him that he could plant it in pine and they would pay for 90% of it,” as Chris recalls. “Well, hell, he’d spent his whole life clearing all that farm land, and he damn sure wasn’t going to plant trees on it again. So they paid him so much a year just to keep it bush hogged. That’s about the time our government started selling us out to China. They went to paying our farmers to let their land sit there and do nothing so we could buy foreign products at a cheaper price and starve our folks out.” When the 10 years was up, Mr. Cates was in his 70s. He was too old to work the farm—there comes a point in a man’s life when his body just can’t handle the physically demanding labor of farming, or logging, even more so then than now. “If I had to do it the way my dad and uncle and papaw had to do it, I wouldn’t be doing it or I wouldn’t love it near as much, I promise you,” Chris is not too proud to admit.

Mr. Cates also didn’t get much in social security because he’d never worked for anyone else very much. Looking at his limited income, he decided he’d sell each of his six children what they wanted of the land, 460 acres, for $1,000 an acre. The money went in a trust and he lived off the interest. When he died, his heirs got their land and their money back. “It worked out good for him and good for us,” Chris says.

Eventually, Wayne ended up with 160 acres. “We didn’t have time for cows with this logging stuff, so we thought about planting it back in timber, and I sometimes wish we had,” Chris admits. But Wayne decided on a different direction. He and Eric had gotten into dirt track racing. “Eric loved to race,” Tobbie says. By then a teenager, Eric had started going the

wrong direction with the wrong crowd, and Wayne hoped this hobby might help keep him out of trouble. They had been racing at the Hanceville Speedway, but when it closed, Wayne decided to build his own speedway.

“He was always up for a project,” Chris says. “I had been in the woods long enough that I knew what to do, and daddy felt confident enough to let me run the dayto-day operations in the logging.”

The project, started in 2000, took a year to complete. The logging crew actually helped. “The market in logging had gotten pretty bad, and we just had all our stuff paid off already,” Chris re calls. “Daddy needed a few hands to move dirt, so we just halted operations on the woods work for about four months and helped finish the race track.” River Valley Speedway, named for its location near the Mulberry River, opened in 2001.

Building it was one thing; managing it was slightly out of Wayne’s wheel house. “Daddy loved racing but he didn’t ever work with the public,” Chris explains. “He always worked for himself and didn’t answer to nobody. He wouldn’t go around and get sponsors. He didn’t tell me this, but I read between the lines: he felt like he was begging. He didn’t want to ask nobody for nothing. So he tried to do it by himself.” That made it a tough row to hoe. Chris con tinues, “Some weeks you can do pretty good, if all the pieces fall to gether and you put

It was renamed after Eric's death.

together a pretty good race. But I learned from watch ing him: you have to promote and you can’t do it without help. You have to spend money making the place better for people to come.”

From April till Labor Day they run the speedway just about every Saturday night, usually with 70 cars. Spectator tickets are $10 a head in the general side and $35 in the pits. It usually starts about sundown and ends around midnight.

On October 31, 2020, the track— renamed to Eric Cates Memorial Speedway (ECM) after Eric died in 2015—hosted the first Forestry 40 race and logging equipment show. Chris and his partner, Kelly Crawford, owner of K&K Logging, Inc., in Hanceville, organized the event, in which 14 drivers competed for $5,000 in a 40-lap single heat around the 3/8-mile track.

“We handle the race and Kelly handles the equipment show,” Chris says. “It did pretty good on short notice for a first time. Now since everybody knows, we are going to try to do it every year.” The next Forestry 40 is tentatively planned for June 2021; they want to space it out some from the MidSouth Show in Starkville, Miss., in September this year. SLT On March 21, 2015, a Saturday morning, a pair of turkey hunters was walking behind the abandoned Empire School in Walker County, near Sumiton, Ala., when they came upon a grisly discovery: a burned-up Chevy S-10 pickup, its white paint blackened with soot. Their initial thought: might be insurance fraud. Then they peeked inside. What they saw must still haunt them: the charred skeletal remains of Eric Cates and his best friend, a bulldog named Gypsy.

The younger Cates son was taken from his parents and his brother just shy of his 33rd birthday. The night before, he’d been planning to attend a barbecue with people he must have thought were his friends. Eric and Gypsy can be seen in that white S-10 on security camera footage at the Blue Store, a service station in Empire, that Friday night, talking to people who later claimed to have no memory of having seen him.

“It was awful,” Chris reflects on his brother’s murder. “I guarantee you couldn’t find anybody in this country that would have a bad word to say about Eric. But, hell, all of us have our own problems. He got to messing around with the wrong crowd. Those boys over there, with that dope, well, they just don’t have a conscience. But I don’t think it was planned, I think it happened and then they panicked and tried to cover it up.”

Premeditated or not, the act was savage. Tobbie believes Eric was stabbed first and had lost too much blood to escape. She also thinks they’d already killed Gypsy before starting the fire. “The window was down. She was very protective of Eric, but even animals have that selfpreservation instinct. When the fire started, Gypsy would have jumped out, had she been alive.” A possible scenario: Eric got into a fight at the barbecue. Always protective of her human friend, the dog attacked and bit one of them, so they killed her, stabbed Eric, robbed him, loaded them in the truck, drove them to the school, set the truck on fire with them in it, Gypsy dead, Eric perhaps unconscious but still breathing as his body started to burn. The killers then threw their own bloodsoaked clothes into the fire, hoping to destroy the evidence. A button from a pair of Wrangler jeans was found in the ashes; Eric never wore Wranglers.

He did often wear a cap given to him by a Caterpillar salesman. Evidently he was wearing that Cat hat the night of his murder. In subsequent days, someone else was seen wearing it around town. This individual, according to one dubious account of events by a purported witness, was at the party and took the hat from Eric after he was stabbed. The hat was later said to have been burned in an apparent effort to destroy evidence.

That dubious account came from a letter someone sent to the Cates family. While it names people and gives a version of what happened that night, they’ve determined that much of it is false. “There was no mention in the letter of Gypsy, and I found that odd,” Tobbie says. They believe the letter was meant to misdirect from the truth.

Though it may have been a mix of truth and lies, curiously, the letter never seemed of much interest to in vestigators. Almost from the start, Tobbie and Wayne butted heads with the Walker County Sheriff’s Dept. over the investigation. It seemed to them that the crime scene wasn’t handled properly; they say evidence, even bones, were left in a mud puddle, the truck was left out in the rain for months. “People they should have

been interviewing, they weren’t,” Tobbie laments. “It looked like the case wasn’t being worked. They kept putting us off. We couldn’t get a complete autopsy report, we couldn’t get the toxicology report. A lot of the people had been giving information to us, we’d give it to the sheriff’s department and they wouldn’t follow up on it.”

Frustrated, the family went to the DA in September 2015. According to Tobbie, he told them the only thing in the autopsy of any significance was that there was soot in Eric’s lungs, in dicating that he had been breathing when the fire started. Whoever did this burned him alive. But he wouldn’t let them see the report. Tobbie asked, why? “He refused to answer. That made us more suspicious. He just said he was not going to tell us, he did not say why. That is the kind of stonewalling we got and it only continued to get worse.”

She is convinced police were covering up for someone, protecting someone. “It goes deep,” she believes. She contacted the office of the Alabama Attorney General, Luther Strange at that time, but found no help there either. “We were at a standstill. We had all this information but no one to give it to. This went on for a couple of years.”

Sometime later, a local man named Randy Hicks was arrested on unrelated charges. Allegedly, Hicks was there when Eric was killed. While in jail, he told multiple people that he wanted to turn states’ evidence and tell the truth about Eric’s murder. No one ever took his testimony; he was quickly released and promptly disappeared. His brother found him dead in the woods weeks later, his body too decomposed by the elements to reveal a cause of death.

Hicks’ was not an isolated incident. Several others have come forward with information to Tobbie, only to disappear or die soon after, she says.

Tobbie, too, has received both subtle and overt attempts at intimidation, aimed at silencing her, at persuading her to stop rocking the boat. Early on, after a routine oil change, her car caught fire on her way home from work on Highway 280 in Birmingham. When she confronted the oil change shop, they told her the man she said did her car had never work ed for them.

Investigators kept trying to tell her that Eric’s death was a suicide or an accident. But she kept asking questions, kept pushing, and soon found herself apparently being followed and surveilled by Walker County law enforcement vehicles, both marked

Father and son were buried side by side; at bottom, Wayne on the left and Eric on the right, each is pictured on the back of their headstones with their log trucks and Eric with his dog Gypsy, who died with him. Gypsy was Eric's faithful companion in life and in death. Left: an angelic boy and his dog

and unmarked. The Sheriff’s Dept., she says, also reached out to her pastor, asking him to convince her to drop it. He told them what he knew: that telling her to shut up would only motivate her to turn up the volume.

Then Wayne fell ill in 2016. Tobbie and her ex-husband had reconciled by this point, but his struggle in this life ended a year and a half after Eric’s death. “Everything was put on hold for several months as he suffered with esophageal cancer,” Tobbie relates. “We focused then on him and what he needed. After he died, I picked it back up.”

Context

Alabama generally has a higher violent crime rate than other states for its size. If it fell within the national average, a state with the population size of Alabama should have around 220 murders on average per year (roughly 5 murders per 100,000 people, times a population just north of 4.9 million people). But, in 2016, Alabama had the third highest per capita murder rate in the U.S., with 407 violent deaths categorized as murder or manslaughter.

No surprise, much of that crime stems from the illegal drug epidemic plaguing rural America, and Walker County, a largely rural area north of Birmingham, seems to be one of the epicenters of that epidemic. While there are plenty of good people here, the county has a fairly well known reputation in this part of Alabama as a cesspool for the illegal drug trade. And it has a long history of unsolved murders and mysterious disappearances, at a rate higher than that of much larger, more urban areas.

Rumor has it that in some areas where it has gained a foothold, the meth mafia may operate in cooperation with and under the protection of local law enforcement. The scam is an old and obvious one: cops arrest the competition and look like heroes, while the real system remains un touchable. Small town cops with big time political ambitions brand themselves as law and order candidates, tough on crime…but it’s all smoke and mirrors. The cops turn a blind eye to the bigger criminals. Could this hypothetical scenario be part of the problem in Empire or other parts of Walker County?

In March 2021, it will have been six years since Eric and Gypsy were murdered, and still no arrest has been made. Justice delayed is justice de nied. Eric’s death was tragic in any circumstance; the subsequent failure to bring his killers to justice makes it an ongoing tragedy. That tragedy would only be compounded if it turns out, as Tobbie suspects, that that failure is, on some level, not entirely unintentional.

In Hamlet, Shakespeare wrote that something was rotten in the state of Denmark. It smells like something may be rotten in the county of Walker. Some things look fishy; it’s why Tobbie fears some members of local law enforcement may have mishandled the investigation, perhaps even by design.

So what gives? Is this a story of honest cops doing the best they can to bring down an entrenched system of organized crime when no one will talk? Or a story of crooked cops protecting a corrupt system to ad vance their own agendas?

New hope came with a new sheriff two years ago. An article dated

September 29, 2019 in the local

Daily Mountain Eagle newspaper announced that recently elected

Walker County Sheriff Nick Smith had hired retired investigator Mike

Cole to look into cold cases, including missing persons and unsolved murders. Eric’s case was mentioned explicitly in the article, and Smith and Cole seemed to be actively trying to help. But for the Cates family, after some early encouragement, nothing seemed to come from it.

There is a theory that Eric may have been an informant for police, or at least that some of the wrong

people might have believed that he was. It seems many of those mixed up in the drug underworld in Walker act as informants, usually giving only trivial information to earn a “get out of jail free card.” Might the brutality of Eric’s murder, a sickening public spectacle, have been intended as a warning to other informants?

In 2019, Tobbie and Chris met Amber Sitton, host of the Secrets True Crime podcast, and her partner, Michael Fleming, a retired Marine and licensed private investigator of the firm Echo 7 Foxtrot, LLC. Tobbie says other true crime podcasters had contacted her before, but this one felt different. “I wanted to see where they were going,” she says. “As the months went on, I saw that they were really working and diving into this. It has just been a godsend. The work they have put into this, and have not charged us anything, has been absolutely wonderful.”

Eric’s case became the subject of season 2 of Secrets True Crime; find it online to hear a thorough exploration of the story in all its twisted details. “When we first started talking to them they thought they’d get three or maybe five episodes out of it,” Tobbie reveals. “They got 13.”

The story has also been featured on season 3, episode 9 of the TV series “Still A Mystery” on the Discovery Plus streaming service.

Sitton is convinced that the irregularities in the investigation were intentional, not incompetence. “I hate to say that, because I’m in general a huge supporter of law en force ment,” she stresses. “But be cause of that I want it to be done right.” Naturally; when we place our re spect and trust in authority figures, it makes it all the more offensive if that trust is abused. But Sitton says there can al ways be a few bad apples mixed in with the good. “There are bad people and good people in Walker County, but the good ones are being mistreated. The victims and their families are scared to stand up and speak out be cause of threats and retaliation if they talk too loudly.”

Since the podcaster and private detective started digging into the case, Sitton has received her own fair share of veiled threats and harass ment. The bad guys seem less inclined to directly confront Fleming, a former USMC gunnery sergeant. Instead, he received word that someone claiming to be from the Walker County Sheriff’s office had called Quantico requesting information on Fleming’s service record, ostensibly in connection with a criminal investigation. It seems they basically wanted dirt on him; had he ever been investigated for anything in his career as a

Marine? The caller was directed to send the request formally to NCIS, but such a request was never filed.

In 2019, local news reported that Walker County had turned the case over to the Alabama State

Bureau of Investigation. Those claims were apparently false; SBI had not been working the case at that time. Walker County Sheriff’s

Dept. has since been taken off the case by Alabama Attorney General

Steve Marshall, Tobbie says. The

AG’s office has taken over and assigned a state in vestigator to

Eric’s case, coordinating locally with the Chief of Police for the city of Sumiton, TJ Burnett. “He seems to be a very upstanding, honest chief,” Tobbie says. “He is an exam ple of what a good law en force ment officer should be, and that is something that has been lacking in Eric’s case.”

The Secrets True Crime podcast did what it should do, Sitton thinks: it helped. “It brought attention, interest, awareness. It’s hard to ignore it with public pressure.

That’s what was need ed, so it served its purpose.” She hopes and expects to post a follow-up podcast episode reporting on multiple arrests related to Eric’s murder and its cover-up in the hopefully nottoo-distant future.

If that does happen, it will be be cause this grieving mother refused to back down, stay quiet or let it be.

Un til they give her justice, she’ll give them no peace. SLT

If you have any information about this case, plese contact Sumiton Police Chief Burnett at 205-648-3261.