42 minute read

Southern Stumpin’

By David Abbott • Managing Editor • Ph. 334-834-1170 • Fax: 334-834-4525 • E-mail: david@hattonbrown.com

Big Numbers

If you check out the top center of page 4, just under the logo, you may notice that this is the 600thconsecutive issue of Southern Loggin’ Times. At 12 issues a year, simple math tells me that with this issue, we have completed 50 full years of continuous publication.

I say “we”—I’m not quite 44 as of writing this (I might be by the time you read it; my birthday is in late September)—so obviously I wasn’t around when the first issue came out. In fact, as you might imagine, not many people are still here now who were here then, but there are a few who have been here for every single issue and, God willing, will remain with us for quite a few issues to come.

I won’t say more about it now: next month is the celebration. The first issue came out in October 1972, so we’re marking the golden anniversary in October 2022, our 601st issue and the start of our 51st year, and hopefully of our next half century. We’ll be taking a look back on the last 50 years of logging in the South.

If you’re an advertiser (and hey, we don’t exist without advertisers) or a reader with a long history in the business, we’re inviting you to participate in the anniversary issue, and there’s still time. See the ad on page 31, and contact me or one of our ad sales reps to find out more.

See you here next month!

Music Man

Now it’s no secret that I am a great lover of all types of music, from all genres and eras. But no other sound is as deeply embedded in my heart and soul, nor as sweet to my ears, as good old traditional country.

For generations, country music has provided the soundtrack, not just of the South, but for rural, small town, blue collar, working class people all over. And contrary to popular myth, it’s not all about honky tonks, heartaches, cheating and drinking. It’s also about family and hard work. There are a ton of country songs about cow boys and rodeos, farms, tractors, truck drivers, and trains. One rural profession rarely represented in country music: logging and saw mill ing! But we know our industry is a big part of the country life, always has been and always will be. So it should come as no surprise that a logger could make a great country singer/songwriter.

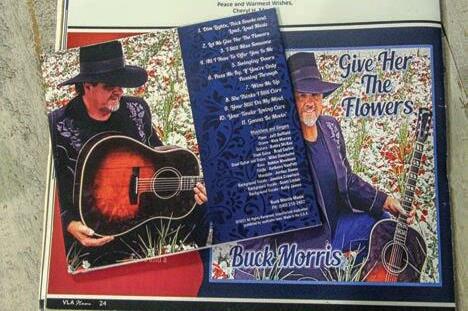

Folks in Virginia may recognize the name Buck Morris, member of the Virginia Loggers Assn. Board of Directors. A lot of people don’t even know that his real name is David Glen Morris, Jr. Buck is a nickname from his childhood that has stuck with him throughout life. When he first started playing music with a friend at school in the fifth grade, the first two songs they learned were “Folsom Prison Blues” by Johnny Cash and “Act Naturally” by Buck Owens and the Buckaroos. One of his schoolmates— who coincidentally had the last name Owens but was no relation—started calling Morris “Buckaroo.” Gradually, everyone knew David as Buck Morris. In his day job, Buck, 63, along with his brothers, runs Glen Morris and Sons Logging Inc. Timber is a family tradition. Their grandfather started farming and cutting pulpwood in the Depression; their dad left the farm for logging in the ’50s, starting the company his sons still operate. Buck grew up helping in the woods around school and sports. Much to his mother’s dismay, he joined the crew full-time in 1981, followed by his younger brothers as they came of age.

All three brothers have the same initials, and all three are better known by nicknames (much like fellow Virginians Binky and Guke Tapscott at Tigercat dealer Forest Pro; nobody knows their real names either). Middle brother Donald Gillium is called Gill, while youngest Morris Danny Gene goes by Dean. Buck and Dean run the business today; Gill retired five years ago due to arthritis.

Music is in their blood as much as sawdust; there were musicians on both sides of the family. Buck’s dad played guitar for fun and taught him chords when he was 10. He met his late friend Billy Hahn, who also grew up in a musical family, and they started playing together at school and church camp, and soon enough were getting paid to perform at birthday parties. “We were on the road before we had a car,” he chuckles.

Along with acoustic guitar, Buck learned many instruments. He started playing mandolin at 17 and banjo at 18, and in his 20s picked up pedal steel guitar. Lead guitar is his favorite thing to play in a country band, while in bluegrass he prefers mandolin.

Buck’s dad always had country playing in the truck on AM radio or 8-track tapes. He grew up listening to all the greats of that generation: Buck and Cash, but also Haggard and Jones, Patsy Cline, Charley Pride. As he grew into his young adult years in the early ’80s he became a big fan of Ricky Skaggs. “I followed him religiously because he was bluegrass, then he did country,” Buck recalls. “I actually followed him so much I would sneak back stage and he would recognize me. He would come across and say ‘Hey Buck’ and stick his hand out. I wanted a job in his band so bad, but I wasn’t that far along in my picking at that time.” Randy Travis was another ’80s hit maker who impressed him, along with Alan Jackson, who championed traditional roots in an increasingly pop/rockoriented landscape. “He’s amazing for what he did at the time he started; when you listen to his stuff, it still sounds like country music.”

Like most country music hopefuls, Buck went back and forth to Nashville in the ’80s, and considered moving there, hoping to find a big break. He was also a member of the National Songwriters Assn. for many years. He had friends who worked at Opryland, one of whom won Star Search in 1994.

At only 26 Buck was told he was almost too old to get a record deal. “It was enough to scare me, and I knew I had a paycheck at home,” he says. Still, a producer encouraged him to write songs. “I chose to join the songwriting association and went down every six months, but really I needed to be down there once a month or better, so people recognize you. If you’re gonna do it, you had to go live it; you can’t phone it in from home, you have to be here.”

As he got older he focused more on logging and made fewer trips to Nashville but continued to play in various bands, playing bluegrass festivals around central Virginia on weekends. When the line dance craze hit in the late ’80s and early ’90s, he joined a country act backing up a little girl from Fredericksburg who got publicity singing Patsy Cline songs after the biopic Sweet Dreams came out. She had a booking agent who set them up to play conventions from Delaware to North Carolina.

He worked in the woods during the week and performed on weekends. “I would leave to go to Maryland to play these clubs on Thursday evening and I felt guilty leaving my dad and brothers,” Buck confesses. “But they always got along without me.” With his calendar full, he put off getting married till 1996. Until 2017, Buck

was still always in a band; his last one was a bluegrass group that performed regionally, from Maryland down to North Carolina. Last year, Buck used his own money to make a lifelong dream come true. He recorded and released his own album: Give Her The Flowers, a collection of covers of some of his favorite songs by the artists who influenced him. Engineer Robbie Meadows of Hazzard County Recording Studio produced the album, which took about a year to complete between 2019 and 2020. On the album cover, Buck is pictured with a 1950s Gibson his dad bought in a pool room in the ’60s. “I dragged it to school and played it till it couldn’t be played, and had it reconditioned a few years ago.”

Including the title track (a Lefty Frizzell tune), the album includes Buck’s takes on 11 classic country songs originally recorded by the likes of Johnny Cash (“I Still Miss Someone”), Charley Pride (“All I Have To Offer You Is Me”), George Jones (“She Thinks I Still Care”), Merle Haggard (“Swinging Doors”), Verne Gosdin (“Gonna Be Movin’ On”) and of course, Buck Owens (“Your Tender Loving Care”).

I am a huge Merle Haggard fan, and I can honestly say I prefer Buck Morris’s version of “Swinging Doors” to Hag’s—that might be blasphemy, but I really like it. The whole album is good. If you’re, like me, a fan of traditional country, and want to support a fellow logger doing something cool in his off hours, I highly recommend you order a copy. If you know anyone who loves this style of country, this would be a good Christmas gift, too. Contact Buck directly to order a CD: text or call him at 540-219-2462.

Soon Buck will also be a featured guest on an upcoming episode of the podcast “Talkin’ Country with PopPop,” which is available on iHeartRadio’s podcasts (www.iheart.com/podcast/53-talkin-country-with-poppop-96876486/) and Google Podcasts.

Eventually, Buck might record another CD, this time of original, Buck Morris-written songs. If so, maybe he can give us a song about the heartbreak and hardships inherent in harvesting and hauling wood products. If he does, you can bet I’ll be in line to hear it.

One-Bullet Barney

Barney Fife himself attended the Carolina Loggers Assn. Annual Meeting. Nash ville based entertainer Rik Roberts (https:/rikroberts. com) worked the crowd in character, and performed on stage as a stand up comic and musician. Dewayne Woodard

We’re safer than we used to be, but logging continues to be the most dangerous job, and accidents can happen to anyone at any time. Sadly, we have another re mind er of this fact: we lost a member of our community a few months ago. A couple of years ago I saw an article in the Carolina Loggers magazine, written by former CLA Director Ewell Smith, about North Carolina logger Dewayne Woodard of Bryson City. I thought Woodard would be a good fit for an article in Southern Loggin’ Times, so I reached out to Ewell to make contact with the logger. We weren’t able to get together then, so I tried him again this spring, thinking I could visit his crew on my way up to the Richmond Expo in Virginia on May 20. I left a couple of voice mails but never heard back from him.

A few weeks after Richmond, I got a call back from his recent widow informing me that Mr. Woodard tragically died in a logging accident May 17, 2022. That was the Tuesday before Expo Richmond; I was traveling in the region, and if we’d been able to connect, I very well might have been in the woods with him that day.

Since we were never able to feature him in SLT while he was alive, I felt obliged to acknowledge him now. Unfortunately, and I hate this, I no longer have the phone number Mrs. Woodard called me from, and of course the cell number I had for him is no longer in service, so I was not able to contact his family. However, Jonzi Guill, CLA’s current director, provided me with some photos, and I was able to find his obituary online.

Dewayne Larry “Pedab” Woodard, 47, was the owner of Woodard Logging, LLC. Woodard was a native of Swaine County, with the family business based in Alarka. His parents were Betty and the late Larry Woodard. He and wife Megan Biggs Woodard had two children, Drew Ann Woodard and Zackary Dewayne Woodard, as well as various nieces, nephews, and special children Silas, Piper and Paislee Stanberry and Maverick Biggs. Dewayne had a sister, Vicki Davis, and a brother, Chad Woodard.

Like probably most loggers, Mr. Woodard was said to love the outdoors: hunting, fishing, boating. He also loved baseball and coached youth in the sport.

According to local news reports, Dewayne and Chad were working together on a tract in Jackson County, with Dewayne felling and Chad driving a skidder. There was apparently some dead wood hanging over the spot where he was cutting; evidence indicates that the deadwood fell and struck Dewayne, causing a fatal head injury. Chad got off the skidder and found his brother on the ground.

Funeral services were held on Saturday, May 21, and he was buried at Mason Branch Cemetary. SLT sends our condolences to Mrs. Woodard and the rest of Dewayne’s family.

When we profile a logging business, we want to tell that logger’s story, as he sees it, and we aim to be as thorough and accurate as we can be in just a few pages. That’s the goal, anyway. We’re limited by time and how much room is physically available. Often some interesting parts of the story end up on the cutting room floor, so to speak. Still, when we do become aware of a mistake or an omis sion, we strive to do whatever we can to correct it (difficult once it’s printed in thousands of copies).

In this case, all I needed was to give a guy a little more space. In our August issue, we highlighted Thomas Johnson, 33, of DeRidder, La. There wasn’t room for his complete story last month, so I wanted to use the extra space I had available this issue to fill in what was missing.

An important context: last October, Thomas was diagnosed with a giant cell tumor in his back. He was in severe pain and hospitalized for treatment for months, three hours from home. The diagnosis came just a few months after Thomas started his company, Cutting Edge Logging.

Thomas got by with more than a little help from his friends/family, but last month’s article was vague as to who specifically. He wanted to make sure they got public credit, and I’m happy to oblige.

Three men kept the business alive: Thomas’s cousin Mickey Townsley, Cutting Edge crew foreman/loader man; another cousin, Brady Johnson, and Thomas’s dad Tommy Johnson, Sr., who tagteamed felling while still working their own fulltime jobs elsewhere.

“Mickey was the one who kept the operation going,” Thomas says. “He kept things moving with his expertise from running jobs for our uncle and his years of experience. He did what needed to be done and kept it moving without missing a beat.” But Mickey’s not a cutter operator, and someone had to fill in on the feller-buncher while Thomas was in the hospital. Tommy, Sr., and Brady stepped up to that plate. The elder Johnson juggled that with running his own company and visiting Thomas in a Houston hospital as much as possible. Brady also cut timber for another logger, but after hours he would head to the Cutting Edge job. Since then, Brady has joined Cutting Edge full-time.

Thomas is also eager to express his appreciation to Bennett Timber Co. and Hancock Forest Management. “They could have said, ‘You’re only six months in and we really don’t feel comfortable going forward with this major health diagnosis,’” Thomas acknowledges. “But they really worked with me to keep everything going. That was big.”

It’s also worth noting that Thomas is actively in volved in the Louisiana Loggers Assn. and American Loggers Council. “I’m just trying to be a positive voice for the logging industry as a whole,” he says. He serves as a board member for LLA and has been tapped to participate in a panel at ALC’s Annual Meeting in Branson, Mo. in September.

Like many young loggers of his generation, Thomas has been active with things like YouTube and TikTok, posting videos of his equipment in action. Initially he was just sharing it for fun. But he came to see it as a tool that could help educate the (generally misinformed) public. He wants to explain what loggers do, and how and why, and help those outside the industry understand the value and essential service loggers provide for society. It serves a purpose, not just to draw attention to himself. “It’s not meant to say ‘Look at me,’” he stresses. “It’s, ‘Look at us.’” SLT

High Rise

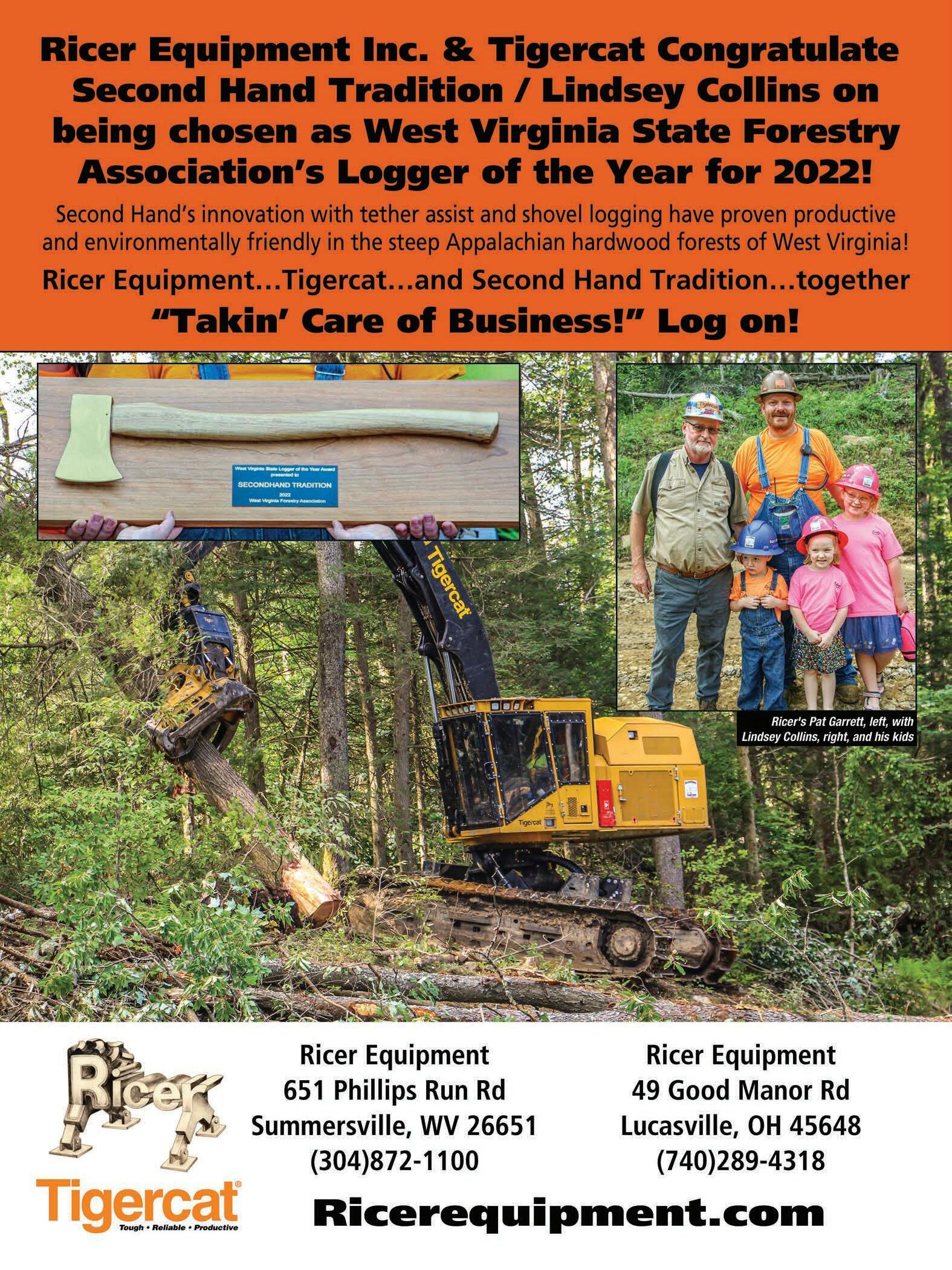

■ WV’s 2022 Logger of the Year, Lindsey Collins, tries tethered logging in steep Appalachian slopes.

By David Abbott

BIRCH RIVER, W.Va.

Company hats for logging entity Secondhand Tradition Ltd. feature on the front the company’s logo, a simple image pregnant with meaning. It illustrates one hand handing a double-sided ax to another. On the back of the cap, an explanation is printed: “From Dad’s Hands To Mine.” A graphic designer created the logo from an actual photo that was taken when the dad in question, Roy Collins, gave his son, Lindsey, an ax that had belonged to his grandfather, Cecil Collins. It was a symbolic passing down of the family tradition from one generation to the next, memorialized in the company’s name and logo.

Lindsey Collins, 43, the owner of Secondhand Tradition, is a fifth generation logger, and by all indications, he’s doing right by his family’s legacy. He started the company in 2006, but the last year has been a big one for him. For one thing, he just finished his first full year operating a winch assisted tethered system, allowing him to harvest timber in steep terrain that would be otherwise inaccessible by conventional means. He decided to give it a try last year; by all accounts, the experiment has been a success so far.

Along with that, this summer West Virginia Forestry Assn. recognized Collins as West Virginia’s Logger of

This summer, Secondhand Tradition owner Lindsey Collins (here with his dad, wife and kids) was named West Virginia's Logger of the Year for 2022.

the Year for 2022. Those who know him have no doubt the honor was well deserved.

For instance, there’s Pat Garrett (presumably not the one who killed Billy the Kid). A salesman at Ricer Equipment, the Tigercat dealer in this territory, he has a long and mutually beneficial relationship with Collins. “He’s come such a long way,” Garrett says. “We have had ups and downs on equipment, but I have told him I will always have his back. He has been a good customer and a good friend. He comes from a good family. His wife homeschools their kids. He is a good Christian oriented guy; if we had more people like him out there it would be a better world.”

Home Run

Collins started using the tethered system in August 2021. “We are running out of mechanized feller-buncher ground,” he says. “We’ve had the feller-bunchers on the land for 25 years and we’ve caught up to the ground they perform well on. So we had to go to something (different) because Weyerhaeuser is big on no power saws and they don’t want people on the ground, they want to try to do it as safe as they can.”

Last spring, Collins went out west, to Oregon and Washington, to watch this technique in action. Ricer’s Garrett accompanied him on the trip to learn about tethered logging. “We put it on paper and agreed that tethering with a bogie skidder and an 855 (track cutter), he could harvest ground that would be impossible to harvest without roading the heck out of it,” Garrett recalls. “It was just too steep to log conventionally. But we could tether it where Weyerhaeuser needs it harvested. That way he has been able to harvest safely and mechanically with no one on the

Secondhand Tradition targets high-value timber in hard-to-reach terrain, especially high elevation tracts.

Last year Collins modified his excavator with a winch to serve as an anchor tethered to skidder or cutter on steep slopes.

Crew, from left: Ryan Leonard, Lindsey Collins, and brothers Dwayne and Tony Deal; not pictured: Derrick Bennett, Steve Tinnel, Thomas Collins, Steve Wolverton Truck driver Dawson Hannah; not pictured, drivers Junior Mathes and

Justin Armentrout

Southern Loggin’ Times l SEPTEMBER 2022 l 11

ground. The 855 really shined with the tether.”

Collins adds, “We decided that was the way to go, and it’s been great. Now we do jobs we wouldn’t even look at before. We’ve done jobs they’ve had laid out for 15 years, but we didn’t do them because they were too steep and too rough.”

Skidding downhill is really pretty revolutionary in West Virginia, Garrett says. “The state forester agreed to let him try this type of harvesting, and it has left the ground in much better condition than it would have been if he conventionally logged it. There is just minimal soil disturbance.”

Secondhand Tradition uses a John Deere 350G LC excavator as an anchor. The excavator rests on stable ground, positioned with the boom facing the slope, downhill, and winches the cable down to either the cutter or skidder, alternating one at a time. Collins is considering getting a second winch/anchor machine set up so they can tether cut and tether skid at the same time.

Collins already had his excavator years before he started tethering. He bought the 2015 model Deere from Leslie Equipment in Cowen, W.Va. Last year he removed the counterweight and shipped the machine to Kelso, Wash., for winch supplier Summit Attachments and Machinery to add the winch and extend the boom 16 ft.

“(Summit’s Eric Krume) went through all the pains of building and rebuilding these to learn where they needed to pull,” Collins says. “You would think the tether would pull the machine over the hill. But the more weight is put on the tether, it actually pushes the machine further down in the ground. It gets more stable.”

This technique requires skill, and practice. “I don’t think I knew what I was doing when we first brought the tether here,” Collins admits. “But I had seen enough jobs that I felt like we could make it run.” A big component of that confidence was the support from Eric Krume at Summit Attachments. “He’s a super good guy. He comes with the machines and spends a couple weeks with you while you work. He’s a logger himself and makes sure you perform well.” The first tethered job the crew tackled was a tract called Big Run 2. “(Krume) came with us to get us started and didn’t leave until we were comfortable with what we were doing. I would say it was a home run, in my opinion, for the first job.”

Lindsey and wife Megan Collins (right) with Weyerhaeuser's "Mountain Laurel" Kemmerling at the Turkey Creek veneer yard

Aside from the Deere excavator and a John Deere 850K dozer, Secondhand Tradition uses all Tigercat machines in the woods: two skidders (’21 model 620H and ’22 model 625H), ’21 model LS855 track cutter, and two 250D loaders, ’15 and ’21 models, one with a longer boom with a high rise cab. “I have a good relationship with both dealers,” Collins says of Ricer Equipment (Tigercat) and Leslie Equipment (Deere). “Most of them are my friends; Pat is like a buddy of mine. Even their mechanics are our field techs but also your buddies at the soccer field.”

Secondhand Tradition has used Tigercat since Collins started the business in 2006. He was not the first Tigercat logger in West Virginia, but he thinks he was one of the first, and maybe the second in the state to buy a Tigercat log loader. “They didn’t have much of a dealer network then. We bought ours from Lyons right before they went out of business. So for a while we had some equipment with no dealer.” During that time he bought parts from a dealer out of state. “Thank the Lord, with Tigercat I didn’t need a lot of parts. Tigercat makes outstanding logging equip-

Collins has a strong relationship with Tigercat dealer Ricer Equipment. The family: Lindsey and Megan, center, with Lindsey's dad Roy Collins, left, and Megan’s mother Kay Wood, right; and out front, the kids: Lincoln, Madison and Lorelai

ment, I think because they’re a logging based company.”

The logger purchases a PM agreement on most machines, letting the dealers handle it under warranty. “We just keep them fueled up and greased and turn the rest over to them,” he says.

Collins runs all his own trucks, a fleet of Peterbilts from 2007 to 2020 models, pulling Pitts trailers. Drivers include Dawson Hannah, Junior Mathes and Justin Armentrout. Setout trucks are old Autocar and Internationals.

(Less Than) Zero To Hero

Garrett likes to say that Collins went from less than zero to hero. About 10 years ago, not long after Collins and his former partner went their separate ways, the young logger, completely on his own for the first time, found himself in a tough spot (even by loggers’ standards).

“He was logging in some really rough mountainous ground in Wyoming County, and discovered that he had some debts he wasn’t aware of,” Garrett relates. Embarking on his solo career, Collins found himself starting out deep in the hole with debts he didn’t even know he had, not to mention the usual high operating expenses, like insurance, equipment and fuel.

“He had less than nothing in the bank, went to Ricer Equipment in Lucasville and bought a used Timbco and an old Cat skidder, and started off with less than nothing,” Garrett says. “He worked six and seven days a week and hustled with that used equipment, got some good help, started making some money and really did go from less than nothing to something because of his

work ethic. Also, Lindsey is intelligent. He started with an overdrawn bank account and worked his way out of it and he has been a hero to his family.”

Lindsey and his wife Megan met at church and married in 2005. They have three kids: Lorelai Kay, 7, Madison Grace, 5, and Lincoln Roy, aka “Little Chief,” 4. The family attends Mountain State Baptist Church in Summersville.

Everyone on the job wears appropriate PPE, including high visibility shirts, with names printed. Some of the hardhats are marked as “Roy’s Boys,” a reference to Lindsey’s dad, Roy Eldon Collins, 86. Roy spent his career working for his own fa ther, Cecil. Both Lindsey’s great grandfathers worked for one of the first sawmills in the area.

When he was 13, 30 years ago, Lindsey says he was always bigger than most people; he could skid logs and load his LTL9000 picker truck by himself by that age.

After finishing school, Lindsey drove a contract log truck for his brother James for almost five years. He saved his money and in 2002 bought his own truck. In 2006 he partnered with a family member to start logging. He rented a dozer from Leslie’s Equipment and bought an old loader and skidder from Garrett. After about a year the partners were able to trade for new Tigercat machines. They split amicably in 2012 when Lindsey’s partner went into a different field of work, and that’s when Lindsey had to rebuild.

Production

The crew was working on Weyerhaeuser land when Southern Loggin’ Times visited in midAugust. Secondhand was delivering veneer logs, in this case all wild cherry, to the Turkey Creek veneer yard, a Weyerhaeuser staging area adjacent to the tract, at the bottom of the hill. “Every main port to their land, they have a yard at the mouth of it to handle their veneer,” Collins says. Weyerhaeuser timber buyers Laurel “Mountain Laurel” Kemmerling and Dan Abston were working on the log yard, scaling logs unloaded from Secondhand’s trailers. “Our set out trucks bring the stuff out of the woods and drop it so on-theroad trucks don’t have to wait or go so far off the beaten path.” Weyerhaeuser takes the veneer logs (cherry, hard maple, curly soft maple and various oaks) from here. Secondhand hauls chip wood to Weyerhaeuser’s OSB mill in Flatwoods (Heaters), W.Va. Saw logs go to Laurel Creek Hardwoods in Richwood, W.Va. Hayes Scott Fence & Lumber in Mill Creek buys their softwood. Pine pulp, hickory, locus and hemlock go to the WestRock mill in Covington, Va. The crew produces an average 45 loads a week.

The good thing about timber left in these steep slopes, Collins says, is that no one has been able to get to it for 30 years, so it’s where higher quality wood is. “The benefit to doing steeper, rougher ground, you are actually getting better timber. You are getting high value veneer logs.”

Collins estimates the crew averages 70% OSB chip wood and 30% saw logs or veneer. “The flip of the veneer is up to the buyers,” he notes. “Sometimes they might take half of that 30% for veneer, but this time of year, the sap is up. Mainly what we do is even age management or clearcutting when we run that ratio of 70% pulpwood to 30% logs; that’s actually a pretty good tract if we can still get 30% saw logs.”

The crew works almost entirely in hardwood. “Our pine in West Virginia only runs in high elevation, 3,500 ft. and up,” he says. The job Secondhand Tradition was working when SLT was on-site pushed 3,900 ft. Here they cut some hemlock and red spruce for fence rails.

Collins believes this July may have been the wettest on record, and it showed, even on the high ground. “In this high elevation, there shouldn’t be standing water. About the last six weeks we have had horrible rain. If we hadn’t been tethering it would have been a very low production summer but since we were tethering we were able to keep producing.” SLT

Multitasker

■ Ken Hodges has his hands full with his multi-crew operation—and that’s just the way he likes it.

By Tim Cox

SOUTH BOSTON, Va.

At the office and shop for H&M Logging, it is the ap pointed time for a scheduled in te rview with owner Kenneth Hodges, but he is nowhere to be found. Via cell phone, Hodges says he will arrive in 30 minutes. Another 45 minutes later, he apologizes for the delay and says he will arrive in 15 minutes.

After 15 minutes, a tractor-trailer hauling gravel pulls up in the drive way. A tall, slim man with gray hair gets out. He’s wearing a company uniform. Ken Hodges introduces himself and then walks to the mail box on the side of the road to re trieve the company’s mail.

It’s an understatement to call

One H&M crew, left to right: Tim Satterfield, Brandon Mills, Raymond Pannell, Larry Fallen

H&M Logging owner Kenneth Hodges oversees operations at one of his 10 crews.

Hodges runs a fleet of 28 rigs of various makes and around 100 trailers, including three new Pitts. His companies haul logs, chips and gravel.

Hodges a busy man. During the course of the interview in his office he is interrupted a few times with phone calls, meets briefly with his insurance agent, and signs the paperwork to buy a new skidder.

Hodges, 62, owns the company and two unrelated businesses, Hodges Farmland LLC and Cassada Farmland LLC. He says he has worked in logging for 55 years. That would mean he got started at age 7—an early start indeed. “I work every day,” Hodges affirms. “I’m a laborer as well as a boss. I don’t ask nobody to do noth ing that I don’t do, and I do it all.” Hodges has a sprawling business that currently employs 70 people. The company normally operates 10 logging crews of three men each.

He gets to the office and shop at 5:30 a.m., “sometimes earlier,” and opens up the shop. The men arrive soon after, and Hodges distributes supplies and materials for the truck

The family: Kenneth Hodges, center, with his wife, Mary, right, and to the far left, son, Kenneth Hodges II with his daughter, Nevaeh

Hodges uses several John Deere skidders, including some 2022 model 748Ls.

drivers and logging crews — hard hats, flags, hydraulic oil, DEF fluid, and so on — and sees them off. He “goes all day” until stopping work around 6 p.m.

“Right now I’m driving a truck,” he says. “I do driving, check on crews. Mainly truck driving.” Late ly he has been driving dump trucks and hauling gravel. “We’re doing more excavating work in the last two years,” he explains. The com pany is currently doing excavation work for a site where solar panels will be installed.

South Boston, home to Hodges and his business, is in the southern tier of Virginia, known as Southside Virginia. It is only about 10 miles from the North Carolina line and less than 60 miles north of Durham. On the outskirts of town is South Boston Speedway, a short asphalt track that hosts races for Late Mod el Stock Car, Limited Sportsman, and other classifications.

Growth

Hodges entered a partnership with another logger, John Miller, in 1982; the H and M in H&M repre sent the first letters of their last names. That partnership lasted for three years, then Miller sold his interest to his son, John Miller, Jr. Hodges and the younger Miller continued doing business together until 1988, when Hodges bought out his partner. Since then he has continued to own and operate the business as H&M Logging.

In 1988 he had five employees and produced about 40 loads of wood per week on 10-wheel trucks. Today the company has 70 em ployees: 10 logging crews of three men each plus two additional men who operate cutters as needed, floating among jobs to increase or speed up production; 24 truck drivers (including two dump truck drivers), three handymen, seven shop personnel (five mechanics, a welder, and their manager), a forester, and three secretaries.

Hodges likes crews to produce at least seven loads per day. “That’s 35 per week average, probably 40,” he estimates. “Some do less, some do 60. It depends on the trucks, too.”

He has two shops – with his

James River Equipment in Danville is the John Deere dealer for Hodges.

offices in one – located on 20 acres. He is in the process of building two more shops nearby; one will be used mostly for storage of equip ment and supplies, and the other will be used mainly for welding.

Family Connections

Hodges’ son, Kevin, worked with him for a few years after earning a master’s degree. “We butted heads,” recalls Hodges. He was starting to downsize H&M Logging in 2010, so he gave his son half of his equip ment to help him start his own logging business, KeJ’aeh Enter prises (which was featured in Southern Loggin’ Times in May, 2014; H&M also previously ap peared in SLT in May, 2006). Hodges only cut back his business a year. Now he is doing more work than before he helped his son get into the business. Father and son are still on good terms, and Hodges lets his son freely use one of the shops.

Hodges has another son who works with him in H&M Logging, Kenneth Hodges II. Although he can operate equipment, his son’s role is mainly administrative; he oversees the company’s safety pro gram and orders parts, among other things. The younger Hodges holds regular safety meetings with em ployees. When SLT visited the com pany, a notice was posted on the front door of the office building reminding truck drivers about an upcoming safety meeting with a state trooper and insurance agent.

Hodges’ wife, Mary, his partner in marriage for 43 years, handles 90% of the company’s paperwork and the finances. A granddaughter, Nevaeh, one of three grandchildren and a student at the University of Virginia, is working in the office for the summer.

Setup

The three-man logging crews are standard: an operator each for a loader, a cutter, and a skidder. “We always have one loader,” Hodges says. “Sometimes we use two cut ters and two skidders. We double up when we’re pushed for time on a tract, or if it’s a very large tract.” Hodges also will assign more men to a job if a mill pays bonuses on the wood.

Hodges keeps precise infor ma tion about his business in his head and can rattle off details.

H&M Logging has a mixed fleet of logging equipment, mainly John Deere, Cat, and Weiler machines. Hodges can give you the numbers off the top of his head. He has four Cat 559C knuckleboom loaders, one Cat 559B and one Cat 559D; he also has three Weiler K560 loaders (including a new one sitting at the shop), and one John Deere 437E.

For skidders, the latest additions are two ’22 John Deere 748L ma chines, and he bought another two of the same model almost a year ago. Hodges also has four John Deere 648Ls, two Cat 545Ds, two Cat 525Ds, a Weiler 350, and a Tigercat 630. Four older John Deere machines are used as backup skid ders: three 848Hs and one 646H.

The newest cutters are a John Deere 843L-II and a Weiler 570, both 2021 models. The company also runs two John Deere 843Ls and two John Deere 643Ls. Older ma chines that don’t see as much use include three John Deere 643K cutters and a John Deere 843K. Most of the John Deere machines are equipped with the FD43 heads while the newest machines have center post heads. For his chipping operations he has four Trelan whole tree chippers.

For logging equipment he usually turns to James River Equipment (for John Deere) in Danville, Carter Machinery (Cat and Weiler) in South Hill, and Forest Pro (Tiger cat) in Keysville. Hodges prefers to buy new equipment, although he occasionally buys a used machine.

H&M is also equipped with three John Deere skid steers (two 143Es and a 343G) that are used to move road mats and perform similar light duty tasks.

For its trucking operations, the company is equipped with 28 semitractors: 12 Kenworths, nine West ern Stars, five Volvos, one Mack and one International. He also has five dump trucks for hauling gravel.

Hodges doesn’t have a favorite when it comes to truck brand. “I try to buy the best deal. My price is my favorite. Price and, of course, ser vice. Now service is the same wher ever you go. Waiting on parts. Every body is filled up. It’s not like it used to be.”

Hodges estimated that he has “probably 100 to 120” various trailers, including those for hauling logs, chips, and equipment; about half of them are log trailers. He just recently bought three new Pitts log trailers.

In addition to his own trucking operations, Hodges uses four own er-operator trucking con tractors.

Hodges hired a full-time forester three years ago, Ryan Throck mor -

ton, a graduate of Virginia Tech. Throckmorton looks at all tracts of timber Hodges is considering buy ing, but in most cases so does Hodges. They confer on how much to bid. “I put my eyes on every tract after we buy it to set up the job,” says Hodges. He also does a lot of timber buys himself because he gets repeat business from landowners with whom he has dealt over the years.

Hodges tries to keep hauls to mills under 80 miles. The com pany’s longest haul currently is from Brookneal, Va., to the Canfor Southern Pine mill in Graham, NC.

Canfor is one of his most impor tant markets, buying most of his pine saw logs, about 100 loads per week. Pine saw logs also are sup plied to Slick Rock Lumber Co. in Nathalie, a sawmill that Hodges founded with an Amish business partner a few years ago before sell ing his interest in the business last year, and also to Hopkins Lumber near Martinsville. H&M Logging also occasionally cuts for TealJones Group, a Canadian company that operates a pine sawmill near Martinsville.

Hardwood saw logs are sup plied to Difficult Creek Lumber Co. near Scottsburg, C&C Lumber Co. in Liberty, and “some small Amish mills when they need it.” Amish people have migrated to the region and launched a number of small sawmills in the past 10 years, Hodges says.

Hardwood pulp is hauled to a Georgia-Pacific chip mill in Brook neal. More pulp goes to three OSB mills: Huber Engineered Woods in Halifax, Va., Louisiana-Pacific in Roxboro, NC, and Georgia-Pacific in Gladys, Va.

“Markets are pretty healthy,” Hodges says. “I think they’re going to be even better next year at this time.” Prices “could be better,” he admits, but are stable.

SLT visited one H&M job. It was a 200-acre tract about a 10-15 min ute drive from the office. The tract was partly plantation pine with “a lot of overgrowth chip wood,” Hodges says. “It was never really sprayed,” to keep down the other vegetation.

The job will produce about 100 acres of pine and 25 acres of

“decent hardwood.” The remaining 75 acres is “trashy” hardwood and

Virginia pine that is being chipped.

On the day of the visit, four men were working on the site: the loader operator, cutter operator, and two men operating skidders.

Hodges buys all his lubricants, oils and fluids (mostly Citgo brand products or brands compatible with John Deere specifications) from one supplier, Hutchinson

Petroleum in Stuart, Va.

He has been buying diesel fuel from the same supplier since he started in business in 1982, Foster

Fuels in Brookneal. He buys diesel by the tanker load, usually three per week, and it is offloaded and stored in tanks on his property.

Canfor Southern Pine and Hu ber Engineered Woods have “step ped up” and are paying extra to help Hodges with the high cost of fuel. However, even the addi tional amount is only enough to cover the first 40-50 miles or so. “And the fuel is still going up,” he adds.

Hodges, a member of the Vir ginia Forestry Assn. and the Hali fax County Chamber of Com merce, bought a new house several years ago. “I enjoy working in the yard, cutting trees, getting it the way I want it. That’s been my hobby the last three years.”

He works six days a week, some times seven. He’s been work ing the same kind of schedule since he’s been in business, he says.

Another task he takes on him self is moving logging equipment with a semi-tractor and lowboy trailer. He does about 80% of the moves him self, he estimates. He also uses a subcontractor, John

“Greedy” Gregory, after selling him a truck six months ago.

Hodges has no immediate plans to slow down or retire. “I just bought three new skidders within the last six months and two trucks.

I’m probably not cutting back.”

Re tirement is “no way in sight,” he says. SLT

Making The Cut

■ Oregon Tool Marks 75th Anniversary

NOTE: This article was submitted by Oregon Tool

By Jason Landmark, President, Forestry, Lawn and Garden at Oregon Tool

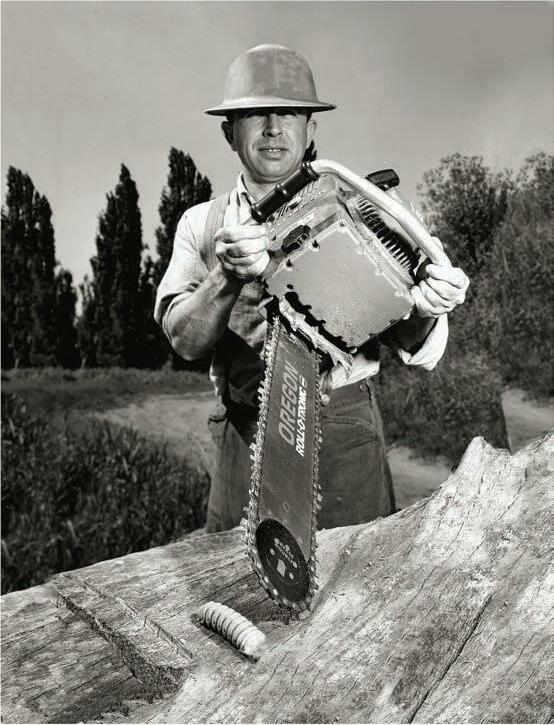

When Oregon Tool’s founder, Joseph Buford Cox, first invented the Cox Chipper Chain in his basement, he didn’t envision what the company would become 75 years later. Today, Oregon Tool manufactures the “World’s #1 Saw Chain,” and our products are sold in 110 countries. While we’re now an industry leader, our origins are humble.

As a young man, Joe set out from his hometown in Oklahoma to find work. He worked as a machinist in Colorado, a construction worker in California and a welder in Arizona and Texas before he made his way to Oregon. This was during the Great Depression, and work was scarce. Luckily, Joe found a job in logging. He learned every job in the business, felling trees using an ax or a two-man crosscut. Eventually, he was handed a new type of power saw.

While the saw was powerful, it simply didn’t work as efficiently as felling trees with a handsaw. At the time, power saws used scratcher chains, with tooth configurations like that of a handsaw. They took significant effort to operate and had to be sharpened frequently. Tapping into his industrial background, Joe knew there had to be a way to improve the power saw.

A Solution Inspired by Nature

Joe did figure out a solution, and he found the inspiration in an unlikely place. While searching for salvage timber after a forest fire, Joe noticed tiny tunnels carved into a stump by the larvae of the timber beetle. Timber beetles lay their eggs under bark. When the eggs hatch, the larvae bore through the timber with voracious precision. With their two serrated jaws, they chew through solid wood, leaving nothing but sawdust in their wake.

Joe took some larvae back to his Portland, Ore., home and studied them under a microscope. It seemed the larvae were cutting the wood in all directions, not just back and forth like a common handsaw or the scratcher chain of a power saw. Turning his basement into a workshop, Joe designed a chain that would mimic the jaws of the timber beetle—it not only changed his life, but also revolutionized the industry.

Joe’s invention became known as the Cox Chipper Chain, and it was faster and more efficient than a scratcher chain and didn’t have to be resharpened as often. He patented his chain and in 1947 established the Oregon Saw Chain Corporation, which would later become Oregon Tool. The company sold $300,000 worth of saw chain the first year, and sales reached $7 million in 1955. By 1980, the company was manufacturing products in 17 plants across five countries, employing over 4,000 people and reaching over $250 million in sales.

Today, Oregon Tool continues to manufacture the “World’s #1 Saw Chain” as well as a variety of other precision cutting tools for forestry, lawn and garden; farming, ranching and agriculture; and concrete cutting and finishing.

Sticking to Values Led to Success

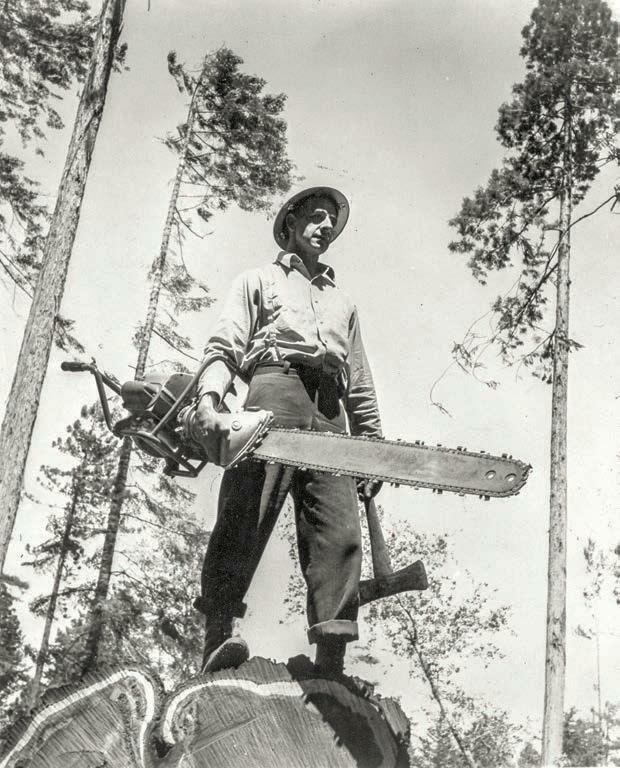

In 1947, logger and inventor Joseph Buford Cox founded the company that would become Oregon Tool in Portland, Ore.

While we’ve been celebrating our 75th anniversary, we’ve also been reflecting on Oregon Tool’s success. We know that a big part of why we’ve lasted—and thrived—for so long is because of the core values that Joe instilled in our company.

We lead with humility, and we believe inspiration can be found in unexpected places – and we’re dedicated to listening, learning and rolling up our sleeves to “get to work” together. We “own it,” which to us means that we are accountable for every action, and we do what we say we’re going to do. We are continuously innovating, and our team members around the globe demonstrate the same unrelenting pioneering spirit that Joe did. In fact, we perform 25,000 hours of product testing annually in both labs and real-world settings to ensure superior cutting quality and safety.

We also practice global stewardship and serve a higher purpose than the products we make. Through Training, Recovery, Environment and Education (t.r.e.e.) efforts, we positively impact people, communities and landscapes around the world through our global cause program, The t.r.e.e Initiative. In honor of our 75th anniversary, we’re committing to planting 75,000 trees through our partnership with Tree-Nation as a way to support global reforestation and offset carbon emissions.

Our Disaster Response Team, which brings trailers of tools and product specialists to areas affected by natural disasters, has sharpened, repaired and replaced thousands of saw chains to help relief crews do their jobs. In 2020, the team sharpened over 2,700 chains and repaired almost 500 more as it assisted in Louisiana’s cleanup efforts in the wake of Hurricane Laura. And in 2021, we headed back to Louisiana after Hurricane Ida and down to Mayfield, Ky., after a tornado, sharpening a total of 3,974 chains and repairing 615 chain saws to further recovery among those disasters. Although we don’t know where 2022 will take us, we do know our team will be ready to go and lend a hand wherever they’re needed.

From our humble beginnings in a Portland basement to being a global leader in precision cutting tools, Oregon Tool has experienced continuous innovation and growth over the last 75 years. As we consider how we will continue to serve the logging industry, we feel both thankful for and inspired by Joe’s pioneering spirit and the values he established for Oregon Tool. They’re not just our legacy, they’re our future. SLT

Bob Penberthy shows off the inspiration behind Oregon’s saw chain: a timber beetle larva.