8 minute read

Living With Hearing Loss

Educate, Educate, and Advocate, Advocate

By Pat Dobbs

Advertisement

One tip: Call the theater or meeting place ahead of time and ask about the accommodations they have made for people with hearing loss. And please be respectful if they tell you there will be a sign language interpreter available.

I grew up with typical hearing, but now I rely on my bilateral cochlear implants to hear. So although I live in the hearing world, I sometimes feel like a ghost, hanging around but unable to participate when I can’t follow conversations.

I’ve been learning how to do something about it. It’s a simple lesson that I must remind myself to keep practicing: Advocate through education with a good sprinkling of humor and persistence.

Here’s how.

When eating out.

I ask my dining companions to look straight at me when they talk, speak louder (and maybe more slowly wouldn’t hurt), and try to speak one at a time. Most of the time, my friends react positively to this—after all, they want me to hear them.

It’s a pain to remind them when they forget, which inevitably happens, but I’m getting over it. I need the education and patience as much as they do.

When in a public venue.

Interested in attending a play, lecture, or movie? What about a school board meeting? In theaters, auditoriums, and lecture halls, it’s not a question of interacting with your companions. It’s a technology problem. Many venues have not installed the assistive listening devices that have been such a boon to the hearing loss community. In this case, advocate and educate.

Call the theater or meeting place ahead of time and ask about the accommodations they have made for people with hearing loss.

And please be respectful if they tell you there will be a sign language interpreter available.

Ask if they have installed a hearing loop, which will work with your telecoil-enabled hearing aid or cochlear implant. Or maybe they have an FM or IR system. If they do, where are the devices? How often do they check or test them? You don’t want to end up at a place where the technology is present but broken or inoperable.

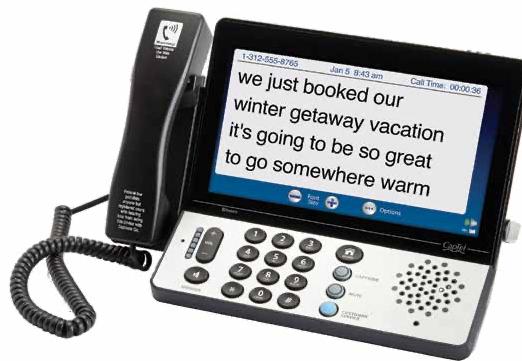

When there is a screen.

Another accommodation is captioning. My preference is open captions, where the captions are displayed on the screen so your eyes focus in one place. Some theaters and other public venues display closed captions on your tablet or phone, which is better than no captions at all, but your

focus must go back and forth.

When I go to see a play, I tell patrons around me I’m using my tablet for the captions. After all, I don’t want to create the embarrassment recently experienced by an actor on Broadway who mistakenly called out a patron with a hearing loss for using her tablet; the actor thought she was recording the performance.

When, more broadly, you need to remind folks it’s the law.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) says that public venues must provide reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities, and hearing loss is included. But there is no ADA police force—those of us who need accommodations must be the force who educates the operators of these venues, and advocate for our right to have them.

This is where you need to exercise all your advocacy muscles. And a group working together is going to be more effective than just one person making a timid complaint. After all, providing hearing accommodations requires investments in time, effort, and money on the part of the venue. Consider asking your local chapter of the Hearing Loss Association of America to get involved so you can fight the good fight, together.

Celebrate Wins

Berkeley, California, introduced curb cuts citywide back in 1971. There were plenty of opponents to this expenditure of public funds to create dips in sidewalks that allowed the smooth transition from raised sidewalks to streets a few inches below, and then back up again to the sidewalk on the other side of the street. But disabled veterans and others advocated so effectively that the curb-cut phenomenon became a reality.

And guess what? After the uproar died down, everybody realized it was in the community’s interest to have curb cuts, so they’ve become almost universal, to the joy of moms pushing strollers, people schlepping wheeled luggage, and kids riding skateboards.

Captioning is now becoming the norm across social media. Although it is still something you have to proactively enable on your TV set, if you’re on Instagram or YouTube, for instance, you’ll have noticed automatic captions are routine.

This is due not only to steadfast advocacy efforts but also because it turns out the majority of people like to watch their videos with the sound off. And that means needing the captions to follow what is happening. As a result of this demand, social media platforms have made it super easy for content creators to add captions to their videos. So we all benefit from captioning, with or without a hearing loss.

Be Seen

I have gotten thoroughly tired of being a ghost at my own party. Haven’t you? I’ve made it my mission to speak up, for myself and for our community. Speak up to your friends, your family, even your annoying uncle who just doesn’t get it. Speak up at public meetings. Educate your local officials, the guys who own the local theater, and the convention center in your city: It’s your right to have accommodation for your hearing loss.

I know you can do it, too.

Pat Dobbs began to lose her hearing in college, and when she reached her mid-50s, lost most of her hearing in both ears. She is now the proud owner of bilateral cochlear implants, and an enthusiastic advocate for the hearing loss community. She has spoken and written widely on the topic of hearing loss. In 2011 she founded the Hearing Loss Association of America, Morris County Chapter, New Jersey, and today is president of the international online hearing loss support group, Say What Club, saywhatclub.org. Having moved to Deer Isle, Maine, she is forming the Downeast Chapter of HLAA. If you are interested in learning more, email Pat at pat@coachdobbs.com. For references, see hhf.org/winter2023-references.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

A Daily PRACTICE

By Sarah Kirwan

I was 33 when I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS). I was in Los Angeles, experiencing what I could only imagine were the worst moments of my life, and I was alone. Only days later, I attended my first self-help group and I didn’t belong. I was young, with full mobility and a high cognition level, and I was at a much different place in my life than other attendees. I was talking about dating, and they were talking about grandchildren. I left the meeting determined to create a support system for myself and other young people living with MS.

Three months later, I joined a fellow MS warrior to launch a self-help group for people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s—the Young Person’s Group. A decade later, YPG is thriving in Los Angeles and has expanded to include teens living with MS. It was my first step on a journey I continue today, and the first time I recognized myself as the inherent activist I am.

Alliance for Justice defines advocacy as any action that speaks in favor of, supports or defends, argues for a cause, or pleads on behalf of others. And I had no idea that with this step into advocacy, I had managed to incorporate all three types—self, individual, and system. Self, meaning I needed the self-help group to be effective for me. Individual, meaning I wanted to create a system of support for other young people. And system, meaning I was creating a new opportunity to support members of the MS community. Self-advocacy is tricky because it’s often easier to fight for someone else’s needs rather than fighting for your own. Until it’s necessary.

In 2019, I was diagnosed with superior semicircular canal dehiscence, which went undiagnosed and misdiagnosed for almost a decade. MS and SSCD share symptoms, such as fatigue, migraines, and vertigo. However, the one symptom I was experiencing, which could only be connected back to SSCD, was autophony, or hearing my organs moving internally. It was debilitating me and I couldn’t find a provider who believed me. Years into this process, I successfully diagnosed myself. It didn’t matter, so I continued begging providers to help me.

Looking back, I see that as a white, cisgender woman with bachelor’s and master’s degrees, who speaks English as a first language, and who has experience working in healthcare and insurance settings, I am the most wellpositioned to get the care I need. But it took me almost a decade to get relief. And that means people from marginalized and under-resourced communities, which are disproportionately communities of color, will never have the same opportunity I had for their own relief. I am dedicated to changing that narrative.

In 2020, I launched my small business, Eye Level Communications, providing strategic services that help businesses implement disability inclusion with confidence. Recently, I helped transition the women’s wheelchair basketball team I’ve played on for seven years to a new, sustainable, nonprofit model.

For me, advocacy is a way of life. It’s the work we do to ensure access and inclusion for ourselves and all members of the disability community. It’s our dedication to creating and holding space for conversations—at eye level—that connect people to one another, their communities, and themselves.

Sarah Kirwan (back row, right) and the wheelchair basketball team she helps lead.

Sarah Kirwan lives in California. She wrote about her SSCD diagnosis in the Winter 2022 issue, at hhf.org/magazine. For more, see eyelevel.works.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.