9 minute read

Anthroposophical Views Dora Wagner

…and then skipping over puddles again

Dora Wagner

Advertisement

The very nature of the nose is to love fragrances

Lü Bu We; 300 - 235 BC

Dazzling, heady, purifying, empowering, touching and gently earthy, that's how I would describe the pleasing fragrance that often accompanies a summer rain. When, after a long period of warm, dry weather, the first raindrops touch the ground, the air immediately gives off this unique, unmistakable perfume of the Earth. ’Petrichor’, created by rain falling on parched soil, is a neologism, invented by mineralogists in the 1960s, when investigating the smell of rain (Baer et al., 1964). The word is made up of two Greek parts, πέτρα (petra) for stone and ἰχώρ (ichor), which roughly stands for 'blood of the gods'. So, the compound means 'blood of the gods from the stones'. With this, the mineralogists wanted to express that this typical summer smell can arise wherever rain meets earth— not only on grass, but also on the city’s asphalt. At the very first contact between your nose and this scent, an unbelievable variety of impressions emerge— including memories of jumping with all your might into puddles and having a lot of fun. Because the human sense of smell can distinguish more than a trillion different scents (Keller et al, 2014)— far more than our eyes and ears combined —it is mainly our nose that evokes these Proustian moments, these sensory experiences that trigger a rush of memories, seemingly forgotten, taking us back to childhood days. Olfactory perception is the oldest human sense, the only one that is fully developed in the womb, and the first one we use after our birth. Newly born human babies cannot see well, so they follow their nose, diving to their mother's breast by simply smelling the milk and trying to find the source of the scent. In childhood we tend to determine which scents we will like or hate for the rest of our lives.

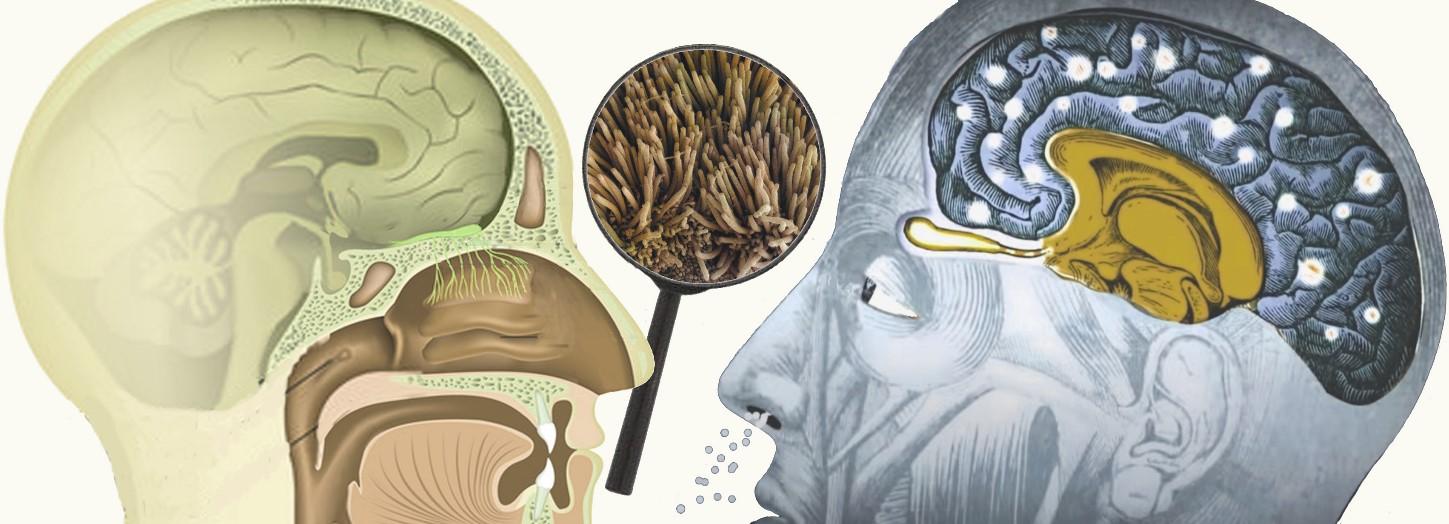

The first stage of olfactory detection is two mucous membranes in our upper nasal area, each roughly the size of a £1 coin, about 4 cm². Between two and five million olfactory receptors are located on the hairs in our nose, which protrude into the watery, proteinaceous layer of our nasal mucosa. Each of these olfactory cells, which are renewed every four to six weeks, specialises in a particular scent component. The odour that we suck in through our nostrils triggers biochemical reactions in these cells. All this information is processed by the olfactory bulb, amplifying the cells’ reactions 100-fold and generating electrical impulses that are transmitted directly to the front of the brain for further processing. Smells take a very fast and direct path to our limbic system, via the amygdala and the hippocampus— the regions of the brain involved with emotion and memory. That’s why fragrances have a much deeper impact on our

experience than we imagine, and we will even blindly recall places, people, and situations if we perceive corresponding smells. Since the olfactory sense is the one that is most developed in a child up to the age of about ten, when vision takes dominance, and since scent and emotion are stored as shared memories, it is olfaction that most evokes our childhood memories, whether conscious or unconscious, and it is scent that can guide us back to a sense of well-being. Several studies have now verified the existence of olfactory receptors in different human tissues, exploring their involvement in various physiological and pathophysiological processes. For example, research indicates that our hearts can also detect scents, and that it might be possible to heal diseases with appropriately scented ointments (Jovancevic, 2017). Just as toxic and bad-smelling vapours can make us sick, a fragrant preparation may have a healing effect on corresponding organs.

To have a ‘good nose’ remains essential for us throughout our lives, especially when it comes to choosing food. Compared to our sense of smell, our sense of taste is underdeveloped, yet smell and taste are closely connected. Without our noses, we would not be able to identify our beloved dishes. Basic sensations— salty, bitter, sweet, and sour —can easily be identified by the taste buds on our tongue. For more complex flavours, such as raspberry ice cream, both senses are required. As we chew, the aroma of the food reaches our nasal mucosa via a connection between the oral and nasal cavities. So, there is nothing worse than a stuffy nose because this means we can neither taste nor smell. In fact, our entire well-being is affected, even our sleep, speech, and hearing. Our noses mean no harm; as in all allergic and non-allergic forms of rhinitis, the hyperreactivity of our nasal mucosa helps protect us from invaders (Bachert, 1996).

The respiratory part of the nasal mucosa is located in the area of the lower and middle turbinate; it serves to clean, humidify and warm the air we breathe. Over a distance of about seven centimetres between our nostril and the rear opening of the nose to the pharynx, air is either heated or cooled to 34.5 °C. In order to maintain this temperature, whatever the external weather, our nose has a sophisticated system. The most important component of the mucous membrane’s surface, several hundred square centimetres in size, is a kind of carpet consisting of millions of fine cilia, each up to 0.01 millimetres long. Moving together in waves, their surfaces, which are partly watery, humidify the inhaled air when it is hot. At the same time, the fine blood vessels under the mucous membrane surface warm the air when it is cold. The wave-like movements of the cilia also transport inhaled pollutants, such as dust particles, towards the oral cavity, where they are then swallowed (Vaupel, 2015). (You may be alarmed to learn that the mucous glands of the ciliated epithelium produce around two litres of secretion every day). For emergencies, there is a second olfactory system. One of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve runs through our entire nasal mucosa. The trigeminal-nasal system recognises only coarse olfactory stimuli in very high concentrations— smoke, menthol, ammonia, or acids —but still protects us from ingesting toxic or unhealthy things.

As a little girl, I wanted to protect myself from Onions and Horseradish, whose strange, pungent smells brought tears to my eyes. I also disliked our home remedies, which included applying Onions to my ears for aches and pains, or topically as first aid for insect bites, and serving a Horseradish or Black Radish sandwich for colds. How could I have known the health-giving powers of mustard oils? Today, of course, I’m very pleased that Horseradish has been crowned Medicinal Plant of the Year 2021 in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Cruciferous vegetables, such as Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), Cabbage (Brassica oleracea), Mustard (Brassica nigra), Wasabi (Eutrema japonicum), Rocket (Eruca vesicaria), Radish (Raphanus sativus) and Cress (Lepidium sativum) contain, among other substances, pungent essential oils that are responsible for their sharp taste. In Mustard seeds, which are scentless when dry, the

characteristic pungent, burning flavour only develops when water is added. Only then are the important pharmacologically active essential mustard oils (isothiocyanates; ITCs) released. Plants produce ITCS for their own protection, and they have been used successfully for decades in the treatment of acute and frequently recurring respiratory infections. The same substances are present in Horseradish in an inactive, stable form— as mustard glycosides, ‘glucosinolates’ —again being broken down into their compounds with the help of enzymes and water. In water, the antimicrobially active ITCs emerge from the inactive form with the help of the enzyme ‘myrosinase’, which is contained in Horseradish root. ITCs act according to the multi-target principle, affecting different points in a disease process. They fight both bacteria and viruses, and have anti-inflammatory and anti-adhesive effects. During the breakdown of mustard oil glycosides by hydrolysis, heat is released (Kriegel et al., 2014). Accordingly, after a good meal, it gets hot in our intestinal tract. Anthroposophical medicine considers this phenomenon to provide the human body with warmth during colds. So, for example, foot baths with powdered Black Mustard seeds, and compresses with grated Horseradish root are used to relieve rhinitis and sinusitis. Also, by means of these external applications, patients can benefit from the anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antibacterial properties of mustard oils.

A somewhat special, but very helpful, remedy for inflammations of the nose is a compress of Horseradish (Sommer, 2013). It is important the eyes are covered, and that the application does not to last longer than a few minutes. First, a paper handkerchief or similarly sized cotton cloth is cut in half, to make two packets. These are then each filled with half a teaspoon of freshly grated or preserved (not sulphurated, without cream) Horseradish. The compresses are placed on the affected areas— for example on the cheek bones to the left and the right of the nose, or on the forehead —so that the side with only one layer of paper lies on the skin. Be careful to keep your eyes closed and do not rub them with Horseradish-contaminated fingers. As a precaution, it can be helpful to cover them with moist cotton pads, swimming goggles, or similar. The first application of the Horseradish compress should not last longer than one minute, and four minutes at the most — otherwise damage to the nerve corpuscles in the skin can occur. As soon as the skin reddens, the compress must be removed. Afterwards, the treated area must be provided with a nourishing skin oil, such as Olive or Almond. The compress can only be applied again when the reddening of the skin has completely disappeared, and only up to two times a day. Similarly recommended therapies with Mustard powder are footbaths or neck-compresses.

It’s not only in illness, but in age that we tend to lose our sense of scent, and so our wellbeing. But just like a muscle, our nose can be strengthened by exercising it every day, by simply making a constant effort to be mindful and aware of what we smell. The more we use it, the stronger our olfactory ability becomes. So, we really should follow our nose— sniff your way through life, relax more often on a fragrance journey, coddle yourself with scents that evoke beautiful memories. Each of us knows a lot of smells. Each of them can initiate cascades of reactions in our brains and, simply, make us feel happy.

Images: Collages and drawings by Dora Wagner.

References Bachert, C. (1996) ‘Die chronisch verstopfte Nase – Zur Klassifikation der nasalen Hyperreaktivität’, in Deutsches Ärzteblatt; 93 (Heft 16): A-1034–1038 Bear, I J. & Thomas, R. G. (1964) ‘Nature of Argillaceous Odour’; in: NATURE, Vol. 201:993–995 Jovancevic, N. et al. (2017) ‘Medium-chain fatty acids modulate myocardial function via a cardiac odorant receptor’, in Basic Research in Cardiology, 112 (13) Keller, A. et al. (2014) ‘Humans Can Discriminate More than 1 Trillion Olfactory Stimuli’, in Science 343 (6177):1370-1372 Kriegel T. & Schellenberger W. (2014) ‘Bioenergetik’, in Heinrich P et al. Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer: Berlin Lü Bu We (239 BC) Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We (Lüshi chunqiu), 239 v. Chr.; übersetzt von Richard Wilhelm 1928. Erster Teil. Buch V Dschung Hia Gi. 4. Kapitel Sommer. M. (2013) Heilpflanzen, Verlag Freies Geistesleben & Urachhaus: Stuttgart Vaupel, P. et al. (2015) ‘Anatomie, Physiologie, Pathophysiologie des Menschen’, in Wissenschaftliche, Verlagsgesellschaft: Stuttgart