6 minute read

Foraging Through Folklore Ella Leith

The slow traveller’s joy

Ella Leith

Advertisement

Always happy to celebrate slowness, for this column I set off down a familiar path. The wrong path, as it turns out.

To me, the byname ‘Old Man’s Beard’ refers to Wild Clematis (Clematis vitalba), a climber native to the UK that sprawls all over hedgerows in vast tangled clusters. In the winter, its fluffy white seed-heads give it the name I know it by, as well as the less common name of ‘Father Christmas’. In the summer, its fragrant white flowers are as abundant now as when John Gerard described them in his 1597 Herball, coining another of Wild Clematis’s names:

decking and adorning waies and hedges, where people travel; and there upon I have named it the Traveller’s Joy. These plants have no use in physic as yet found, but are esteemed only for pleasure, by reason of the goodly shadow which they make with their thicke bushing and clyming, as also for the beauty of the floures, and the pleasant sent or savour of the same. (quoted in Mabey 1974, 68; spellings as written.) As Traveller’s Joy and as Old Man’s Beard, Wild Clematis has become one of the ‘botanical mascots of footweary wayfarers’ (ibid, 67). An appropriate plant, I thought, to explore for The Slow Issue.

And so I meandered, researching Wild Clematis. I learnt more of its bynames: ‘Shepherd’s Delight’, ‘Poor Man’s Friend’. Perhaps these names allude to the same aesthetic and practical attributes described by Gerard: its flowers giving delight to passing shepherds, and its bushy tangles providing welcome shelter from sun or rain for those working outdoors. There is even the claim that beggars used to rub juices from the leaves into scratches on their skin, ‘raising large superficial sores and giving the user an appearance miserable enough to con alms out of the most hard-hearted wayfarer’ (Mabey 1974, 68). But more likely these names go hand in hand with its other monikers: ‘Boy’s Bacca’, ‘Baccy Plant’ and ‘Smokewood’. In winter, its dry stems would be cut and smoked as a foraged substitute for tobacco— the original wild Woodbine (‘Woodbine’ being a generic name for a creeper). Wild Clematis was also once known as ‘Bed-wind’, presumably alluding to how strongly it winds itself around the supporting hedge or tree; I wondered whether there could be a connection here to old rope beds, since the stems of Wild Clematis have been used in the past to make a rough rope. Winding derives etymologically from the same root as wander… I was enjoying my wandering with Old Man’s Beard.

Then I told my mother what I was writing about. “Old Man’s Beard is a lichen, isn’t it?” And so it is. I should be focussing in this Slow Issue on Usnea spp, not Clematis vitalba. I had set off on the wrong path. Oh well. It was a fruitful detour. The words of Edith Sitwell’s poem come to mind: and nothing is lost, and all in the end is harvest.

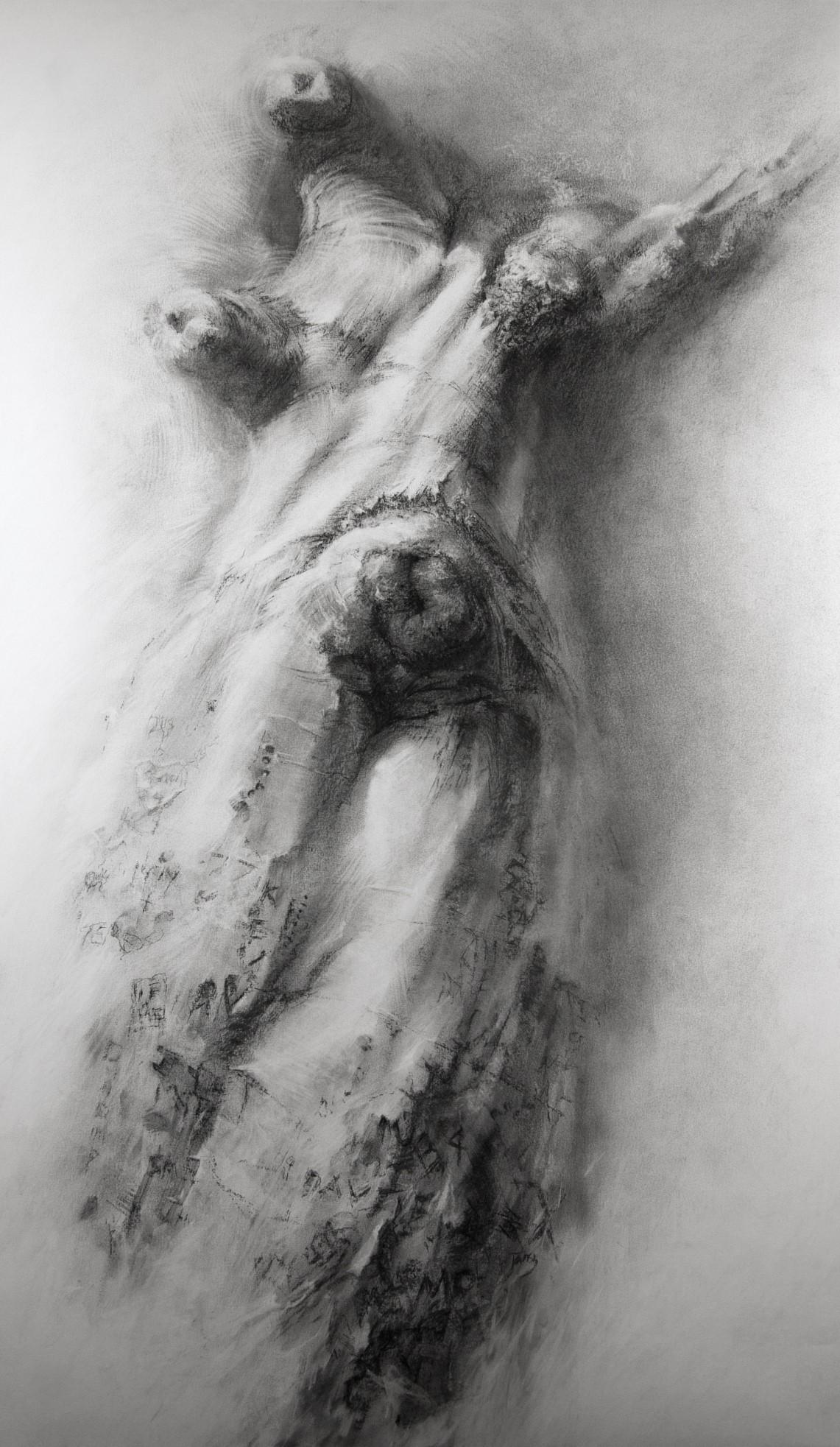

Usnea’s ‘Old Man’s Beard’ has a different quality to that of Wild Clematis. Whereas Wild Clematis’s seed-heads are light and downy and scatter in the wind ‘like insects on the wing’ (White 1788, quoted in Mabey 1996, 45), Usnea‘s silvery fibres are scratchy and tangled. It is itself very old. Extremely slow growing, a well-developed lichen is likely to have been tenaciously clinging to an old tree or fence post for over a century— but only where the air is pure enough to sustain it. It demands a slow pace of air travel: the ACE/Sunday Times Air Pollution Survey of 1972 observes that ‘the slipstream of cars tends to blast [lichens] off the nearside of trees. In one place they were wiped off above a fence but not below it’ (quoted by Mabey 1974, 136).

So, I set off on a new path with this other Old Man’s Beard, catching little glimpses of the old path as I went. Grass Roots Remedies claim

that Usnea may have been the first tinsel used on Christmas trees; I remembered that Wild Clematis is also called ‘Father Christmas’. Lichens need clear air and can be used to treat respiratory conditions; smoking woodbines might have caused or exacerbated these conditions. Usnea can also treat skin afflictions— perhaps even those self-inflicted using the juice of Clematis vitalba. Further along, I started catching glimpses of paths I’ve previously trodden for Herbology News. Lichens, Mabey says, are ‘a special case. They are not one plant but two, a simple foodproducing alga and a fungus shell living in partnership’ (1974, 136). Like the fungi explored in The Connective Issue, lichens are plant-like without being strictly plants; although they are typically classified by their fungal component, they straddle different biological Kingdoms. Like the seaweeds discussed in The Energy Issue, lichens are partly algal; Grass Roots Remedies lists ‘Mountain Seaweed’ as an alternative Hawai’ian name for Old Man’s Beard. I had explored the association of seaweed and drowning in Gaelic folklore; strangely, this is also echoed in relation to lichens.

Lichens have traditionally been used as clothes dye, particularly for the oranges and yellows derived from Crottle or Crotal (Parmelia saxatilis). In the Hebrides, a longstanding superstition told that wearing Crottle-dyed clothes on a boat would bring about death by drowning. One typical local legend was recorded in 1970 from Angus Fletcher of Snizort, Skye. A Uig man called Lachlann planned to emigrate to Australia in the late 19th Century but had a change of heart when the ship stopped in Lochmaddy, North Uist. While waiting for a lift back from some Uig fishermen, Lachlann collected Crottle from the rocks and, lacking a bag, stuffed it into his trousers. On the voyage back over the Little Minch, a storm arose from nowhere and the fishermen asked if anyone was wearing Crottle-dyed stockings; Lachlann immediately threw his stash overboard, trousers and all. There are many other taboos associated with fishing (including avoiding ministers, red-haired women, lefthanded men and various animals, as outlined by James MacArthur of Portnahaven, Islay, in 1969), but the link between land-based algae and water-based death is evocative. Another name for Old Man’s Beard is ‘Woman’s Long Hair’, and the imagery of hair and seaweed also go hand in hand.

This column doesn’t arrive anywhere. Maybe that doesn’t matter. I’ve wandered along different paths and the slow journey was worth it. To paraphrase Mabey, Old Man’s Beard is a special case. It offers us not one path but two, sometimes running parallel, sometimes intertwining, but always taking the time it needs.

References Abdel-Fatteh, A. (2020) ‘Lichens in Folklore: Medicines and Dyes’, Microbial Biosystems 5(1), pp. 50-51. Easy Wildflowers. www.easywildflowers.wordpress.com/about/cr eam-wildflowers-of-the-uk/clematis-vitalbathe-wild-clematis/ Grass Roots Remedies. www.grassrootsremedies.co.uk/2017/01/20/h erb-profile-old-mans-beard-lichen Mabey, R. (1974) The Roadside Wildlife Book. David and Charles, Newton Abbot and London. Mabey, R. (1996) Flora Britannica. SinclairStevenson, London. Sitwell, E. (1957) ‘Eurydice’, Collected Poems, Macmillan, London.

The Gaelic interviews mentioned can be found on the Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches website, the online portal for selected items held in the School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive at the University of Edinburgh. Angus Fletcher: http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/93 365 James MacArthur: http://tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/11 78