Underground Valletta

Late Neolithic

Construction of complex megalithic structures and communal burial places, and crafting of fine objets d’art.

Late Bronze Age

Flourishing of fortified settlements.

Early Neolithic First evidence of cultivation in the Maltese Islands.

Early Bronze Age

Fresh wave of colonisation and arrival of new technologies, repurposing of megalithic temples.

eventual into dependency.

3800 BC 5900 BC 1500 BC 2000 BC 800 Phoenician Carthaginian Foundation colony anAnnexation

Rome

Thriving of economic and artistic pursuits, and endowment of towns of Melite and Gaulos with fine properties.

1530

settlements.

Foundation of Phoenician colony and trade hub with eventual metamorphosis into a Carthaginian dependency.

Succession of diverse dominations and abandonment of coastal settlements due to intensification of hostile incursions.

Transformation into a regional maritime hub and world-class stronghold with an exponential increase of population count.

1964

Achievement of Independence, establishment of Republic, termination of foreign military presence and accession to the European Union.

218 BC to 800 BC Phoenician and Carthaginian dominance Early Modern Period 535 AD Middle Ages Sovereign State

Stalactites hang undisturbed as silent witnesses to the years that these rock shelters have remained abandoned. They have built up in areas where there is water constantly dripping from the ceiling. When exposed to the air, the dripping water leaves a deposit of calcium carbonate from the rock, which in time builds up into a stalactite.

These colourful and geometrically patterned cement tiles offer some colour in the otherwise drab cave-like cubicles. Probably, scavenged from the ruins of bombed houses, they had the practical function of being easier to keep clean than bare stone. These tiles were especially popular in Maltese houses in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

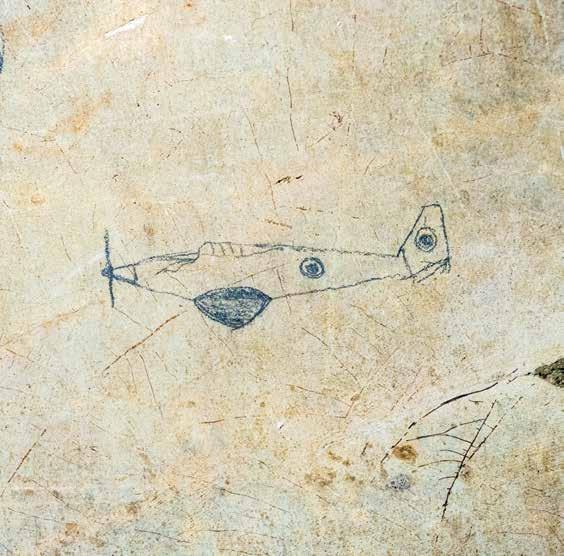

Military aircraft are a popular motif among the pencil drawings on the walls of the cisterns. The graffiti resemble the Hurricane or Spitfire. Dramatic aerial battles raged over Malta between the Axis and Allied planes. Some people were so mesmerised by the spectacle of dogfights in the skies that they would rush to a good vantage point rather than seek shelter during air raids.

High humidity and water infiltration meant that any item left on the floor would get wet. The stone walls of the cubicles still hold rusted nails and brackets that held shelving and bunk beds put up by their occupants in a desperate attempt to keep dry.

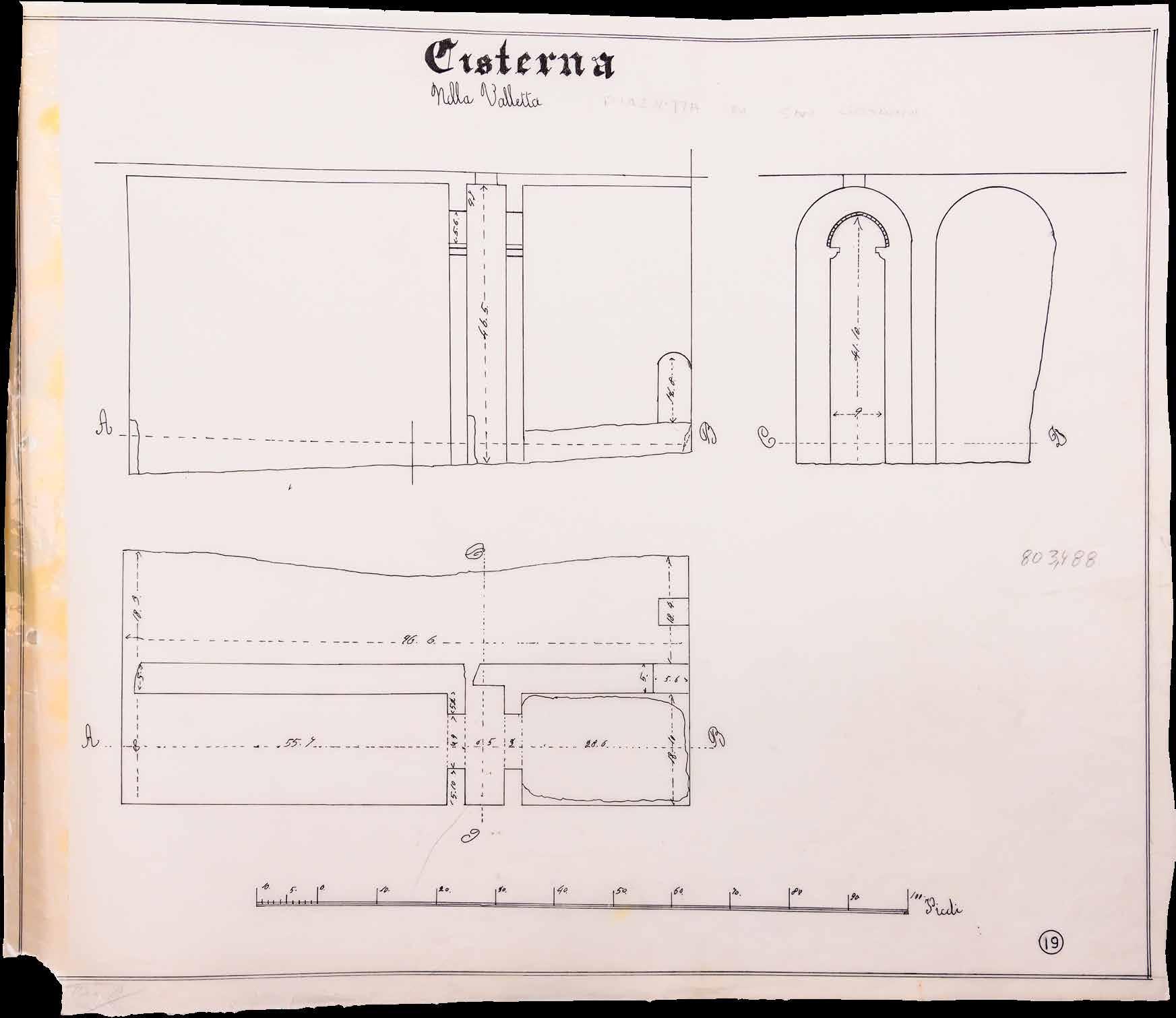

The sump pit lies directly below the opening into the reservoir through which water could be drawn to street level. The floor of the reservoir sloped towards the sump, collecting the last dregs of water if the reservoir was emptied during the dry months. The pit would be cleaned periodically of silt brought in with rainwater.

A symbol of the strong faith of the Maltese during World War II, religious niches adorned all public shelters. Devotion to Our Lady was especially strong, as Maltese women identified with her strength and endurance through their hardship. The Holy Rosary was recited daily by the occupants of the shelters, praying for deliverance.

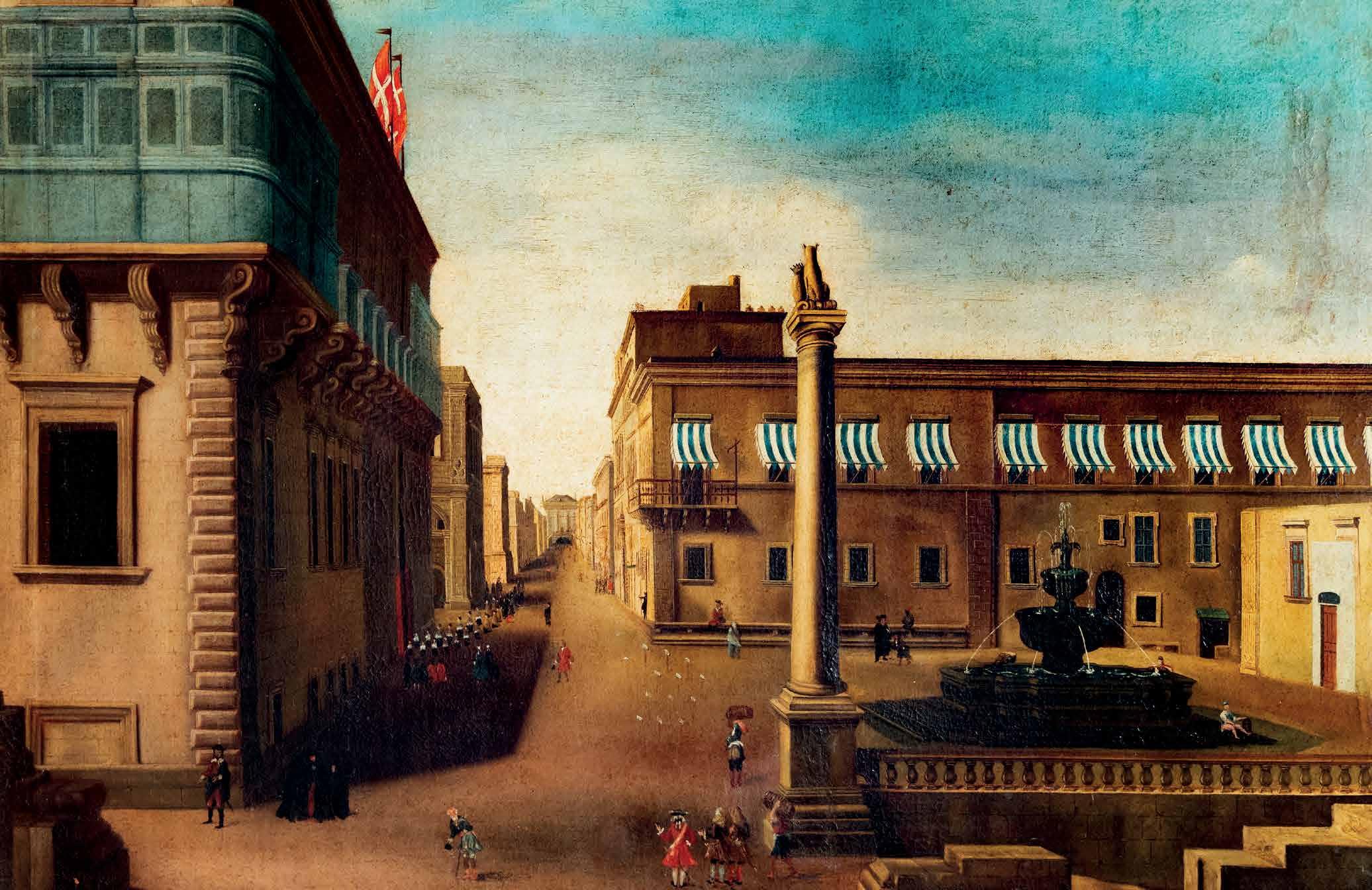

Entering Valletta through City Gate brings you onto the main street. Different administrations have given different names to this street. For the Knights of St John, it was ‘Strada San Giorgio’, ‘Rue Nationale’ for Napoleon, and ‘Strada Reale’ or ‘Kingsway’ during the British colonial period. Today, it is named Republic Street. Running along the spine of the Valletta peninsula, it has long been the heart of the Capital: the place to display status, conduct business, attract the attention of potential suitors as well as celebrate public and sacred occasions to the tune of a brass band.

Valletta follows a grid plan. Walk along Republic Street up to the crossing with St John Street. Before turning right towards the main entrance to St John’s Co-Cathedral, look left down St John’s Street to catch a glimpse of the steep descent to Marsamxett Harbour. At the next crossroad with Merchant Street, you will catch sight of the Grand Harbour. These junctions allow you to appreciate that you are standing on a narrow peninsula between two harbours.

While walking, you have passed over various gutters, drains and man-holes, the only hint of the vast and intriguing complex of tunnels that lie beneath Valletta’s streets. At the junction of St John Street with Merchant Street, you will arrive at the staircase hewn out of the rock that will take you down to Underground Valletta. You are about to leave the everyday bustle of the City, to descend into the dark silence of spaces, long abandoned as the needs of the City have moved on.

Underground Valletta presents a unique perspective of Valletta’s history from the ground up. We marvel at the bastion walls, palaces, churches and piazzas that adorn Valletta, this UNESCO World Heritage Site but it took meticulous planning to support a city that had aspirations to be as splendid as any other early modern city in Europe. The Underground Valletta complex includes several bell-shaped water cisterns and a colossal reservoir, dug in order to store fresh water for the City’s needs. Built on a peninsula that lacked natural springs, the Knights developed sophisticated systems of water management. The Underground Valletta tour includes a visit to one of the largest and finest reservoirs in Valletta which is the only one of these immense water tanks to be open to the public.

Connecting the cisterns and the reservoir is a complex of shelters dug during World War II. Following the path of the streets above them, these shelters offered effective protection to civilians from the barrage of bombs dropped by the Axis powers in their efforts to grind the Islands into surrender. These shelters allow the modern visitor a glimpse of the conditions their occupants had to live in, as much of the City above was reduced to piles of rubble.

This publication sets Underground Valletta within its geological, social and political context to provide a fresh lens through which to explore the City and the hidden world beneath it. The underground area included in the tour is a small but representative section of the labyrinth of tunnels and spaces beneath the City.

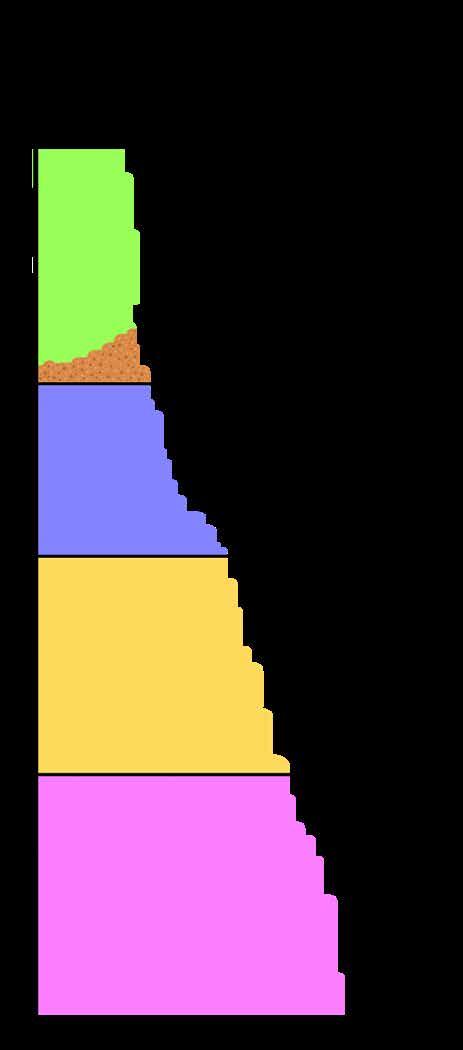

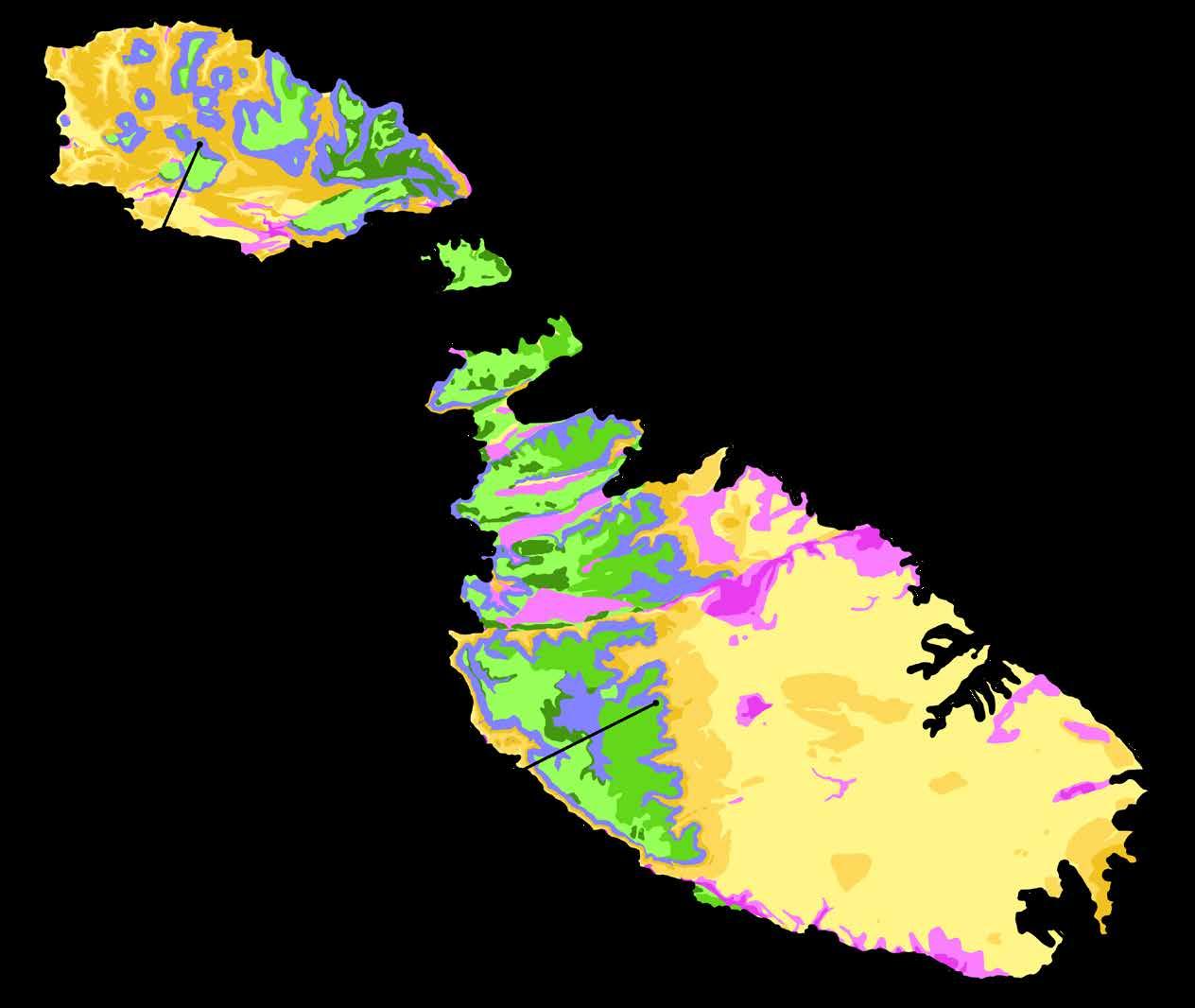

Malta is composed of sedimentary limestone. This essentially means that it is made up of different layers of rock that formed from sediments that built up on the seabed over millions of years. Each layer acquired different properties, depending on its depth, water movement and accumulated sediment which was partly composed of marine creatures that had died and decomposed. The main five layers, starting from the oldest, are Lower Coralline Limestone, Globigerina Limestone, Blue Clay, Greensand and Upper Coralline Limestone.

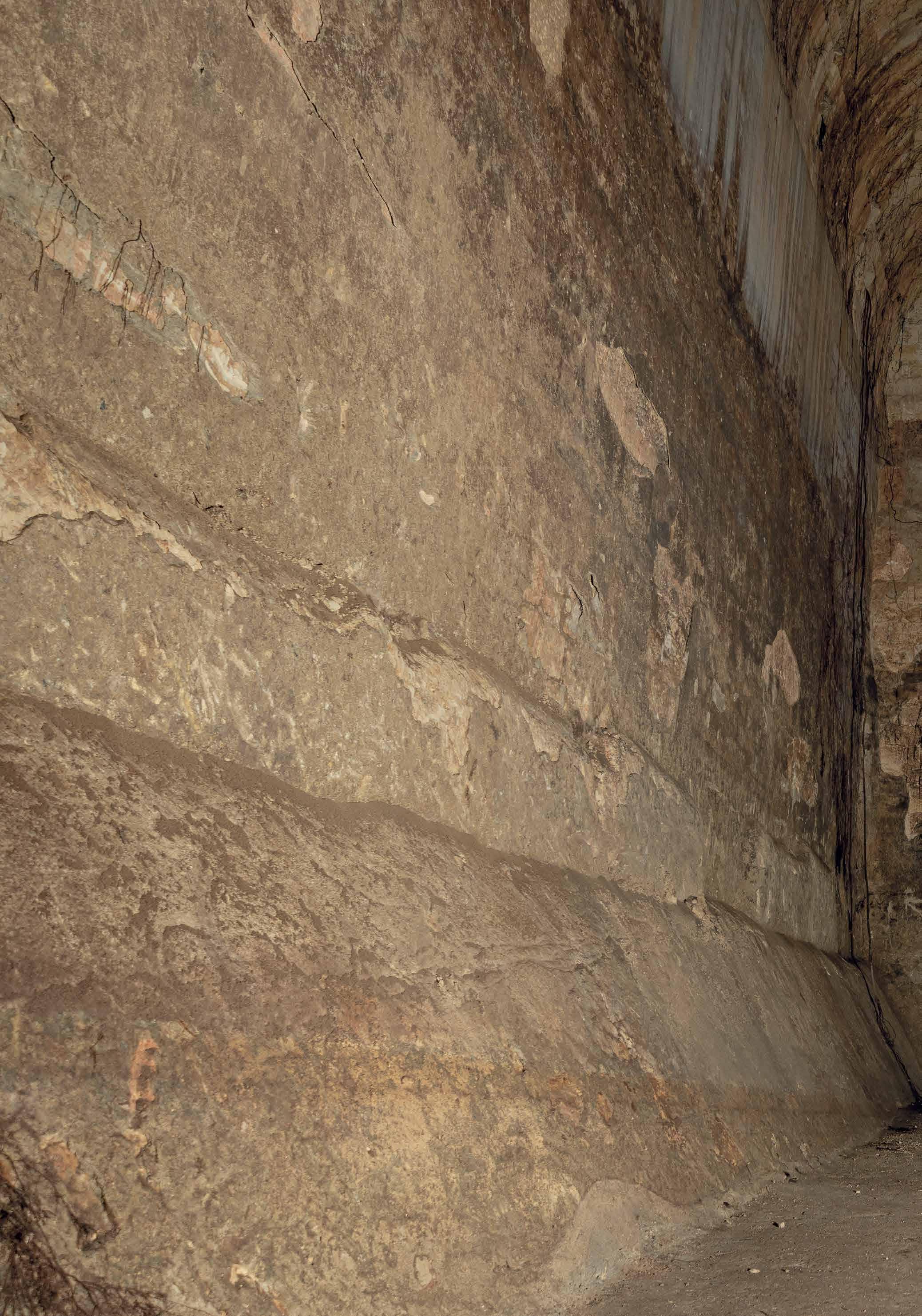

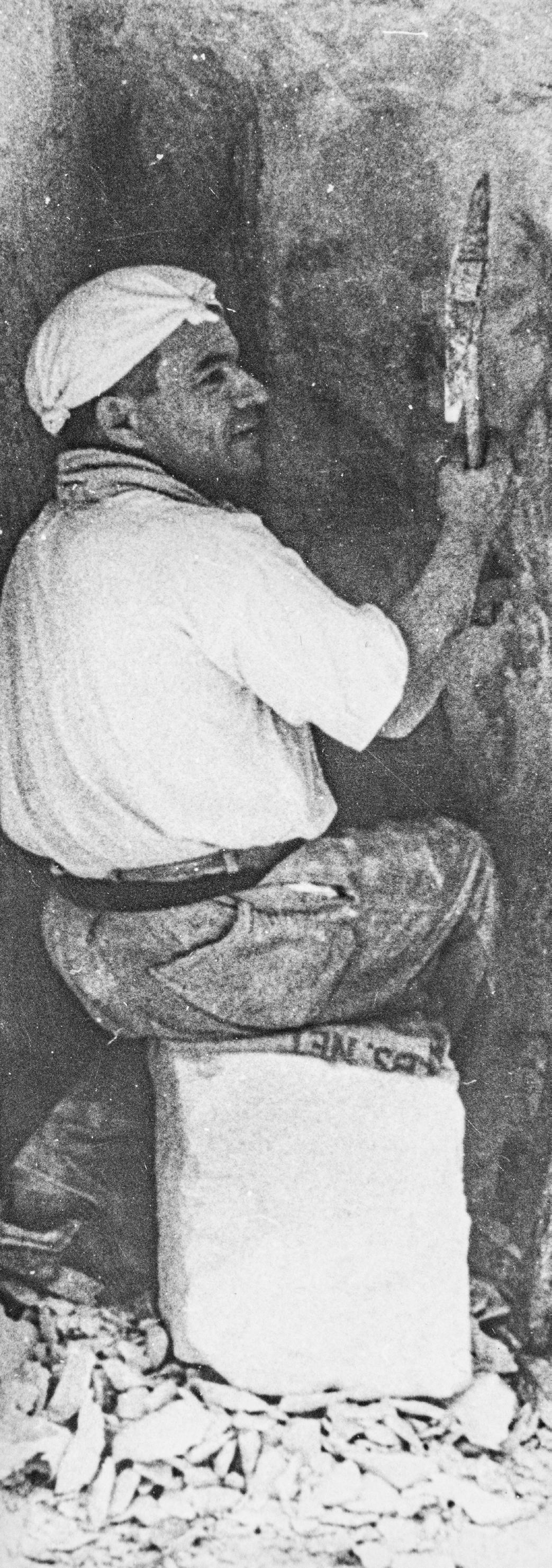

Valletta is built upon an outcrop of Globigerina Limestone, flanked by two harbours, Marsamxett Harbour and the Grand Harbour. Globigerina Limestone is a relatively smooth and soft stone that hardens when exposed to air. This has made it ideal for quarrying and building by Malta’s inhabitants since prehistory. The city of Valletta has been largely hewn out of Globigerina Limestone. A look at Valletta’s bastion walls shows how they were partly cut out of the Globigerina Limestone ridge, and partly built. Many of Valletta’s palaces, houses, churches as well as parts of the bastions were built from Globigerina Limestone easily quarried in situ. These quarries were efficiently converted into basements, crypts, water cisterns and reservoirs.

The properties of the different rock layers that make up the Maltese Islands control the distribution and availability of water. Blue Clay is the only one of the layers impermeable to water and is found mainly in north and north-west Malta and on Gozo. – Blue Clay creates a barrier to water percolating through the more porous rock, forming a perched aquifier underground. Water spilling out of the edges of this aquifer formed freshwater springs. Humans have exploited these water sources since prehistory in order to irrigate local fields and provide water to humans and animals. They lent themselves to settlement and helped determine the location of the old cities of the Ċittadella in Gozo, and Mdina in Malta to exploit these ready sources of water.

In south-eastern Malta, which is mainly covered in the more permeable Globigerina Limestone and contains few natural springs, people historically had to rely on creating cisterns in order to capture and store rainwater to see them through the dry summer months. Valletta was built in this part of the Island, on Mount Sceberras, a peninsula between two harbours, which lacked any natural water springs when works began in 1565.

Above: Simplified map of Malta’s surface geology.

Opposite: Fort St Elmo bastions built into the bedrock.

Ċittadella

Mdina

Valletta

Upper Corraline Limestone Blue Clay

Hard

Soft

Hard Soft & hard layers

Globigerina Limestone

Above: Simplified map of Malta’s surface geology.

Opposite: Fort St Elmo bastions built into the bedrock.

Ċittadella

Mdina

Valletta

Upper Corraline Limestone Blue Clay

Hard

Soft

Hard Soft & hard layers

Globigerina Limestone

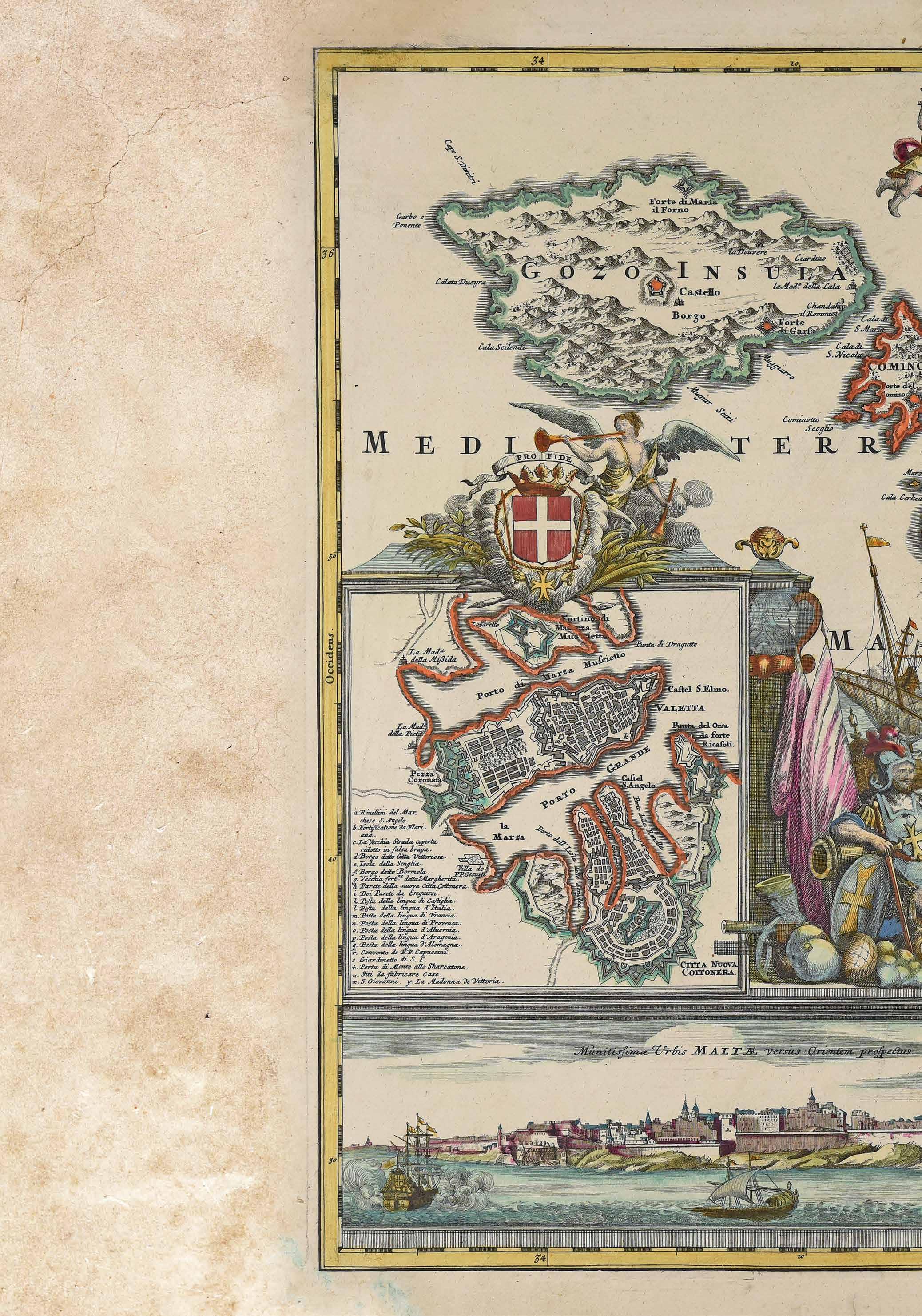

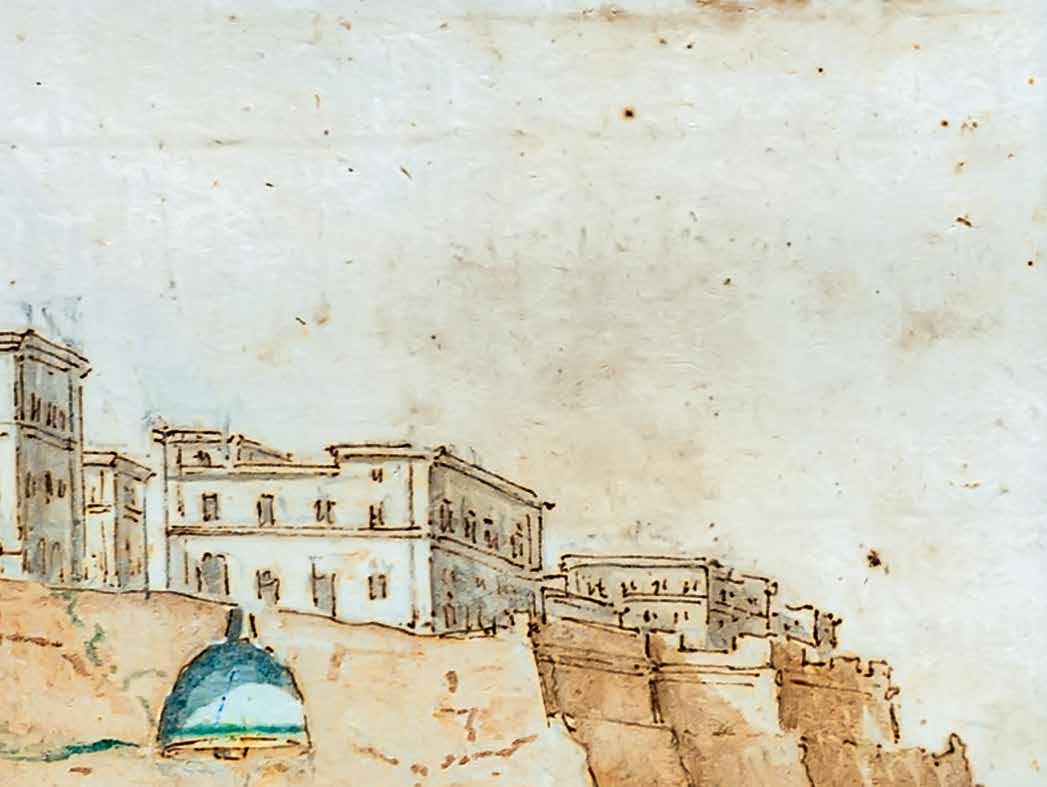

The natural harbours lured the Knights, who had arrived on the Islands in 1530, away from Mdina. A naval power, they initially set up their main seat of government in the fortified city of Birgu. After the Great Siege of 1565, they set about building a city from scratch upon Mount Sceberras.

The harbours and submerged valleys formed by rising sea levels over the past twenty thousand years, while the Three Cities, Valletta and Sliema are their plateaus. Mount Sceberras is the longest and highest ridge in this intricate system of harbours. Moving the seat of government to the Grand Harbour, set in motion changes in the pattern of settlement of the Island. A growing population in the relatively drier parts of the Island meant that Malta had to devise increasingly sophisticated systems to source fresh water and transfer it to the cities and towns.

Malta was invaded by a force of over 30,000 Ottoman troops in 1565. The lack of coordination among the invaders, and the courage and steadfastness of the Knights and the Maltese, led to victory for the defenders. The Siege made it clear to all that the best hope of defending the Grand Harbour from future sieges lay in building a new stronghold upon the highest ridge overlooking the harbour, namely Mount Sceberras. The Ottomans lifted the Siege on 8 September 1565. The heroic defence of Malta by the greatly outnumbered defenders gave new hope that Christian Europe could withstand the advance of the mighty Ottoman Empire. Even two hundred years later, Voltaire is reputed to have said that “Nothing is better known than the Siege of Malta”. Seizing the opportunity, Grand Master de Valette sent envoys to European rulers pleading for funding to build a new city on Mount Sceberras. Grateful Christian rulers responded with financial help and technical expertise. In December 1565, Pope Pius V deployed his personal architect, Francesco Laparelli, to design the new city. Laparelli’s assessment of the task ahead was:

“The position has no qualities at all except for usable stone, a healthy atmosphere, large and beautiful harbours and a hill higher than any others nearby. … However, the place lacks water, lime, sand, wood, picks and shovels, beams, fascines, labourers and all kinds of timber. Malta is just a bare rock… short of [food] but despite all these disadvantages it has never been in our interest to abandon ports as fine as these to the infidels – and nor is it now – for if we do: woe to the people who live on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea and those sailing on it!” (Vella Bonavita 2018)

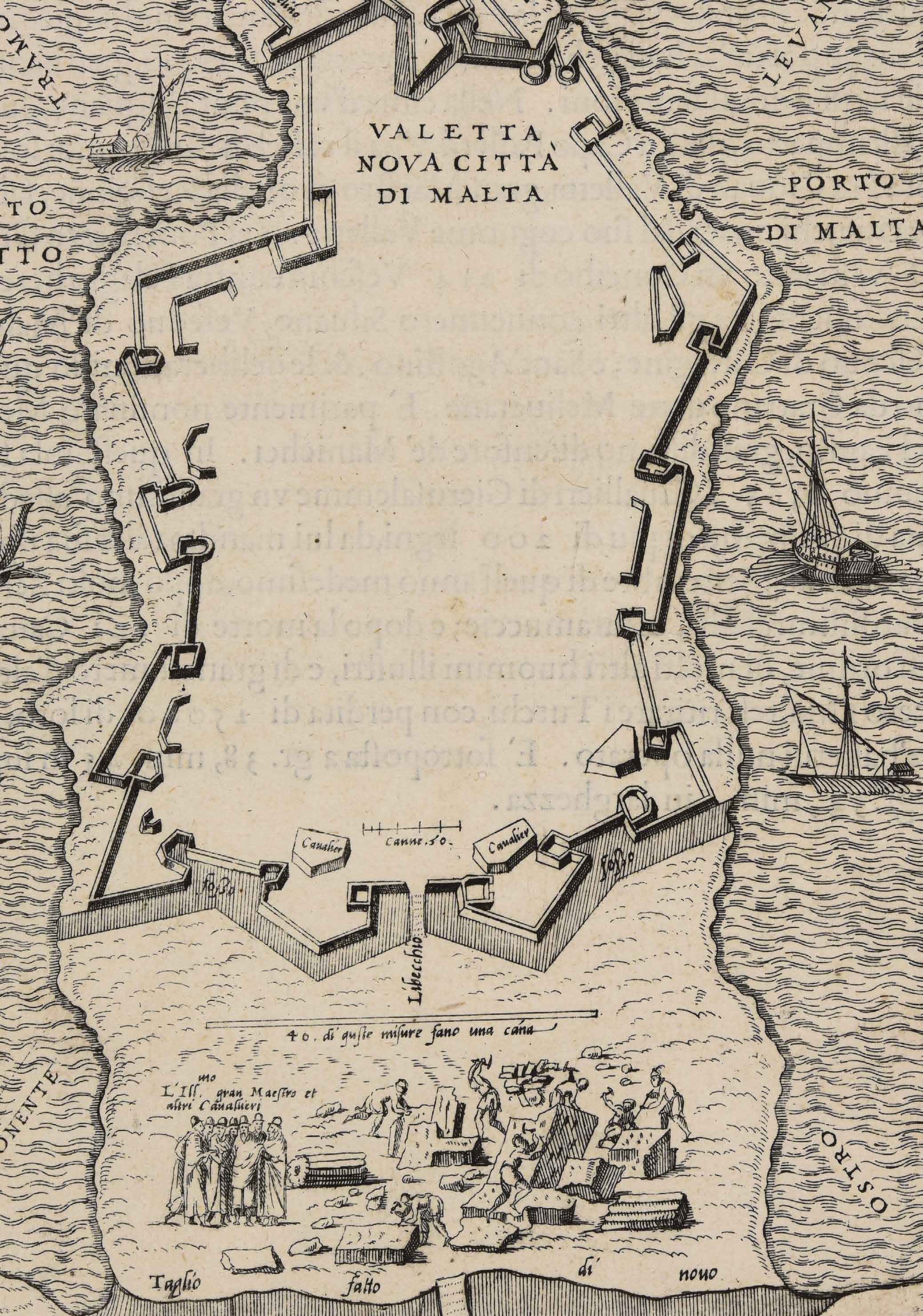

Valletta is a thick outcrop of Globigerina Limestone. The availability of this easily worked stone ensured that the building could progress relatively quickly and cheaply since the builders did not need to import this key material. It is estimated that a workforce of around 4,000 men was initially engaged in building the fortress city, consisting of stone masons, quarrymen, wall-builders, local and imported labourers and slaves. The rock forming the peninsula was sculpted to form impregnable defences. Fortification walls were built into them merging into a forbidding impenetrable wall above the shoreline. The stone that was being cut from the ditches and walls around the city was used to build its houses, monasteries and palaces. Valletta became a hive of building activity to meet the demand for stately homes, palaces, churches and public edifices. Other buildings needed to be erected included a slaves’ prison, stores, mills, shops, and true to their hospitalier origins, a magificent infirmary.

The main challenge, as noted by Laparelli, was the scarcity of natural water sources. A very small spring was discovered during excavations in the area where the Bishop’s Palace was later built, but nowhere near enough to meet the needs of the City. Besides drinking and washing, industries such as bakeries, blacksmiths and candle-makers, also required a regular supply of water. A further consideration was that if the Ottomans were to attempt another siege, Valletta would need enough water and grain to sustain the people within its walls for many months. Speed was of the essence, but so was meticulous planning.

Opposite: A view of Valletta being constructed. From the book De disegni delle più illustri città et fortezze del mondo di Giulio Ballino (1569), MUŻA.

Note the priority given to constructing the bastions first, and the depiction of the labourers cutting the stone.

Francesco Laparelli

Opposite: A view of Valletta being constructed. From the book De disegni delle più illustri città et fortezze del mondo di Giulio Ballino (1569), MUŻA.

Note the priority given to constructing the bastions first, and the depiction of the labourers cutting the stone.

Francesco Laparelli

Above: A section drawing of Valletta’s peninsula showing the wells dug into the bedrock. From Carapecchia’s 1723 water report, The National Library, Valletta. Courtesy: Daniel Cilia; Right: Inside a bell-shaped water cistern in Underground Valletta, similar to those drawn by Carapecchia.

Building a completely new fortified city was a thrilling prospect; it would be a testimony to the grandeur and significance of the Order. Tight building regulations were implemented, setting high standards for the quality of building and housing, as well as time frames to regulate the duration of building works. The Ufficio delle Case, a planning commission that had originally been set up in Birgu to regulate the building and letting of property, was updated for Valletta. The laws regulating water management stipulated:

- Every house shall contain an underground cistern for the collection of rainwater, as well as a place for the collecting of foul water, under penalty of 50 scudi for failure to comply;

- Stone for building purposes shall be obtained from the Manderaggio area. Stone recovered from the digging of the water cistern may also be used for this purpose.

The system was designed to maximise water capture during the rainy season, and its storage to see the City through the dry summer months or in the event of a siege. The regulations maximised efficiency. Builders excavated into the bedrock to create basements and water tanks, re-utilising the excavated rock for building.

The dozen or so steps to Underground Valletta lead to a circular chamber. Within this chamber, one can witness how the Knights exploited the peninsula’s most abundant resource - rock - to address its most serious challenge; the absence of any freshwater sources.

The chamber is in fact a water cistern. These kinds of cisterns are a typical feature on the Maltese Islands. They were an efficient way of using the rock to create a sealed chamber without the need of further construction. The opening through which the original hole had been dug would become the opening through which a bucket could be lowered in order to lift out water. The cisterns were rendered waterproof by a mortar over the porous Globigerina walls.

The cistern pictured was breached during World War II in order to create an access for the war shelters. One staircase leads up to street level, while another staircase leads into another cistern and down into the shelters.

Top: Access opening into a water cistern;

Top: Access opening into a water cistern;

Cities offer a particular challenge to city planners in managing waste, and Valletta was no exception. The Knights developed systems to keep foul water and drinking water separate. The 16th-century regulations of the Ufficio delle Case laid down the following:

“Provision shall be made in the foundations of the house for a connection to the public sewer into which shall flow all foul and waste-water, subject to a penalty of 50 scudi payable to the treasury of the Order for non-compliance.”

These early arrangements probably relied on rainwater run-off to flush waste water from the streets into the harbour. Houses were also required to have a cesspit (cisterna brutta) for solid waste. Cesspits needed to be emptied periodically.

This system appears to have been plagued by problems, compounded by a growing population that by the mid-18th century had reached 17,888 residents. The porous rock meant that cesspits and conduits often leached their contents into the rock, making their way to the harbours, as well as risking contamination of underground water tanks. The waterproofing of the water tanks had to be maintained, not just to prevent water from seeping out, but also as an extra precaution against impurities seeping in. Quicklime was also added to water tanks to correct impurities, while live eels were bred in water tanks to devour living organisms.

The reservoir that lies beneath the Great Siege Square was one of the largest in the capital. The whole reservoir is approximately 29 metres long, 11 metres wide and 14 metres high, above the sump pit. It held approximately 3.6million litres. Reservoirs are sometimes described as underground ‘cathedrals’ because of their immense height and elaborate roofing systems. Rather appropriately, the stone quarried for this reservoir was reputedly used for building St John’s Co-Cathedral.

The reservoir is made up of two interconnecting chambers dug out of solid rock. The chambers were roofed over with stonemasonry barrel vaults. Where the two vaults meet, a masonry wall was built to further strengthen these huge vaults. Large holes on either side of the ceiling were made to support the falsework (temporary structures like scaffolding) during the building of the vaults. The reservoir was rendered waterproof by applying a mortar lining to its walls.

The outermost chamber is considered the more elegant because of the reinforcing arches at the centre of the vault. Pleasing to the eye, these arches in fact have the functional purpose of reinforcing the ceiling where the vault is breached to permit the opening into the reservoir. A sump pit that lies directly beneath this opening used to allow the last of the water to be drawn from here when it had almost emptied. It also served to gather silt for easier cleaning. Through the opening above the sump pit, it was possible to extract water and to lower a person to carry out periodic cleaning of the reservoir.

Above: Holes that supported the falsework during construction of the vault still visible;

Left: A passage between the two chambers of the reservoirs allowing water to flow into the sump.

Above: Holes that supported the falsework during construction of the vault still visible;

Left: A passage between the two chambers of the reservoirs allowing water to flow into the sump.

Within a few decades, Valletta had become a thriving commercial city and corsairs hub. In 1590, Malta had a population of 30,000, a third of which lived in the harbour cities of Valletta, Birgu, Isla and Bormla. Economic activity drew in people from the countryside and from abroad. Despite the measures to capture and store rainwater, there was a chronic water shortage. When water supplies fell especially low, water would need to be brought in from elsewhere, sometimes even by boat from Marsa.

It was recognised that the solution to Valletta’s water problems lay in directing water from elsewhere. The Knights turned to the freshwater springs around the highlands of Rabat and Dingli. The immense costs proved an insurmountable obstacle until the Grand Master himself, Alof de Wignacourt, pledged to cover them. After several aborted attempts at constructing the aqueducts, de Wignacourt entrusted the task to the Bolognese hydraulic engineer Bontadino Bontadini. He mastered the changes in ground level through the creation of a series of underground galleries and above ground aqueducts to divert water from Rabat to Valletta. Bontadini overcame the porosity of Maltese stone by lining it with a special mortar of pozzolano, imported from Pozzuoli, near Naples. Valletta’s reservoirs could now be filled to capacity all year round.

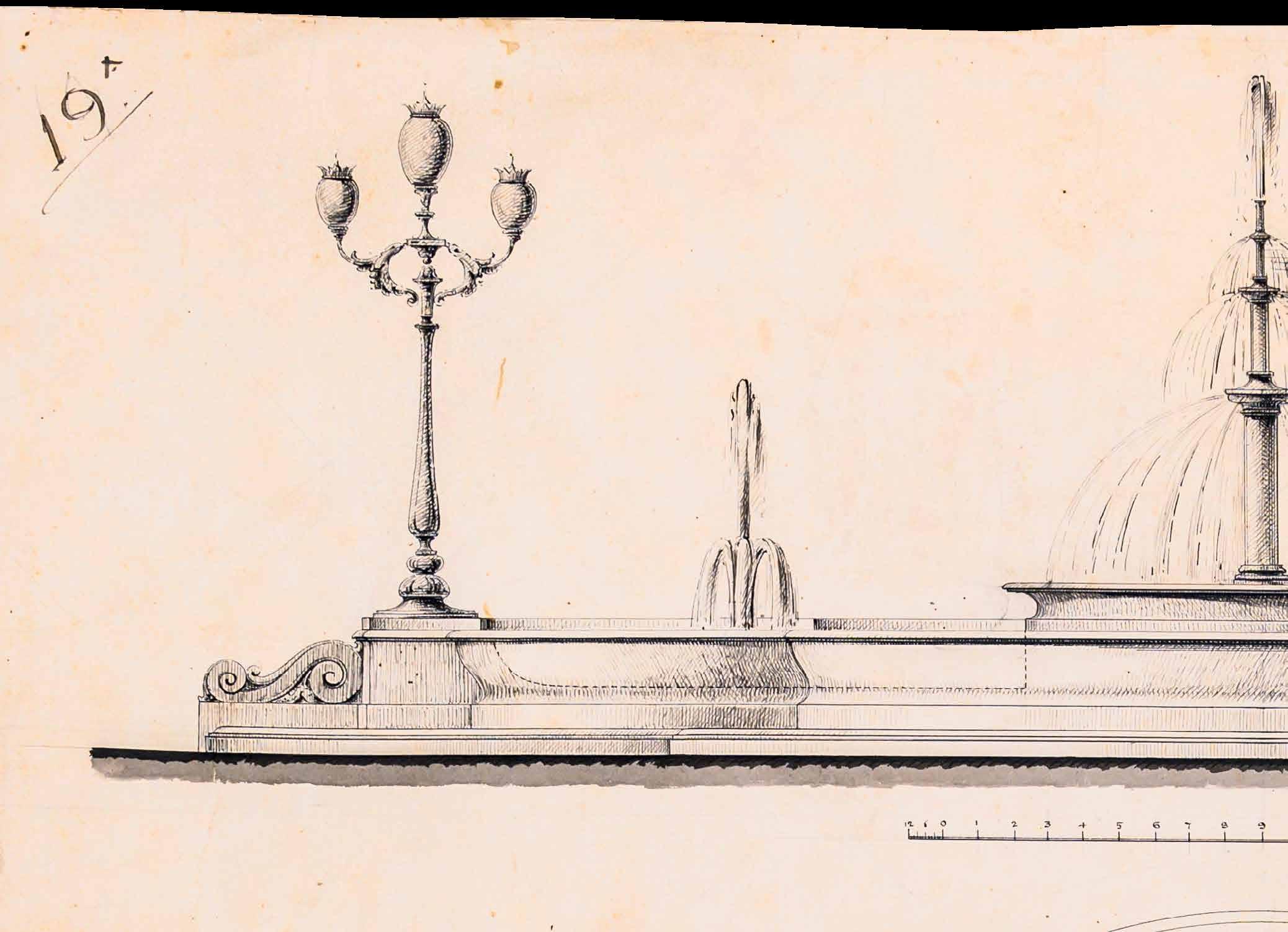

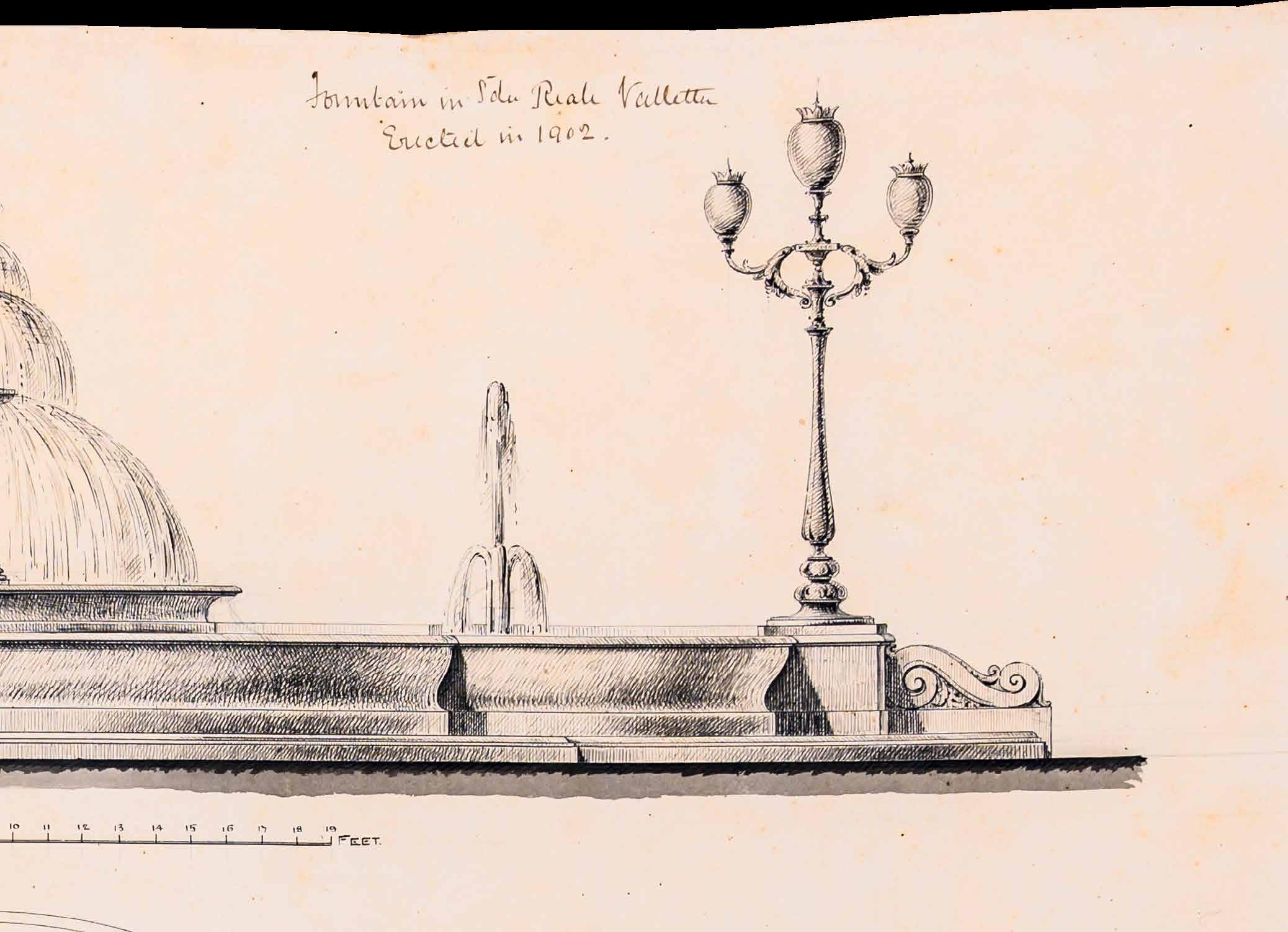

It is difficult to overstate the impact of this engineering marvel upon Valletta. It created the foundation for Valletta’s metamorphosis into a baroque city, confident of its place in the world. Baroque fountains were placed all over the city. Theatrical as well as functional, they reminded people of the magnificence and benevolence of their patrons.

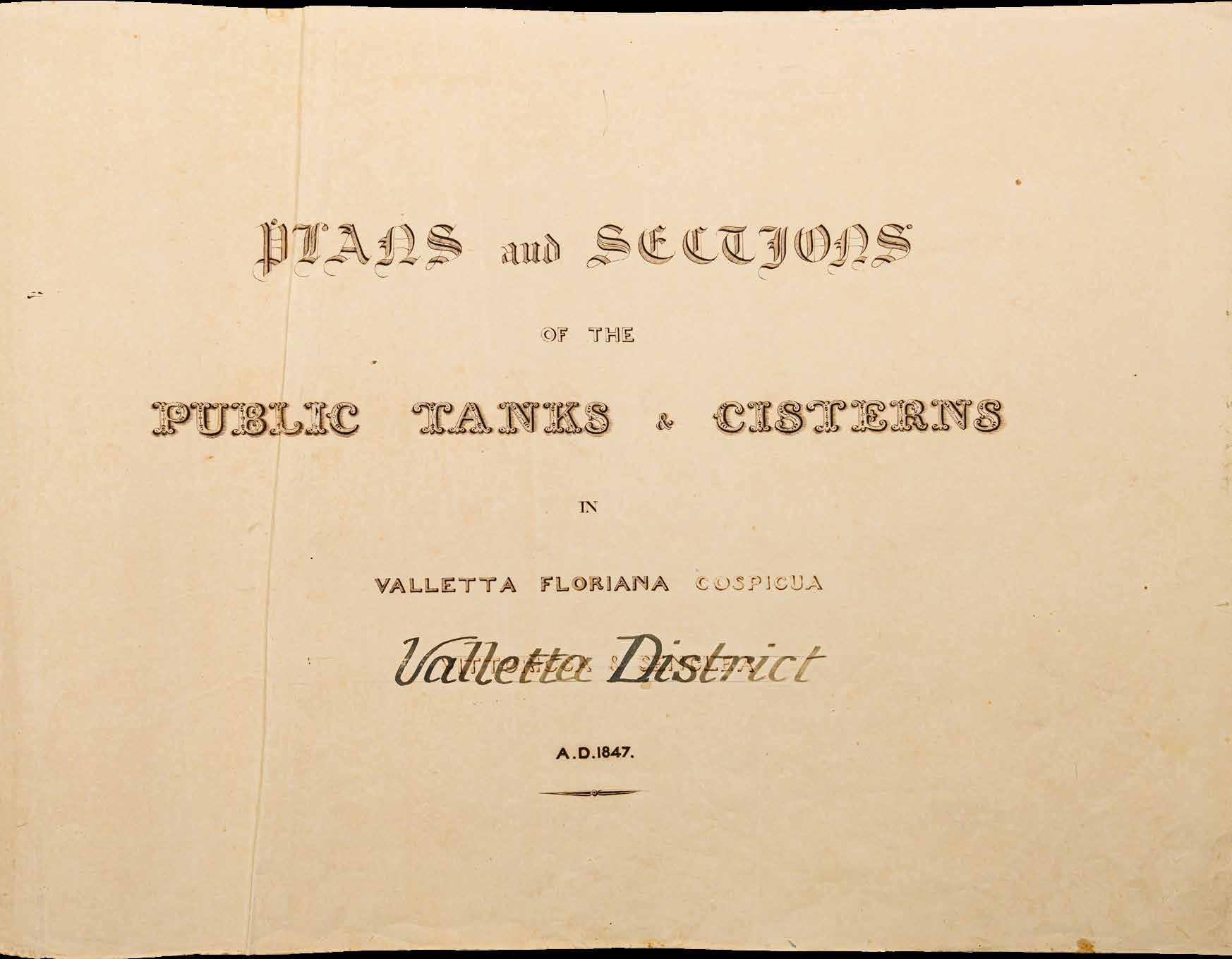

Water was precious. A ‘Direttore delle Fontane’ was put in charge to regulate water supply; ensuring that the reservoirs in Valletta were kept full, public fountains were supplied, and that various key buildings, such as St John’s Co-Cathedral, the Sacra Infermeria and the bakeries had their required share. A report by the Italian architect Romano Carapecchia about all the public and private water cisterns and reservoirs in Valletta and the Three Cities, presented to Gran Master Vilhena in 1723, listed 13 public reservoirs and 40 public cisterns containing a total of 39,584 botte (approx. 37,6 million litres) in Valletta.

The fear of a siege meant that the Order could never solely depend on the aqueduct for its water supply. If attacked, it would be too easy to sabotage the aqueducts. Carapecchia stressed the need of collecting all rainwater from streets, house roofs and terraces; to build reservoirs adequately protected from artillery fire, and constantly supervise private wells to ensure they were always in a good state of repair.

Ironically, the efficiency of Valletta’s water supply was never put to the test by the Order, who were evicted from the Islands by Napoleon in 1798. Within three months, the Maltese rose up against the French who retreated behind Valletta’s secure walls. The cisterns and reservoirs would provide for the besieged French until their surrender two years later, when they capitulated to the British forces who had come to the aid of the Maltese. With this episode, a new chapter in the Islands’ history had begun.

During the 19th century, Malta was transformed into a British fortress colony. The Islands became the main base for the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, serving Britain’s global strategy to control trade routes and shipping. Much economic growth was concentrated around the harbours. The British invested heavily in the Dockyard which was based in Bormla, while Valletta developed into an important trading hub.

The capital city saw a spurt of businesses catering to the Navy and Services, including the infamous entertainment district in Strait Street. The Naval dockyards and growing service industries drew people in from the countryside, putting huge pressure on the water infrastructure around the harbours. Indeed, the 19th century would see a complete overhaul of Malta’s water supply, drainage and sewerage systems, paving the way for the growth of suburbs radiating around the harbour region.

The first decades of the 19th century were plagued by insufficient water supplies, poor water quality and regular outbreaks of water-related diseases, such as bowel complaints, fevers, typhoid and cholera. The harbours are reported to have become giant cesspits through the raw sewage that poured into them. In the 1870s, the Royal Navy pressed upon the authorities the need to divert raw sewage outside the harbours, complaining that the stench of the Dockyard Creek was insupportable for the workers, officers and people living in the vicinity, as well as putting people’s lives at risk.

Leaching cesspits and conduits were another source of water contamination. In 1867, Dr John Sutherland reported that in an examination of water storage tanks:

“in not a single instance was the water drawn from these tanks at the time of this inquiry fit for cooking or drinking. It was generally discoloured and more or less offensive both in taste and smell.”

Sutherland recommended against storage in underground tanks because of the risk of contamination and because they caused rising dampness.

The last quarter of the 19th century saw a complete overhaul of Malta’s water infrastructure. There was a shift from dependence on public and private rainwater cisterns to supplying potable water via iron pipes, decreasing the possibility of contamination. Water supply was increased by tapping into new water sources such as springs and sea-level aquifers. Plans were also laid out to carry sewage outside the harbours to the open sea where currents would dissipate the outflow. The British civil engineer Sir Osbert Chadwick designed a complete overhaul of the sewerage system of the fortified cities in the harbours where, due to the scarcity of fresh water, seawater would be pumped through iron pipes to flush out sewage. The Central Power Station lifted sea water up to a tank in St James Cavalier while gravity would channel it to Valletta’s sewers. In 1903, it was estimated that the new system had increased the

quantity of water available for flushing purposes from 63,000 gallons a day to 500,000 gallons a day.

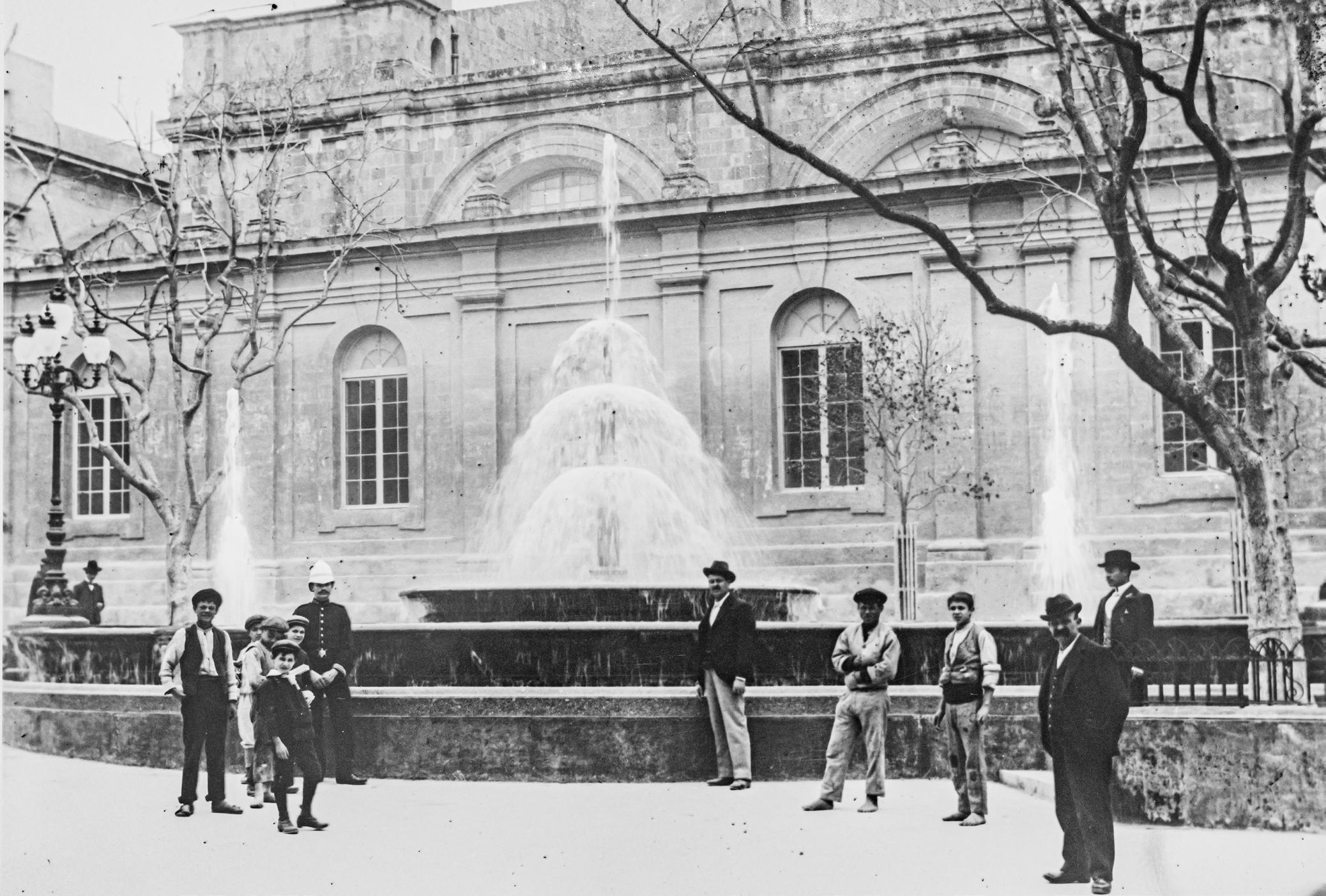

Proud of the success of the new salt-water flushing system, the Superintendent of Public Works, Lorenzo Gatt proposed building a saltwater fountain in the square directly above the Underground Valletta reservoirs. The fountain was erected along the pipeline to St Elmo’s ditch and acted as a distributor to the various heads of the systems of sewers in Valletta.

Opposite: Title page of an 1847 PWD Report surveying the water storage capacity in Valletta. (PWD);

Opposite: Title page of an 1847 PWD Report surveying the water storage capacity in Valletta. (PWD);

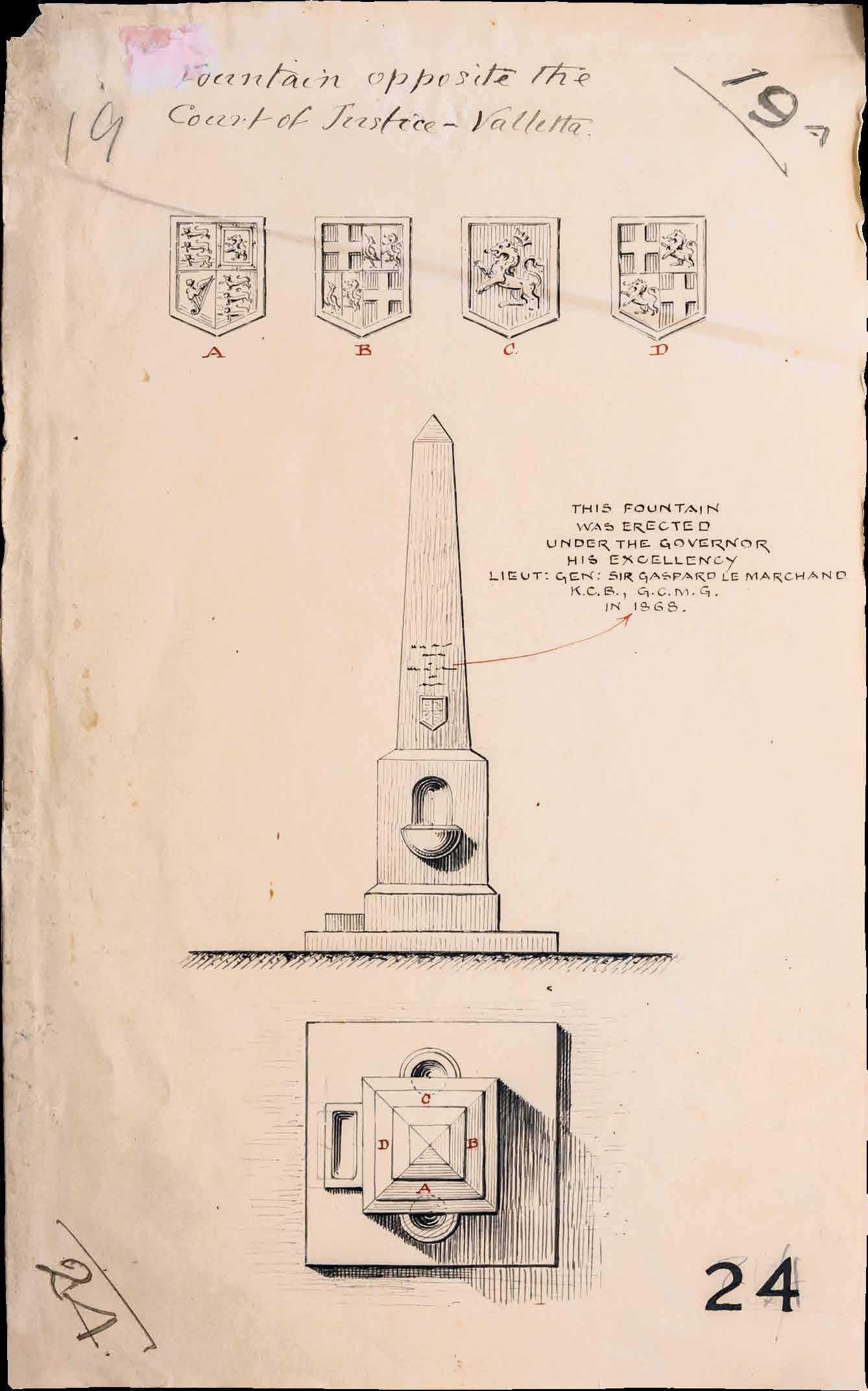

The square in front of the Law Courts seems to have captured the imagination of the Public Works Department (PWD), and various designs exist from around 1860 for its embellishment.

One proposal seems to incorporate the bronze Neptune statue that had originally stood at the Valletta waterfront. However, the PWD appears to have settled for a more practical design for a drinking fountain. PWD plans show a fountain surmounted by an obelisk. Besides providing drinking water for humans, it was also to be furnished with a small trough at its foot to permit animals to drink from it. At the beginning of the 1900s, it appears that the obelisk fountain was replaced by a new fountain fed with seawater.

Early 20th-century photos show the new fountain cascading several tiers of water way above the heads of people standing nearby. The new fountain proudly displayed the abundance of seawater recently

introduced with the new seawater flushing system for Valletta. Unfortunately, the seawater fountain ran into difficulties within a few years. Seawater caused the fountain mechanism to deteriorate quickly. There were also mounting concerns about the effects of salt on the neighbouring buildings, including the side of St John’s Co-Cathedral which overlooked the fountain. Apparently, the fountain also managed to irk some people at the Law Courts across the road, who complained about the noise it made. Eventually, in 1923, it was proposed that the seawater fountain is decommissioned and replaced by a national monument. The fountain was finally dismantled in 1926.

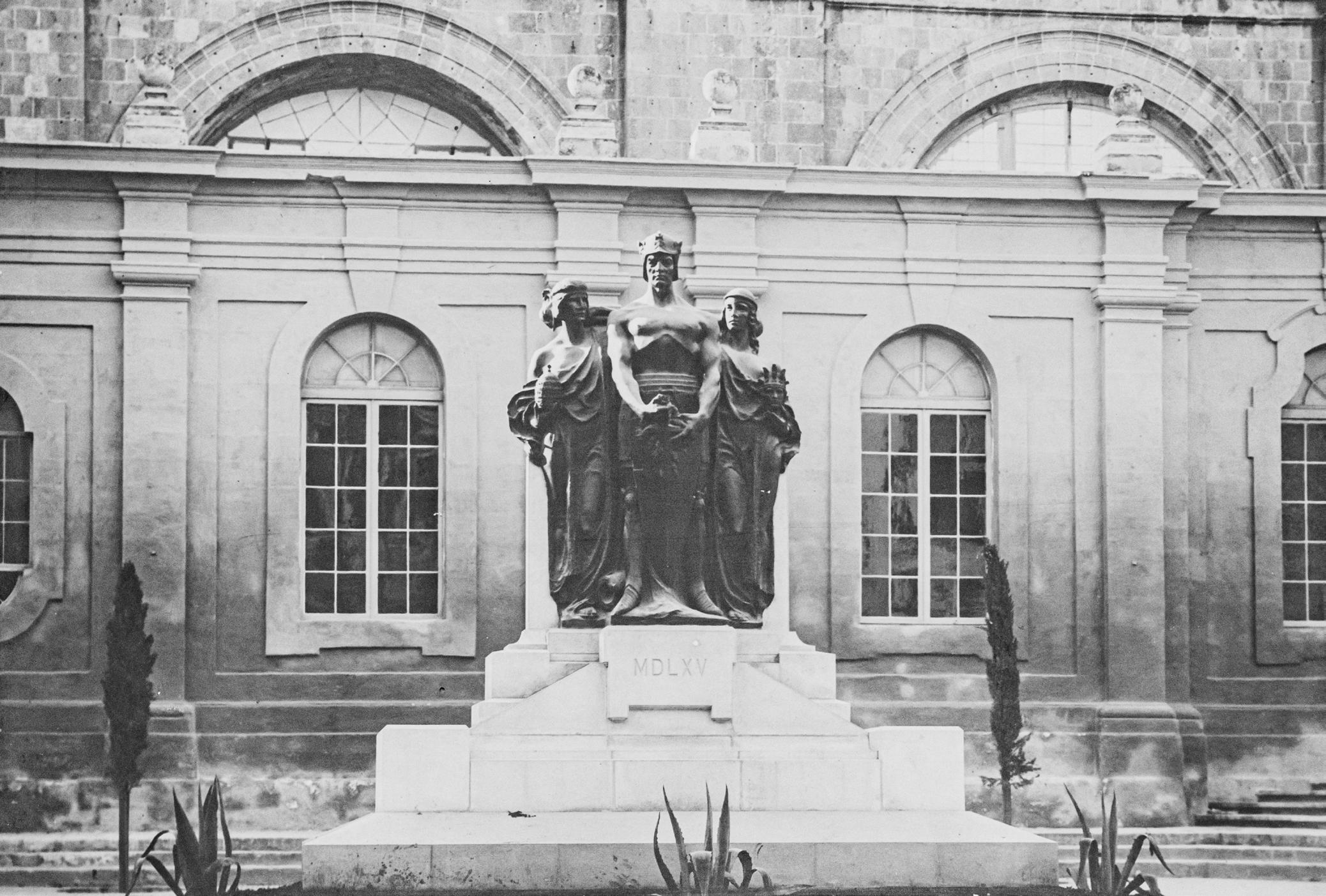

The commission for a new national monument was designated to the Maltese sculptor, Antonio Sciortino. His monument commemorating the Great Siege of 1565 consists of three bronze figures symbolising Faith, Fortitude and Civilisation, standing on a granite base. This national monument still stands in front of the Law Courts. Every year on 8 September, wreaths are placed at its foot to commemorate the lifting of the Great Siege.

Original drawing of the obelisk drinking fountain. Interestingly it dates the erection of the fountain to 1868 – three years after Le Marchand had stepped down as Governor. The date appears to be an error, perhaps a note added to the drawing during the removal of the fountain around 1900. The fountain may have been moved to San Anton Gardens which has a fountain of identical design to that of the drawing, except that the date on the engraving reads 1860

Above: Photo of the saltwater fountain in front of the Law Courts. (NMA)

Above: Photo of the saltwater fountain in front of the Law Courts. (NMA)

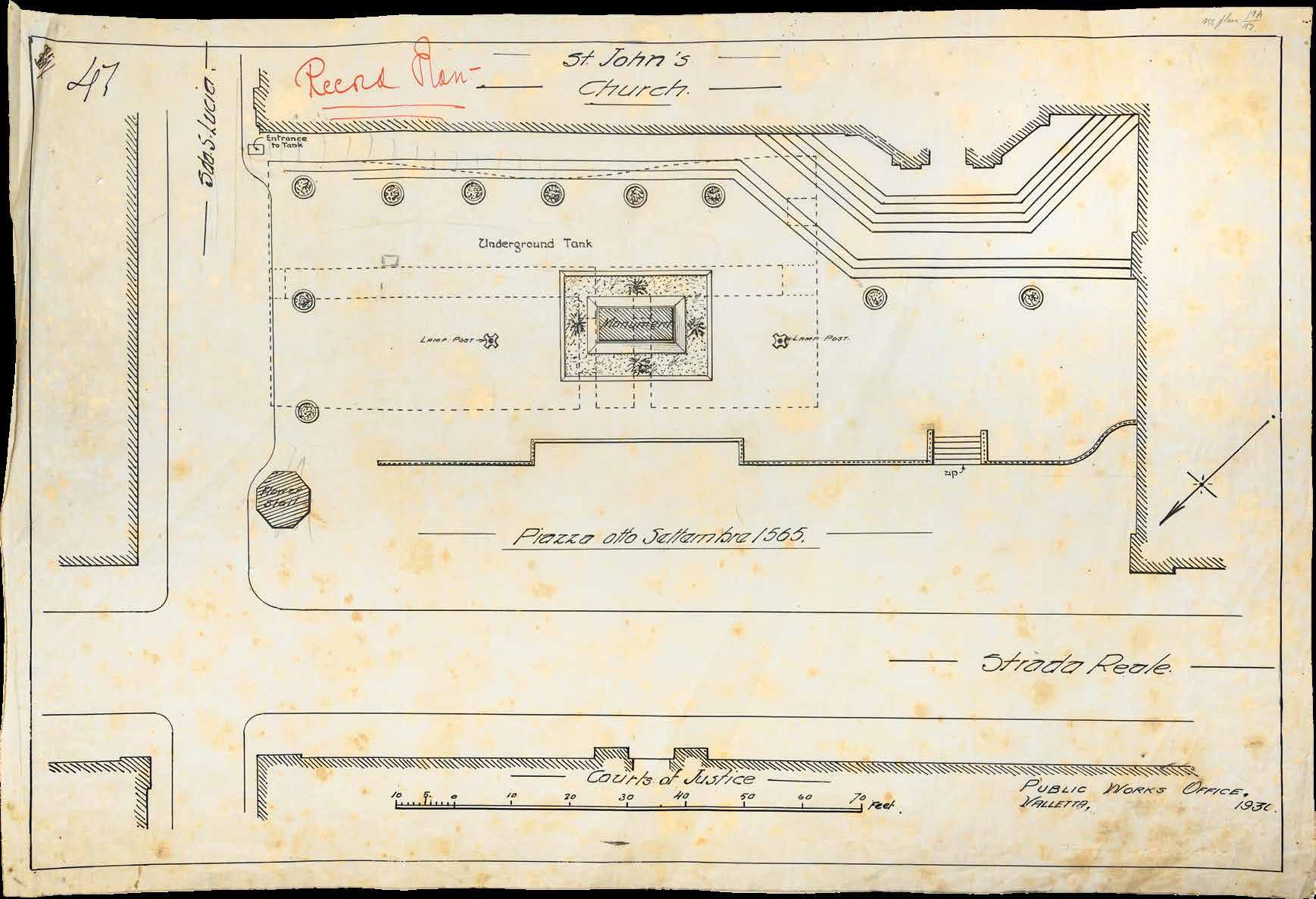

By the early 20th century, it appears that the large reservoir in front of the Law Courts was no longer being used to store water. The Great Siege Monument was built directly above the main wellhead over the reservoir’s sump pit. A possible motive for this position is that it made structural sense to place the monument on the reinforcing arches, over the wellhead, to bear the heavy load of this monument since this is the strongest part of the vaulted ceiling. Photos show that the saltwater fountain had also covered the opening into the reservoirs when constructed in 1902.

A plan of the Great Siege Monument dated 1930 shows a breach in the eastern corner of the reservoir to create a new entrance. Today, this opening is covered by a ramp for wheelchair access into St John’s Co-Cathedral. A spiral stone staircase that still exists, was built here to access the reservoir. Interestingly, the plan also shows a long narrow tunnel that led towards the low-lying streets on the Grand Harbour side. This tunnel may have been cut to drain water from the reservoir when it was no longer in use.

These underground spaces would soon take on a whole new significance as World War II loomed like a dark cloud ready to unleash death and destruction over the Islands.

Driven into the dark, damp tunnels burrowed beneath the City in order to escape bombing, it is remarkable that people maintained some degree of sanity during Malta’s blitz. These shelters became a symbol of fortitude and defiance for the Maltese in the face of the enemy, knowing that the wide stretch thickness of rock above their heads was virtually impregnable.

Due to Malta’s proximity to Sicily with its impressive air force, the Regia Aeronautica, and navy, the Regia Marina, Britain doubted it had the military capacity to take on Italy if it were to attempt a full-fledged invasion of Malta. In April 1939, the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet was moved from Malta to Alexandria in Egypt, as this was deemed to offer a more secure base.

Government propaganda aimed to keep up morale against the enemy and to convince people of the righteousness of keeping Fascism at bay. The authorities also set up new organisations such as the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) and the Demolition and Clearance Department. Between 1935 and 1939, the population was introduced to curfews, blackouts, putting on gas masks and Air Raid Warning practice.

Existing underground spaces such as catacombs, church crypts, wells, basements and existing tunnels, were cleared out. Plans to dig out new rock shelters were concentrated in high-risk areas such as the harbour area where the HM Dockyard was located, and villages next to the aerodromes. Of particular concern to the authorities was the density of the population in the fortified cities. The population of Valletta in 1940 was over 22,000. Many of the streets in the old cities were quite narrow and risked becoming blocked by heavy stone masonry should buildings get bombed. This meant that emergency services risked not being able to recover the injured or dead.

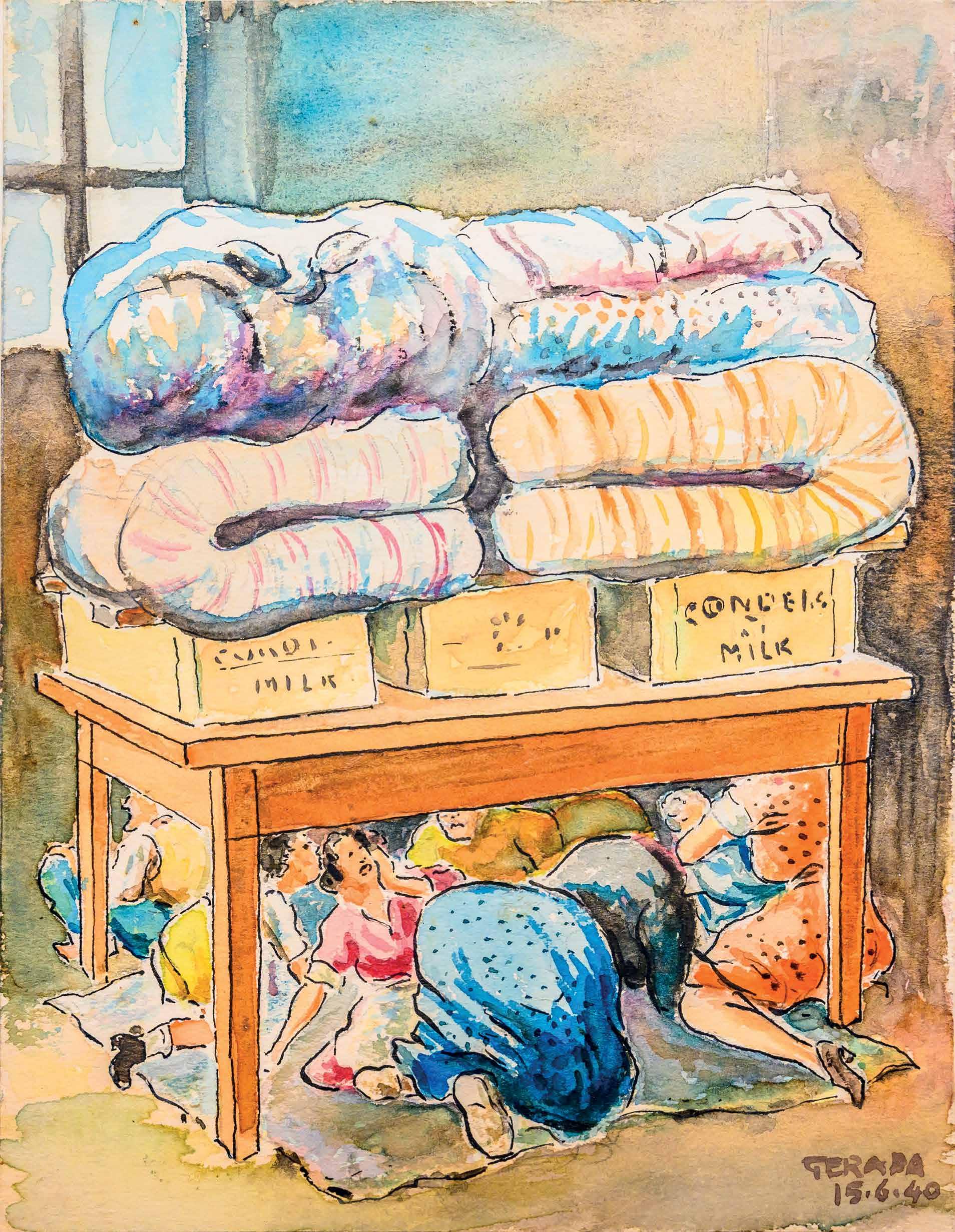

Initially, the Government advised people to improvise shelters by placing mattresses on tables and hiding under staircases. Meanwhile, preparations were made in low-risk areas to receive refugees from those deemed high-risk, should Malta be attacked. Despite precautions, nothing could quite prepare civilians for the reverberations of those first bombs.

Malta was desperately ill-equipped to defend itself when Mussolini declared war on Britain on 10 June 1940. Malta’s defences were essentially 34 heavy and 8 light anti-aircraft guns, and 4 obsolete Gloster Sea Gladiator bi-plane fighters. On 11 June, within hours of Mussolini’s declaration of war, the Italian Air Force, the Regia Aeronautica, dropped the first bombs on Malta.

An excerpt from Christina Ratcliffe’s memoirs describes the confusion of the first attacks:

“no one in my street [Floriana] was left… they had all gone down to their cellars… most of them sat under the stairs. Best place in the house, absolutely fool-proof. That is what they believed in the first few days ….” (Galea F. R. 2006)

Ratcliffe described how by the evening hundreds in Valletta and Floriana had carried bedding and seating to the existing shelters. These included the Old Railway tunnel and the Knight’s tunnels in St Andrew’s bastions. The next day, thousands left the harbour cities for safer areas inland.

The Italians did not press home their advantage. Despite continuous air raids, the Italian bombers flew at a high altitude to avoid the anti-aircraft guns, compromising accuracy for personal safety. Meanwhile, Mussolini had turned his attention towards Greece and Egypt. This gave Britain the opportunity to send military reinforcements to Malta, and in early August 1940, the first Hurricane fighters arrived.

For the next three years, Malta’s fate would be closely tied to the developments in North Africa. As Germany and Italy advanced in North Africa, they required more and more reinforcements from Europe. In December 1940, German military airplanes, the Luftwaffe

arrived in Sicily to assist Italy after defeats in Greece and North Africa. German air raids were devastating and changed the face of the harbour areas. The Luftwaffe divebombers were able to drop bombs from lower altitudes to find their targets with greater precision and did not limit themselves to military targets. All of Malta felt vulnerable.

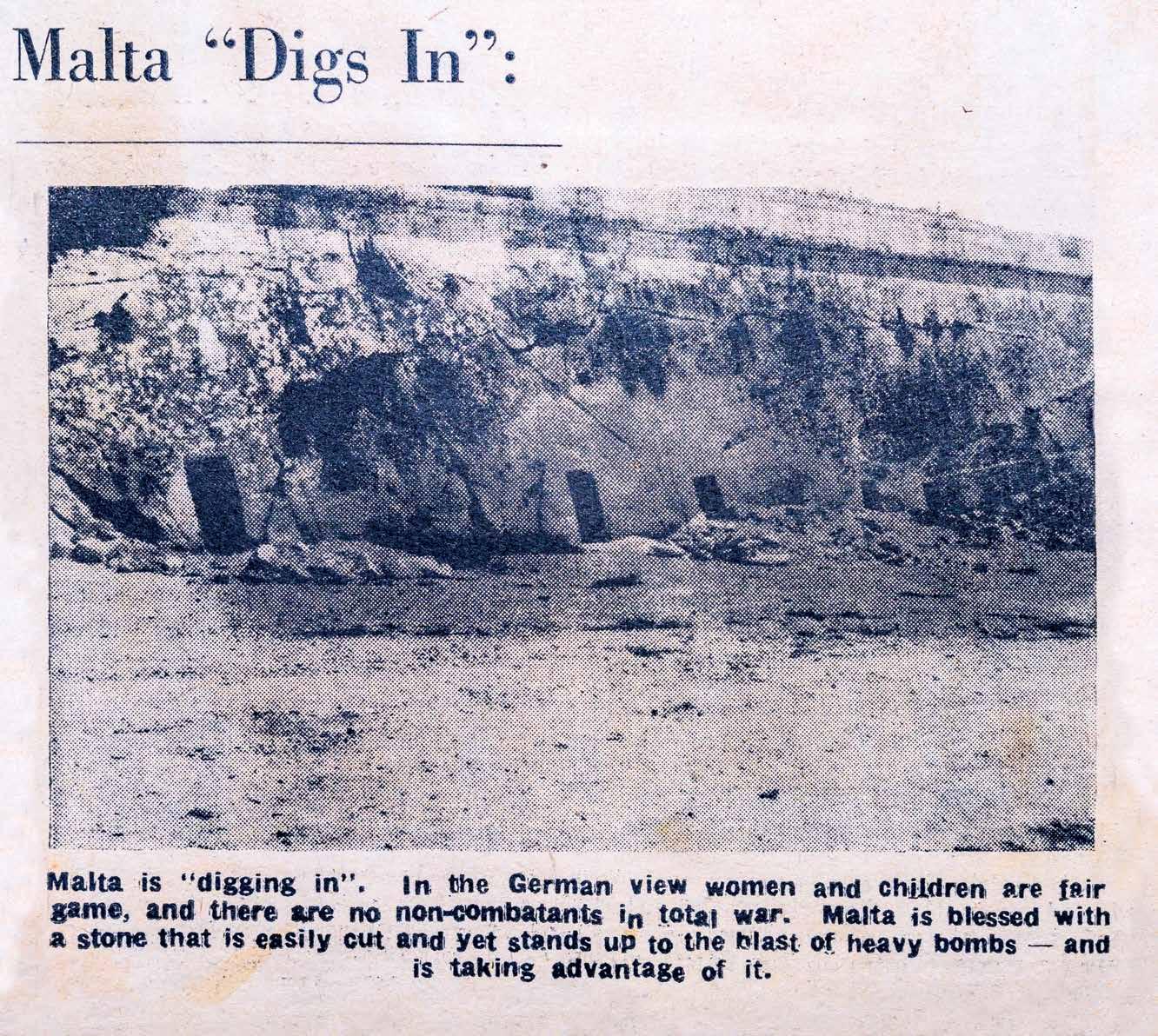

In January 1941, the arrival of the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious for repairs in Malta’s dockyard drew a sustained German blitz of unprecedented ferocity over the Grand Harbour. Senglea suffered heavy casualties as bombs reduced the town to piles of rubble. After what became known as the ‘Illustrious Blitz’, the only shelters the Maltese considered safe were rock-cut shelters. Two departments were responsible for providing shelters, The Public Works Department (PWD) and the Supervisor for Shelter Construction. The PWD was responsible for digging shelters in evacuated areas, such as the Harbour cities. The Government mobilised miners and requisitioned mining equipment in the drive to provide everyone with access to shelters. The authorities also began to manage food supplies, anticipating a long-drawn-out siege.

Communities mobilised their citizens to assist in the construction of shelters, including women and children. By 1 November 1941, there were enough shelters on the Islands for 270,332 people, offering 2 square feet per head of the population. The total cost ran at £600,000. Enough shelters also emboldened many to return to their homes in the harbour areas.

The Public Works Department (PWD) hacked through Valletta’s underground spaces, connecting wells, cellars, crypts, bastions, tunnels and basements to carve out a system of tunnels that could shelter the inhabitants of the Harbour area. People clamoured for the security that rock shelters could provide. The Press lent weight to the urgency for rock shelters. On 2 July 1940, the Times of Malta editorial wrote:

“There are… underground spaces… under 8th September Square, and tradition has it that some of the stone for the construction of St John’s Co-Cathedral, was cut on the spot, and the quarry thus formed turned into a reservoir for use in case of siege. These wells almost touch each other; it is thought that several of them are connected, and those which are not can be joined by tunnels at little cost.”

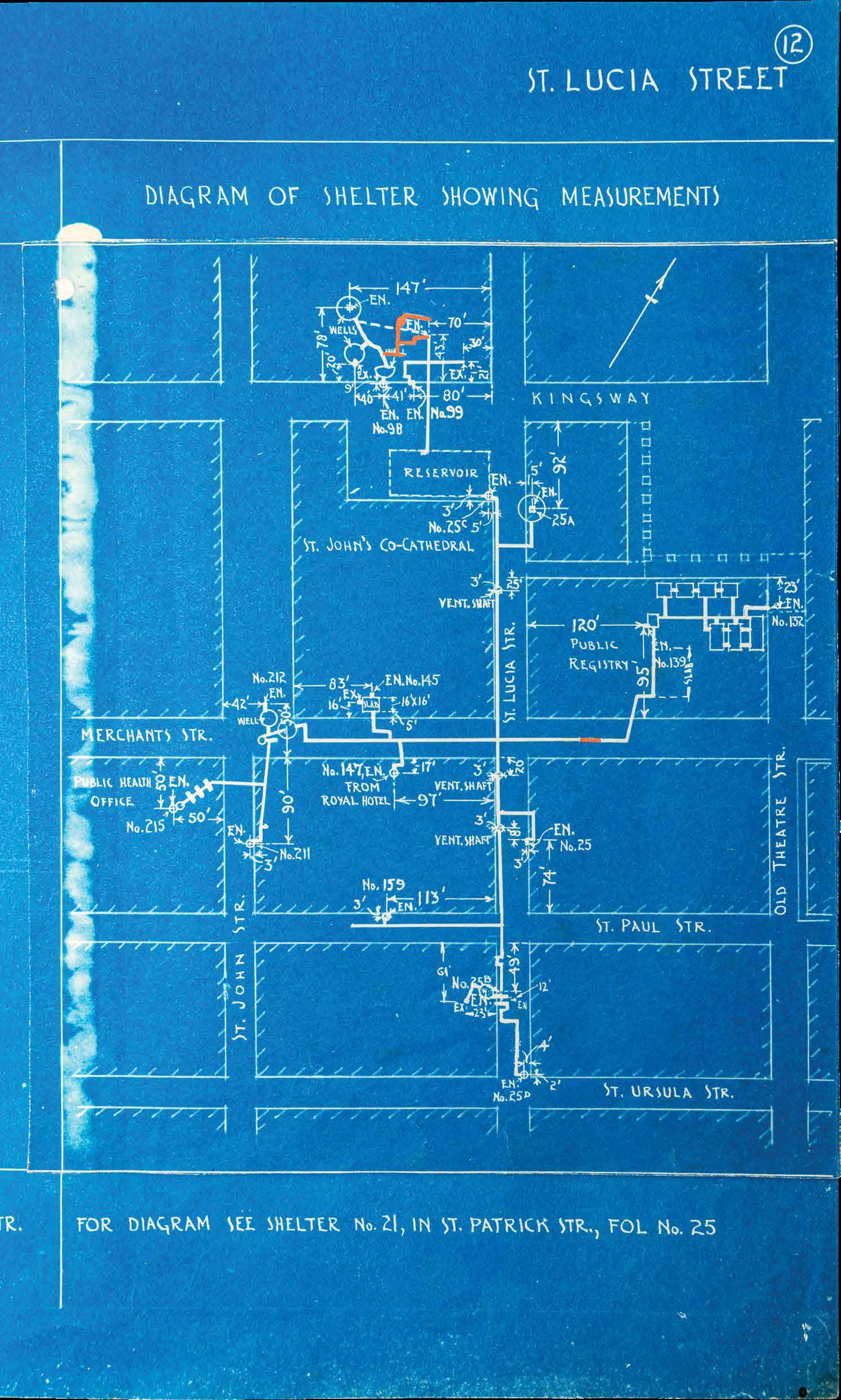

The Times of Malta was referring to the reservoirs in front of the Law Courts which form part of the network of Underground Valletta. These reservoirs soon became part of one of the largest shelter complexes in Valletta.

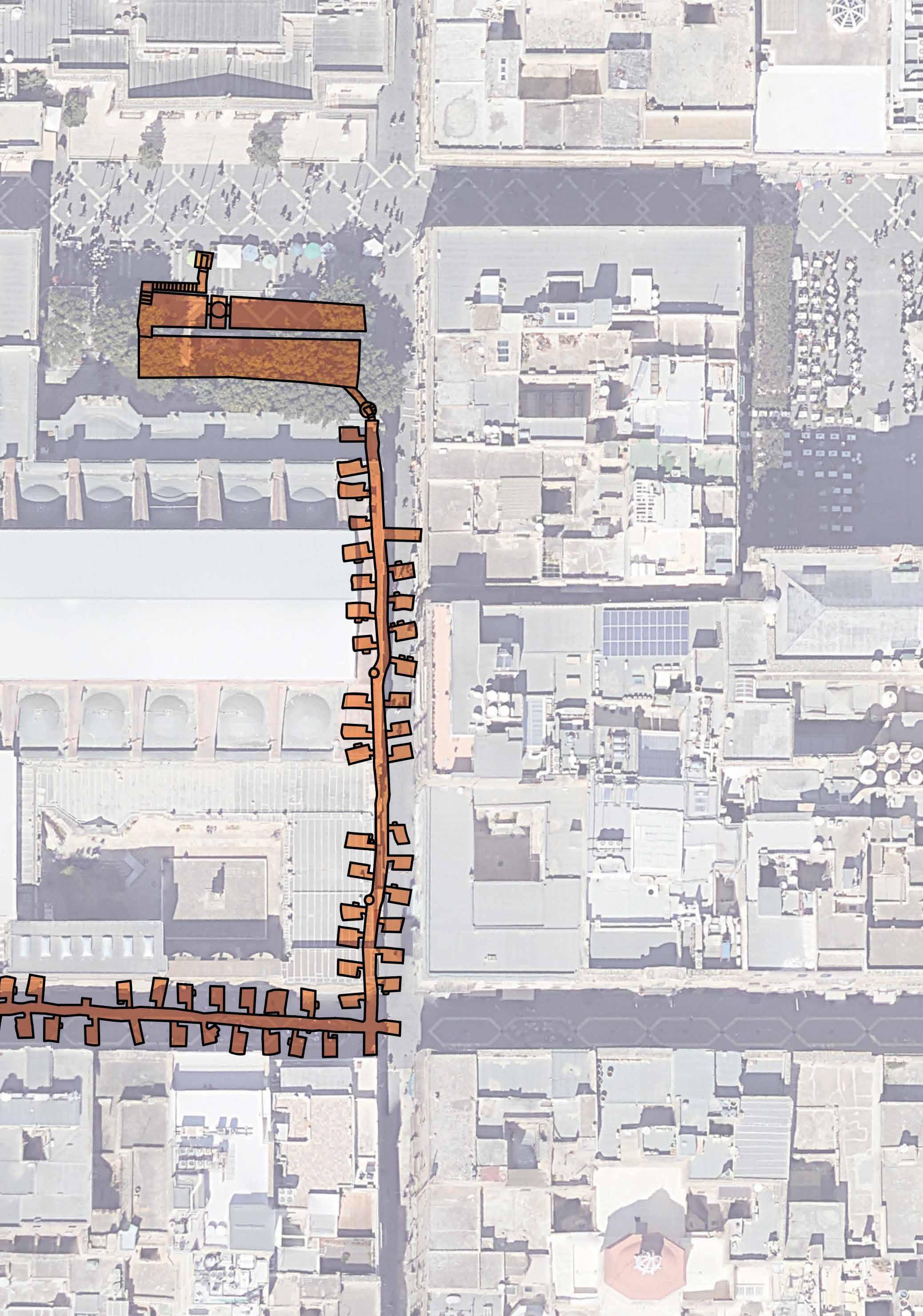

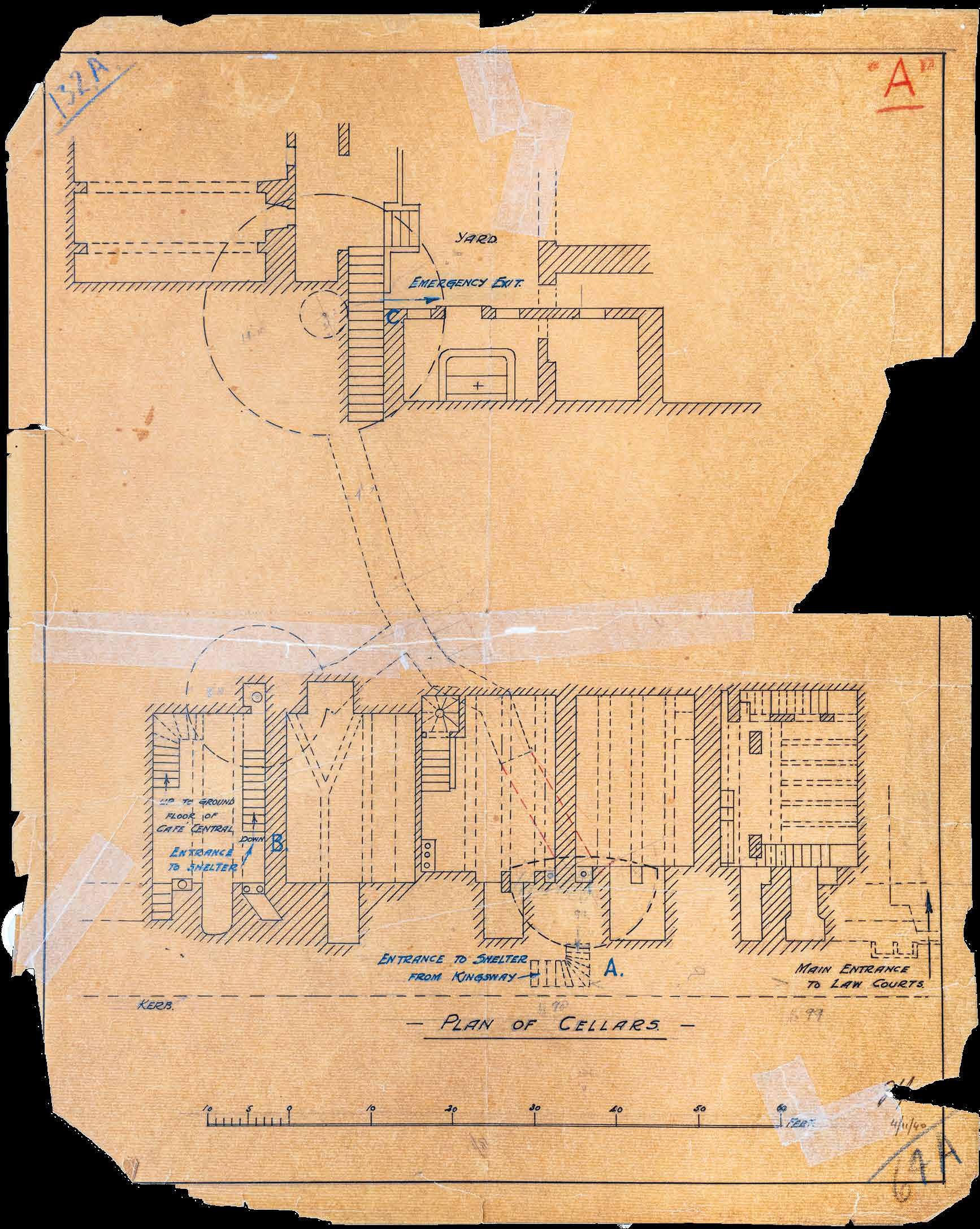

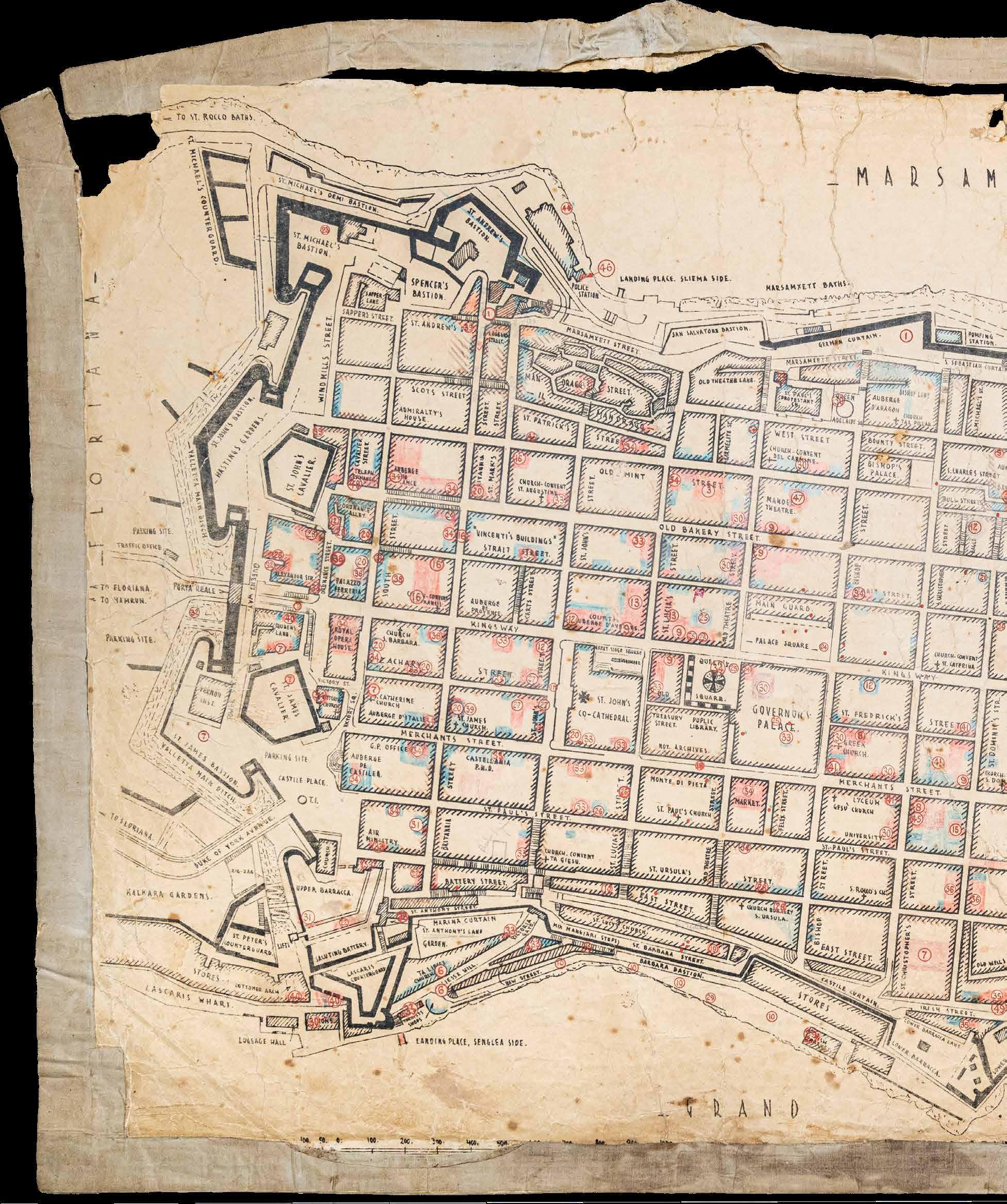

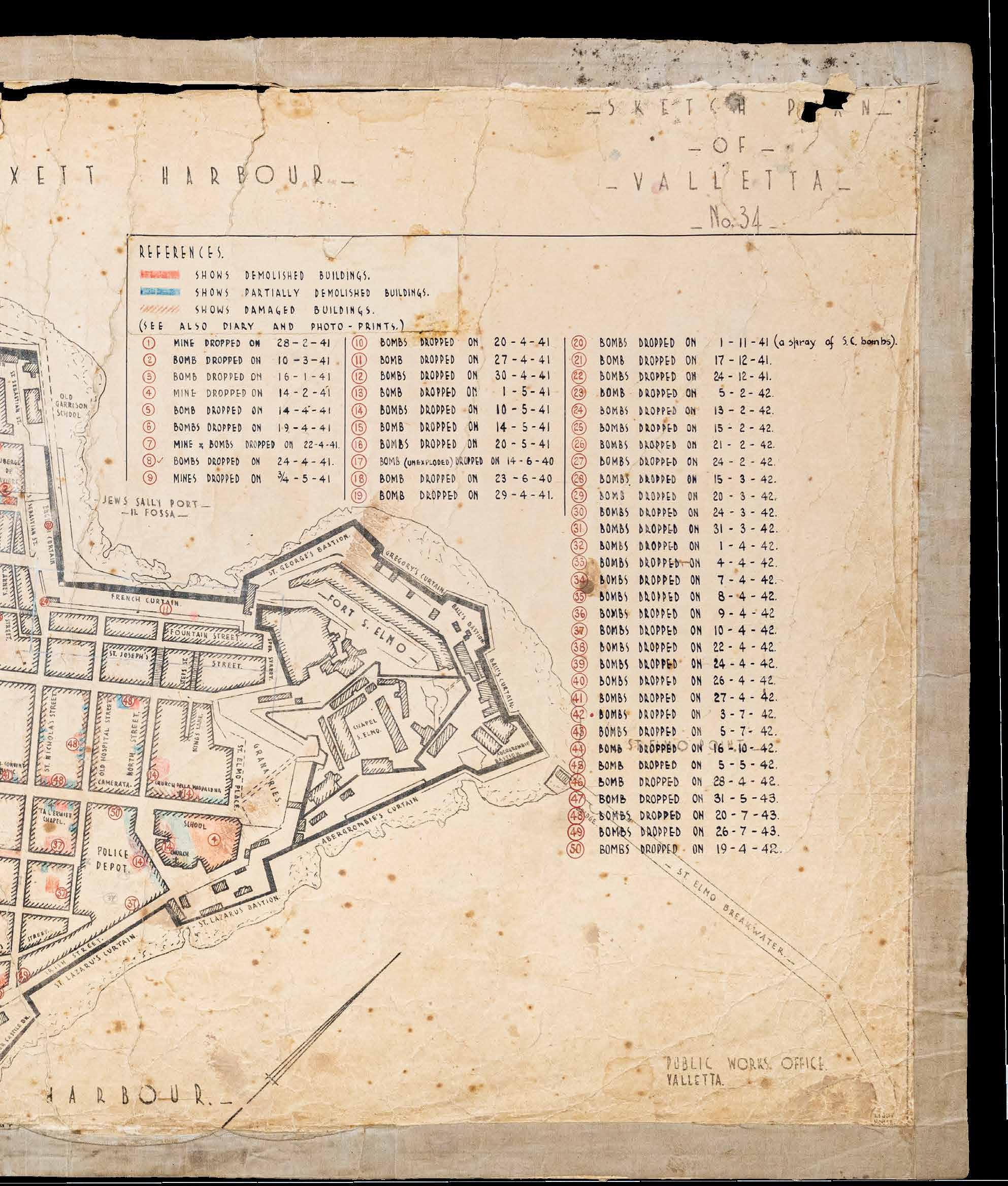

PWD diagrams of the shelters, reproduced on pages 47 and 48, show that a tunnel was excavated beneath Republic Street connecting the Law Courts to the reservoir. The breach was walled up after the war but can still be seen behind the recently built metal spiral staircase, pictured in page 49, when exiting the reservoirs onto Republic Street. A stone staircase was built within the reservoir to permit people entering from the Law Courts to descend to the bottom of the reservoir. The date 1941 is scratched into this staircase. From the reservoirs, the PWD excavated tunnels directly below the streets, connecting the tunnels with private shelters and other entrance and exit points. The PWD diagram on page 47 shows how they exploited the relatively level ground to reach different streets and public buildings located in Valletta’s centre. Worth highlighting are:

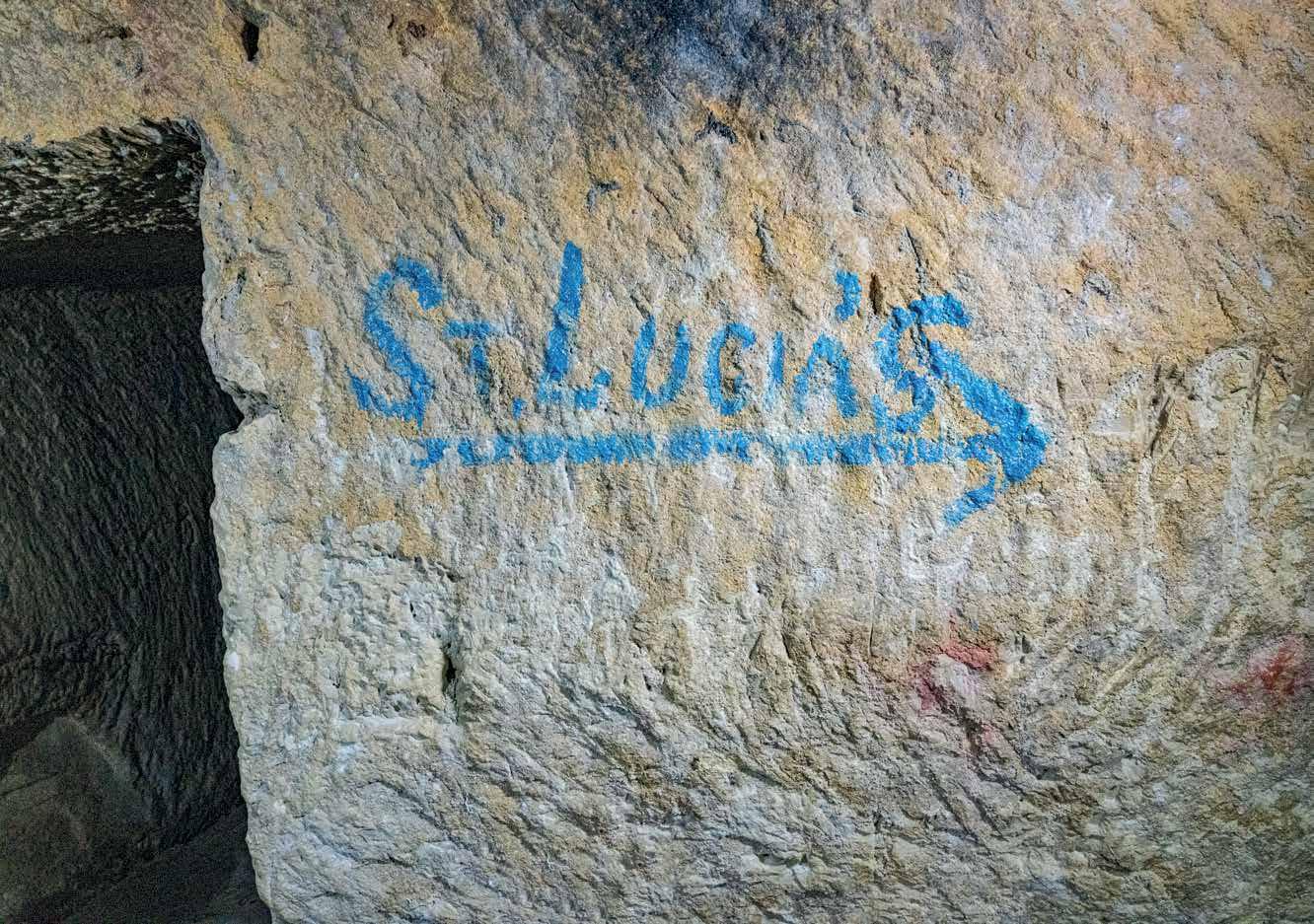

the entrance in front of St John’s Co-Cathedral; the spiral staircase pictured in page 49 that permitted entry from street level in St Lucia Street;

tunnel beneath Republic Street connecting the Law Courts to the reservoirs.

Many entrances were sealed off after the war. The Underground Valletta experience extends from the points marked a to c on the plan, leading one through over 200 metres of breached cisterns, steps and corridors. Entrances and exits were given their own unique number to facilitate their maintenance and management. This was also crucial to allow rescue operations should some of the entrances get blocked by masonry from bombed buildings.

Above: Plan of the underground spaces that were exploited to create shelters beneath the Law Courts. It also shows the passageway connecting the Law Courts and the reservoir (PWD).

Above: Plan of the underground spaces that were exploited to create shelters beneath the Law Courts. It also shows the passageway connecting the Law Courts and the reservoir (PWD).

Quite incredibly, the technology to excavate the war shelters had not changed much from the time of the Knights. A pick-axe would demarcate the area to be excavated and a large metal wedge would be inserted into the deep groove. This in turn would be struck by a mallet to break off chunks of rock. One or two miners would excavate, while the debris would be shovelled into a wicker basket by a labourer and carried out. The diggers worked by lamplight in the depths where daylight never reached.

The shelter walls still show the marks made by pick-axes. On close observation, these tool marks can follow the circular movement of the swing of the miner’s pick-axe. The tunnels of the shelters follow the same street plan above ground. The street names were marked in blue paint at the crossroads of interconnecting corridors for orientation.

Along St Lucia Street, the miners started from the reservoir end, widening the pre-existing tunnel referred to in page 40. At the corner of Merchant Street with St John Street, miners cut through two cisterns to create a staircase to reach the tunnel leading to the reservoirs. The entrance to the staircase was shielded by a shelter hood (pictured on page 52).

Shelter hoods were constructed at shelter entrances to give some protection from the blast of bombs.

Above: Bomb damage around the entrance to the shelter from St John’s Street. Notice the shelter hood in front of the gazebo that still exists.1942.

Photographer: JE Russell.

Courtesy:Imperial War Museums;

Right: World

An effective administrative system was implemented to manage the shelters. The District Commissioner was responsible for the safety of the people in his district: building new shelters, requisitioning property for shelter use, maintaining shelter upkeep which included regular cleaning, and giving people permission to take up residence in a shelter. In the management of shelters, the District Commissioner was assisted by the Supervisor of Shelter Construction, shelter wardens, cleaners and the police. In Valletta, the main shelters were equipped with basic amenities such as electricity, lavatories and wash-hand basins. As the war progressed, water and electricity supplies were disrupted as water pipes became damaged and fuel supplies dwindled. Along the walls of Underground Valletta, one can still observe blackened holes that would have held candles or homemade lamps which burnt kerosene, or even lard or vegetable oil when kerosene became scarce. Electricity fittings still hang from the walls of the corridors and a broken sink is still in place, built directly beneath a ventilation shaft.

The Chief Medical Office monitored people’s health and published monthly statistics of afflictions and diseases. Vaccination campaigns helped ward off some transmittable diseases such as diphtheria. Damage caused to water mains and sewage systems by bombs led to several outbreaks of typhoid. With limited access to water and soap, and living in such closed and crowded conditions, contagious skin diseases such as scabies were rampant. Mosquitos, fleas and sand fly added to the occupants’ torment.

Large shelters were also equipped with birthing rooms. These were kept clean and offered basic facilities for the safe delivery of babies as could be managed within shelter conditions. The birth rate fell significantly during the war, reflecting the disturbance to

Without shelters, it is difficult to see how life in Malta could have continued. Providing safety during air raids meant that civilians somehow absorbed the horrors of war into a new kind of reality, combining sheltering from bombs with going about their daily lives. There would be periods of intense bombing followed by a lull, as the Axis would move their airplanes to new theatres of war, lured by bigger prizes, such as North Africa and Russia. In 1940-41, Valletta saw its shops, cinemas and entertainment areas reopen. Children attended school between air raids, even sitting for exams.

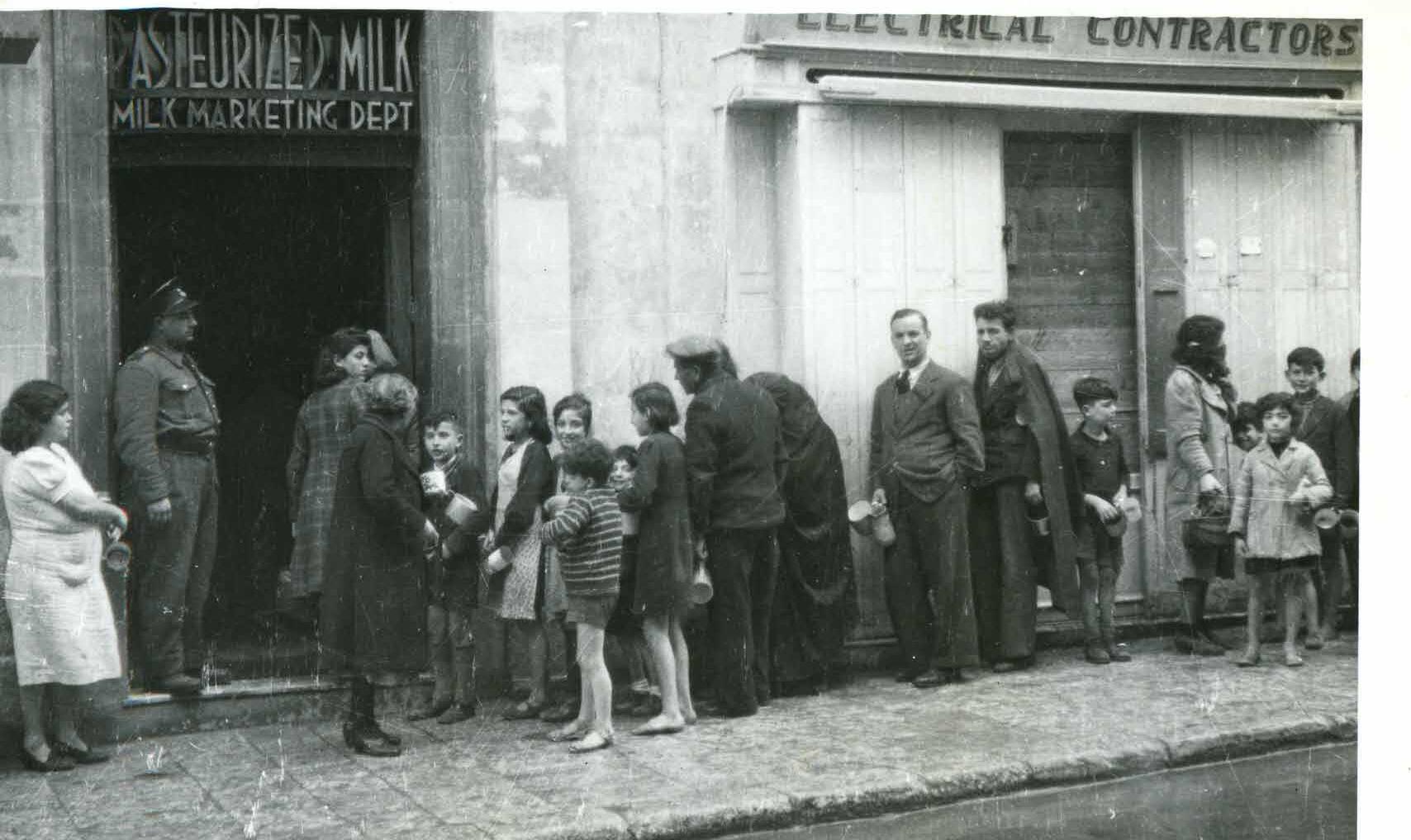

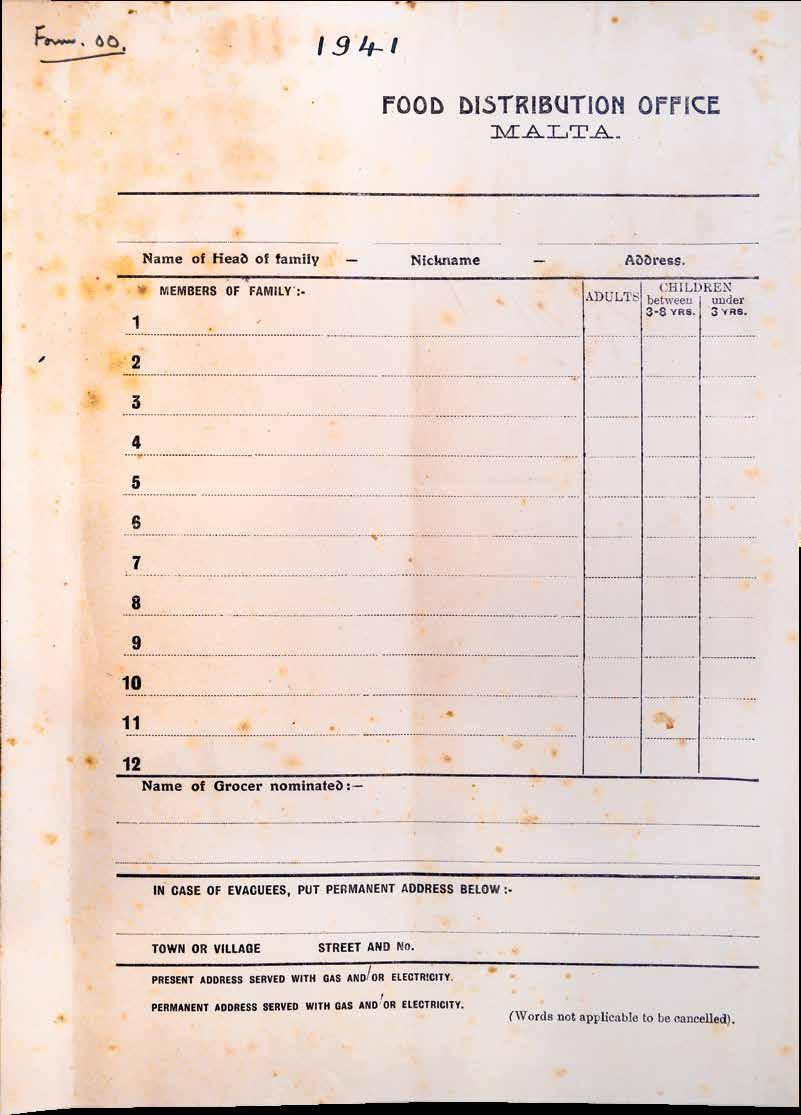

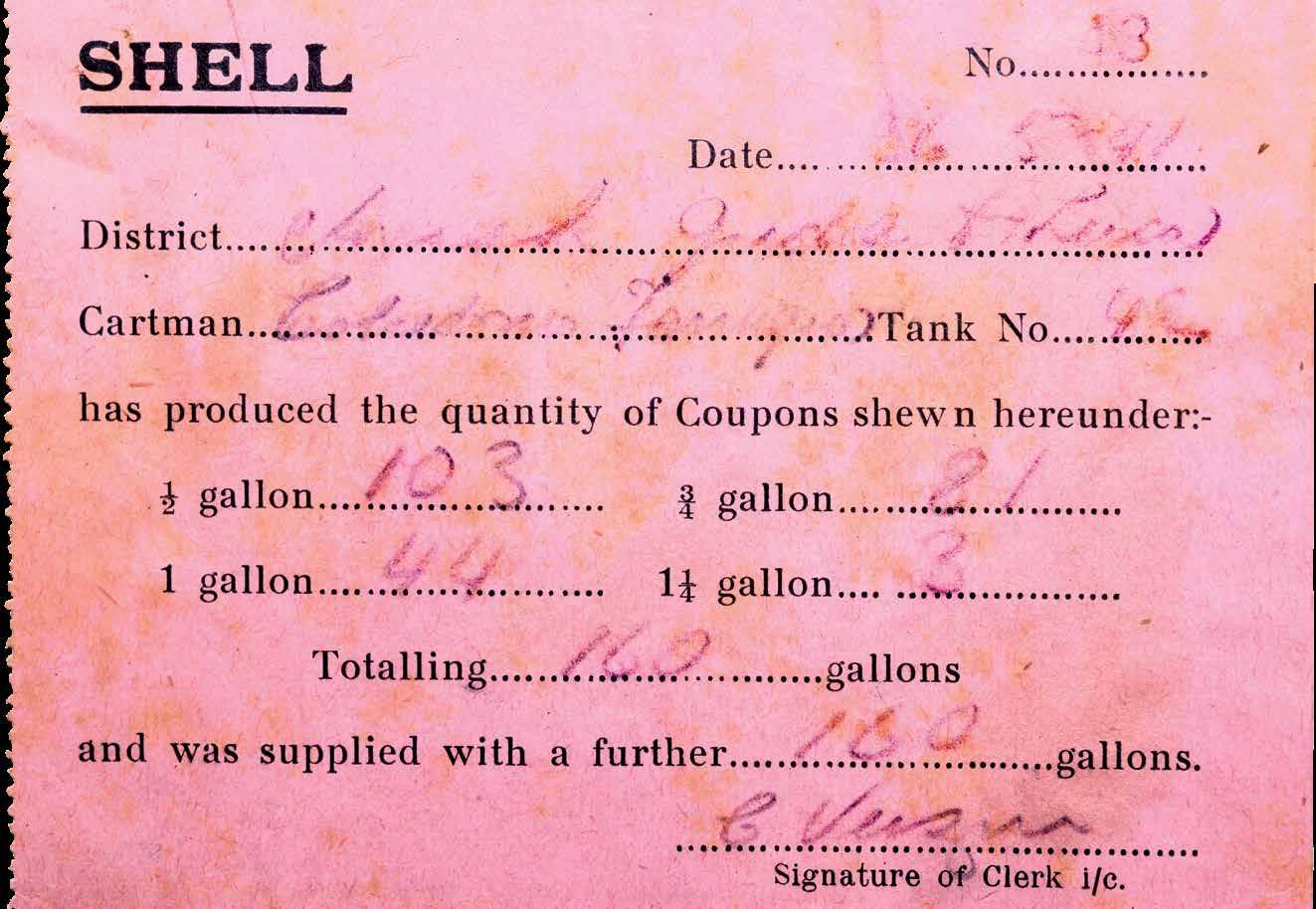

Malta was reliant on many commodities and foodstuffs arriving by sea. With the outbreak of war, supply ships had to navigate through the onslaught dealt by the Axis aircraft and torpedo bombers. As a precaution, rationing became operative on 7 April 1941. The first items to be rationed were sugar, matches, soap and coffee. As supplies diminished, more items were added to the list: milk, frozen meat, edible oil, butter, margarine, cigarettes, corned beef and tinned fish. Soon, kerosene was added to the list and even bread, the staple food of the masses. Some people resorted to finding foods such as eggs at inflated prices on the black market. People also became increasingly inventive in stretching the little they had. Children collected dead fish killed by bombs that fell into the sea. The Times of Malta newspaper pages and propaganda leaflets dropped from Italian aircraft doubled as toilet roll. Jane Spiteri, who was an adolescent during the war, described the situation in April 1942:

“Provisions were running dangerously low… Clothes and shoes were as scarce as food and we had to make do with sandals made of cloth uppers and rope soles. With kerosene being strictly rationed, people took to cooking on the traditional ‘kenur’, a kind of wood-burning stone-stove, using fuel usually obtained from among the rubble of bombed buildings. Smokers used to improvise ‘tobacco’ by drying and shredding vine leaves, sometimes even potato skins… For light we used to make oil-lamps, usually improvised out of an empty milk tin half-filled with kerosene or oil, with a cotton string for a wick; I must have read scores of books by the light of such lamps!” (Mizzi L. 1998)

Ration papers. Note the request for one’s nickname, which could be more familiar than one’s official name.

Above: Auberge D’Auvergne that housed the Law Courts. Its shelters were connected to the public shelters of Underground Valletta. (NMA);

Above: Auberge D’Auvergne that housed the Law Courts. Its shelters were connected to the public shelters of Underground Valletta. (NMA);

When the air raid alert sounded, people would run to the shelters and find a place in the dark damp tunnels. Bombs dropping nearby would reverberate throughout the shelter, pushing suffocating clouds of dust through its tunnels. One can only imagine what people sheltering in Underground Valletta felt when Auberge d’Auvergne, which housed the Law Courts and one of the entrances to the underground shelters, was partly destroyed by a parachute bomb on the night of the 29/30 April 1941.

Mothers took to wetting handkerchiefs with water and putting them over the mouths of their young children to help them breathe. People passed the time praying, chatting, singing, and comforting their young.

A mother shares food with her infant outside an air raid shelter. (NWMA)

A mother shares food with her infant outside an air raid shelter. (NWMA)

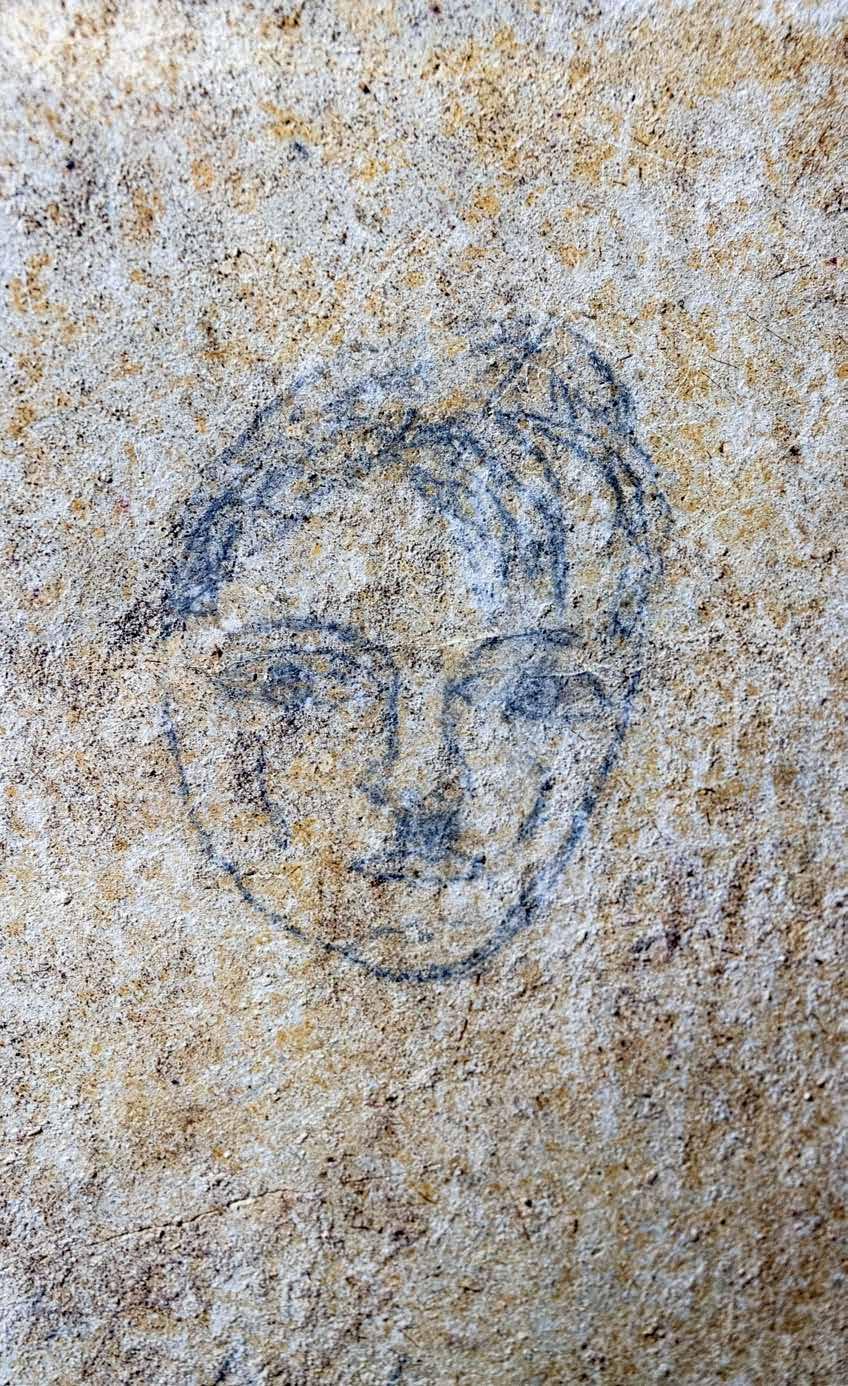

Opposite Above: Shrines to Our Lady; Opposite Below: A carving of the face of Christ emerges from the rock at one of the entrances to the shelters.

Little children even found time to play. Guido Lanfranco, who took refuge in a shelter in Sliema recalled:

“The shelter became our dormitory and I remember scooping the clay out of the rock to make little figures. In the night I used to lead the occupants of the shelter in reciting the rosary.” (Mizzi L. 1998)

Prayer offered comfort and hope to an increasingly battered population. It also offered a source of unity between the young and old. Shelters were adorned with shrines and holy images. Valletta’s largest shelter, in the Railway Tunnel, even had an altar to celebrate mass. In Underground Valletta, there remain a few carvings of the cross and Mary in little rock-cut shrines and broken ceramic shrines.

Of course, relations in the shelters were not always serene. Newspapers reported fights breaking out in shelters over people taking up too much space with chairs and bedding. In 1941, the Government decreed that no one could take down furniture without written permission from a Protection Officer. When night-long raids started in 1942, this decree was suspended, but people were warned it would be enforced if people were ‘unnecessarily unpleasant’ to others.

A theme common to many memoirs of the war is the suffocating feeling of the shelters. Survivors recall that people would attempt to stay closer to the entrances and exit points because of the stifling stench in the inner corridors. Smoking was forbidden in public shelters. Still, Suzanne Parlby recalled “a prevalent smell of garlic, urine, sweat and cigarettes” (Holland J. 2003) in shelters where she took refuge.

The shelters were to some extent also a social leveller, bringing together people of different classes. Parlby described that since there

were no toilet facilities in a hotel’s underground shelter where she took refuge, she was perfectly capable of hanging on all night if she needed to go to the toilet while she was slightly horrified to find the Maltese simply did whatever they needed to into a bucket.

Underground Valletta also offers a lighter side to life in the shelters. The plastered walls of the water cisterns in St John’s Street are covered with pencil graffiti. Among them are caricatures of Hitler and a man in a suit who might have been a local politician – although he does have a passing resemblance to Neville Chamberlain. Somebody sketched out decorative elements that one would perhaps find on furniture – maybe a carpenter or stonemason planning his next project? Ominously, people also sketched images of death and war, such as skulls and swastikas, aircraft and warships. One of the cisterns has the date 1941 written in red paint on its walls.

For those who did not have the luxury of their own private shelter, a private cubicle dug out in a public shelter could offer some semblance of privacy. The cubicles in Underground Valletta span around 3m x 2.3m x 2m. Each cubicle was meant to accommodate a family. How some of Malta’s large families fitted, one can only wonder. The rusted metal fixtures on the walls show where shelves and bunk beds would have been fixed. There are also remains of hinges in the doorways which held gates into the cubicles. Gates allowed people to lock their belongings inside between air raids. Occupants were required to keep the cubicles clean and to take out all bedding in the morning in order to air them.

Families were expected to pay for the digging of their cubicles. Miners were employed privately after their day shifts to excavate cubicles. This led to accusations that miners were taking it easy during the day to reserve their strength for private work in the evening which was more lucrative. The Government was aware of this problem, however, it continued to issue permits for privately-commissioned cubicles as it was believed this would relieve pressure on the public areas in the shelters.

Each cubicle required a permit from the Supervisors of Shelter Construction and directions from the Public Works Department on what was ‘technically possible’. They would look at factors such as water penetration and flaking stone which could make a cubicle unfeasible, dangerous even. A good example of this in Underground Valletta lies beneath St Lucia Street where no cubicles were built. Its walls are jagged rock faces, and water constantly drips from the ceiling. Stalactites have formed where water penetration is greatest.

The porosity of Globigerina Limestone coupled with the humidity below ground meant that the shelter walls were always covered in droplets of water, resembling a cold sweat. Entrances and exits were kept open rain or shine to let in some fresh air, but this also allowed water to pour in during rainstorms. Cubicles had to be built higher than the public areas to prevent water from getting in. Many shelters were furnished with water pumps to help control flooding. Mobile pumping gangs would be sent to pump out water in shelters that had no fixed pumps. Shelving and bunk beds helped to keep belongings out of the water. But no matter where one slept, everything in a shelter got soaked with dampness. In one cubicle, the dripping must have gotten too much. Sheets of zinc cover the ceiling and walls in an attempt to shield the miserable occupants from excessive dripping. On the floor of this cubicle, the occupants dug out canals against the wall so that the water would run down behind the zinc and trickle out into the canals along the main corridors.

Perhaps the most unexpected feature in the shelter cubicles is the array of Maltese tiles that line their floors. Unlike the common areas in the shelters, within the cubicles one gets a sense of people trying to create some sense of home. Probably scavenged from nearby bombed houses, these mismatching tiles give each cubicle its own individual character. Laying tiles would also have made it easier to keep cubicles clean than the porous stone floors.

Top: Area in the shelters where there is constant water penetration and the rock is brittle. No attempt was made at digging out cubicles in this part of the shelters;

Top: Area in the shelters where there is constant water penetration and the rock is brittle. No attempt was made at digging out cubicles in this part of the shelters;

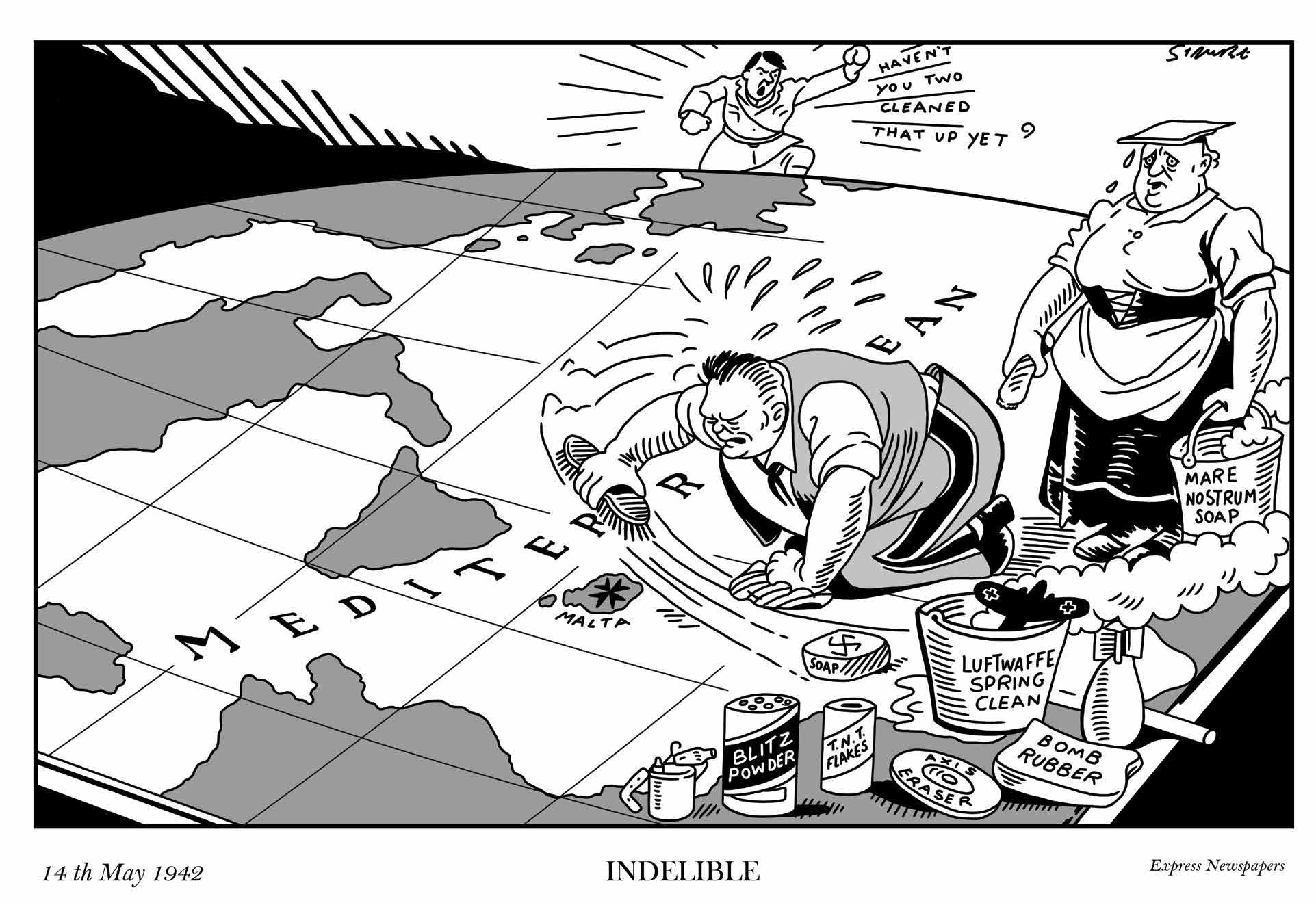

Above: ‘Indelible’ despite Kesselring’s best efforts to ‘wipe her off the map’. A cartoon that appeared in the UK newspaper, Daily Express in May 1942; Opposite: An ambulance overturned in an air raid in Old Bakery Street, Valletta.

In 1941, attacks originating from Malta had begun to seriously hurt the Axis supply lines between Italy and North Africa. By the end of 1941, the Germans decided that they had had enough and were determined to ‘snuff out the hornet’s nest’. The Luftwaffe was put under the command of Air Field Albert Marshall Kesselring whose strategy was to neutralise Malta, bomb it into submission, starve the Islands, and then invade.

Bombs rained down on Malta day and night reaching epic proportions in April 1942. The brave or foolhardy would remain outside the shelters to watch the dramatic fight for the skies as British military planes, which now also included Spitfires, and anti-aircraft guns attempted to bring down the oncoming bombers.

Previous Page: Handsome tiles decorate the floor and a carved-out shelf in this private cubicle.

On 15 February 1942, slightly down the road from the Great Siege Square entrance to the shelters, the Regent Cinema on Republic Street received a direct hit. It was packed for its afternoon show. Lina Ciarlo recalled her narrow escape:

“… we walked back at a leisurely pace, and being in no particular hurry lingered for a while in Kingsway (Republic Street), pausing for some minutes opposite the Regent Cinema, where now stands Regency House. My brother was standing beside the florist’s kiosk, and was preparing to get into the cinema for the five o-clock performance. I asked my father to let me go with my brother, but instead he called my brother and told him to go home with us. Muttering under his breath my brother joined us and we had just taken a few steps in the direction of our home when the deafening sound of gunfire and of aircraft engines shattered the peaceful evening. Everyone ran in the direction of the shelter in Queen Square. Terrified out of my wits I ran with the crowd. Suddenly there was a tremendous explosion, followed by the sound of breaking glass. The Regent Cinema had received a direct hit, and death and destruction lay around. Many were dead and injured and throughout the night and the following day soldiers and policemen strove to save those trapped under the fallen masonry… even now, many years after the event, I can remember every detail.” (Mizzi L. 1998)

By April 1942, Malta had endured 117 consecutive days of unrelenting air raids. During April alone, 6,728 tonnes of bombs were dropped over Malta, surpassing anything London had suffered at the height of its blitz. On 7 April, one of Valletta’s gems, the Royal Opera House was destroyed, along with palaces, shops and homes. Between bombings, people searched the wreckage for victims. Shelters became overcrowded, and damage to the water mains led to a deterioration of sanitary facilities. Reuter’s correspondent W. Beck described how “a pall of dust and smoke hung in the air [over Valletta], impenetrable even by the sun.” (Micallef J. 1984)

Right:

Above: Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, July 1940.

Ration coupon for kerosene in Castille Square, Valletta;

Above: Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, July 1940.

Ration coupon for kerosene in Castille Square, Valletta;

The food situation deteriorated rapidly in 1942. As the Axis powers targeted supply ships trying to reach Malta, the situation became desperate. The Market had been severely damaged in the raids of 7 April, destroying supplies. Grocery shops closed as their shelves were emptied. Places of entertainment closed and bars ran dry. Rations were reduced until people were on the verge of starvation. The shortage of fodder led to most of Malta’s livestock being slaughtered, thus further depleting supplies of meat, eggs and milk. In 1942, the infant mortality rate rose to 345 per thousand. As rations were cut and food became unavailable in shops and more difficult to acquire on the black market, more people were forced to resort to the Victory Kitchens.

The Victory Kitchens were communal kitchens that served one hot meal a day in return for a portion of people’s rations. Initially catering to the poor or homeless, they soon were catering to most of the Island. The first one opened in Lija on 3 January 1942 and then others rapidly sprung up throughout the country. By 31 October 1942, 147,000 people were registered. People complained that the food was often inedible, but had little choice. The menu generally consisted of a watery ‘stew’ with a few vegetables and beans, a piece of tinned fish or an ounce of corned beef, and occasionally goat’s meat.

On the brink of starvation, Malta could not hold out much longer. Infants, the weak and old died in increasing numbers. The Island was also reaching a point where it would be unable to defend itself – its fuel supplies were almost exhausted, meaning that its fighter planes would be grounded. People prayed for a miracle. In August 1942, the Archbishop’s circular ordered a Novena ‘to Our Lady to be said in preparation for the feast of the Assumption of Our Lady so that God the merciful may shorten the time of this scourge and grant us His help’. Young and old were called to prayer. Meanwhile, activity in the Grand Harbour hinted that the authorities were preparing for a major operation.

The miracle arrived on 15 August 1942, the feast day of the Assumption of Our Lady, in the shape of the American oil tanker, the Ohio. The event became popularly known as the arrival of the ‘Convoy of Santa Maria’ – locals had no doubt that their prayers had been heard. People cheered from all around the Grand Harbour as they witnessed the Ohio, barely afloat after days of constant attacks, limping into the harbour with her precious cargo, held afloat by two destroyers.

The rescue of Malta had been code-named Operation Pedestal. The convoy deployed to rescue Malta had set out with 14 merchant vessels, the most important being the Ohio. They were flanked by a heavy escort provided by warships from the Home Fleet. After days of bombing and torpedo attacks, the Ohio and just 4 merchant ships carrying food and essential supplies eventually made it to Malta. The loss of life and ships was appalling. However, they had achieved their objective. Malta could hold out a little longer and resume its attacks on German and Italian supply ships, preventing them from reaching North Africa. The tide changed not just for Malta, but also for the Allies in North Africa.

Re-armed and refuelled, Malta’s defenders now began to exact a high price on its attackers. Air raids by the Axis powers became more sporadic and virtually ceased in 1943. By the end of 1942, several ships

with food had reached Malta and rationing was eased. The digging of shelters became less of a priority and diggers were deployed to new defence duties.

The last air raid alert was on 28 August 1944. In total, Malta experienced 3,340 alerts. The total number of civilian casualties from enemy action between 11 June 1940 and 31 December 1944 was 1,540 killed and 3,780 injured. Considering the ferocity of the bombardments, these figures bear witness to the effectiveness of Malta’s Civil Defence and of the reliability of the rock shelters in protecting human life.

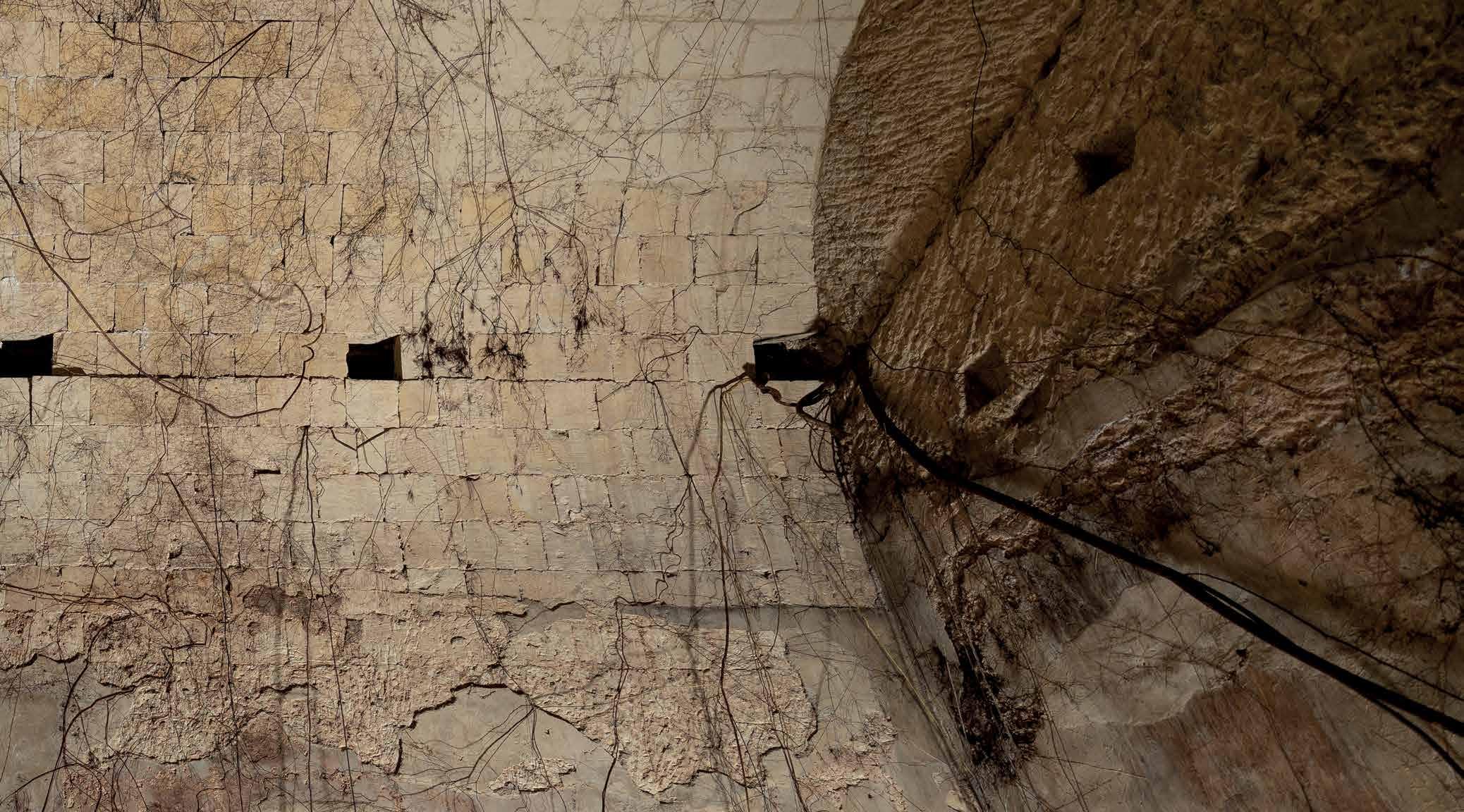

The reservoirs are now alive with straggling roots that find their way into them. Absorbing humidity from these dark underground spaces, the roots nourish the trees that grow in Great Siege Square.

The trees are Ficus microcarpa (ex nitida). Although welcomed for the shade they provide from Malta’s scorching sun, these non-indigenous trees have attracted controversy in recent years. It is argued by some, that trees in Great Siege Square and in St John’s Square, are a colonial intrusion of a British aesthetic that jars with the splendour of the Knight’s architecture. A changing array of trees have definitely been part of the square at least as far back as the early 20th century. The tree roots have also sparked debate on whether they pose a threat to the heritage that lies beneath and around them. Up until now, this has not been found to be the case.

Local environmental NGOs have in turn made an impassioned defence to keep the trees, arguing that they are an Important Bird Area. These trees are the main roosting ground in Malta for a migratory bird, the White Wagtail. Between October and March, often more than 10,000 birds gather in the evening to sleep in these trees.

Above: The migratory bird White wagtail. (Photo: James Aquilina)

Above: The migratory bird White wagtail. (Photo: James Aquilina)

The end of World War II left the Government with the dilemma of what to do with all these shelters. Public shelters in the harbour areas were the last to close since so many residents had lost their homes and needed sheltering until they were re-housed. Shelter hoods over entrances were destroyed and the rubble was often dumped within the shelters themselves. Shelters that had been built at the foot of the bastions, made them more accessible, permitting them to be re-utilised as boat houses, shops and garages. Eventually, the threat of the Cold War led to the rehabilitation of some shelters and even the digging of new underground spaces such as underground flour mills.

The Underground Valletta shelters appear to have remained quite undisturbed after World War II. Some public offices retained access, however, lack of maintenance meant that the shelters were prone to flooding. The first major intervention after the war, in the complex of shelters and water systems that are Underground Valletta, occurred in 1997. During repaving works in Republic Street, workers broke through one of the reservoirs. The Valletta Rehabilitation Project took the opportunity to clean the reservoirs of debris that had been dumped there and created the opening between the Law Courts and Great Siege Square that allows one to enter the reservoir from Republic Street. The metal spiral staircase leads down to the staircase built in 1941. Another modern intervention is the brick column within the larger cistern in front of St John’s. This was built to re-enforce the ceiling during works carried out above.

Valletta 2018, Malta’s turn as the European Capital of Culture, saw a new interest in the reservoirs and shelters. Artists re-imagined the underground spaces, allowing the public to re-encounter these little-known spaces through digital walk-throughs and a sound installation that could be heard from inside the reservoirs.

The Government entrusted custodianship of Underground Valletta to Heritage Malta in 2019. Heritage Malta immediately undertook works to enable the shelters and reservoirs to be opened regularly to visitors. Underground Valletta opened in November 2021. In 2022, Underground Valletta was visited by 5,973 people.

Further research is giving new insights into the development of the City and its underground spaces. This includes archival research, archaeological

studies and employing documentation technologies like photogrammetry and laser scanning. These not only generate new narratives but also enable new methods for presenting the site and making it more accessible.

Underground Valletta in the 21st century

Valletta’s underground still services the City. The 19th-century tunnels still serve their original functions of sewerage and drainage. New trenches carry cables for telephony and electricity. Some old cisterns and reservoirs have been restored so that they can serve their original function as well. Valletta’s underground spaces are also being adapted to new uses, such as art galleries, museums, theatres and restaurants. Converting underground spaces to new uses comes with a host of challenges, such as restoration which is sensitive to their original uses and their histories, as well as solving practical problems like lighting, water drainage and humidity, often require creative solutions.

Underground Valletta aims to enable visitors to look beyond the palaces, churches and monuments, to consider the hidden spaces that allow people to carry out the multitude of activities that one expects in a 21st-century capital that is borne by 500 years of adaptation and invention.

ARP: Air Raid Precautions

PWD: Public Works Department

NMA: National Museum of Archaeology

NWMA: National War Museum Archives (previously National War Museum Association)

WSC: Water Services Corporation

Botte: A liquid measure used by the Knights of St John. The conversion is not straightforward due to botte varying in measure for different liquids. This book adopts the conversion used in The Malta Blue Book 1891 https://nso.gov.mt/wpcontent/uploads/1891_chapterO.pdf (also see Zammit 2022: 212).

Cistern: A method of water harvesting by channeling rainwater into watertight chambers. In Valletta, these were rock-cut chambers that were made waterproof with mortar. The main type of domestic cistern in Valletta

Published Sources

was bell-shaped. Bell-shaped cisterns were accessed through a small opening at the surface.

Falsework:Temporary framework structures used to support a building during its construction.

Reservoir/ tank: Refer to very large cisterns. In Valletta, they were generally state-managed in order to manage the water supply. These were normally built in a cuboid shape and roofed by bricks. They were initially built to harvest rainwater, but after 1615, were also topped up by water from the aqueduct.

BLOUET, B. 1964. ‘Town Planning in Malta, 1530-1798’ in The Town Planning Review, Oct 1964, Vol.35, No. 3, pp 183-194. Liverpool University Press.

BONELLO, G. 2022. ‘Bontadino de Bontadini’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

BORG, M. 2001. British Colonial Architecture: Malta 1800–1900. PEG.

BUTTIGIEG, E. 2018. ‘Early Modern Valletta: Beyond the Renaissance City’ in Abdilla-Cunningham, M, Camilleri M. & Vella G. Humillima Civitas Vallettae: From Mount Xeb-er-ras to European Capital of Culture Heritage Malta; Malta Libraries.

CASSAR, C. 2000. Society, Culture and Identity in Early Modern Malta. Mireva Publications.

CASSAR, P. 1965. Medical History of Malta. Wellcome Historical Medical Library.

CHADWICK, O. 1896. Report on the Sewerage of Malta with Estimates. Government Printing Office.

CILIA, D., GRIMA. R. 2008. The Making of Malta. Midsea Books.

CILIA, D. 2022. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

DE GIORGIO, R. 1985. A City By An Order. Progress Press.

DE LUCCA, D. 1999. Carapecchia – Master of Baroque Architecture in Early Eighteenth Century Malta. Midsea Books.

DEBATTISTA, M.G. 2022. The Front Page on the Front Line: The Maltese Newspapers and the Second World War Midsea Books.

GALEA, F.R. 2006. Women of Malta – True wartime stories of Christina Ratcliffe and Tamara Marks. Wise Owl Publication.

GANADO, A. 2018. Malta in World War II – Wartime Drawings by Alfred Gerada (1895 – 1968). Midsea Books.

HARRISON, A. & HUBBARD, A. 1945. A Report to Accompany the Outline Plan for the Region of Valletta and the Three Cities. The Government of Malta.

HOLLAND, J. 2003. Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege, 1940-1943. Orion Publishing Group.

NATIONAL STATISTICS OFFICE 1891. Malta Blue Book. https://nso.gov.mt/wp-content/uploads/1891_ chapterO.pdf

MICALLEF, J. 1981. When Malta Stood Alone. Malta.

MALLIA-MILANES, V. n.d. Valletta 1566-1798 An Epitome of Europe. JP Advertising.

MIZZI, J. (ed). Malta at War. (journal). Bieb Bieb.

MIZZI, L. 1998. The People’s War: 1940-1943. (trans. By Joseph. M Falzon). Progress Press.

PEDLEY, M, HUGHES-CLARKE & GALEA, P. 2002. Limestone Isles in a Crystal Sea – The Geology of the Maltese Islands. PEG.

PERESSO, V. 2020. Fountain in Front of Courts in Valletta on https://www.facebook.com/search/ top?q=courts%20fountain%20valletta

RESTALL, B. ‘Water Supply during British Rule’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

SAID, E. 2005. Subterranean Valletta: A Historical and Descriptive Analysis. (Unpublished Thesis).

SAPIANO, M. 2022. ‘Groundwater development in the Maltese Islands’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

SCHEMBRI, J.A. & SPITERI, S.C. 2019. ‘By gentlemen for gentlemen - ria coastal landforms and the fortified imprints of Valletta and its harbours’ in Landscapes and Landforms of the Maltese Islands Springer.

SPITERI, M. 2021. The Houses of Baroque Valletta 1650–1750 – Property redevelopment from records of the Officio delle Case: socio-economic reflections on civil buildings. Midsea Books.

SPITERI, S. C. 1994. Fortresses of the Cross – Hospitalier Military Architecture (1136-1798). A Heritage Interpretation Services Publication.

SPITERI, S. C. 2022. ‘Water and Hospitaller Fortifications’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

VELLA, C. 2022. The Sanitary Infrastructure of the Maltese Islands, 1850s – 1930s. (Unpublished Thesis).

VELLA, P. 1985. Malta Blitzed but not Beaten

VELLA, T. 2022. ‘Fountains in Valletta’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability Water Services Corporation.

VELLA BONAVITA, R. 2018. ‘Francesco Laparelli’s Vision for The New City on Mount Xiberras February 1566’ in Abdilla-Cunningham, M, Camilleri M. & Vella G. Humillima Civitas Vallettae: From Mount Xeber-ras to European Capital of Culture. Heritage Malta; Malta Libraries.

ZAMMIT, V. 2022. ‘Cisterne e Gebbie Pubbliche e Private’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

ZARB-DIMECH, A. 2003. Mobilization in Action – A History of Civil Defence in Malta 1940-1943. Malta.

ZARB-DIMECH, A. 2001. Taking Cover – A history of air-raid shelters Malta: 1940-1943. Malta.

ZERAFA, S. 2022. ‘More than a Simple Flush’ in Cilia, D. 8,000 Years of Water – A Maltese History of Sustainability. Water Services Corporation.

Unpublished Sources

ELLUL, M. 1984. Tunnels and Underground Passages in Valletta. National Archives of Malta, Box 1.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA - Series PDE 026, Registry No. Lorenzo Gatt. Series 009 – Reports and Speeches.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA - Series PDE 026, Registry No. Lorenzo Gatt. Series 010 – Works and Projects, Item 001, Drainage Works.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA – Public Works File: Sea Water Fountain in Front of the Law Courts.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MALTA - Series PDE 026, Registry No. Lorenzo Gatt. Series 009 – Reports and Speeches, Item 004, Proposal for Anti-Raid Services.

NATIONAL WAR MUSEUM ARCHIVES - Shelter Files.

Plans and Diagrams

Pg 32: PWD. Plans and Sections of the Public Tanks and Cisterns in Valletta District. 1847; Pg 33: PWD Roll 47/ 19; Pg 35: PWD, now at WSC - Plan 35. Pg 36-37: Roll 19A/28B ; Pg 38: Roll 19A/24; Pg 40: Roll 47; Pg 47: Valletta Shelters No. 25; Pg 48: 132A/64A; Pg73: NMA M1410/17.

Tours to Underground Valletta currently depart from the National Museum of Archaeology in Republic Street, Valletta. For the latest information on visiting Underground Valletta, visit the Heritage Malta website www.heritagemalta.org

Walk

Tours depart from the National Museum of Archaeology in Republic Street. Both the museum and Underground Valletta are situated in the City centre which is a pedestrian zone. They are around three minutes apart on foot. Valletta is approximately one and a half kilometres in length, making everywhere quite reachable. However, bear in mind the steep steps and slopes you will find outside the City centre.

Bus

Buses arrive at the bus terminus right outside Valletta City Gate. A bridge leads into Valletta’s City centre via Republic Street. The National Museum of Archaeology is around five minutes on foot from the bus terminus.

Ferry

There are three ferry services to Valletta:

- from The Strand, Sliema to Marsamxett Harbour.

- from Bormla, Dock 1 to Xatt Lascaris (Grand Harbour side)

- from Mġarr, Gozo to Xatt Lascaris (Grand Harbour side)

On the Grand Harbour side, you can take an elevator into the City centre. Should you want to navigate Valletta’s stairs and hills, you can enter the City through Victoria Gate. On arriving on the Marsamxett side, you can get to the centre by walking up St Mark Street and Melita Street.

Valletta has a Controlled Vehicular Access (CVA) system in place. You can view tariffs on https://secure.cva.gov.mt/Page/Tariffs . Public car spaces are marked in white, blue and green. You can park in white spaces at all times and in blue spaces between 7:00am to 7:00pm. After 7:00pm blue spaces are reserved for residents. Green spaces are solely for residents at all times. On weekdays, parking tends to get taken up early by daily commuters.

Taxi

Taxis can drop you off around a minute’s walk away from the National Museum of Archaeology.

The site and amenities

Underground Valletta is a system of dark corridors of around a metre and a half in width. There are flights of steps to enter and exit the site. Some areas are muddy and quite slippery. One needs to wear sturdy, closed shoes to enter the site, and to be sure-footed.

There are no restrooms available in Underground Valletta.

There is no Wi-Fi in Underground Valletta. At the National Museum of Archaeology, you will find lockers where you can leave your belongings. You can use the Museum’s restrooms and use the Museum’s free Wi-Fi

A Heritage Malta shop at the National Museum of Archaeology gives visitors the opportunity to purchase unique items inspired by Malta’s heritage. These items range from mementos to scholarly books. Heritage Malta members enjoy a discount on purchased items.

While walking through the City, various gutters, drains and man-holes are the only hint of the vast complex of tunnels that lie beneath Valletta’s streets. As everyday business goes on, the dark silent spaces below, long abandoned as the needs of the City has moved on, are imbued with telltale signs of those who sought refuge within them during the bombings of World War II.