9 minute read

Written in stone

WORDS: NICOLA MARTIN • IMAGERY: ALAN DOVE

Lost knowledge is threatening the retention and conservation of New Zealand heritage structures built using lime and stone – but moves are afoot to help retrieve it

If the walls could talk in some of New Zealand’s oldest stone buildings, they would speak to changing construction practices dating back to World War II and skills lost between generations. As Australian heritage consultant David Young acknowledges, there’s no escaping the anthropomorphic nature of stone walls. They may not actually talk, but they certainly breathe.

“There’s a fundamental understanding that air gets inside limestone, and bricks and lime mortar, and that walls exchange that air with the atmosphere – that walls breathe,” he says.

Among the many hats he wears, David is involved in the Building Limes Forum (BLF) – an international organisation with many independent branches around the world – which encourages expertise and understanding in the appropriate use of building limes.

A New Zealand chapter of the forum was set up late last year and is co-chaired by Dunedin stonemason and Heritage New Zealand Conservation Advisor Otago/Southland Andrew Barsby. Andrew returned from Melbourne over a year ago to take up his new role and discovered, as time has moved on and building techniques have changed, that generations of knowledge have been lost in New Zealand’s stone conservation history.

“There are so many at-risk heritage buildings in New Zealand that are just hanging on. Another 50 years of people doing nothing to maintain them – or the wrong things – will lead to demolition by neglect, or at least the loss of the very surface of these buildings,” says Andrew.

Part of the plan proposed to increase knowledge and skills in this area, says Andrew, is for the New Zealand BLF to run a workshop focused on how to work with lime and stone.

David says the knowledge gap in methods and materials comes from dramatic changes in building practice from World War II and more recently, as new building techniques and materials have developed.

Modern cement, acrylic paints and even changes in building codes, designed with safety in mind, have all taken their toll on our stone buildings.

“Materials like acrylic paints don’t breathe enough. You end up trapping moisture behind the paint. The traditional coatings were usually lime washes, sometimes with added extras to weatherproof them, like tallow or linseed oil,” says David.

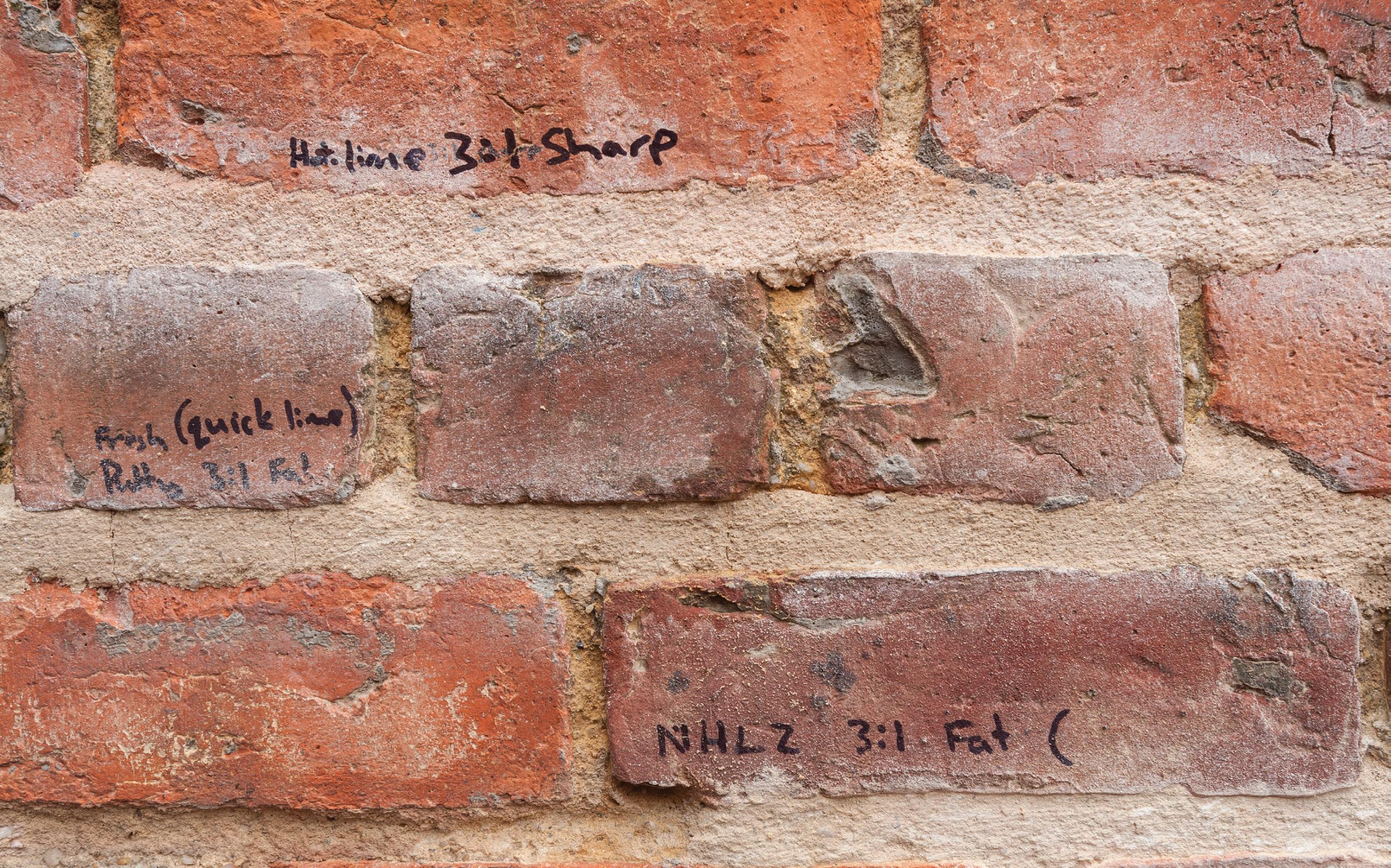

2 Different lime plasters, with dates recorded, which can be used in projects. Salt damage and seepage are two of the consequences of maintaining lime and stone build- ings incorrectly.

3 Stonemason Stuart Griffiths (left) and Andrew Barsby experi- ment with lime solutions.

4 A build-up of salt crystals can eventually blow the stone apart.

“The contemporary use of cement in reinforced concrete is great, but using it in mortars, which has become the norm, is not right for use with softer porous materials like limestone.” When stone buildings are not allowed to breathe, moisture becomes trapped, leading to damp masonry and buildings that are bad for people’s health or are simply not energy efficient.

In the worst-case scenario, rising damp that becomes trapped within cement or behind acrylic paints can lead to salt crystals being deposited within the stone.

A build-up of these crystals can eventually blow the stone apart, causing expensive and sometimes irreparable damage.

For building owners, says David, maintenance can be a costly and difficult exercise, but while it may be expensive to do it right, doing it wrong can cost far more.

Andrew says that while building owners can’t be forced to perform maintenance, doing small amounts at a time can save dollars later down the track.

3

She has owned her stone cottage in Lawrence, on the edge of Central Otago, for six years and has been chipping away at its restoration.

Her cottage was built in 1860 using clay mortar and finished with a lime plaster. “The building techniques today, they want to seal everything up, but lime needs to breathe and have airflow.

“We’ve found it hard to find builders who will embrace that knowledge and find the products that they can use to do the work.” Jenny says she has learned a lot about rising damp and the next challenge is to tackle the exterior paint on the cottage. “The maintenance on them [these types of home] is so important,” she says.

Another Dunedinite with a passion for stone buildings, and who is also involved in the New Zealand BLF chapter, is stonemason Stuart Griffiths. Stuart is working alongside the Dunedin City Council on the Hereweka Harbour Cone Trust project, which includes the restoration of three lime kilns at the historic McDonald’s Lime quarry on the Otago Peninsula. Stuart has a passion for stone that stretches across decades. He is a founding member of Dunedin’s Long Beach Masons, who were responsible for stonework including the entrance to Dunedin’s Botanic Garden, the stone arch in the duck pond, and the Kokonga Basalt stone around the herb gardens.

A member of Stuart’s cohort, Paul Cahill, was also involved in armouring the roadside along Dunedin’s harbour with bluestone, currently one of the largest stone projects in the world.

Stuart believes that things like the continuity of work (there aren’t many projects in New Zealand), new off-the-shelf materials, economics and the necessary building codes and policies are all hindering a thriving stone culture in New Zealand.

Accessing quarries or finding the original quarries in which stone has been extracted also poses difficulties in restoration projects, he says.

In many cases, stonemasons are using imported lime bought off the shelf. The methods used

are still quality stonemasonry, but they are eroding another opportunity to use traditional quarrying techniques, he says. Those in the Hereweka Harbour Cone Trust project are working with a doctoral student to identify the origin of the lime for the kilns and subsequently develop a method that other projects can use in restorations. Stuart’s first job as a stonemason was building a house in Arrowtown in the 1980s using chlorite schist quarried from the property. An older stonemason in charge of the job left after a week because of the sheer scale of the work.

“He left two young guys standing there looking at each other and thinking we’d better have a look around for some more experience.

There are now new pockets of encouragement, he says, including the proposed workshop.

He says many stonemasons are also coming here from Britain to work on projects, so hopefully there will be the continuity of work there to grow the skill base. He believes those walking past these stone buildings every day would never notice many of the methods employed to ensure new earthquake standards, for example, are met.

Many stonemasons are now creating stone veneers or tiles, where once they would have cut full blocks of stone, and this can create tensions on projects where old and new building techniques are employed together.

Stuart says there is an ongoing conversation about how heritage stone buildings are being preserved, which includes the question of whether new work should be visible in order to denote the journey between old

2

3 Jenny McKerrow has struggled to find knowledge about working with lime in New Zealand as she restores her stone cottage in Central Otago. Stuart Griffiths’ work has included constructing the entrance to Dunedin’s Botanic Garden.

One of the three lime kilns being restored at the historic McDonald’s Lime quarry on the Otago Peninsula.

and new, or whether visitors and viewers should be allowed a seamless experience.

“Being a professional stonemason, I always look for good practice and I think people should come across these structures as if they have been uninterrupted by the visible hand,” he says.

He points to Dunedin’s Standard Building as a good example. Owner Ted Daniels had the façade restored to its former glory before renovating the inside in a contemporary fashion.

On the face of it, he says, it looks like a 19th-century building, but as you walk through the door you enter a very modern building with significant heritage elements that have been carefully retained, built in this century with great skill, quality materials and craftmanship.

A similar conversation is happening on the Hereweka Harbour Cone Trust project: whether to completely restore the historic kilns or simply reinforce them to allow public access. Whether lime from the site is used is also being discussed.

It’s an interesting conversation, says Stuart, but ultimately the preservation and conservation of New Zealand’s stone buildings are at the forefront.

As Heritage New Zealand’s Andrew Barsby says, these buildings are our heritage and our stories, and they are as much about people as about the buildings themselves.

RETURN TO CONTENTS

2

WORDS AND IMAGE: ROB SUISTED

Strategic spectacle

I’ve been interested in the sites of the New Zealand and Waikato Wars since writing a small heritage book a few years ago. I was travelling to the New Zealand Photographer of the Year awards in Auckland and had a few spare days in which to ramble around on my motorbike and find fresh imagery. I’d ridden around Raglan Harbour and up to Port Waikato, heading for Auckland as the sun slowly set. Passing under Alexandra Redoubt, I knew the low angle of the sun would pop the earthworks into relief, essential to show the construction. I arrived, quickly sent my drone skyward and got one set of images spotlighting the high ground before the sun disappeared into cloud. That spotlight effect created a striking image and showed clearly why this was such a strategic Waikato location for the redoubt. Four frames were shot and combined to get the sweeping panoramic view. Oh, and I did okay in the awards too.

TECHNICAL DATA Location: Alexandra Redoubt, built in 1863 by the 65th Regiment, led by Colonel Alfred Wyatt, above the Waikato River at Tuakau. Aerial view at sunset, Tuakau, Franklin District, New Zealand.