8 minute read

SOUNDS FAMILIAR

WORDS: GARETH SHUTE / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

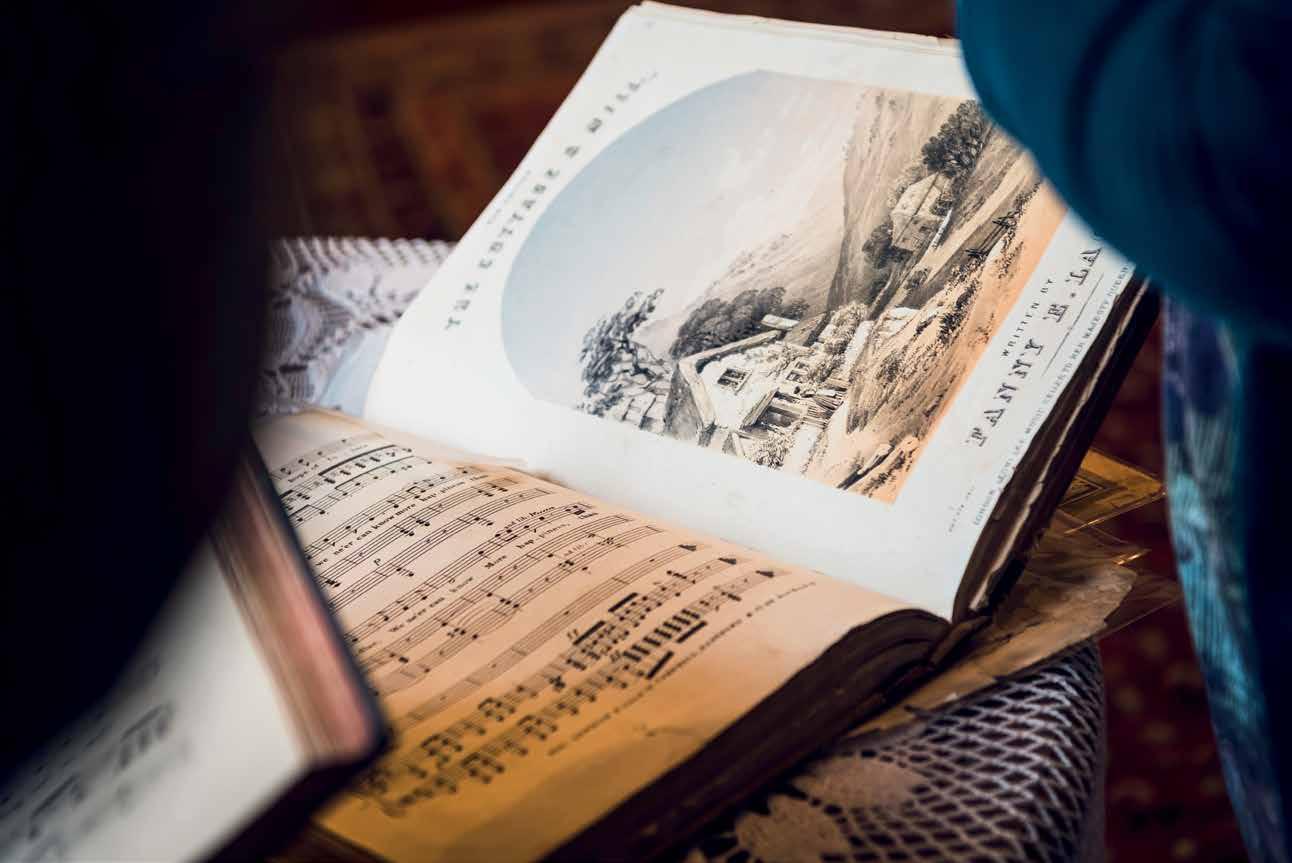

Sheet music belonging to the former inhabitants of historic homes sheds light on their lives - and the musical tastes of the times

Pianos take pride of place in many historic homes, embodying a time when former residents would gather around them to sing, or watch the best pianist in the house perform.

In larger homes there could even be more than one; Auckland’s Alberton, for example, has one in its ballroom and another in the drawing room (although the instrument in the latter is not playable).

But it is the sheet music these residents owned that perhaps provides more of an insight into the role that music played in their lives. These tunes, after all, can still be played, and their scores offer clues to how they were obtained and used.

Many properties cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga have their own collections of sheet music, including the three historic Auckland homes of Alberton, Highwic and Ewelme.

Dr Elizabeth Nichol, who catalogued the collections at the three properties – having written her PhD on New Zealand sheet music from 1850 to 1913 and drawing on knowledge from her years as a librarian –saw many reminders of the central role that pianos played in the lives of early European immigrants, such as the Lush family, who lived at Ewelme.

“There is a comment in [Revd] Vicesimus Lush’s diary in 1852, saying how excited he was that the piano had arrived and would soon be in their house,” she says.

“You can also see that music was important for the Kerr Taylors, who lived at Alberton, because they had sheet music that they had brought with them from England, which is clear from the dates or places of purchase printed on the volumes.”

In those days the only way to listen to music at home was when it was performed, so pianos played the role of the modern stereo. The central city felt more distant in an era when most people travelled by foot, so local halls held regular events that drew on the talents of those in the neighbourhood. It was only by practising with sheet music at home that budding musicians could become involved, Elizabeth explains.

“There were lots of benefit concerts and concerts organised by amateur clubs and associations, and the Kerr Taylor daughters performed in some of those. There are also vocal scores in the [Kerr Taylor] collection from when the girls sang in the local St Luke’s choir and the Auckland Diocesan Choral Association festivals.

“The Lush’s piano in their home at Ewelme was also used by members of the family who played the organ at the church. This is reflected in pieces of church music and music for the harmonium.”

The Ewelme collection also contains some violin music, as Revd Lush’s granddaughter studied it in London, returning to teach it in the 1920s and ’30s. Sheet music was largely imported from overseas, although local publishers, such as the Dunedin firm Beggs, began producing works from the 1860s.

In the Highwic collection, there are two locally printed copies of ‘Long It Is, Love, Since We Parted’ by Australian composer and performer David Cope, which was released to coincide with his 1870-80s tours (they are the only copies of this edition known to exist, according to Elizabeth). The Ewelme collection holds the earliest New Zealand-printed piece (1862) that Elizabeth could find: ‘Fairy Bells: Polka Mazurka’ was clearly a personal copy since it had ‘BH [Blanche Hawkins] Lush’ written in pencil at the top.

Some scores in the Alberton collection were torn from magazines, such as The Lady’s Companion and The New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal , and from newspapers (usually from the ‘Ladies’ pages). Elizabeth found that she could tell which songs the families liked the most because the pages had been repaired (with brown paper tape, for example) or still showed fingermarks on the corners.

In order to keep their collections in good shape, families sometimes arranged for bookbinders to combine loose sheets into single, bound volumes.

There are few New Zealand compositions in the sheet music collections in the three houses, but they provide some fascinating links to the wider history of local music; for example, there are some early pieces by internationally successful New ZealandAustralian composer Alfred Hill.

In other cases, more tangential threads tying the past to the present can be found. There is a composition (‘The Countess Waltz’) by child prodigy pianist Clarice Brabazon, which was published in The New Zealand Graphic in 1903. Clarice later married renowned singer Horace Stebbing, who was the uncle of Eldred Stebbing –the founder of Stebbing Recording Studio, which is still operating on Auckland’s Jervois Road.

Local compositions were often written for specific purposes, Elizabeth explains.

“A piece might be written for a particular occasion, so a publisher could put it in the shop window and hope to sell a few in that short period of time, for example if the Governor-General was visiting, or as a way to support our troops fighting in the Boer War.”

Compositions might also be written to raise the profile of the composers, such as when music retailer and teacher WH Webbe wrote a piece named after his daughter Madoleine (also a teacher at his music school). A copy of this piece is still at Alberton.

The existence of these collections begs the question: could this same music be played once more in these historic homes? The locations have certainly been used by musicians in more recent times. Highwic’s interior has been used for music videos such as Troy Kingi’s ‘First Take Strut’, and its grounds have hosted a garden party featuring a harpist, cellist and roving carol singer.

There has even been a performance by string quartet The Whistledowns, featuring a selection of modern songs rewritten in an historical style from the TV show Bridgerton Alberton has seen similar small ensembles play, and has also hosted music video shoots, such as for ‘You’ by Hollie Smith, featuring the NZSO.

The question also played a part in a recent internship undertaken at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, which investigated how the sheet music might be used to plan a concert. Tessa Dalgety-Evans, then a University of Otago student (and now working as a learning facilitator at the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa), undertook the research, with her background as a musician (cellist) also helping.

“The music I was seeing at Alberton was classical and popular salon music from the early 1900s or even late 1800s,” says Tessa.

“For example, there was ‘Ta-ra-ra-Boomde-ay’, which was used in the kids’ TV show Barney in the early 2000s but harks back to that salon era. It would be great to do a new arrangement of a piece like that, or even some of the very early jazz in the collections, which could possibly allow improvisation.”

Tessa acknowledges that some of the light romantic songs popular in the 1800s might sound treacly to modern ears. However, she made a playlist of those recordings she could find, and she believes a good arranger could update them for a modern audience. She also began transcribing sheet music in the collection onto digital software (MuseScore) to make it more accessible.

Tessa did find a small number of songs that would now be inappropriate to play. For example, some are written in a mock-AfricanAmerican vernacular that would be culturally offensive to modern listeners.

Nonetheless, she believes there is plenty of worthwhile material to underpin a stripped-back performance in the style of NPR Music’s ‘Tiny Desk Concerts’. This suggestion is echoed by Elizabeth, who has heard of ‘living museums’ where performers were hired to play in historic homes, even if just practising a piece as the original inhabitants would have done. (She notes, however, that the concept sometimes confused visitors, who were reluctant to enter and disturb the musicians.) Elizabeth agrees that the collections hold some hidden gems that could be brought back to life if treated in the right way.

“It is really hard to get in the right headspace to listen to some of this light music from 150 years ago. It is a pity they’re all tarred with the same brush. Some of them don’t show much originality or musical skill; however, others are quite lovely, and it is a bit sad that those ones are lost to modern listeners.”

To hear more from Elizabeth (and Ruth playing), view our video story here: youtube.com/ HeritageNewZealand PouhereTaonga