11 minute read

A comparison between Urgency Related Groups and the Australian Emergency Care Classification // Clare Searson, Laura Harris

from HIM-Interchange

by HIMAA.org.au

A comparison between Urgency Related Groups and the Australian Emergency Care Classification

Clare Searson and Laura Harris

Advertisement

Introduction Emergency departments are dedicated hospital-based facilities specifically designed and staffed to provide 24-hour emergency care. The role of the emergency department is to diagnose and treat acute and urgent illnesses and injuries (Independent Hospital Pricing Authority [IHPA] 2019a). Annually, there is an increasing demand on emergency departments in Australian public hospitals. The average emergency department presentation growth from 2013-14 to 2017-18 was 2.7% per annum, which surpasses the average growth of the population over the same period. Total emergency department presentations have increased 11% over the past 5 years, and in the 2017-18 financial year presentations exceeded 8 million (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2018a, p.4).

Consequently, national emergency department expenditure is increasing year on year. Due to an 8% increase from the previous year, the 2016-17 financial year expenditure exceeded $5 billion (IHPA 2019b, p13). While this increase in expenditure may be associated with improved costing processes in public hospitals, the trend correlates with the increased number of presentations and therefore resource utilisation required for service delivery. Due to an ageing population, increasing life expectancy and prevalence of chronic and complex diseases (AIHW 2018b) the number of presentations and therefore demand on Australian emergency departments will continue to rise. To ensure optimal resources are available for emergency department care delivery, the development of a new emergency care classification, which better accounts for patient complexity and cost variation, is required.

Currently, IHPA classifies care provided by emergency departments utilising the Urgency Related Groups (URG) system. The care provided by emergency services are classified according to the Urgency Disposition Groups (UDG) system (IHPA 2019c). For example, an emergency service in a small rural hospital staffed with an on-call visiting medical officer would classify patient activity utilising the UDG system rather than the URG system, due to limitations in data collection at smaller hospitals. The URG and UDG systems were adopted as an interim measure to classify emergency care for the purpose of activity-based funding (ABF), which was nationally implemented in July 2012. “ Due to an ageing population, increasing life expectancy and prevalence of chronic and complex diseases the number of presentations and therefore demand on Australian emergency departments will continue to rise.

”

In 2013 IHPA commissioned an investigative review, conducted by Health Policy Analysis, to determine whether current systems appropriately classified emergency care and whether more suitable classifications were available. The review determined that current classification systems were not appropriate for ABF on a long term basis. This was due to the reliance on triage category as a proxy measure for patient complexity, restricted capacity for classification refinements, and limited clinical meaning (Health Policy Analysis 2014). The review explored alternative national and international emergency care classifications for use

in Australia. However, none were deemed appropriate. The review concluded that development of a new national emergency care classification would overcome current system limitations and provide more accurate data on clinical profiles, cost variation and resource utilisation for ABF purposes.

The following fictional case study will be referred to throughout the article: Case Study Name: Albert Simms Age: 86 Place of residence: Holbean Residential Aged Care Facility Transport mode of arrival: Ambulance Triage category: Level 2 Symptoms: Blood tinged mucus Chest pain worsens when coughing Fever 39.8 Emergency department principal diagnosis: Pneumonia, bacterial (75570004 or J15.9) Episode end status: Admitted to hospital

Emergency care classification development comparison The URG system was developed using data from a Western Australia based study from three teaching hospital emergency departments (Jelinek 1992). IHPA adopted and modified the original URG system prior to its implementation for ABF, in order to meet national requirements. To ensure the URG system was meeting the demands of emergency care in Australia, the classification underwent several refinements. However, further improvements to the URG system would have required major structural changes to the classification.

IHPA commenced classification development on a new Australian Emergency Care Classification (AECC) to replace the URG system in 2013. The AECC development stages included: • An investigative review of national and international classification systems for emergency care (Health Policy Analysis 2014) • Analysis of data from national activity and cost data collections to inform determination of cost drivers for emergency care

• A national emergency department costing study and clinician time consensus study in 2016 to facilitate indepth data analysis of emergency department patient characteristics and costs • Development of a classification tree and draft classification structure • Public consultation on the draft AECC

• Release of the classification for review by IHPA’s stakeholders, committees and health ministers.

The systematic development process of the AECC facilitated increased data analysis and significant stakeholder engagement, which resulted in a robust, dynamic and clinically relevant classification which has several structural differences compared to the URG system.

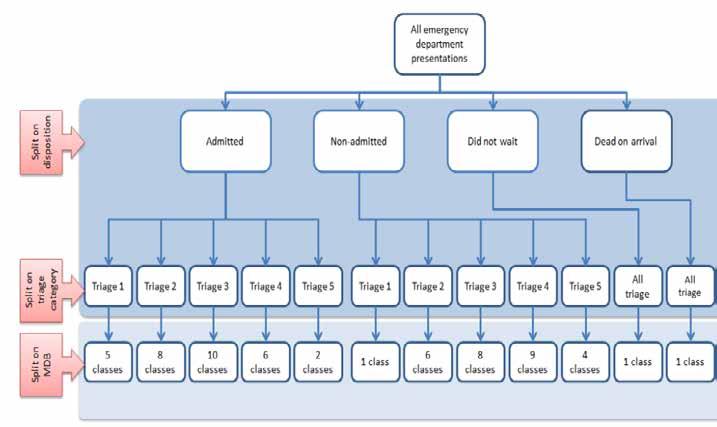

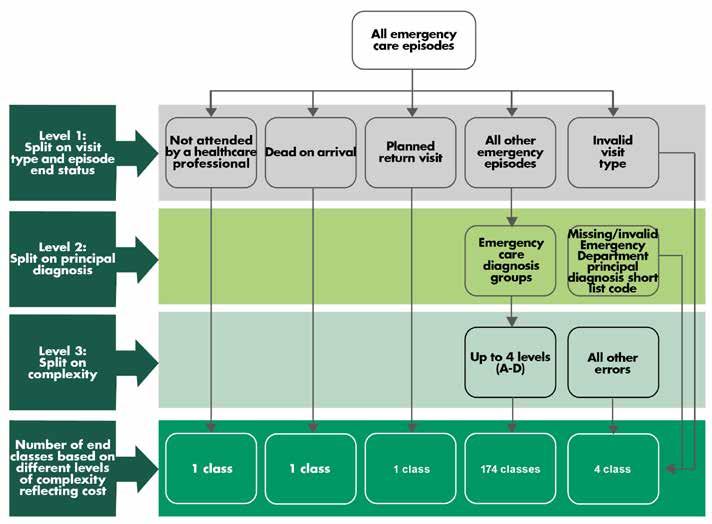

AECC and URG comparison Structurally, the URG and AECC systems both have a three level hierarchical classification structure. Figure 1 and Figure 2 reflect how the classifications sort emergency department episodes into different end classes.

Figure 2: AECC Classification Structure

The AECC and URG system both utilise variables that are currently available in national datasets. The difference between the classifications are demonstrated through the structure and utilisation of those variables, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Classification hierarchy and variables utilised by URGs and the AECC

LEVEL 1

LEVEL 2

LEVEL 3 URGs V1.4 Episode end status (e.g. admitted to this hospital) Triage (e.g. 1 – resuscitation, 2 – emergency, 3 – urgent, 4 – semi urgent, 5 – non urgent) Major diagnostic block (e.g principal diagnosis) AECC V1.0 Type of visit (e.g. emergency presentation) or episode end status

Principal diagnosis (e.g. J18.9 pneumonia, unspecified)

Complexity, using the following variables: Transport mode of arrival (e.g. ambulance, police/ correctional services vehicle, other), Age (e.g. 0-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-56, 70-74, 75-79, 80-84) Triage Principal diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia subcategory) Episode end status

The main variables utilised by URGs include episode end status (the patient’s discharge destination at the conclusion of the emergency department stay, for example, admitted to hospital or discharged home), triage category and major diagnostic block (MDB). Whereas the AECC incorporates more specific categorisation of principal diagnosis along with patient complexity factors. The AECC classification structure and utilisation of variables has improved clinical relevance, reduced reliance on triage and better represents patient-based factors through greater use of diagnosis or presenting symptoms compared to the URG system.

The first split for both the AECC and URGs is on the visit type or episode end status variables. In the AECC, some episodes are grouped to end classes at the first level and not further split based on diagnosis or complexity. These reflect circumstances such as where the patient did not wait for treatment, was dead on arrival or returned for a pre-planned visit. A diagnosis may not be available or relevant and these episodes account for a small proportion of all emergency department presentations. The majority of episodes for the AECC fall into the ‘all other emergency episodes’ category, which are further split into diagnosis categories, and in some cases complexity levels.

Comparatively, all episodes within the URG system are grouped at the first level using episode end status. The URG system also has some end classes at the first level which are not split any further, for example, for dead on arrival or did not wait cases. The remainder of episodes are grouped into either admitted or non-admitted categories and then further split based on triage category and then MDB.

The second level splitting variables differ for both classifications. The AECC second level groups by principal diagnosis, followed by a third split on complexity, whereas the URG groups at the second level through triage category, followed by a third split based on diagnosis through the MDB.

Diagnosis The second level split for the AECC groups episodes into clinically meaningful diagnosis categories called Emergency Care Diagnosis Groups (ECDGs). ECDGs have subcategories that provide more specificity of diagnosis. ECDGs also have higher level groupings called Emergency Care Categories (ECCs), which are largely based on body system or aetiology. Applying the case study example, the ECC is respiratory, the ECDG is lower respiratory tract infection and the ECDG subcategory is pneumonia. ECDGs are based on IHPA’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD10-AM) emergency department principal diagnosis short list codes (Health Policy Analysis 2019).

The diagnosis variable for the URG system is based on broad diagnosis categories of body systems or specialties, known as MDBs. These MDBs are more general in medical terms in comparison to the AECC ECDGs, which group episodes into major clinical conditions.

Due to the greater specificity of ECDGs, ECDG subcategories and grouping at a higher level of ECCs, these variables can be mapped and analysed to provide more clinically meaningful information on the conditions

with which patients present to emergency departments and enhances the use of data for secondary purposes such as research or health service management.

Table 2 reflects a comparison of the patient journey across both classifications with reference to the case study. Table 2: Components of URGs and the AECC

Components derived from ED principal diagnosis

End classes URGs V1.4

Major Diagnostic Blocks (MDB) (e.g. respiratory system illness, or neurological illness)

Urgency Related Groups (URG) Error end classes 28 AECC V1.0

Emergency Care Category (e.g. E04 Respiratory) Emergency Care Diagnosis (e.g. E0450 Lower Respiratory tract infections) Emergency Care Diagnosis subcategories (e.g. E0451 Pneumonia subcategory) 24

69

132

114 AECC end classes (e.g. E0450B) 177

8 Error end classes 4

Complexity

The third level split for the AECC involves grouping the ECDGs into end classes based on different levels of complexity, reflecting cost. The complexity splits are based on a score assigned to each episode, which is calculated using variables such as age, transport mode of arrival, emergency department principal diagnosis (based on ECDG subcategory), triage category and episode end status.

Comparatively, the complexity variable for the URG system is based on triage category, grouping patients from the first split into one of five triage categories depending on a patients need for medical or nursing care in an emergency department (triage categories are listed in Table 1).

The AECC structure allows for inclusion of improved measures of complexity as additional variables become available (Health Policy Analysis 2019). Incorporating complexity through patient-based variables has been a key achievement of the AECC. The complexity split of the AECC has significantly improved upon limitations of the URG system through reducing reliance on triage and application of complexity levels based on patient factors, such as diagnosis and age.

”

End classes and numbering convention The number of end classes for the URG system is 122, whereas the number of end classes for the AECC has increased to 181. The increased number of end classes in the AECC supports more accurate funding and in depth analysis through further categorisation of data.

The URG numbering convention is simply a numerical list, represented by a number 1 to 128. The numbers do not identify the placement or relationship between end classes in the classification structure.

The numbering convention for the AECC is an alphanumerical code, comprised of three components as shown in Figure 3 (Health Policy Analysis 2019). Each AECC end class has the prefix of ‘E’ to identify the end class as belonging to the emergency care classification. There are three numerical components that represent the ECC, the ECDG and the complexity level.

The AECC numbering convention conveys information on the placement of the end class within the classification hierarchy, whereas the URG numbering convention provides limited clinical meaning through a numerical value.

Figure 3: AECC numbering convention

The increasing number of emergency department presentations, escalating expenditure, increasing pressure of an ageing population and prevalence of chronic, complex conditions compounds the demand placed on emergency departments. The underperformance of URGs is exacerbated by the reliance on triage category as a proxy measure of patient complexity, restricted capacity for classification refinements, and limited clinical meaning. The AECC more appropriately classifies patients in the current emergency department environment of increasing clinical complexity, increasing costs and presentations. The AECC has increased clinical relevance, and enables greater understanding of patient complexity and resource utilisation. The AECC has been developed to allow for future refinement and improvement and has utility beyond funding including health service management, epidemiology, research and service planning. References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018a) Emergency department care 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics. Health services series no. 89. Cat. no. HSE 216. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018b) Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16.AUS 221. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Health Policy Analysis (2014) Investigative review of classification systems for emergency care – Final report. Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, Sydney. Available at https://www.ihpa.gov. au/publications/investigative-review-classification-systemsemergency-care (accessed 24 January 2020).

Health Policy Analysis (2017) Emergency care costing and classification project – Cost report. Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, Sydney. Available at https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-wedo/development-new-emergency-care-classification (accessed 24 January 2020).

Health Policy Analysis (2019) Australian Emergency Care Classification – Final report. Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, Sydney. Available at https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/ emergency-care (accessed 24 January 2020).

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (2019a) Emergency care. Available at: https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/emergencycare (accessed 10 January 2020).

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (2019b) National Hospital Cost Data Collection Report: Public Sector, Round 21 Financial Year 2016-17. Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, Sydney. Available at https://www.ihpa.gov.au/publications/national-hospital-costdata-collection-report-public-sector-round-21-financial-year (accessed 24 January 2020).

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (2019c) Urgency Related Groups and Urgency Disposition Groups. Available at: https:// www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/urgency-related-groups-andurgency-disposition-groups (accessed 10 January 2020).

Jelinek GA (1992) A Casemix Information System for Australian Hospital Emergency Departments. Report to the Commissioner of Health, Western Australia. Perth.

Clare Searson BBus (Marketing), MHSM (Planning) Manager, Classification Development Independent Hospital Pricing Authority Email: Clare.Searson@ihpa.gov.au Laura Harris BExPys, BSc Hons Neuro, MHIM Director, Classifications Independent Hospital Pricing Authority Email: Laura.Harris@ihpa.gov.au