8 minute read

A Risky Business

Irish Historical Fiction: Repossession, Restoration & Revival

It’s a good time for Irish historical fiction. Christine Dwyer Hickey won the eleventh Walter Scott Prize for her novel The Narrow Land (Atlantic Books, 2019), which explores the marriage of artists Edward and Jo Hopper. The judges praised the author’s courage in tackling a subject already explored by many biographers. Dwyer Hickey, they said, ‘embraced the risk and created a masterpiece.’ The Edward and Jo of The Narrow Land are a fascinating couple; bickering husband and wife, artist and muse, and also – successful artist and stymied artist. In this retelling of the artists’ lives, the incongruence between Jo’s artistic ambition and her lived reality as wife and muse is forensically explored.

Advertisement

Initially, Dwyer Hickey hadn’t planned to focus on the couple at all. ‘The Hoppers were supposed to have cameo roles!’ she says. I asked Christine about the exact moment Jo and Edward caught her imagination. It turns out that she was visiting Truro on Cape Cod, when the couple ‘came to her’. ‘I imagined them as a distant silhouette on a dune, viewed by another character, a ten-yearold boy, who would wonder who they were, standing there at the easels, painting under the blinding light. I had no idea they intended muscling in and taking over the entire novel!

Writing about real people is a delicate matter, balancing fact and fiction, finding the voice… ‘I found their voices literally,’ Christine says, ‘by listening to them talk in various documentaries. I read everything I could get my hands on: biographies, art books, nature books etc. And I used Jo Hopper’s diaries for specific incidents that occurred in their everyday lives.’ There’s a wonderful fly- on-the-wall quality to the descriptions of the Hopper’s volatile marriage, and a painterly quality to the writing. Some passages felt like stepping into a Hopper painting, and having it come to life around you. Christine rented a house up the beach from the Hoppers’ summer house. She wanted to experience the light, the tide, the stars, just as they had done. ‘I walked around their house,’ she said, ‘sat on the bench built by Hopper himself and imagined my way into their world. I even managed to find a packet of photographs showing the interior of the house shortly after the Hoppers died. I also visited Hopper’s boyhood home in Nyack outside New York which helped me to understand his childhood. These visits proved to be, not only the most enjoyable part of the research, but also the most useful.’

Another fabulous bio-fictional novel is Joseph O'Connor’s remarkable Shadowplay (Vintage, 2019) which won Book of the Year at the Irish Book Awards. Set in London of 1878, amidst the Oscar Wilde trial and Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror, the novel explores the relationship between theatrical stars Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and theatre manager, Bram Stoker. The novel is set before Stoker created one of the most potent characters of all time. Clues linked to the creation of Dracula are scattered throughout Shadowplay – we see how aspects of various characters, and elements from London of the time, may have made their way into the classic. Like Dracula, Shadowplay is an epistolary novel composed of letters, articles, and diary entries, which gives the reader that added, ‘oh should I be reading this?’ voyeuristic thrill.

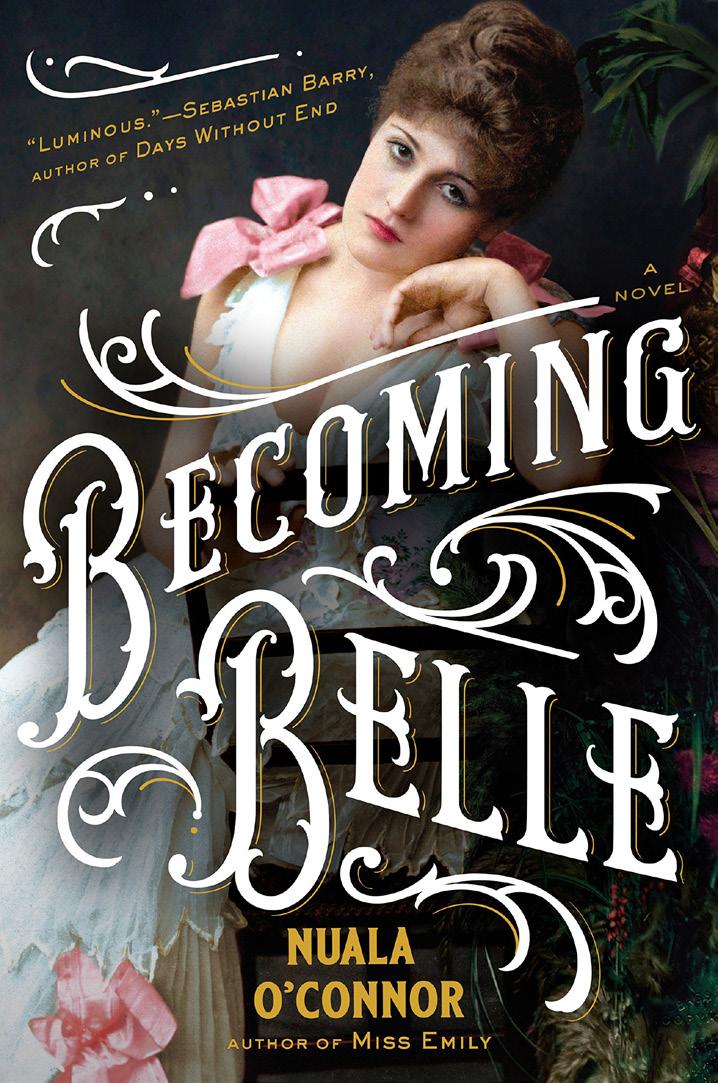

Nuala O'Connor’s latest release Becoming Belle (Piatkus, 2018) reimagines Isabel Bilton’s journey from music hall actress in London to becoming the Countess of Clancarty in rural Ireland. O’Connor is known for tackling iconic characters such as Sylvia Plath, and like Christine Dwyer Hickey with The Narrow Land, O’Connor’s subjects have often been well picked over by biographers and historians. It’s a brave route, one that takes immense skill to pull off. O’Connor responds to the challenge with gusto, loving what she calls ‘that audacious, excitable moment’ when she decides to write a novel about some like Emily Dickinson or Nora Barnacle:

"It often feels like a crazy/brave idea to write about notorious people, though one that’s so juicy there’s no question of not pursuing it. I conjure for myself scholars of Dickinson or Joyce howling in despair at the treatment their beloved object might suffer at my hands. But as soon as I start into the research and the writing, that fear fades away and a more measured excitement and satisfaction replaces it. I approach my subjects with love and respect and, because of that, I want to do them proud and I hope I manage that. I’m not in the business of hagiography, but neither do I want to dismantle peoples’ good names: I aim to present fluid, flawed humans who had extraordinary times."

When asked about her characters, and what draws her to them, O’Connor’s exhilaration and love for her work is palpable. ‘Something in the lives of these real women I write about, whether it’s Elizabeth Bishop or Belle Bilton, sparks a moment of high fascination in me. Once I move past that initial excitement, the research always, always opens out and I find these women had deep, humane, richly

unique lives. The women I want to spotlight are invariably interesting in the first place, but it’s fascinating how much more exists below my surface knowledge. I love that, the forensic winnowing out of an emotional life, a real life. I want other people – readers – to share my love of the chosen person and to understand them better, to see that, in the end, we’re all – mostly – kind of mad and lovely and doing our best.’

Nicola Cassidy’s chosen person is Adele Astaire, the lesser known sister of the legendary Fred. The brother and sister were a popular double act in 1920s Broadway, but Adele was the more charismatic performer. Like O’Connor’s Becoming Belle, there’s an Irish connection to the story. In 1932, Adele fell in love with Charles Cavendish, gave up dancing and moved to Lismore Castle in Ireland, which she also fell in love with. Fred found a new partner, Ginger Rogers, and the rest is Hollywood history.

In her novel Adele (Poolbeg Press, 2020), Cassidy turns the spotlight onto Adele Astaire once more. The author travelled to Boston University where Adele’s papers are kept. The diaries were full of anguish over her love life, her fears around infidelity, and aging. ‘It wasn’t what I expected,’ says Cassidy, ‘knowing what a strong character she was. It made her all the more human to me, full of contradictions. She was so feisty and strong outwardly, but inwardly, like all of us, she worried and fretted.’

‘Structurally,’ says Nicola, ‘I had Adele’s story already. I didn’t have to wonder what happened next, or create plot twists. I knew how the story of her life went; the challenge was in presenting it.’ The author enjoyed that part of the creative process, taking all the jigsaw pieces and putting them together. This is Cassidy’s first bio-fictional novel, her previous historical works were close to crime fiction. ‘In all my writing, I have a nugget of truth, something that really did happen. With Adele, it went to another level in that nearly the whole novel is telling the truth, as I saw it.’ Cassidy found the research very rewarding. ‘I learned so much about the era, about other performers, about George Gershwin, Winston Churchill, Charlie Chaplin. I would never have done such in-depth research if I was writing a fictional lead character.’

Sebastian Barry’s most recent novel A Thousand Moons (Faber, 2020) is a thrilling and lyrical sequel to Days Without End. Set in Tennessee 1870, A Thousand Moons relates the story of Winona, a member of the Lakota tribe, who after a traumatic attack, sets out for revenge dressed as a boy. It’s an exquisitely written novel, but that’s no surprise – Barry is the current Laureate for Irish Fiction, a position which acknowledges outstanding contributions to Irish Literature. Poet Paul Muldoon has praised Barry for allowing readers ‘to see the world differently, and to look more deeply into our own hearts. This most lyrical of myth-makers magically re-arranges our synapses.’

My great grandfather died in 1918. Like many others, he was a victim of the 1918 Flu, a pandemic that Emma Donoghue revisits in The Pull of the Stars (Picador, 2020). The author finished writing the novel just before this year’s COVID-19 pandemic was announced. Set at the height of ‘The Great Flu,’ this visceral and gripping work covers three days in a maternity ward in Dublin’s city centre. It features a real person, Kathleen Lynn. She was a 1916 rebel, suffragist, politician and doctor, who was already experimenting with vaccines in 1918. My novel Her Kind (reviewed in HNR, May 2019) is based in 14thcentury Ireland and reimagines the country’s first witch trial, the sorcery trial of Dame Alice Kyteler. Medieval Ireland is a place where few Irish writers have travelled, so I was delighted to discover Oisin Fagan’s Nobber (John Murray, 2019). Nobber takes place during another pandemic, this time, the Black Death. A bawdy and brilliant work, like Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars, Nobber has ended up being topical by accident.

My book of the year, maybe the decade, is A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ni Ghriofa (Tramp Press, 2020). The book relates how Ni Ghriofa formed a strong connection with Eibhlin Dubh Ni Chonaill, an 18th-century poet. On discovering her husband murdered, Eibhlin drank handfuls of his blood, and composed the famous lament Caoineadh Airt Ui Laoighaire, a poem that reached across centuries to the author, who in turn gave us this profound and lyrical blend of memoir, essay, history, poetry and literary mystery.

WRITTEN BY NIAMH BOYCE

Niamh Boyce’s bestselling debut, The Herbalist, was awarded Debut of the Year at The Irish Book Awards. Her novel, Her Kind (Penguin, pbk 2020), is based on Ireland’s first witch trial, and was nominated for the EU Prize for Literature. http://niamhboyce. blogspot.com/