8 minute read

Obligation to Truth

A Conversation with Amy Bloom

Among the challenges writers of historical fiction face is how to negotiate the relationship among fact, truth, and story. To create authentic settings and believable characters, we spend considerable time researching the decades or centuries in which our stories take place. The inherent risk of such research is the possibility that the facts uncovered might overwhelm the story, masking some important truth about the past behind a mountain of fascinating details that are irrelevant to the story. In a way, every novelist faces that challenge. After all, as Amy Bloom points out during our conversation, “most novels are historical fiction, since most writers don’t set their fiction in the immediate present.” Without rejecting the category of historical fiction, Bloom nonetheless says she “tries very hard not to care how people describe” her work.

Advertisement

Bloom’s debut novel, Love Invents Us (Random House, 1996), is set in the 1970s, “which I suppose is historical fiction of a sort, although not usually what we think of it as. It is, nevertheless, 50 years ago.” The wry humor that readers of Bloom’s fiction have come to recognize as a signature feature of her characters is on display when we discuss what drew her to write a trio of novels about the more distant past— Away (Random House, 2008), Lucky Us (Random House, 2014) and White Houses (Random House, 2018). Although Bloom set each of these novels in a particular decade, whether in the 1920s, 1930s, or 1940s, setting the story in a particular time period “hasn’t always been a requirement” for her so much as it’s been a requirement of the story she wanted to tell about one of her favorite subjects: love, death, family, and sex. Among other things, she’s interested in how a period of history “shapes how people can express their relationships and act on their feelings. It doesn’t necessarily change the feelings, except how much one is subject to the opinions of others.”

Her collection of short stories, Come to Me (Random House, 1993), made her a National Book Award finalist before her Love Invents Us was published. After a second collection of short stories, a longpercolating idea for a next novel took hold. “It wasn’t so much that I was compelled by the idea of ‘Oh, historical fiction!’ It was more like, there was this story I wished to tell, and it’s set in the 1920s. The heart of the novel was an apocryphal story of a woman who had come to Alaska from Russia and had wanted to go back to Russia and decided to do it by going across the narrow straits at the tip of Alaska.” Bloom had first heard the story from her father. “My family’s from Russia, and my father always said ‘What a crazy person. Who would do that? Who would go back?’ I used to think about that story when I was a girl. I thought you could only go back for love. And that was the basis for the novel, Away.”

Bloom explains how “part of the joy of writing Away was excavating what I could find of my family’s past, which was mostly in theory not in fact.” Whatever she discovered about her family’s history, she used to get at the truth behind that journey back to Russia and invented a story about love and determination. Instead of having her protagonist, Lillian Leyb, arrive in Alaska from Russia, Bloom lands her in New York. Determined to survive in a new country, Lillian finds work as a seamstress in a Yiddish Theater on the Lower East Side, becoming the lover of both the theater’s owner and his son. When she learns that the daughter she’d assumed had been killed in the Russian pogrom had survived, she becomes equally determined to return to Siberia to find her.

Research for Away led her to think more about improvisational lives, about great road trips and the reinvention of the self during the Second World War. The result was her next novel, Lucky Us, featuring two sisters, Eva and Iris, whose journey across America takes them through landscapes littered with grifters and liars and fakes, as well as some well-meaning folks. In the course of researching that novel, Bloom discovered “a first-person account by an eleven-year old boy who was interned in a camp for Germans in Texas.” Having been unaware of the existence of such camps in the US during the Second World War, the discovery led her to invent a character named Gus whose German background leads to one of the plot twists. “Sometimes the internet is great because you fall down a really fortuitous rabbit hole, but as a researcher you have to be fairly disciplined and recognize the internet’s limits.” Even if you’re writing about something significantly in the past, “you have to be aware of the fact that the past is always receding and it’s like memory: You’re going to get what you get but there’s no reason to think it’s particularly accurate. So you have to manage that, too.”

Any novelist must ask herself whether any fact uncovered in research moves the story forward or illuminates character. “I work very hard not to make mistakes,” Bloom explains, “but diverging from the facts is for me not a mistake. If I misunderstood it, that’s a problem. But if I

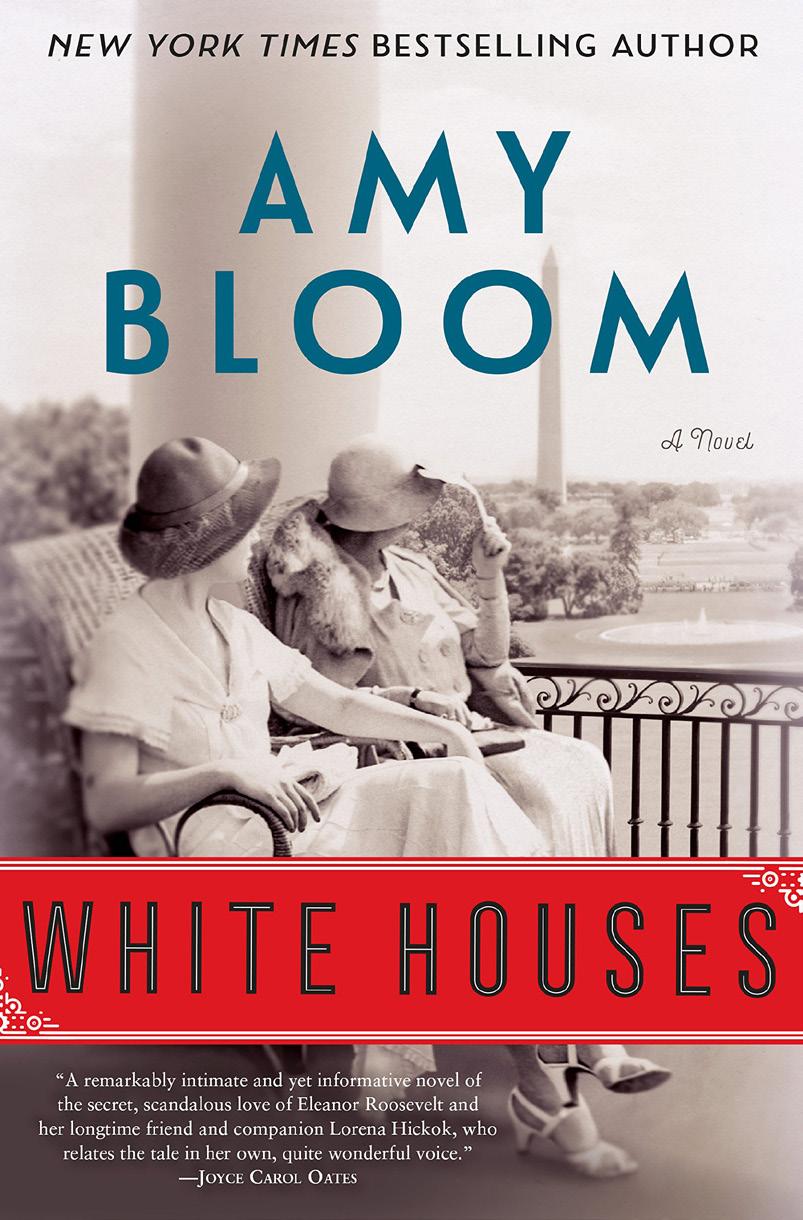

choose to write a different narrative, you get to do that, on account, it’s a novel!” White Houses, Bloom’s novel about the longstanding affair between Lorena Hickok and Eleanor Roosevelt, was the one she had “the strongest obligation to truth” since she’d put so many people in it who’d actually lived. Yet, Bloom adds impishly, “I could have made Eleanor a Vegas showgirl, but that would be a different kind of historical fiction, still set in the past. I didn’t because I wanted to sustain the historical Eleanor as a character.”

I ask Bloom what trends she sees in historical fiction. “I’m the worst person to answer that question.” When she’s writing a novel— currently one about occupied Paris during the Second World War—she reads little fiction. “I’m pretty permeable.” Early on, she was working on a novel set in the Northeast, and was reading a lot of Reynolds Price and Eudora Welty. Suddenly she found her characters, who were from Brooklyn, were saying things like “‘that dog won’t hunt.’” So, she thought, “this is a problem. Now, when I’m writing a novel, I don’t read fiction—I have enough trouble with my own characters without bothering with other people’s characters— but I read a lot of poetry and non-fiction related to my subject. And I’m a slow writer, really slow, no matter what.”

I point out that the period of her new novel, set during the Second World War, is a persistent subject in historical fiction. She agrees: “It has a lot to offer. It’s always been interesting to me the tremendous attachment the French have to the notion that practically everyone in France was in the Resistance. Except when you break it down statistically, it turns out that about two per cent of the population was in the Resistance. Not surprisingly, in the last four years in the US, I found myself thinking a great deal about who resists, who collaborates, who enables, and the way in which decent people do terrible things, which is something that is often of interest to me.”

Colette will be one of the characters in her new novel, though not the protagonist. Returning to the themes of the relationship between research and story, Bloom says her Colette “is as she appears to me to be in her own letters, her fiction, in interviews and so on. I could have made her somebody else. I could have made her Colette who owns a series of clothing stores in Paris during the war, but I didn’t make her somebody else. On the other hand, in a way, every single character is my invention.”

Bloom never fails to interweave comedy into any story she tells, or to mix spectacle with more mundane events. It’s not unusual to find circuses, theater and other forms of performance in her novels. She started out in the theater, she explains. “Nothing makes me happier than to be in the theater and specifically to be backstage in the theater. So, I don’t know if there will always be a circus or a sideshow or a carnival, but it seems quite likely that there will be. Just like there’s always going to a Jewish joke. You write as you are and there’s no hiding it. You write as you are.”

When I tell Bloom one of my favorite characters was Gumdrop, the Black prostitute in Away who rescues Lillian Leyb after she’s been beaten and robbed on the streets of Seattle, and that I found the relationship that develops between the two women fascinating, Bloom pauses for a second. “Well, they were both complicated women. The both understood lots of the limits of the world they were in and that also shaped their relationship,” she explains. “I have to say, that is one of my favorite relationships,” she adds, “‘cause I’m such a fan of Gumdrop’s.”

When I review the interview transcript, it suddenly hits me—Was that another slip of her wry humor? Did Bloom mean Gumdrop the character or the candy of the same name? Yes, I thought, Amy Bloom certainly writes as she is, telling stories rich in character and setting with enough humor to leaven the pain.

Although Bloom’s new novel is a work in progress, her forthcoming memoir, In Love, is due out with Random House in February 2022. That tantalizing title alone makes me eager to read it.

WRITTEN BY KATHLEEN B. JONES

Kathleen B. Jones is the author of the memoirs Living Between Danger and Love and Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt, as well as plays and short fiction. She also wrote Cities of Women, a novel about the illuminated manuscripts of Christine de Pizan.