35 minute read

Sarah Ann Lawton Coston

Sarah Ann Lawton Coston (1910-1995) An Oral History

From the Boynton Beach City Library Local History Archives Edited for publication by Lise M. Steinhauer

Sarah Ann Lawton Coston waving from a Stinson, 1940. Courtesy HSPBC.

Note: Oral history cannot be depended on for complete accuracy, based as it is on complex human memory and communication of that memory, which varies due to factors such as genetics, social culture, gender, and education. Nonetheless, oral history is a valuable tool in historical study. The HSPBC has noted any known inaccuracies in footnotes.

Introduction Born Sarah Ann Lawton, "Sally" graduated from Palm Beach High School, attended Florida State College for Women, and married Clarence Coston. Both she and her husband were avid pilots. After moving to the Boynton area in the early 1960s, Coston became concerned about children born into poverty and started a daycare center. It became the model Head Start program for Palm Beach County. Sally Coston's views, like all those in history, should be considered in the context of the era.

THE INTERVIEW Interviewer: Caryn Neumann, intern, Boynton Beach City Library,

for the Boynton Beach City Library Oral History Project

Interviewer: Today is August 6, 1992. I am Caryn Neumann. This interview is being conducted at Mrs. Coston’s home at [6803] Kingston Drive [in Lake Osborne area of Lantana, Florida].

Interviewer: What is your full name?

Coston: Sarah Lawton Coston. They called me “Sally” all the time.

Interviewer: When is your date of birth?

Coston: December 12th, 1910.

Interviewer: Where were you born?

Coston: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Interviewer: Where did you grow up?

Coston: I went to boarding school in Washington, DC, and then on to another boarding school in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and then I came down here [when] I was 15 and went to Palm Beach High School.

Interviewer: What line of work was your father [in]?

Coston: He was a civil engineer. Interviewer: Was he doing work down here?

Coston: Well, at that time, there was that real estate boom down here and he had some interest in real estate. He was in back and forth.

Interviewer: You graduated from—

Coston: Palm Beach High in 1927.

Interviewer: What did you do upon graduation?

Coston: I went to Florida State College for Women for two years—no. I was 16 when I graduated, he thought I was too young to go to college. So, he sent me to a Catholic—they used to call them—kind of prep school. It’s a fifth-year finishing school kind of thing. And then I went two years to Tallahassee. And then that was the Depression years, and we had three in college at that time, so I couldn't go back. I came back down here with my mother, and then I met my husband.

Interviewer: What year were you married?

Coston: 1933, right in the bottom of the Depression. Hate to think—we didn't even have any money. I mean any money. We had $10, and the ring was

$7.50 and the license was $2.50. And we stayed at my husband's home, and he started a business. My father said the best time to start a business is the bottom of the Depression. So, my husband had some training in plumbing and heating and air conditioning, and so we started a little business and it just grew.

Interviewer: What was the name of the business?

Coston: That was the Clarence Coston Plumbing & Heating.

Interviewer: How long was it in existence?

Coston: Until 1939-40, I think. No, after that, 1945 maybe.

Interviewer: After the war?

Coston: After the war, yeah. Oh, yeah, long after the war.

Interviewer: Were your children born during the Depression?

Coston: Well, yeah, they were born in 1935 and [193]7 and [193]9.

Interviewer: What did you do during World War II?

Coston: Well, we carried on the business, and then was with the Civil Air Patrol here. At that time there were a lot of submarines coming down the Atlantic, and the big planes and bombers and all. The Army and Navy couldn't see the periscopes, and they thought that these small planes—we both flew, my husband and I both had our license. I got that while I was doing these other things.

Interviewer: Wasn't that unusual, for a woman to have a pilot's license?

Coston: Very unusual, and I got a lot of criticism from people: “Oh, you have three little children and you’re flying,” like that. It was unheard of. But my husband was flying. He wanted me to, and I wanted to, and so I just did. We’d take the kids up, and they’d take a coloring book. I mean, they didn't think anything of it. So anyhow, they started the Civil Air Patrol, and they had the small planes, and they put bombs on the bottom of them. This is really crazy, and they were supposed to go from here up to Fort Pierce and look for submarines because they couldn’t see the periscopes, and then the point was going to be they would drop their bomb. Everything was so exciting, I don't think we realized that if they ever had to have a forced landing, they’d just blow themselves up. They wouldn't let me fly [for them], of course. But they did let some of the women join the Civil Air Patrol, they told us that we could go out to the airport and get breakfast for the pilots. I forget her name, but one of the debutantes from Palm Beach and I used to go out in the morning. I had a maid come up [to] take care of my children, and my mother was living there, so they were well taken care of. Then I’d go out and cook breakfast for the flyboys.

One time, I did see a periscope when I was flying. I had my friend with me, and I said, “I think that's a periscope,” and she said, “Well, it is.” She was secretary to the Civil Air Patrol. I said, “I see a tanker coming down, up there by the Breakers. They’re going to meet, that thing is going to blow that tanker up. We'd better go down and tell the Civil Air Patrol.” And we did. Amanda, she called right away, and they said, “Oh, Sally wouldn’t know a periscope from a hole in her head.” No kidding, that periscope didn't blow that tanker up. I don't tell that story often, because I guess the men wouldn’t like it very much. Anyhow, nobody was to blame. They really didn't think I could know a periscope, that was too much for a woman, I guess.

Interviewer: What prompted you to become involved with daycare?

Coston: Well, in 1959, we had a small part of our business over in the Bahamas, and we used to fly back and forth a lot. So, this day he was going to go, and I decided I wasn't. He left in the morning. Then he

Top: Sarah Lawton Coston next to a Stinson aircraft, 1941. Courtesy Civil Air Patrol Collection, HSPBC. Bottom: German U-boat submerging off the coast of Florida, 1942-1943. Courtesy Quincey Collection, HSPBC.

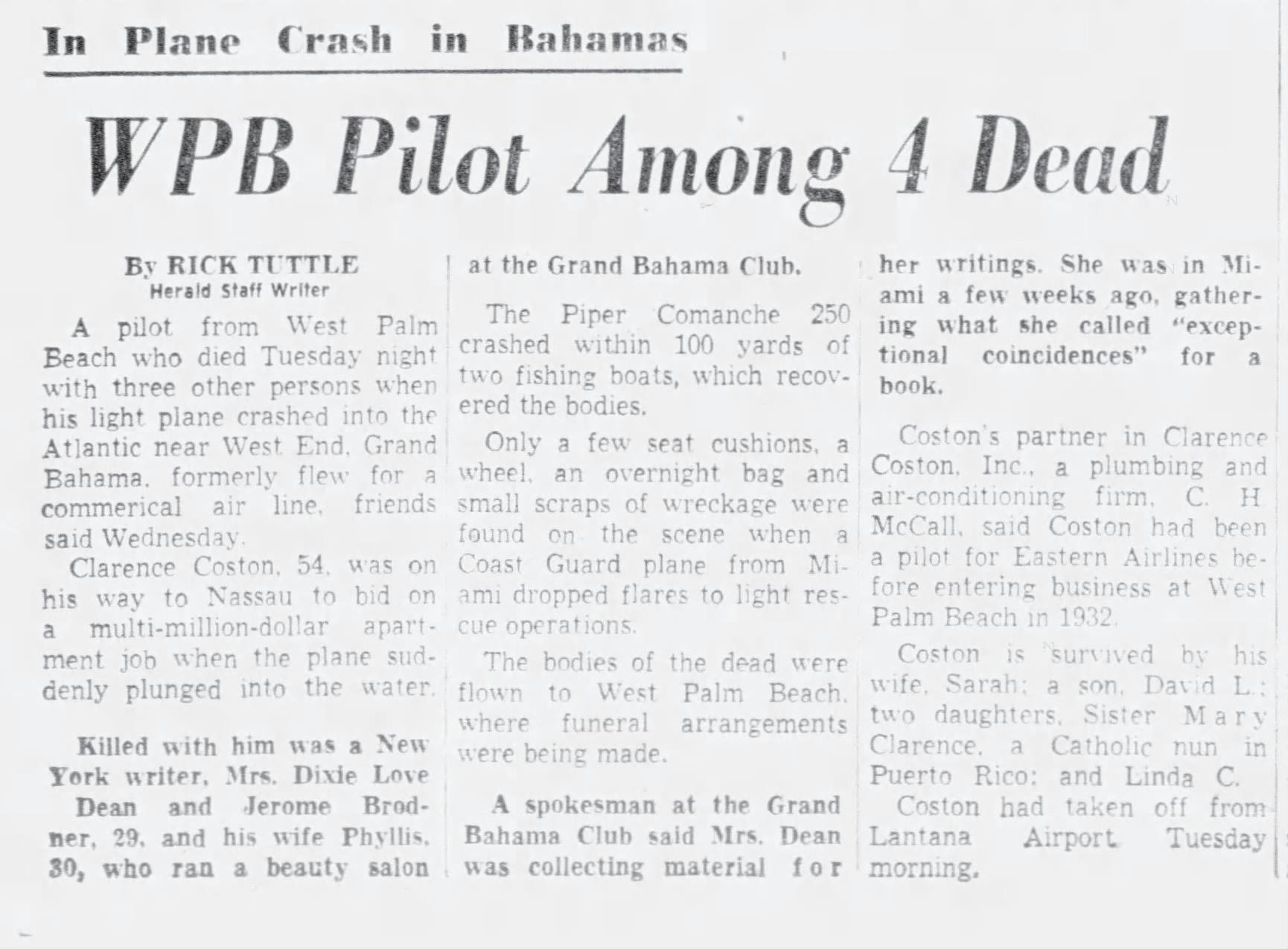

A news article published on May 19, 1960, describes how Clarence Coston was killed with Obituary for Ey RICK TUTTLE (Aged 54) three passengers on their way to Nassau, Bahamas. Courtesy Miami Herald.

Clipped By:

dmurray021

Tue, Mar 24, 2020

Copyright © 2020 Newspapers.com.

All Rights Reserved.

Clarence "Cocky" Coston in his Eastern Airlines pilot uniform. Courtesy Civil Air Patrol Collection, HSPBC.

From left, Imogene Parmalee and Sarah Lawton Coston in their Civil Air Patrol uniforms, 1942. Courtesy Civil Air Patrol Collection, HSPBC.

crashed that afternoon and was killed. Then his sort of semi-partner took over the business and promptly went bankrupt, and my son took over another part and went bankrupt. So much for men, right? So, I sold my home up in West Palm Beach and bought this. I was the only house here for a long time. I just like the scenery.

I had a Black girl helping me, Arithia, from Boynton. 1 And I was sitting here one Sunday. There was a Dr. Shapiro on, the superintendent of all the schools in Harlem, and he was saying that they were giving him a lot of trouble about children failing in the first grade, and he said, “How can they help but fail? They come to me right off the street. They can't even speak anything but gibberish to each other, and half of them don't even know their name.” He said, “What can I do, teach them to read? They don't know words, they don't have any vocabulary. These are poor children.” And I thought, God that's terrible. He said, “They've already given up. They don't hear anymore because nobody ever listens to them. Children learn by their curiosity, and their curiosity is not satisfied because there's nobody home to listen. So they quit asking questions, and then your curiosity is dead. I can't do a thing.” I thought, that's terrible, to give up at five and six. Actually, I was really crushed by my husband's death. I thought, well, maybe I could help a little bit. So, I [asked] Arithia, “Do you think you could find 10 little kids from the streets?” “Oh, yeah,” she said, “they're from the 13th, all over my street.” I said, “Tell them to come and I'll find a place.” Lake Lytal was the chairman of the County Commission. 2 I asked him, and he got Reverend Lou from one of the Black churches in Boynton. Lou arranged that I could use the recreation center, Wilson, from 9 in the morning till 11:30. 3 And then I’d have to have it all cleaned up and the City Recreation would take it over.

Arithia got, on Monday, 10 kids. I didn't know their names or anything. I had a lot of crayons and little cars and I proceeded [to] have my little class. On Tuesday there were 20 kids and on Friday, there were 65. Old ladies would bring me a strap, saying, “Here, beat this one with this.” Oh my gosh. I didn't—I was out of my mind. Arithia said she'd help me one day a week and got a couple other girls who had a day off. We finally got a group, and Lena Rahming and Arithia, they’re both there now. 4 I got my brother to come once and another man friend, who brought the Boy Scout manual. He came once, he says, “You're crazy. You can't do this.” Everybody told me, you know, I just couldn't do it, stop it, and all that, but I just went from one day to the next, and the kids kept coming, and I’d buy graham crackers and that drink in a package—

Interviewer: Ovaltine?

Coston: No, it’s grape and stuff.

Interviewer: Kool-Aid?

Coston: Kool-Aid. Nick said we'd have that about 10:00. Then the health authorities came in [and] said I couldn't do that. I think I had some plastic cups. I couldn't use the plastic cups. My brother-inlaw worked for the lumber company, and my sisterin-law was an interior decorator. She made me 65 little plastic cushions and brought them down so the kids had someplace to sit. They gave me one of those

1 Arithia Marshall (1930-2014) was born in Alabama, attended Tuskegee Institute and Indian River Community College, and moved to Boynton when her husband retired from the Army in 1962. 2 Lake Lytal set a record for serving 32 years on the Palm Beach County Commission (1942-66, 1970-78). He was called “Mr. Democrat” for his belief in using government to help the less fortunate. [Source: Kleinberg, Eliot. "Post Time." The Palm Beach Post. June 11, 2019.] 3 Wilson Recreation Center was named for Deacon Theodore D. Wilson, who convinced the city of the need for a civic center; it opened in 1961. [Source: Gill, Randall. Boynton Beach. Arcadia Publishing, 2005] 4 Lena Rehming-Williams (1944-2011) volunteered for five years, then was manager specialist for Head Start and aftercare social services for Lake Worth, Delray Beach, and Boynton Beach at Boynton Beach Child Care Center. After her death the building was renamed Lena Rahming Child Care Center. [Source: Spires, Shari. "The Head Start Struggle." The Palm Beach Post. August 7, 1990.]

Florida Atlantic University, which opened on September 14, 1964. Courtesy HSPBC.

little closets that I can keep my things in. So, I bring out the cushions every morning from the closet and these little toys I had and paper and crayon, and then a lady came down who could play the piano and she'd kind of bang on the piano. She wasn't very good, and the kids—try to teach the kids a song. Whatever anybody could do, they did. Some church ladies used to come two or three times a week. And then some more Black girls came, and Lena stayed. The health authorities said I had to close because the water wasn't hot enough, that I washed the glasses with, and then oh, I didn't have a fence around it. They were going to close it because I didn't have a fence. didn't have the fence. There was a reporter up there from the Miami Herald, and I told him what he said. Well, he put it in the paper the next day, and I got $2,000. We put a fence up. Then the health department—well, of course, they couldn't let people gather a bunch of children. I was breaking a few laws. But finally we got it straightened out, at least from January to June, and then I had to get out of there anyhow, because the city had their summer programs. I thought, oh goodness, I guess I don't know much about this. So, I went back to college. I went down to FAU and got a degree in elementary education, and then I got my masters in childcare, early childhood.

Interviewer: About what year was this?

Coston: This is 1966. They sent two men and said that I would probably have to go to jail because I

Interviewer: When did you get your master's degree?

Coston: I was 62, so that must have been [19]72.

Sarah was interviewed by the Palm Beach Post-Times about the opening of the new Boynton Beach Child Care Center. Courtesy Boynton Beach Library.

Interviewer: Were you one of the oldest students in the school?

Coston: Oh, I was the oldest one, yeah. I'm sure I was the day it opened. Yeah, I think I was the oldest.

Interviewer: You were there on the day FAU opened?

Coston: Yeah. [note: FAU opened in 1964]

Interviewer: Was it difficult going back to school?

Coston: I thought it was going to be, but it wasn't. I mean, everybody was real nice and they treated me just like another student. We had projects and we all worked together. And then I had this school open in September and used the children for projects, and every time I had like an exam, I'd bring all these children down and make them do something. I’d get an “A.” This was the best example they had, you know. They never saw children that age, three and four. I'd have them bring red blocks and green blocks and sing songs and teach them a little arithmetic and show off. Anyhow, I got through that real well, I went eight years. I worked all day and went to school at night.

Interviewer: Tell me about the children. Were they all from the lower economic—

Coston: Oh, they had to be. At that time we didn't have any records, they just came from all over. The

women had to go to work, and they’d leave a bunch of kids with some old man or woman. They were all poor, you know, real poor, so they were glad to have someplace to put the children.

Interviewer: Were most of the children from minority groups?

Coston: Yeah, most of them. We had whites and Black children and some Latins, everything, a mixture. Then in 1966 or 7, I think, [Myrtle?] came down. 5 They had asked her to start Head Start. Congress had passed that law in 1965, I think. 6 I had already started, so they asked me to be the model Head Start and I said, “Good,” cause I was still trying to raise money on the side—besides going to school and running the school. I mean, I was really worn out.

Interviewer: Was that the model Head Start for Palm Beach County?

Coston: Yeah, yeah, and in the meantime, this other friend of mine said, “You ought to get a couple of lots from the city, because you'll eventually want to be on [street name?].” So, we went to city council and told him we wanted two lots on the corner, and they didn't know that was Boynton. That was nothing over there then, you know, and they never heard of a preschool for these Black children. They gave it to me, and then we decided we'd start on building it. I put it in [the] paper, and the next day there were 16 cement blocks right in the middle of sand. Money started coming in. Then the seminary was built over there on Military Trail and those guys started coming over. 7

Senator Lewis took a big interest in the school, so he gave the Bishop from their trust and then the bishop was supposed to give it to me, $35,000. 8 Then the migrant program started, and I don't know how I got connected with them. 9 But they gave, said I could have part of their chairs and things. My brother-inlaw built some long—we still have three—wooden tables with seats attached. I used them for 25 years. I think they’re still in the playground. All that good wood, you know. Over there on the side it says we’re starting. Are we breaking ground—

Interviewer: Breaking ground in [19]67.

Coston: [19]67, ’68—somewhere over three years building because we had to do it whenever anybody volunteered or gave us some money and we'd build a little more. I was afraid the people and that part of Boynton were going to be discouraged because it took so long. We’d have to just do whatever we could that week. Everybody would say, “Sally, that thing'll fall down within a year. You can't build a building with volunteer labor, that’s crazy.” They were always telling me I was crazy. And they didn't want any part of it.

Interviewer: The building’s still there.

Coston: Then three years ago the city of Boynton decided—we started a new fund for a new building and they kind of helped us, then they took it over and added to it. We knocked most of that down. Some of it may still be the other building, but it was supposed to be all knocked down. But that's the way it was right on that corner, but there's some pictures of the

5 Arithia Marshall (1930-2014) cooked for the Boynton Beach Child Care Center from 1969, and for Head Start in Lake Worth and Delray Beach. [Source: “Increase Aid for Young, Elderly." The Palm Beach Post. July 6, 1976. AND "Arithia Marshall"] 6 In January 1964, President Lyndon Johnson, formerly a teacher in a one-room Texas schoolhouse, declared The War on Poverty in his State of the Union speech. An 8-week program launched in the summer of 1965. Due to its success, Congress authorized Head Start as primarily a part day, nine-month program. The first school year programs had started in the fall of 1965. [Source: "History of Head Start." Office of Head Start website.] 7 St. Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary was built at 10701 S. Military Trail, on 100 acres purchased by the Diocese of St. Augustine in 1955. The building was dedicated in January 1966. [Source: "Our Heritage." St. Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary website.] 8 Philip D. Lewis (1929-2012), Florida Senator and Realtor, was trustee of the philanthropic Philip D. Lewis Trust. He was friends with Coleman F. Carroll, Bishop of the Diocese of Miami 1958-68 and Archbishop of Miami 1968-1977. [Source: Oral History with Philip D. Lewis, 2006, Archives of the HSPBC] 9 "Migrant program" could refer to Operation Concern Migrant Program, 8543 Boynton Beach Blvd.

old building. I remember I took it to an architect in Palm Beach to show him the old building and see if he could design new. He said, “Well, there's nothing that can't be improved.” Now where did I put those papers, they’re all around someplace. I had them the other day. These [brochures] are all the old building. Take this too—it's a book I made. But anyhow it’s just a plain flat square, the cheapest kind you could get, and have you seen the new building? It's the biggest building in Boynton. 10 Really. What was his name, the city manager before this one? year-old and four-year-old [class]. At one time they were almost 28 on the staff. We had three or four cooks. I was the director. Assistant, secretary, and when we first started, we even had a nurse. I don’t know how we ever had that. We had a bus driver, but then they started cutting back on Head Start. They said they didn't, but they did. They cut out the A[dministrative?] A[ssistant?], the bus drivers, assistant cook, nurse. Teachers had to start getting up at six o'clock and driving the bus. Then come and teach all day.

Interviewer: Cheney?

Coston: Peter Cheney. 11 He's the one that helped me so much, the most, then they kicked him out. They froze him out, but he was the one that helped the most. A lot of people helped. I never thought it would happen. I really think it's a miracle that building got up, because nobody was really interested, except a few of us, but the city council, I think they were half afraid to say no.

There was another old man, what was his name? He used to put a bill in for so many thousand and they’d all vote yes. It just kind of wormed its way through— it cost quite a bit. I think the county finally paid for the kitchen. 12 Marvelous kitchen, we worked out of such an old crummy kitchen all those years. But my gosh, they started a little center in Delray and one in Lake Worth [in 1970], but they didn't have any kitchens. So we had to take food to them every day. Probably they’d have breakfast cereal, but we’d take lunch every day in a hot pot, we’d cook it in our little kitchen. So, we were fixing three or four hundred breakfasts and lunches every day in that little old kitchen. Miracle.

Interviewer: How many people were on the staff? Coston: Well, let me see, we had five classrooms and there had to be two teachers for each three

Interviewer: What year would this be? in the [19]70s or ‘80s?

Coston: I don’t know, let me see. I guess the ‘70s. They started cutting slowly. It would tickle me cause they'd all say on their politicking that they were going to give so many million to Head Start, and here I didn't have a bus driver. I couldn't get any equipment. I couldn't get anybody the [how many Sonora substitute?] so, of course, we kept Boynton Beach Child Care Inc., which I'd started. But this is all about being Incorporated. We couldn't get the first money because we had to be incorporated for people to get a tax exemption.

Many of these children, the bus was just letting them off in the streets and nobody was [home] till later. I found out that some of them were just wandering around, so I started an aftercare program. Head Start wouldn’t pay for that, so we got money from the United Way and different people to donate money to Boynton Beach Child Care Inc. Then we leased the building to Head Start.

Interviewer: What hours did the childcare center run and which hours did the aftercare run?

Coston: Childcare ran from about 6:30 to 2:30, and aftercare from 2:30 to 6:30.

10 The childcare center moved to 909 NE Third St, Boynton Beach in 1990. Lena Rahming credited city government with providing everything from hot dogs to this building over the years. [Source: “The Head Start Struggle.”] 11 Peter Cheney (1932-1997) was the first professional city manager of Boynton Beach, serving amid controversy 1979-1989. Lena Rahming praised him to reporters after his death. [Source: Shine, Terence. "Peter Manager, ex-Boynton manager." South Florida Sun Sentinel. January 14, 1997.] 12 The center applied for a $150,000 economic development grant in 1976, after the city council approved leasing three lots south of the center’s then current site. [Source: “Peter Cheney, ex-Boynton Manager.”]

Interviewer: Did you get support from the United Way in the late ‘70s around the Carter or Nixon administrations?

Coston: I don't know. United Way—let’s see, I got $50 the first year, I remember, so that was probably 1970. That would be a good guess. We had a board of directors. United Fund, they gave us $3,500 in 1974, so it must have started in ’74.

Interviewer: Did you charge fees to the parents?

Coston: Oh, no, no, in Head Start you can’t charge any fees, and the aftercare was kind of a joke. We were supposed to charge a dollar. We had about 35 [children] and we got back two dollars. United Way would say, “You have to show the people that you're trying to raise money on your own, so they'll know that you're helping too.” I said, “Well, it's hard down there to raise money. We're not like the Red Cross, all these uppity things.” I said, “All right, we’ll have a rummage sale.” People brought all this junk, so I had to run a story. That was, I think, a hundred and to put all this energy on that, we had to get a truck. And when we went to the flea market at Delray, we had to rent a place, so some of the girls went down at 4:30 in the morning and took all this stuff and we rented them out the truck. When we got through, we'd spent $300 and we'd only made $100. I said, “Okay, here’s our fundraiser.” I think we did try to give a dance once [and] the cook’s husband had a heart attack. I don’t think we made more than $25. So much for our fundraising. Nobody wanted to give to poor Black children at that time. It wasn't a thing. It wasn't a prestigious thing to do, it's better to give to the cancer fund, go to the dance, or the heart fund banquet, or something like that—I know the Heart Ball was a big deal. 13 Somebody said, “Why don't you have a golf tournament?” I said, “Are you kidding me?” They didn’t understand that we were dealing with people that didn't have two nickels. God, they were lucky to get something to eat. So, churches started donating cans of food and

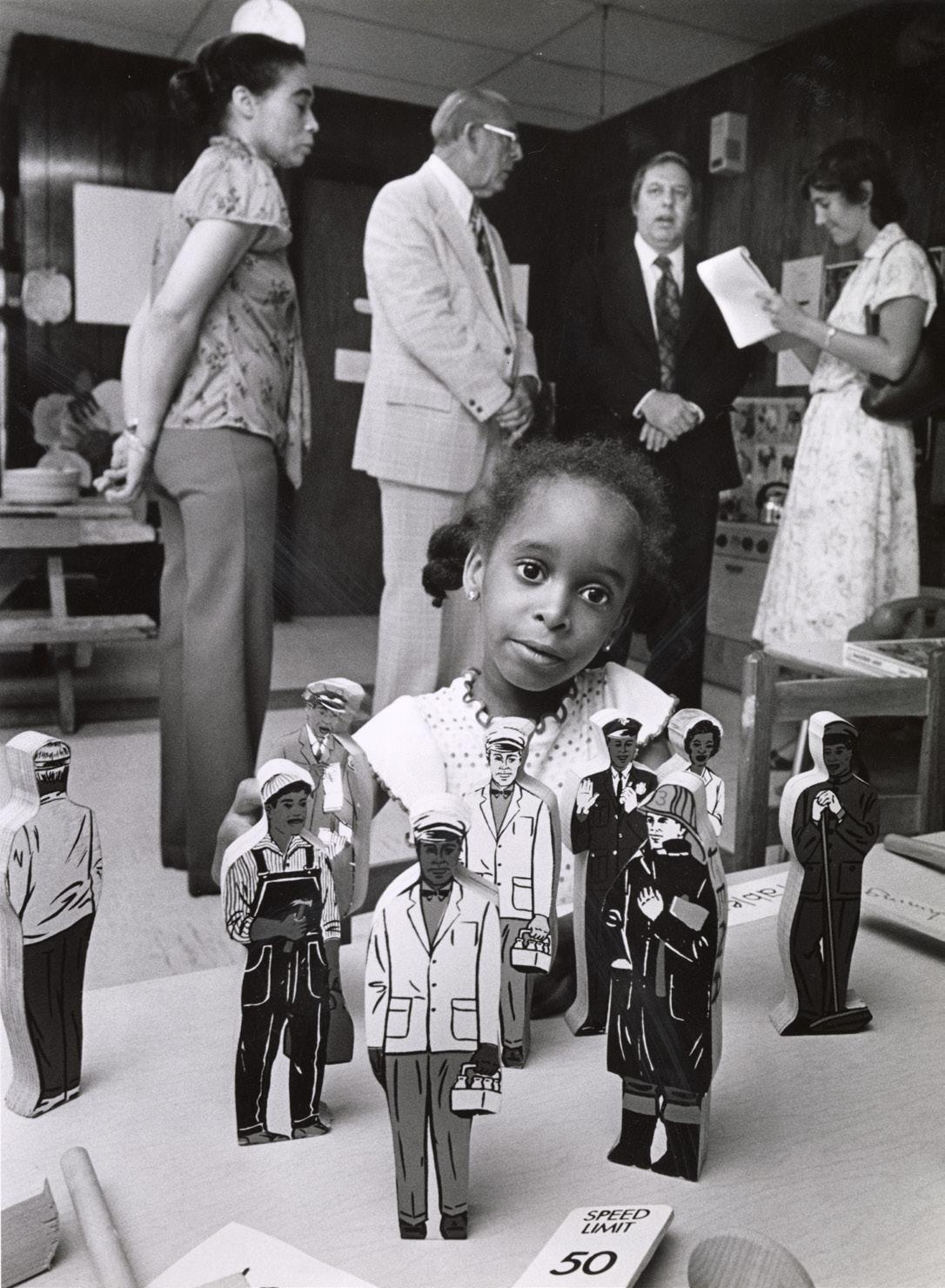

Georgette McCray plays with toy figures at the Boynton Beach Child Care Center, as County Commissioner Norman Gregory chats with others. Courtesy Palm Beach Post Collection, HSPBC.

that sort of stuff. We did start giving that away, and people kept bringing old clothes. We gave them to the children and to the families all along. We didn't pile it up, cause lots of times we were the only place they could go if they didn't have anything to eat, or any clothes for their children, sometimes a place to stay all night. We'd call Saint Vincent De Paul or Salvation Army and try to get help.

Interviewer: Was the center affected by the Civil Rights Movement?

Coston: No. That was in what year?

Interviewer: The 1960s and 1970s.

13 The Palm Beach Heart Ball each February benefits the American Heart Association and in 2020 celebrated its 65th year.

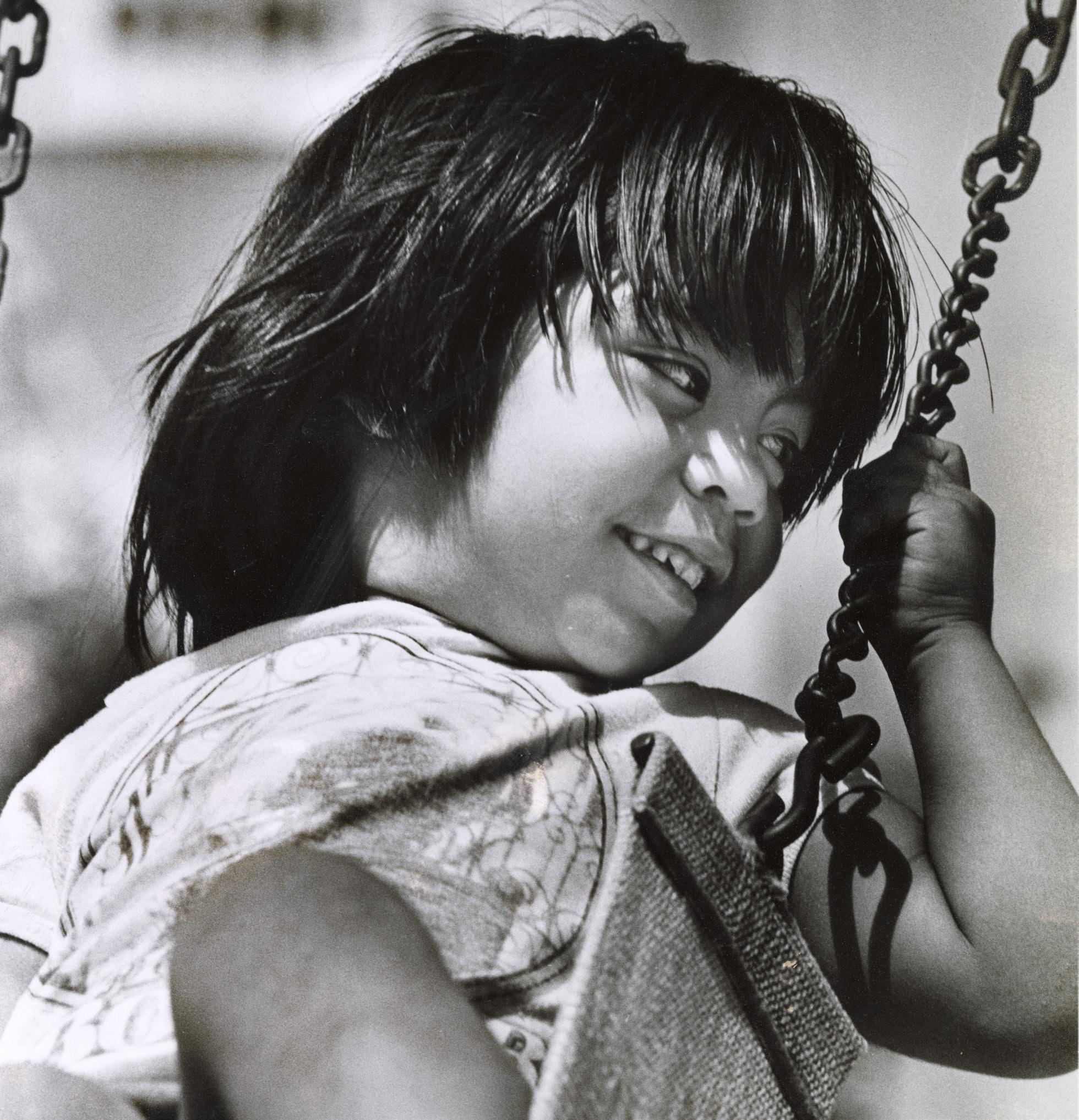

Jessica Morales plays on swings at the Boynton Beach Child Care Center, 1981. Courtesy Palm Beach Post Collection, HSPBC.

Coston: Well, yeah, we were right in the middle of [it], 1965.

Interviewer: I'm looking at an article that says the City may renege on contributions to Child Care Center. Did you get a lot of opposition? Did you have a lot of trouble getting funds?

Coston: The Palm Beach County Community Action Council was the first one. They were appointed to receive the funds. We were to come through them, and they were always having trouble, always in trouble with the commissioners, law—and nobody was really for having schools report [at-risk] children. This is the South, let’s face it.

Interviewer: Did anybody oppose you supporting working women? Today a lot of people seem to oppose childcare centers because it encourages women to leave the home and go out and work.

Coston: Oh, yeah, laugh at that.

Interviewer: Was there anything like that?

Coston: It was in the papers, but not down at that level. Nobody bothered [if] women from that culture have worked, and especially around here. They've all done, in Palm Beach, they’ve all done housework, and the men were glad. They knew they'd have to take care of them if they didn't work. There was never any of that stuff. It didn't sift down to that level.

Interviewer: Was the childcare center used for other things, such as cheese distribution?

Coston: Food? Yeah, we still distribute food every week. Churches gather the food, some of them, and they bring it over to the center. Then I think we take it someplace and give it out; we've always dispensed food and clothing and help. A lot of mothers, for instance, never get to go to the dentist because they don't have any place to keep the children. I was hoping we have a place where they could leave children and mothers could take care of themselves a little bit, which of course it turned out. We did help, but I think this was all because it was a confrontation between the county commissioners and the city commissioners.

Interviewer: Were you ever involved in politics or on any political board?

Coston: No, I was just going to straighten the world out all by myself. I never even thought. I was just going to take 10 children, period. I never thought it was going to end up with all this.

Interviewer: How many children were in the center at the time of your retirement?

Coston: One hundred thirty. Wait a minute, maybe not that many. A hundred, anyhow. I retired in 1978. I stayed on as executive director of Boynton Beach Child Care Inc., because I was still overseeing everything, but I wasn't directly involved in Head Start. We had a head of Head Start down at the school, and then we had another woman. Lena had taken charge of the building, and I was just kind of helping to run the aftercare and different charities that we were interested in, and a lot of involvement in the movement down in Boynton, like Black Awareness Week. Lena works in the school, she always heads that, and we contributed, of course. I always go to it. We give out prizes, stuff like that, I do a lot of little things down there. We still get money from the city for aftercare. I don't get United Way money anymore, because we decided that we didn't need as much as when I was buying stuff for the playground and clothes for the children and trying to furnish the school and buying materials. Now that we're doing that, we didn't really need United Way in the way that other agencies did. We could use some more money for things, like holidays, things we like to do for the children, it was too much work with United Way. There's so many papers. They had helped us when they could. They were a big help.

Interviewer: What were the ages of the children? Three and four in the aftercare program?

Coston: Well, some of the children who were already in something, some of their older brothers and sisters or some kids from Poinciana School would be brought over, like 35 or 40 around 2:30 and then at 6, maybe only one or two. The parents would come and pick them up when they got off work. They still do that.

Interviewer: What activities did the children participate in? What would be a typical day?

Coston: A typical Tuesday, they’d come at 6:30 [a.m.]. The cook would get there, we’d both get there because it was dark and the children would start coming in about quarter to 7, maybe the mothers worked at 7, and I’d keep them in the office until a teacher or an aide came. They'd have breakfast about maybe 8:00, and then the bus would be bringing children in in the meantime. Their classes

Ricky Guzman, an enrollee at the Boynton Beach Child Care Center, arranges his hat and manages a smile, 1980. Courtesy Palm Beach Post Collection, HSPBC.

would start, and they'd have a little bit of colors or numbers. We had a Peabody course 14 that was instituted by the University of [Pennsylvania?] in Philadelphia for preschool, one of the finest teaching materials in the country at that time, and the nuns had given me one. I have an older daughter who's a nun, and they'd given me one and another nun gave me another one from her school, and then we bought some, so all the teachers had the Peabody Guide. The teachers didn’t have degrees, remember, they were just from the neighborhood—Head Start didn't want anybody in there except the poor, which wasn't too bright. If you want to teach children, I don't say you need a degree, but you need some training. The book trained them, I think we got some good teachers and it taught them colors and a lot of words. Their vocabularies were so limited. They didn't know “in front of,” “decide,” “near,” “across,” “around,” or “behind,” all those words. They didn't know any adverbs and not many adjectives, they

14 The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test was created in 1959 by Dunn and Dunn and updated for decades. [Source: “National Longitudinal Surveys." U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics website.]

just used probably a verb and a noun. They didn't have any equipment to learn to read. This was the idea, to give them a larger vocabulary, which we did with all these activities with art and music. We had a music teacher, would come in and play the piano, and they learned songs. We had shows at Christmas and Easter, graduations. They were good, too. When we had them over at the seminary, even the bishop came. He died laughing; it was so funny.

Interviewer: Did you teach the children hygiene, like brushing their teeth?

Coston: Well, I had a lot of ideas and when I first went back to school, they had somebody from the health department come and this video showed that eating an apple was five times, ten times better than brushing your teeth—it got more of the debris out of your teeth than a toothbrush ever would. I've known people that didn't brush their teeth till they were 30 and they've never had a cavity. A lot of things that people used to eat; they didn't have toothbrushes. But we did because they said we had to, so each one had his little toothbrush with his name above it. We had toothbrushing time, I just did this show, really. Hand washing time at lunch. They all had to wash before they [ate] and I made them say—call it a little prayer, whatever you want to, but I made them say something. They used to say, “Thank you God for this food,” that was about it. The reason is that at the beginning, somebody would say, “Oh I don’t like that,” and it would go all around the room. Finally, I made everybody say, “Oh, what a nice lunch.” So, from then on, everybody hollers, “Oh what a nice lunch!” It's a little trick, but they never said that again, that they don't want this or that. They ate and they ate well; we had good, nourishing food too.

Interviewer: What kind of food?

Coston: We had a person that had a Head Start. They had a director of nutrition who had a couple of degrees. She’d go around all the schools and give us menus, and we'd follow the menus.

Coston: Yeah, two vegetables, maybe a green vegetable, maybe a little dessert. And maybe a little protein, whatever, fish or meat. Very good food. Oh, I could see the difference from the time a child would come to us, end of September. Honestly, by October their eyes were shining, and they were just different from getting milk and good food. And how they couldn't wait to get there, because there was something to do and people who cared about them. Not that their parents didn’t, but their mothers had to go to work. And here they were loved and taken care of—they knew it—and had good food, they started to sparkle. I could see all the difference in the world.

Interviewer: The center operated from September to June?

Coston: Yeah.

Interviewer: What happened during the summer?

Coston: Well, in the beginning, Head Start was funded to go year-round, but this is another thing that didn't happen. Congress just kept—I’m telling you, they kept cutting back. We couldn't operate all summer. We didn't have the money. I was very much against letting the children just go out, so one summer, a couple of summers, we got a migrant bus. The seminarians helped us, and we all volunteered and took the children on little field trips a lot, stuff like that.

Interviewer: Where would you go on field trips?

Coston: Oh, where we’d go? We took them to the ocean and up to the Coast Guard. This [points] used to be all farmland, and we’d take them out here, they’d never seen a cow. The farmers would all welcome[us]. This was a horse farm down at the end of the street, and this was all cow and pasture, and they had a big farm. We'd call the people, and they

loved having them. We’d bring the whole troop in. I have some funny pictures down at the center in my office of the children on a cow, and they’d never seen a cow. Terrified. We’d take them all around, just for a ride. We did a lot of things just on our own. Wasn’t organized how it is now. We can't do anything unless it's on paper.

Interviewer: How would you help a child develop independence?

Coston: It depends. A lot of them didn't want to use silver or didn't want to eat. They’d want to just pick up the food and put it in their mouths, and we had to teach them how to eat, really. And we taught them how to go to the bathroom nicely and to stay in line and obey. We taught them how to respond to a direction. I mean, if we told them to bring us something, they’d go get it and bring it right to us and we'd say, “thank you,” and if we gave them something, we taught them to say “thank you.” What we've tried to supply was what most children—I wouldn't know whether you'd say “middle class” or not, what all class of children—learn at mother’s knee, but they didn't have the opportunity because of poverty. Their mothers had to work. So, we tried to teach them what they would have learned, manners and how to cooperate and when they finished their lunch, go to the container and scrape their plate off and put it over in the pile. We’d write the parents all the time to come have lunch with them or watch them, and the parent [would say], “Is that my child cleaning his plate off?” They couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t barely believe it. They all had nice manners, and I never heard any crying. There's no reason to cry because if they ever got in a little spat, we’d make them stay away from the playground or put them in a special area for a little while. They’d know they had to do that.

Interviewer: Did you ever meet any of the children when they were grown up?

Coston: Oh, yeah, there's a lot of them come back. Yeah, Reese's daughter, I think I have her picture in there with a baby. I was in that other one. I wish I could find that first folder that she was nine months, while Arritha was pregnant. She had to bring the baby as soon as she could, so we had her from the time she was about eight or nine months, I guess. Estelle now works for Time Magazine. She's over in Tampa—married, of course—and Lena’s son's a lawyer. He went to Howard [University].

Interviewer: So, they moved up quite well.

Coston: Oh, yeah. Head Start—if you followed the principles that they started in that little thing, I think that booklet that’s in there, the principles of Head Start were well thought out. In fact, I'd like to have all that literature I had in the beginning from Head Start, because they really had a wonderful committee in Congress who thought this up.

The Boynton Beach City Library has led several oral history initiatives over the years, with the help of staff and volunteers. Thanks and credit go to many individuals for preparation, interviewing, transcribing, digitizing, and creating access, and to several organizations for their generous funding, including the Boynton Beach Historical Society.

Copyright of the original transcript belongs to Boynton Beach City Library, which has given permission of reproduction to the Historical Society of Palm Beach County. The HSPBC has edited the transcript for space and clarity for publication. The original audio and transcript are available at https://archive.org/details/ scoston1992oralhistory/scoston1a.mp3.