5 minute read

The Builder Book: A DIY Guide

“ Local history is waiting to be unearthed, with just a bit of perseverance.

by SUSAN GODSHALL and JACK TRIPP

Susan Godshall is a retired lawyer who enjoyed a career in municipal administrative law with a focus on New Haven’s economic development. Jack Tripp is currently a student at Harvard Divinity School, with his studies focusing on the religious experience in literature.

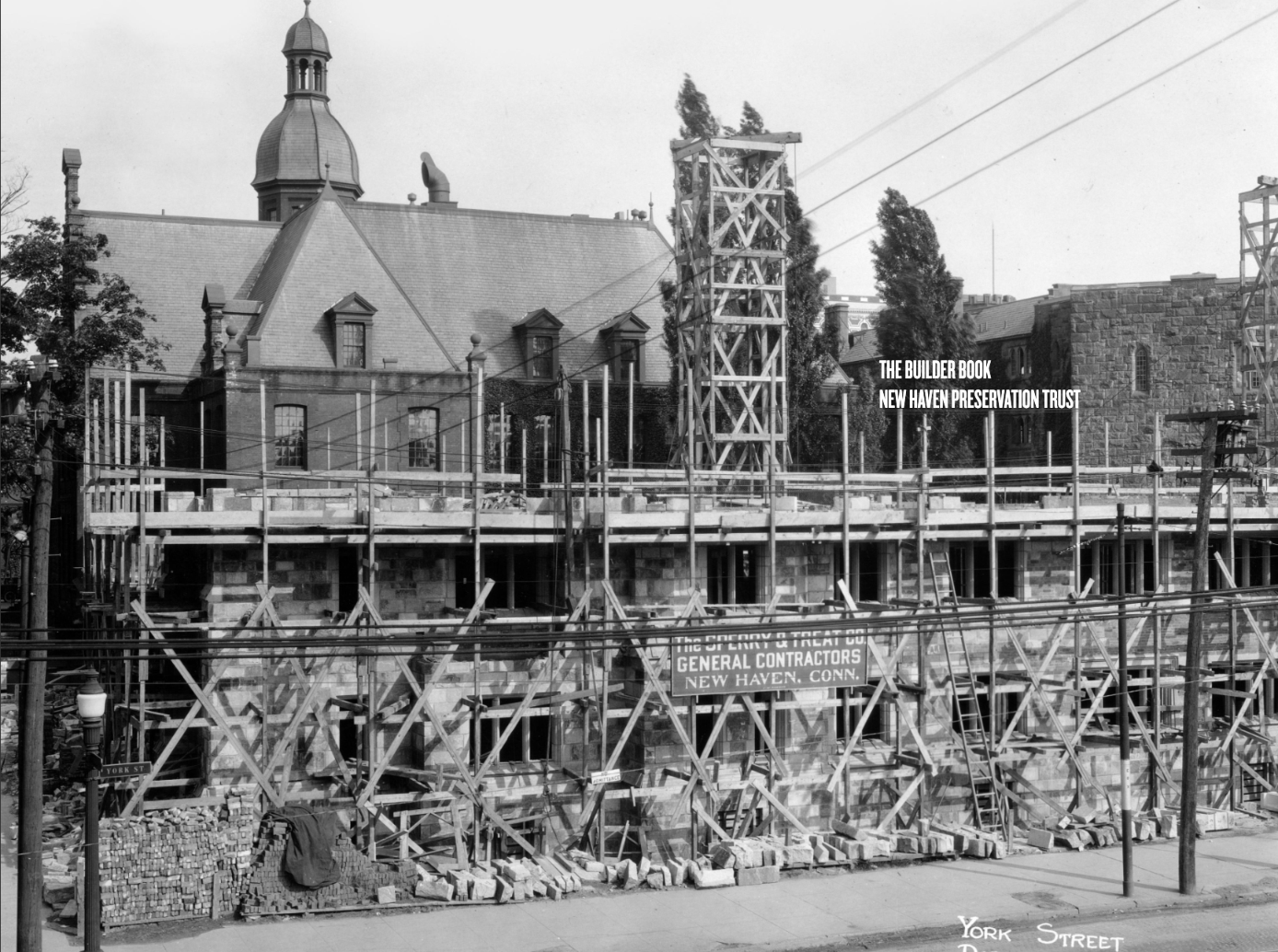

The Builder Book: Carpenters, Masons and Contractors in Historic New Haven won the 2023 Honor Prize at the Historic New England Book Prize Awards. Co-authors Susan Godshall and Jack Tripp share how they found information about the colorful cast of characters who built New Haven and whose stories are often absent from architectural histories—and tips for how to research builders in your town.

It might be reassuring to know that despite its Historic New England prize-winning outcome, writing The Builder Book was an experience in learn-as-you-go. It began with a curious observation: For most historic buildings, the architect gets credit, but the builder is unknown. Who were these builders and craftspeople? We wanted to recognize the men (and one woman) overlooked in the written record, since they built many iconic structures still lining the streets of New Haven, Connecticut.

A similar project may lie under the surface in your town; our experience offers a head start in ending it. The secret is that local history is waiting to be unearthed, with just a bit of perseverance.

The keys to unlocking this secret are libraries and community archives, the treasure chests of history. Without these resources, we could not have written e Builder Book. We relied on the deep collections of the New Haven Museum, the New Haven Free Public Library, and the Institute Library.

Community archives hold all kinds of publications. For example, city directories stretching back to 1840 offer addresses and death dates. Most nineteenth-century newspapers covered land purchases, property tax data, and commissions for new houses and shops.

Local historians wrote huge tomes filled with biographies of city residents, providing snapshots of thousands of citizens. We found one collection written by Edward Atwater, History of the City of New Haven to the Present Time (1887), and discovered that he was the son of Elihu Atwater, a mason we were researching. It soon became clear that many of these people knew (or were related to) each other, a surprise that repeated itself throughout the research.

Our favorite source at the New Haven Museum is a scrapbook collection of around 150 volumes compiled by Arnold Guyot Dana in the early twentieth century. Dana was a hobbyist with a fixation on the built environment, a gift to those interested in the street-by-street growth of New Haven. He organized these volumes by address and filled them with reams of newspaper clippings, photographs, pages from books, and other paraphernalia, now scanned for public use. We could find the Chapel Street volume, for instance, turn to the page on No. 1032, and see the original Gaius F. Warner House, designed by Henry Austin in 1860, showing its Italianate facade and ornate portico before a later addition gave it a four-story commercial face.

As we dug deeper, we learned that in addition to being skilled workers, the people we featured were creative artisans, often using their own plans and designs. They were respected in the community, took leadership positions, and frequently held appointed and elected office. Discovering this aspect of the builders’ lives— that they welcomed civic responsibility—was a bonus, illuminating history in a way that bricks and mortar alone did not.

It was only after finding all the dates, addresses, anecdotes, and bits and pieces about wives and families that we could begin to create a narrative, turning a thousand random facts into twenty-three interesting stories. To vary them, we juxtaposed the relatively famous (Sidney Mason Stone) and the unknown (Ettore Frattari), the ancestral New Englander and the Italian immigrant.

The story of one of our favorite builders brings these themes together. Atwater Treat (1801-1882) was easy to research. He appears in the compiled biographies and in the Dana scrapbook, and New Haveners commemorated him beautifully upon his death. Like others, he received a vocational education and began learning carpentry as an apprentice when he was seventeen. He contributed to both residential and commercial buildings, including the Exchange (1832)—the first fully commercial structure in New Haven.

But what interested us most had little to do with his building experience. Treat embodied the civic engagement of the time. Later in life he became a religious leader, founded libraries, helped to save the New Haven hospital from bankruptcy, advocated for abolition, and supported Black education and suffrage.

Treat’s biography shows the extent to which these carpenters and masons could also be community builders. His obituary talks about his buildings “bearing witness by their own symmetry and solidity, to the beauty and strength of character of him who built them.” His life demonstrates the intention builders brought to both their vocations and their lives in public service.

Read a digital edition of The Builder Book at www.issuu.com/nhpt.