6 minute read

Dressed to Express

DRESSED to ExpressThrough fashion, nineteenth-century women articulated individuality, identity

by CATE CARVER Guide, Otis House An independent researcher with a focus on nineteenth-century dress history, Cate Carver is a hobbyist historical costumer.

In nothing are character and perception so insensibly but inevitably displayed as in dress, and taste in dress.

Mary Eliza Haweis in The Art of Beauty (1878)

Mary Todd Lincoln’s purple velvet skirt, shown with daytime bodice, is believed to have been made by Elizabeth Keckley, who endured brutal enslavement before buying her freedom and becoming a successful dressmaker. Smithsonian National Museum of American History, bequest of Mrs. Julian James.

It’s difficult not to acknowledge that we make some of our first judgments about a person based on their clothing. The age-old warning to not judge a book by its cover, while wise, does not always reflect real human behavior. However, the silver lining of dress as a “second self,” as nineteenth-century author Mary Eliza Haweis put it, is that the wearer can use it to deliver messages. It’s the seat of personal expression—something that for many women of the 1800s was otherwise extremely limited. Women of the late nineteenth century faced a double standard, as so many had before and still do today. The “New Woman” archetype was becoming popularized in the media, especially from the 1880s through the early 1900s. She might ride a bicycle, smoke, hold a job outside the home, or even attend university. She was mocked and praised as well as reviled and celebrated, leaving women to tread the fine line between too conservative and too forward-looking. In reality, women remained subject to many of the same strictures that had been imposed upon them for decades— among them, the idea of shunning public attention. Women who sought careers in the visual arts often ran up against this concept as a barrier to their professional lives. Women’s artwork might grace a family parlor, in the form of a watercolor or a piece of needlework, but it ought not appear in the Paris Salon. Female writers fared little better, often being obliged to write under androgynous pen names if they wanted to achieve widespread success. With pathways to self-expression so rigorously controlled by the male powersthat-were, it’s no wonder that fashion and dress came to represent a primary avenue of identity expression for many women. And for those who faced intersectional oppressions—Black women, immigrant women, workingclass women, and any combination thereof—taking that route was even more necessary.

During the Gilded Age, print media expanded massively. New magazines and other publications brought the latest fashion plates from Paris into the homes of American women. Advertising culture experienced a similar boom, with the birth of modern-style celebrity endorsements (noted beauty and British actress Lillie

House of Worth afternoon dress. Influential French designer Charles Frederick Worth sparked an 1880s revival of the bustle skirt. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; gift of Mrs. William E. S. Griswold, 1941.

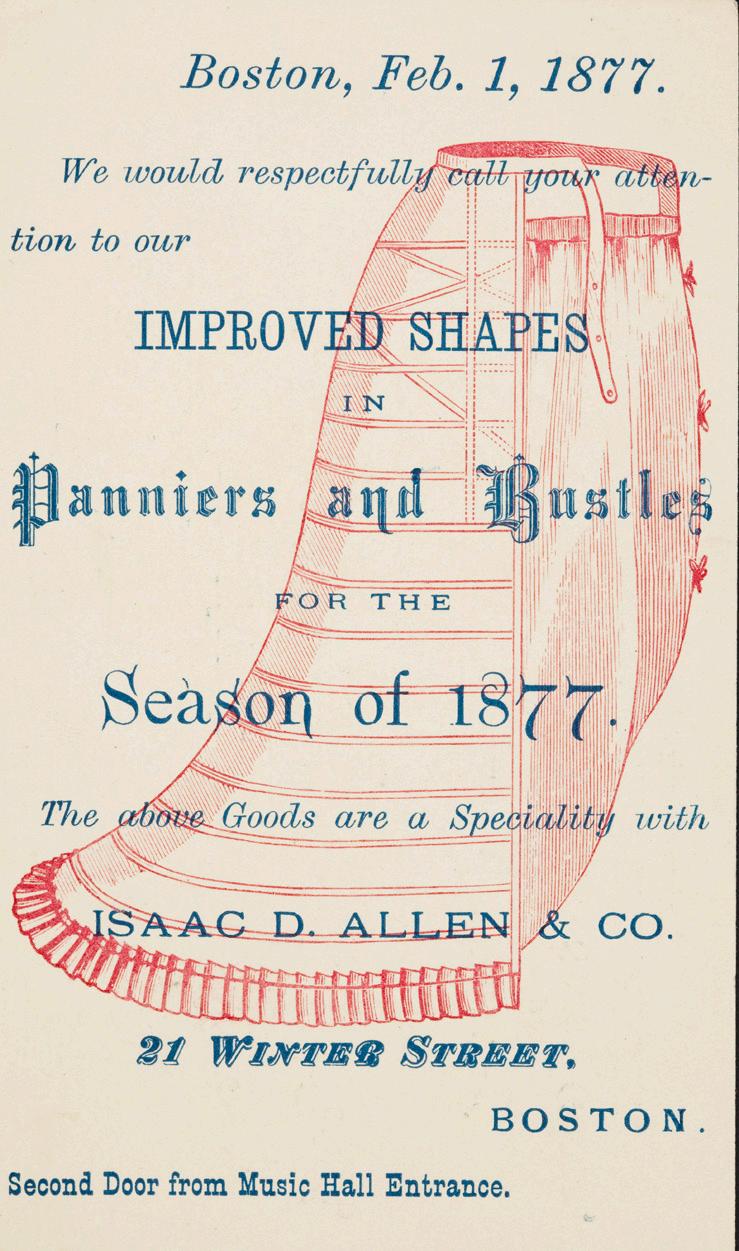

Godey’s Lady’s Book illustration of fashions for February 1865. Trade card for Isaac D. Allen & Co. in Boston, which specialized in gloves, corsets, panniers, and hoop skirts. An image published in an 1862 issue of Punch depicts a woman demeaning a domestic worker for wearing a crinoline: “Mary! Go and take that thing off directly! Pray, are you aware what a ridiculous object you are?”

Langtry, for example, endorsed Pear’s Soap in 1887). Suddenly, a woman might know—or think she knew—exactly what beauty products her style icons used. Styles also changed much faster than before, on a global scale; a brief trend among the English elite might make its way into that month’s edition of a magazine published in Boston and there find new life. Since these smaller fads and crazes were mostly driven by groups of women rather than large fashion houses like that of Charles Frederick Worth, this rapid ebb and flow of

styles represented one way women could exert influence on the visual world around them.

Fashion also experienced greater democratization during this period. New industrial technologies made stylish dress easier to achieve than ever before. The cage crinoline, or hoop skirt, is a perfect example; after its introduction in the late 1850s, it quickly became relatively inexpensive to produce and therefore was low priced. Women from all walks of life could embrace the latest styles in skirt shapes, from Mary Todd Lincoln to enslaved women, whose scant free time was precious. Naturally, this created quite a stir in the upper echelons of society. Satirical cartoons in magazines like Punch mocked maids who “dressed above their station,” with one 1862 illustration showing a wealthy lady berating her maid for wearing a hoop as large as her own.

Moving beyond crinolines in particular, newly freed Black women faced far more extreme challenges in claiming fashion as their own. Perturbed by the abolition of slavery, botanist Henry W. Ravenel, a South Carolina plantation owner and slaveholder, complained in 1865 about seeing “Negro women drest [sic] in the most [outlandish] style, all with veils and parasols” on the streets of Charleston.

However, besides being trendy, fashion could also represent economic opportunity for women who faced oppression beyond that of their gender. Mary Todd Lincoln may have worn an inexpensive cagecrinoline, but the gowns it supported were made by Elizabeth Keckley. Born enslaved (the plantation owner was her biological father) Keckley eventually managed to buy herself from the brutal family that held her. She went on to become the most celebrated modiste (a person who makes women’s fashionable dresses and hats) in Washington, D.C., during the Lincoln presidency. Though few confirmed examples of Keckley’s work exist today, those that remain are noted for their elegant simplicity, clean lines, and harmonious color coordination.

The “Trends Men Hate” lists that emerged during the 2010s are far from a present-day phenomenon; Victorian-era men often reacted to styles women loved with anxiety and derision. Punch, ever willing to offer an unsolicited opinion, featured many cartoons during the hoop skirt era depicting baffled men unable to get close to the women around them. The bustle was similarly mocked in its day, with images comparing women to centaurs; closer-fitting “natural form” skirts drew analogies to beetles. The medical establishment was quick to throw its two cents in as well. Corsetry in particular drew a great deal of ire, with dire warnings about broken ribs, miscarriages, and death by asphyxiation. (Few if any of these stories have been confirmed to the satisfaction of modern-day researchers.) In a perfect illustration of the classic double standard, The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine published a series of letters promoting extreme tightlacing in the 1860s that many modern historians agree were most likely anonymous works of fetish fiction, probably written by men. In spite of this “giving with one hand and taking with the other,” most corset advertisements of the period mention comfort as a selling point, and the corset remained a primary means of breast and back support until the late 1910s.

In many ways, women of the late nineteenth century found their attempts at self-expression stifled at every turn. It was doubly difficult to assert one’s independence if multiple axes of oppression were in play, as with Black women, working-class women, or those who were both. However, through their personal style choices, women at all levels of society managed to find their voice. British author Mary Eliza Haweis called dress “the second self, a dumb self, yet a most eloquent expositor of the person.” With this muted self, women of the Victorian era could

An unidentifed woman c. 1890 in Tallahassee, Florida. Of the approximately 1,500 portraits made by photographer Alvan S. Harper (1847-1911) many of them are middleclass African Americans. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.