20 minute read

Mixing cover crops and manure

MIXING MANUREAND CROPSCOVER

Cover crops can capture leachable nitrate — but do they take up too much nitrogen in the process?

Advertisement

by Matt Ruark

Corn silage production offers a great opportunity to plant cover crops for erosion control and water quality benefits. In Northern climates, cover crops can be hard to establish following grain harvest, but if corn is harvested for silage by late September, grass cover crops can grow quickly and provide valuable ground coverage.

Winter rye is the most popular cover crop in this scenario, as it will survive the winters in the northern U.S. and provide benefits up until termination in the spring. Other popular grass cover crops include oat and spring barley, which can grow quickly during the fall but will die off during the winter. This has the advantage of reducing an extra trip across the field to terminate the cover crop, but the dead biomass may not provide adequate erosion protection in the spring.

Concerns about fall application

Many questions still remain when using cover crops, especially when manure is applied in the fall. While fall applications are essential to overall manure management, application at this time does create risk of nitrate leaching into groundwater or to surface waters via tile drainage. Cover crops can help trap leachable nitrate during the fall and early spring months before planting. We do not expect, though, that this “trapped” nitrogen will be returned to the next corn crop.

The question at hand is how much nitrogen from the manure is left for that next corn crop? In a perfect world, the cover crop would just trap the nitrogen that would be leached, but recent studies in Wisconsin have revealed they also tap into the nitrogen that would be available

Figure 1. Spring barley growth of about 800 lbs./ac of dry matter in Dane County, Wis., in November 2015. Figure 2. Winter rye growth of about 1,500 lbs./ac of dry matter in Grant County, Wis., in April 2015. Figure 3. Winter rye growth of about 2,500 lbs./ac of dry matter in Dane County, Wis., in April 2017.

for the next corn crop.

Between 2015 and 2018, cover crop research trials were conducted in Wisconsin at the Arlington, Lancaster, and Marshfield Agricultural Research Stations (located in Dane, Grant, and Marathon County, respectively). In each study year, cover crops (winter rye, annual ryegrass, and spring barley) were planted following a corn silage harvest and an application of liquid dairy manure of about 10,000 gallons per acre, which typically provided about 80 to 100 pounds of nitrogen (N) per acre (lbs./ac).

The different cover crop species were compared to plots where no cover crop was applied. The following year, corn was planted 10 to 14 days after the winter rye cover crop was terminated (spring barley and annual ryegrass winterkilled). Eight rates of N were applied to determine differences in the amount of N needed to optimize corn yields.

Evaluating nitrogen needs

The results of this study revealed three different things. First, if using cover crops that winterkill (such as spring barley), there was no reduction in the manure N credit for the next corn crop. Typically, spring barley produced 1,000 lbs./ac of dry matter biomass or less (Figure 1).

Second, when winter rye (a cover crop that consistently survived the winter) produced less than 2,000 lbs./ac (Figure 2), then about 35 lbs./ac of extra N fertilizer was needed to maximize the next year’s corn yield. This result indicates that the winter rye reduced the “nitrogen credit” of the manure.

Finally, when winter rye biomass exceeded 2,000 lbs./ac, the expected nitrogen value of the manure to the next corn crop was eliminated. This indicates that while getting enough cover crop to provide erosion control (about 1,000 lbs./ac) is good, when the cover crop gets too big it begins to act as a cash crop and utilizes most, if not all, of the nitrogen in the fall-applied manure. Nitrogen adjustments based on cover crop biomass are presented in the table.

Since our research was conducted with the fall applications of manure, we are attributing the need to apply additional nitrogen fertilizer to the fact that the cover crop physically took up a lot of nitrogen. There could also be nitrogen immobilization that occurs when the winter rye cover crop decomposes. This is where soil microorganisms consume plant-available nitrogen (ammonium and nitrate) while decomposing the plant material, reducing the amount available for the corn crop in the soil.

A MANURE TREATMENT YOU CAN ACTUALLY GET PUMPED ABOUT

Pit-king

MANURE DIGESTANT PRODUCT

“...had results in the first week of application. The manure smelled different and was very easy to pump.” -- East Wisconsin dairy

“The manure hauler commented he never had a pit of manure that was pumpable without agitation.” -- East Pennsylvania dairy “The smell and the air quality has improved dramatically.” -- Northeast Iowa dairy

(800) 435-9560 AGRIKING.COM

Nitrogen adjustments to manure N credit book values

Cover crop biomass (lbs./ac) Estimated N uptake (lbs./ac) Amount to adjust manure N credit (lbs./ac)

<1,000

1,000 to 2,000 <25

25 to 45 No adjustments needed

Subtract 35 lbs./ac from manure N credit if winter rye was used*

>2,000 >50 Do not take any manure N credit**

*There was no clear effect when winterkilled cover crops were used based on Wisconsin research. **This recommendation applies to manure N applications up to 100 lbs./ac of available N. (Adapted from Ruark et al., 2019)

The more winter rye biomass there is, the more immobilization that can occur.

It’s important to note that the findings reported here are for late summer and early fall manure applications. There are still many aspects of cover crop use with manure that need to be fully explored, such as timing of manure application (in late fall or spring).

Cover crops and corn yield

Similar to our findings with nitrogen, risk of corn yield loss occurred when cover crop biomass exceeded 1,000 lbs./ ac. The biggest effects were observed when winter rye exceeded 2,000 lbs./ ac. For the most part, yield reductions were less than 10 bu/ac, and there were no observable nutrient deficiencies in the corn crop. Our findings are not unique, as others in the Midwest have found similar results.

In contrast, cover crop trials by the Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) have shown yield reductions to be rare, occurring in only two of 29 site years

COVER CROP RECOMMENDATIONS

Here are tips for keeping biomass low and for managing corn following cover crops: 1. If new to cover cropping, consider starting with spring barley or oats (covers that will winterkill in cold climates).

2. Keep seeding rates low for covers that survive the winter (such as 60 lbs./ac or less for winter rye). 3. Wait 10 to 14 days between termination of winter rye and corn planting. 4. Utilize a starter fertilizer that contains nitrogen. 5. Use row clear attachments on planters to increase soil warming around the seed.

6. Split apply N fertilizer, or at least avoid having all of the nitrogen applied in-season. The following are considerations for when you get more than 2,000 lbs./ac of winter rye: 1. If a lot of biomass has already been produced during a warm fall, consider a fall termination to avoid excessive biomass in the spring. 2. Terminate the winter rye as early in the spring as possible and make between 2011 and 2019. (The report can be found at www.practicalfarmers.org.) These studies by PFI were conducted with cooperating farmers on their fields. Collectively, this indicates that there is some potential risk to corn yield when winter rye biomass gets too high, but experience with cover crops can reduce the overall risk of yield loss.

Grass cover crops take up nitrogen from the manure that would have likely leached out of the root zone over winter and spring before planting. However, it does appear to tap into the nitrogen that would typically be available for that next corn crop. The trick for farmers is to grow enough cover crop biomass for good erosion control but not grow too much as to tie up nitrogen. See the sidebar for recommendations. ■

The author is a professor in the department of soil science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

fields with an abundance of winter rye biomass top priority in the spring. 3. Consider harvesting the winter rye as a winter silage crop. This would also be beneficial from a nutrient management planning perspective, as the nutrients from the fall manure application would be applied to this winter silage crop. If interested in this option, it will also be important to follow all herbicide rules, as some applications can prevent the winter rye from being fed. 4. If you want to avoid risk, consider planting soybeans instead of corn.

PLAN FOR NEXT YEAR’S NITROGEN NEEDS

Afield’s nitrogen needs vary from year to year. In a recent University of Nebraska Extension Crop Watch article, extension specialists explained that this need is partially dependent on the previous year’s weather conditions, previous crop nitrogen uptake and yield, and postharvest residual soil nitrogen.

The authors shared that when a growing season is drier than normal, it may limit downward movement of nitrogen (N) in the soil profile, nitrate leaching loss, crop nitrogen uptake, and crop yield. A reduction in yield could leave more residual N in the soil; a soil sample taken at a depth of 2 to 3 feet in the fall or spring would confirm this.

Timing of N application is critical for crop yield, N use efficiency, economic return, and N losses into the environment. Since precipitation is unpredictable, the potential for N loss is present during the fall, winter, and early spring. For this reason, the authors said that spring soil sampling

The number of anaerobic digesters on farms continues to expand, growing tenfold between 2000 and 2020 (see graph below). As of this year, there are 255 anaerobic digesters in operation and 33 more under construction, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Ag STAR program. Of those farms operating digesters, 205 have dairy cattle, 44 raise hogs, eight have beef cattle, and seven raise poultry. Some digesters accept manure from more than one species, which is why this total exceeds 255. and split N application (preplanting and in-season) is the best strategy. However, if applying N in the fall, consider the following practices to avoid over application and N loss. 1. Sample soil at 2 or 3 feet deep to determine residual nitrate-N to be credited in nitrogen rate calculations. 2. Apply fertilizer N or manure when soil temperature is below 50°F at a 4-inch soil depth. 3. Apply anhydrous ammonia instead of other N fertilizers. 4. Limit fall application of N to silt loams, silty clay loams, and finer textured soils. 5. Avoid fall application on wet or flood-prone soils. 6. Consider applying part of the N in the fall and the remainder during the growing season. 7. Following University of Nebraska-Lincoln recommendations, plan to apply 5% more fertilizer-N in the fall compared to spring application to compensate for

FARMS STEADILY ADDING DIGESTERS

potential losses.

Anaerobic digesters on U.S. livestock farms

Number of operating digesters 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 -50

00 02 04 06 08 10 ■ Under construction ■ Newly operational

12 14 16 ■ Operational Source: AgSTAR Livestock Anaerobic Digester Database 18 20

■ Shut down

All photos: Abby Bauer Litter and used manure are composted in windrows; some of it is used as bedding in the barns. The remainder is stacked in a manure shed and then land applied.

by Abby Bauer, Managing Editor

at Stutzman’s original career plan in public relations and sports media didn’t exactly include agriculture, but growth opportunities and technology drew him back to the farm he grew up on.

“I always enjoyed the business aspect of farming,” Mat said. “As technology became more prevalent in agriculture, that got my attention. The tech side played a major role for me.”

Mat’s grandfather moved to Constantine, Mich., in 1961 and started crop farming there. Mat’s parents, Albert and Sarah, followed suit, and until 2012, the Stutzmans were strictly grain farmers running 3,000 crop acres. At that point, Mat and his three siblings had all returned to the farm, and the ability to incorporate the third generation is what pushed them to diversify.

They considered other forms of livestock before partnering with Miller Poultry, a poultry processor headquartered in Goshen, Ind. Miller Poultry was looking to expand its business and needed more farms to raise birds, and the Stutzmans quickly became interested.

For the love of manure

They started out by building two broiler barns in 2013 to “dip our toe in the water and see what it was like,” Mat said. They quickly saw the benefits poultry manure provided their crop fields, along with the opportunity to provide more job opportunities on the farm.

In fact, poultry litter, not meat production, is really what pulled the Stutzmans to broiler raising. “We love the manure. That’s the reason we got into poultry,” Mat said. “Our number one goal was to produce manure for application.”

That interest in manure’s value started with Albert. When Albert took over the farm from his dad, he focused on nutrient management, started to plant cover crops, and instituted other environmental friendly farming practices. Albert also worked for a local dairy farm as a supervisor, and their anaerobic digester that generated power for the dairy intrigued him. “My dad was always interested in energy production,” Mat said. “We started looking at those concepts.”

While anaerobic digestion wasn’t a great fit for their farm, they quickly saw the litter provided tremendous value when land applied. “High-quality nutrients and everything you get from manure, that’s really why we expanded the poultry farm,” Mat said.

A year after their initial barns went up, they built two more, and then four more the year after that. Then, in 2017, Mat’s sister and her husband, Lynette and Tim Carpenter, built a four barn breeder egg facility. There they produce fertilized eggs that are picked up by Miller to be hatched at their facility. Last year, the Stutzmans built another breeder egg facility 1.5 miles from the home farm.

Capturing the sun

Mat’s brothers have since moved on from the operation, so today he farms with his sister, his brother-in-law (who manages the crop side of their farm), and his parents. Albert’s interest level in renewable energy remained high, so they continued to look for ways

Albert and Mat Stutzman handle the dayto-day operations on their broiler farm, where they have up to 320,000 broilers on-site at one time.

to advance the farm in that area. Although it appeared too cost prohibitive at first, the Stutzmans found the right contracts with the right people and some grants that allowed them to install 870 solar panels on their farm this year.

“It was still a large financial invest-

ment of ours,” explained Mat, “but we see two positive benefits. For one, our electrical bill by the end of this year should be down to $0, so there is a financial aspect to it. We are also cutting down on our electrical usage and producing energy in a way that is much more environmentally friendly.”

The solar panels will generate 425,000 kilowatt hours per year, or enough electricity to power 40 homes. All energy used in barns is being produced by the solar panels. Some of the harnessed energy is sold back to the power company; the rest is banked for use on the farm overnight or on nonproductive days when the panels are not capturing enough sunlight.

“It will be well down the road before we’ll see some financial return, but the reason behind the solar panels was that when people pull in to the farm, we want them to see the steps we are taking to be environmentally friendly in our farming practices,” Mat said, reaffirming their commitment to sustainability.

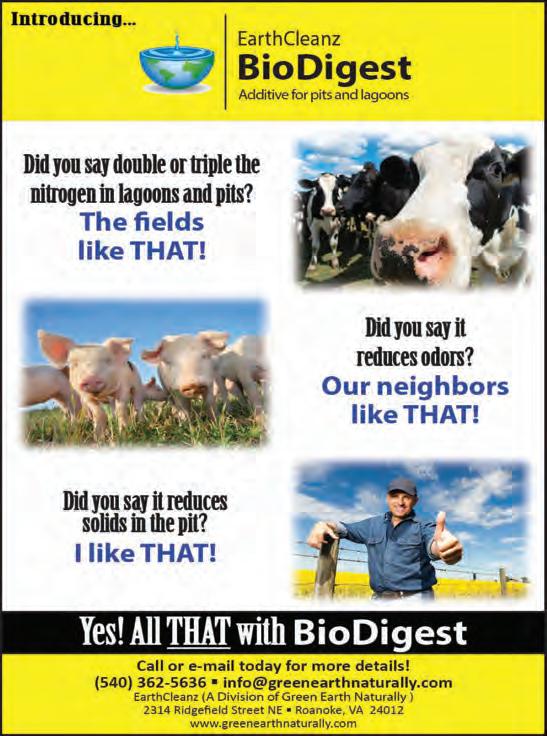

In the barns

Powered by the sun, each of the broiler barns is 60 feet wide by 600 feet long and can house 40,000 birds. When at full capacity, the Stutzmans are raising 320,000 birds on-site at a time. Miller Poultry brings the chicks from their hatchery when they are one day old, and the Stutzmans raise the birds for about 41 days, or until they are 5.2 pounds. Miller formulates and

A total of 870 solar panels harness energy from the sun, producing enough power to run the farm and sell some to the electric company. delivers the feed for the broilers, which changes as they grow. The Stutzmans’ farm is not certified organic, but they do raise their broilers without the use of antibiotics.

A new requirement of the Global Animal Partnership (G.A.P.) standards, which farms growing for Miller Poultry abide by, is incorporating windows in all barns to allow natural light. “The sun is good for you,” Mat said. “We have seen nothing but health benefits from it, and we get a lot better yield out of the birds.”

They also maintain a very consistent environment inside the barns. In the winter, this includes running furnaces to provide heat. For summer, fans and cooling walls are used to bring the temperature down and ventilate the barns. The cooling walls contain a material like cardboard and have cold water running through them.

“We try to make the birds as comfortable as possible,” Mat said. “A happy chicken is a healthy chicken.”

To make sure birds get off to a good start, they lower the feed and water trays so the 1-day-old chicks can easily access them, and they use Christmas lights to attract chicks to the water. Water intake is something that they monitor very closely, because Mat said, “It is often the first indicator that something is wrong.” They also drop a curtain halfway through the barn for the first 11 days to keep the chicks closer to food and water and in a more secure environment.

They have added different enrichments to the barns to enhance animal well-being. This includes perches and buckets with both ends cut off to provide areas for privacy when birds want it.

Once a barn full of broilers has grown and left the farm, the barn is cleaned out. The goal is to have a 3-inch layer of bedding on the ground when a new group of birds is placed in the barn, so the Stutzmans remove compost as necessary to reach that point. Sometimes they use a piece of equipment called a housekeeper, which Mat likened to a potato digger. It shakes up the litter, removing larger wet chunks while leaving behind the drier used shavings.

What lies beneath

The remaining used bedding and manure is pushed into windrows, and over the course of 14 days, the windrows are rolled two times to make sure the proper temperature of 140°F is maintained for composting. “That is key for antibiotic free,” Mat said. “Composting kills off the negative bacteria.”

Once composting is complete, the litter is leveled out and a layer of fresh shavings is placed on the top. Mat explained that for chicks, the litter is their immune system’s “lifeblood.” He said, “If they didn’t have bacteria that is in the used litter, the mortality rate would spike.” Not being able to use antibiotics can be a challenge, especially in the very young chicks. “Biosecurity is really, really big,” Mat said. “It is your main line of defense.”

The used litter and manure that is removed from the broiler houses is placed under an open-sided stack barn. Here the litter and manure are further composted until it’s used for land application. The Stutzmans test both the soil and the manure to make sure they are applying the correct amount on their

fields, which they use to grow mostly seed corn and soybeans.

While they use some of the litter themselves, at this point, a majority is sold to other farms in the area. They have found a market and great demand for their product; the potato growers especially love it, Mat said. They currently have a waiting list for crop farmers wanting to purchase their composted manure.

The future of farming

While Mat’s four children are still young, some of his nieces and nephews are starting to show interest in joining the farm. The Stutzmans’ philosophy requires them to work somewhere else for two years before returning to the family business.

“Farming is so advanced now. The amount of business and tech involved, nutrient management, planning — it’s grown to such a high level,” Mat said. This requires more education, but it also creates more opportunities in different areas. And much of the thoughtful planning and practices the Stutzmans have put into place are in hopes that their farm can carry on for three more generations.

This includes the farm’s location, which they chose very carefully before building their first barns. With land spread over three counties, they selected this spot as there are no nearby neighbors. Using proper air control management, Mat said there are seldom odor issues anyway, but they remain committed to public perception and showing consumers what they do.

“We are genuine about what we do, how we care for our animals, and the way we care for the land,” Mat shared. “I think that’s very important for agriculture right now, finding ways to show our consumers and people not on a farm the positives we are doing.”

The Stutzmans feel their addition of solar power, which was the first installation on a Michigan poultry farm, was a prime example of how production agriculturalists can connect with consumers in a positive way. “We are really going the extra step to show we are looking at sustainability and looking for environmentally friendly ways to produce proteins, fruits, and vegetables,” Mat said.

“We take pride in what we do,” Albert added.

Their family remains committed to sustainable agriculture practices, mixed with technology that can help them raise healthier animals and grow better crops. For Mat, he is energized by the future potential of their farm. ■

Service is #1 here at CentriTEK Industrial Centrifuge Specialists. Along with the high quality service on all brands of centrifuges, CentriTEK supplies a line of decanter centrifuges and systems which are Made in the USA and well suited to handle the requirements for all sizes of dairy farms looking to improve their overall manure management processes.

Fiber Recovery for Bedding

Nutrient Recovery and Phosphorous Reduc on

Reclama on and Reuse of Water for Flushing

High Solids Removal to Reduce Loads on Lagoons

CENTRITEK IS PROUDLY REPRESENTING TRIDENT PROCESSES IN CALIFORNIA

FOR COMPLETE AND TURNKEY MANURE MANAGEMENT PROCESSES