HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

Yonia Fain: Remembrance

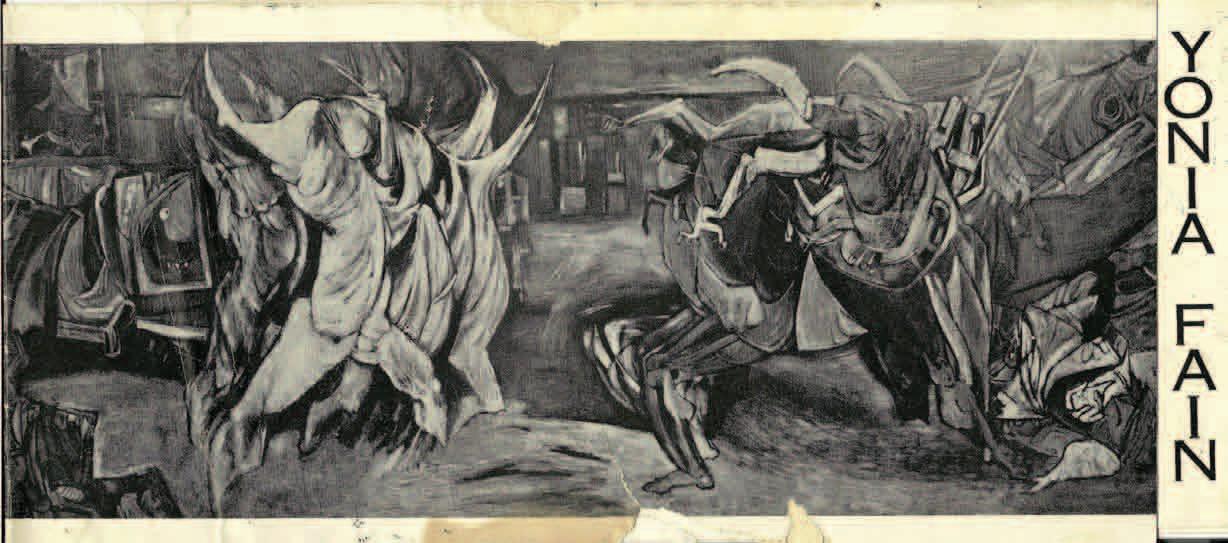

Front cover credit: Yonia Fain, Holocaust, n.d. (detail), oil on linen, 79.5 in. x 132.25 in. Courtesy of the artist.

© 2012 Hofstra University Museum

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

Yonia Fain: Remembrance

Exhibition dates: April 19-August 3, 2012

Emily Lowe Gallery

Curated by Karen T. Albert

Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections Hofstra University Museum

Funding for this exhibition and catalog has been provided by: Hofstra University New York State Council on the Arts Tilles Family

Yonia Fain: The Painter of History

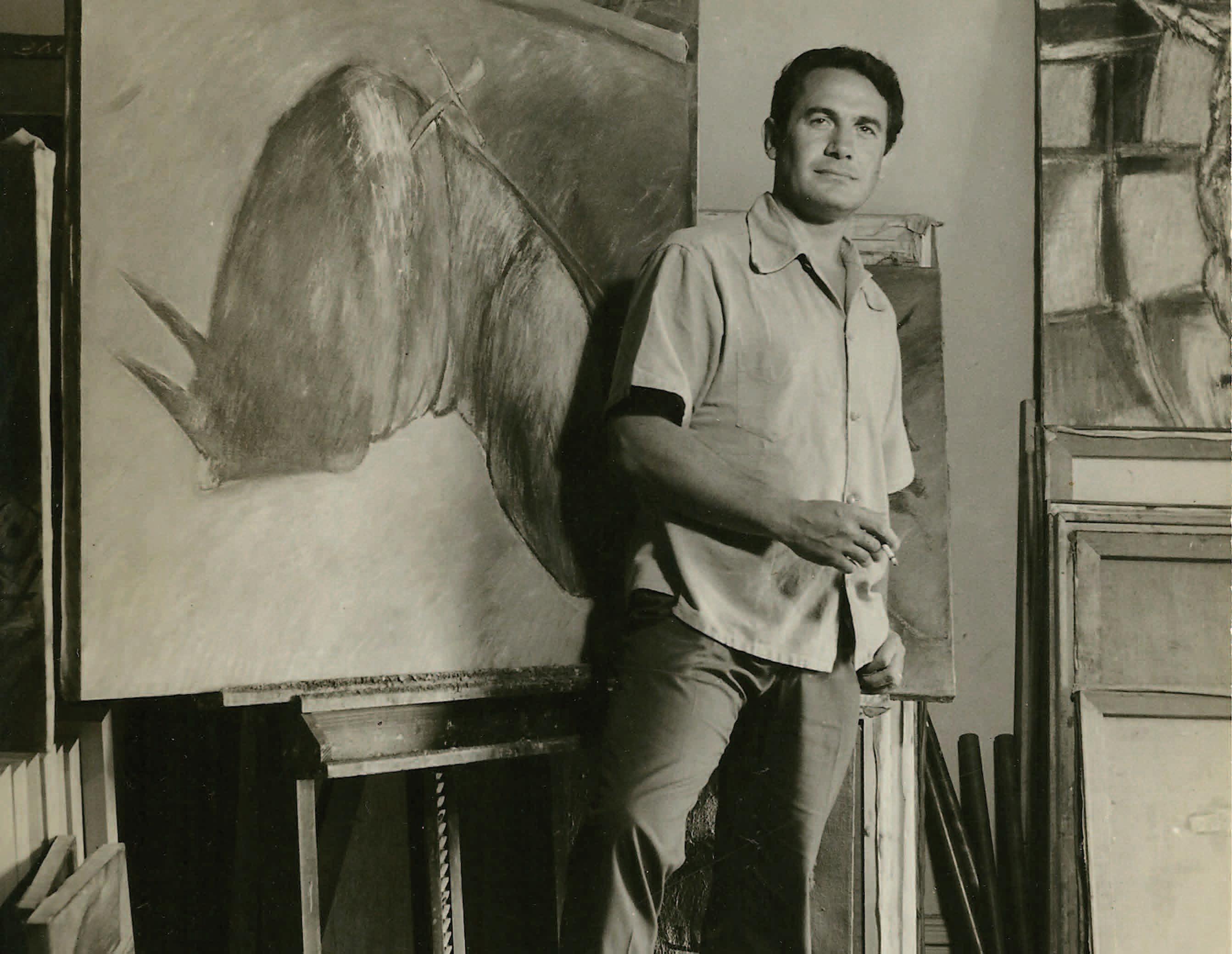

It has been my honor and good fortune to have become well acquainted with the artist and poet Yonia Fain. Over the past five years, in numerous conversations and visits with the artist, his magnetic and charismatic presence along with his soulful and ever-passionate voice have taken me on an incredible journey filled with poignancy and pain, beauty and brutality – a journey back in time to the Holocaust – to a place when lives that held so much passion, brilliance, talent and promise were abruptly ended.

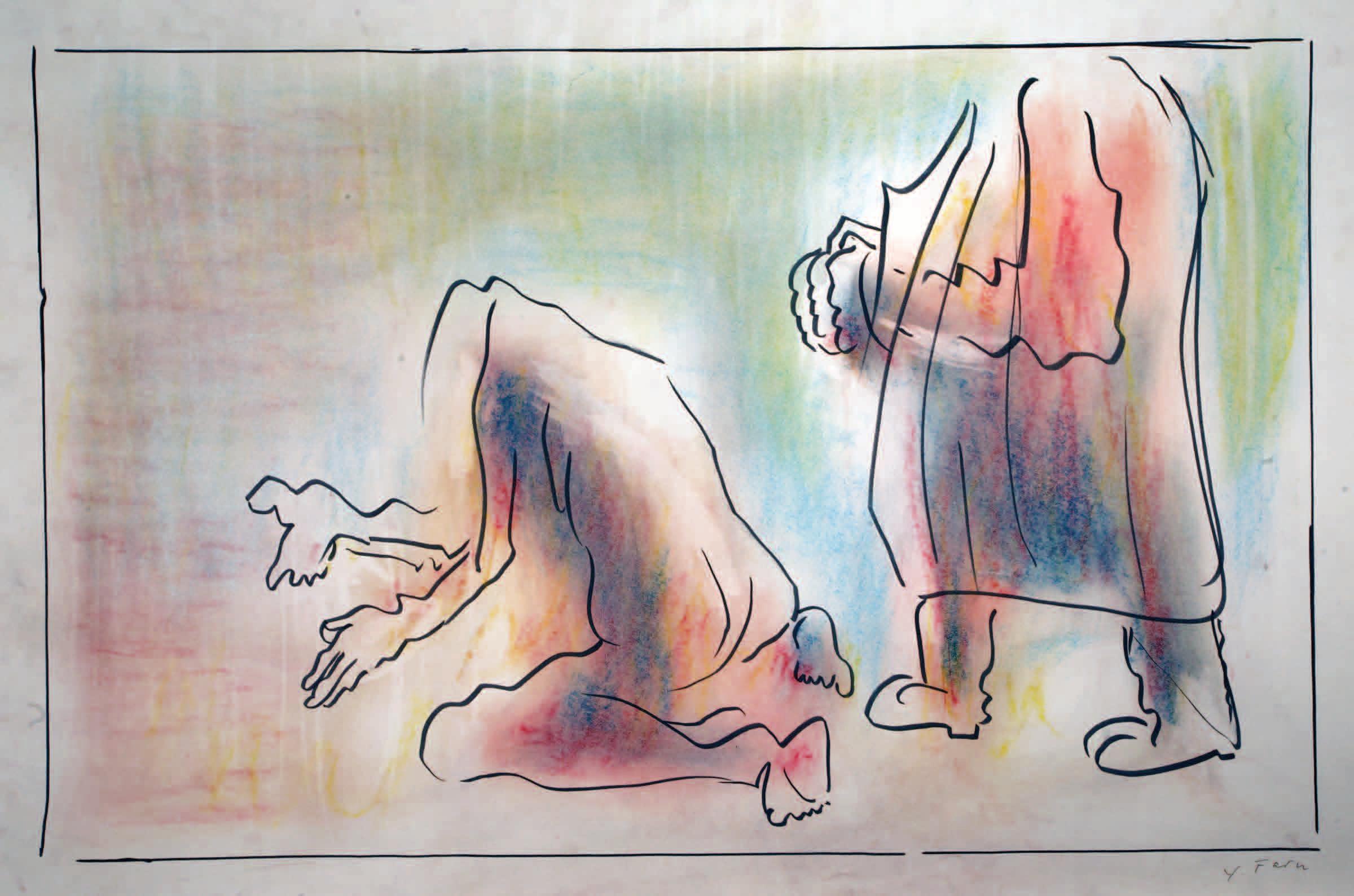

I have also had the immense privilege, along with my colleagues, of studying Yonia Fain’s art, his often larger-than-life canvases that convey the atrocities of war while simultaneously offering hope and the affirmation of life. Yonia’s paintings and his thousands upon thousands of works on paper are, in turn, exquisite as well as inordinately painful. Through his masterful use of line, his conveyance of the human form, his choice of color, and his brushstrokes, the viewer becomes caught within a transformed reality that ignites the imagination, letting us know we are in the presence of a singular artistic voice, a voice that conveys “history.”

As a peripatetic artist, with a commitment to his art and poetry as well as to assuring that the world does not forget, and in works created as recently as 2012, Yonia continues to pay tribute to life’s promise, which, through forces of evil, was snuffed out for millions of human beings. I am in awe of the life force that defines Yonia Fain – his paintings, drawings, works on paper, and his poet’s voice, a voice that emerged with strength and vibrancy from a life filled, from his earliest days of childhood, with fear, pogroms, loss, change, challenge, triumph and wisdom.

I am not alone in my admiration for the artist. Hofstra University’s long and significant relationship with Yonia Fain began in 1971, when at the urging of the late Dr. Robert Myron, former chair for the Department of Fine Arts, Yonia became a professor of art history and the philosophy of art, teaching at Hofstra until his retirement in 1985

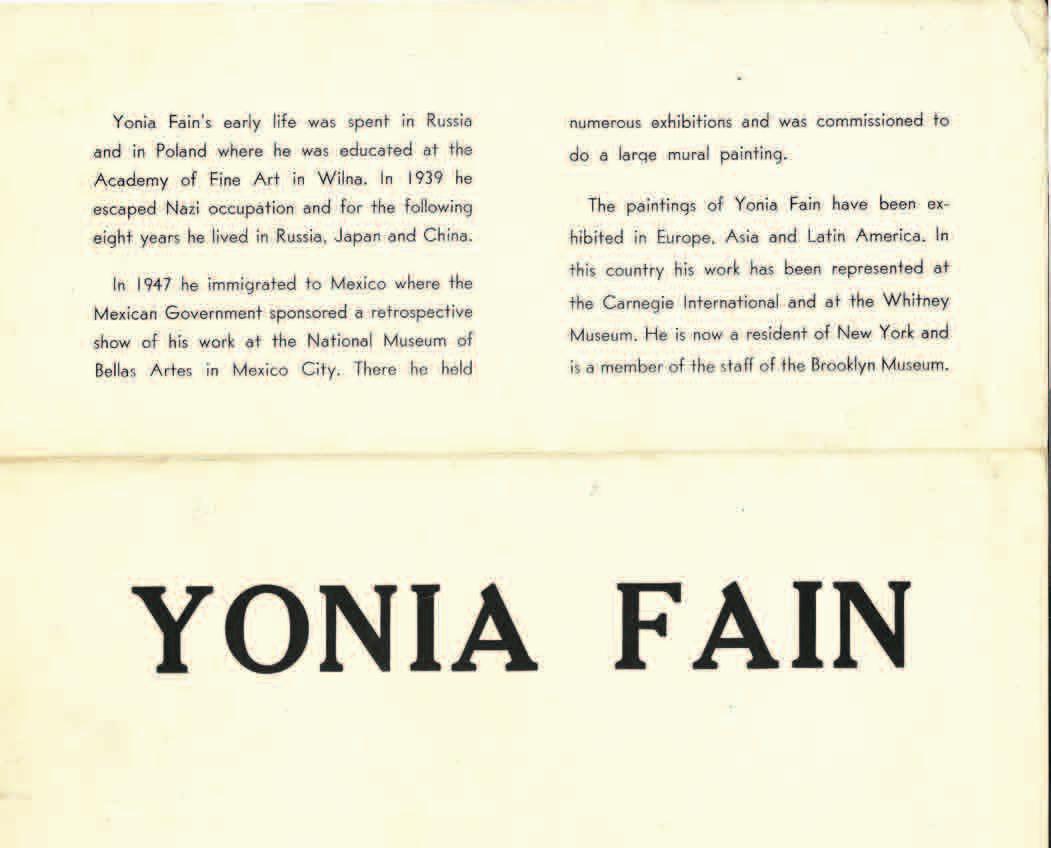

Yonia, an internationally acclaimed artist and poet, is a first-hand witness to historic events of the early and mid-20th century in Europe Born in Russia in 1913, he moved as a young boy to Vilna (Vilnius), Poland, where his father had been offered a position as a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Vilnius. During his years in Vilna, Yonia studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, receiving B.A. and M.F.A. degrees.

In 1939, when the Soviets invaded, Yonia and his first wife fled from Vilna to Warsaw, but then as the Nazis invaded Warsaw, during the Fains’ attempt to leave the country, Yonia was captured and detained by Soviet authorities. Yonia was to be conscripted into the Soviet army as a propaganda artist, but just before reporting for duty he learned from a highly placed friend that his life was in danger, and he was urged

to escape. The Fains were able to obtain falsified Japanese transit visas, and traveling through Siberia they escaped to Japan. The Japanese had captured Shanghai, China, just prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and it was to this city that the Fains were transported from Japan They spent the remainder of World War II in the Shanghai Ghetto for Jewish refugees. During those years, Yonia earned his living painting portraits of soldiers and their families.

After the war ended, Yonia felt compelled to paint “history,” but did not wish to do so in a Europe that saw the annihilation of his family and friends, a place he no longer could consider home

exhibits at the Albright-Knox Gallery, the Brooklyn Museum, the Butler Institute of American Art, the Carnegie Art Institute, the Chrysler Art Museum, the National Holocaust Museum, Oxford University, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others In 2007 an exhibit of his work took place at the London Jewish Cultural Centre, and in 2008 the Hofstra University Museum offered A Painter’s Witness to History: Recent Work by Yonia Fain, featuring mixed media works on paper created by the artist during that year.

In addition to his work as a visual artist, Yonia Fain is an award-winning Yiddish poet, who has won international acclaim with his books that include A Gallow Under the Stars, Beloved Strangers, New York Addresses, and The Fifth Season He long served as president of the Yiddish Pen Society, and his poetry has been honored by the State of Israel.

– Yonia Fain, 1957

Whenever I look back into the past, a cemetery of immense proportions arises before my eyes. Here rest my best friends They perished in torn lands and burning cities, fallen as fighters in anti-Nazi undergrounds or as political prisoners in Soviet jails. I always see them as rebels and dreamers who did not recognize the art of compromise, acceptance or indifference

Having read about and seen the work of the renowned muralist Diego Rivera and the transformative impact that his mural art was having upon society, Yonia set his mind to relocating to Mexico. During his years in Mexico (1946-1953), Yonia was a professor of art at the University of Mexico, and he worked closely with Diego Rivera, learning the artistry of mural painting. Rivera also championed Yonia’s work by mounting several exhibitions and writing the catalog essays. During those years, as Yonia listened to the voices of the many refugees from Europe who had relocated in Mexico, his work reflected their commonality of history and experience. In 1954, at the urging of artist and friend Rufino Tamayo, Yonia moved his family to New York City, the center of the contemporary art world at that time Tamayo and his wife arranged a connection for Yonia with several galleries, including the La Monde Gallery in New York City, as well as help him secure a teaching position at the Brooklyn Museum, where he had a 14-year tenure with colleagues such as Max Beckmann. From 1964 to 1970, he taught art history at New York University until he arrived at Hofstra

His prolific life as an artist continued throughout the years, and his work has been the subject of numerous one-man shows as well as being included in

This exhibition, Yonia Fain: Remembrance, features a retrospective look at works by the artist created between 1959 and the present. The catalog includes full-color reproductions of his works, as well as an essay and timeline, which provide a strong historical and artistic context for the artist authored by Dr. Kenneth Wayne, art historian and deputy director for curatorial affairs at The Noguchi Museum. Hofstra University Museum’s associate director of exhibitions and collections and curator of this exhibition, Karen T. Albert, provides us with an insight into the painted dome and wall mural Vision of Ezekiel created by Yonia at the Memorial Chapel, Panteon Israelita (Cementerio Ashkenazi), Mexico City, Mexico.

Yonia’s life, his poetry and his art form an important legacy for current and future generations. Yonia’s experiences and creative output span most of the 20th century and more than a decade into the 21st century; his clear voice speaks to us through his powerfully rendered works with messages of a time that must never be forgotten; his message to us is “remember, remember, remember. …” He urges us to do so with a sense of hope that must always endure and with a commitment to our fellow man that we can only strive to emulate.

Beth E. Levinthal Executive Director, Hofstra University Museum

Ceiling dome painting

Wall mural

Yonia Fain: Wall Mural and Ceiling Dome Painting for the Memorial Chapel, Panteon Israelita, Cementerio Ashkenazi, Mexico City

While living in The Shanghai Ghetto during World War II, Fain learned of the work of the Mexican muralists who, after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), painted public buildings with murals that reflected the social and political events and ideas of the time. He admired the work of Diego Rivera in particular. Rivera, one of the most important figures in the Mexican mural movement, won international acclaim for his mural works that promoted social justice, political causes and venerated the native heritage of Mexico. Fain felt a common bond with Rivera’s work and purpose – as a witness to history himself, Fain was seeking to express his experiences and those of others through his art.

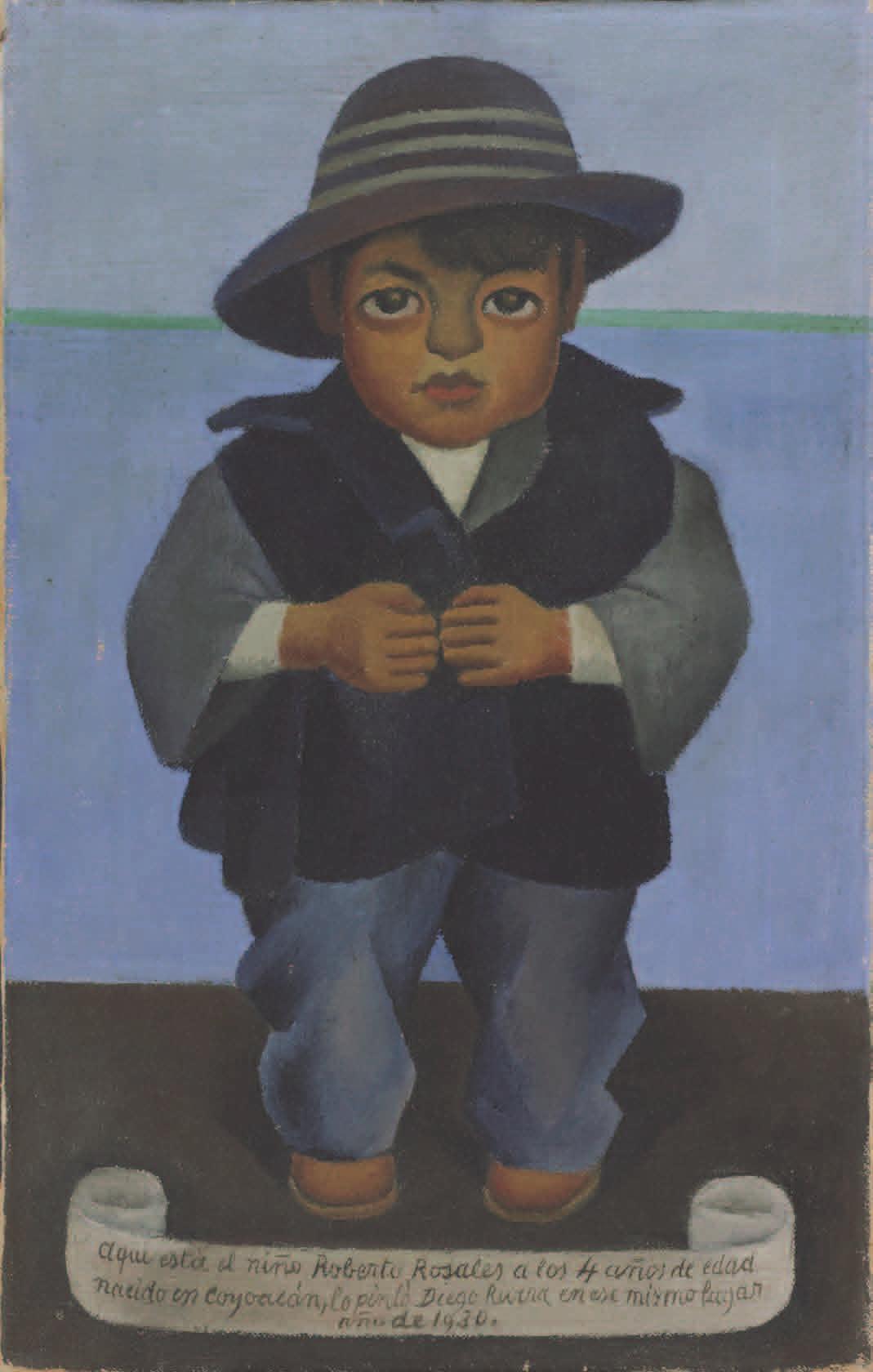

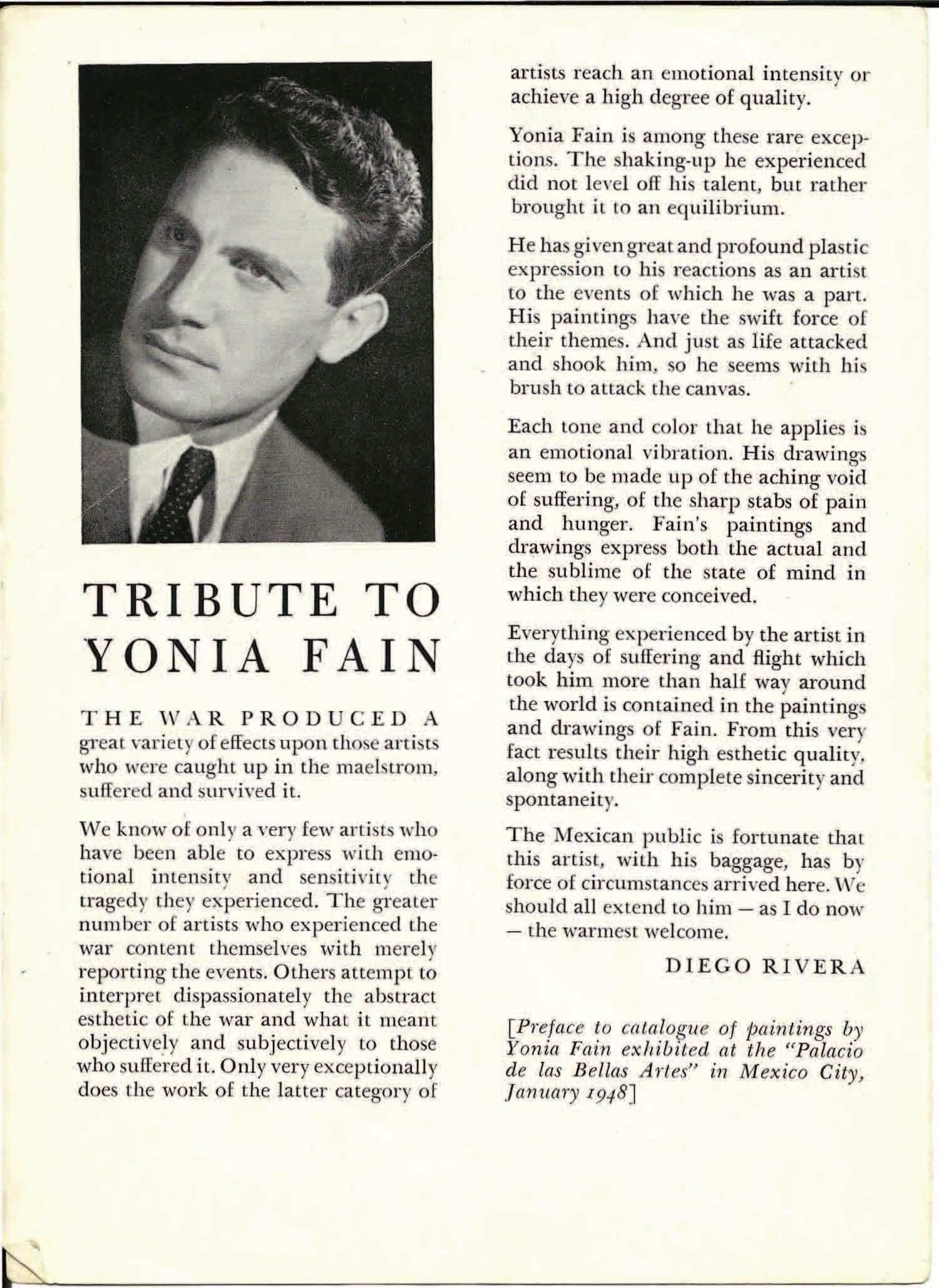

When World War II ended, friends encouraged Fain to move to Mexico, and upon meeting Diego Rivera, who had already been impressed by examples of Fain’s work, Rivera embraced Fain as an equal and felt a strong connection with him. Fain has noted that he and Rivera spoke Russian together, not English (Diego Rivera, as history conveys, had along with his wife, Frida Kahlo, befriended the communist leader Leon Trotsky after he received political asylum in Mexico from Joseph Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union during the late 1930s. It was in 1940, that Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico). Rivera was instrumental in arranging for Fain’s exhibition at the Palacio de las Bellas Artes in 1948, for which Rivera wrote a strongly supportive and enthusiastic statement about the artist for the exhibition brochure.

While living in Mexico City (1947-1953), Fain completed a wall mural and ceiling dome painting for the Memorial Chapel, Panteon Israelita, Cementerio Ashkenazi (Jewish Cemetery). The chapel stands as a monument to the “memory of the six million of our fellow men and women, old and young, who perished during World War II.” The painted dome illustrates the biblical story of the vision of Ezekiel in which under the Lord’s command the valley of bones comes together and returns to life forming a great army Ezekiel stands with a raised arm and the figures around him are in various stages of regeneration: bones, muscles, skin and entire bodies can be seen The images of death and killing are juxtaposed with ones of revival and new life. These themes of destruction and hope have continued to inform Fain’s work throughout his life. Fain’s mural on the wall of the Memorial Chapel depicts an uprising of citizens in a city; the people are marching , struggling and fighting for their lives This is also a recurrent theme in Fain’s work

Karen T. Albert Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections, Hofstra University Museum

Yonia Fain: An Artist of the Holocaust

Yonia Fain’s world view and artistic approach were transformed during the years of the Holocaust. The fighting, dislocation, Diaspora and the pervasive human tragedy that he witnessed all led him to create an art that is apocalyptic, emotional and heartfelt. His emphasis is on human figures and animals in turmoil – agitated and desperate – his art is devoted to the human condition and to the human experience.

Fain was born in Kamyanets-Podolsky in the Ukraine (then a part of Russia), near the border with Romania, on June 6, 1913, on the eve of the Russian revolution. He grew up during a civil war,1 the first of many periods of political rebellion and turmoil that he would experience. Around age 6, he moved with his family to Vilnius, often referred to as Vilna, (which at that time was a part of Poland before returning to Lithuanian control), for his father to become a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Vilnius. Yonia Fain studied at the Vilnius Art Academy, which was part of the University, receiving a classical art education, including drawing after casts of Greek sculptures. Like most other Jews there at the time, he spoke Russian, Polish, and, above all, Yiddish. When Yonia Fain lived there, Vilnius, which was known as “the Jerusalem of the North,” was a rich center of Jewish life with 100 synagogues, six daily Jewish newspapers, and a large number of Jewish schools, theaters, guilds and political groups.

Other artists passed through Vilnius, underscoring its important role as a cultural center. The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz went to high school there from 1906 to 1909, before heading to Paris. In his memoirs Lipchitz wrote that he learned about Paris’ importance to artists while in Vilnius.2 The painter Chaim Soutine studied at the Vilnius Art Academy from 1910 to 1913, before moving to Paris and achieving international fame. Fain, who received B.A. and M.F.A. degrees from the same Academy, noted that Chaim Soutine is among the artists whose work he most admires (others are Archipenko, Leonardo DaVinci, and Diego Rivera).

Fain and his first wife, Nuta, fled Vilnius for Warsaw in 1939, originally hoping to go to Paris. His decision to leave Vilnius was prophetic as 94 percent of the 240,000 Jews from this region were killed during WWII. Somehow, Fain and his wife were able to escape the Nazis, who invaded Poland that year, and the Russians who sought to imprison them. He learned then that the human spirit was “stronger than Hitler or Stalin.”

In June 1940, he and his wife obtained Japanese transit visas from the now-famous Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara who worked in the Japanese consulate in wartime Lithuania (occupied by Russia at the time), in a town called Kaunas.3 Sugihara issued 2,000 exit visas to Jews fleeing Eastern Europe and has been honored at Yad Vashem in Israel as Righteous Among Nations for his heroic acts in saving Jews. The Jews saved by Sugihara traveled to Japan and then to Japanese-controlled Shanghai in China.

1 Biographical information was obtained directly from Yonia Fain during conversations in May and November 2011, as well as from printed material

2 Jacques Lipchitz, My Life in Sculpture, with H.H. Arnason. New York: The Viking Press, 1972, p. 3

3The visas were not in their names, according to Yonia Fain, having come from Sugihara indirectly via friends There are books and films on Sugihara and his heroic acts

Shanghai had an international community since 1842, following the end of the first opium war, when the Treaty of Nanking was ratified and the British established a colony there. By 1862, the French and Americans joined them, and the Shanghai International Settlement was formed. Western law ruled in this section of town. The first wave of Jews came in the late 19th century, from Baghdad, for trading and business purposes and established a wealthy community there. The second wave, less affluent, arrived in 1917 from Russia, fleeing the revolution. Starting in 1933, the third wave of Jewish immigrants came in reaction to the rise of the Nazi regime and anti-Semitic laws adopted in Germany. Following the Sino-Japanese War of 1937, the Japanese oversaw the Settlement and Shanghai generally. Fain and his wife were part of this third Jewish wave, arriving in fall 1941.

Fain and his wife lived first in the International Settlement, then in the Ghetto that was established there in 1943, which had approximately 18,000 Jews, all living in an area about three-quarters of a mile square in size.4 The Fains lived in Shanghai from 1941 to 1945. (Their actual original destination was Curaçao in the Caribbean, which was part of Holland, but the Japanese invaded Pearl Harbor a few weeks after they arrived and joined forces with the Axis powers, which kept the Fains in Shanghai.) Jews fled to Shanghai because it did not require visas and did not have quotas for Jews, unlike most other places in the world, which rejected Jews (including the United States). Its already-existent Jewish community would have been a bonus. Shanghai was a major, international and open port that accepted refugees.

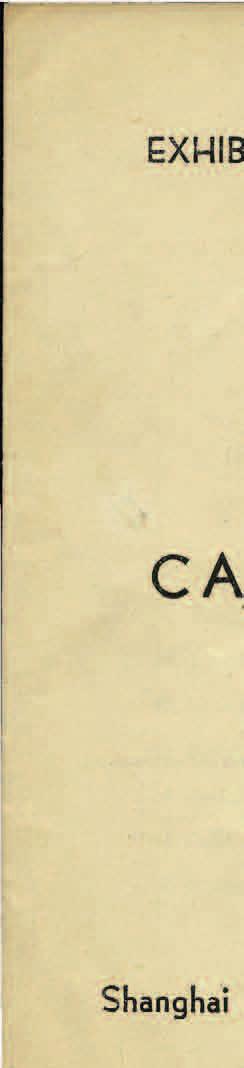

Fain, whose poetry provides vivid images of the despair experienced during this period, said that, despite the strife, life in the Shanghai Ghetto was nothing like life in the ghettoes in Europe. (Others recalled the hunger, humidity, heat and squalor of Shanghai.)5 He added that the Japanese treated Jews fairly well in comparison to the poor way that they treated the Chinese. Fain painted portraits in Shanghai to make a living and had exhibitions of his work there, including one at the Jewish Club from May 31 to June 15, 1942, that featured 53 works (oils, watercolors, drawings) and was accompanied by an un-illustrated catalogue. There were different themes to the exhibition: Japanese Motives; Bible Motives; Jewish Motives; Terrible Times. Fain was already writing serious poetry by this time and penned “A Poem About Shanghai Ghetto” in 1945.6

A very rich Jewish life developed in the Shanghai Ghetto with Jewish newspapers, restaurants, sport clubs, theaters, schools and synagogues flourishing

Central and South America is where some Vilnius Jews ended up after getting visas from Sugihara and passing through Japan and the Shanghai Ghetto. Fain learned that some of his friends from Vilnius were living in Mexico, including one named Nadel. The wife of Nadel was modeling for Diego Rivera and showed some of Fain’s drawings to the great Mexican artist who was deeply impressed with Fain’s talent. Given his old ties, and encouragement from Diego Rivera, Fain moved to Mexico City in 1946. Soon after Fain’s arrival, Diego Rivera arrived at his door, seeking him out. He worked with Rivera for seven years. Fain quickly emerged as an art star, having a one-person exhibition with 74 works at the Palace of Fine Arts in January 1948, which was accompanied by a catalogue in which Diego Rivera wrote the preface titled “Tribute to Yonia Fain.” Here is an excerpt:

The War produced a great variety of effects upon those artists who were caught up in the maelstrom, suffered and survived it. … Each tone and color that [Fain] applies is an emotional vibration. His drawings seem to be made up of the aching void of suffering of the sharp stabs of pain and hunger. Fain’s paintings and drawings express both the actual and the sublime of the state of mind in which they were conceived.

It is easy to see why Diego Rivera had an affinity for Yonia Fain’s art given the strong element of social injustice conveyed in both artists’ work. Each is concerned with humanity and man’s plight in society. Another fervent admirer of Fain’s was the artist Rufino Tamayo who wrote an equally eloquent tribute to the artist for an exhibit of his work in New York City:

This young painter’s poetical force captivated me from the very first moment I saw his work. He comes after a prolonged stay in my country to offer this demanding but cordial public the fruits of his careful search. Like all men of value, he comes modestly, but at the same time, sure of his destiny to which all of his strength has been totally dedicated. His exhibition is taking place here where, fortunately, everything which has merit eventually finds recognition. I am sure that the high quality of his work, and also his individuality, will quickly win him innumerable friends.

4 The Shanghai Ghetto was established on May 18, 1943, according to a proclamation first announcing its formation on February 18, 1943. After the war, it was learned that the Ghetto was instigated by the German authorities who pressured the Japanese to establish it

5 Ernest G. Heppner, Shanghai Refuge: A memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995, pp. 112-113

6 Under the name Yoni Fayn. For more on this, see Irene Eber, ed., Voices from Shanghai: Jewish Exiles in Wartime China. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008

7

A very refined artist, Tamayo was also interested in abstracted forms as was Yonia Fain. While in Mexico in 1949, Fain painted a 600-square-foot mural in Mexico City’s Pantheon Dolores dedicated to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Diego Rivera subsequently delivered a series of three lectures on the significance of this work in the history of Mexican mural painting. While in Mexico, Fain taught at the University of Mexico from 1947 to 1953.

The United States started to beckon. In 1948, he had a one-person exhibition at the Demotte Gallery in New York. In 1952, Fain represented Mexico in the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. The following year, Fain moved to New York, after seven years in Mexico. Later, Fain told his friends Blanche and Irving Abram that his colors seemed so bright when he came to the United States, much closer to the palette of the Mexican artists than that of Americans.7

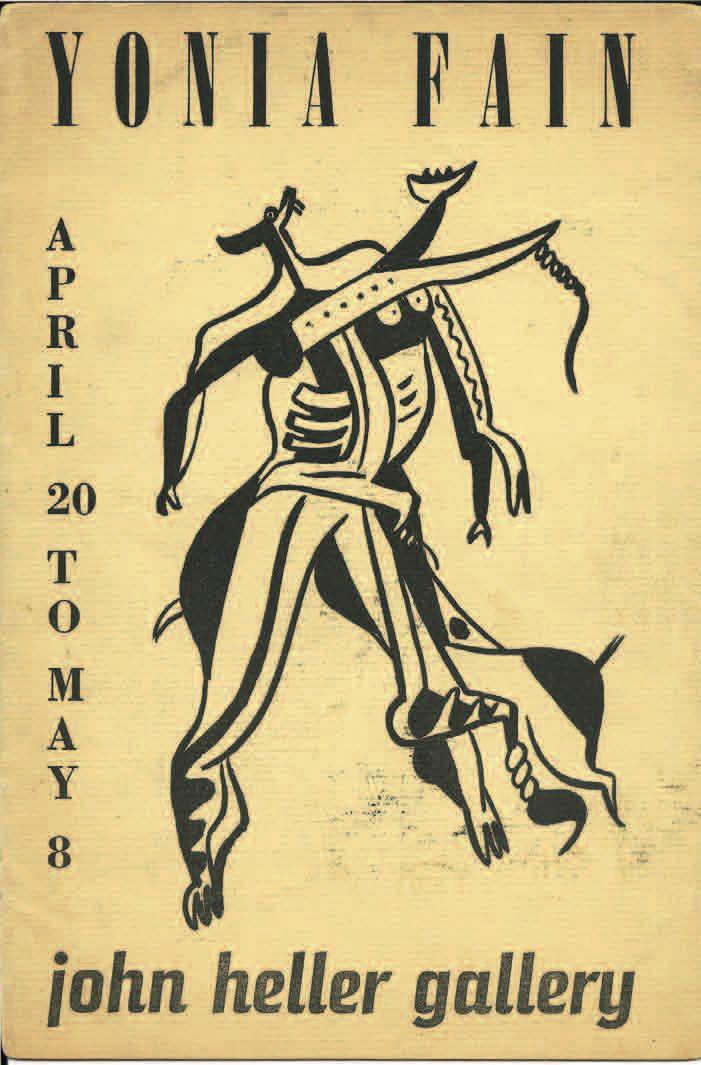

Yonia had a remarkably successful career during his early years in New York. The year after his arrival, he participated in an international group show at the Downtown Gallery called Painters under Forty. Soon, a number of one-person exhibitions followed at notable New York galleries: the John Heller Gallery (1954, 1955), Bodley Gallery (1957), and the Krasner Gallery (1959, 1960, 1961).

This was the Golden Age for art in New York, having become the center of the art world after Paris’ long dominance. For the first time, America was forging its own distinct art movements rather than relying on Europe for its cues. Abstract Expressionism was rising in prominence. Fain was not interested in this movement because he was so tied to humanism and felt the need to portray the brutal suffering caused by the Holocaust, even if indirectly. Yonia’s art and life took place in the vortex of the art world, and while he met and became friends with many of the figures of this time, including Robert Motherwell, even exhibiting with him in the Downtown Gallery group show, Yonia eschewed the concepts of Abstract Expressionism. The emergence of Pop Art, with its ironic take on consumer culture, also did not interest him given his life experiences, nor did the nascent Minimalist movement. Not fitting into any of these categories, Fain began to have less frequent one-person exhibitions in New York galleries. He did, however, exhibit in the important annual shows of Contemporary American Painters at the Whitney (1972, 1973, 1974), the precursor to the Whitney Biennial. He also participated in numerous group shows at the Brooklyn Museum, where he taught in their art school, from 1953

to 1970. Other professional positions included that of professor of art history at New York University from 1965 to 1970, and professor of art and humanities (undergraduate and graduate) at Hofstra University from 1971 to 1985. In 1995, he had a one-person exhibition at the Oxford Institute for Yiddish Studies. In July 1999, a retrospective exhibition of Fain’s work was held at Magdalen College, Oxford University. Other exhibitions followed throughout the years, including a group show at the National Holocaust Museum in 2001, and a one-man show at the Jewish Cultural Centre, London, in 2007.

Featured in Yonia Fain: Remembrance, his large-scale painting Storm, n.d., projects a major sense of drama, tension and movement and can be seen as a metaphor for what humanity has endured in the 20th century. His Untitled painting, n.d., featuring a horse on its back writhing in agony, ties into a long art historical use of animal imagery extending back to Franz Marc and the German Romantic tradition. Irrational and mysterious beings whose thinking process is unknowable, animals represent pure emotion, not reason. In Fain’s The Scream of 1997, his powerful composition relates to Edvard Munch’s famous painting of the same name, and is as emotionally charged as Pablo Picasso’s Guernica

All of Yonia Fain’s paintings exude a sense of history and human tragedy, even if they are not overtly historical. Indeed, he was, and continues to be, interested in painting contemporary history, not mythology or the ancient past. His art works stand as leading examples of a select category or movement known as Holocaust art. He identifies himself as a Holocaust artist, not as a Jewish artist. He also views himself as being transnational and as one of the lucky ones to emerge alive from the Holocaust. He continues to paint every day. Even at the age of 98, there is still a significant project that he would like to do: a major mural work titled A Man in the Twentieth Century. He has made no sketches for it. It is all in his mind’s eye.

An accomplished, creative, and ever-productive artist, Yonia Fain continues to express powerful emotions, not only through his canvases and works on paper, but also in written form. Throughout his life, he has been a distinguished and internationally recognized Yiddish poet.

Dr. Kenneth Wayne Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, Noguchi Museum

Discussion with Blanche and Irving Abram, November 27, 2011

Alone, nd

Oil on masonite

48 x 48 in.

Angel of Victory, c. 1968

Oil on canvas

52 x 43 in.

Courtesy of the Collection of Blanche and Irving Abram

Beloved Visitors, nd Oil on masonite 48 x 52 in.

Cain and Abel, 1965

Oil on canvas

31 x 50 in.

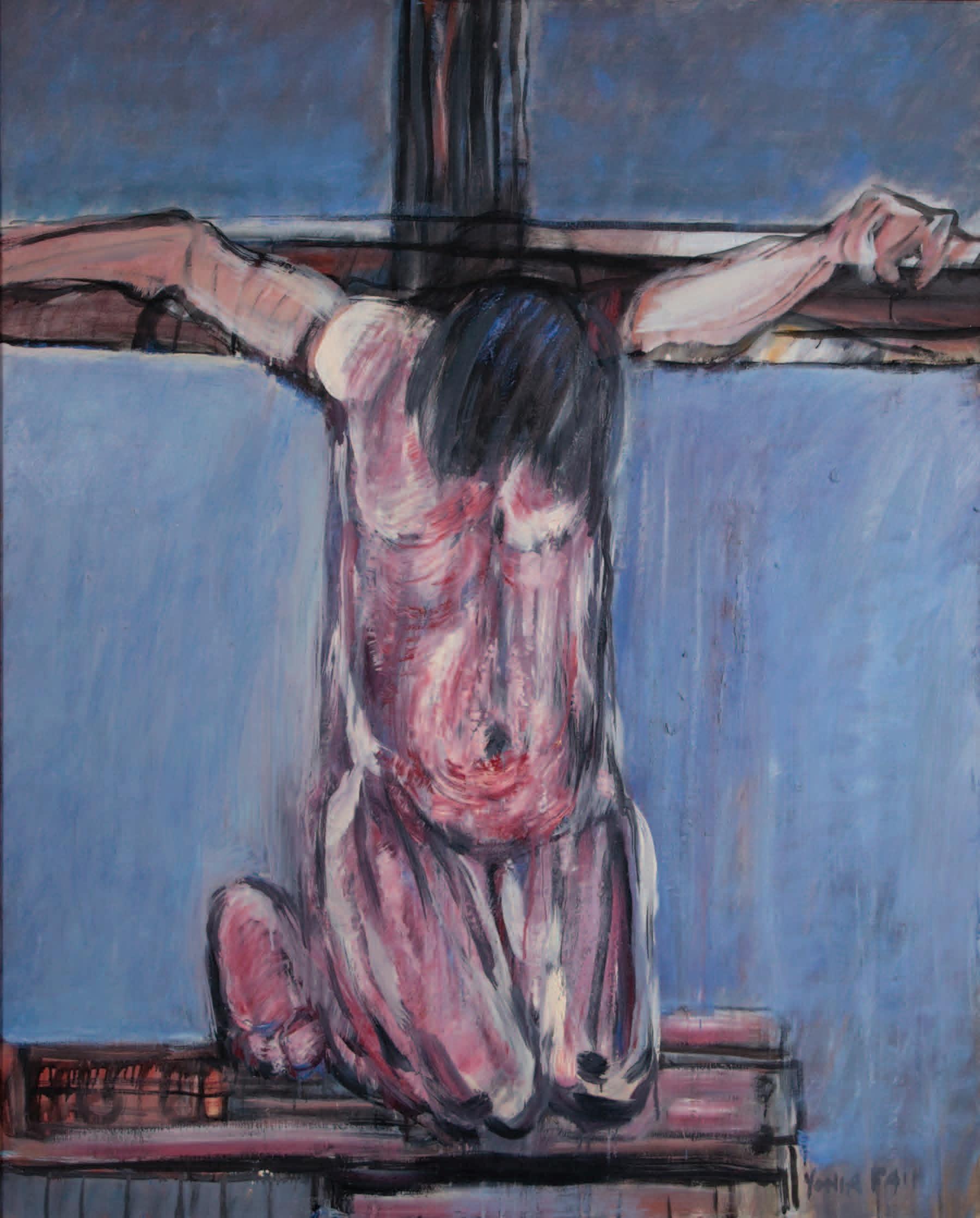

Crucifixion, 1966

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 in.

Gates of Sodom, 1997

Oil on canvas

52 x 47 in.

Holocaust, nd Oil on linen

79.5 x 132.25 in.

, 2012

Mixed media on paper 24 x 36 in.

Memories

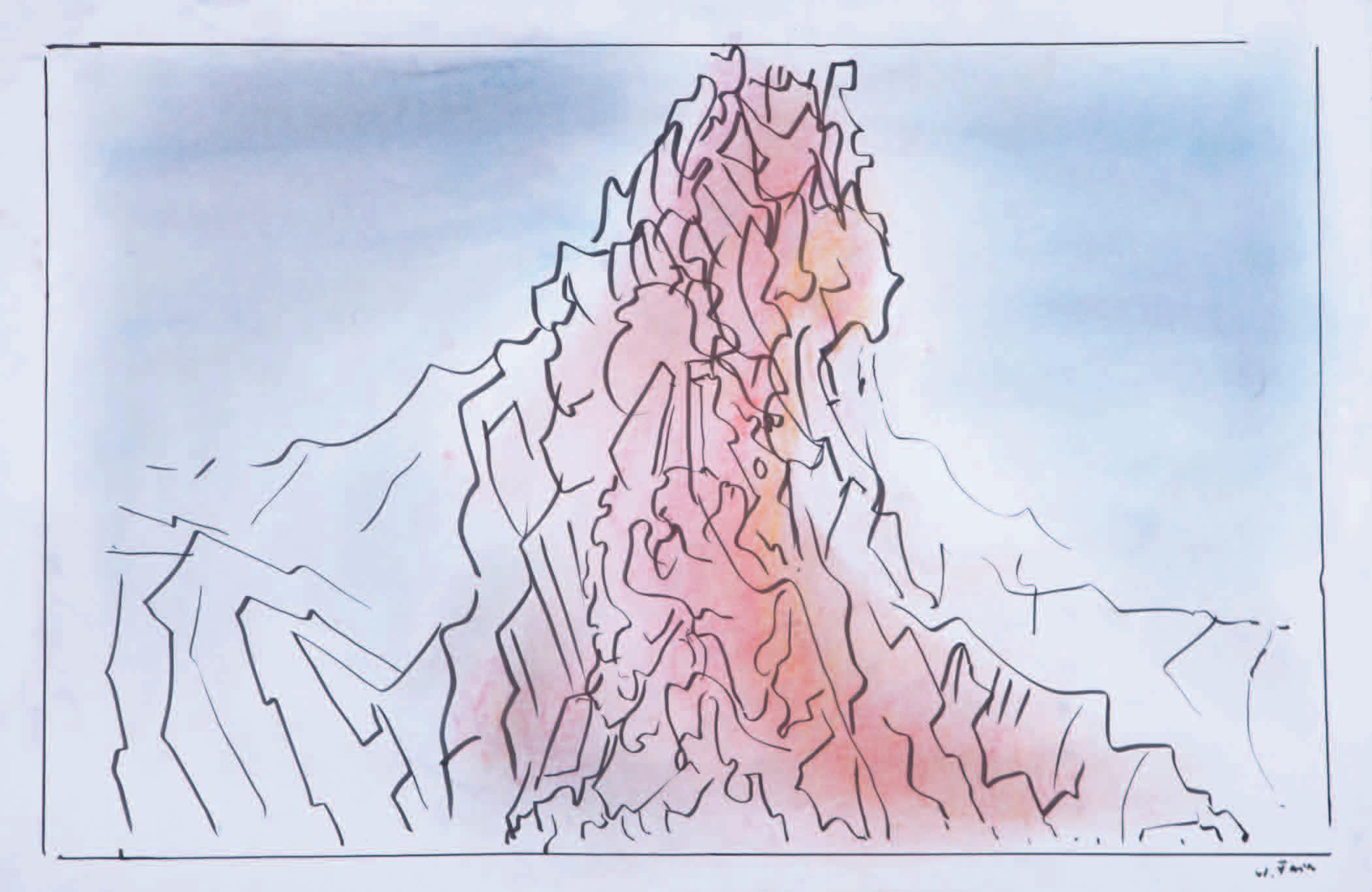

Mountain, 2012 Mixed media on paper 24 x 36 in.

The

The Neighbor, 1995 Oil on

masonite 48 x 44 in.

Prisoners, nd Oil on canvas

26.25 x 50 in.

Roadside, c. 1970

Oil on canvas

40 x 50 in.

Courtesy of the Collection of Blanche and Irving Abram

The Scream, 1962 Oil on canvas 48 x 35 in.

The Scream, 1997 Oil on masonite 53.75 x 48 in.

Squares, nd Oil on masonite 48 x 44 in.

Still Life, 1959

Oil on masonite

36.25 x 48 in.

Storm, nd Oil on canvas

48 x 96 in.

Studio with Two Portraits, nd Oil on canvas

80 x 104 in.

The Throne, nd Oil on masonite

54.25 x 48 in.

Untitled (Slain Bull), c. 1954-1955 Oil on canvas

40 x 52 in.

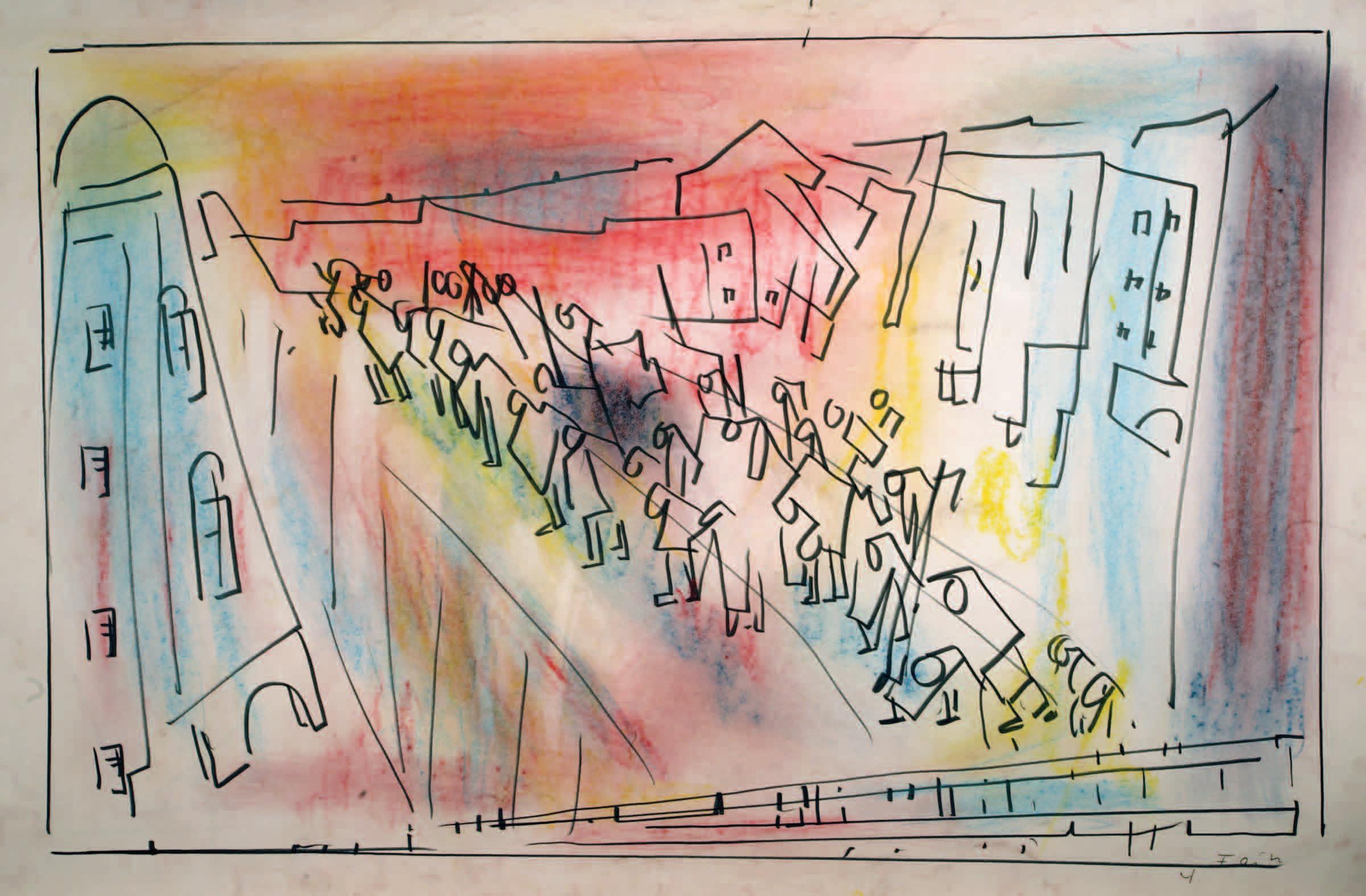

Uprisin g, 2008

Mixed media on paper 24 x 36 in.

The Victim, 2008

Mixed media on paper 24 x 36 in.

22 7/16 x 14 3/8 in.

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886-1957) Roberto Rosales, 1930 Oil on canvas

Courtesy of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY, Gift of Mrs. Bernard Barnes (Carolyn Payne, class of 1934) 1988.50

Rufino Tamayo (Mexican, 1899-1991)

Figure (of a woman), 1939 Oil

15 7/8 x 13 5/8 in.

Courtesy of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph S. Iseman (Marjorie Frankenthaler, class of 1943) 1959.8

on canvas

Yonia Fain: Remembrance Exhibition Checklist

All works of art are created by and courtesy of the artist unless otherwise noted.

Alone, nd

Oil on masonite

48 x 48 in.

Angel of Victory, c. 1968

Oil on canvas

52 x 43 in.

Courtesy of the Collection of Blanche and Irving Abram

Beloved Visitors, nd Oil on masonite

48 x 52 in.

Cain and Abel, 1965

Oil on canvas

31 x 50 in.

Crucifixion , 1966

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 in.

Gates of Sodom, 1997

Oil on canvas

52 x 47 in.

Holocaust, nd Oil on linen

79.5 x 132.25 in.

Memories, 2012

Mixed media on paper

24 x 36 in.

The Mountain, 2012

Mixed media on paper

24 x 36 in.

The Neighbor, 1995 Oil on masonite

48 x 44 in.

Prisoners, nd Oil on canvas

26.25 x 50 in.

Roadside, c. 1970

Oil on canvas

40 x 50 in.

Courtesy of the Collection of Blanche and Irving Abram

The Scream, 1962

Oil on canvas

48 x 35 in.

The Scream, 1997 Oil on masonite

53.75 x 48 in.

Squares, nd Oil on masonite

48 x 44 in.

Still Life, 1959

Oil on masonite

36.25 x 48 in.

Storm , nd Oil on canvas

48 x 96 in.

Studio with Two Portraits, nd Oil on canvas

80 x 104 in.

The Throne, nd Oil on masonite

54.25 x 48 in.

Untitled (Slain Bull), c. 1954-1955

Oil on canvas

40 x 52 in.

Uprising, 2008

Mixed media on paper

24 x 36 in.

The Victim, 2008

Mixed media on paper

24 x 36 in.

Yonia Fain: Remembrance Exhibition Checklist

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886-1957)

Roberto Rosales, 1930

Oil on canvas

22 7/16 x 14 3/8 in.

Courtesy of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY

Gift of Mrs. Bernard Barnes (Carolyn Payne, class of 1934) 1988.50

Rufino Tamayo (Mexican, 1899-1991)

Figure (of a woman), 1939

Oil on canvas

15 7/8 x 13 5/8 in.

Courtesy of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph S. Iseman

(Marjorie Frankenthaler, class of 1943) 1959.8

Der Finfter zman: lider (The Fifth Season: Poems), (Yiddish Edition)

Published by CYCO Bikher Farlag, New York, 2007

Exhibition of Paintings by J. Fein catalogue, 1942

Jewish Club, Shanghai

7 3/4 x 5 1/4 in.

Exposicion de Yonia Fain catalogue with essay by Diego Rivera, 1948

Palacio de las Bellas Artes, Salon Verde, Mexico City, Mexico

8 3/8 x 5 1/2 in.

Quite Simply Poem by Yonia Fain

Included in Yiddish Literature in America 1870-2000. KTAV Publishing House, edited by Emanuel Goldsmith, 2009, pp. 362-363.

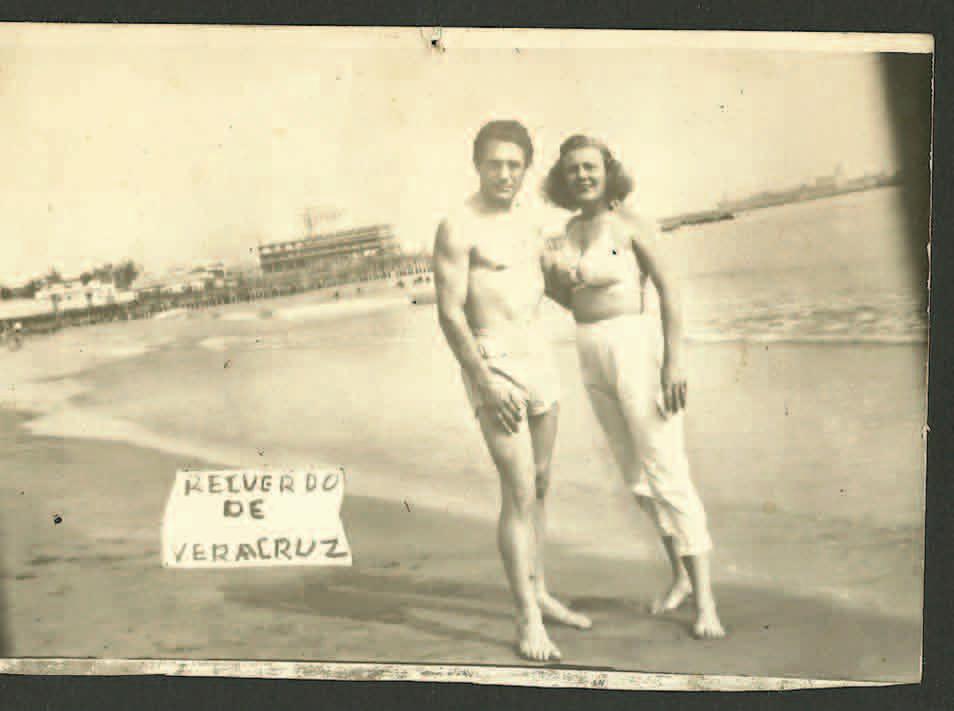

Yonia Fain with Refugees in Shanghai, c. 1941-1945

Photograph

5 7/8 x 4 1/4 in.

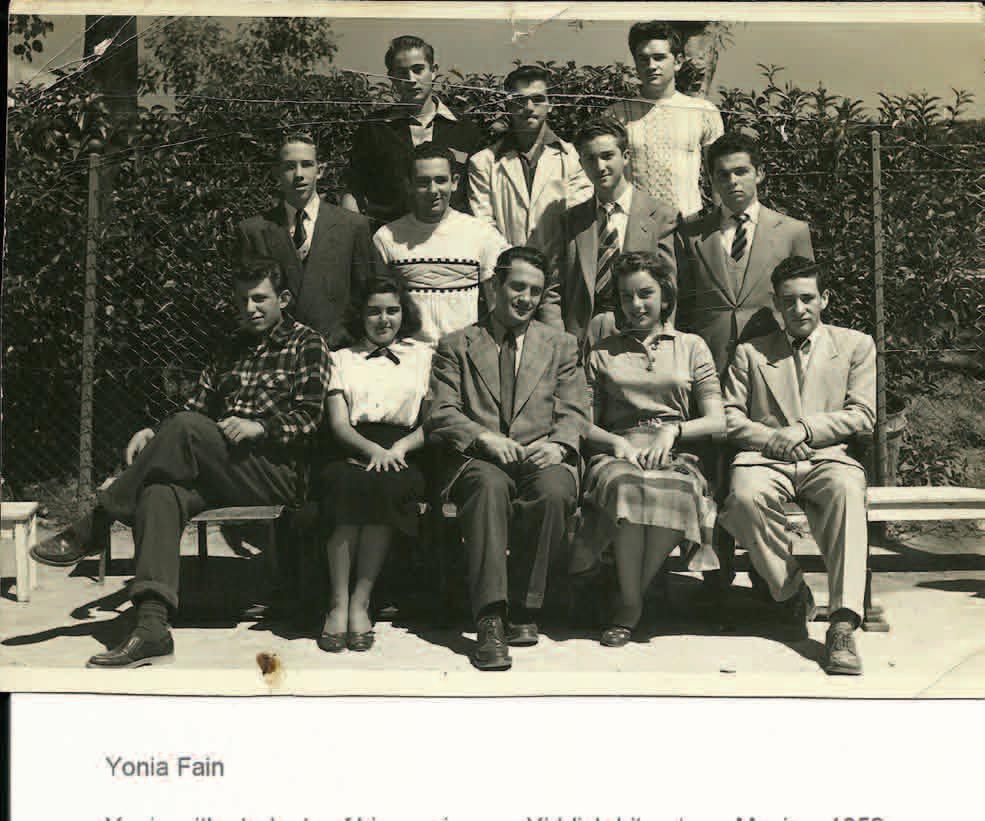

Yonia Fain with Seminar Students, Mexico City, 1952

Photograph

4 5/8 x 6 1/2 in.

Wall Mural and Ceiling Dome Painting for the Memorial Chapel, Panteon Israelita, Cementerio Ashkenazi, Mexico City, Mexico

Photographic enlargements

8 x 10 in.

Timeline

1913 * Born in Kamyanets in Southern Russia near the border of Romania. (*according to the artist)

192 4 Yonia and his family escape the Bolshevik Revolution by moving to Vilnius (Vilna), Poland, where his father is a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Vilnius

193 6 Yonia earns a bachelor’s degree from the University of Vilnius, Poland.

1937 Yonia earns a Master of Fine Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts, University of Vilnius, Poland.

193 9 Yonia flees from Warsaw due to occupation by the Nazis.

194 0 Yonia escapes the Nazis, but is captured by Soviet troops and imprisoned. He and his wife, Nuta, are released into Russia where they obtain Japanese transit visas. They flee the country, traveling through Siberia and on to Japan.

1941 Yonia is forced to relocate to Shanghai, China, in the fall and lives in the International Settlement The bombing of Pearl Harbor traps him in Shanghai He spends the war there and earns a living painting portraits of soldiers; he has a number of exhibitions during this period.

194 2 May 31-June 15: Exhibition of Paintings: Yonia Fain. Jewish Club, Shanghai. Solo exhibit

194 3 A Jewish Ghetto is established in Shanghai in May, and Yonia Fain relocates there along with 18,000 other Jews.

194 6 Yonia moves to Mexico City.

1947 A tliye unter di shtern (A Gallow Under the Stars). Published by Di shtime.

1947-195 3 Teaches at the University of Mexico

194 8 Exposicion de Yonia Fain. Solo exhibition at the Palacio de Las Bellas Artes, Salon Verde, Mexico City, Mexico, in January. Catalog text for exhibition written by Diego Rivera.

194 8 November 29-December 18: Exhibition of Paintings: Yonia Fain. Demotte Gallery, NYC. Solo exhibit.

194 9 Paints 600-square-foot mural in Mexico City’s Pantheon Dolores. Diego Rivera delivers a series of three lectures on the significance of this work in the history of Mexican mural painting

195 0 Galeria Arte Moderno de Caracalla. Solo exhibit.

1952 October 16-December 14: Exhibits in Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting , Department of Fine Arts, Carnegie Institute. Represents Mexico.

195 3 Galerie Arte Mexicana de Inez Amor. Solo exhibit

195 3 Yonia moves to New York City

1954-197 0 Instructor at the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

1956-1957 November 15-January 25: Brooklyn Museum Art School Annual Faculty Christmas Show. The Brooklyn Museum, New York. Group exhibit

1957 October 21-November 2: Yonia Fain. Bodley Gallery, NYC. Solo exhibit

1957-1958 December 9-January 15: Brooklyn Museum Art School Annual Faculty Christmas Show. The Brooklyn Museum, New York. Group exhibit.

1959 March 2-14: Yonia Fain. Krasner Gallery, Madison Avenue, NYC, with catalogue. Solo exhibit

1959 June 28-August 30: 24th Annual Midyear Show. The Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio. Group exhibit.

196 0 Krasner Gallery, NYC. Solo exhibit.

1961 Krasner Gallery, NYC. Solo exhibit.

1964 June: Yonia is featured in a French magazine publication, La Revue Moderne des Arts et de la Vie, for his work as an artist and a teacher

1964-1965 November 28-January 4: Brooklyn Museum Art School Faculty sales-exhibition. The Brooklyn Museum, New York. Group exhibit.

1964-197 0 Teaches at New York University.

1971-198 5 Yonia joins the faculty of the Department of Fine Art and Humanities at Hofstra University, teaching art history and the philosophy of art

1973 Faculty Show. Emily Lowe Gallery, Hofstra University. Group exhibit.

1975 Sean Desmond Gallery, Armonk, New York. Solo exhibit.

1977 Faculty Show. Emily Lowe Gallery, Hofstra University. Group exhibit

1978 Faculty Show. Emily Lowe Gallery, Hofstra University. Group exhibit

198 0 Fain and Gordon: Recent Works. Emily Lowe Gallery, Hofstra University. Two-person exhibit.

198 3 Beloved Strangers. Printed in Israel, Israel-Book Publishing House.

199 5 Nyu-Yorker adresn: Dertseylungen (Yiddish edition). Published by Farlag “Dray shvester.”

199 5 British WIZO and Oxford Institute for Yiddish Studies. Solo exhibit.

1999 July: Retrospective exhibition of Fain’s work at Magdalen College, Oxford University.

2000-2001 Flight and Rescue. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. Group exhibit.

2003 Shards Across Time: An Exhibition in Memorial of Kristallnacht Brooklyn Jewish Arts Gallery, New York. Two-person exhibit.

2007 October 8-November 9: Paintings and Drawings by Yonia Fain. London Jewish Cultural Centre, England.

2007 Der Finfter zman: lider (The Fifth Season: Poems), (Yiddish Edition). Published by CYCO Bikher Farlag.

2008 A Painter’s Witness to History: Recent Work by Yonia Fain. Rochelle and Irwin A. Lowenfeld Conference and Exhibition Hall, Hofstra University

2008 Yonia’s poetry is included in Voices From Shanghai: Jewish exiles in wartime China. Published by University of Chicago Press, edited by Irene Eber.

2009 Yonia’s poetry is included in Yiddish

Literature in America 1870-2000. Published by KTAV Publishing House, edited by Emanuel Goldsmith.

Quite Simply By Yonia Fain

I’ll tell you quite simply: a fire burns, water flows, and only a man who finds himself alone does not live in vain.

High doors decorated with portieres frighten me more than an open grave, and a book with words in love with words is for me a cage, not a house.

Though I’ve achieved very little, and haven’t understood very much either, I’ve lived in terrain too perpendicular for airplanes to fly in.

Yesterday and today meet for me in a cube of sugar between my teeth, and my hand, which shaves me in the light, can understand me in the dark too.

I’m thankful for things without names and for names without things, for tears that come without my knowledge, and for knowledge locked in silence.

I’m thankful to be able to be thankful, for hurrying, though no one has invited me, for gentleness that can bypass harshness, for eagerness to make up in the middle of a fight.

I’ll tell you quite simply: even the darkest hour has its wick, and if my life is no more than a match, I’m thankful for the little flame built into a match.

Yiddish Literature in America 1870-2000. Published by KTAV Publishing House, edited by Emanuel Goldsmith, 2009, pp. 362-363.

Photo credit: Marjorie Pillar, 2012

Hofstra University

Stuart Rabinowitz

President

Andrew M. Boas and Mark L. Claster Distinguished Professor of Law

Herman A. Berliner

Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

Lawrence Herbert Distinguished Professor

Hofstra University Museum

Beth E. Levinthal

Executive Director

Karen T. Albert

Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Caroline S. Bigelow

Senior Assistant to the Executive Director

Kristy L. Caratzola

Collections Manager

Tiffany M. Jordan

Development and Membership Coordinator

Marjorie Pillar

Museum Education Outreach Coordinator

Nancy Richner

Museum Education Director

Graduate Assistants

Karolyn Brosnan

Kaitlin Schneekloth

Nicole Thomas

Undergraduate Assistants

James Anderson

Meredith Maiorino

Melinda Leigh Marr

Vivian Skumpija

Nicholas Stonehouse

Photography of Yonia Fain paintings

Rick Odell