September 4-December 7, 2012 | Emily Lowe Gallery

Curated by Karen

T. Albert

Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Hofstra University Museum

Funding for this exhibition and catalog has been provided by:

Hofstra University

Astoria Federal Savings

Walrath Family Foundation

enocide comes from the Greek word genos, meaning race or kind. Te word genocide was frst coined by Raphael Lemkin during the Nuremberg trials where members of the Nazi regime, the perpetrators of the Holocaust in Germany, were prosecuted for the attempted extermination of the Jews. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, Tird College Edition, 1988, genocide is “systematic and deliberate killing with the intention to destroy a whole national or ethnic group.”

In the preamble to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), adopted on December 9, 1948, by the General Assembly of the United Nations, it states that instances of genocide have occurred throughout history. Such crimes against humanity are condemned by the civilized world. Tragically, there is evidence that genocide has occurred throughout human history in many diferent countries and cultures of our world.

One would hope that as the world becomes more culturally sensitive and the ability to communicate with immediacy on a global scale via social media and improved technologies expands, we will begin to see an end to such senseless hatred and killing.

It is also through the eforts of artists and humanitarians such as Mitch Lewis, who utilizes the acceptable vehicle of sculptural art to convey powerful and painful messages to the public, that we will become even more enlightened about the impact of these atrocities, which have been and continue to be perpetrated against groups and nations of people. It is only through knowledge and awareness that efective change on a global scale will come. It is, in fact, Mitch Lewis’ hope that once viewers understand the magnitude of the impact of the genocide in Darfur, they will be spurred to action. Such action may lead to aid and assistance for the victims, to the public decrying of such crimes, and ultimately to the end to the criminal act of genocide.

We thank Mitch Lewis, the Walrath Family Foundation, Astoria Federal Savings, and Hofstra University for their support of this important exhibition.

BETH E. LEVINTHAL Executive Director Hofstra University Museum

“For evil to fourish, it only requires good men to do nothing.”

A– Simon Wiesenthal

ctivism is defned as vigorous action or involvement as a means of achieving a goal; it is about bringing awareness to an issue and inspiring change. Activism can be expressed in a variety of ways, including writing letters to the editor, lobbying congressional representatives or holding rallies. From Francisco de Goya’s Te Tird of May (1808) to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), and more recently Fernando Botero’s series of paintings of Abu Ghraib (2005), artists have used their individual talents to express their anger and distress about greater humanitarian issues. Many artists believe that visual images, more than words, can evoke a strong, visceral response. In the exhibition, Toward Greater Awareness: Darfur and American Activism, Mitch Lewis expresses his personal outrage about the humanitarian crisis in the Darfur region of Sudan through a most efective form of communication – his sculpture. Lewis’ intention is to raise awareness of this assault on human rights and genocide, with the hope that his sculpture will serve as a vehicle for social change. He believes that the visual arts can impact people on a profound emotional level.

Lewis, born in 1938, earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Pratt Institute, studied at the Art Students League, and completed graduate work in sculpture at Eastern Carolina University. In his sculpture Lewis has focused on the human form. His earlier work was traditionally fgurative and exemplifed classical ideals of beauty. He has also been interested in archaeology and the idea of the piecing together of fragments to create a whole.

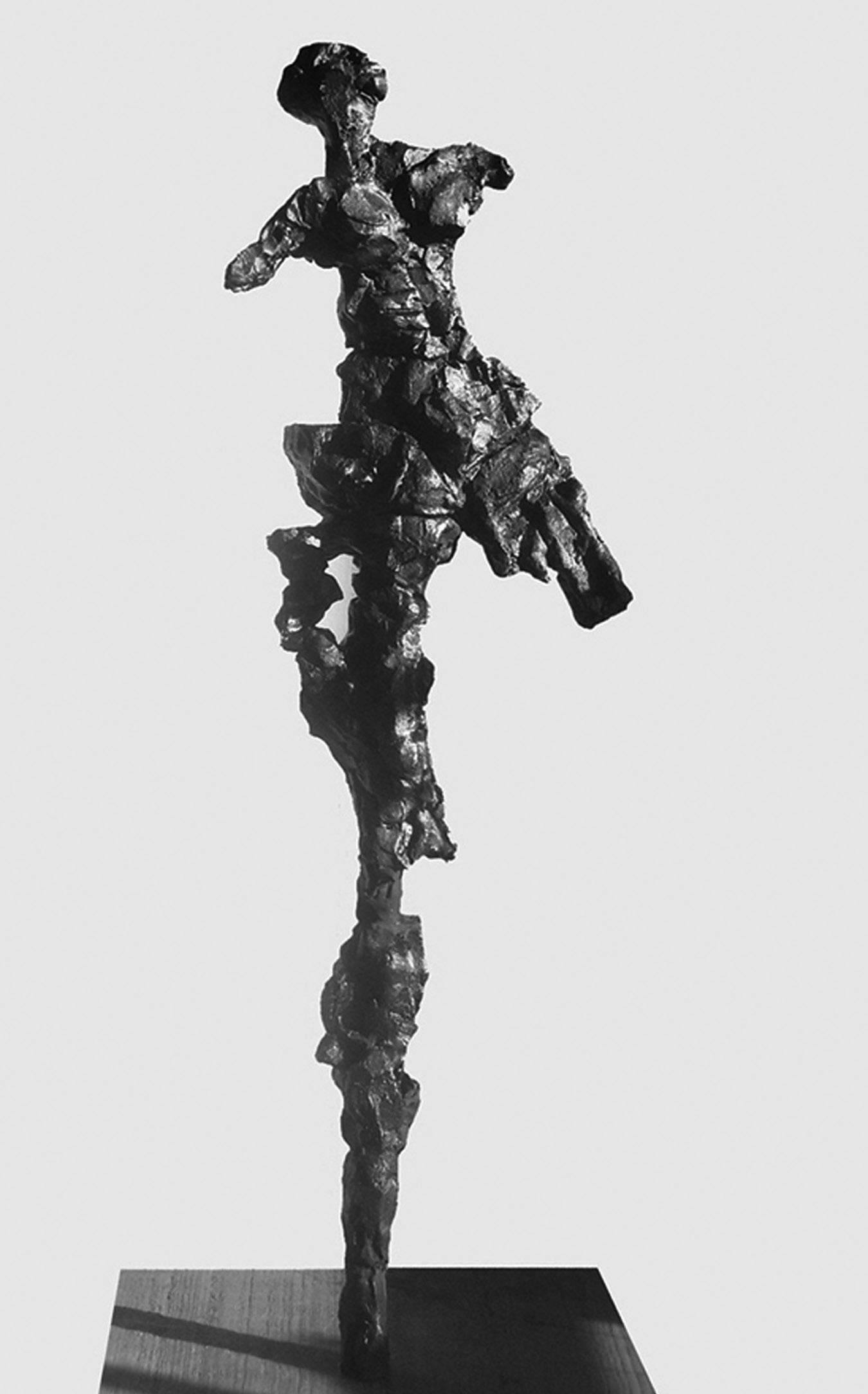

His sculpture in this exhibition refects a bleaker side of humanity, specifcally the atrocities in the Darfur region of Sudan. Using a variety of materials, such as terra cotta, bronze, resins, and wire, Lewis creates works that reveal the physical and psychological scars lef behind by violence and brutality. His fgures, such as Darfur Legacy #2 and Darfur Legacy #3 (both completed in 2009), seem fragile but also show an inner strength and dignity. Te fragmented female forms refect the brutal violence against women and show their vulnerability. Tere is a gracefulness to the fgures that is shown through the use of elongated lines. With their missing limbs, they are also reminiscent of Greek and Roman sculpture from antiquity.

Te installation Homage to Kevin Carter (2010) refers to a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken by Kevin Carter (1960-1994). Carter, a South African photojournalist, captured an image of a starving

Sudanese child with a vulture lurking in the background. Lewis interprets the image in three dimensions, showing the vulture looming over the emaciated fgure. Hunger, malnutrition and starvation remain major problems for the refugees of Darfur and other African peoples.

Tousands of those who have fed their villages are children. One of the outcomes of the hostilities is the abduction of children and their sale to warring militias as child soldiers. Child Soldier (2010) depicts the armed “soldier” aggressively standing over the kneeling woman. In another time and place the woman would be nurturing and protecting the child. Lewis uses role reversal to emphasize and highlight the issue of child soldiers, which occurs not only in Darfur but other regions of Africa.

In Hiding from Janjaweed (2010) Lewis illustrates a common practice when villages are attacked – the women and children hide in the woods while the men try to fend of the attackers. Te Janjaweed, meaning “a man with a gun on a horse,” are members of nomadic tribes who have long been at odds with the farmers and villagers. Te use of rape as a weapon of war is addressed in Janjaweed Rape (2011). Using rape is a brutal and dehumanizing strategy where the victim is stigmatized and ofen shunned by other villagers. Te hostility and aggression of the group of men is shown through their body language and expressions as well as their placement above our sightline.

Lewis is currently participating as a regional organizer for One Million Bones, a collaborative art installation designed to recognize the millions of victims who have been killed or displaced by ongoing genocide and humanitarian crises in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia and Burma. Te collected artwork bones will be displayed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in spring 2013.

In 2010 Save Darfur Coalition presented Mr. Lewis with its frst Darfur Hero award; he has since received grants and other accolades for his work on this issue. His works are exhibited in museums, art galleries and private collections both nationally and internationally. Two recent exhibitions were held at Bank of the Arts Gallery, New Bern, NC (2010), and at FedEx Global Education Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC (2011).

Mitch Lewis continues to use his sculpture to address humanitarian and socio-political issues with the intention of increasing public awareness and the hope of bringing about positive social change.

KAREN T. ALBERT Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections

For me, art has always been a compelling agent for creating public awareness of social issues, and ultimately bringing about change. Tis philosophy infuenced my work when I frst became aware of the unspeakable brutality that was happening to innocent women and children in Darfur. Te post-Holocaust outcry of “never again,” to me, included not only the Jewish people, but all of humanity. But once again, in my lifetime, I was witnessing genocide; this time not only in Darfur, but throughout the African continent. Te plight of these ill-fated people became the driver that has dictated my artistic direction. I express my personal outrage using my most efective form of communication – sculpture. My current focus is on creating art that raises public awareness of this assault on human rights and hopefully becoming a vehicle for infuencing social change.

Te Toward Greater Awareness: Darfur and American Activism exhibition has given me the opportunity to be proactive. Trough this exhibition, I am able to initiate a dialogue with the viewer about the physical and psychological scars lef on mankind by a culture of violence and brutality. I have made the sculptures purposely provocative and invite contemplative exploration of this troubling issue. Te pieces depict African women as fragmented fgures, and this fracturing is a commentary on the vulnerability of the human condition. While I expose the fragility and vulnerability of these women, I also portray their strength and dignity. Te sculptures in this exhibition portray some of the most troubling issues of this confict: rape used as a weapon of war, the kidnapping and exploitive use of child soldiers, disfguration and malnutrition.

Because university students are among the most politically active voices about Darfur, I am presenting this exhibition at university art museums and human rights centers around the country. My role as an artist is to raise awareness, through my work, of the genocide that is devastating Darfur. However, I’ve come to realize that the exhibition also serves as a role model for a new generation of artist/activists. I hope to give them an understanding of the enormous power of art and their potential as artists to become a voice for human rights.

I believe that genocide afects us all. Te passive observation of the mass murder of men, women and children makes us all accomplices. When I was a youngster, the Nazi death camps were liberated, and we were confronted with the horrors of genocide. Te world acted shocked and said, “we never knew.” My goal is to use my art to confront viewers with the stark reality of Darfur and to say to all who view the exhibit, “now you know ... and now you must act.”

108 x 24 x 18 in.

The Gatherers, 2011

Homage to Kevin Carter, 2010

All sculptures are by Mitch Lewis and are on loan from the artist.

Child Soldier, 2010

Terra cotta

18 x 13 x 14 in.

Darfur Legacy #2, 2009

Hi-fred stoneware

120 x 25 x 15 in.

Darfur Legacy #3, 2009

Hi-fred stoneware

108 x 24 x 18 in.

Darfur Legacy Maquette #4, 2009

Terra cotta

27 x 8 x 3 in.

Darfur Legacy Maquette #6, 2009

Terra cotta

27 x 11 x 6 in.

Darfur Legacy Maquette #7, 2009

Terra cotta 24 x 8 x 7 in.

Janjaweed Rape, 2011

Terra cotta 142 x 198 x 30 in.

Te Gatherers, 2011

Terra cotta, wood and fabric 19 x 16 x 23 in. each

Hiding from Janjaweed, 2010

Hi-fred stoneware and bamboo

132 x 130 x 96 in.

Homage to Kevin Carter, 2010

Hi-fred stoneware, wood, leather, burlap and cheesecloth

96 x 60 x 72 in.

Stuart Rabinowitz President

Andrew M. Boas and Mark L. Claster Distinguished Professor of Law

Herman A. Berliner

Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Afairs

Lawrence Herbert Distinguished Professor

Beth E. Levinthal Executive Director

Karen T. Albert Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Caroline S. Bigelow Senior Assistant to the Executive Director

Kristy L. Caratzola Collections Manager

Tifany M. Jordan Development and Membership Coordinator

Marjorie Pillar Museum Education Outreach Coordinator

Nancy Richner Museum Education Director

Graduate Assistant

Kaitlin Schneekloth

Undergraduate Assistants

Elizabeth Goodrich

Jody Kass

Meredith Maiorino

Melinda Leigh Marr

Nicholas Stonehouse