42 minute read

Rethinking Hoogebergh Early Rensselaerswijck’s Most Elusive Farm

Rethinking Hoogebergh: Early Rensselaerswijck’s

Most Elusive Farm by Rudy VanVeghten

Advertisement

Hudson River Landmark—Perched at the foot of a low promontory about five miles below Albany, the Staats house on the Hudson River has been known for over three centuries as Hoogebergh. That name, however, originated with one of Rensselaerswijck’s earliest farms several miles to the north.

THERE IS A historic home about five miles south of Albany gracing the east shore of the Hudson River. Located at the lower end of Papscanee Island at the foot of a forty- to fifty-foot knoll, the farm and homestead have been known for over three centuries by the intriguing Dutch name Hoogebergh.

Owned for many generations by the Staats family, the farm and its owners are the topic of a relatively recent book by the late William L. Staats titled Three Centuries on the Hudson River: One Family . . . One House–The story of Hoogebergh (1696–2009) and the eleven generations of the Staats family who have lived there.

But Hoogebergh (Dutch for “high hill”)

Rudy VanVeghten, a former community newspaper editor, is a frequent contributor to de Halve Maen as well as serving as the journal’s copy editor. This essay is a supplement to a series arising from Mr. VanVeghten’s research on Gerrit Teunisse van Vechten and his family that appeared in the Winter and Spring 2018 issues of de Halve Maen. existed both as a farm and as a geologic feature several decades before it found a permanent residence along New York’s principal river in the late seventeenth century. Tracking Hoogebergh’s history and original location provides an exercise in the importance of studying resources critically, that is by scrutinizing primary source materials and analyzing how errors often occur in the composition, duplication, transcription, publication, and understanding processes.

Hoogebergh in the Sources. There are a number of references to Hoogebergh in the record books. Listed below are a selection that are especially useful in determining the original geographic location of the farm:

Reference 1: In the winter of 1651, Rensselaerswijck Director Brant van Slichtenhorst, also serving as sheriff and head prosecutor, charged Jacob Lambertse with assaulting and failing to show proper respect to the director. During the previous October when he and other farm hands observed Slichtenhorst’s party approaching below, Lambertse strapped a sword to his side and marched down the hill to intercept Slichtenhorst. “Jacob Lambertsz, being armed with a sword on his side, dared by word and deed, on the Hoogen Berch, in the highest manner to insult the director,” reads the court account of the incident. 1

Reference 2: By the summer of 1651, Rensselaerswijck Director Brant van Slichtenhorst was detained by New Netherland Director-General Pieter Stuyvesant, and a Captain Slijter was temporarily in charge of the patroonship. He compiled a list of working farms in the colony, including one leased to Gysbert Cornelisse van Breuckelin located “aende Hooge barch Van Cristal (on the high hill of crystal).” 2 An explanation of this “crystal” is included later in this essay.

Reference 3: On June 23, 1654, Jan Baptist van Rensselaer, who replaced Slichten

1 A. J. F. Van Laer, trans. and ed., Minutes of the Court of Rensselaerswijck 1648–1652 (Albany, 1922), 142 [hereafter MCR]. 2 A. J. F. Van Laer, trans. and ed., Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts (Albany, 1909), 741 [hereafter VRBM].

Source of Crystal—Known variously as Mill Creek, Red Mill Creek, or in the 1630s as de Laet’s Kill, the stream that drains into the Hudson opposite old Albany was the source of crystals discovered by early residents of Rensselaerswijck. Patroon Kiliaen van Rensselaer encouraged his administrators to locate “the mountain from which the same drops into the creek.”

horst as colony director, renewed Gysbert Cornelisse’s lease “of the farm called de Hoogeberch.” In a footnote describing the farm’s location, editor A. J. F. Van Laer explained that the farm “was situated on the east side of the river, near the present Mill Creek.” This muellenkill was earlier called de Laets Kill by Jan Baptist’s father, Kiliaen. Today it empties into the Hudson just below the Dunn Memorial Bridge (Routes 9/20). 3

Reference 4: In 1660, Jeremias van Rensselaer, who replaced his brother Jan Baptist as director, reported that Sander Leendertse “has also cleared a good part of the Bergh, opposite the fort.” Contrary to his earlier assessment, translator Van Laer added a footnote identifying Hoogebergh with the farm at the bottom end of Papscanee Island rather than along the Mill Creek. 4 Researcher Shirley Dunn voiced doubt about Van Laer’s note: “This identification seems rather doubtful,” Dunn said in an earlier de Halve Maen essay on Hoogebergh, “because the small hill on Papscanee is not immediately opposite the fort.” 5 Fort Orange was located near the west end of today’s Route 9/20 bridge.

Reference 5: In the spring of 1666, a disastrous flood damaged many farms along the upper Hudson River. Two years later Jeremias van Rensselaer described the partial success of recovering from the catastrophe. “Jan Tyssen’s farm is still in fair condition, as is also that on the Hooge Bergh (although the land was largely spoiled by the ice drift, as in some places the sand deposited on it is knee deep).” Editor Van Laer in his 1932 publication of Jeremias’ letters adds a footnote that Hoogebergh is located “On Papscanee Island,” again contradicting his earlier Mill Creek description.” 6

Reference 6: On September 28, 1678, Gerrit Teunisse, who had received a patent from Gov. Edmund Andros for land lying inland from Papscanee Island, leased some of that land to Jan Roose. In the lease, the property is described as “twenty-two morgens of woodland lying behind the farm of the Hooghen Bergh where Gysbert Cornelisz now dwells.” Here again, Van Laer in 1918 (before his thinking had changed) added a footnote about Hoogebergh that “This farm was situated on the east side of the Hudson river, near the Mill creek in the present town of East Greenbush.” 7

Reference 7: Residents of Albany about November 1679 witnessed a major fire that destroyed the Hoogebergh farmhouse and barn. A description of the spectacular blaze comes from a letter by Maria van Rensselaer: Friday, toward noon, cries were heard that the farm of the Hooge Berg was on fire, so that many people at once ran toward it and found it to be true. Before any one could get there, everything was burned, the house, barn, two barracks full of grain, yes even the pig sty. The man himself [farmer Gysbert Cornelisse] was so badly burned that Mr. Cornelis [van Dyck, a doctor] doubts whether he will live, and this because he was so busy with the animals. The woman’s face is burned because she tried to get her blind mother out of the burning house, which she just managed to do. Eleven cows were burned, but the milch cows and the horses they got loose. Everything else was burned, the linen, woolens, bed and household effects, yes, even the pots and kettles were melted. 8

In a footnote to this letter, editor Van Laer in 1935 reported that Hoogebergh is “A farm on Papscanee Island, afterwards known as Staats Island, which since 1648 had been leased to Gysbert Cornelissen van Breuckelen, often referred to as Gysbert Cornelissen van den Berg.” 9 Note again how this description disagrees with Van Laer’s earlier understanding from the third and sixth references above. Gysbert Cornelisse did survive and following his recovery was involved in a fencing dispute with neighboring farmers, indicating the location of his farm had by 1681 moved to the lower end of Papscanee Island. 10

Reference 8: Kiliaen van Rensselaer, son of Jeremias, confirmed Gerrit Teunisse’s ownership of the land known as Schonevelt that Gov. Edmund Andros had patented to

3 Ibid., 769, 769n.

4 A. J. F. Van Laer, ed. and trans., Correspondence of Jeremias van Rensselaer (Albany, 1932), 228, 228n [hereafter CJVR]. 5 Shirley Dunn, “Settlement Patterns in Rensselaerswijck: Tracing the Hoogebergh, a Seventeenth-Century farm on the East Side of the Hudson,” in de Halve Maen (Spring 1995), 16–17.

6 CJVR, 406–407, 406n.

7 Jonathan Pearson, Early Records of the City and County of Albany and Colony of Rensselaerswyck, revised and edited by A. J. F. Van Laer, 4 vols. (Albany, 1918), 3:458, 458n [hereafter ERA]. 8 A. J. F. Van Laer, trans. and ed., Correspondence of Maria van Rensselaer (Albany, 1935), 27 [hereafter CMVR]. 9 Ibid., 27n. Curiously, Van Laer cites Munsell, Annals of Albany vol. 7, 101–102, which deals not with the sale of the lower end of Papscanee Island, but with the farm of Cornelis Teunisse Van Vechten at the top end of the island. 10 A. J. F. Van Laer, Minutes of the Court of Albany, Rensselaerswyck and Schenectady, 3 vols. (Albany, 1928), 3:108–109 [hereafter MCARS].

him in 1677. A deed recorded on August 6, 1696, described the land as situated “near the South end of the Island called Paeps Knee, beginning from the Road or highway between the farm belonging to Saml Staats and Barent Reynders att the South end, and the aforesaid Schonevelt, and so Easterly to the foot of the Hill just behind said land which lies to the Eastward of the farm called the Hoogebergh as also that small Island lying in Paeps Knees Creek on the west side of the aforesaid farm, known by the name of Hendrick Frederickes Island with a certain Island called Mooermans Island with their appurtenances lying and being in the Manor and Colony aforesaid near the East side of Hudsons River and to the Northward of Berren Island as the farms are now in the possession of him the said Gerrit Tunissen according to his Patent.” 11

Parsing the Story. Historians frequently confront new discoveries that contradict previously understood interpretations. Such was apparently the case for early twentiethcentury New York Archivist Arnold Van Laer in attempting to determine the location of the Rensselaerswijck farm known as Hoogebergh. As noted in the third and sixth references above, Van Laer in his earlier years determined this “high hill” farm was located in the vicinity of the stream now called Red Mill Creek that flows through the town of East Greenbush and the city of Rensselaer and into the Hudson. In two of his publications in the 1930s, however, he presented a contradictory determination that Hoogebergh was located on the south end of Papscanee Island. Was one location correct and the other not? And if so, what caused him to change his mind?

It appears Van Laer’s reasoning for his earlier Mill Creek opinion has to do with the crystal noted in reference 2. Gysbert Cornelisse van Breuckelin, according to the 1651 inventory of colony assets, leased a farm “on the high hill of crystal.” Patroonship founder and Amsterdam jeweler Kiliaen van Rensselaer had been dead for eight years by the time this inventory was compiled. His excitement over the discovery of crystals, however, had clearly passed down to those who followed in ownership and management of the colony.

Reference to Hoogebergh —This confirmation deed between Kiliaen van Rensselaer (son of Jeremias and grandson of the first patroon) and Gerrit Teunisse mentions Hoogebergh, but leaves it in doubt whether the name refers to the Staats’ new farm on Papscanee Island or the steep hill on the mainland to the east.

Crystals were originally found in the early 1630s along the mill stream dubbed de Laets Kill by the patroon. In a letter to fellow investor Johannes de Laet, Van Rensselaer wrote, “As to the east side [of the Hudson], we have the lands situated opposite Fort Orange and Castle Island, from paep Sickenees kil northward past the falls of de laets kil thus named by me, which creek runs far inland and in which rock crystal is found, according to Director [Peter] Minuit, to which we must pay more attention in the future.” 12

In the summer of 1632, Van Rensselaer enlisted Rutger Hendricksz van Soest as colony schout or sheriff. In a list of instructions to the officer, the patroon specified, “The officer is hereby warned that rock crystal is found in de Laets kil opposite Fort Orange, above and inland from the dwelling of Roeloff Jansz, and that care should be taken to see whether the mountain from which the same drops into the creek can not be found.” 13

Van Soest didn’t work out, and in 1634 the patroon sent over Jacob Planck as his new sheriff. In an October 1636 letter, Van Rensselaer wrote to him instructions regarding the gemstones. “I have received your samples; the crystal is the best,” he wrote. “Now that so many people come there, take at once a trip into the country to find out whether there are any minerals, especially, as I hear, that there is a rock of crystal above de laets Kiel where the mill stands. Inquire about this some time and write me whether there is a great quantity of it and send me of the purest, instead of a piece as large as a hazelnut, a couple of barrels as a sample. It is said to extend as far as two or three leagues upwards.” 14 By this time, Van Rensselaer likely knew from the previous samples that this crystal was nothing but common quartz, but his hope for something more valuable persisted.

Van Rensselaer was always searching for new farmers to populate his remote patroonship. In 1637 he sent over Cornelis Maasen van Buren, a former farm hand on the de Laetsburg farm, and Simon Walichs, both of whom took assigned farms at the north end of Papscanee Island. A year later,

11 Albany Institute of History and Art, McKinney Library, Deeds and Indentures Collection, William Patterson Van Rensselaer Papers, BM 400/5/12; Shirely Dunn, “Settlement Patterns in Rensselaerswijck: Locating SeventeenthCentury Farms on the East Side of the Hudson,” in de Halve Maen (Fall 1994), 72.

12 VRBN, 198.

13 Ibid., 210.

he had Planck establish three additional farms. Best of these was a farm stretching just south of the nascent Greenbush village and the greynen bosch (pine woods), from which it derived its name, down to the upper portion of Papscanee Kill. This farm the patroon assigned to his cousin Mauritz Jansen van Brockhuysen. Planck was then to establish a second farm “south of the farm of mauris Jansen, where there is room enough.” Assigned to former West India Company apprentice farmer Teunis Dirckse van Vechten, this farm was wedged between Papscanee Kill and the ridge of hills to the east. 15

“Because You Came Last.” A third farm established in 1638 was even less desirable. Instead of being situated on the silt-washed Hudson River lowlands, it was perched on top of the forested ridge back from the river. Michiel Jansen van Scrabberkercke was the farmer assigned to this backland parcel. Not only did he have poorer soil on which to establish crops, he would have faced the added task of clearing trees and rocks from the land before he could even plow. A literate young man, Michiel Jansen respectfully expressed displeasure over his assigned farm. In a June 1640 letter, the patroon answered him, “Because you came last I have given you this farm, but do right, be honest and do not let them [other farmers] stir you up; I shall remember you in such way that you will get along well.” 16

It should be noted that when these farmers came to America from the Rhine delta region of the Dutch lowlands, such natural wonders as clean water, game-filled forests, and mountains were largely unfamiliar to them. Although a ridge rising only two to three hundred feet above river level might seem rather diminutive to us, to the Netherlands immigrants they were all high. It is likely the term hooge bergh was used to define the entire ridge back from the east bank of the Hudson, starting across from Fort Orange and extending several miles south-southeast, well before it became associated with a farm situated on that ridge. This explains why Michiel Jansen’s farm was subsequently referred to as “on the high hill” (aende Hoogebergh) and its farmers as “of the hill” (van den Bergh).

One way the patroon suggested rewarding Michiel Jansen focused on the potential value of the area’s crystal. It seems the hilltop farmer had located the elusive source of the gems on his farm. In May 1640, the patroon wrote to his nephew Arent van Curler, “Send me without fail some barrels of the crystal found in the hill of michiel jansz. Have the expense of digging it noted down, I can see then whether there is any money in it or not, for it is of little importance; yet if it is large, white and clear, it is worth something. But send me good and bad as it comes and let no one pick out the best pieces and hold them back. It would be best in Michiel did it himself and got some profit from it too; I think he is one of the most upright farmers in the colony, and when there is an opportunity I shall have an eye to his advantage. He writes most politely of all; let him do what is right and he will be treated well by me.” 17

Michael Jansen, however, didn’t follow Van Rensselaer’s suggestion. In a June 16, 1643, letter, Van Curler responded to his uncle, “Regarding the crystal near Machiel [Jansen’s house, of which your Honor] writes me that I should send over some more samples, I have urged M[achiel Jansen] and others sufficiently to dig it up, but they do not care to do it, apparently because they dread the labor, and it will [not] come out [by it]self.” 18

Van Rensselaer died late in 1643, and Michiel Jansen left Rensselaerswijck colony in 1646, later becoming a leading citizen of New Amsterdam. Although the mineral finds on the high hill farm never amounted to anything, the dream of Inca-like fortunes persisted for several years as the location retained the moniker Hoogebergh van crystal at least through 1651. 19 Eventually the

15 When Mauritz Jansen proved to be a disappointment, his farm was offered up for auction in 1640 (Ibid., 493). Bidding was won by Teunis Dirckse, who thereby greatly increased the size of his own farm (Ibid., 563). 16 Ibid., 499. Michiel Jansen and his descendants later adopted the surname Vreeland.

17 Ibid., 489.

18 A. J. F. van Laer, “Arent van Curler and His Historic Letter to the Patroon,” in The Dutch Settlers Society of Albany Yearbook 1927–1928 vol. III (Albany, 1927), 22. Here, Van Laer uses brackets to indicate gaps in the firedamaged original letter that he filled in from a previous translation by Edmund O’Callaghan.

18 VRBM, 741.

19 Dunn, “Hoogebergh,” 15.

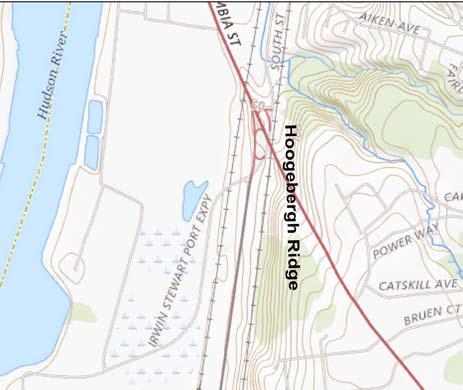

The Original “High Hill”?—Earliest references to Hoogebergh, as well as some later mentions, pertain to a hill rather than to the farm located on the hill. As multiple references designate the hill was opposite Fort Orange, the most likely possibility was the ridge that begins at the northern edge of present-day East Greenbush and extends several miles south parallel to the Hudson River. Note the stream running along the northeasterly side of the ridge.

crystal dropped out of the description, and locals shortened the name to simply Bergh or Hoogebergh.

Van Laer had good reason to conclude early on that the Hoogebergh farm was located on the Mill Creek or de Laet’s Kill, since that is where the crystal stones were first discovered. But why did the famed archivist change his thinking in the 1930s to believe the farm was instead located at the lower end of Papscanee Island? Most likely, this is because the Staats family who have resided there for numerous generations have called it Hoogebergh since at least the turn of the eighteenth century.

There are a couple other clues, in addition to the link between the crystal and Mill Creek, that prove the farm did not originally exist on Papscanee Island. Researcher Shirley Dunn, in her Hoogebergh essay, determined as much. “The precise location of the farm of Michiel Janse van Schrabberkercke and his early successors is not known,” she notes. Although she agrees Hoogebergh did not start out on Papscanee Island, she rejects Mill Creek as a possible location. “The site of the farm in the early years was on a mainland hill, not far from the Hudson River, in present-day Schodack,” she writes. 20

By taking a closer look at some of the references itemized above, it looks like Van Laer’s early understanding of a more northerly location is actually closer to the mark than either Schodack or lower Papscanee.

Gysbert Cornelisse Takes Over. After Michiel Jansen left Hoogebergh in 1646, interim colony director Anthony de Hooges assigned Teunis Cornelisse van Vechten in charge by means of two successive one-year leases. Teunis Cornelisse (not to be confused with his older first cousin and neighboring farmer Teunis Dirckse) was head farmer on the hill when Brant van Slichtenhorst arrived in 1648 to take over as patroonship director. Early in his tenure, Van Slichtenhorst replaced Teunis Cornelisse with new arrival Gysbert Cornelisse, who emigrated from the Vecht River village of Breuckelen north of Utrecht, Netherlands. 21

One of the earliest documented references to Hoogebergh comes from an October 1650 incident involving then colony director Brant van Slichtenhorst and farm worker Jacob Lambertse (reference 1 above). Working in the cleared fields on the hill, Lambertse and others were able to see the director and his party crossing over from the growing village that later became Beverwijck (Albany) and approaching the farm, whereupon Lambertse descended the hill to annoy Van Slichtenhorst. A likely location for this to have occurred was the hill directly back from the ferry landing in Greenbush. According to court records, neighboring farmer Teunis Dirckse was present during the incident, apparently assisting Gysbert Cornelisse in spreading manure on his fields. 22

Teunis Dirckse had formed a neighborly friendship with former Hoogebergh farmer Michiel Janse and carried that relationship forward to new owner Gysbert Cornelisse. In addition to helping with farm chores as noted above, Teunis Dirckse backed his neighbor as surety for the renewal of his lease in 1654. 23 “Gysbert Cornelise,” as Shirley Dunn notes, “seemed to be quite closely associated with Teunis Dirckse.” 24 This close association with both Hoogebergh farmers Michiel Jansen and Gysbert Cornelise suggests the closeness of the hill farm to Teunis Dirckse’s farm, located along the south edge of the grenen bosch (pine woods) that gave the Greenbush village its name. 25

Through the next couple of decades, Gysbert Cornelisse seems to have dedicated himself pretty much to his farm work, appearing in court records far fewer times than his brother Claes Cornelisse, who worked as a laborer on the farm. One notable transaction involving the Hoogebergh farmer came in 1662, when he purchased the farm buildings and structures of a Marten Cornelisse. “On this day, the 20th of May 1662,” reads the deed, “Marten Cornelisz acknowledges that he has sold and Gysbert Cornelisz van den Berch that he has purchased of him the house, barn, [hay]rick and fences erected on the land of the plantation by him hitherto occupied, standing and lying in the colony of Rensselaerswyck on this side of Betlehem.” The farm was at the time occupied, not by Marten Cornelisse, but by Thomas Coninck, who in 1663 agreed with Gysbert Cornelisse about disposition of the farm’s harvest. 26

Based on information from nineteenthcentury historian Jonathan Pearson, Dunn assumes the seller of this property was Marten Cornelisse van Buren. She also supposes that “this side of Betlehem” equates to “on the east side” of Bethlehem, or in other words, across the Hudson on lower Papscanee Island or the hills east of the island. 27 Both conclusions, however, are suspect.

Looking first at the location of the farm in question, there is little likelihood the deed refers to Papscanee Island or anything on the east side of the river. Beverwijck (later Albany) was, in 1662, the administrative seat for both the city and Rensselaerswijck colony. Even though neither the name of the administrator who recorded the sale nor the location where the transaction took place appear in the deed, it is far more likely it occurred in Beverwijck than on the remote east side of the Hudson. A more reasonable interpretation is that “This side of Betlehem” indicates Marten Cornelisse’s farm was between Bethlehem and Beverwijck on the west side of the river.

Secondly, the timing is off for thinking Van Buren had control of property and ownership of buildings and other structures in 1662. An orphan raised on Teunis Dirckse’s farm, he was only in his early twenties at the time and had not yet attained status as a farm lease holder. During the year 1662, he learned he and his siblings stood to receive an inheritance from a proverbial rich uncle back in the Netherlands. That knowledge, however, came in August, three months after the sale of the farm buildings to Gysbert Cornelisse. 28 Also during that year (1662), according to genealogical resources, Marten Cornelisse married Marritje Quackenbush. Newly married and with little or no assets as he started out on his own, it is highly unlikely he had at that time leased a farm from the Van Rensselaers as well as accumulating his own personal equity in a farm house, barn, and other structures to give him the right to sell them. Records indicate, to the contrary, that Van Buren’s first position as a head farmer came sometime after partners Volkert Jansen Douw and Jan Thomas Witbeck purchased half of Constapel’s Island from the estate of the late Andries Constapel in 1663. Needing a farmer to manage this land, they selected

20 Dunn “Hoogebergh,” 15. 21 VRBM, 815, 837.

22 MCR, 142.

23 VRBM, 770. Teunis Dirckse also served as surety for Michiel Jansen in legal action brought against the latter by Van Slichtenhorst (MCR, 34). Later on, Teunis Dirckse’s son Dirck Teunisse married Michiel Jansen’s daughter Jannetje. 24 Dunn “Hoogebergh,” 15.

25 VRBM, 762, 762n.

26 ERA, 3:157, 253.

27 Jonathan Pearson, Genealogies of the First Settlers of the Ancient County of Albany from 1630 to 1800 (Albany, 1872), 116; Dunn “Hoogebergh,” 17.

the young Van Buren as the lessee. 29

Another important point is the presence of Thomas Coninck. He is identified as leasing the Marten Cornelisse farm buildings purchased by Gysbert van den Bergh in 1662, with Coninck continuing to reside there during the harvest of 1663. As noted above, Marten Cornelisse van Buren was on the lower rung of the Rensselaerswijck/ Beverwijck socioeconomic social ladder. It is unlikely he would have held the position as a lessor at this time when in the context of the next several decades he remained a lessee, first on the Constapel’s Island farm and immediately following that on a farm leased from Gerrit Teunisse. 30

So who, then, was the Marten Cornelisse who sold the farm structures to Gysbert Cornelisse in May of 1662? Van Laer provides the answer in a footnote regarding the Van Buren inheritance. “Marten Cornelisz, has by Pearson and other writers been confused with Swarte Marten, or Black Marten, who from the mark he makes is readily identified with Marten Cornelisz van Ysselsteyn, one of the proprietors of land at Schenectady in 1663.” 31

It is interesting that Marten Cornelisse van Buren also had a nickname related to his physical appearance. Whereas people called the dark-complexioned Van Ysselsteyn “Black Marten,” some sources refer to Van Buren as “Marten Cornelisse Vlas” denoting his flaxen-colored locks and fair skin, not unlike his famous descendant President Martin Van Buren. 32 As Van Laer notes, later historians and genealogists have tended to conflate the two Martens based primarily on Pearson, and this conflation has included the incorrect assumption it was Marten Cornelisse van Buren rather than “Black Martin” who was in position to sell farm buildings on the west side of the Hudson north of Bethlehem.

Up on his hilltop farm, Gysbert Cornelisse apparently had the same difficulties as his predecessor Michiel Jansen in coaxing crops from his fields. A tangential reference to a 1677 agreement between then colony director Nicholas van Rensselaer and Pieter “The Fleming” Winne mentions that Gysbert Cornelisse at that time had been using some additional cropland near the lower end of Papscanee Island. Van Laer, in an abstract of this agreement, reports, “The director of the colony leased to Pieter Winne a small piece of land on the east side of the river, opposite Bethlehem, formerly used by Pieter Quackenbush, and two small islands, lying south of the island then used by the farmer of the Hoogebergh.” 33 Whether this denotes Gysbert was using the two islands or the south part of the island— presumably Papscanee Island—is not clear, but it does show he was eager to use rivernourished cropland to supplement his own less-bountiful fields on the “high hill.”

It is little wonder, then, that after the devastating fire on the Hoogebergh farm across from Albany in 1679, the aging Gysbert Cornelisse left that location and instead leased the lower end of Papscanee Island. His presence there was documented within the next couple of years when he found himself in a dispute with the other farmers on the Island, Cornelis Teunisse at the upper end, and partners Volkert Douw and Jan Thomasse in the island’s middle. These neighbors to the north apparently did little to prevent their cattle from freely wandering through Gysbert Cornelisse’s grain fields. In May 1681, he sought assistance from the court, which ordered the neighboring farmers to construct the needed fences. 34

Following Gysbert Cornelisse’s relocation, there seems to have been no further attempts to farm the original farm aende Hoogebergh (on the high hill) across the river from Albany.

Clues to Original Location. Sander Leendertse Glen’s harvesting of trees on the Bergh in 1660 (reference 4) provides another clear indication that this hill, and not just the farm on the hilltop, was within easy visibility of Fort Orange. Glen’s association with Hoogebergh seems to have been limited to this cutting, probably mill

Flaxen Hair—The late New York Archivist Arnold Van Laer identified two seventeenthcentury residents of the Rensselaerswijck-Beverwijck area named Marten Cornelisse. One had the surname van Ysselsteyn and was known as “Black Marten.” The other was a Van Buren. He was also referred to as Marten Cornelisse Vlas, indicating he had a lighter, flaxen-colored appearance, not unlike his famous great-great-grandson, President Martin Van Buren.

ing the trees into valuable building lumber. Glen was later associated with the new village of Schenectady along the Mohawk River. As Dunn suggests, this reference clearly precludes lower Papscanee Island as a possible Hoogebergh location at that point in time, as it was located well south of the fort.

Certainly the most important clue for locating the Hoogebergh farm is the fire that caused Maria van Rensselaer such concern in the fall of 1679 (reference 7). Maria’s letter strongly indicates Hoogebergh was within easy visibility of Albany in 1679 when the farm buildings burned in such a spectacular fire. A blaze on lower Papscanee five miles to the south would not have been so remarkable to Maria and the residents of Albany, if noticed at all. As with the Glen tree-cutting reference, the location of the original Hoogebergh and the farm that adopted that name had to be directly across from Beverwijck/Albany at that time. 35

29 ERA 3:435. This lease was dated December 27, 1675, and includes both the Douw/Witbeck half of the island plus the other half owned by Teunis Cornelissen Spitsenberg. A line in the lease notes that “the lessee shall use as much land there as he has hired for some years.” 30 ERA, 3:515–16. Marten Cornelisse and Gerrit Teunisse had been childhood companions growing up on the Van Vechten farm.

31

32 VRBM, 181n.

ERA 1:515–16.

33 CMVR, 28n.

34 MCARS, 3:119, 352.

35 Another indication that the fire occurred across from Albany comes from court records a month or two later when Albany officials discussed deficiencies in the community’s fire-fighting abilities. MCARS, 2:460–61.

The Hoogebergh Fire – When Albany residents witnessed a fire on the Hoogebergh farm in November 1679, it could hardly have been at the lower end of Papscanee Island, some five miles to the south, where the house today called Hoogebergh now sits. As seen here, only the top half of today’s 42-story Corning Tower in Albany’s Empire Plaza (far left) is visible from the river near the house (far right).

So where could Hoogebergh have been in relation to Van Rensselaer’s original planning concept and during the time period including the tree harvest and the spectacular fire? Modern topography has changed the landscape to some degree in today’s city of Rensselaer. Some of the lower end of Mill Creek, for example, is now situated under pavement. But the major features— the river, the flatlands along the river, and the ridge rising to the east—are still much as they were in 1638. When you cross the Dunn Memorial Bridge and continue along Routes 9/20, you soon find yourself climbing a hill that plateaus near the entrance to the University of Albany’s east campus. From there, the road continues along the plateau south-southeast to the current East Greenbush town center. A road connecting this road back to the River Road (Route 9J) is known as Hayes Road. The area within the triangle formed by these roads and the river roughly mark the early dimensions of Greenbush and Rensselaerswijck’s early east-shore farming community. Most farms were along the river, and it was the forested hill behind them that came to be known as the Hoogebergh. At the northerly end of this hill today is the college campus that is the most likely site of Michiel Jansen’s and Gysbert Cornelisse’s original Hoogebergh farm.

Still today, the vantage point of this locaSpring 2020

tion provides impressive views of the city of Albany across the river. From here, it would have been easy for Jacob Lambertsen to watch Sheriff Van Slichtenhorst cross the river and proceed along the road to the farm. And blazing farm buildings at this location would have been clearly visible to the denizens across the river, especially after the autumnal defoliation in November 1679.

As later patroonship directors expanded Rensselarswijck into new riverfront neighborhoods along the flats north of Albany, in the area then known as Lubberton’s Land near present-day Troy, and in the area inland from Castle Island known then and now as Bethlehem, additional farms back from the river were less desirable and therefore slow in being developed. This provided Gijsbert Cornelissen van Broecklen liberty to continue expanding his Hoogebergh farm by clearing and sowing additional crop fields along the ridge. When Gerrit Teunisse, who received a grant of land in 1677 from Gov. Edmund Andros, leased acreage of that patent to Jan Roose in 1678, he identified it as land along the ridge “behind” the Hoogebergh farm (reference 6). From the vantage point of the farm on the northern end of the ridge, the land “behind” the farm would have been uncleared land to the southeast of Hoogebergh’s fields.

But what about that crystal? If this is truly the site of the Hoogebergh farm, where did Michiel Jansen discover the gemstones that excited the imagination of Kiliaen van Rensselaer? As it turns out, there is a small stream bordering the northern edge of the site. This brook drains runoff from the upper slopes of the ridge, washing any sentiment or loosened stones down into the old Greenbush village area below, where significantly it empties into the larger kil at the bottom of the hill—the same Mill Creek where the crystal was first discovered and announced by Governor Minuit.

Sources of Confusion. If Hoogebergh was directly across the river, how did such esteemed researchers as Van Laer and Dunn come to reject that as it’s original location? There are, after all, a couple of references (numbers 5 and 8) that at face value specifically place the farm on Papscanee Island in 1666 and 1696, respectively. A critical look at these two primary source references, however, shows there are issues with each.

A research tool known variously as critical reading or textual criticism is a technique for analyzing and interpreting written texts, and often reinterpreting previously accepted understandings. As defined by linguist and writing instructor Daniel J. Kurland, critical reading is “an examination of those choices that any and 15

View Across the River—The grounds of the University of Albany’s east campus afford clear views of the Albany skyline. With the brush cleared on the banks of the hill, 17th century residents would have had an equally clear sightline down to the river and the old Greenbush ferry landing. From the Albany side, residents easily would have witnessed the spectacular fire that destroyed the Hoogebergh farm buildings in 1679.

all authors must make when framing a presentation: choices of content, language, and structure.” 36

Historically, the technique dates back at least as far as Talmudic scholars of the late second century CE who used hermeneutics to debate, interpret, and document the meaning and intent of the Hebrew Bible. Perhaps the most significant critical reader in Western civilization was religious reformer Martin Luther, who devoted much of his life’s writings to his retranslation and reinterpretation of the Christian Bible in the sixteenth century. 37 Over a century later, philosophers like René Descartes and Isaac Newton adapted the concept of religious exegesis to the secular disciplines of physiology, mathematics, the sciences, and others. It was critical thinkers like John Locke, David Hume, Voltaire, and Benjamin Franklin who remolded political theory into the foundation of the eighteenthcentury Age of Enlightenment and the revolutions in America and Europe.

Religion has continued to be a primary source of critical interpretation. One noteworthy early example was Thomas Jefferson, who famously re-edited the four New Testament gospels and removed sections he believed historically inaccurate to compile a single narrative more closely in tune with Jesus’ original teachings. 38 The “quest for the historical Jesus” entered the twentieth century with studies by Albert Schweitzer and, later in the century, a group of scholars including Robert Funk, John Dominic Crossan, and Marcus Borg known collectively as the Jesus Seminar. Using established criteria—such as author bias and religious agenda, chronological proximity between 36 Daniel J. Kurland, “How Language Really Works: The Fundamentals of Critical Reading and Effective Writing,” at http://www.criticalreading.com/critical_reading.htm, retrieved 7/7/2019.

37 See R. Larry Sheldon, “Martin Luther’s Concept of Biblical Interpretation in Historical Perspective,” doctoral dissertation for George Fox University, 1974; Carl L. Beckwith, ed., Martin Luther’s Basic Exegitical Writings (St. Louis, 2017). 38 Thomas Jefferson, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth Extracted from the Four Gospels, Charles M. Province, ed. https://www.nationallibertyalliance.org/ files/docs/foundingdocs/Jefferson%20Bible.pdf, retrieved 7/11/2019.

Crystal Runoff—Over the centuries and millenia, streams like this one on the east-northeast end of the Hoogebergh ridge drained cloudbursts and snowmelt from the Taconic foothills along the east side of the Hudson River. In the process, the stream eroded chunks of quartz crystal, dumping them into the larger Mill Creek, where in the 1630s they excited the hopes of Amsterdam jeweler Kiliaen van Rensselaer.

events and the writings that relate them, and conformity with established theologies— they consider passages of the New Testament and vote on whether they represent historical authenticity or interpolated religious dogma.

Other independent religious scholars, including E. P. Sanders, John Meier, Bruce Metzger, Bart Ehrman, and others, have also advanced the discipline of biblical textual criticism to include compositional and reproduction errors among the ways early texts have become distorted over the centuries. In his book Misquoting Jesus, Ehrman studied differences between all known texts of the New Testament books up until Guttenberg’s invention of moveable type. He found an amazing statistic: there are more discrepancies between the texts than there are words in the New Testament. 39

Many of the tools employed by these biblical textual critics are useful in nonreligious branches of history as well. These include: 1. Multiple attestation—when a historical event is documented by two or more independent sources. 2. Embarrassment—when a historical source admits something that would be considered embarrassing to him or her; such inclusions are considered to have increased historical accuracy. 3. Contextual conformity—whether historical statements fit the location and time period in which they are given. 40

These criteria deal primarily with texts that underwent multiple stages of copying by professional scribes in the centuries prior to printing. To these we need to add consideration of errors and discrepancies made during the processes of composing, editing, transcribing, and translating in the post-Guttenberg period. Examples of this added criterion, which we can call 4. “compositional errors,” include misspellings, grammar errors, parapraxes or “Freudian slips,” and, in the days before typewriters and electronic word processing, edits and insertions that sometimes unwittingly alter the original meaning or intent. 41

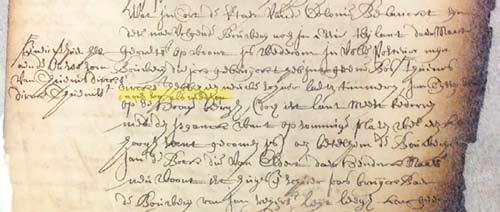

It is criteria 3 and 4 that are important in our study of Hoogebergh’s location, looking first at Jeremias van Rensselaer’s 1668 description of efforts undertaken in the two years since the major river flood of April 1666 (reference 5). A look at the original manuscript letter shows the writer edited one error in his original by making

Composition Error—When Jeremias van Rensselaer realized he had made an error in composing a letter in 1668, he made the edit highlighted in this image. In his haste, he didn’t notice that in correcting one error, he inadvertently made another, making it seem that a river flood two years earlier had deposited sediment on top of the Hoogebergh hill.

a correction that, uncaught by him, created a new and different error.

Jeremias, in explaining to his brother Jan Baptist which farms had survived, noted these included “Jan Tyssen’s farm on the Hooge bergh (although the land is largely spoiled by the ice drift, as in some places the sand deposited on it is knee deep).” From various other sources, we know that in 1666 Jan Tyssen Hoes managed the farm originally leased to Cornelis Maasen van Buren at the upper end of Papscanee Island, well north of the later Staats home at the island’s south end. 42 When Jeremias noted his mistake, he inserted the words “as is also that” before the words “on the Hooge bergh” in an attempt to correct it. His intent was to explain that both Jan Tyssen’s farm (on the island) and Gysbert Cornelissen’s farm “on the Hooge bergh” remained in operation. In making the correction in his draft, however, he failed to relocate the parenthetical explanation of deposited sand back to Jan Tyssen’s farm, instead making it look like the river flood illogically deposited silt instead on the “high hill.” 43

A similar compositional mix-up occurs in reference 8, where it appears the deed is referring to a “farm called the Hoogebergh.” An alternate reading of the legalese deed language, however, shows that Hoogebergh here is not the name of the farm, but the name of the “Hill just behind said land which lies to the eastward of the farm.”

Confusion often arises when multiple prepositional phrases are stacked within a sentence, leaving the reader wondering what each phrase refers to. We commonly call such occurrences misplaced modifiers. Such is the case here, where there are five such modifying phrases: 1) “to the foot,” 2) “of the Hill,” 3) “behind said land,” 4) “to the eastward,” and 5) “of the farm.” In this case, the string of phrases leaves it in doubt as to whether the name Hoogebergh refers to the farm, as has been widely accepted, or rather to “the Hill.” If you take out the last three of these phrases, the sentence then reads: “easterly to the foot of the Hill called the Hoogebergh.” Or stated a different way, if we reposition the confusing phrases, it becomes “easterly to the foot of the Hill called the Hoogebergh just behind said land which lies to the eastward of the farm.”

Supporting evidence comes when considering the criterion of textual continuity. References 1 and 2 are termed in such a way to indicate Hoogebergh was the hill on which the farm was located rather than to the farm itself. From reference 4, we

39 Bart Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (San Francisco, 2005), 10, 90.

40 For a discussion on these criteria, see the section on “Methods for Establishing Authentic Tradition” in Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth (Harper One, 2013), Apple iBooks edition, chapter 8, “Finding the Jesus of History.” 41 Over the past three decades, this criterion has expanded to include autocorrect blunders from computerized text editors.

42 Jan Tyssen came to manage the upper Papscanee Island through his marriage to the widow of the previous lessee, Clase Cornelisse van Voorhout (CJVR, 271, 406; MCARS, 1:68). It is a notable coincidence of history that both the paternal and maternal immigrant ancestors of President Martin Van Buren worked the same farm at the top end of Papscanee Island. 43 For further explanation of this composition error, see my earlier essay “The Great Flood of 1666” in de Halve Maen 89:1 (Spring 2016).

Will the Real Hoogebergh Please Stand Up—Although various researchers over the years have concluded the relatively low prominence overshadowing the Staats house is the original Hoogebergh, it seems unlikely when it is itself overshadowed by the much higher ridge just to the east.

see that Hoogebergh (or in this case, just the Bergh) continued to be the generally understood name of not just the farm, but the ridge on which the farm was located. With this in mind, it is more likely that when Jeremias van Renssealer recognized and confirmed Gerrit Teunisse’s patent, the name Hoogebergh as mentioned in the reference 8 deed refers to the mainland hill and not to the lower Papscanee farm. Added to this is that the deed’s obvious purpose is to define the Gerrit Teunisse patent, not the Staats farm.

Putting this all together, the geographic feature called Hoogebergh by the seventeenth-century Dutch starts at the site of today’s college campus and continues southerly to the Clinton Heights section of East Greenbush and thence along today’s Ridge Road to its terminus at Hayes Road, reaching a height of over 500 feet at what is now known as Grandview Hill. The ridge then continues at a lower elevation down to Castleton-on-Hudson.

Migration of the Name. So if the 1668 reference to Hoogebergh’s flood recovery was a composition error and the 1696 reference is a misinterpretation of misplaced modifiers, how then did the name Hoogebergh become associated with the Staats family home on Papscanee Island? Shirley Dunn offers one suggestion that has great merit. In her essay on Hoogebergh, she suggests that applying the name of Gysbert Cornelisse’s burned farm to his new location on the island touched the Dutch-Americans’ sense of humor. The relatively low knoll on the island was certainly much less imposing than the high hill on which he had previously farmed, and dwarfed by the majestic 4,000-foot Catskills visible down river. But it was high enough for the boorish jesters of the day to joke about. “Gysbert Cornelise brought the name Hooge Berg with him from his high hill,” writes Dunn. “The humor of this contrast would be apparent to all.” 44

Using the same textual criticism tools as before, this hypothesis passes the test of contextual conformity. Seventeenthcentury Dutchmen and women were quick to attach humorous nicknames to people and places, sometimes in good humor and other times maliciously. A local troublemaker named Claes Teunissen, for example, was branded with the name Uylenspeigel after the notorious German practical joker Till Eulenspiegel. 45

If someone had a notable physical feature, it was fair game for the nightly tavern crowd to make it the focus of a nickname. Cornelise Segerse van Voorhout and his sons had the nickname “Wip” appended to their given and patronymic names, Seger Cornelisse Wip, Klaes Wip, and Kees (Cornelis) Wip. Van Laer theorized this name derived from their distinctive upturned noses. “The word also occurs in the term ‘Wip-neus,’ meaning a tilted, tipped-up nose and may, in that sense, have been applied as a nickname for father as well as the son.” 46 A similar explanation seems to be the root of the name Groesbeck, which lampoons not only the largebilled evening grosbeak in your backyard, but also a Hudson River family.

Another well-known example of nickname humor comes from a slanderous invention in 1655 giving satiric names to several homes in Beverwijck. “Cornelis Vos,” explains author Carl Carmer, “apparently applied nicknames so appropriate to the houses of various respected burghers that the whole town was bandying them about and getting many a mean laugh out of it. He had called one house The Cuckoo’s Nest and another The House of Bad Manners. One he had named Birdsong after a famous disorderly street in the town of Gouda in Holland, and another The Savingsbank because of its miserly inhabitants. Mr. Van Rensselaer’s house he called Early Spoiled and Mother Bogardus’s The Vulture’s World, and he had entitled the town eating house The Seldom Satisfied.” 47

It is perfectly in context, then, that about 1680, the mischievous Hudson Dutch would have transferred the name Hoogebergh, along with the farmer, from its original location to a site marked by

44 Dunn “Hoogebergh,” 17. Although Dunn has a different theory of the location of the original Hoogebergh and the timeframe of the move, the point about the humorous reaction of the populace is nonetheless valid.

45 ERA, 1:423, 2:162; MCR, 173.

46 James Brown Van Vechten, Van Vechten Genealogy (Detroit, 1954), 330; CJVR, 228, 271; A. J. F. Van Laer, Minutes of Fort Orange and Beverwyck 1657–1660 (Albany, 1923), 39; In CJVR 228, Van Laer incorrectly identifies Kees Wip as Seger Cornelisse; as Kees is the common diminutive nickname for Cornelis, it is clear that Jeremias is referring to the father Cornelis Segerse by his nickname, and the son Seger Cornelisse by his given name. This is also consistent within the context of the passage. 47 Carl Carmer, The Hudson (New York and Toronto, 1939), 37; Charles Gehring, trans. and ed., Fort Orange Court Minutes 1652–1660 (Syracuse, 1990), 173.