OCTOBER 17–NOVEMBER 16, 2024

One of the most compelling qualities that attracted us to Charles Cajori’s oeuvre is his retention of the human form. In the heated throes of the Abstract Expressionist movement of which he was an active participant, Cajori deviated from the trends, revealing his individuality and inventiveness. Postwar figuration has always been a particularly interesting aspect during this lively period in American art history. However this is not to exclude Cajori’s totally non-objective compositions—some of which are presented in this exhibition. They too are a masterful mix of form, color, and spatial balance and certainly stand alone as strong examples rivaling any of his contemporaries. Yet some of his most engaging paintings and drawings combine a lively and bold style of abstraction with the figural.

Though Cajori utilized the figure it was always presented in a non-traditional, experimental manner. One feels passion and dynamism in his compositions—he was unconventional in the way he incorporated these forms making them an integral part of the larger pictorial space. He explored ways in which humans fit into their environments with explosive vigor, and his ability to create a painting filled with rhythm and light in such an unexpected way is remarkable. His resume is similarly notable. Not only was he a founding member of the Tanager Gallery, an important artist collaborative from the 1950s through the ’70s, he was also co-founder of the celebrated New York Studio School in 1964, an institution which still exists today. An influential teacher on both the East and West Coasts, Cajori befriended a pantheon of contemporary artists, and received much acclaim during his lengthy career.

Believing in the significance and broad appeal that Cajori’s work offered, we were especially gratified in securing representation of the artist’s estate. Working with Barbara Grossman, head of the estate, has been a delight. Being an accomplished painter herself, Barbara brings an understanding of the intricacies of the artworld, and has been supportive and helpful at every juncture. As she shared a long life with Cajori, her personal anecdotes and critical analysis of his work prove invaluable. Immeasurable appreciation is extended to John Seed for his thorough biographical account of the artist’s life and his examination of the complexities of Cajori’s work, revealing his own art historical expertise of this subject matter. And for her customary diligence that always exceeds expectations, we acknowledge Kara Spellman for her contributions to this project.

Part of what continues to drive us to do what we do in the gallery is the joy and satisfaction felt when discovering, or re-discovering, the work of an artist that is exceptional and exciting, whose work has quality and gravitas. Certainly that is the reaction we experience with the work of Cajori. Not only visually striking, his paintings also have an elemental substance—that unique special ingredient that separates him from his peers. His paintings bring to light a thoughtful and courageous artist who did not simply follow a trend, but successfully forged his own original practice.

Hollis C. Taggart

Debra V. Pesci

The painter Charles Cajori is most often referred to as a second generation Abstract Expressionist. That categorization, which fits nicely into the standard framework of Postwar American art, barely scratches the surface of the artist’s nearly seven-decade long oeuvre and its rich, idiosyncratic development. It is true that Cajori opened his career in New York City when Abstract Expressionism was reshaping American art and that some of its heroes were his neighbors and friends. Their influence on his art was profound and he did make abstract—or nearly abstract—paintings early on. But labeling Cajori an Abstract Expressionist or an action painter, as critic Lawrence Campbell once did, feels like shorthand.

Cajori needed a something—a landscape, a figure, or a pair of figures—as the scaffolding for his artistic process. “No one could make your figures out, Cajori,” his friend Lois Dodd once recalled, “and no one could make mine out; but we were figurative.” A serious artist for over seven decades, Cajori was a hybridizer who relied on both observation and improvisation, exploring the intricacies of figure-ground relationships and pictorial space. A connoisseur of overlaps and interstices, he worked in the slipstream of Abstract Expressionism, carried forward by its epic force, then carried towards his own explorations.

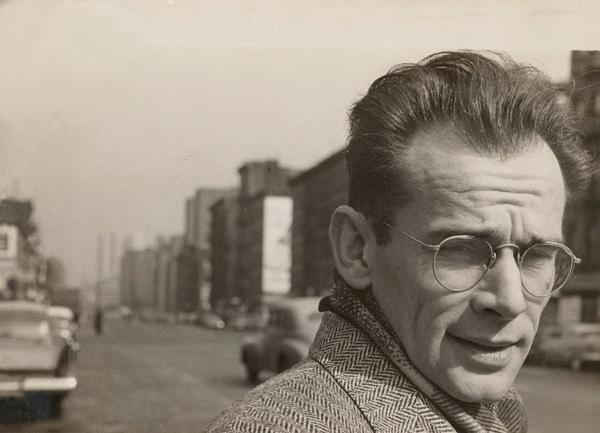

Fig. 1

Cajori, circa 1960, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

The son of Florian Anton Cajori, a Swiss-American bio-chemist who taught in the Medical School at the University of Pennsylvania, and Marion Huntington Haines Cajori, a pianist and educator, Cajori grew up in the western suburbs of Philadelphia. As a teenager he made frequent visits to the Philadelphia Museum of Art where he was drawn to the John G. Johnson Collection of Sienese painting. Musical and artistic, he played the drums and piano and painted a mural in the auditorium of Radnor High School. At

the age of eighteen he took a summer course with the artist and illustrator Boardman Robinson at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, then spent two years at the Cleveland Art School before being drafted into the Air Force. Cajori remained in the United States during his three-and-a-half years of military service and was discharged in 1946.

Supported by G.I. Bill benefits, Cajori enrolled in Columbia University’s newly established School of Painting and Sculpture and School of Dramatic Arts, where he took classes through 1948 but did not earn a degree. He had been exposed to European modern art in the form of a Picasso retrospective he had seen at the Museum of Modern Art in 1940 but his student work still resembled American scene realism. Soon after arriving in New York Cajori went to the South Street Ferry, sat on the curb, and painted a watercolor of a building and nearby slip that led to a spatially complex oil painting. A “hole” that he perceived in that early painting opened up some of the philosophical questions about space and representation that would occupy Cajori for the rest of his life: “It made me question the nature of perception and of painting and finally how the world was made and how it might be represented.” All that from a young man who had not yet cared for the work of Paul Cézanne—later an important influence—who he thought of at the time as “a cold dish of tea.”

Mentored at Columbia by John Heliker, a representational painter who had been involved in Social Realism, Cajori was awarded scholarships to attend 1947 and 1948 summer sessions at the verdant 350-acre Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. The faculty he encountered at Skowhegan, included its founders, Henry Varnum Poor and visiting faculty members Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Karl Knaths, William Zorach, and Marguerite Zorach, who practiced forms of modernism derived from European prewar influences. While Cajori studied in Maine—painting figures and landscapes and dabbling in fresco—a revolution in Postwar American painting was brewing. Jackson Pollock made his first drip paintings in 1947 and Philip Guston, a visiting faculty member that same year at Skowhegan, completed his first abstractions.

In his 1947 essay lionizing Jackson Pollock, “The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture,” the critic Clement Greenberg wrote that in downtown New York City, “The fate of American art is being decided—by a few young people, few of them over forty, who live in cold-water flats and exist from hand to mouth.” By the late 1940s, Cajori was part of that scene, living and painting in a top floor loft on East Tenth Street that he had sublet from his professor Heliker for fifteen dollars per month. Since there was no kitchen, Cajori ate sandwiches at the Automat or paid ninety cents for a hot restaurant dinner when he was feeling flush. At the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village, he could indulge his love of jazz. He was, his guitarist friend Bill Frisell recalled, a “beatnik guy who wore jeans and tennis shoes.” After the birth of his daughter Marion in January of 1950 Cajori landed a job at a private Catholic university in Baltimore—he commuted by train—and would go on to teach for fifty-six years.

Fig. 2

Franz Kline and William de Kooning, circa 1955–60, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Untitled, a two-foot-tall oil on canvas from 1950 (pl. 1), presents Cajori at his most abstract. Painted before he turned thirty, it amalgamates competing forms and energies into a kind of visual jazz. The scion of a family that valued order—his Swiss grandfather wrote the first history of mathematics—Cajori, the rebel, reveled in abstracting the vitality and chaos of his surroundings and experiences. Hints of light, landscape, and architecture jostle and tumble across the impasto surface of the canvas, weaving themselves into a quilt of sensations and associations. His palette is rich and varied: zones of Indian red, burnt orange, white, yellow, ochre, forest green, and olive interspersed with blasts of blue. It is the work of young man in the thrall of Abstract Expressionism, immersing himself in the expressive possibilities presented by the vanguard style.

For Cajori, who had not yet shown his work in a commercial gallery, new opportunities emerged after the artist-led Ninth Street Art Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture opened in May of 1951. Held in the basement and first floor of a condemned building, the exhibition included seventy-five artists and marked the public debut of Abstract Expressionism, featuring a number of Cajori’s Tenth Street neighbors including Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Jack Tworkov. Although nothing sold, the show had a vitalizing impact and brought attention to the rising vanguard. As Cajori later recounted, “The Ninth Street Show made it possible to exhibit without all the accoutrements and apparatus of a gallery.”

The Tanager Gallery, which opened in the summer of 1952 on East Fourth Street and then moved to a one-room storefront on Tenth Street in 1953, offered local artists a place to exhibit and exchange ideas. Founded by Cajori and four artist friends—William King, Lois Dodd, Fred Mitchell, and Angelo Ippolito—it offered an alternative to the

upscale galleries on Fifty-Seventh Street and held spirited, wine soaked openings that spilled out onto the roof and out the front door. For Cajori, who was a social being, the gallery and the surrounding neighborhood soon held more galleries and served as his art world nexus. Tenth Street became the center of lively and fractious artist community energized by arguments about art and lover’s spats. “There were so many artists there,” he recalled. “You used to walk down the street at 5 or 5:30 and meet everyone.” Innumerable studio visits, made in service to the Tanager, gave Cajori the chance to observe a burgeoning art scene.

Group shows at the Tanager often mixed the works of well-known Abstract Expressionists with those of younger artists. This curatorial co-mingling put Cajori in touch with his artistic heroes, especially de Kooning. While assembling an early Tanager group show Cajori visited de Kooning’s studio, where Woman I (1950–52, fig. 3) was still on the wall, and picked up a superb pastel of two women that he kept in his own studio for a few weeks. It proved to be a kind of talisman as de Kooning’s artistic interests and inclinations were shared by Cajori. Art historian Barbara Rose’s description of de Kooning’s “no-environment” describes the same kind of spatial ambiguity that soon appeared in Cajori’s paintings: “De Kooning’s pictorial dilemma is spatial. Contours are opened to allow flesh and environment to flow into one another, and anatomical forms themselves have been fragmented; hence there is no clear statement as to where the figure is actually located in space.”

Cajori’s large Untitled works in oil and charcoal from 1957 (pls. 2 and 4) demonstrate his inclination to interweave human figures into abstract environments. This hybrid approach, made in an era when the idea of progress in art worked against figuration, left some observers puzzled. “Cajori dissects in an impulsive manner,” wrote one New York Times critic, “what might be taken for figures.” During that same year a number of the Tanager artists began to hold regular meetings with the goal of publishing a book that would work against these critical misunderstandings by offering new, broader stylistic categories. As Irving Sandler, the Tanager’s manager, later recounted:

Those in regular attendance were Charles Cajori, Lois Dodd, Sidney Geist, Sally Hazelet, Angelo Ippolito, Ben Isquith, Alex Katz, Philip Pearlstein, Raymond Rocklin, and myself as a note taker and tabulator. They decided to avoid existing labels, such as Abstract Expressionism, Abstract Impressionism, and Action Painting, which, they claimed, were the outworn iwnventions of critics.

In one draft that emerged, Abstract Expressionists, including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Philip Guston were passive aggressively recast as “Old Masters,” while Cajori’s peers Lois Dodd, Philip Pearlstein, and Jane Freilicher fit into “Nature Observed.” Cajori, along with Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell, was part of “Nature Departed.” The book was never published, but part of the legacy of the Tanager that it recognized and supported individualism. “I think we made a real attempt to believe outside of particular modes, without the constraint of a manner,” Cajori stated.

Fig. 4

Printed invitation for solo exhibition at Tanager Gallery, New York, 1956. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

In 1958 a solo show at the prestigious Bertha Schaefer Gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street furthered Cajori’s reputation. After receiving an award for Distinction in the Arts from Yale University, he traveled to California in late 1959 to teach at the University of California at Berkeley, where he drew from the model with Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn, two founders of the Bay Area Figurative School. Although Cajori was offered a tenure-track teaching job at Berkeley, replacing David Park who was ill with cancer, he decided to return to New York. A photo taken of thirty-nine-year old Cajori in May 1960 at an opening at the Martha Jackson Gallery shows him as a bespectacled, pipe smoking professor in a jacket and tie. No longer connected with the Tanager Gallery, which would close in 1962, he had established himself as a mature artist who earned this praise from critic Dore Ashton in 1964: “The multiple echoes of form, the firm statement of relationships between void and volume fill his page without crowding—an achievement of patient diligence over years.”

Fig. 5

Printed group exhibition announcement, Tanager Gallery, New York, circa 1956. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Cajori’s art was grounded in the practice of observational drawing. While on a Fulbright grant in Italy in 1952 to 1953, Cajori hired a local working woman to pose for drawing sessions regularly, a job that surprised her neighbors. In New York he often took part in weekly figure drawing sessions organized by Mercedes Matter along with a group that consisted of Dodd, Pearlstein, Guston, Tworkov, and sometimes Alex Katz. Although his figure paintings were made without a model present in the studio, Cajori believed that drawing attuned him to a set of essential underpinnings that informed the unity of his paintings: “Drawing is, to me, the expression of that high attribute of the mind which perceives structure, which penetrates beyond the perception of the senses to the nature and cohesion of things. . . . Drawing is the abstract in painting.” In his drawings Cajori engaged with an epiphany that came to him while visiting a French hill town in which the sky seemed to press downward: the depiction of space involves a sensitivity to experience. Increasingly attentive to form and volume, Cajori also used drawing to explore the spaces between figures, which he felt had a psychological weight. Many of Cajori’s works on paper have erasures, overlaps, and re-stated contours that are the result of his persistent and probing approach.

In September of 1964, while still teaching at Cooper Union, Cajori joined the faculty of the New York Studio School. Founded by Mercedes Matter in collaboration with a group of students and faculty, it was modeled on European ateliers and emphasized traditional studio practices that resisted fluctuations in art world taste. One of its co-founders, Cajori would teach there off and on for over forty years. He brought with him a deep knowledge of art history and a host of entertaining anecdotes about the artists he had known downtown. One favorite involved de Kooning, who had given a bum some change then watched him weave through the traffic on Third Avenue while a group of the artist’s friends looked on and held their breath. When he reached the

other side safely, as Cajori would relate, de Kooning had exclaimed: “Now that’s a man who understands space!”

David Reed, a Studio School student from 1966 to 1967, studied drawing with Cajori and remembers working from live models that had been carefully situated: “In those days, every day the students could draw from two models posed together by Mercedes Matter in a way to show how they interacted spatially. The drawings were not concerned about a single figure but how the models related to each other and to the space around them.” Reed remembers Cajori as being “always very helpful, giving me advice but never telling me what to do. He was kind and modest, soft spoken and polite, and I felt that he always tried to help me achieve my intentions.” Elisa Jensen, also a student from 1989 to 1993, recalls drawing from a still life of bottles, arranged Cézanne style, that Cajori had set up during lunch break. “He was very, very passionate about looking and really experiencing the spatial tension. When he talked about the energy of the interstices between objects you could hear a pin drop.”

At Queens College, where Cajori taught between 1966 and 1986, Douglas Florian found him to be more influential than any other instructor. After Florian asked him to critique a large painting in progress, Cajori commented that “there is a thin line between design and painting” and brought him a Matisse book from his home library. Opening

Fig. 7

Cajori in his West Fourteenth Street Studio in New York City, 1962, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

the book to an image of one Matisse’s Moroccan paintings, Cajori demonstrated to Florian that the figure in the painting and the room she occupied were working against each other, creating spatial ambiguity that enriched the painting. “A painting can reveal itself slowly,” Cajori offered, “but design is instantaneous.” Lessons of this sort, demonstrating that true seeing should be connected with thought and feeling, proved invaluable to Cajori’s students. Jack Whitten, who studied with Cajori at Cooper Union in 1964, acknowledged this in an exhibition guest book: “Cajori, you helped me to see and I am thankful to you for that.”

In 1962 Cajori began quietly dating Barbara Grossman, one of his students at Cooper Union and later a co-founder of the Bowery Gallery. They married in 1967 and after the birth of their daughter Nicole in 1969 the couple moved to a rural home in Connecticut that included a barn which was converted to a studio. During their five decades together Cajori flourished: he had more than twenty-five solo shows, received more than a dozen awards and prizes, and continued teaching until 2006. He lived a long and productive life filled with admiring friends and students before his passing in 2013.

Cajori once wrote, “The artist’s idea is simply his sense of who he is. He has this one idea and he is stuck with it.” Seeing Cajori’s art and development through the lens of that statement, his lifelong interest in depicting the female figure makes tremendous sense. Robert Birmelin, a longtime friend, felt that there was a lifelong tension between formalism and eroticism in Cajori’s art. Engaged by the sexual magnetism of the models he drew, Cajori’s art layered and sublimated that attraction into aesthetic form. The female figure also allowed him to reach towards and reference broader themes of humanity and the experience of being alive. The influence of French painting—especially of Matisse—became important as he refined his forms and made more experiments with color, including the alternation of neutrals with brighter hues. Infusing all of his work was a spontaneity reflecting two of Cajori’s deep personal interests: jazz and chaos theory. His wife recalls that “the slippage of time and space was an obsession of his.”

In a 2008 statement, Cajori wrote about the idea of art as a “battlefield, strewn with dead issues.” He later referred to painting as a “turbulent arena” that offered the chance to create structure and find the balance between too little and too much. That interest in achieving balance, which underlies the dynamic interplay of form and chaos at work in his paintings, is an example of the kind of hard-won wisdom that shaped the long arc of his art and career. Art movements, Carjori realized, are swings of the pendulum, while art itself is something more enduring: the expression of universal emotions, experiences, and principles.

John Seed is a writer and painter who holds degrees in Studio Art from Stanford University and University of California, Berkeley. His writings on art and artists have appeared in Arts of Asia, Harvard Magazine, Hyperallergic, and Sotheby’s Magazine. Seed is also the author of Disrupted Realism: Paintings for a Distracted World (2019) and More Disruption: Representational Art in Flux (2023).

60

4.

72 × 75 1/2 in. (182.9 × 191.8 cm)

Cajori’s Untitled, 1957 weaves vestiges of human figures into a pulsating abstract space. The canvas, which has a vigor inspired by action painting, includes glimpses of feet, legs, shoulders, and heads breaking through a quilt of gestural brushstrokes. Its improvised color relationships and spontaneity also reflect the artist’s interest in jazz.

Untitled, 1962, which has a reduced palette of grey, green, and white, is overlaid by skeins of vigorous black lines suggesting overlapping figures. Throughout his career Cajori consistently drew from life but then painted in his studio without the models being present. When developing large scale oils like this one he relied on his memories from those in-person sessions to improvise figural elements and relationships.

Untitled, 1968 demonstrates how Cajori enjoyed developing multi-figured compositions into complex paintings, activated by intricate figure-ground relationships. The influence of French painting, especially of Matisse, is apparent in the painting’s schematized zones of glowing color.

60 × 45 in. (152.4 × 114.3 cm)

The foreshortened figure of Untitled, 1971 is seen from above, supported by the stylized forms of cushions and blankets. Although Cajori’s figures became more refined over time their settings retained an air of abstraction.

13. Untitled, 1974–78 Oil on canvas

84 × 54 in. (213.4 × 137.2 cm)

The flatness of Cajori’s earlier compositions is superseded by the architectural space in this monumental canvas. Diagonal and straight lines evoke a receding space that compliments the two models’ soft curves. Female figures, a constant in Cajori’s work, served as erotic presences that engaged the artist’s gaze and stimulated his artistic process.

1. Interview with Transfer Magazine, June 1988.

2. “On Paper” in Panel on Drawing, National Academy of Design, New York, October 21, 1999.

3. John Goodrich, “Intimist Glow, Expansive Gestures: Charles Cajori,” Artcritical, December 24, 2013, artcriticalcom/2013/12/ 24/john-goodrich-and-stephen-ellis-oncharles-cajori/.

4. Gerald M. Munroe, “Teaching Drawing: The Personal Approach of Charles Cajori,” The International Review, The Drawing Society, November–December 1979.

Charles Cajori led an extraordinary career during a critical juncture of postwar American art history. After arriving in New York in 1946, he and a small group of artists founded the Tanager Gallery on Tenth Street in 1952, which became a crucial meeting point and exhibition space for the growing New York School of artists. Cajori was also a founder in 1964 of the New York Studio School, a unique “atelier” art school that still exists today. Underpinning his painting practice were enduring concerns around space and form, and the construction of pictorial space through the architecture of color planes or what he called the “swift continuum of space.” Cajori passionately experimented with how the shifting of colors can add an urgency of rhythm and a quality of light. He called the surface of a canvas or paper a “spatial arena” or a “field of energy,” in which complex relationships and tensions arise and “undergo constant reassessment.”1 Unexpected configurations are brought into being, producing what he termed “dislocations from the ‘normative.’” Such harmony of forms, he believed, “cannot be arrived at rationally . . . It can’t be designed. It happens intuitively and is a final expression. This ambiguous, ongoing continuum reflects, I believe, something of our experience, of our difficulty incoming to terms with ourselves and with nature.”2 Painting, for Cajori, was almost a metaphysical pursuit and, as one critic put it, it “demanded an almost spiritual awareness of the process of seeing.”3 Accordingly, Cajori was particularly interested in the works of Cézanne and by what Cajori believed to be the seismic shifts in perception brought about by the artist. Cajori’s work grapples with the legacy of the French master, the former’s staccato, activated marks reflecting the idea that when we perceive and look at something, our eyes are never static.

Though Cajori drew and painted landscapes and non-representational works in the 1940s and early ’50s, his focus throughout his career remained the figure, which began to dominate his work in the 1960s. Always working within the tension between the fixed form of the figure and the flux of perceptual reality, Cajori strove to depict the human figure with a colorful expressionism reminiscent of Matisse and Willem de Kooning.

In the catalog for his last solo show in New York, the artist articulated his aesthetic philosophy:

First is the acknowledgment of chaos: its contradictions and wayward forces. Then the struggle for coherence. Not a coherence of illusion but one of time and space—of form. The mode of attack is improvisational, multileveled, and non-rational. The resulting structures may seem complete, but they contain a hint of another stage. New attacks are called for. Structures evolve endlessly.

This “struggle of coherence” that Cajori believed was at the heart of form is palpable in his paintings, with their energetic swaths of lines and color that seem to literally be struggling to take form, to cohere into a visually intelligible entity.

A gifted teacher who was a deep influence and formidable mentor to many, Cajori taught at Cooper Union from 1956 to 1965, at Queens College from 1965 to 1986, as well as at Berkeley from 1959 to 1960 alongside Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff. To students he stressed the need to forego preconceived notions of seeing and instead to see spatial relationships anew: “Look at the window,” he would tell his students, “and notice how the sky clings to the pane.”4

Born 1921, Palo Alto, CA

Died in 2013, Watertown, CT

EDUCATION

1939 Studied at Colorado Springs Art Center

1940–42 Cleveland Art School, OH

1946–48 Columbia University, New York

1947 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME

1948 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME

AWARDS AND GRANTS

2009 Jimmy Ernst Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters

2006 Purchase Prize, American Academy of Arts and Letters

2001 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship

2000 Benjamin Altman Figure Prize, National Academy of Design (and in 1995 and 1983)

1985 Ralph Fabri Prize, National Academy of Design

1984 Ranger Fund Purchase Award

1982 National Academician, National Academy of Design

1981 National Endowment for the Arts Grant

1980 Childe Hassam Purchase Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters

1979 Louis Comfort Tiffany Award

1976 Childe Hassam Purchase Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters

1975 Childe Hassam Purchase Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters

1970 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award

1963 Ford Foundation Purchase Award

1962 Longview Foundation Purchase Award, Yale University

1958 Distinction in Arts, Yale University

1952–53 Fulbright Grant to Italy

2015 David Findlay Jr. Gallery, New York

2012 David Findlay Jr. Gallery, New York Behnke Doherty Gallery, Washington Depot, CT, with Tom Doyle

2009 Rider University, Lawrenceville, NJ, with Barbara Grossman

2008 Lohin Geduld Gallery, New York

2007 David Findlay Jr. Gallery, New York

2005 David Findlay Jr. Gallery New York

2004 Lohin Geduld Gallery, New York

Wright State University, Dayton, OH

2003 New Arts Gallery, Litchfield, CT

2002 Paesaggio Gallery, West Hartford, CT

New Arts Gallery, Litchfield, CT, with Barbara Grossman

2000 New York Studio School, New York

1996 Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

1992 Central Connecticut State University, New Britain

1990 New Britain Museum of American Art, CT

1988 New York Studio School, New York American University, Washington, DC

1985 Gross-McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia

1983 Gross-McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia

1981 Landmark Gallery, New York

1980 Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, CT

Washington Art Association, Washington Depot, CT

1977 American University, Washington, DC

1976 Cincinnati Art Academy, OH University of Texas, Austin

Ingber Gallery, New York

1974 Landmark Gallery, New York

1972 Kirkland College, Clinton, NY

1969 Bennington College, VT

1965 Udinotti Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ

1964 University of Washington, Seattle

1963 Howard Wise Gallery, New York

1962 Heathcote School, Scarsdale, NY

1961 Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Tanager Gallery, New York

1960 Santa Barbara Art Museum, CA

1959 Montgomery Art Center, Pomona College, Claremont, CA

Oakland Art Museum, CA

1958 Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York

1956 Tanager Gallery, New York

1955 Watkins Gallery, American University, Washington, DC

2023 From Provincial Status to International Prominence: American Art of the 1950s, Hollis Taggart, New York

2018 Presence: Encounters with the Figure, Five Points Gallery, Torrington, CT

Richard McD Miller and His Circle, Brookgreen Gardens, Pawley Island, SC

2017 Inventing Downtown, Grey Art Gallery, New York University, NY

2013 About Abstraction, David Findlay Jr., New York

2007 Abstraction, David Findlay Jr., New York

Annual Exhibition, National Academy of Design, New York, since 1983

2006 The Figure in American Painting, 1985–2006, Ogunquit Museum of American Art, ME

Invitational Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

2005 Continuous Mark, New York Studio School, New York

2004 Transforming the Page, National Academy of Design, New York

Drawing Now, New Arts Gallery, Litchfield, CT

2003 A Fine Line, National Academy of Design, New York

2002 Abstraction to Representation, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA

Artist’s Eye, National Academy Museum, New York

Founding Five, David Findlay Jr. Gallery, New York

Decade of American Figurative Drawing, Frye Museum, Seattle

2001 Invitational Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

2000 Figurative Painting Now, 55 Mercer Gallery, New York

Jane Piper and Her Circle, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg

Figuration: Two Views, with Barbara Grossman, Wayne Art Center, PA

1999 Approaching the Figure, Marymount College, Tarrytown, NY

1998 Aspects of Representation, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC

Contemporary Selections, Silvermine Guild, New Canaan, CT

1996 Connecticut Artists Collection, Lyman

Allyn Art Museum, New London, CT

1995 Drawing Invitational, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

1994 169th Annual Exhibtion, National Academy of Design, New York

1992 Connecticut Artists Collection, CCSU, New Britain, CT

Andrews Gallery, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA

1991 Invitational, Graham Modern Gallery, New York

Biennial ’91, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington

1990 Connecticut Now, New Britain Museum of American Art, CT

1989 Quest, New York Studio School, New York

The Connecticut Exhibition, Bruce Museum, Greenwich, CT

American Collection, National Academy of Design, New York, traveling

1987 Drawing Invitational, Indiana University, Bloomingto

1986 Works of the Figure, Allegheny College, PA

161st Annual Exhibtion, National Academy of Design, New York

1985 160th Annual Exhibtion, National Academy of Design, New York

1984 Artist’s Choice Museum, New York

American Drawings, New York

Studio School, New York

1983 Connecticut Painters, 7+7+7, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT

1979 Recent Acquisitions, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

1978 Six Draughtsmen, Westminster College, PA

1977 10th Street Days, New York, traveling

1974 The Figure: 8 Artists, Landmark Gallery, New York

1971 American Drawing ’71, Iowa State University, Ames

Contemporary Figure Drawing, Glassboro State, NJ

New York Figurative Painting, First Street Gallery, New York

Group Exhibition of Tanager Artists, Roko Gallery, New York

1970 Three Artists, Loeb Center, New York

Invitational Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

1969 Five Figurative Painters, Indiana University, Bloomington Drawings of the Sixties, New School for Social Research, New York

Artists Abroad, Graham Gallery, New York, traveling Invitational Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

1968 Humanist Tradition, New School for Social Research, New York

Painting, University of Texas, Austin

1967 20th-Century Painting, Whitney Museum, New York

New York Artists, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington

Ten Drawings by Ten Artists, Indiana University, Bloomington

American Drawings, University of Washington, Seattle

1966 Drawings &, University of Texas, Austin

1965 Decade of American Drawings, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

1964 67th American Exhibition, Art Institute of Chicago

Some Paintings to Consider, Santa Barbara, CA

Festival of the Arts, American International College, Springfield, MA

1963 28th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting,

Corcoran Gallery, Washington, DC ’63, University of Kentucky, Louisville

Artist for Core Benefit Exhibition, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York

Group Exhibition, Nebraska Union at University of Nebraska, Lincoln

1962 American Abstract Drawing, Museum of Modern Art, New York, traveling

The Figure, Kornblee Gallery, New York

57th Whitney Annual, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Humanities of the 60s: Man in Modern Sculpture, Drawing & Painting, The New School, New York Group Exhibition, Watkins Gallery, American University, DC

1961 International Selection of Contemporary Paintings, Sculptures and Prints, 1961, Dayton Art Museum, OH

The Private Myth, Tanager Gallery, New York

1960 The Founding Five, Tanager Gallery, New York

1959–60 100 Works on Paper, Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston, traveling

1959 Corcoran Biennial, Washington, DC Paintings from Bertha Schaefer Gallery, Gomprecht & Benesch Gallery, Baltimore

1958 Festival of Two Worlds, Spoletto, Italy

1957 1957 Annual Exhibition: Sculptures, Paintings, Watercolors, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

University of Kentucky, Lexington

1956 Painters and Sculptors on 10th St., Tanager Gallery, New York

1955 Vanguard, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

1954 Artist’s Annual Exhibition, Stable Gallery, New York

1952 Three-Person Exhibition, with Kyle Morris and Davdi Slivka, Tanager Gallery, New York

Tenth St.,1952, Tanager Gallery, New York

1943 Third Annual Special Invitation Exhibition, Art Alliance, Philadelphia

Group Exhibition, Art Alliance, Philadelphia

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Abstracts at Pomona College.” ProgressBulletin, November 15, 1959.

Ashton, Dore. “Abstractions by Cajori Are Exhibited, Negro Painters in Downtown Show.” The New York Times, March 29, 1956.

——— . “Acceleration in Discovery and Consumption.” Studio International, May 1964.

——— . “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review.” The Art Digest 27, no. 4 (November 15, 1952).

Bard, J. “Tenth Street Days: Interview with Lois Dodd and Cajori.” Arts Magazine, December 1977.

Berryman, Florence S. “National Print Show on View at Library.” Evening Star, May 8, 1955.

Bonte, C. H. “Art Museum Offers Dale Collection; Alliance Has Variey of Openings, The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1943.

Campbell, Lawrence. “Charles Cajori at the New York Studio School.” Art in America, (May 1989).

College Eye, March 23, 1956, reproduction.

Cotter, Holland. “When Artists Ran the Show: Inventing Downtown.” The New York Times, January 12, 2017, nytimes.com/2017/ 01/12/arts/design/when-artists-ran-theshow-inventing-downtown-at-nyu.html.

Cross, Miriam Dungan. “New York Here; Shows Sophistication.” Oakland Tribune, September 27, 1959.

Dantzic, Cynthia Maris. One Hundred New York Painters. Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2006.

Dietz, Betty A. “‘International’ Exhibit Opens at Art Institute.” Dayotn Daily News, September 17, 1961.

Dreiss, Joseph. “Charles Cajori.” Arts Magazine, June 1976.

Finkelstein, Louis. “New look: AbstractImpressionism.” Art News, March 1956, ill., 37.

——— . “Cajori.” Scrap, no. 5, March 17, 1961.

——— . “Cajori: The Figure in the Scene.” Art News, March 1963.

Forge, Andrew. Cajori: Paintings 1952–1992 New Britain, CT: Central Connecticut State University, 1992.

Friedensohn, Eli. Charles Cajori: Paintings/ Drawings. Clinton, NY: Kirkland College, 1972.

Godfrey, Robert. Aspects of Representation: 9 Painters (Cullowhee, NC: Western Carolina University, 1998).

Goodman, Jonathan. “Charles Cajori at David Findlay Jr.” Art in America (January 2006).

Goodrich, John. “Charles Cajori.” Review, May 1, 2000.

——— . Charles Cajori: Four Decades. New York: David Findlay Jr Gallery, 2012.

——— . “Emphasizing Composition.” New York Sun, September 6, 2007, nysun.com/article/ arts-emphasizing-composition.

——— . “Intimist Glow, Expansive Gestures, Charles Cajori (1921–2013).” Artcritical, December 24, 2013, artcritical.com/2013/ 12/24/john-goodrich-and-stephen-ellison-charles-cajori/.

Gruen, John. “At Seven SoHo Galleries: Double-Rauschenberg, Five More.” SoHo Weekly News, December 12, 1974.

Harrison, Helen A. “The Legacy of an Artistic Heritage.” New York Times, September 16, 1990.

It Is : A Magazine for Abstract Art, Spring 1960.

Johnson, Ken. “Charles Cajori.” New York Times, April 28, 2000, nytimes.com/ 2000/04/28/arts/art-in-review-charlescajori.html.

Judd, Donald. “In the Galleries.” Arts Magazine, May–June 1963.

Kramer, Hilton. “Art: After Grooms, BMT Is Bucolic.” New York Times, May 7, 1976.

La Rocco, Benjamin. “Charles Cajori.” Brooklyn Rail, June 2005, brooklynrail. org/2005/06/artseen/charles-cajori.

Lenhart, Gary. “Interview with Charles Cajori.” Transfer 2, no.2 (Fall/Winter 1989–90).

Levy, Mervin. The Artist and the Nude: An Anthology of Drawing. New York: C. N. Potter, 1965.

Mainardi, Pat. “Charles Cajori at Landmark.” Art in America (January–February 1975).

Mellow, James R. “In the Galleries.” The Arts Digest 30, no. 6 (March 1956).

Monroe, Gerald M. “Teaching Drawing: The Personal Approach of Charles Cajori.” Drawing 1, no. 4 (November–December 1979).

Mullarkey, Maureen. “Gallery-Going Round-up.” New York Sun, November 26, 2004, maureenmullarkey.com/essays/ cajori.html.

Naar, Harry I. Grossman/Cajori: Forming the Figure Lawrenceville, NJ: Rider University Art Gallery, 2009.

Naves, Mario. “Sixteen Ways to See a Woman’s Body.” New York Observer, May 22, 2000.

O’Doherty, Brian. “Art: Downtown Displays.” New York Times, April 4, 1961.

O’Shaughnessy, Tracey. “Turbulent, Tranquil: A Painter’s Arc in Depot Exhibit.” The Sunday Republican, July 8, 2012.

“Painting, Sculpture Exhibit at Oakland Art Museum.” The Independent, September 19, 1959.

“Paintings by Cajori, Sculpture by Rocklin Displayed at Museum.” Santa Barbara News-Press, February 21, 1960.

Plagens, Peter. “Inventing Downtown’ Artist-Run-Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965.” Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2017, wsj.com/articles/inventing-downtownartist-run-galleries-in-new-york-city-19521965-review-the-good-old-days1484167779.

Porter, Fairfield. “Reviews and Previews.” Art News, April 1958.

Portner, Leslie Judd. “Art in Washington: 3 Bright New Shows.” Washington Post, May 2, 1954.

Preston, Stuart. “Abstract Roundup.” New York Times, February 7, 1954.

——— . “Six Exhibitions Here Run Gamut of Art.” New York Times, November 15, 1952.

Rachleff, Melissa. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965. New York: Grey Art Museum, New York University, New York; Delmonico Books-Pestel, 2017.

Raynor, Vivien. “Artists Champion Other Artists.” New York Times, January 30, 1983.

——— . “Bequest Blends Into a Museum’s Scheme.” New York Times, December 6, 1992.

——— . “Cajori Exhibition at Washington Depot.” New York Times, July 20, 1980.

——— . “Twenty-Two Artists Participate In Bruce’s ‘Biennial.’” New York Times, August 6, 1989.

Rooney, E. Ashley. Artists of New England Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2010.

Rosing, Larry. “Matisse and Contempary Art, II: 1970–1975.” Arts Magazine, May 1975.

Sandler, Irving. “New York Letter.” Art International (May 1961).

Sandler, Irving, and Andrew Forge. Charles Cajori: A Survey. New York: David Findlay Jr Fine Art, 2005.

Santa Barbara News-Press, March 6, 1960, reproduction.

Sawin, Martica. Cajori: Forty Years of Drawing. New York: New York Studio School, 2000.

——— . Charles Cajori: A Swift Continuum New York: David Findlay Jr Gallery, 2015.

Sawyer, Kenneth B. “‘Astonishing’ Liturgical Display At Walters.” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 1955.

——— . “Some Top Talent From New York.” Baltimore Sun, January 25, 1959.

Schuyler, James. “Reviews and Previews.” Art News, March 1956.

Secunda, Arthur. “Painting, Sculpture Complement Each Other at Art Museum.” Santa Barbara News-Press, February 28, 1960.

Sievert, Robert. “Charles Cajori.” ARTEZINE, September 2005, artezine.com/issues/ 20050901/cajori.html.

Starger, Steve. Art New England, June–July 2003.

Student Union Collection of Contemporary Art. Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest University, 2006.

“Students Give Painting to ISTC.” The Courier, March 6, 1956.

Turner, Norman. “Charles Cajori.” Arts Magazine, Apri 1981.

Ventura, Anita. “In the Galleries.” The Arts Digest 32, no. 8 (May 1958).

Wilkin, Karen. Cajori. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College, 1996.

SELECTED TEACHING

1964–2006 New York Studio School, New York

Summer 1986 Studio School of the Aegean, Samos, Greece

1965–86 Queens College, CUNY, Queens, NY

1956–66 Cooper Union, New York

Summer 1964 Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, CO

1964 University of Washington, Seattle

Summer 1961 Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

1959–60 University of California, Berkeley

1956–57 Philadelphia College of Art, PA

1955–56 American University, Washington, DC

1950–56 Notre Dame of Maryland, Baltimore

SELECTED VISITING CRITIC

American University, Washington, DC

Bennington College, VT

Boston University, MA

Chautauqua Institution, NY

Columbia University, New York

Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

Haverford College, Haverford, PA

Louisiana Tech University, Ruston

Parsons School of Design, New York

Vermont Studio Center, Johnson

Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Yale University, New Haven, CT

SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

American University, Washington, DC

Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock

Ciba-Geigy Chemical Corporation, Ardsley, NY

Cincinnati Art Museum, OH

Connecticut Artists Collection, Connecticut

Commission on the Arts, CT

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington

Denver Museum of Art, CO

Grey Art Museum, New York University

Kalamazoo Art Center, MI

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC

Honolulu Art Academy, HI

Illinois State Museum, Springfield

Lakeview Museum of Art and Sciences, Peoria, IL

Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, CT

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miami University, Oxford, OH

Mitchener Collection, Austin, TX

Modern Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

The Morgan Library and Museum, New York

National Academy of Design, New York

The Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, IL

The State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg

University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa

University of Kentucky Art Museum, Lexington

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls

Wake Forest College, Winston-Salem, NC

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Weatherspoon Gallery, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT

This catalogue has been published on the occasion of the exhibition “Charles Cajori: Turbulent Space, Shifting Colors” organized by Hollis Taggart, New York, and presented from October 17–November 16, 2024.

Artwork © Charles Cajori

Essay © John Seed

ISBN: 979-8-9902841-3-5

Publication © 2024 Hollis Taggart

All rights reserved.

Reproduction of contents prohibited.

Hollis Taggart

521 West 26th Street 1st & 2nd Floors

New York, NY 10001

Tel 212 628 4000

www.hollistaggart.com

Catalogue production: Kara Spellman

Copyediting: Jessie Sentivan

Design: McCall Associates, New York

Printing: Point B Solutions, Minneapolis

Photography: Joshua Nefsky, New York

Front cover: Cajori, Untitled (detail), 1974–78, pl. 13

Frontispiece: Cajori at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, 1964, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Page 4: Cajori, Untitled (detail), 1974–78, pl. 12

Page 36: Cajori in his West Fourteenth Street studio in New York City, circa 1960s, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Insitution

Back cover: Cajori in his West Fourteenth Street studio in New York City, 1962, photographer unknown. Charles Cajori papers, 1928–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Insitution

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY; © 2024 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (fig. 3)