23 minute read

Stay Plus’s old front desk attendant has stayed on through

behind the desk Manager shares thoughts on motel

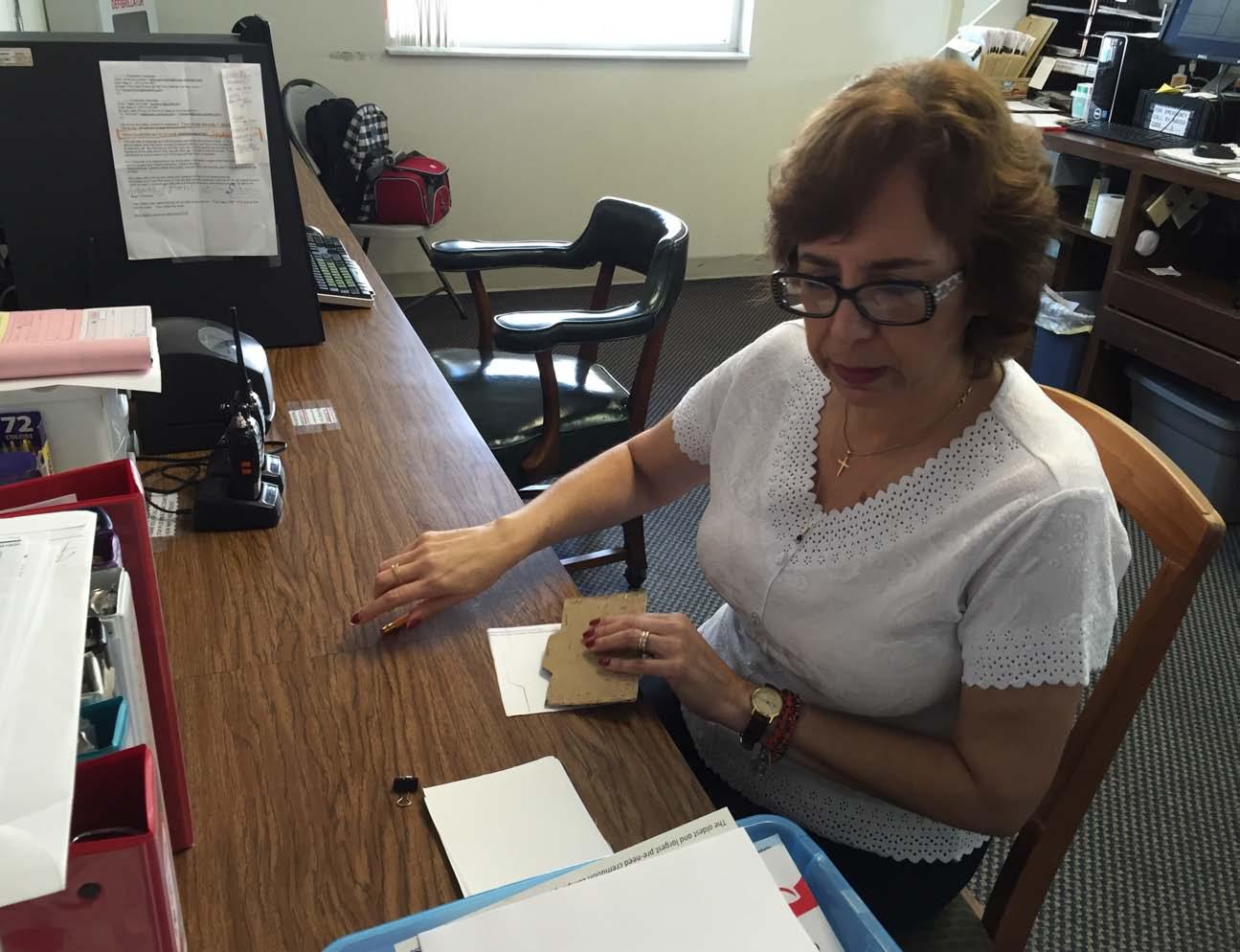

Gina Mora, front desk manager, shows how to make envelopes for the room keys.

Advertisement

Photo by Emily Miels

By Emily Miels

A bell rings as the door opens and customers enter to check in or out and stock up on supplies like snacks, drinks and cigarettes.

The phone rings and Gina Mora answers with a friendly and experienced, “Thank you for calling the Stay Plus Inn, COSAC Quarters. How may I help you?”

Look a little closer, however, and visitors may notice some differences between most motels and the Stay Plus Inn, which has been dubbed “America’s first homeless resort” by owner Sean Cononie.

It’s a different clientele that stays in the motel now, Mora said. She would know. She has worked at the Stay Plus Inn, formerly a Howard Johnson motel, for almost 15 years. Cononie took ownership of the facility earlier this year, bringing with him more than 100 residents from his former homeless shelter in Hollywood, Florida.

“Some, they don't want to take a shower, and you can smell them. It's sad,” she said, before pointing out the air fresheners she had stashed inconspicuously around the front desk to help mask the odor when needed.

There’s a note taped on the desk as a reminder to “Call 3” in case of emergency, which Mora said was sparked by a difficult guest a few weeks ago.

“(Sean) said any emergency call three immediately, because we don't know what kind of people (will come,)” Mora, who also lives on

the property, said. “If you say something wrong to them — maybe they have bipolar, maybe schizophrenia, we don't know.”

A local church also dropped off some donations one Sunday afternoon, not a typical gesture seen at most motels.

Mora, who grew up in Peru and moved to Florida in 1982, handles every call, email and guest with professionalism, frequently using her Spanish. With the buzz of the staff walkie-talkies and the occasional ring of the bell over the door, she folds recycled pieces of paper into small envelopes for the room keys during her downtime.

While the facility, its clientele, ownership and operation may have changed during her time here, Mora said the overall goal — to give the guests a positive experience during their stay — has not.

“Always we need to smile and to be very professional with the guests. And some guests they say ‘no problem,’ they take it. But a lot of people they don't feel safe or comfortable,” she said of travelers who make their way to rent a room at “the homeless resort.”

She said the housekeeping staff — Consuelo, Rosario and Enixa — works very hard to make sure the rooms are clean and orderly. She showed off the multiple sheets, written in both English and Spanish, listing the detailed cleaning directions.

She is stocked with maps of the hotels and surrounding locations, ready to assist the guests with any of their questions and needs. She makes a genuine effort to converse with the guests and get to know them, calling many by name.

“Sometimes, I pay for the people, but today I don't bring money,” she said when a resident didn’t have the change to pay for his snack.

Maybe the most important thing that has stayed the same, Mora said, is that she still loves her job.

“I love my job, and I try to help and be a better person every day while we help other people,” she said.

Stuck in a shelter One family’s story of how they arrived here despite having a home

Nick Davis (right), 14, and friend James sit outside the Stay Plus Inn lobby. He spends most days hanging around the shelter because everything else is too far away. “I can’t go out and go hang out with friends and go play games,” he said.Photo by Shannon Kaestle

By Nicole DeCriscio

Corey Davis has to go online to talk to his friends.

That’s because the 19-year-old and his family are stranded at a Florida motel.

He spends his days sleeping, gaming and sitting around.

Corey mostly sits at his mom’s computer playing a role-playing game.

He doesn’t like it here.

“There is no one my age that I can hang out with,” he said. “It’s all little kids.”

Transportation is a problem for most residents. The shelter is far away from everything, even WalMart. The only entertainment is the swimming pool and the internet.

When Corey, his mom Trina and brother Nick moved to Florida, they expected it to be a short trip to check on a sick relative. But it’s been nearly five months, and they’re still here. They’re stuck. They have a mobile home near Springfield, Illinois, they just don’t have a car to get to it. “We started calling through the phonebook and this place was listed under Stay Plus, but they said that they go according to your income,” Trina said, which was the answer for the family that lives on $733 dollars-a-month.

But the entire family shares the desire to go home.

“We’re all so homesick and Nick especially because he misses his own school and his own friends,” Trina said. “We want to be home so badly. We just don’t have the transportation.”

The lack of a vehicle is most of the reason the family cannot go back to Illinois.

A few weeks ago, they had plans to return home, but on the day they planned to leave, they received news that her godmother, who is in Jacksonville, was ill again, the other reason for staying here.

“We’re just kind of leaving it in God’s hands,” Trina said. “I feel like God led us here.”

Trina refers to the small double hotel room as income-based housing for her, her sons and her two dogs, Lilly and Trouble. Her brother, Robert, also shares the space with them.

While space is limited, she says it’s better than sleeping under a tree.

Because the family plans on making this stay temporary, Trina doesn’t see herself and her family as homeless.

“I don’t really consider myself homeless if you think about it because I have to pay rent every month, so I’m not homeless,” she said. “I’m just living here until I can get my family back home.”

While she rejects the label of homeless, she wanted to set the outside world straight – not all homeless people are drug addicts.

“The majority are people that just can’t afford to live in the real world, but they can afford to live here because the way things work is different,” she said. “They’re paying their bills every month, too. It’s just a little harder.”

In the meantime, Trina is doing what she can. She’s saving money, while still providing for her family, and praying.

“I’ve just got to have faith and be patient,” Trina said.

On the other side of the room, 14-year-old Nick gets ready to go outside with his one of his two friends here, James, who also lives in the shelter.

“I don’t talk to anybody from my school here,” Nick said.

The freshman in high school wishes that the mall was closer to the hotel.

“It’s not like I have the money to go shopping,” he said, fully aware of the financial situation his family is in, “but at least I could hang out with people there.”

He shares the boredom of his brother, Corey, and browses the Internet to pass time when he’s not hanging out with James. To him, living in a hotel isn’t what it’s cracked up to be.

“Yeah, okay, I live in a hotel, but also I don’t have as many opportunities as you,” he said. “I can’t go out and go hang out with friends and go play games.”

Reservation for one at Heartbreak Hotel

By Malorie Paine

Heartbreak was something I thought I had when I stopped talking to a guy I really liked for a few days. I was wrong.

I had never honestly experienced a heartbreaking situation until Labor Day weekend at the Stay Plus Inn, when a 5-year-old boy changed my life with a six-word question.

“Can I come live with you?” he asked.

My heart didn’t just break in that moment; it shattered into a million pieces. I have never experienced pain quite like that before, and I honestly hope that I never have to again.

This Labor Day certainly wasn’t my first time experiencing homelessness, but it was the first time I’d been asked by a perfectly sweet, innocent child to remove him from the situation he was in.

Being at the shelter wasn’t heart breaking for me, it was the fact that this little boy had no control over the situation he was in. He is 5 years old, and it’s not fair that he has to experience something so terrible at such a young age.

He’s currently living in the shelter with his mom, dad and three brothers.

I realized heartbreak isn’t when you end things with someone you like. Heartbreak is when you witness 25 children living in a motel, and you can’t do a damn thing about it.

Heartbreak is when you sit with a homeless 5-yearold for a couple of hours, and he starts to ask you about where you live and whether or not your home is a mess. This sweet little boy shattered my heart into a million pieces when he asked that one simple question.

At 24 years old, six words have never affected me quite so much. In that moment, I was fighting back tears talking to him and throughout the remainder of the day. I had to find a way to divert the question so that I didn’t have to answer it. I quickly moved the conversation back to the purple balloon he had given

me earlier that day.

No one, especially an innocent 5-year-old, should have to experience something like the homeless shelter. He didn’t ask for this situation, he has done nothing to deserve the life he’s been given. I can’t remove him from this situation, obviously. He has two parents who love him very much and who are trying to provide for him.

What shattered my heart wasn’t that he asked me, it’s that my answer couldn’t be yes. This 5-yearold boy has forever changed my heart, and I will always remember what a heart shattering feels like. By Malorie Paine

Hazardous to His Health

Mental health “I’m pretty stressed out,” Cononie says. He takes Xanax, a prescription medication for anxiety, when he really needs it.

Teeth Since he took over the homeless shelter, Sean has had eight cavities and root canals, despite brushing and picking his teeth every day.

Heart Sean’s father had high blood pressure and his mother has high cholesterol. checks his blood pressure every day. It averages 150/94 most days, he says. The national standards a panel of experts (JNC 8), recommends that people on blood pressure medications have a reading of 140/90 or below. Sean’s blood pressure during the exam was 129/92.

Abdomen Sean has a large hernia in his abdomen. He has had hernias in his groin repaired four times with mesh.

Skin Most of Sean’s body is covered with small red spots. Doctors have told him it’s everything from atopic dermatitis to broken blood vessels.

By Rachel Joyner

Amlodipine 5 mg daily – for high blood pressure Metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice a day – for high blood pressure Hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily – diuretic, to remove excess fluid and for blood pressure Zocor 10 mg nightly – for high cholesterol Asprin 81 mg daily – for heart attack and stroke prevention Percocet 30 mg twice daily – for chronic pain in back, neck, joints Percocet 10 mg six times daily – for chronic pain in back, neck, joints Xanax 0.25 mg – taken on an as needed basis for anxiety Nitroglycerin 0.4 mg – as needed for chest pain Klonopin 1 mg – as need for emergency high blood pressure Amoxicillin 500 mg – takes as needed for infections

Height – 6 ft. 1 in Weight – 358 BMI – 47.2 – Body mass index (BMI) gives an estimation of body fat based on height and weight. The higher your BMI, the higher your risk for all kinds of diseases: heart disease, stroke, breathing problems, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, some cancers and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety. According to the National Institute of Health, a BMI of 40 and above is considered extreme obesity (class III).

lungs Sean has sleep apnea and wears a CPAP machine, which helps him breathe at night. He also uses oxygen as needed. He’s probably used it twice in the last year. He has smoked about 2 packs of cigarettes per day for about 30 years.

Musculoskeletal Sean has chronic back, leg and arm pain from previous accidents and surgeries, including a torn rotator cuff. He takes Percocet as need for pain. He also has Restless Leg Syndrome, a neurological problem characterized by uncontrolled leg movements and pain.

Diet “I eat what I want when I want,” said Sean, whose diet consists of takeout meals, candy, energy drinks, and iced tea. Sean’s random blood sugar test was 153 mg/dL; a normal result is less than 200.

LEgs “When I have too many Monsters or eat Chinese food, my feet swell a lot.” Sean said his feet also swell a lot after walking around all day.

Photos by Stephanie Collaianni

16 • Homeless voice • will write for food

Rachael Joyner, RN, tests Sean Cononies blood sugar.

These are the medications Sean uses on a regular basis:

I can’t believe he isn’t dead.

I’m a registered nurse, and that’s all I could think after performing a 20-minute history and physical exam on Sean Cononie, director of Stay Plus Inn.

I’ve known Sean for seven years, since I was the first Will Write for Food editor. In that time I’ve observed his chain smoking, caffeine chugging and sleep deprivation, which I always thought sounded bad. But now that I’m a nurse, I understand that the way he lives his life could kill him.

On a typical day, Sean, 50, will consume eight to 10 Monster energy drinks, two packs of cigarettes, a case of iced tea, handfuls of candy, and a few takeout meals. Sean said he sleeps about four hours for every 30 he’s awake.

I was shocked, but Sean didn’t seem worried. “I think I’m pretty healthy,” he said.

Here’s what I found. You decide.

Note - When Will Write for Food first started in 2009, Rachael Joyner was the editor-in-chief. She now works as a Registered Nurse at a regional hospital in Boca Raton, Florida. She is also working on a Master’s degree to become a family nurse practitioner at Florida Atlantic University.

Exercise “I try to tread water in the pool every night for about 45 minutes. I haven’t been able to do it at all this week.”

preventative health Sean gets regular colonoscopies because he’s concerned about colorectal cancer.

KEEPING SEAN CONONIE ALIVE

is health caues worry, but no dedidicated staff is there to support him in everyway. Photos by Stephanie Collaianni

You’re not supposed to stick antibiotic capsules up your butt. You’re not supposed to drink eight to 10 cans of Monster Energy drink every day. And you’re definitely not supposed to pee 1 1/2 gallons of urine during a four-hour power sleep.

But Sean Cononie, owner of the Stay Plus Inn homeless complex, gets away with this because he says he has more important things to worry about.

***

The ashtray on Cononie’s desk is rimmed with six burning cigarettes – all his. In between alternating drags of those cigarettes, he gulps from a 20-ounce Monster energy drink, one of many he’ll consume in a day. Recently, he went through 20 cans in a day. Like a revolving door, his staff members walk in, sit down across from him, and tell him what’s new in their lives. Then they leave when the walkie-talkie starts chirping, but not before lending Cononie a lighter for a cig when he asks.

Only when a pause settles in a conversation, or when his walkie-talkie is silent, does he think about himself.

Pulling out multicolored bottles from a baggie, Cononie is picking out his daily dosage of medication. As he places down the pills, one by one, he lists his conditions. Sleep apnea. High cholesterol. High blood pressure. Chronic joint pain. Chronic lower-leg edema. Abdominal hernia.

He keeps these conditions at bay, taking his pills. Sometimes he does water aerobics in the pool. It helps that he has a shelter to run, so he could find projects throughout the day. But he says it’s hard to get in a routine, with what happens at the hotel.

Just two weeks ago, Cononie had to save a life. Stay Plus resident Frank, a legless, wheelchair-bound man, ate a morphine pain patch to get high. Overdosing, his body slack and mouth agape, he needed CPR, which Cononie performed until the EMTs arrived.

By Loan Le

Frank’s OK now, and he says his morphine patch, which is supposed to last three days, has run out. In his office, handing Frank another patch for his pain, Cononie warns him not to eat it.

“I don’t want to find you dead,” he says. Frank answers, “Yes, sir,” and rolls away.

He can deal with the residents, Cononie says, because “Saving a life is easy. But dealing with all this government pushback, that’s what I have to deal with. This year has been mentally challenging.”

Hollywood kicked out COSAC to “cleanse the city of unwanted vagabonds,” reported the Sun Sentinel, and ultimately Cononie was given a hand he couldn’t play. Seeing Hollywood emergency response slacking, the stigma of the shelter keeping them away, Cononie needed to move for the residents’ sake. “They deserve better,” he says.

Knowing that “he takes on too much and gets shortwinded, we take care of him,” Jeanne Cardamone says.

Cardamone doesn’t work with Cononie anymore, but she visits the low-income hotel because she misses the residents. She jokes that she and Cononie are divorced, and says she knows him inside and out. She’s there any time he needs her, because he does the same for the residents. “I don’t know where he gets the empathy. He loves them,” Cardamone says.

“I don’t even want to think about if something happened to Sean. It’d be tragic. We would be shattered, broken, lost,” she says. “I don’t think we could get anyone more empathetic than Sean.”

Mike O’Hara has worked with Cononie for seven years and followed him from Hollywood to Haines City. Like everyone, he’s seen the job’s toll on Cononie. O’Hara tells him to think about what would happen if Cononie’s health got in the way, to think of all he’s done for residents. “You only live once,” he’d say to Cononie. “It’s great that you help, but sooner or later, you have to think of yourself. You’re only promised tomorrow.”

Cynthia “Cyndi” Malvita, Cononie’s right-hand person, “since he’s already left-handed,” also notices a change in Cononie, whom she’s known since high school. It’s not just sleep apnea keeping him up at night.

In Hollywood, “he had friends and enemies, but still a lot of supporters. And people who really understand Sean,” Malvita says. “Here, they judge him and the homeless.”

Malvita makes sure he does something as simple as eating. “I don’t give him an option,” she says. She makes him smoothies with strawberries, blueberries and bananas, and sneaks in some chocolate flavor, because she knows Cononie loves it. During lunchtime the other day, she fed him sliced mozzarella, tomato, avocado, drizzled with balsamic vinegar, because she just wants him to eat.

“He’s stubborn; he’s a mule. Because he’s so passionate about what he does,” Malvita says.

Back at his desk, Cononie lights yet another cigarette. The Monster can is empty. It’s noon. Cononie shrugs when asked what keeps him going. “If I don’t fight, if we don’t keep fighting, this group will be extinguished in the future.”

Cellophane Men Two men struggle to be seen in a world that wants to forget the homeless

Everyone wants to forget the homeless, but there are two homeless men I can’t forget. ••••••

I met them four years apart—one when I was a nurse for less than a year, the other when I was a journalist for less than a weekend.

Seven years ago, I was the first editor for Will Write For Food, the program that has taken over this homeless newspaper every Labor Day Weekend (see page 3). Now I’m back with 22 alums from years past, creating another homeless newspaper.

My ideas about the homeless have dramatically evolved—and it’s what I did in between that changed them.

In 2011, I went back to school and became a nurse. Six months later, I met a homeless man named Joe Dee*. This weekend, I met another homeless man named James Geiger. Though they live 183 miles apart, their struggles are strikingly similar. They are homeless. They think people don’t see them. That they don’t matter. That they are a lost cause.

But I see them. Their stories are still so real to me; the heartbreaking details are burned into my brain.

by rachael joyner

‘My Balls Hurt’

The first time I met Dee he was rolling down the hall in a wheelchair, his cantaloupe-sized testicles bursting from his ripped khaki’s.

“My balls hurt! My balls! Will someone take a look at these balls?” he pleaded in the direction of any doctor or nurse passing by.

“No nurse wants to take care of a homeless person like that,” the night nurse scoffed as she passed me his information handoff sheet. “They don’t listen. They smell. They usually have lice, or scabies or both. They’re on all kinds of narcotic meds. Basically, they’re a walking mess. Good luck.”

Dee, a weathered 50-something, was my patient, and I was a little terrified. He came in because his testicles were so swollen he couldn’t walk. The doctor ordered an ultrasound of the area to check for hernias or masses. About 20 minutes after sending Dee down for the test, I received a call from the ultrasound technician.

“I refuse to scan this patient,” she said, screaming. “He smells terrible. He won’t even let me remove his disgusting pants.”

“Um,” I stammered, “but the doctor really needs that test done.”

“Well, unless the doctor wants to rip these filthy pants off and do it himself, I’m sending the patient back,” she said, slamming the down the phone.

The staff had been trying to force Dee to take off his dirty clothes, take a shower and get into a hospital gown for the last three days.

When Dee returned, he was ranting about how no one was helping him. That was when I decided to tell him the truth.

“Dee, I think people would take you more seriously if you took a shower. You kind of smell,” I said. “Don’t you want to get cleaned up? I’ll help you.”

I was expecting another rant. Instead, Dee quietly unbuttoned his shirt and said: “Thank you for talking to me like a person and being honest. No one does that when you are homeless.”

‘That’s For the Twist and Flexin’

My first meeting with James Geiger, 53, was brief.

(Top) Haines City EMS responded to a call for Geiger September 5, at the Stay Plus Inn after he complained about severe pain in his legs as other residents look on. (Right) Still wearing his hospital I.D bracelet, he takes off his band-aid to reveal one of his four tattoos. He says he contracted Hepatitis C while his was in jail receiving the tattoos. Photo by Stephanie

Colaianni

The ambulance rushed him to the hospital as shelter residents looked on.

“I’m a walking disaster,” he said.

He wasn’t kidding. He has diabetes, liver cirrhosis, hepatitis C and congestive heart failure. His legs are swollen, thick like a baby elephant and purple from poor circulation.

Geiger, a resident at Stay Plus Inn for four months, has been to the hospital six times in the last year. This admission was less than 24 hours. Winter Haven Hospital sent him home with three prescriptions—an antibiotic for his urinary tract infection, a diuretic to remove excess fluid from his legs and lungs, and a topical ointment for the infection in his legs.

“They discharged me after I kept everyone up all night,” he said, a mischievous grin creeping across his face. “I’ve always been trouble.”

Growing up in poverty in Polk County with an abusive, alcoholic father, Geiger quickly racked up a wrap sheet of his own. “I used to play baseball as a kid. I don’t know what happened,” he said.

At 13, he stopped playing baseball, went and bought a bag of pot and some beer and never looked back. He spent several years in jail, which is where he got hepatitis C.

“It’s called a stick n’ poke,” Geiger said, pointing to a faded tattoo on his right arm. “A guy in jail gave me four.”

He described how they used soot, baby shampoo, a mechanical pencil and a staple sharpened on the floor to make the homemade tattoos.

“I paid him $10 and 20 bags of 50-cent potato chips,” Geiger said. “It was stupid. I was young.”

Geiger dumps the contents of a turquoise duffel bag

on the table, a mess of medication bottles and personal effects. He said he takes 17 pills each day, when he has them. They’re prescribed by a doctor in Winter Haven, the next town over. He takes a taxi there every month.

“That’s for the twistin’ and flexin’,” he said, holding up a bottle of Citalopram, an antidepressant medication.

Geiger is plagued by involuntary facial and body movements. He twitches, writhes, jerks and flails— neurological damage caused by years of chronic methamphetamine use. He uses a walker to get around and falls often, he said. Then, there are the people who just stare.

“People don’t want to talk to me,” he said. “I think that they think I’m eat up. Ya know, an idiot.”

“I was supposed to die three years ago, a doctor told me,” said Geiger, who doesn’t sleep much anymore. “When someone tells you that you’re going to die, you don’t want to sleep.”

As a nurse, I knew he had only a year or two to live, but I could do something to make those years better. As a journalist, all I can do is write that. That’s why I left journalism for nursing. Maybe I can make a difference rather than simply tell a sad story. *The patient’s name and some defining details were changed to protect his privacy.