THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

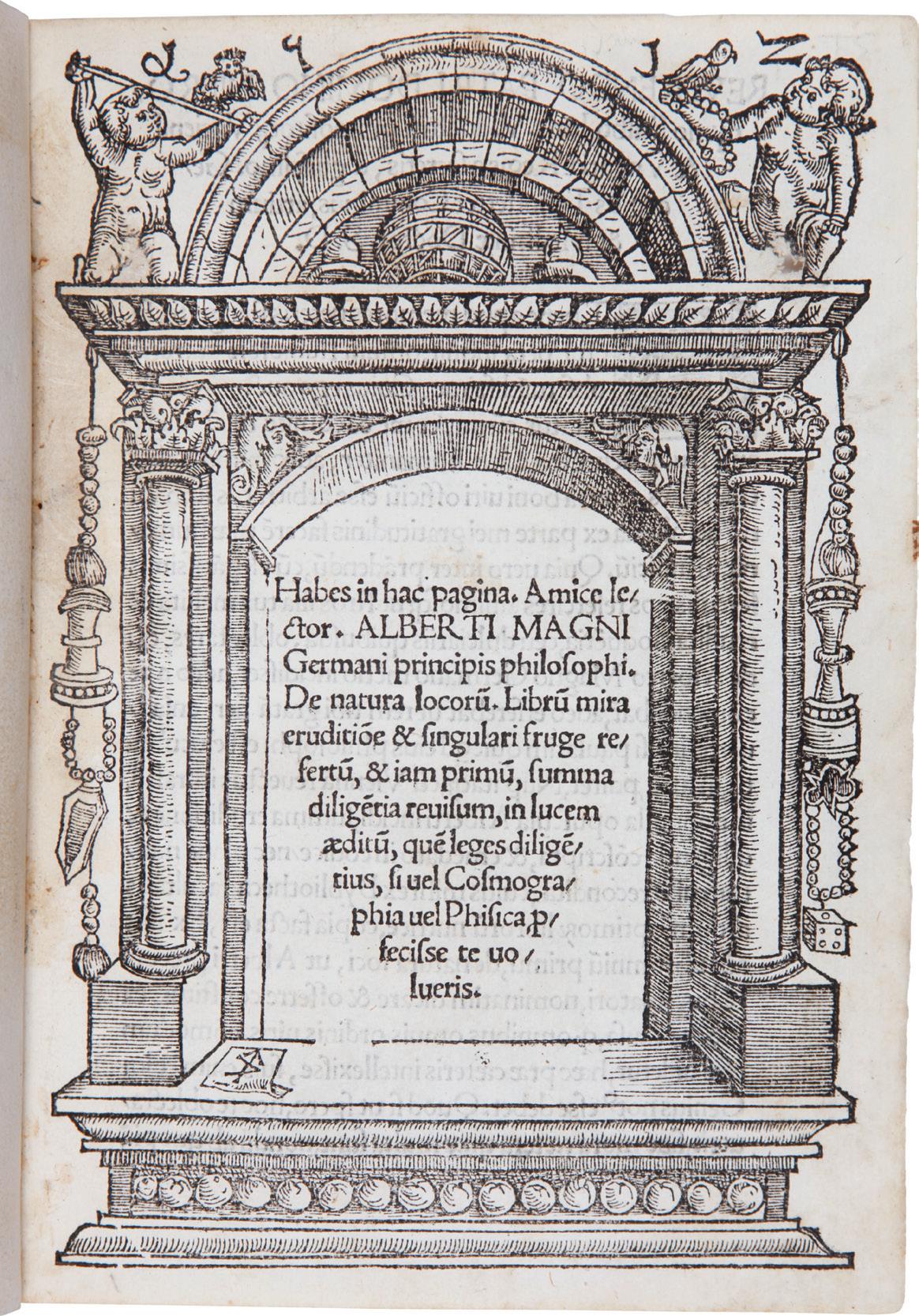

THE PARSONS COLLECTION

THE PARSONS COLLECTION THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA Peter Harrington london IN ASSOCIATION WITH 409 temple street new haven connecticut 06511 (203) 789-8081 amorder@reeseco.com William Reese Company

R. David Parsons (1939-2014)

A dedicated and virtuoso collector, who studied and loved his books

It is an honour and a great pleasure for this group of four specialist dealers from different parts of the world to offer for sale the remaining books of a renowned collector, David Parsons, who passed away unexpectedly in 2014.

Born in Liverpool, England, and an Oxford MA, David moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he practiced as a highly regarded actuary for many years. Approaching retirement age, he found himself entranced with rare books, soon developing into an enthusiastic and knowledgeable collector, and becoming a well-known figure in the rare book world. A board member of the John Carter Brown Library (which awards an endowed fellowship in his name) and the Folger Library, and an active member of the Grolier Club, he was a benefactor and supporter of several libraries, including those of Emory University.

I first met David in the 1990s at the beginning of his book collecting. He often visited the American book fairs, and particularly the big annual California fair, where William Reese Company and Hordern House took adjoining stands and removed the wall between us. Bill Reese and I soon became firm friends with David.

David’s collection quickly became a serious activity. Later, he could say that “Eventually the scope of my collection became defined as the texts of seaborne

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 2

discovery, exploration and settlement from the era of Columbus until that point in the first half of the nineteenth century when little remained to be discovered.”

When David commissioned Anne McCormick and myself at Hordern House to sell his Pacific Voyage collection (the two catalogues of “Rare Pacific Voyage Books from the Collection of David Parsons” appeared in 2005 and 2006) he noted: “This sale will enable me to focus on the other aspect of my collection … the expansion, beginning at the end of the fifteenth century, of the Spanish to the West and the Portuguese to the East and the pre-1492 texts that formed their only knowledge of the areas they into which they ventured.”

That “other aspect” preoccupied David as a collector from then on. Before his premature death in 2014, he added a quite remarkable suite of books to those he already had, to illustrate those two world-defining movements: the earliest Spanish push to the West and the earliest Portuguese push to the East, along with the preColumbian texts that prompted their exploratory and expansionist thinking. For the present catalogue, we have concentrated on David’s collection of voyages and explorations to the West. Arranging the books by order of publication date allows us to see how rich it is in very early material, that is, within 40 years of Columbus’s voyages. It has such a relatively high percentage of titles for those earliest years as noted in European Americana and is especially strong in the conquest of Mexico. Our next selection will focus on voyages and explorations to the East.

Alas, this offering of David’s books is not occurring during his lifetime: he would have enjoyed the process. We are pleased to have received the blessing of his widow, Mary Parsons, as the appropriate buyers of David’s books. Bill, too, is no longer with us, but his name and spirit live on in the William Reese Company, the dealership he founded in New Haven, Connecticut, now under the ownership of Peter Harrington and James Cummins, and managed by Nick Aretakis.

We hope our catalogues prove suitable memorials for the fine man and brilliant collector that was David Parsons. I know I can speak for my partners in saying that we thank Mary and her family for entrusting us with this responsibility.

Derek McDonnell Hordern House, Sydney

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 3

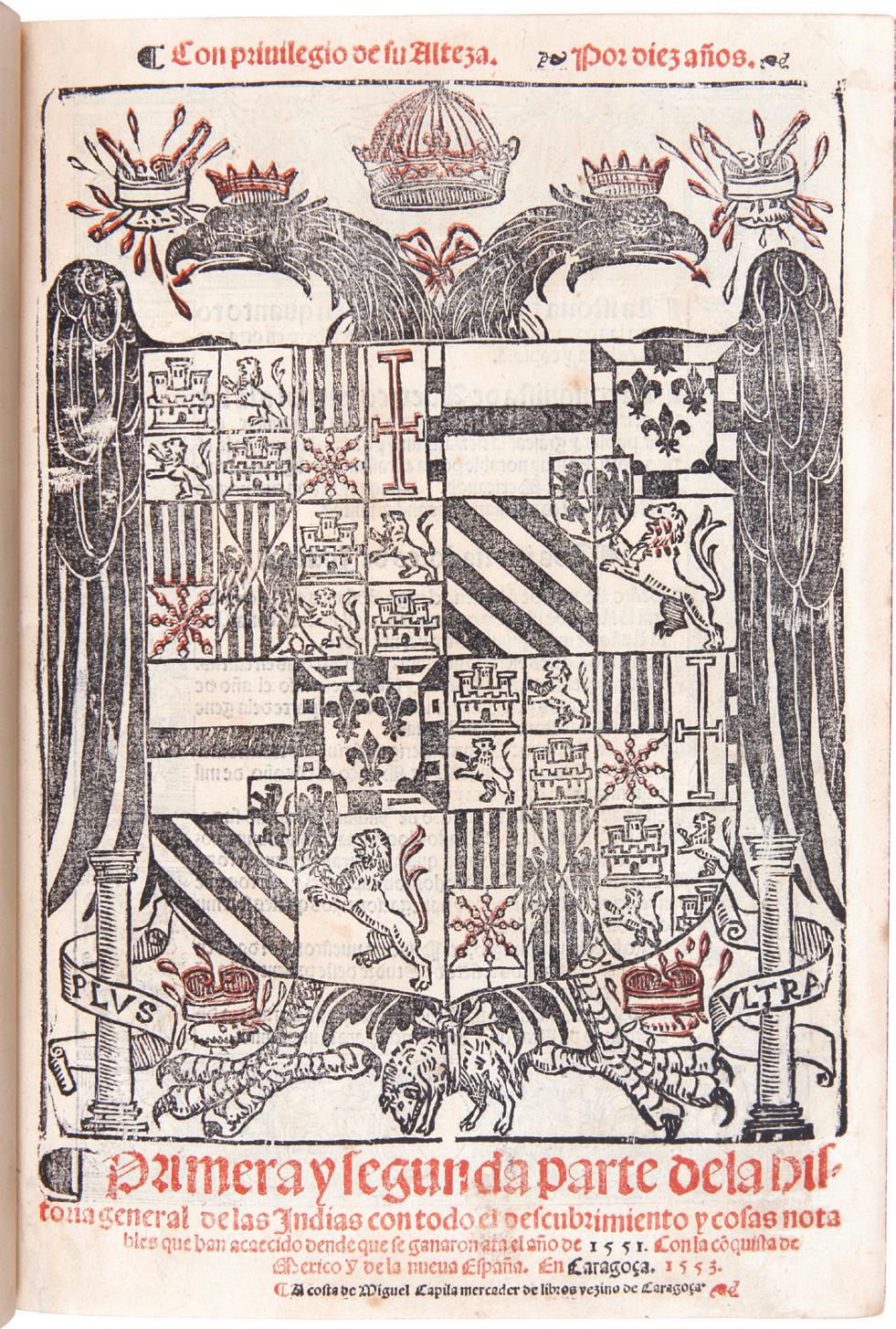

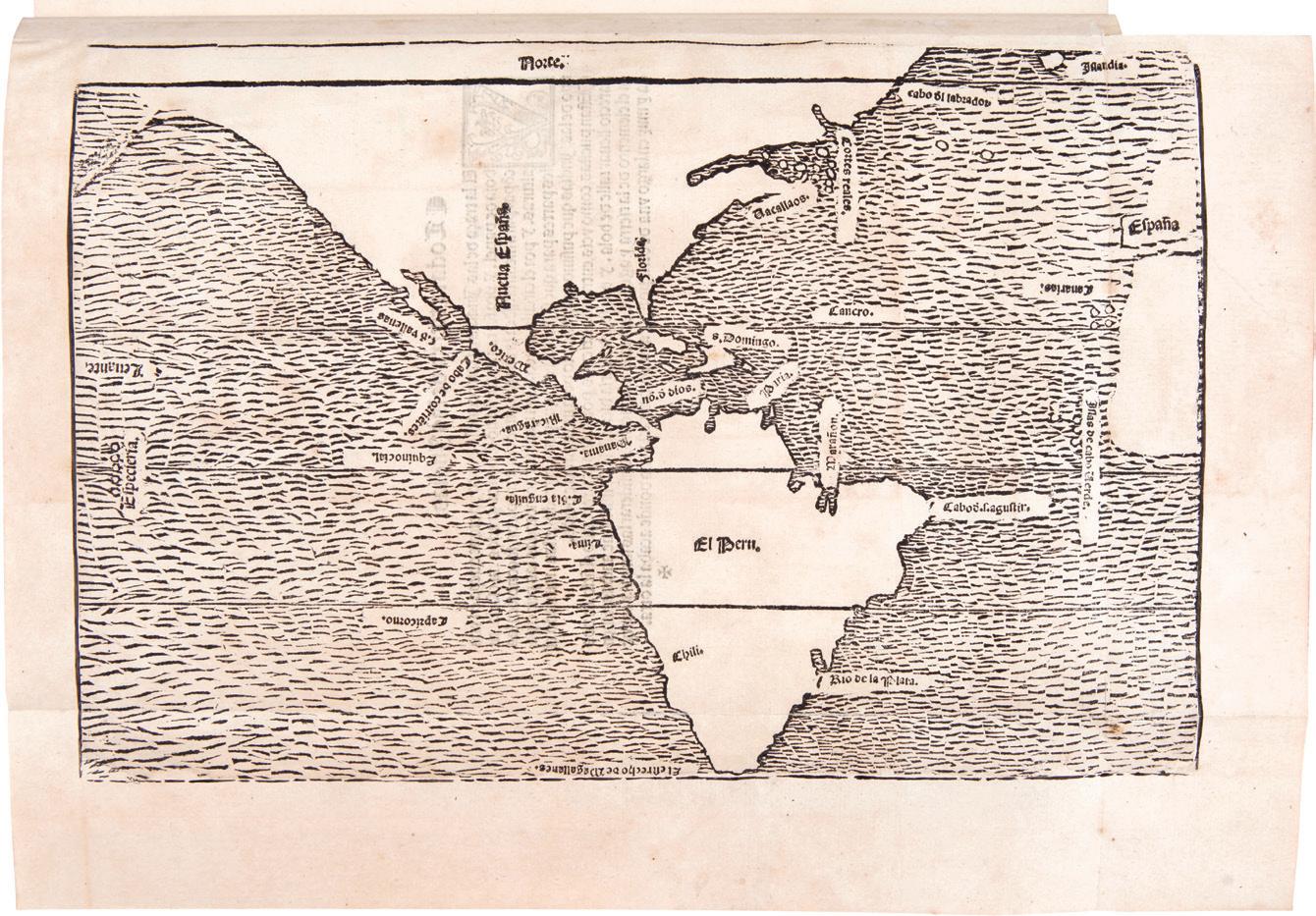

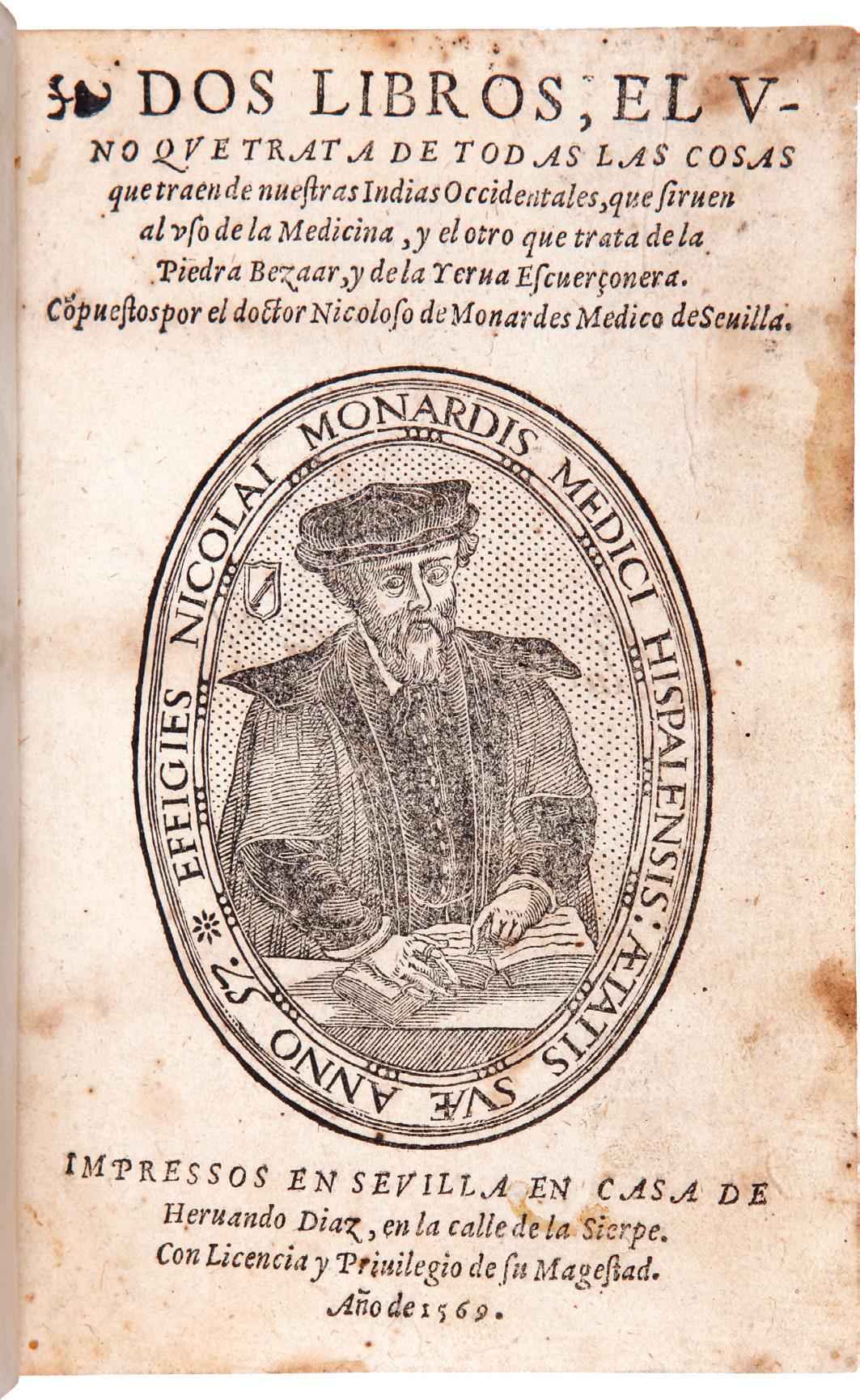

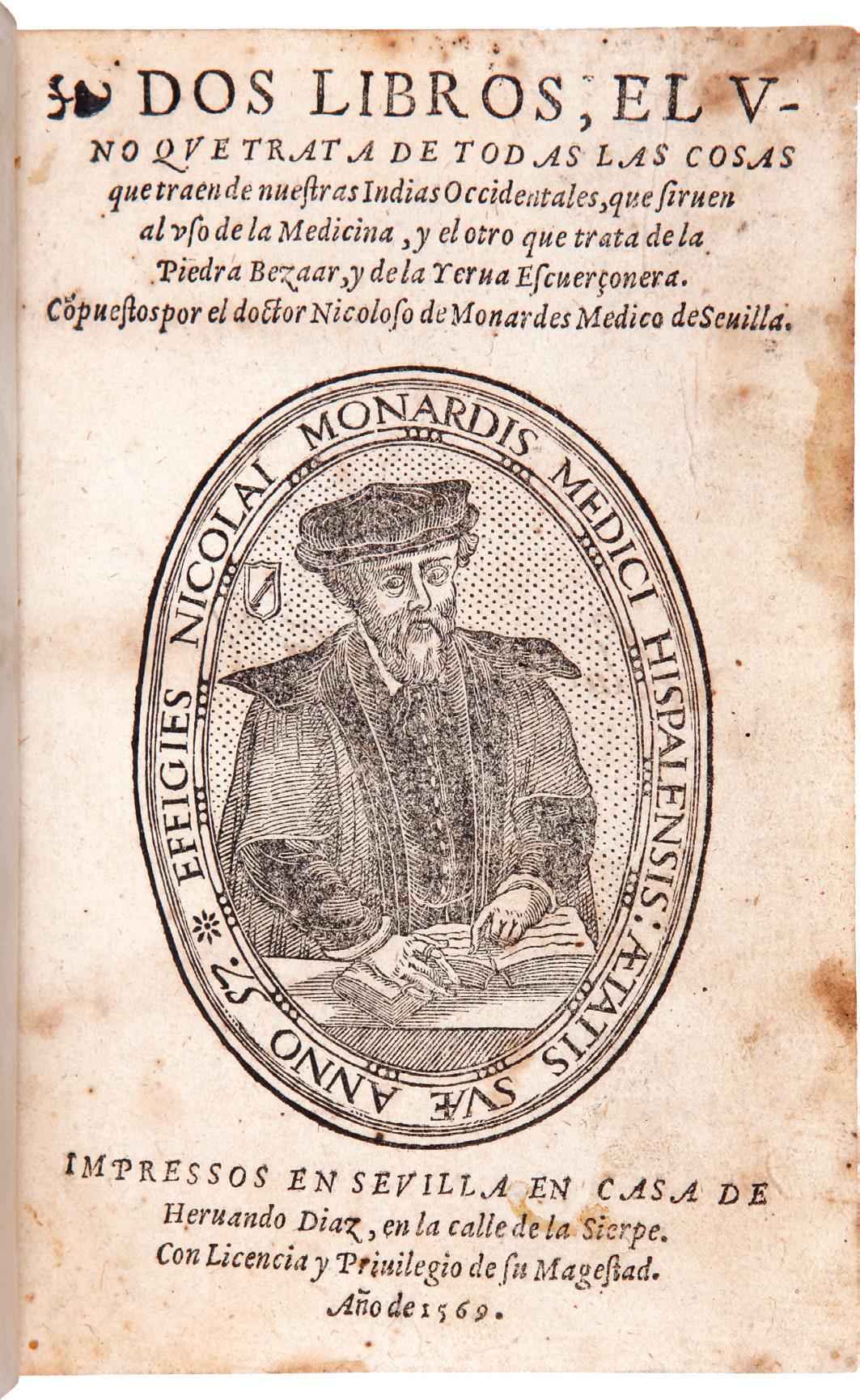

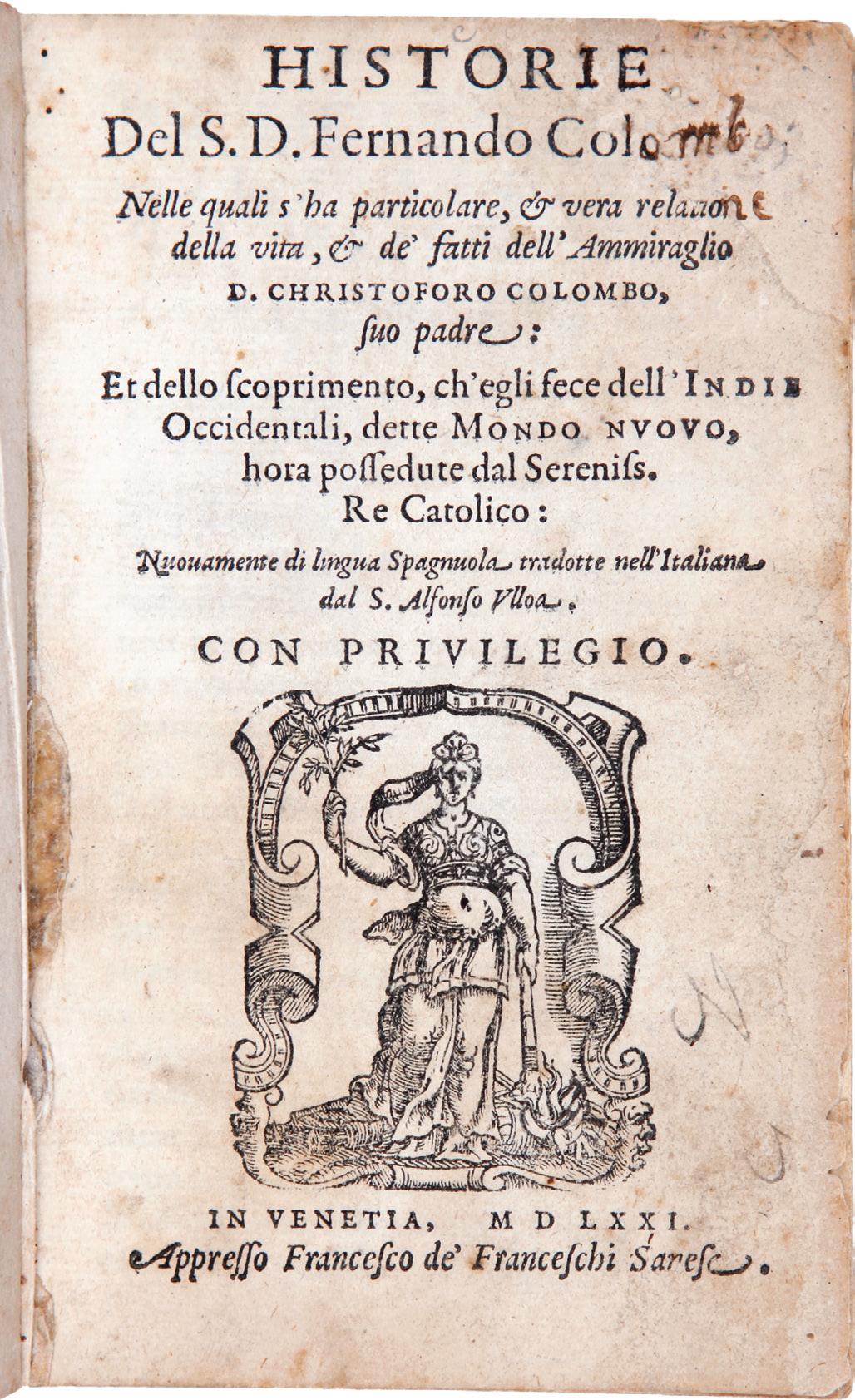

4 author index Albertini, Francesco 9 Albertus Magnus 12 Anghiera, Pietro Martire d' 16, 25, 26, 29, 34 Angliara, Juan de 23 Apianus, Petrus 24, 32 Barros, Joao de 41 Carvajal, Bernardinus 2 Cataneo, Giovanni Maria 14 Columbus, Christopher 40, 53 Columbus, Fernando 49 Cortes, Hernan 21, 25, 26 Diaz, Fr. Juan 22 Enciso, Martin Fernandez de 19 Eusebius Caesarensis 17 Fracanzano da Montalboddo 7 Geraldini, Alexri 52 Glareanus, Henricus 28 Glogoviensis, Joannes 6 Gomara, Francisco Lopez de 47 Grunpeck de Burckhausenn, Joseph 4 Grynaeus, Simon 38 Hutten, Ulrich von 20 Huttich, Johann 33, 38 Las Casas, Bartolomeo de 42–46 Leonardus, Camillus 3 Lopez de Gomara, Francisco 47 Marineo Siculo, Lucio 31 Martyr, Peter: see Angheira Maximilianus Transylvanus 27, 37 Mela, Pomponius 1 Monardes, Nicolo 48 Montalboddo, Fracanzano da 7 Multivallis, Johannes 17 Nodal, Bartolome Garcia de 51 Olave, Antonio de 30 Oviedo y Valdes, Gonzalo Hernez de 34, 35 Pigafetta, Francisco Antonio 37 Ptolemaeus, Claudius 11, 13, 50 Ramusio, Giovanni Battista 34, 39 Regiomontanus, Johannes 15 SchÖner, Johann 15 Solinus, Caius Julius 24 Stobnicy, Jan de 10 Stobnicza, Johannes de 10 Vespucci, Amerigo 5 Waldseemuller, Martin 8 Werner, Johannes 13 Xerez, Francisco de 36 Zumarraga, Juan de Martin de Valencia 30

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

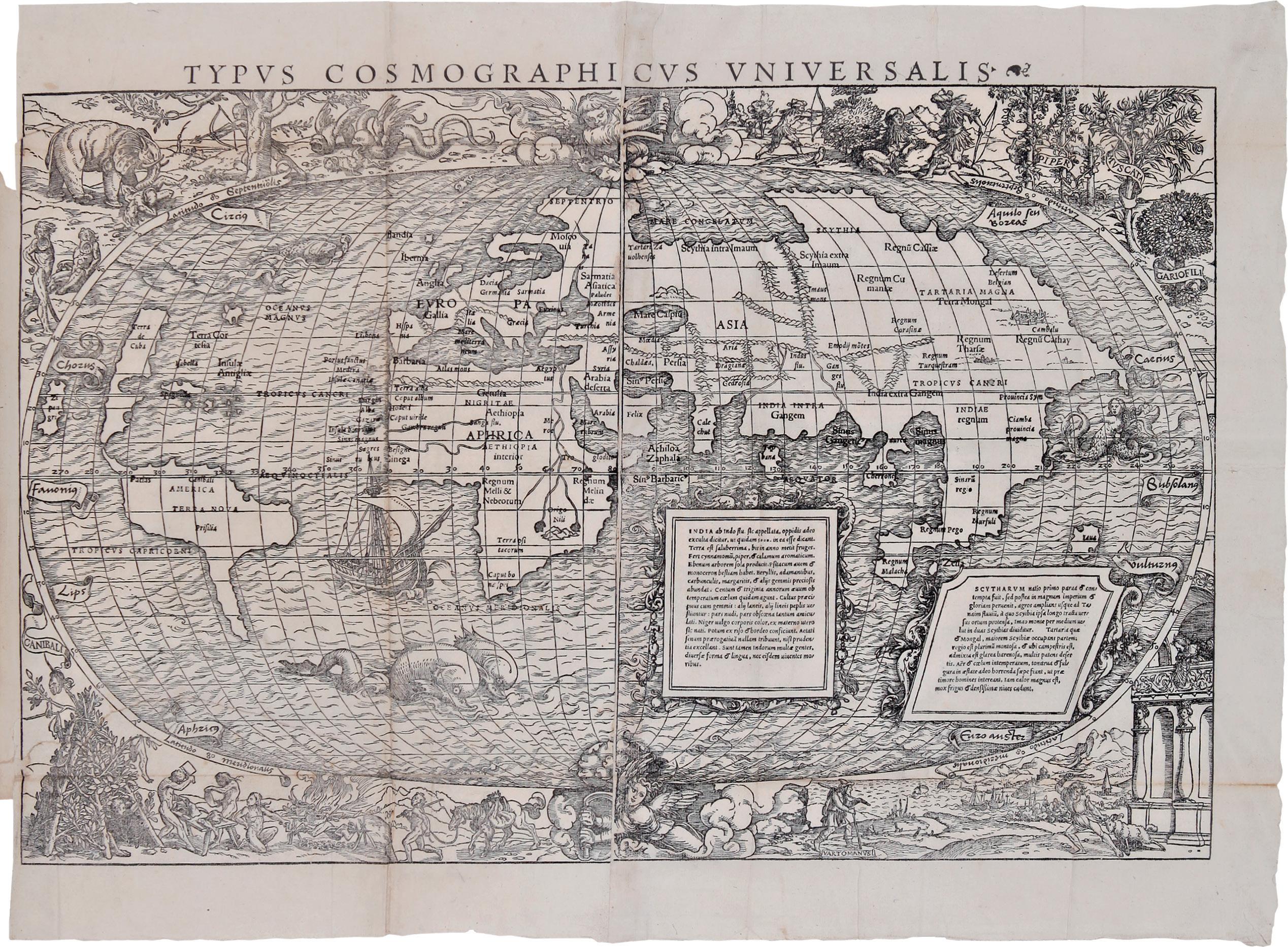

THE KNOWN WORLD ON THE EVE OF THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

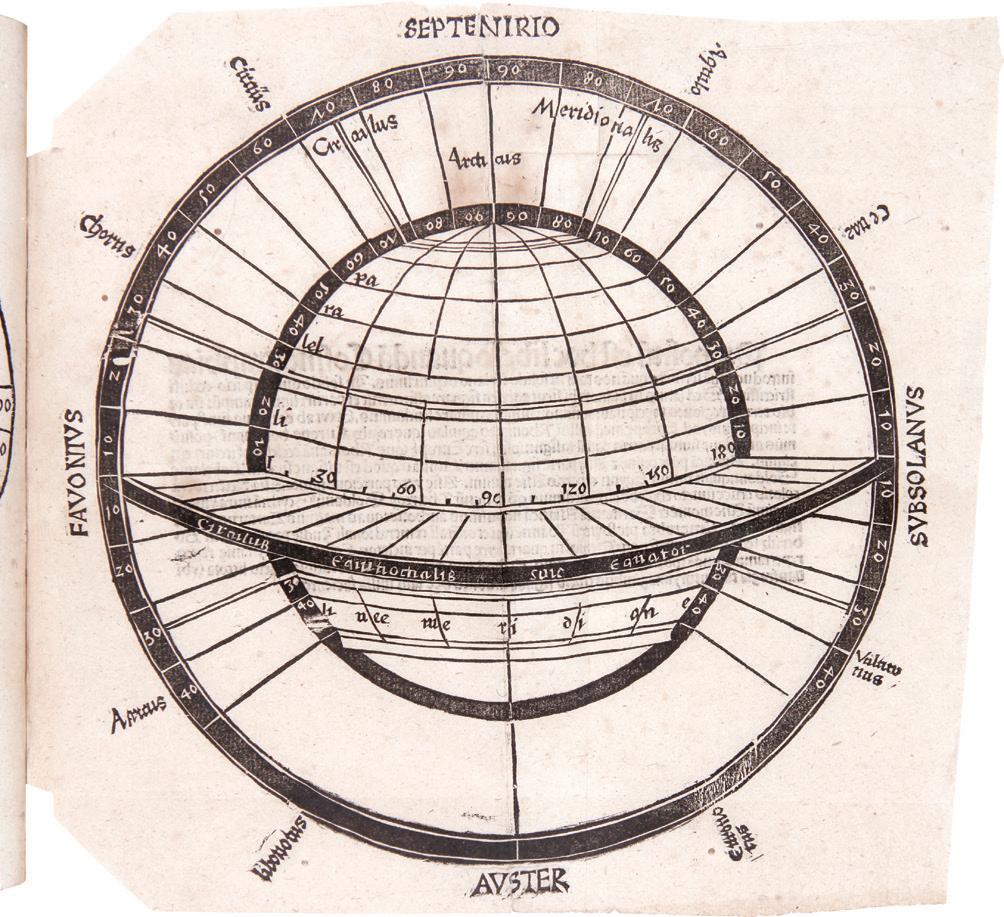

1. MELA, Pomponius. Cosmographia, sive De situ orbis. Add: Dionysius Periegetes: De situ orbis. Tr: Priscianus. Venice: Erhard Ratdolt, 18 July 1482.

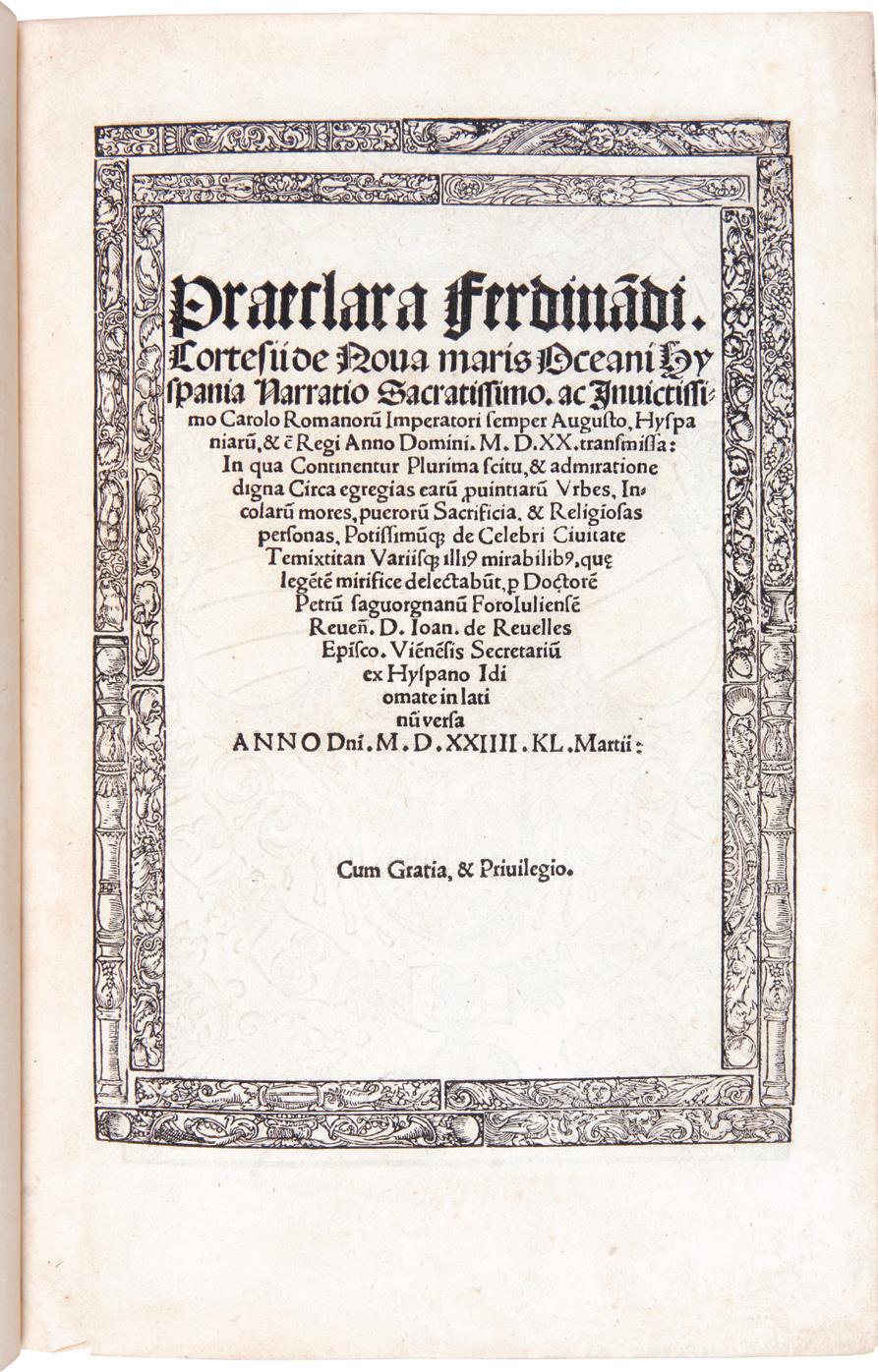

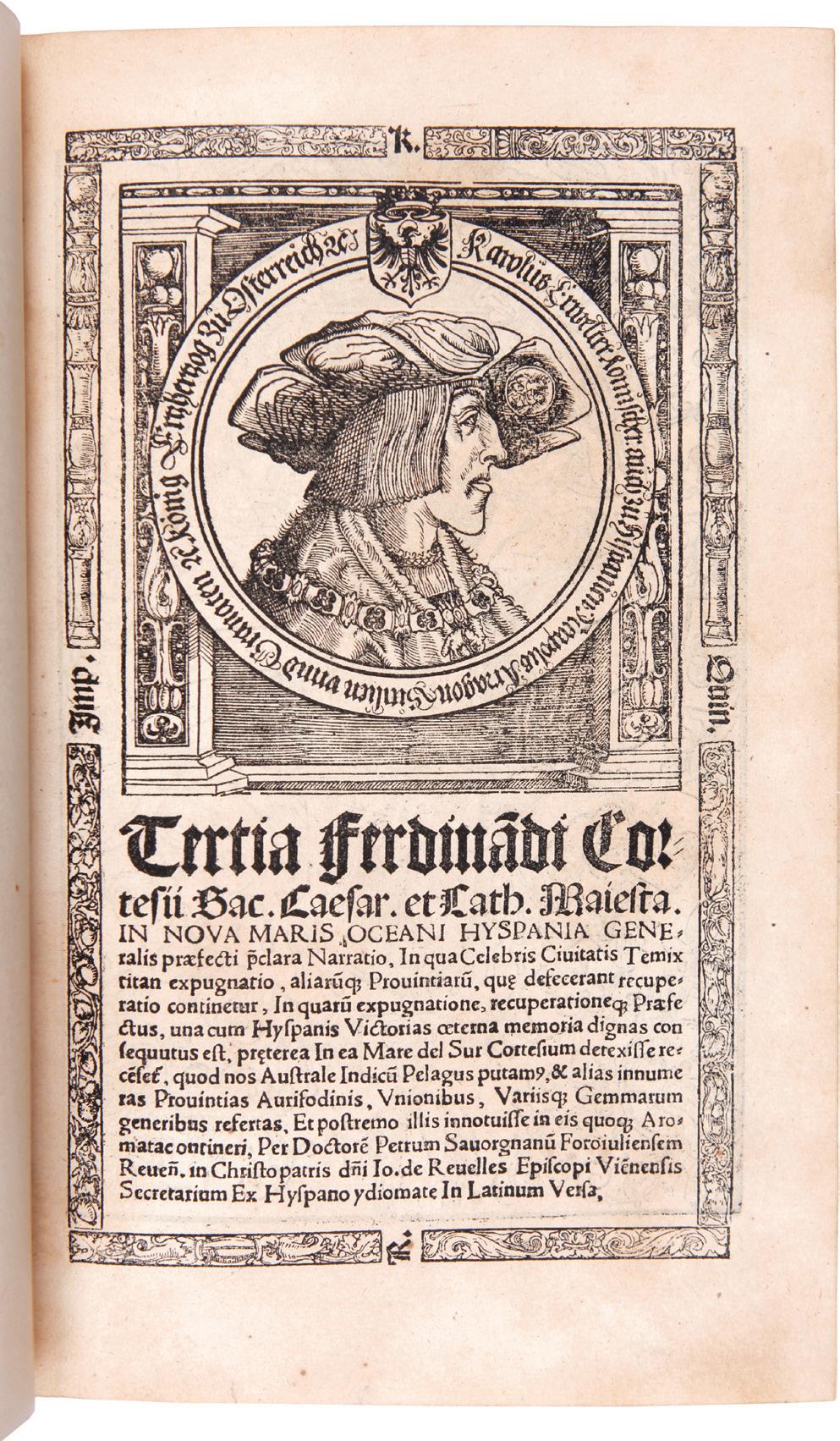

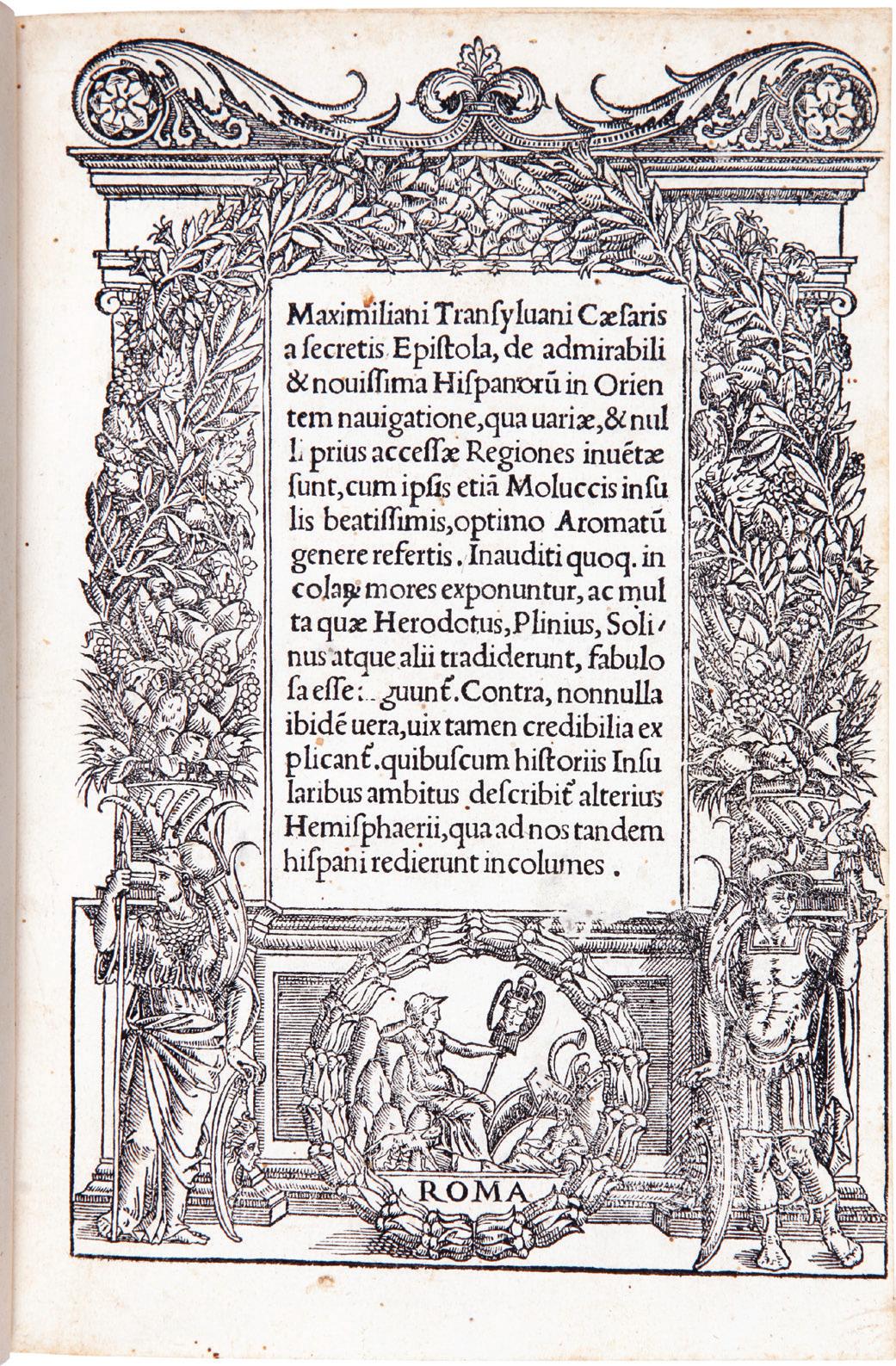

Chancery quarto (191 × 145 mm): A–F 8; [48] leaves. Full-page woodcut map with type inserts on A1 verso, with the oceans hand-colored at an early date. Woodcut white-on-black initials. A few early marginal annotations in red. Late eighteenth-century Italian green morocco gilt, red morocco spine label, gilt turn-ins, all edges gilt. Boards a bit rubbed. Endpapers renewed, first leaf possibly supplied from another copy, fore-margin of A2 restored, a few small wormholes, stamp removed from verso of the map.

Two of the most important collectors of Americana, E. D. Church and Thomas W. Streeter, both began the catalogues of their collections with this title. The choice could not be more apt. No other printed work provides a resume of ancient geography and registers the kind of geographical advance that would result from the voyages of Columbus and Vespucci. “The revival during the Renaissance of geographical study resulted in the first printings of the ancient works of Mela (1471) and Ptolemy (1475) which greatly stimulated exploration. Mela’s concept of the world as published here—ten years before the discovery of the New World—was the most widely accepted cosmography in Europe; his ideas were being proved out by the Portuguese explorations around Africa” (Streeter).

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 6

A scarce incunable edition of the most widely accepted cosmography in Europe ten years before the discovery of the New World, Mela’s Cosmographia contains the first and only map published in the incunable era to reflect voyages that took place during the age of exploration. The map is just the second woodcut map to be published in Italy (preceded by the T-O map in Ratdolt’s 1480 edition of Rolewinck), and one of the earliest maps to appear in any geographical book, as opposed to an atlas. The 1482 edition of Mela was the first edition of that work to include a world map.

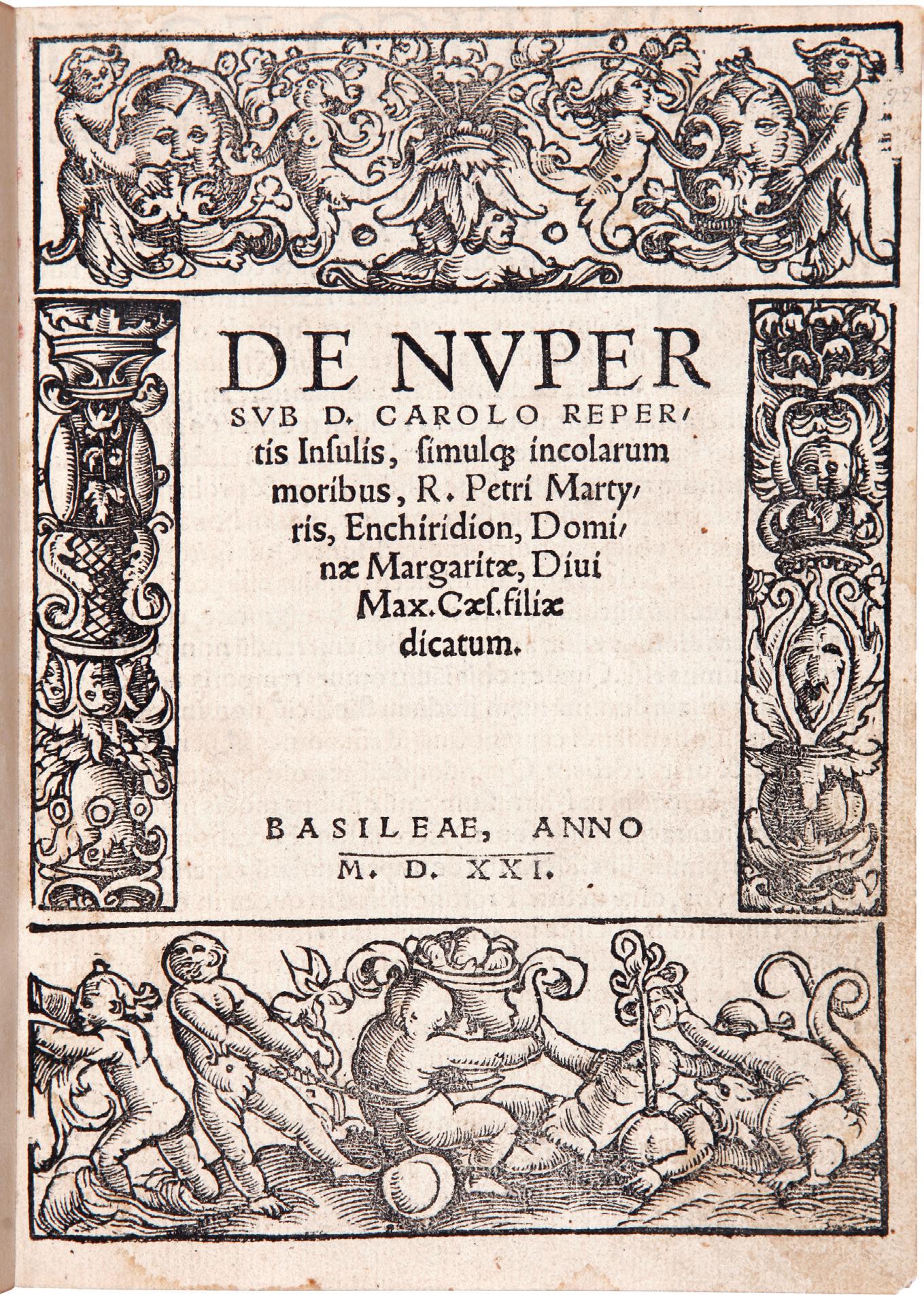

In 1415, Portugal conquered Ceuta, establishing the first European foothold in Africa and marking the beginning of European overseas expansion. Under Prince Henry the Navigator, Portugal continued pushing southward along the African coast. The 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas gave the Guinea coast, the Azores, the Madeiras, and Cape Verde Islands to Portugal, and the Canaries to Castille. The present map modifies the Ptolemaic rendering of western Africa to cut into the east, revealing a true Western Africa based on reports of Portugal’s success further south, and making it current with known geographical knowledge.

“The map of the known world . . . is drawn on the conical projection and is based for the most part on w. An important improvement, however, lies in its clear recognition of the south-eastward trend of the west African coast below the 12 degree parallel. These accord with Portuguese discoveries up to the year 1447 and the gradual unfolding of the Gulf of Guinea in light of the information brought back by subsequent expeditions in the period 1460–71. No earlier printed map recognized this important step towards the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and no map in the incunable editions of Ptolemy reflected this knowledge” (Campbell). The maker of the map is unknown but is often credited to the printer Ratdolt. The editio princeps of the work appeared in 1471 without a map, as did the four subsequent editions which followed. The map was copied for a Salamanca edition of 1498 and for Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

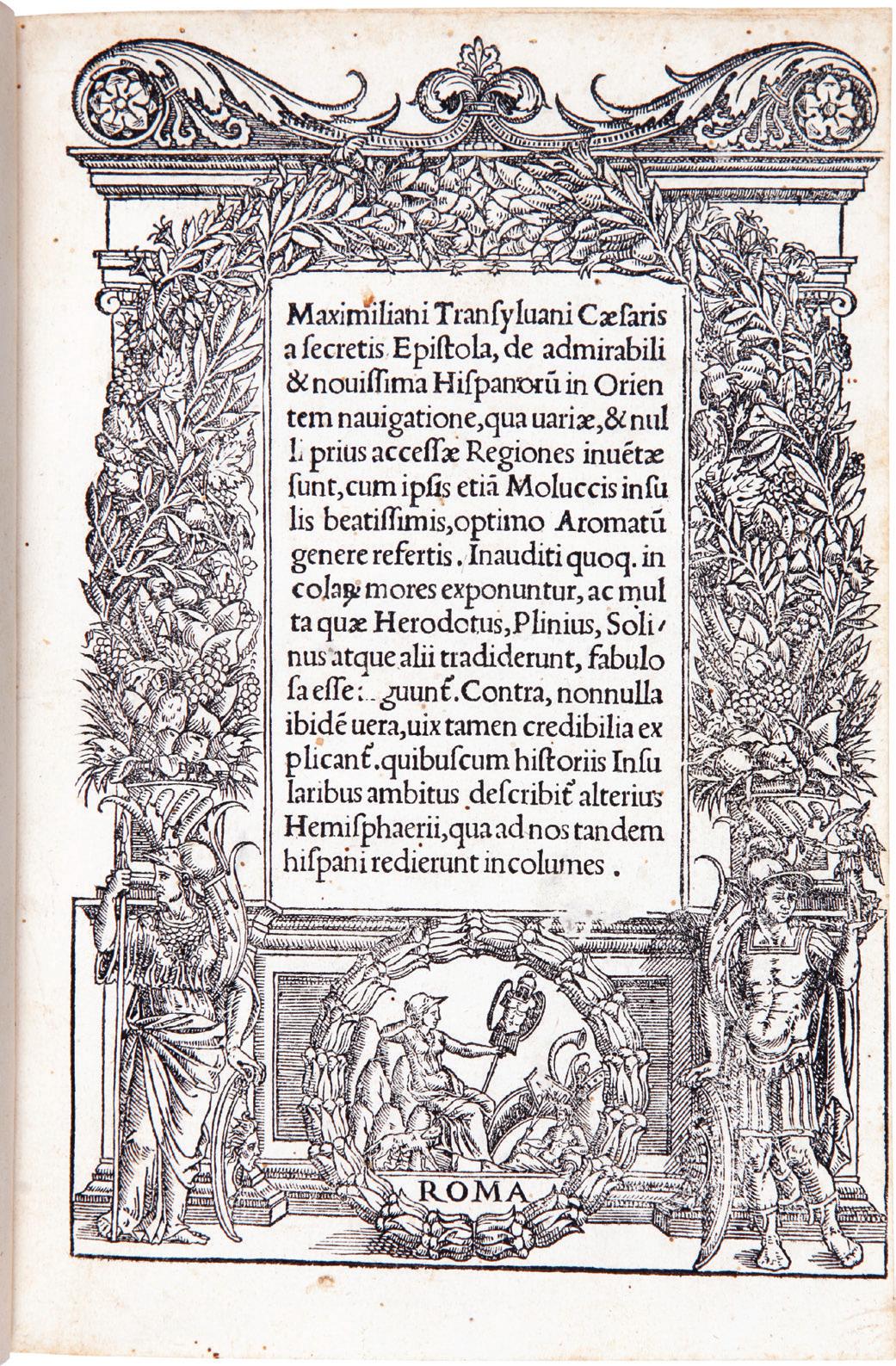

The only Latin geographical treatise to survive from antiquity, this work would certainly have been among those studied by Columbus. Although many of the theories of the first-century Roman geographer would have been irrelevant to the planning and execution of his First Voyage, one can imagine his thoughts reading Mela’s theory on the probability that the unexplored southern hemisphere was inhabited while he prepared to sail west, headed for what would become known as the New World.

BMC V 286; Bod-inc M-179; BSB-Ink P-687; Campbell, Earliest Maps 91; Church 1; Goff M452; GW M34876; HC 11019*; ISTC im00452000; Klebs 675.6; Oates 1751; Proctor 4385; Rhodes (Oxford Colleges) 1191; Shirley, Mapping of the World 8; Streeter Sale 1; Walsh 1809, S-1809.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 7

SOLD

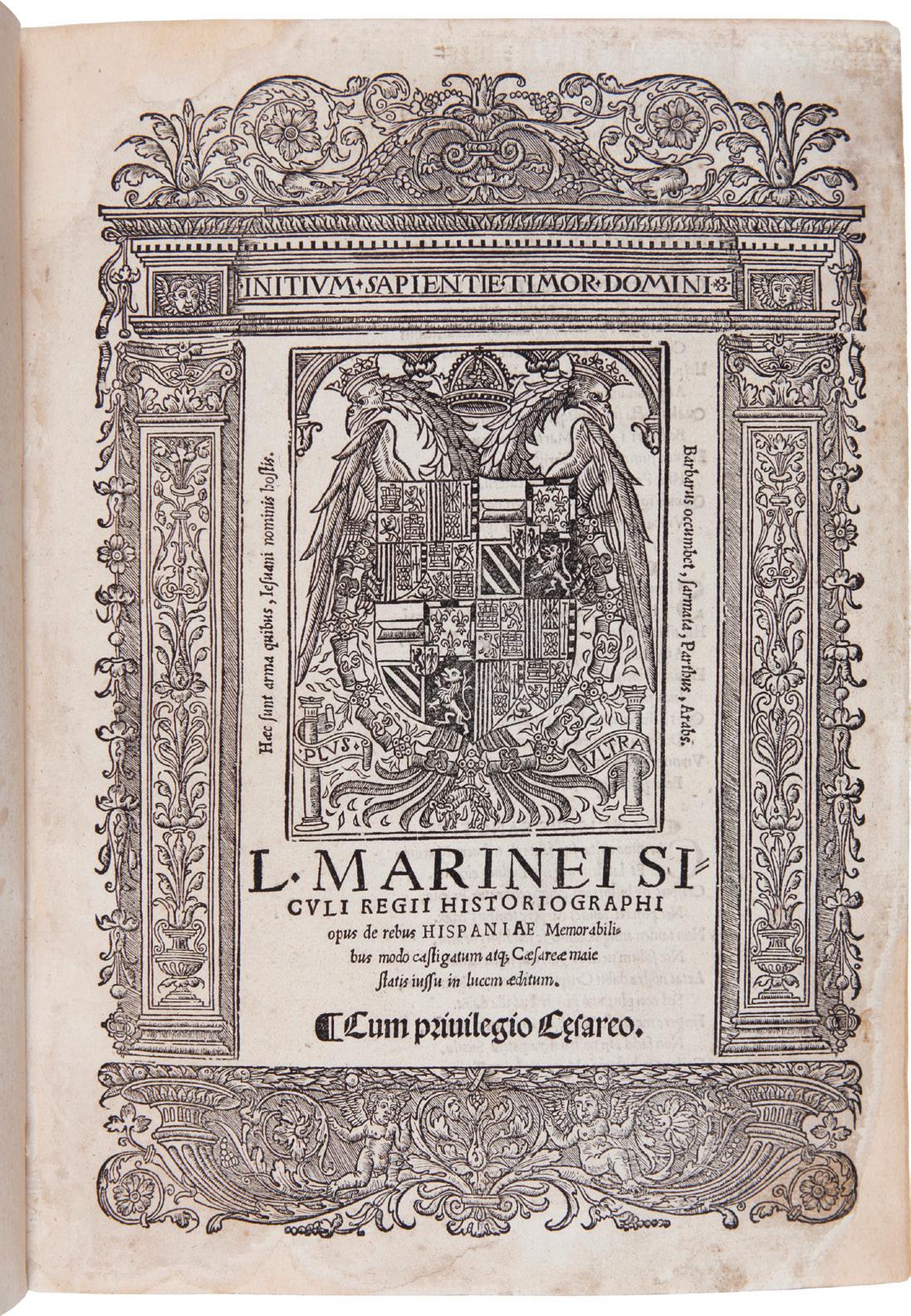

ONE OF THE EARLIEST MENTIONS OF THE DISCOVERY

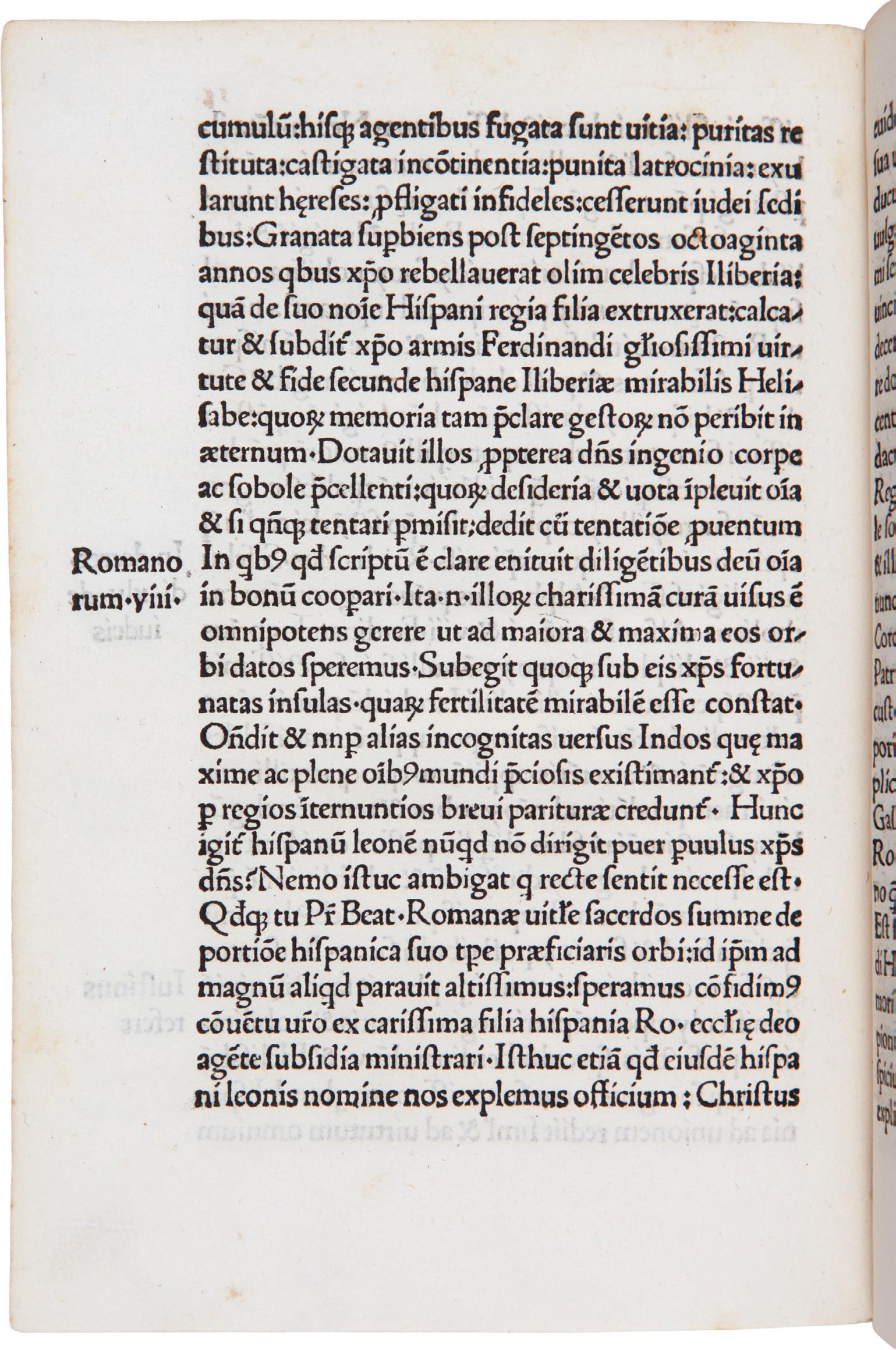

2. CARVAJAL, Bernardinus. Oratio super praestanda solenni obedientia Sanctissimo D.N. Alexandro Papae VI ex parte Christianissimorum dominor Fernandi & Helisabe Regis & Regina Hispaniae. [Rome: Stephan Plannck, ca. 19 June 1493.]

Quarto (195 × 135 mm): a 8; [8] leaves. A few manuscript chapter headings in an early hand, and some underlining. Early twentieth-century dark gross-grained morocco by Sangorski & Sutcliffe, gilt-ruled, spine gilt with raised bands. Minor staining in outer margin, but generally a fresh, unwashed copy. Very good. Provenance: Helmut N. Friedlaender (booklabel; his sale, Christie’s NY, April 23, 2001, lot 37).

Exceedingly scarce first and only edition of one of the earliest printed documents to mention the discovery of the New World—a mere four months after Columbus’s return from his first voyage. The work is a lynchpin in the geopolitical contest between Spain and Portugal over the division of the newly discovered lands, and

Carvajal is recognized for influencing Pope Alexander VI’s strategy of legitimizing European colonization of the Americas through the conversion of its indigenous population to Christianity. Delivered on June 19, 1493, his oration was a critical affirmation of the papal bulls issued the previous month in which Alexander granted Spain possession of not only the islands discovered by Columbus, but also of any further territories that would yet be discovered.

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 8

When Columbus returned from his first voyage in March 1493, the Portuguese King John II immediately claimed the newly discovered islands for himself, citing the Treaty of Alcáçovas of 1479 and the bulls of Pope Sixtus IV. From Barcelona, the Spanish monarchs sent an urgent dispatch to Rome—via Carvajal, their permanent ambassador to the Holy See—to secure their own claims on the new territories. After private meetings with Carvajal, the pope issued a sequence of three bulls on May 4 and 5, 1493, in which he not only conferred the rights to Columbus’s discoveries on the Spanish crown, but for the first time drew a meridian line demarcating a part of the world in which any non-Christian lands were given over to Spain. For Portugal, the papal ruling was a severe blow, and their protests eventually led to a compromise in the Treaty of Tordesillas (June 7, 1494), in which the north–south line was moved further west and their own claims on any undiscovered lands east of it upheld. At the time Carvajal presented the present oration, however, Spain was at a clear advantage. In his oration of obedience, Carvajal underlines the Borgia pope’s Spanish origins (Borja) and extols the piety and virtue of Spain under the Catholic kings. Arguing that God has created this alliance of a Spanish pope and Spanish monarchs for the purpose of furthering the faith, he then introduces Columbus’s discoveries.

Carvajal’s oration galvanized theological debate in Rome and inspired Pope Alexander, who had ascended to the papacy the very year of the Discovery, to throw his weight behind the missionary conquest of the New World. Carvajal’s theological argument influenced Alexander’s policy on territorial concessions directly: where the Portuguese might have hoped for him to arbitrate merely in their dispute with the Spanish, Alexander, following Carvajal’s reasoning, considered all earthly dominion as property of the pope, and therefore his to give in free donation to whom he saw fit.

The sequence of “first mentions” of the Discovery is a complicated and perhaps fruitless task. Many of the earliest candidates lack printed dates or “true” printed dates. For example, while the first issue of the Plannck translation of the Columbus Letter contains a date, generally interpreted to be April 25, 1493, subsequent editions merely repeat this date. Of the earliest items mentioning the Discovery listed by Harrisse following the 1493 editions of the Columbus Letter, #8 is a brief poem by Giuliano Dati dated October 25 and thought to be published in Florence; #9 is a supplement to Dati’s poem, expressly signed from Florence and dated the following day; #10 a Spanish-language miscellany published in Seville by Ortiz, giving the year but no month; and the present work, the date of whose public delivery (June 19) is known from the title, but not the date of printing. For items of this kind, the chronology between public oration and printed text cannot always be precisely known. The oration may have been printed prior to delivery, so that a select audience could follow the text, or printed shortly afterwards, though given the stakes at issue in the present instance, probably not much later. It would seem very likely, however, especially given the Rome imprint by the same printer as the Columbus letter, that the present work in fact preceded several of the others listed by Harrisse.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 9

continues overleaf

Goff lists ten copies in the United States: Chapin Library, Cornell, Huntington, Hispanic Society of America, Lilly, JCB, LC, NYPL, Free Library of Philadelphia, and Princeton (Kane). ISTC adds no new American copies, locates nineteen copies at sixteen locations worldwide: BL, BNF (2), Chantilly, Koblenz, Mainz, Munich, Wolffenbüttel, Cremona, Milan, Trivulziana (2), Naples, Perugia, Rome BN, BAV (2), Madrid BN, St. Petersburg, Wroclaw. The work is much scarcer on the market, with only the present copy having come up twice at auction in the past half century.

BSB-Ink C-163; Church 3; European Americana 493/2; Goff C221; GW 6145; IGI 2532; Harrisse (BAV) 11; Medina (BHA) 11; Sabin 11175. On Carvajal see Vicente Calvo Fernández “El cardenal Bernardino de Carvajal y la traducción latina del ‘Itinerario’ de Ludovico Vartema,” Cuadernos de filología clásica: Estudios latinos, 18 (2000), 303–22; José Goñi Gaztambide, “Bernardino López de Carvajal y las bulas alejandrinas,” Anuario de historia de la Iglesia, 1 (1992), 93–112.

SOLD

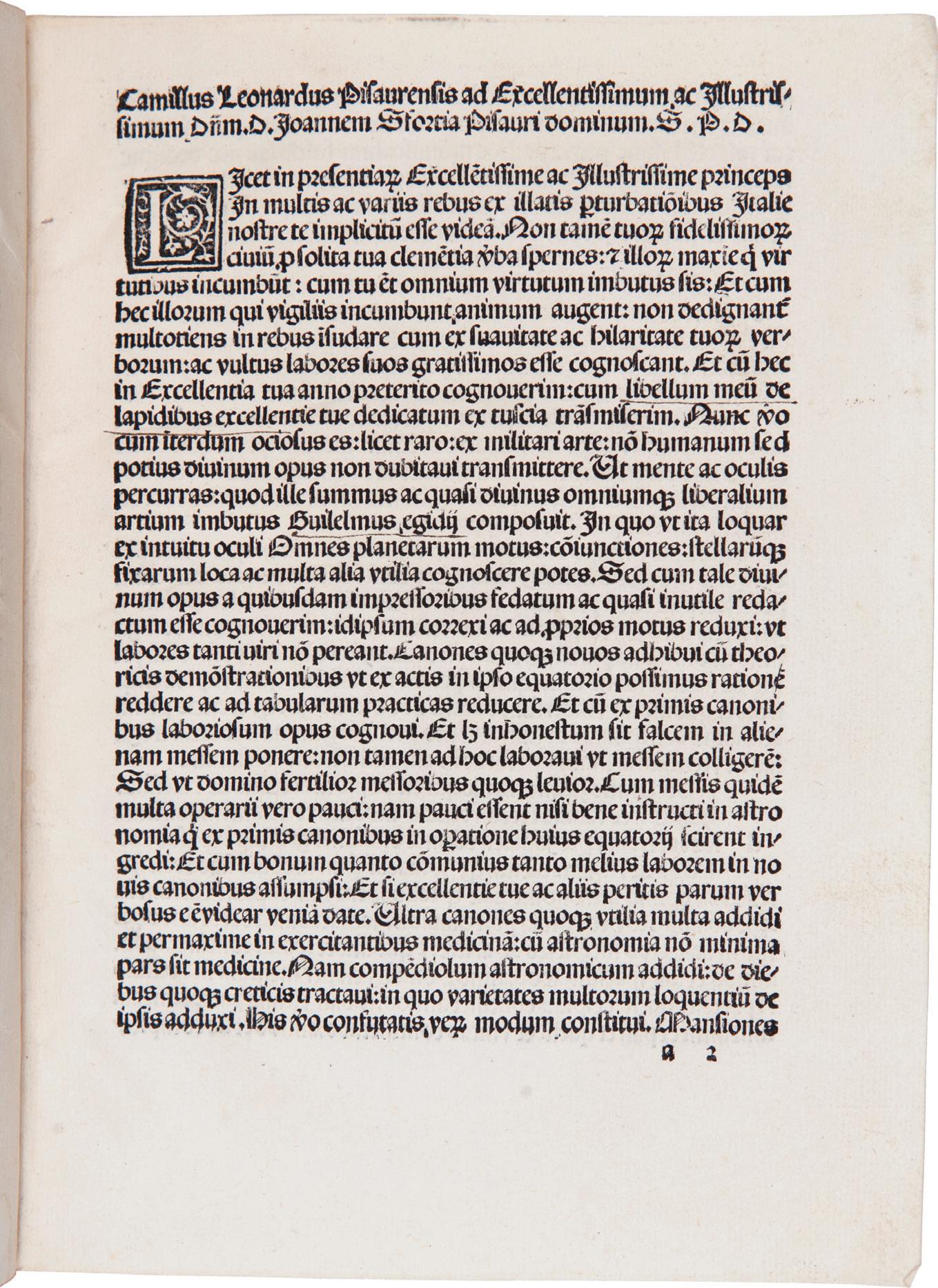

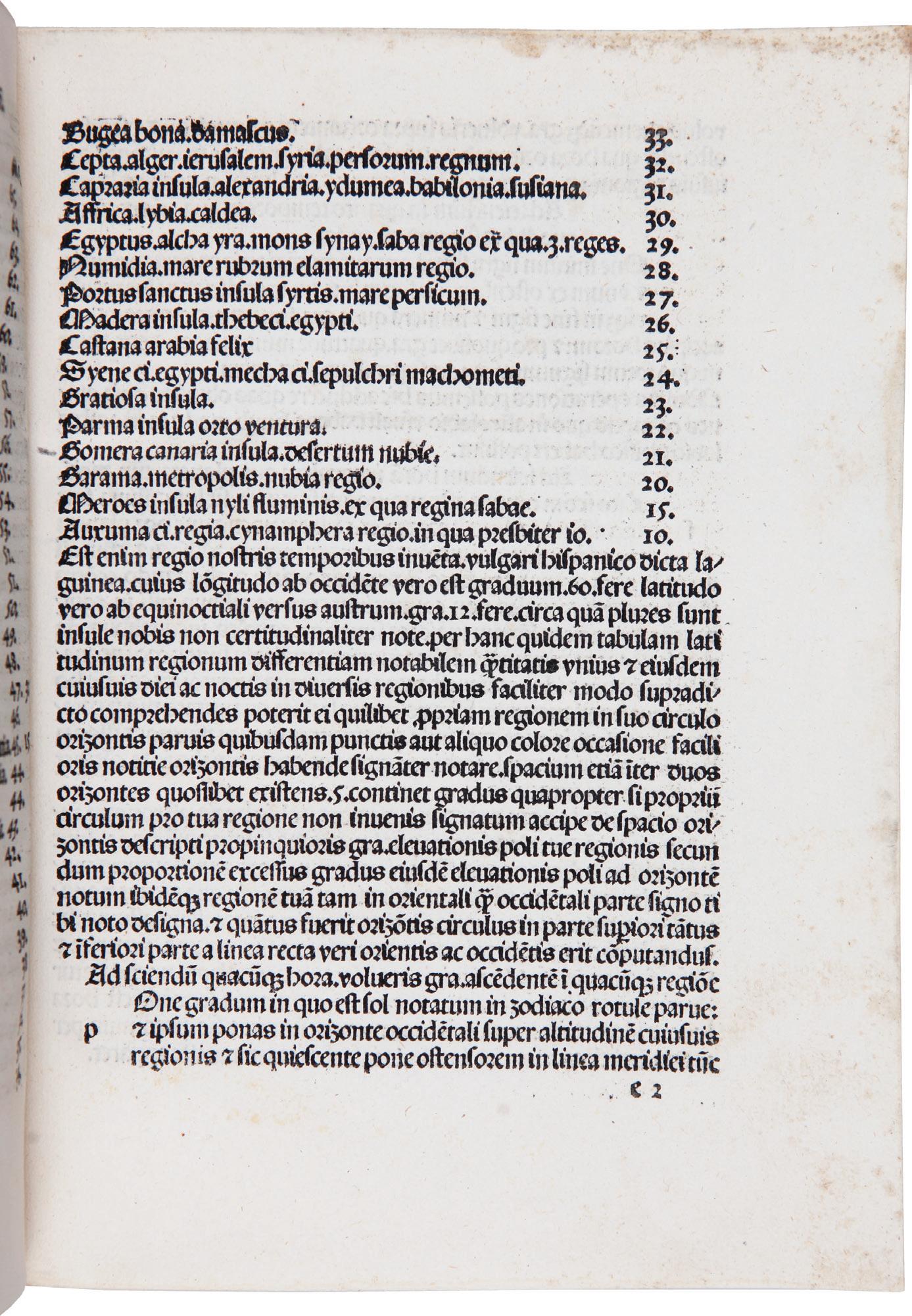

THE FIRST OBTAINABLE BOOK ON THE EQUATORY: A LITTLE KNOWN AMERICANUM

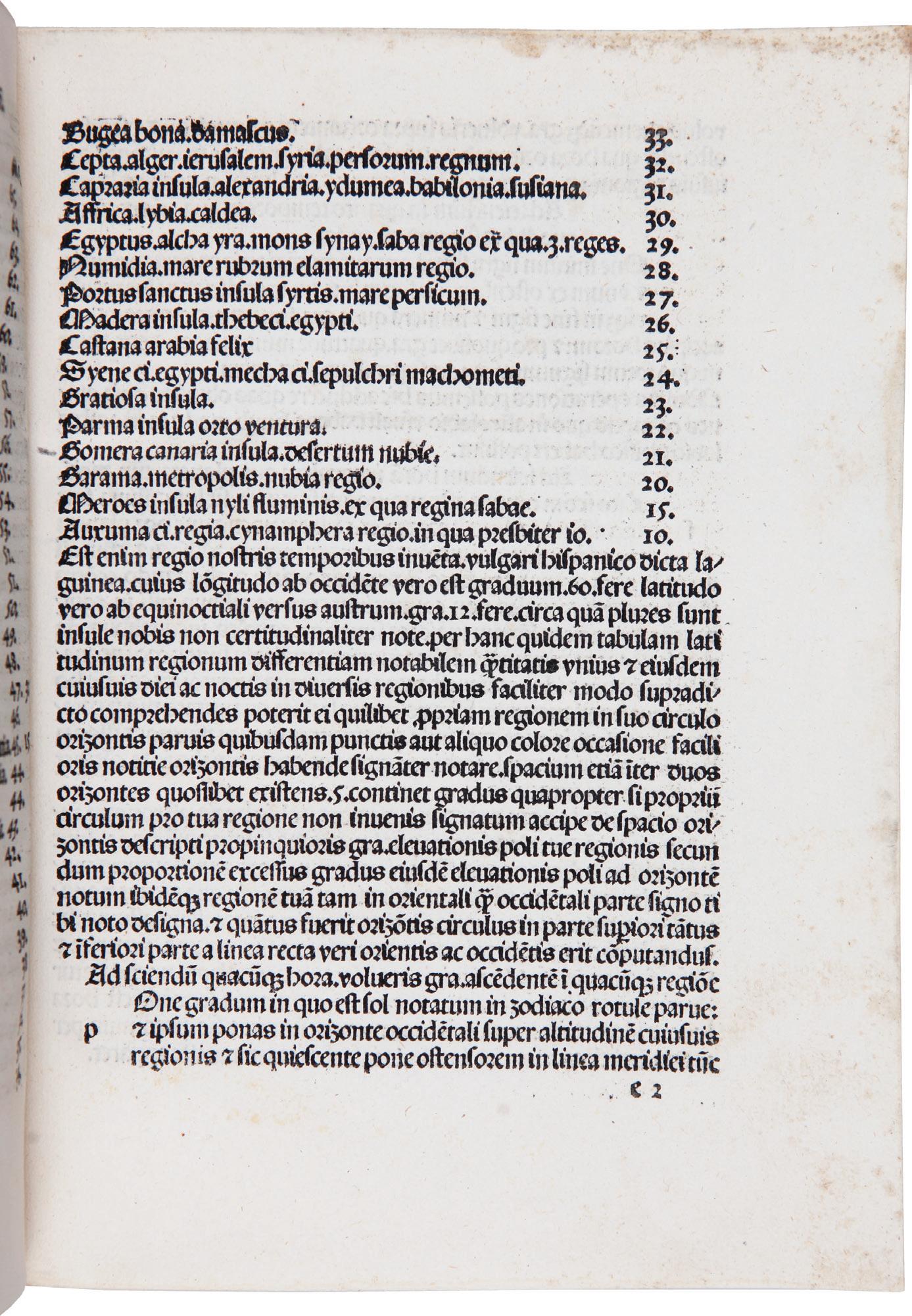

A little known and very early Americanum, the work’s American interest was first described by the bookseller E. P. Goldschmidt in his famous article “Not in Harrisse”, in which he quotes a passage from sig. e2 of the present work, supplying the following translation and interpretation: “‘There exists also a region discovered in our lifetime, called in Spanish “la Guinea”, whose longitude is about 60 degrees west (viz. from Alexandria) and the latitude about 12 degrees south of the equator; nor far from there are several islands of which nothing is known with certainty.’ It is not unlikely that this passage refers to the discoveries of Columbus as yet still unconfirmed by Vespucci’s voyages. It is clear that it does not refer to the Canary Islands, whose exact position (Gratiosa, Orto Ventura, Canaria insula) is given

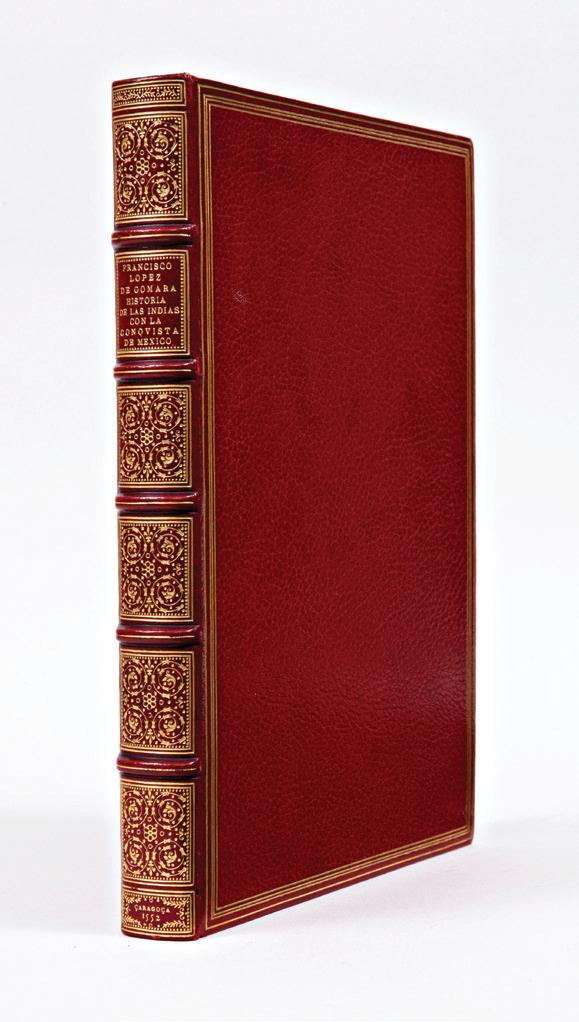

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 10

a few lines above it. The indication ‘somewhere near the Gold Coast’ may seem strange to us now, but in 1496 this corresponds to the generally current notions based on the fact that it was from the west coast of Africa that Columbus started westwards along the equator until he struck Hispaniola” (“Not in Harrisse,” in Essays Honoring Lawrence Wroth [1951], p. 132).

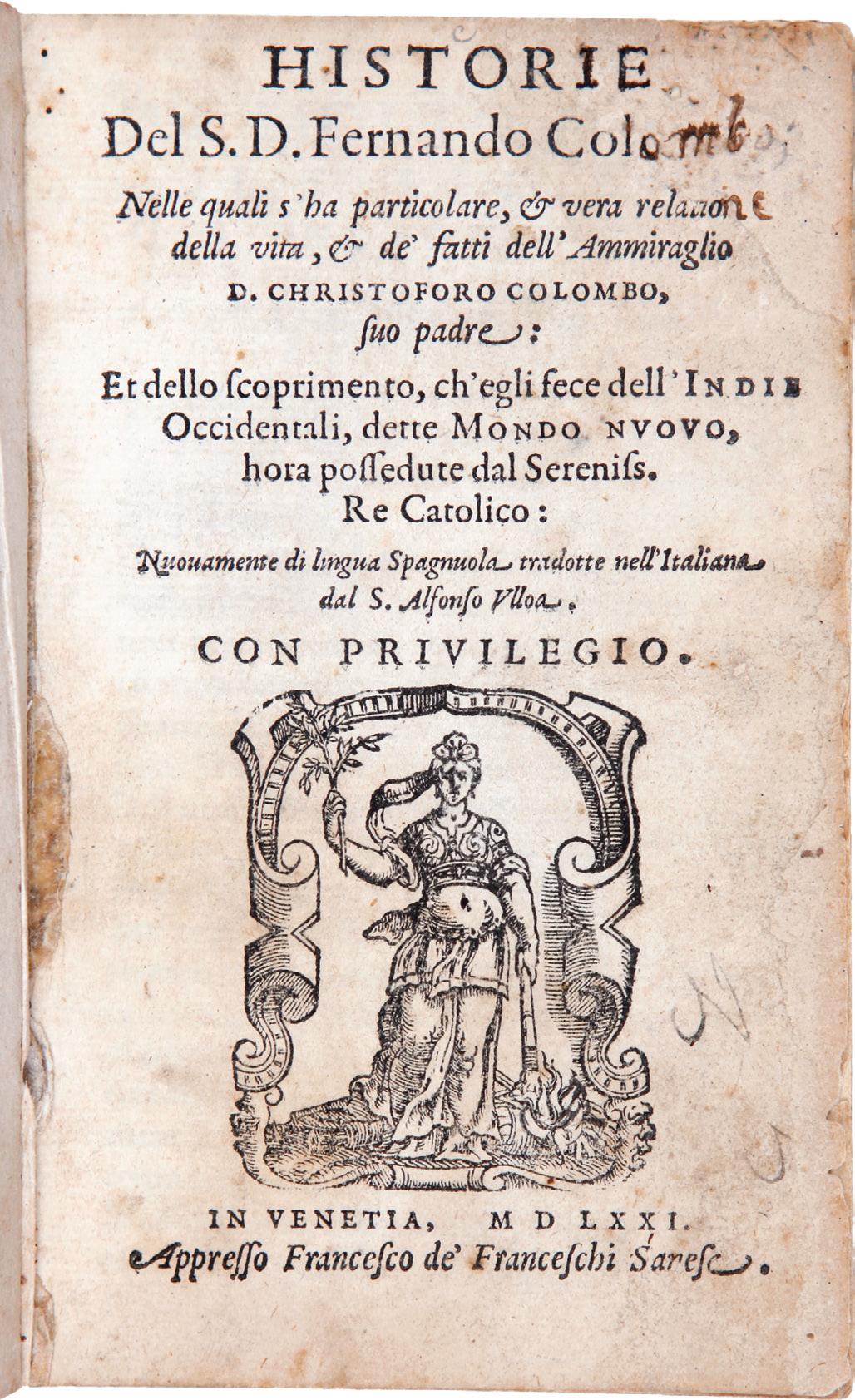

ISTC locates thirteen copies worldwide, with but three in America (Smithsonian, Harvard, and NYPL). We find no other examples on the market in nearly a century.

European Americana 496/9; Goff L139 (locating Dibner & Harvard); Hain 4283. Emmanuel Poulle, Les instruments de la theorie des planetes selon Ptolemy (Droz, 1980). SOLD

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 11

THE FIRST DATED BOOK ON SYPHILIS: WRONGLY THE FRENCH DISEASE, ITS AMERICAN ORIGINS SINCE CONFIRMED

4. GRÜNPECK DE BURCKHAUSENN, Joseph. Tractatus de pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos Originem Remediaque eiusdem continens co[m] pilatus a vene rabili. [Leipzig: Gregorius Böttiger, after 18 October 1496.]

Quarto (205 × 155 mm): a–b 6; [12] leaves. Later vellum. Vellum lightly soiled and wrinkled. Very clean internally.

A medical incunable of note, Grünpeck’s work is among the earliest dated works to discuss syphilis, perhaps the earliest global epidemic. Cases arrived in Europe with the return of Columbus from his first voyage in 1493 and quickly spread among the army of Charles VIII after the French king invaded Naples. Although over the years some have doubted the Columbian exchange theory as to the origin of the epidemic, modern genetic analysis has all but confirmed the American origins.

The work is a commentary by Grünpeck, the secretary of Emperor Maximilian, on a broadside poem of Sebastian Brandt; the text of this poem is included here, along with an extensive discussion of the astrological causes of the disease. According to Garrison and Morton, Grünpeck was “the first to record mixed primary lesions, multiple primary lesions, and to note the second incubation period of syphilis.”

The work appeared in six editions all in late 1496 and early 1497, in either Latin or German, the former with an additional introduction regarding treatment. All editions are scarce; we note the last example on the market being sold by H. P. Kraus in his famed catalogue Americana Vetustissima (cat. 185, item 3).

BMC III 648; Bod-Inc G-259; BSB-Ink G–385; European Americana 496/8; Goff G515; GW 11571; H 8093*; ISTC ig00515000.0; Klebs 476.3; Walsh 828.

$45,000

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 12

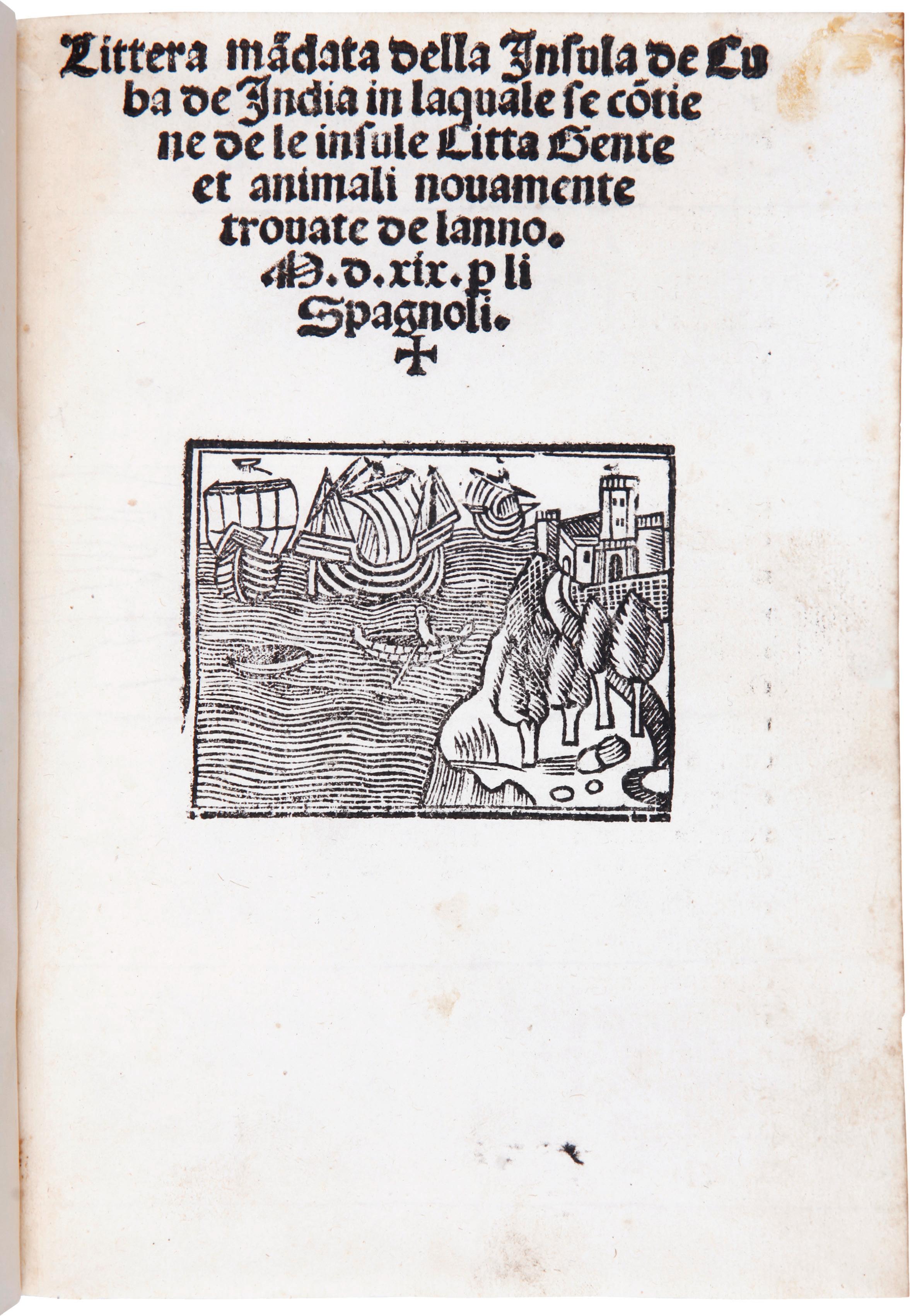

THE DISCOVERY OF THE NEW WORLD AND THE FIRST ACCOUNT OF BRAZIL

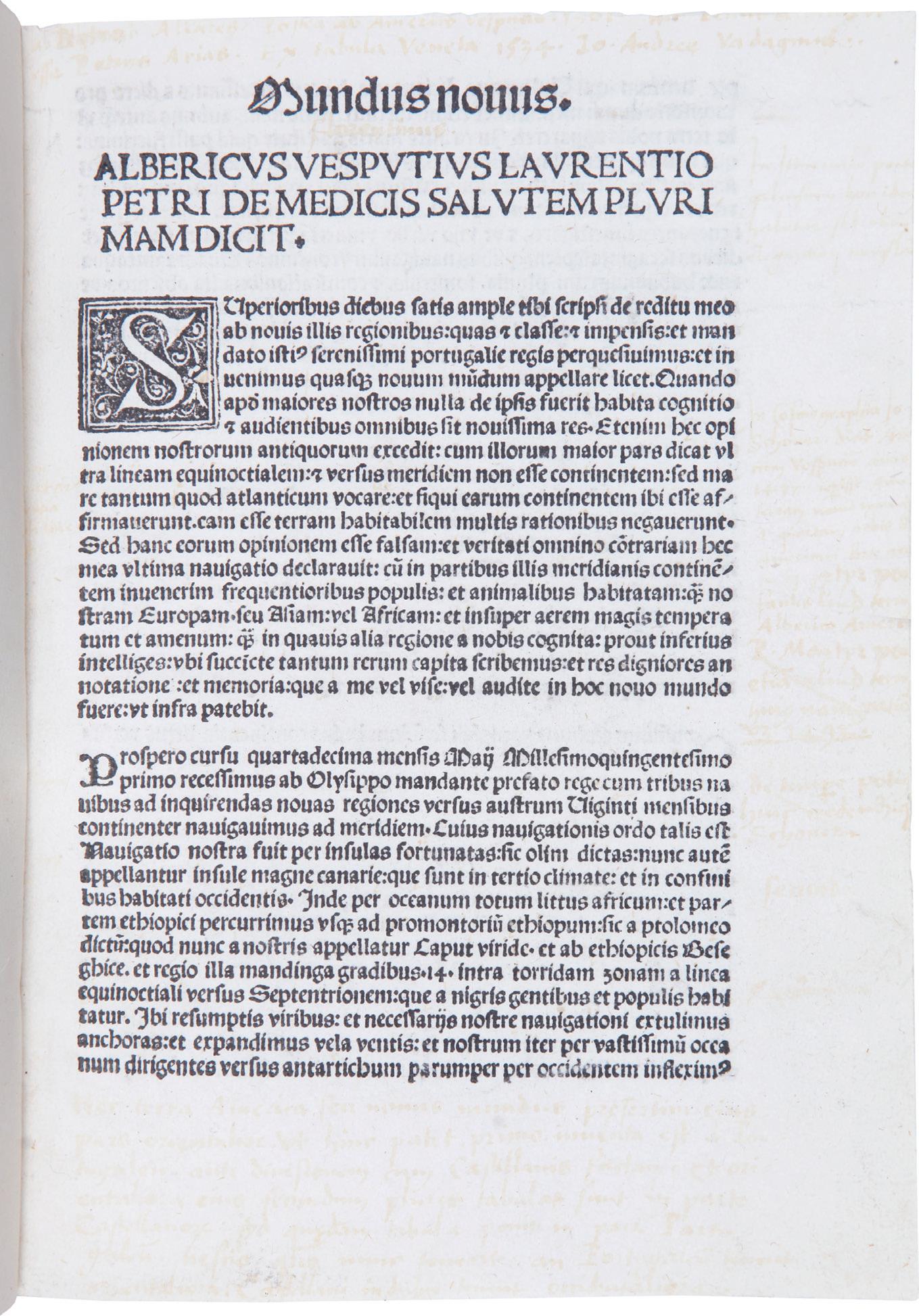

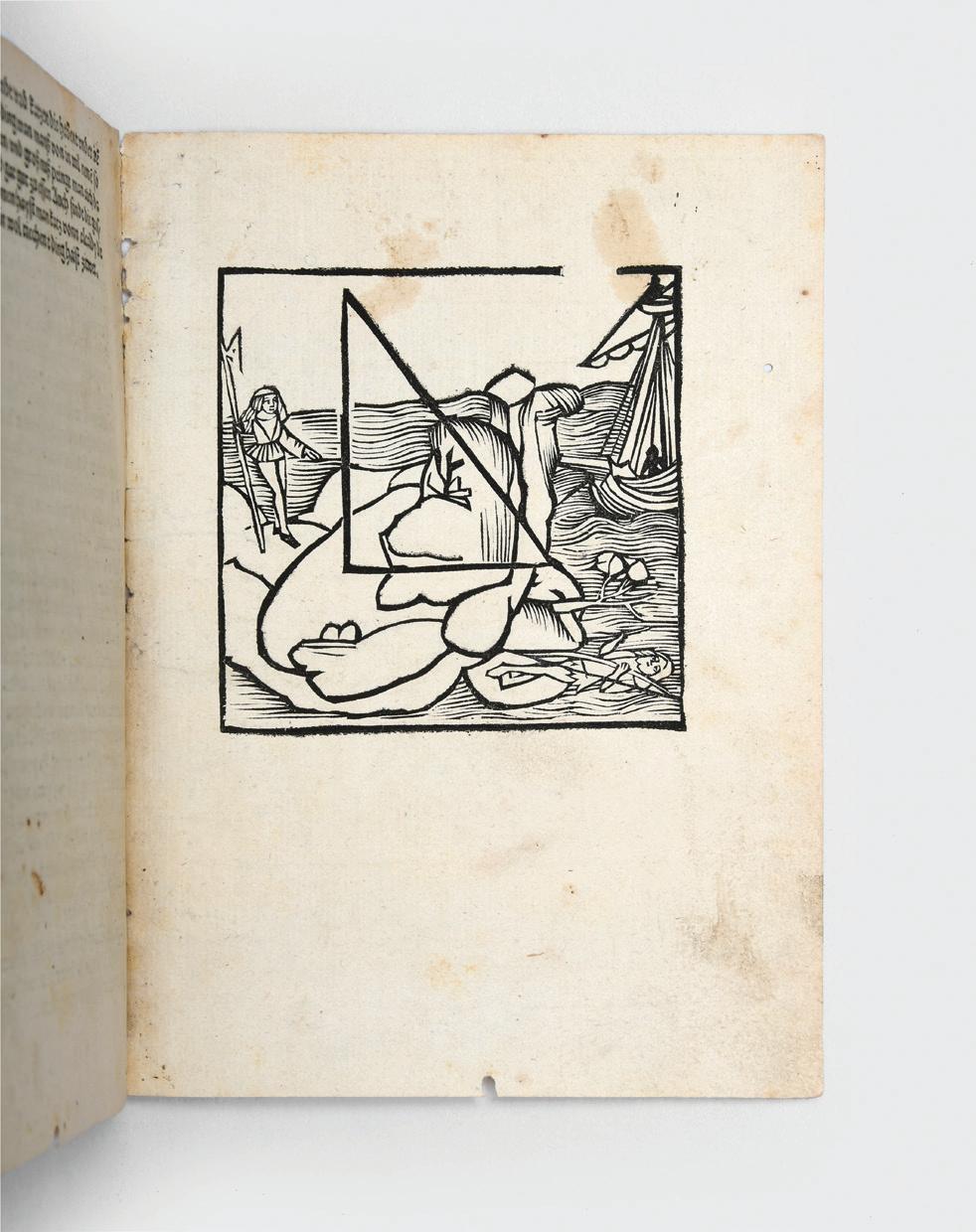

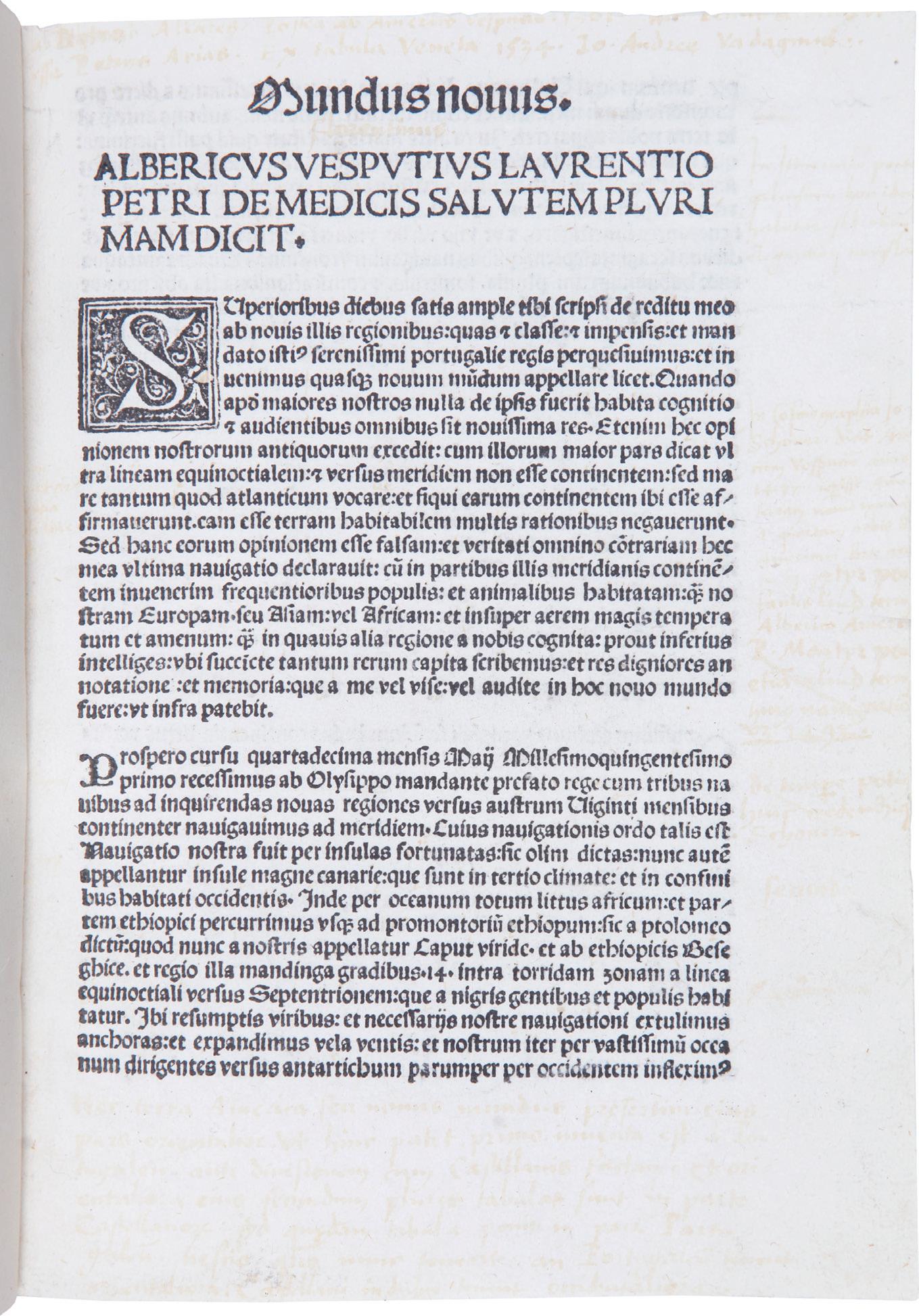

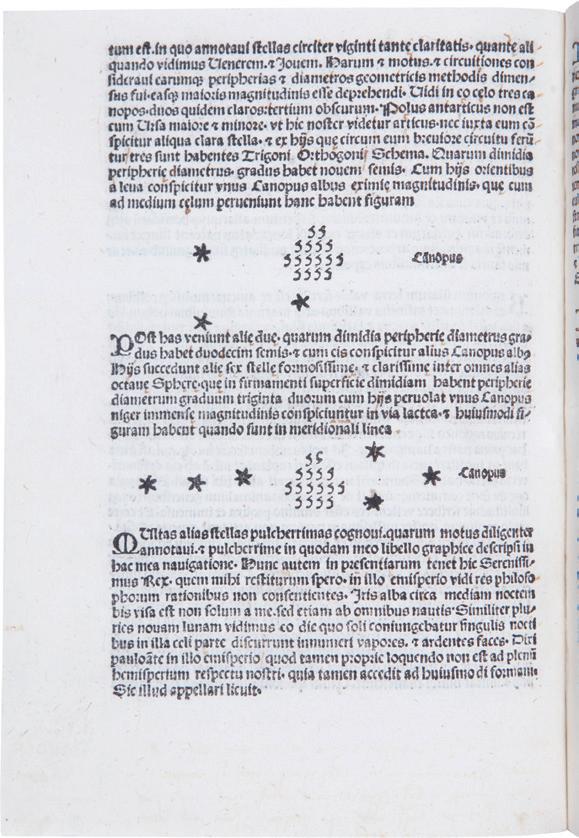

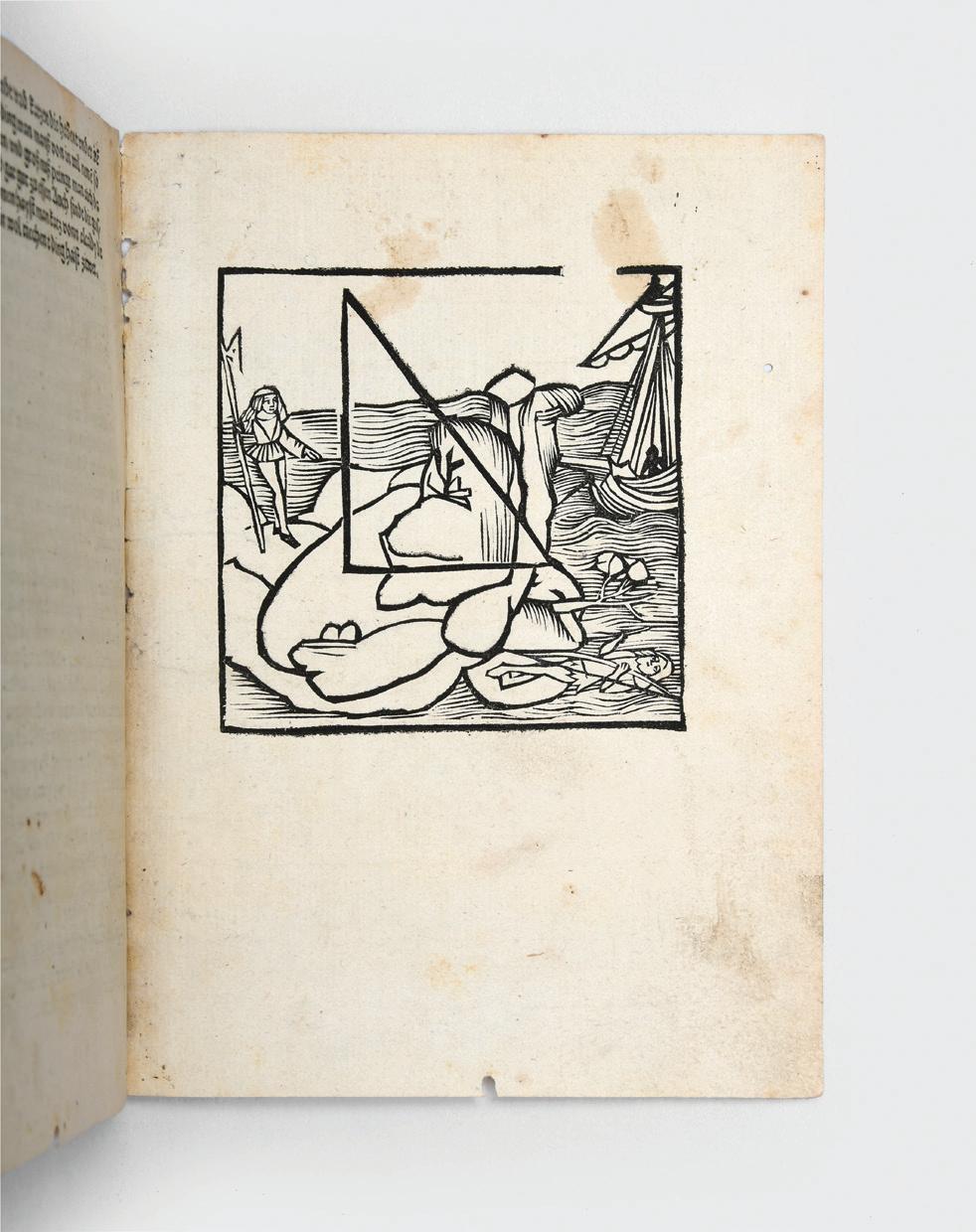

5. VESPUCCI, Amerigo. Mundus Novus. Rome: Eucharius Silber, 1504.

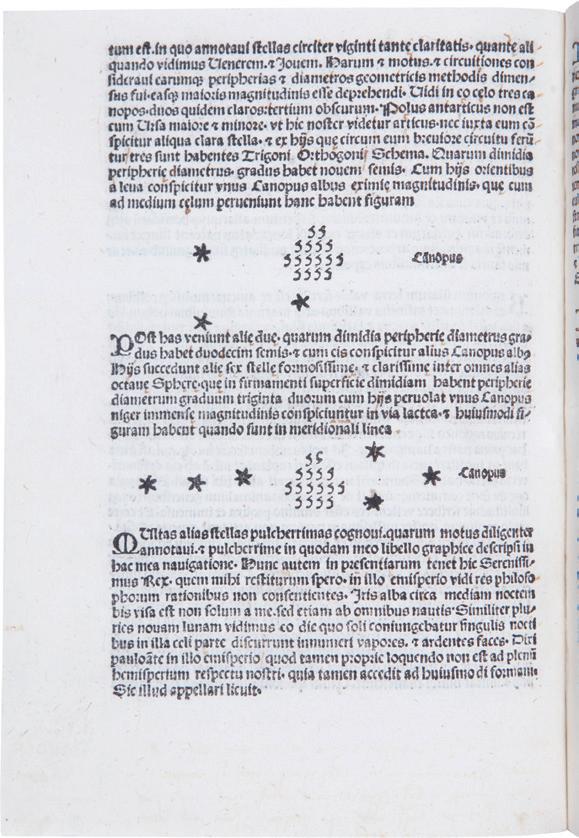

Small quarto (190 × 136 mm): [4] leaves. Two woodcut initials, two schematic representations of constellations, and a woodcut diagram. Extensive near-contemporary marginalia, significantly faded (see below). Bound in modern black crushed morocco, ruled in blind, spine with raised bands. In a half morocco and cloth clamshell case, spine gilt. Washed. First letter mis-inked in “[c]ognitione” on recto of leaf A2.

A primary account of the discovery of the New World, indeed the first to describe it as such, Mundus Novus is the first printed account of Brazil, and Vespucci’s first published work about his American voyages.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 13

A rare and important Americanum by the man after whom the Americas would be named, this epistolary work comprises the “first existing printed document about Brazil” (Borba). The letter to Vespucci’s patron Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici describes his voyage along the coast of Brazil carried out in the service of King Emmanuel of Portugal between May 1501 and September 1502. This voyage under the Portuguese flag is of fundamental importance in the history of geographic discovery, convincing first Vespucci and then those who read his letter that the newly discovered lands were not part of Asia but a New World. In this sense, Vespucci was the first to proclaim the true significance of the discovery.

During this voyage Vespucci became the first European to see the Río de la Plata, and sailed along the coast of Patagonia, possibly reaching as far as 50 degrees south. Spending almost a month ashore, Vespucci met indigenous peoples, whom he described as naked cannibals wearing colorful ornaments in their perforated ears, noses, and lips. He also described houses, hammocks, customs, and eating habits, and detailed animals and plants, some of which he compared to those in the Old World and others that were wholly new. Likewise, he observed that the very sky of the Southern Hemisphere was different. Indeed, Vespucci was the first astronomer to measure the positions of the most important southern stars and his brief descriptions of them, together with his star diagrams, appear for the first time in this work.

Vespucci (1454–1512), a Florentine merchant, first went to Barcelona in the employ of the Medicis in 1489, and to Seville in 1493. Probably involved in equipping the ships for Columbus’s second voyage, Vespucci went on voyages in 1497 and 1499 under the Spanish flag, commissioned for his knowledge of astronomy and his navigational skills. Following the success of his third voyage, under the Portuguese flag, in 1508 he was appointed Spain’s piloto mayor (chief navigator). “The brilliant pamphlets that circulated about his adventures in the West made him the reputation that his voyaging could not” (Grafton, p. 83).

While none of the early editions bear imprints, Sabin, European Americana, and Borba consider this to be the fourth Latin edition, reprinted from the second issue of the second edition (Venice). The type was identified by Dr. Joseph Martini as being “the same as [that] used by Silber in the letter of Columbus (1493).” The Mundus novus was republished throughout Europe with the rapidity of a news sheet, appearing at least twelve times during Vespucci’s lifetime in Latin, several times in German and French, as well as once in both Dutch and Czech. “The alterations of text made in this edition, combined with the alterations of the Venice edition, served as the basis of all the later Latin editions printed at Nuremberg, Strassburg, Rostock, Cologne, Antwerp, and Paris. It was the first to appear without a separate title page, the words Mundus nouus being placed at the head of the first page. The spelling of Vesputius with a ‘t’ was adopted for the first time . . . and the triangle was moved from its right position under the eighth paragraph [to the verso of the final leaf] under Lavs Deo. Typographically it is a fine piece of printing, and with few word contractions” (Wilberforce Eames in Sabin).

“A pamphlet that enjoyed such great success in the sixteenth century, that was reprinted so frequently, commented upon and analyzed, that was and still is the object

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 14

of a centuries old polemic, could not but be of enormous bibliographical interest. To this must be added the fact that any of the editions or translations are very rare, dated or undated. It has been avidly sought after by bibliophiles for more than a century and a greater part of the copies are already in public libraries” (Borba).

This is an unusual copy for being extensively annotated in Latin in a sixteenth-century hand. Discovery Americana of this rank rarely contains any evidence of contemporary or near-contemporary reception or context. The annotations have faded from washing, but they can be read under close inspection. On the first page, the reader notes that Vespucci came from Florence (“Florentinus” appears above Vespucci’s name in the salutation) and in the cropped note above the text he sets Vespucci’s work into a chain of discussions that begins with Pierre d’Ailly, whom

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 15

Columbus famously read. References to other authors in the annotations include several mentions of Peter Martyr as well as astronomer Johannes Schöner.

Several of the manuscript annotations would seem to suggest that the early reader had access to maps of the world depicting America. For example, he names Vespucci’s reference to the “angle of land” as “promontorium sanctae Crucis,” perhaps referring to the name given to South America in the map of the world on Benedetto Bordon’s oval projection contained in the Isolario of Bartolomeo da li Sonetti. Recording in the margin next to Vespucci’s description of the nakedness of the indigenous inhabitants, he writes: “Nudi. quia sub torrida zona” (“Naked, because [they are] under the torrid zone”). A lengthy annotation at the rear espouses the Ptolemaic relationship between geographic location and skin color: “Quaecumque igitur gentes subiacent Zodiaco, praeterquam in Sphaera armillari, iis sol sit supra verticem a Borea descendens ad austrum, ascendensque similiter, et aliis quidem semel in anno, aliis vero bis. Sunt autem omnes pariter qui sub Zodiaco habitant ab occasu ad ortum solis usque nigri, coloribus Aethiopes, et praecipue hi qui sub circulo aequinoctiali habitant, ii admodum nigrescunt. Qui autem extra lineam perpendicularem Zodiaci degunt remissiores sunt colore, et in albedinem tendunt, secundum distantiae rationem, usque ad Sarmatas Hyperboreos. Eadem est ratio Zodiaci ab utraque parte equinoctialis, et Boream versus et Austrum, usque ad utrosque polos.” (“Whichever nations, then, are subject to the Zodiac, except those who are girdled in the Sphere, for them the sun is above the summit descending from Borea to the south, and rising in the same way, and for some once a year, but for others twice. Now all those who live under the Zodiac from sunset to sunrise are black in color, Ethiopians, and especially those who live under the equatorial circle are very black. But those who live outside the perpendicular line of the Zodiac are lighter in color, and tend towards whiteness, according to the distance, as far as the Sarmatians and the Hyperboreans. The system of the Zodiac is the same on both sides of the equator, and towards Borea and the South, as far as both poles.”) Many other annotations are worthy of further research.

A foundational Americanum, announcing the discovery of the New World, and an outstanding rarity.

Borba de Moraes pp. 904–9; Brunet V.1154, Suppl. II.873; Church 17; European Americana 504/8; Harrisse (BAV) 23; JCB (3) I, p. 40; Medina (BHA) 22; Portugal-Brazil, pp. 237–40; Sabin 99331; Warner, Sky Explored, p. 225. See also Robert Wallisch, Der “Mundus Novus” des Amerigo Vespucci (Vienna, 2002).

$425,000

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 16

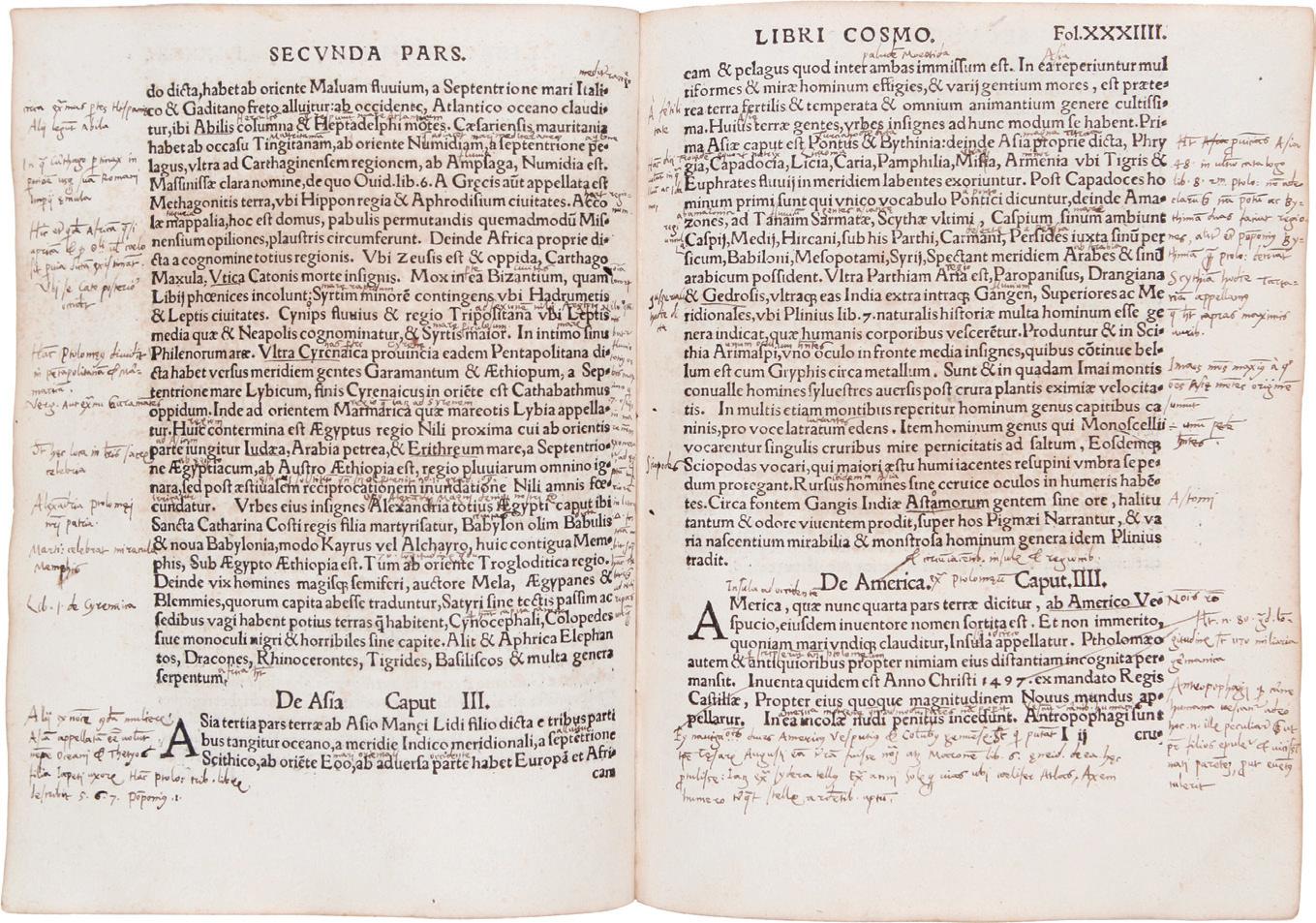

FIRST WORK PUBLISHED IN POLAND WITH A REFERENCE TO AMERICA

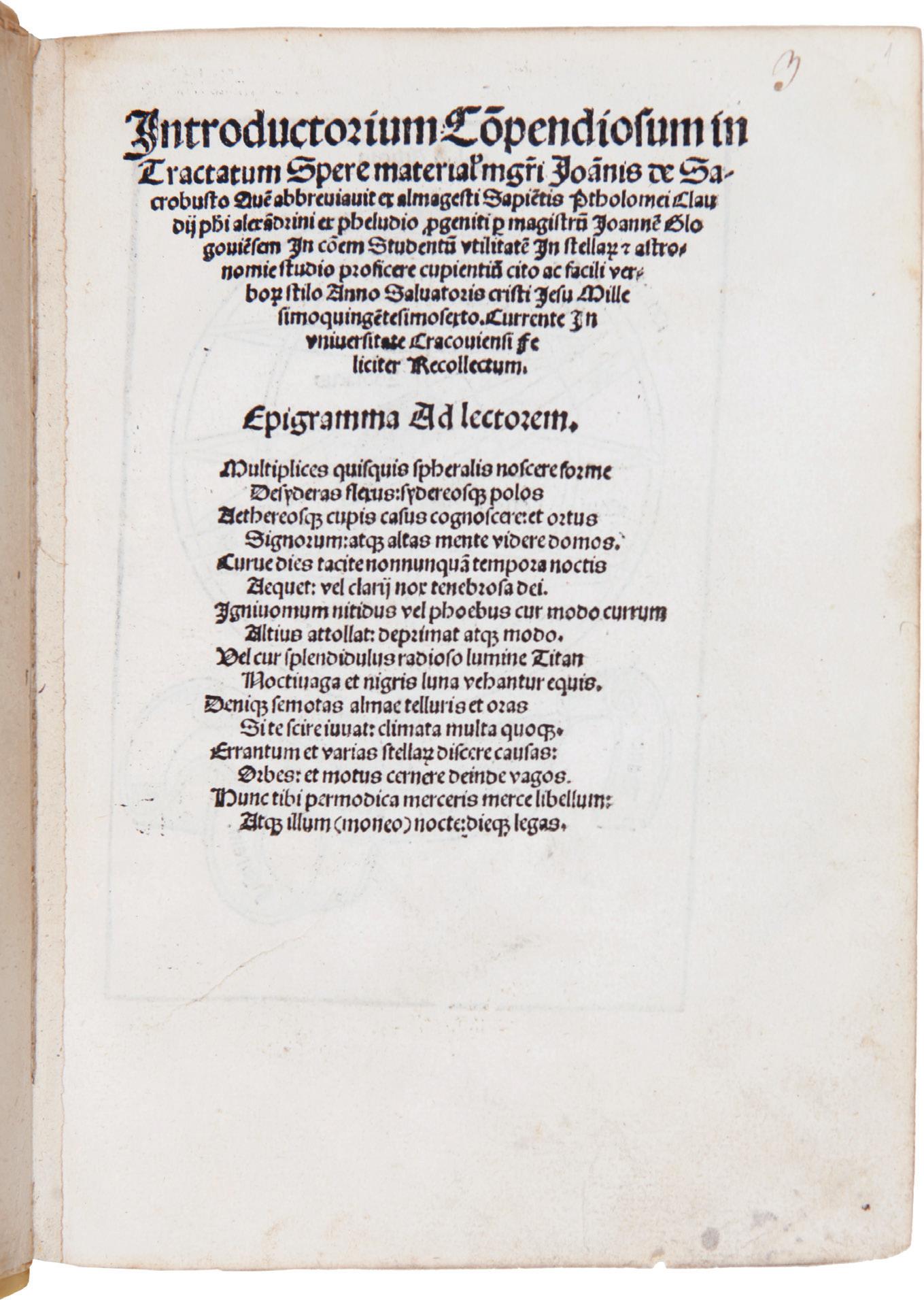

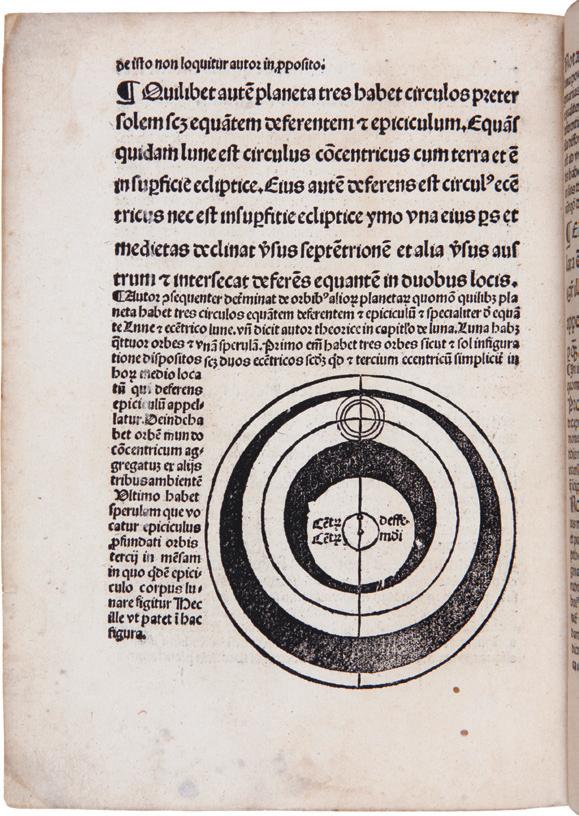

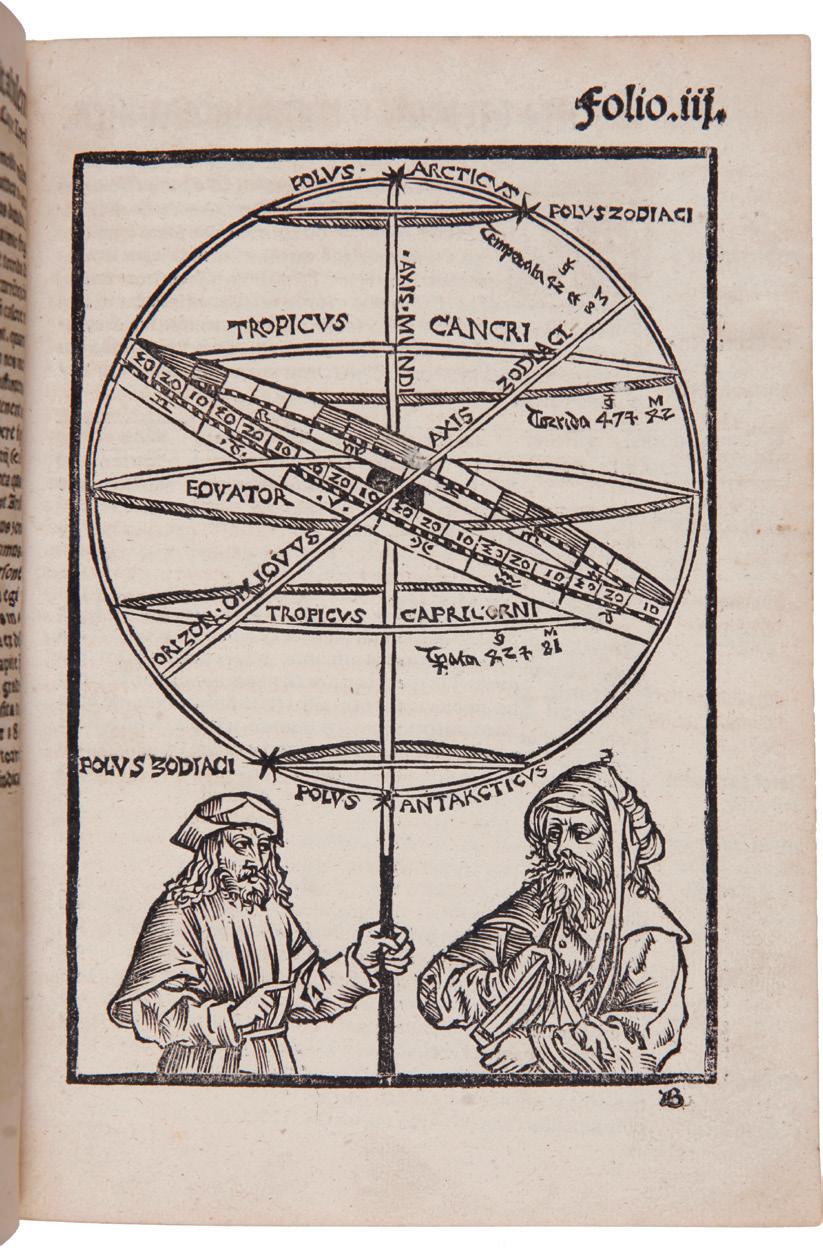

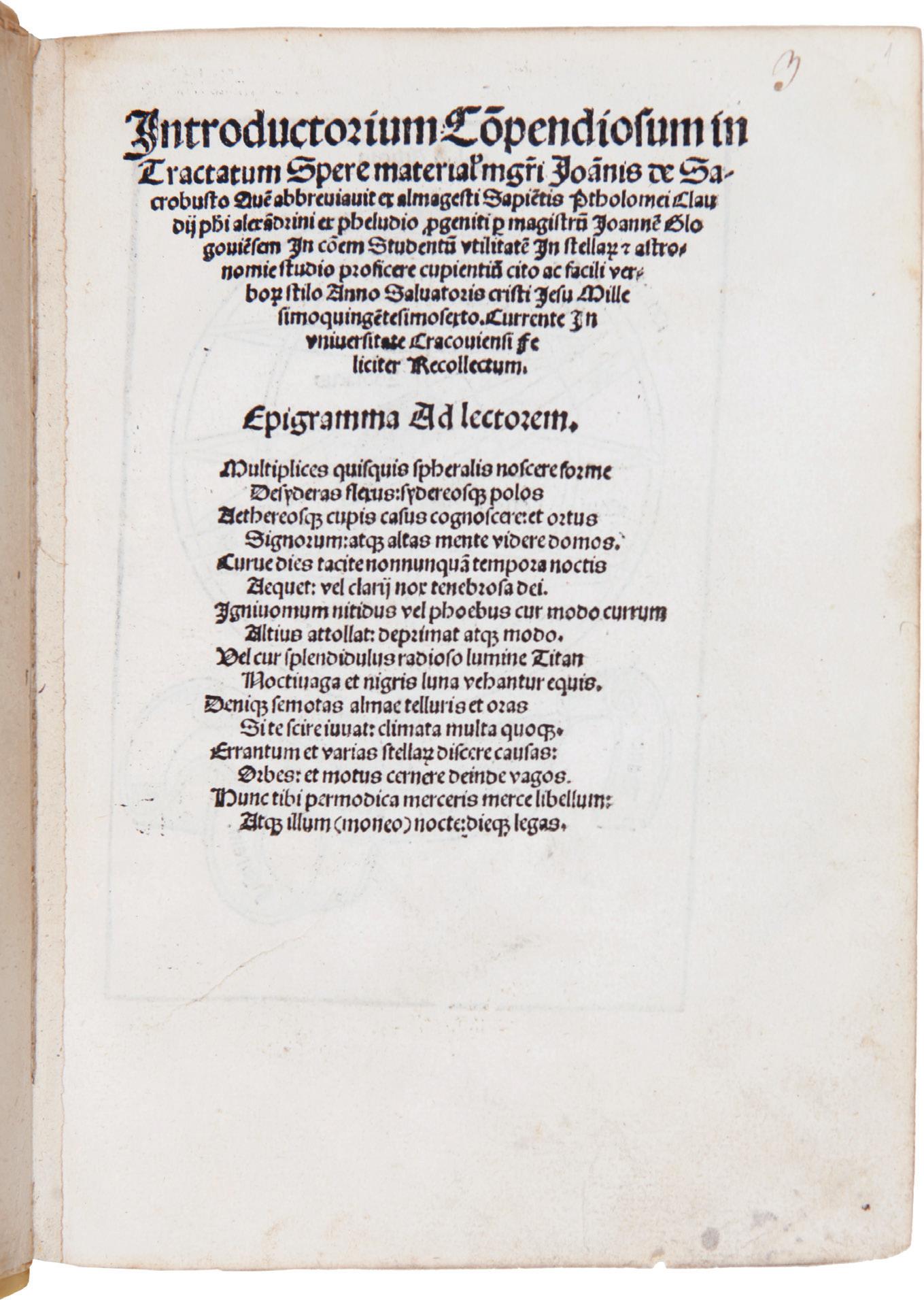

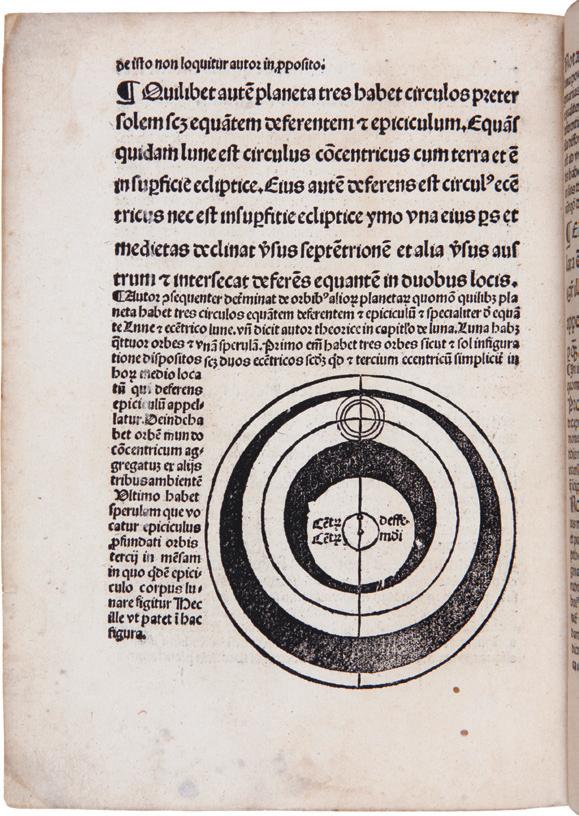

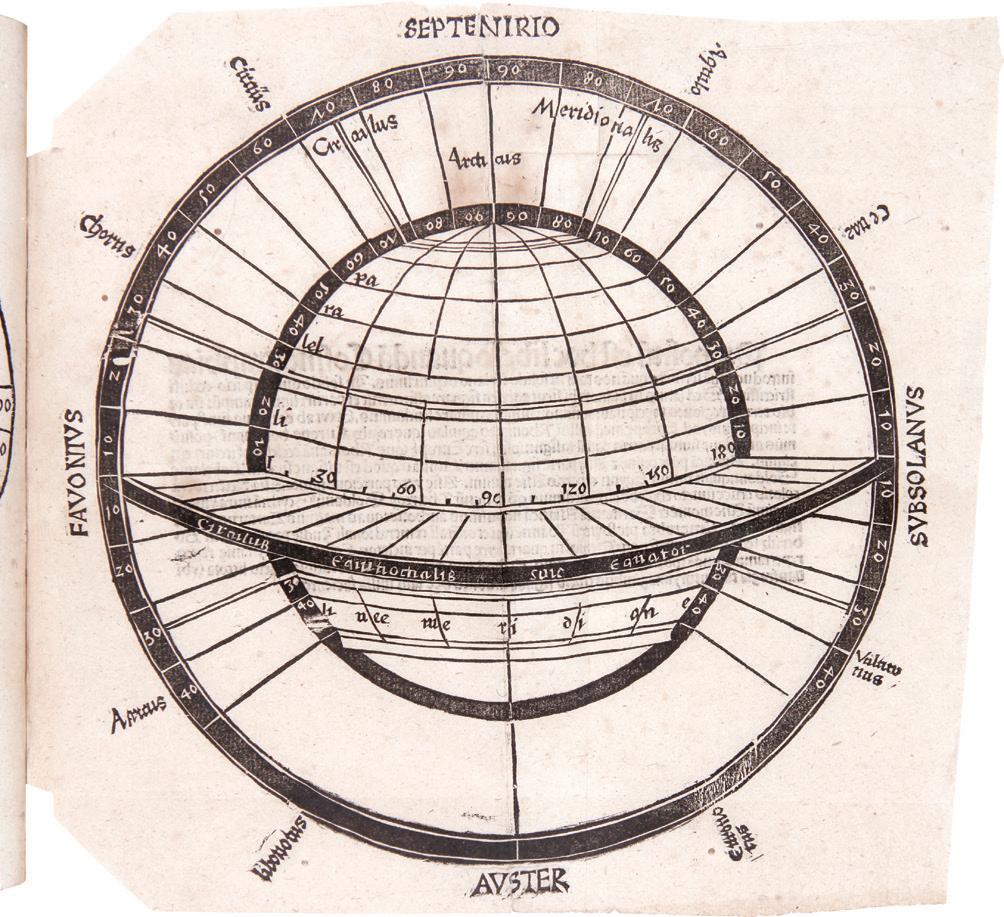

6. GLOGOVIENSIS, Joannes [Jan Glogowczyk]. Introductorium compendiosum in tractatum spere materialis magistri Joannis de Sacrobusto. Krakow: Jan Haller, 28 April 1506.

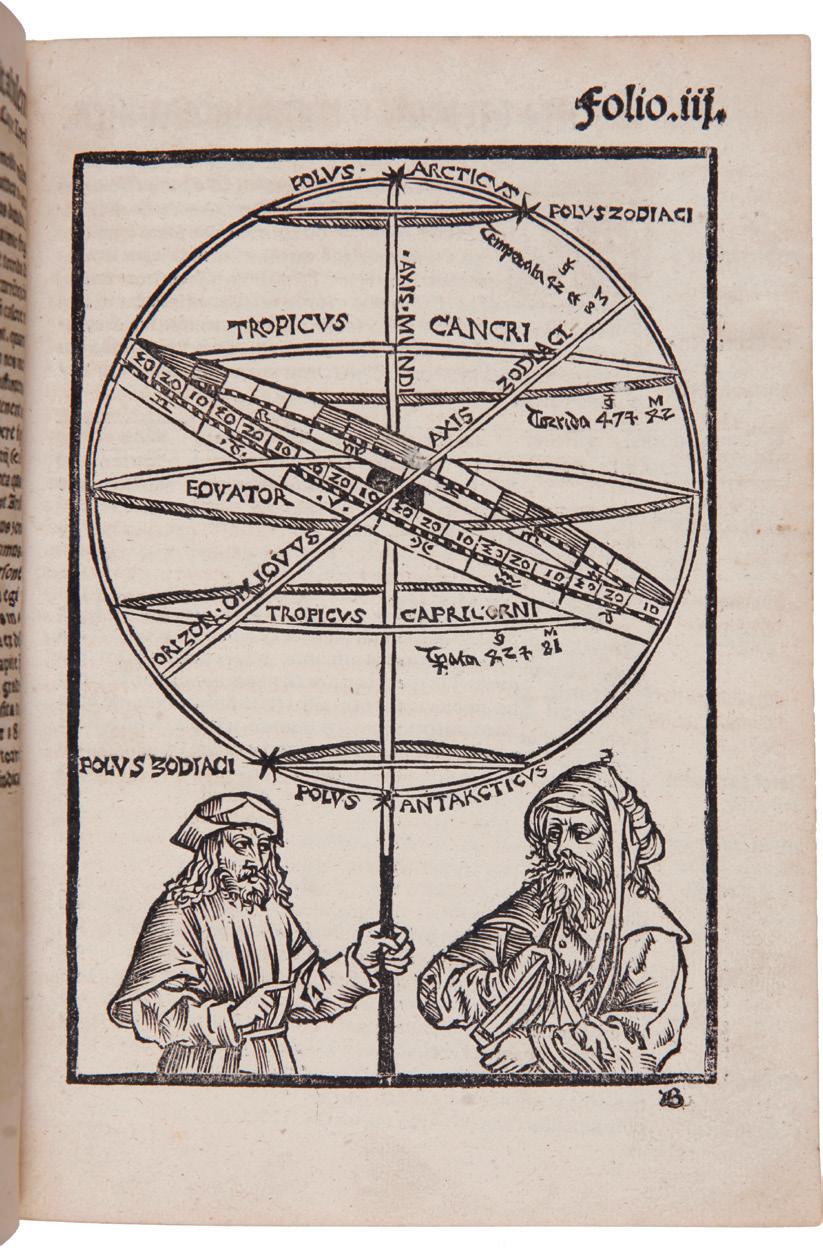

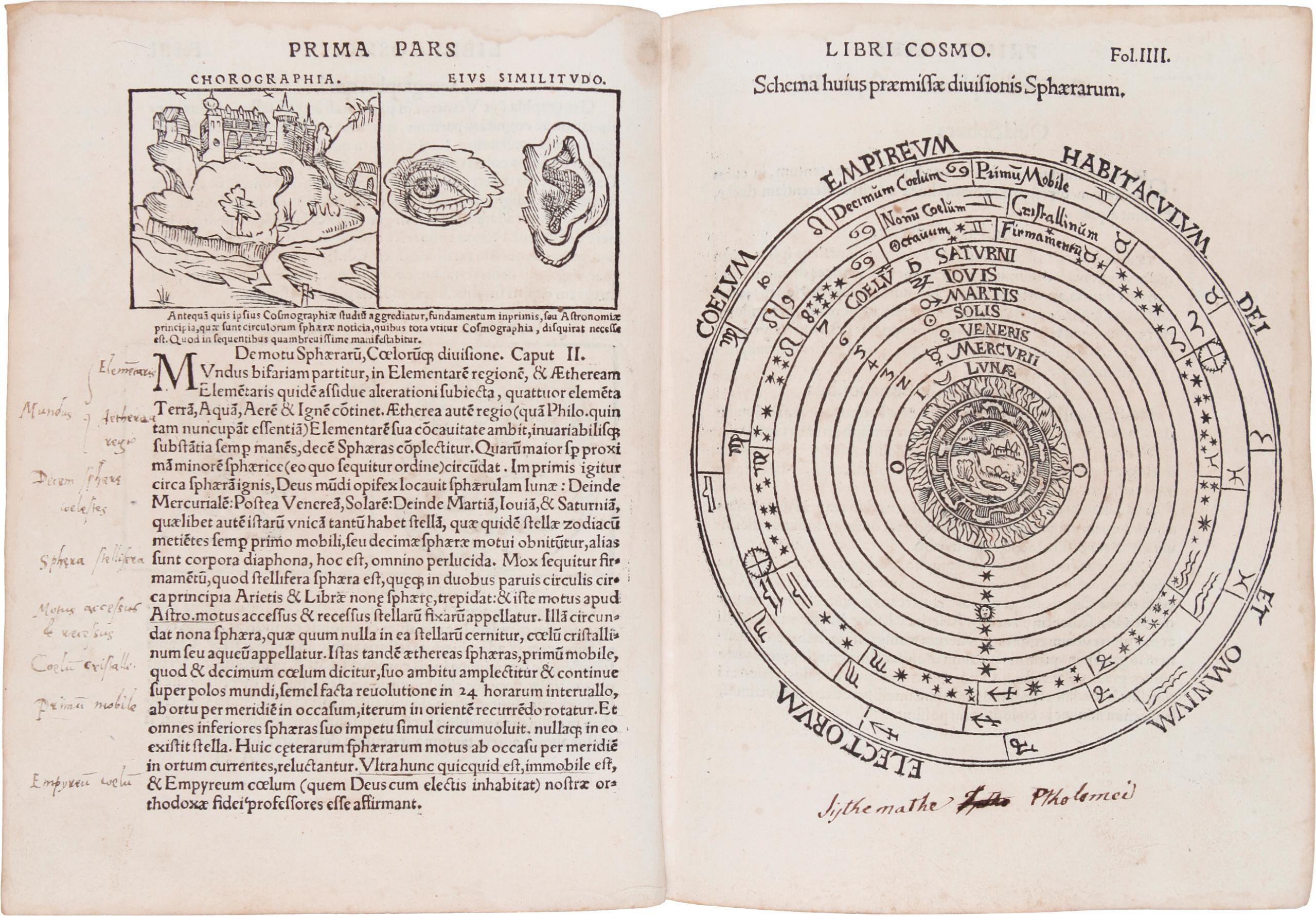

Quarto (210 × 155 mm): a–m 6; [72] leaves. Full-page woodcut armillary sphere, a nearly full-page cut of Jesus and his devotees presiding over the seven planetary zodiacs, a full-page table of solar declinations, and twelve woodcuts in text. Some contemporary manuscript annotations. Modern vellum over boards. Vellum bowed. Light staining in margin of some leaves, minor dampstaining extending from top gutter margin to a few signatures, final leaves toned, repairs to lower outer corners of the final few leaves. About very good.

Glogoviensis (1445–1507) published many works on astronomy, logic, and grammar for the use of students. He taught at the University of Krakow, and on that basis is postulated as a possible teacher of Copernicus. Jan Haller was the most prolific printer in Krakow at this time and published Copernicus’s first published work, a translation of Theophylact in 1509, and printed another edition of Glogoviensis’s treatise in 1513.

This scarce work, however, is the first title printed in Poland that mentions the discovery of America. On G2 verso is a long passage of American interest, referring to the expeditions of Vespucci who the King of Portugal sent out to the New World in 1501 and in 1504 to discover the location and number of its islands. Refuting Sacro Bosco’s claims relating to the habitability of the torrid zones, he writes: “And the same thing is confirmed by those who in the year 1501 and similarly in the year 1504 were sent by the King of Portugal to discover the origin of pepper and other aromatic spices. They sailed beyond the equator and saw both celestial hemispheres and their stars and they found the origin of pepper in a place which they called the New World which was hitherto unknown.” On I4 recto is another long passage referring to the inhabitants and climate of the newly discovered lands.

Scarce: European Americana locates seven copies, though only a single example appears in the auction records for the last half century.

European Americana 506/6 (catalogued under Sacro Bosco); Yarmolinsky 10; Zinner 867.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 17

SOLD

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 18

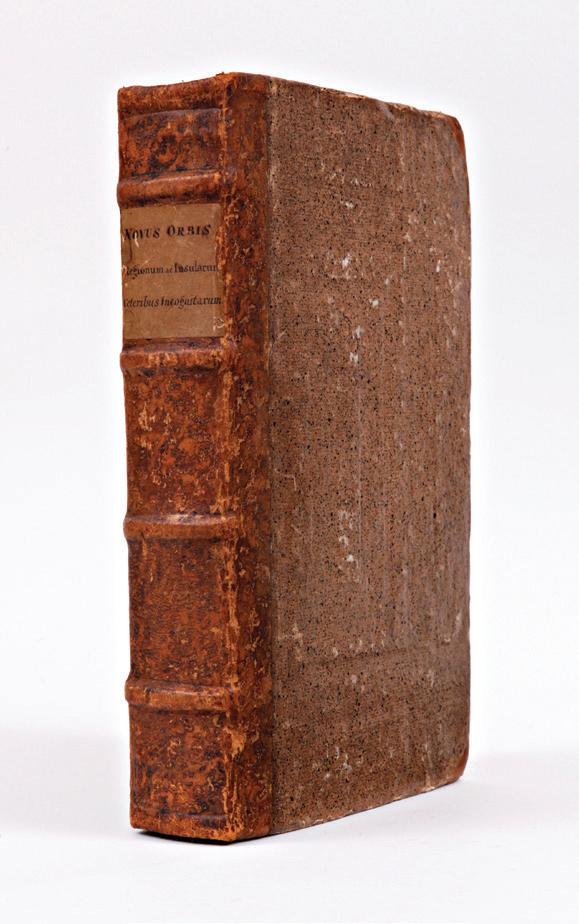

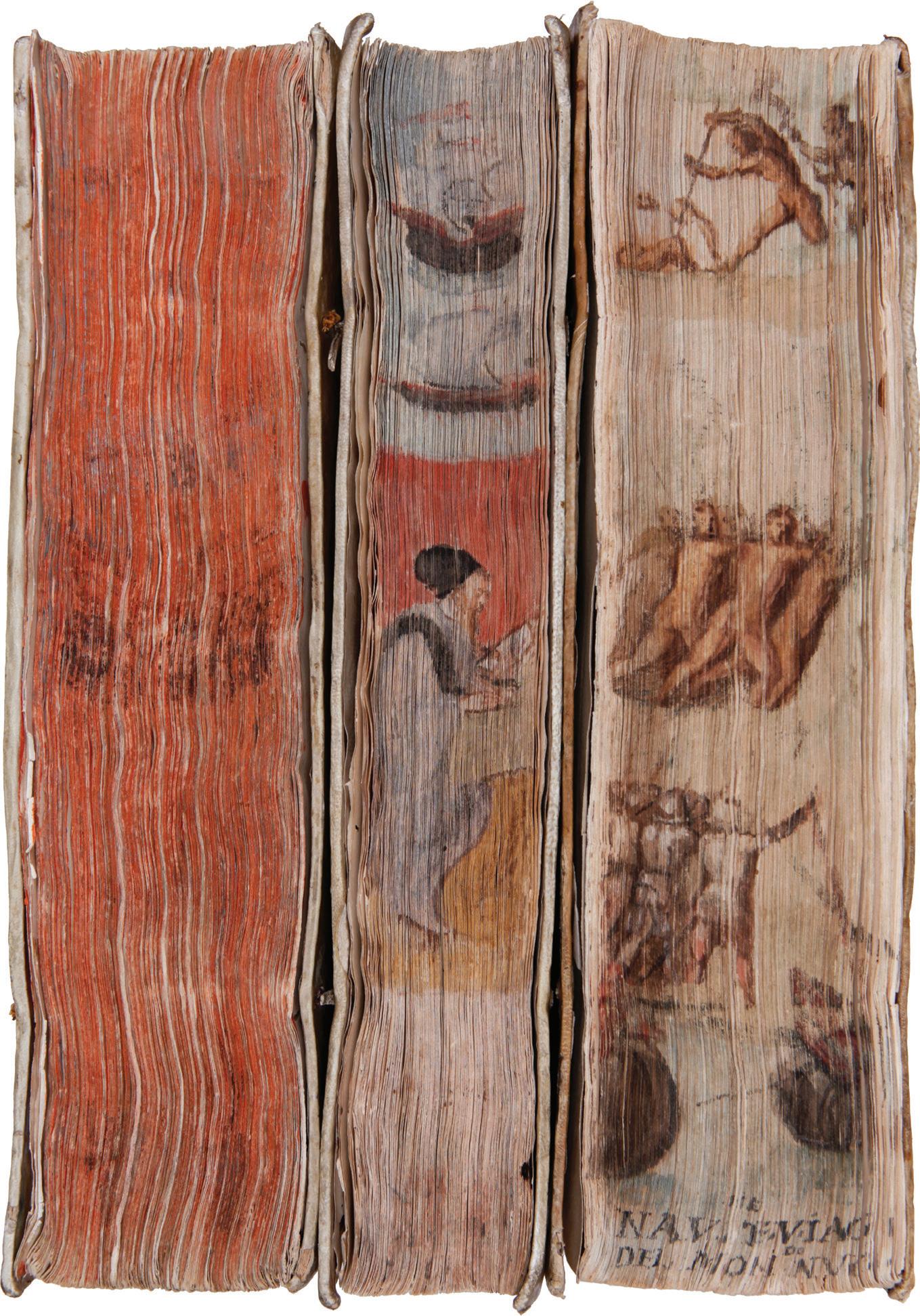

“AFTER COLUMBUS’S LETTERS, THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT CONTRIBUTION TO THE EARLY HISTORY OF AMERICAN DISCOVERY”—SABIN

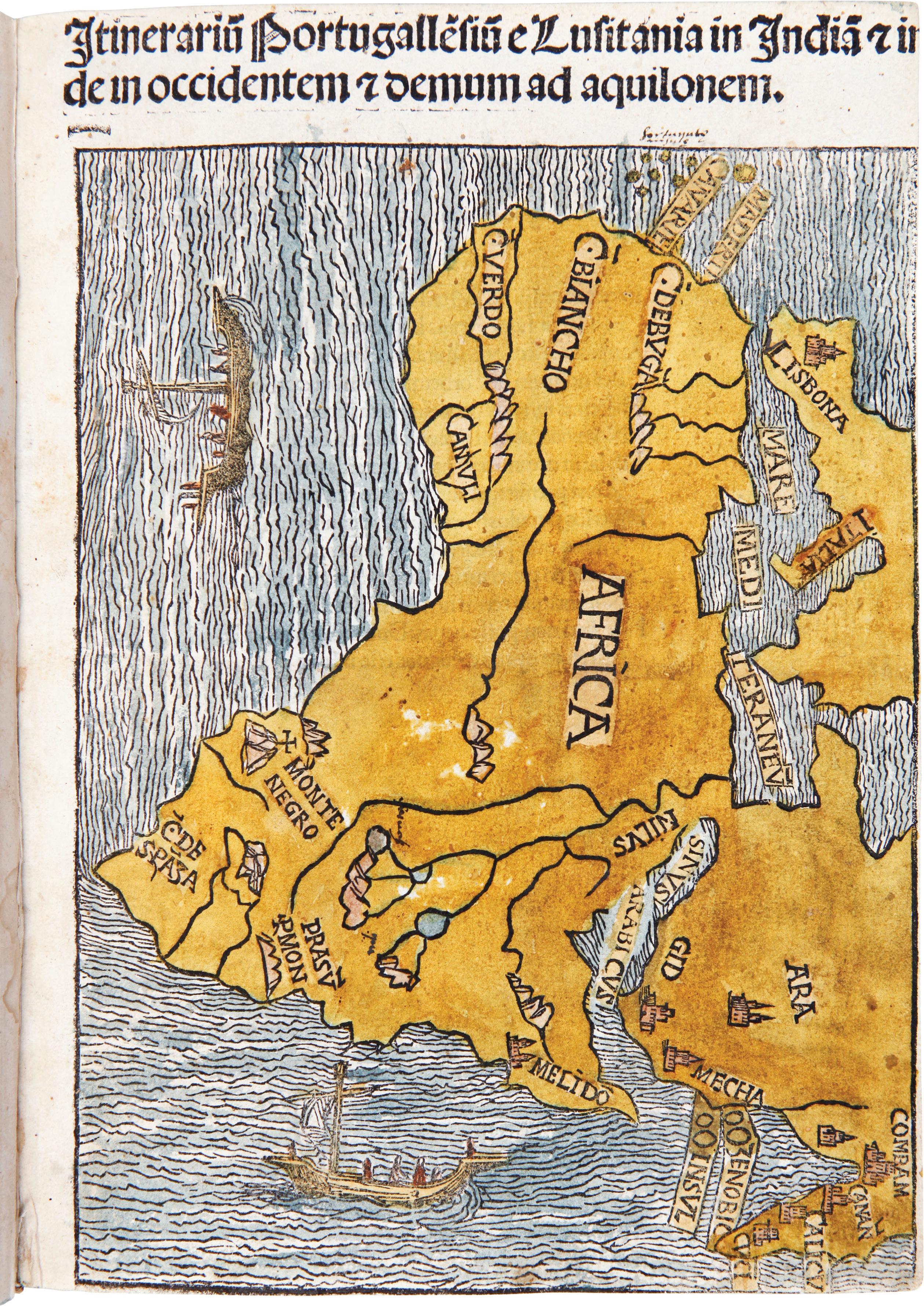

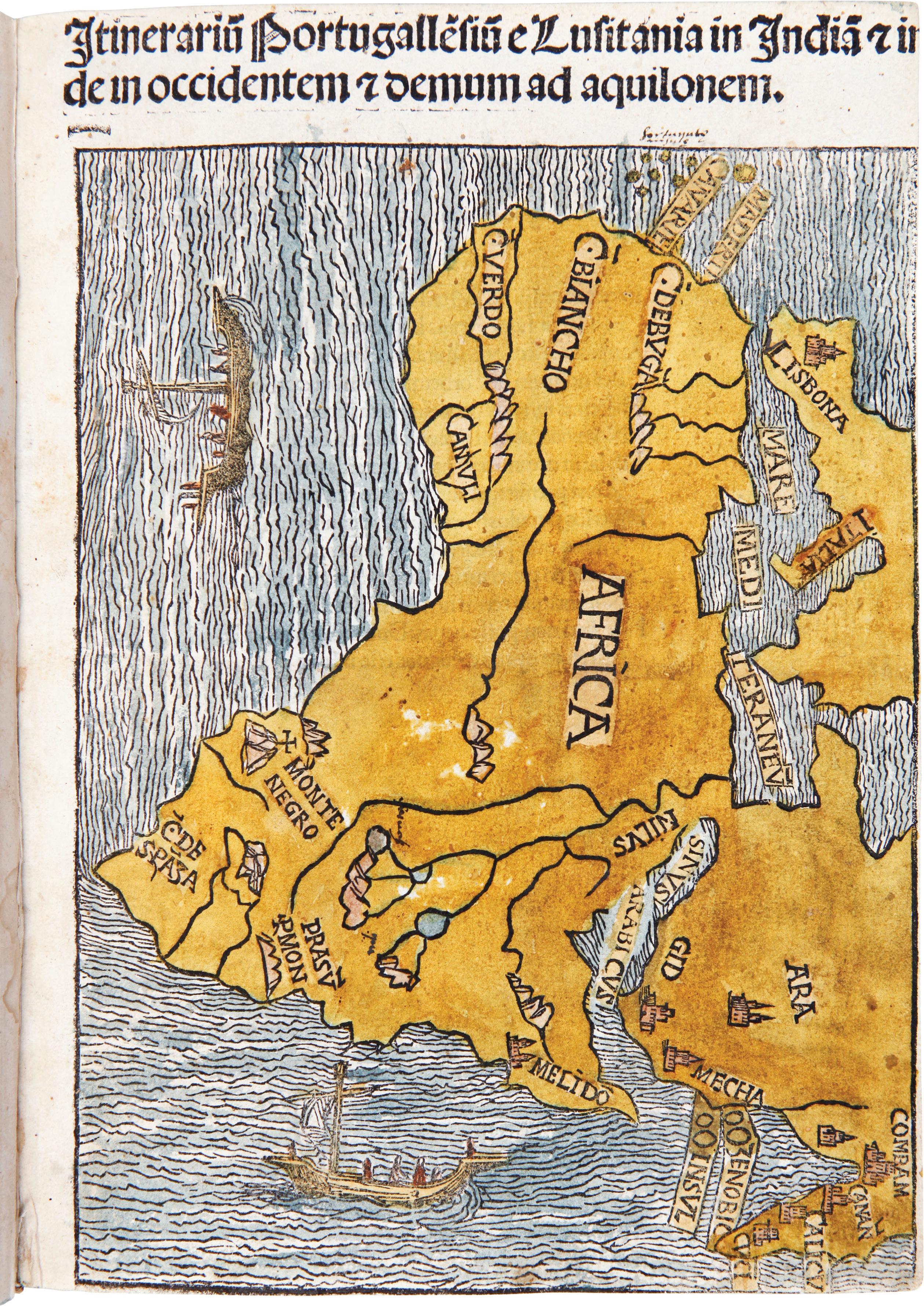

7. FRACANZANO DA MONTALBODDO. Itinerarium Portugallensium e Lusitania in Indiam et in de in Occidentem et demum ad aquilonem. Milan: J. A. Scinzenzeler(?), 1508.

Small folio (250 × 178 mm): A–C 8 D 6 E–F 8 G 6 H 8 I 6 K–M 8 N 6 2a 2 (index); [10], LXXVIII [i.e., 88] leaves, with errors in foliation as issued. 10- and 3-line woodcut initials. Three woodcuts and three-quarter page woodcut map of Africa and Arabia on title, the map hand-colored at an early date. Bound in old vellum manuscript over pasteboard, a few tears to spine exposing block, but sound. Housed in quarter morocco and linen box. Right margin of title trimmed close, just grazing final letter of first line to woodcut border, occasional light spotting and soiling, small dampstain in gutter of scattered leaves. Overall, an extremely fresh, unsophisticated copy. A. M. von Birckholz (bookplate on front pastedown); Mittel Rheinisch Reichs Ritter Schafflichen Bibliothek (bookplate on verso of title).

First Latin edition of the first printed collection of voyages, considered “after Columbus’s letter the most important contribution to the early history of American discovery” (Sabin); this copy with the second state woodcut map on the title page naming the Arabian Gulf.

Fracanzano (or Fracanzio) da Montalboddo (fl. 1507–1522) was an Italian humanist and university professor. For this seminal compilation, he collected reports of the voyages of Columbus, Vespucci, Cabral (Brazil), Cadamos (Africa), and the earliest printed account of the voyage of Vasco da Gama to India. The latter was first published in Italian in 1507 under the title Paesi novamente retrovati; this Latin translation, printed the following year, was made by the Milanese monk Arcangelo Madrignani, who also translated Varthema’s Itinerario (1510). It quickly became “the most important vehicle for the dissemination throughout Renaissance Europe of the news of the great discoveries both in the east and the west” (PMM).

The woodcut map, which appears for the first time in this Latin edition, is the first large map of Africa, the first known map in which that continent is depicted as surrounded by the ocean, as well as the earliest “modern” printed map to show Mecca. This is the corrected second state, distinguished by naming the Gulf as “Sinus Arabicus,” as opposed to “Persicus.” Also present is the rare two-leaf index, which is of crucial importance, as it gives an outline of the contents, identifying individual voyages and discoveries, whereas the text of the book runs continuously from section to section without distinguishing where a new one begins. These leaves were apparently printed after the publication of the work, inserted into the few available copies after the fact, and are therefore almost invariably missing.

The work, which contains six nominal sections, commences with the voyages of Alvise de Cadamosto in Ethiopia and along the West African coast. Cadamosto traveled to Senegal, Gambia, and the Cape Verde Islands in 1455 and 1456. This is followed by accounts of Pedro de Sintra’s expedition along the west coast of Africa as far as Sierra Leone in 1462; Vasco da Gama’s epochal voyage to Africa

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 19

and India (1497–99), which “opened the way for the maritime invasion of the east by Europe” (PMM), supplied by letters from Venetian spies in Portugal; and Pedro Alvares Cabral’s discovery of the Brazilian, Guianaian, and Venezuelan coasts in 1500. The third section is a continuation of the Cabral narrative of the voyage on to India. The fourth is an account of Columbus’s first three voyages (1492–1500), undoubtedly based on Peter Martyr’s Libretto de tutta la navigatione de Re de Spagna de le isole et terreni novamente trovati, as well as narratives of the expeditions of Alonso Niño and Vicente Yañez Pinzon along the northern coast of South America. The fifth is Vespucci’s letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici describing his third voyage in 1501–02. The sixth is a compilation of information derived from several sources concerning the Portuguese discoveries in Brazil and the East.

Montalboddo’s collected voyages is called by Henry Harrisse “the most important collection of voyages”; Boies Penrose asserted that “for news value as regards both the Orient and America, no other book printed in the sixteenth century could hold a candle to it.” The work was the forerunner of the later compilations of Grynaeus and Huttich, Ramusio, Eden, Hakluyt, the De Brys, and Hulsius, “an auspicious beginning to the fascinating literature of the great age of discovery” (Lilly Library online). “This book is not a jewel, it is a cluster of jewels” (Rodrigues).

Bell F169; Borba de Moraes p. 580; Church 27; European Americana 508/4; Harrisse (BAV) 58; JCB (3) I:46; LeClerc 2808; Penrose Sale 172; Printing and the Mind of Man 42; Rodrigues 1295; Sabin 50058.

$550,000

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 20

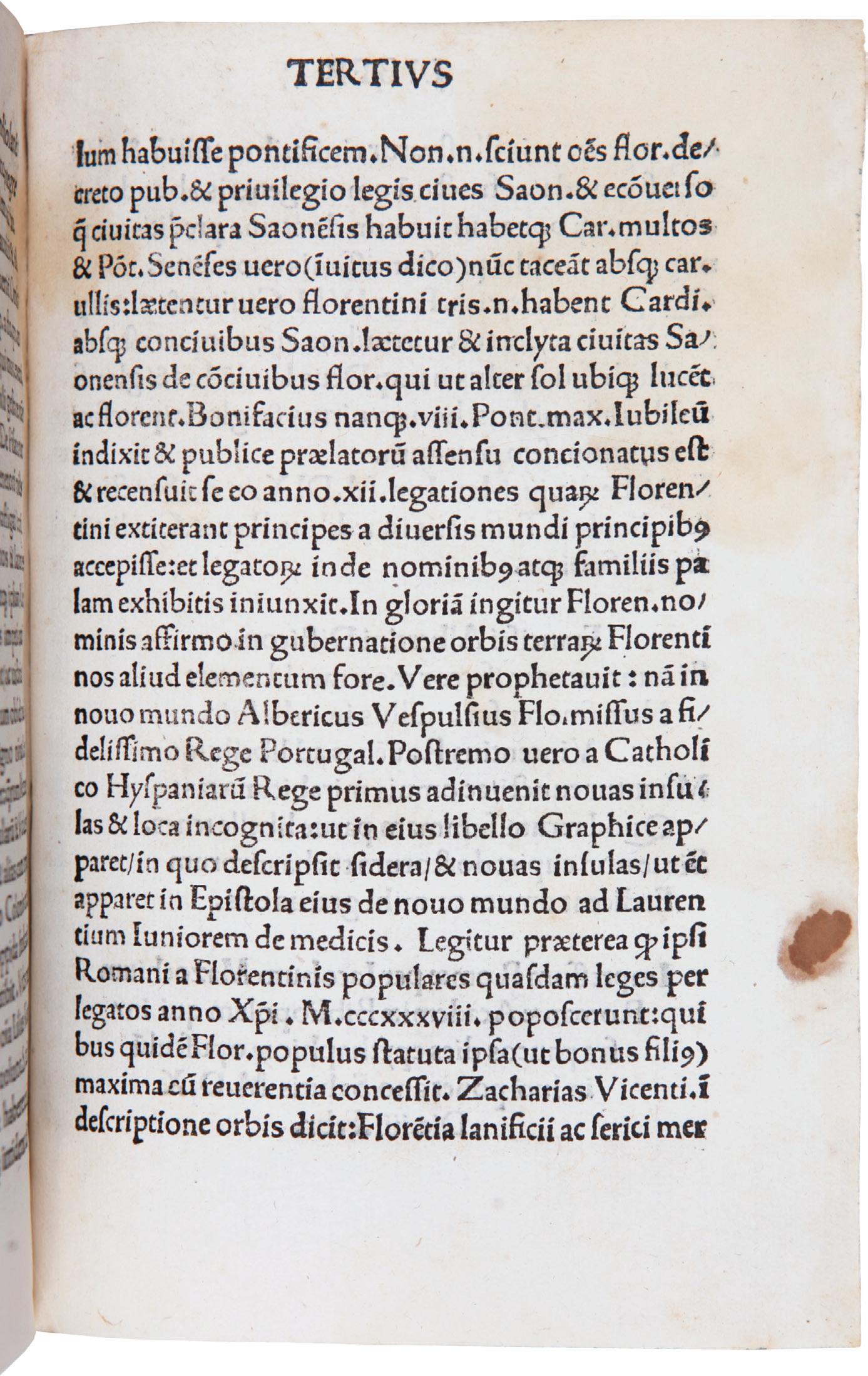

6th climactic region, towards the Antarctic, are situated the extreme part of Africa, recently discovered, the islands of Zanzibar, Java minor and Seula, and the fourth part of the world which, since it was discovered by Amerigo, it is permissible to call ‘Amerigen’, that is, the land of Amerigo or America” (Chapter ix, C3v). The designation was adapted almost immediately by cosmographers (see Borba 931 for its descent).

Throughout the work, Waldseemüller refers to a map and a globe of his design, which are known independently to have been issued in the spring of 1507, thus suggesting that

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 21

the work doubled as a guide to their use. The map survives in a single copy (Shirley #26) discovered in 1901 in the library of Prince Johannes zu Waldburg-Wolfegg in Schloss Wolfegg in Württemberg, Germany, and purchased in 2001 by the Library of Congress. No globe survives, but two sets of uncut gores do (Shirley #27): one at the University of Minnesota (Bell Library), and one other in a private collection.

The work also contains a later printing of Vespucci’s epistolary account of his Four Voyages, first published in Florence between 1505 and 1506. Alberto Magnaghi in his Amerigo Vespucci, studio critico (Rome, 1926) doubted the authenticity of much of the work due to textual inconsistencies, arguing that Vespucci actually made only two voyages: the first with Hojeda in 1499 during which they sailed down the South American coast from the Guianas to latitude 6 degrees south; and the second in 1501 at the expense of the King of Portugal when he followed the Brazilian coast down to 50 Mundus Novus. With his more recent annoDer “Mundus Novus” des Amerigo Vespucci (Vienna, 2002), Robert Wallisch disputes much of Magnaghi’s arguments.

The present work was first published on April 25, 1507, in two discernible editions and a third on August 29 of the same year. An alleged fourth edition also published on August 29 was thought to exist in a single copy, but this was proved to be a composite of the previous three editions and not a true edition (e.g., Church I, p. 57). The present is thus the fourth edition. The first edition is exceedingly rare, known in only two examples. Although subsequent editions are less rare, all are extremely scarce on the market.

The present example is significant for its extra-illustrations, notably an example of the woodcut world map by Jacques Severt (Shirley #179), a north polar projection extending to the equator with the four continents designated in capitals, a reduction of the 1581 map of Guillaume Postel.

A work of fundamental importance for the history of the Americas.

Borba de Moraes p. 932; Church 32; European Americana 509/13; Harrisse (BAV) 60; Sabin 101022; Shirley, Mapping of the World, cf. 26–27; cf. Streeter Sale 4; cf. Streeter, Americana-Beginnings 2.

SOLD

22

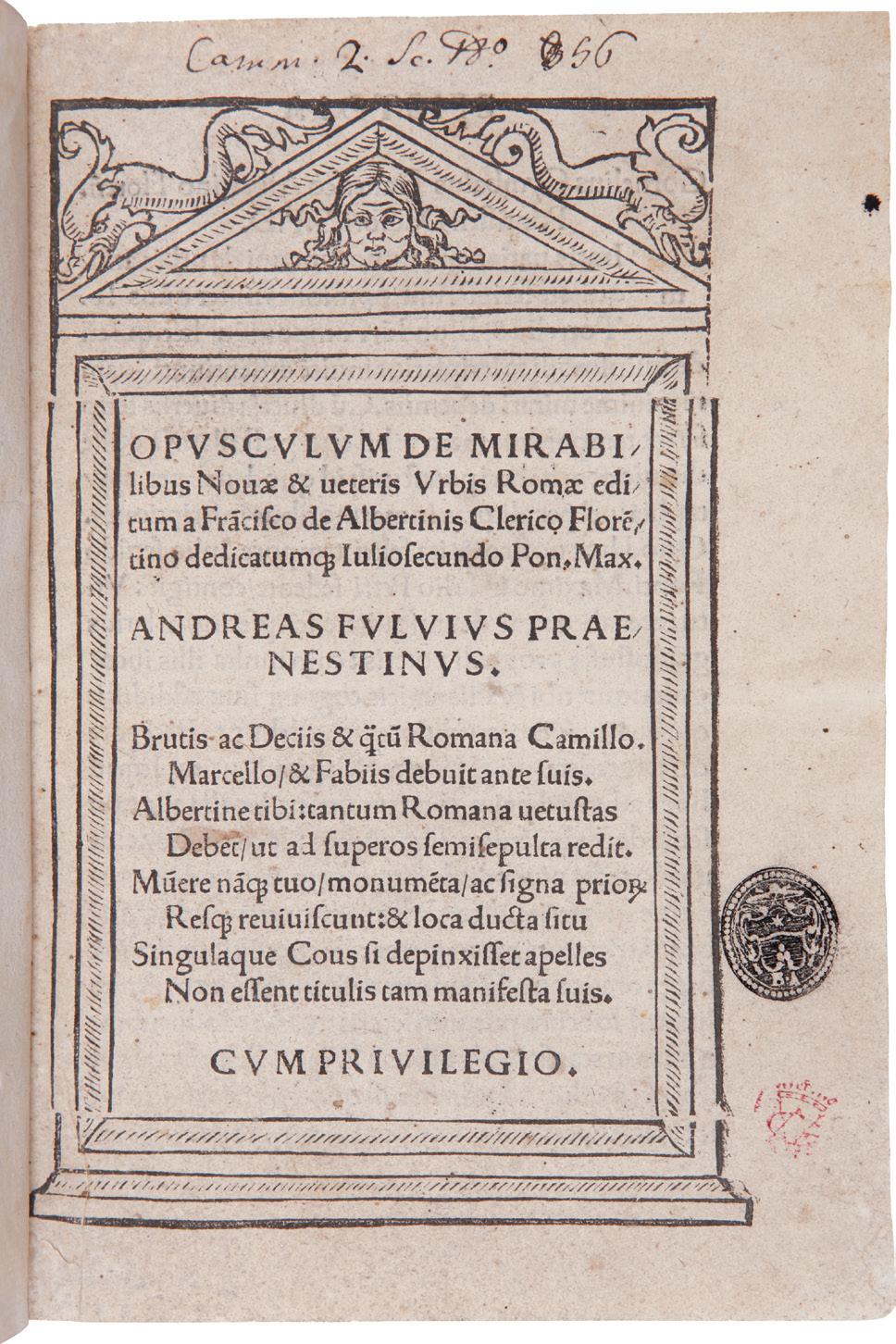

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 23

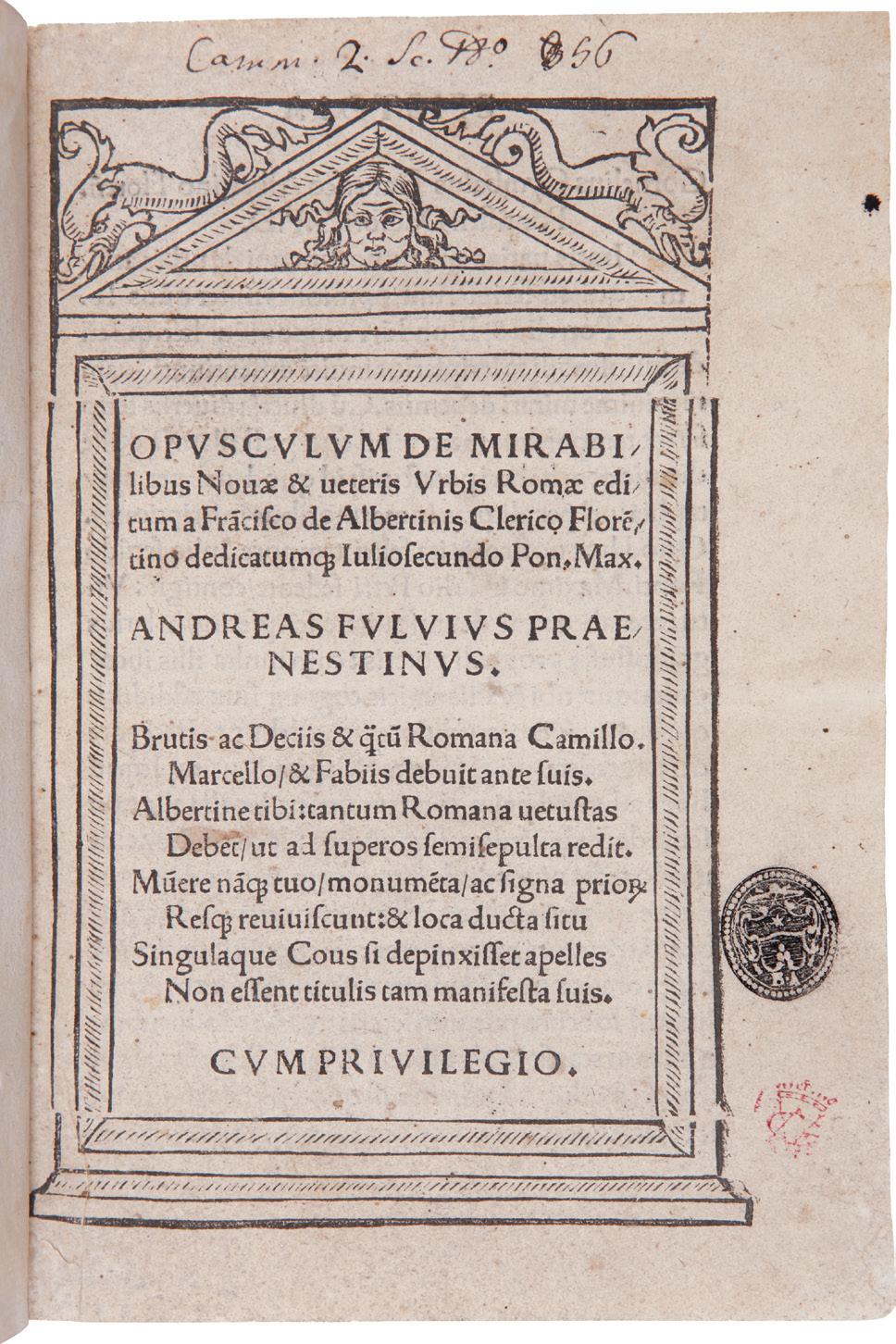

as the first to discover “novas insulas & loca incognita” on behalf of the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs.

The work was compiled for Cardinal Galleotto delle Rovere, nephew of Pope Julius II, who requested that the Florentine humanist, Albertini, write an accurate and up-to-date guide to the city of Rome. This was intended to replace the Mirabilia Romae Urbis, a guidebook first produced in the twelfth century in response to the demand from pilgrims for an historical and artistic itinerary to the city. In responding to the Cardinal’s request, Albertini’s handbook contains descriptions of ancient ruins and later buildings including religious, secular, and pagan sites. The Renaissance guide includes the first printed reference to Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel.

The small black inkstamp on the title page of this copy belongs the prominent Albani family from Urbino, whose ranks included the collector and cardinal Alessandro Albani, as well as Giovanni Francesco Albani, later Pope Clement XI. Clement was a supporter of the Vatican Library, and his abiding interest in antiquity and the preservation of Roman artifacts would have made the present volume a particularly relevant part of his collection. The Bibliotheca Albana was amassed primarily in the eighteenth century, and though much of it was confiscated during the French Revolution, a large portion remained intact until it was sold in the early twentieth century.

European Americana 510/1; Harrisse (BAV) 64; JCB (3) I:50; Sabin 663.

A RARE POLISH AMERICANUM

$9,500

10. STOBNICZA, Johannes de [Jan de Stobnicy]. Introductio in Ptholomei Cosmographia[m] cu[m] longitudinibus et latitudinibus regionum et civitatum celebriorum. Krakow: Florian Ungler, [1512].

Quarto (200 × 140 mm): π A 4 (-A4, cancel) B-C 4 D 6 E-L 4; 46 leaves. Errors in pagination as issued. Full-page woodcut of armillary sphere, half-page woodcut of the quadrant, numerous 5- to 12-line woodcut initials, tables and printed marginalia. Without the two maps, as usual, but with a facsimile inserted. Modern half pigskin over wooden boards, raised bands, brass clasps. Evenly tanned, trimmed close at outer edge with minor loss to shoulder notes.

First edition of a highly important early Americanum, containing references to Vespucci, as well as a description of the isthmus of Panama before Balboa’s “discovery” of the same. The first printed use of the name “America” in Poland, Stobnicza’s work is largely based on Waldseemüller’s Cosmographia of 1507. Indeed, Stobnicza is one of the few cartographers we are certain to have seen the 1507 Waldseemüller world map: “The great Waldseemüller map was not easily circulated, and it is likely that its facts and theories were more quickly disseminated by such earnest gleaners of knowledge as Stobnicza, in his Introductio in Cosmographia” (Yarmolinksy, p. 30).

Stobnicza (ca. 1470–1530?), a specialist in metaphysics, held the chair of cosmography at Kracow and later entered the Franciscan order there. His treatise occupies the first thirteen folios of his Introductio, and it is here that we find his observations

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 24

on the newly discovered lands to the west. “And lest for Ptolemy alone I had labored, I have taken care also to make notes about certain parts of the land unknown to Ptolemy and other older writers, which have come to our knowledge through the travels of Americus, and others,” he writes in his introduction, making good on his promise in chapters III, VII, and IX. On the verso of folio vii we find: “Not only the before-mentioned three parts [of the earth] are now known, but another, a fourth part, has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci, a man of penetrating genius, which part they propose to call Amerigen, or America, the land of Amerigo, after the same Amerigo, its discoverer.” Columbus’s name is notably absent from Stobnicza’s pages, lending currency to the contemporary misconception that Vespucci was the true discoverer of America.

As listed on the title page, Stobnicza’s own commentary is followed by selections from Silvius, Isidore of Seville, Paulus Orosius, and a lengthy description of the Holy Land by Stobnicza’s countryman Friar Anslem, a friend of Copernicus who had made a pilgrimage there in 1507.

The presence of two maps covering the Eastern and Western Hemispheres has been confirmed in just four of the twenty-one known copies of the work, and they are not present here. There remains no consensus on whether the book was issued with the maps, as they were produced by a different printer and their size makes one question whether they belong in the present work. Nevertheless, we know Stobnicza saw the original 1507 world map and so was able to make copies of the two small inset maps. It has been theorized that Stobnicza is likely the person who showed a copy of the 1507 map to Copernicus in Kracow, which provided the source of his commentary in De Revolutionibus.

Two issues of the first edition are noted: with and without a date to the colophon (the present being the latter) and with variations to the setting of the final four leaves. A second edition was published in 1519.

European Americana 512/7; Harrisse (BAV) 69; JCB (3) I:54; Sabin 91866; Yarmolinsky 15–30.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 25

SOLD

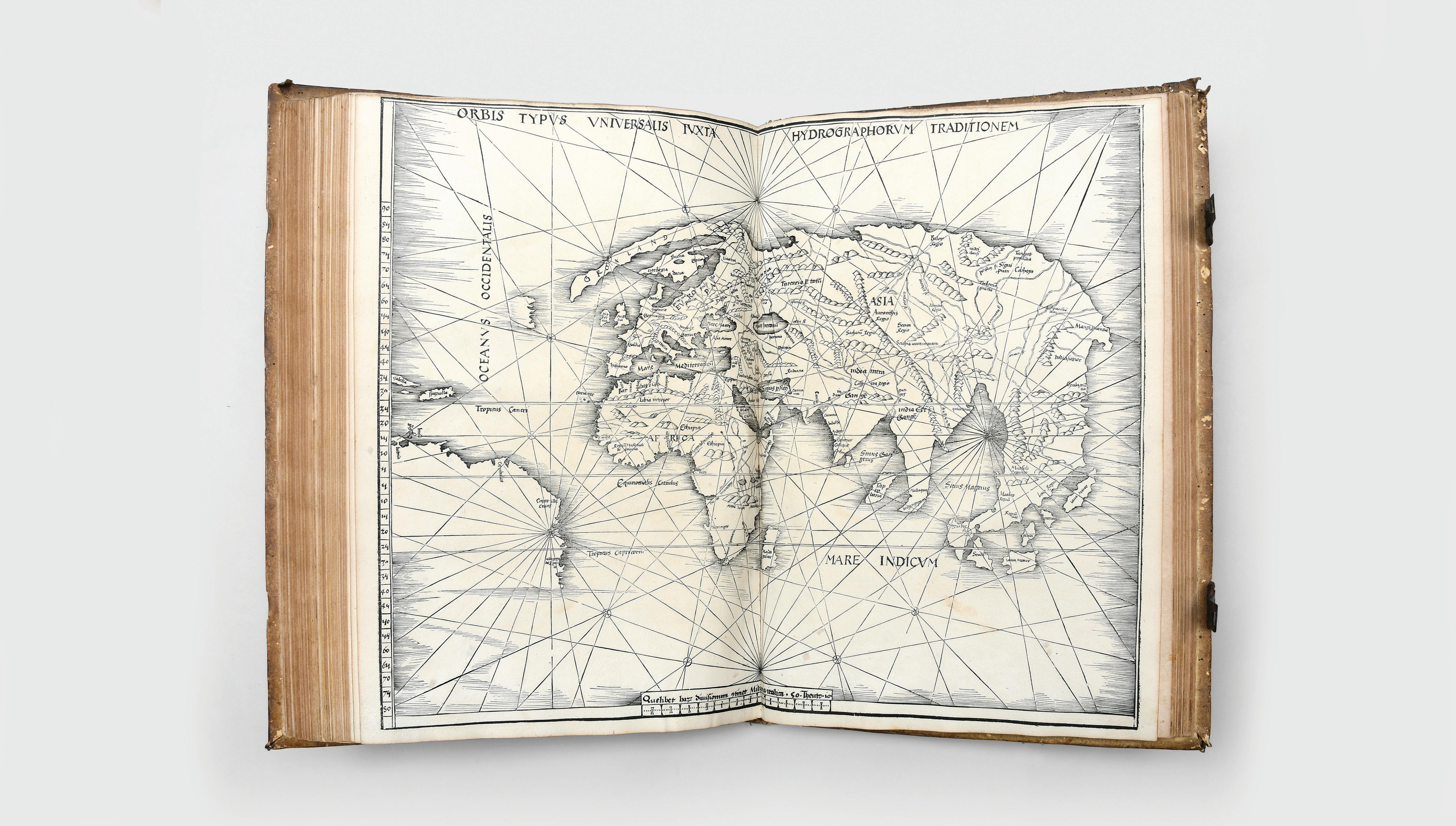

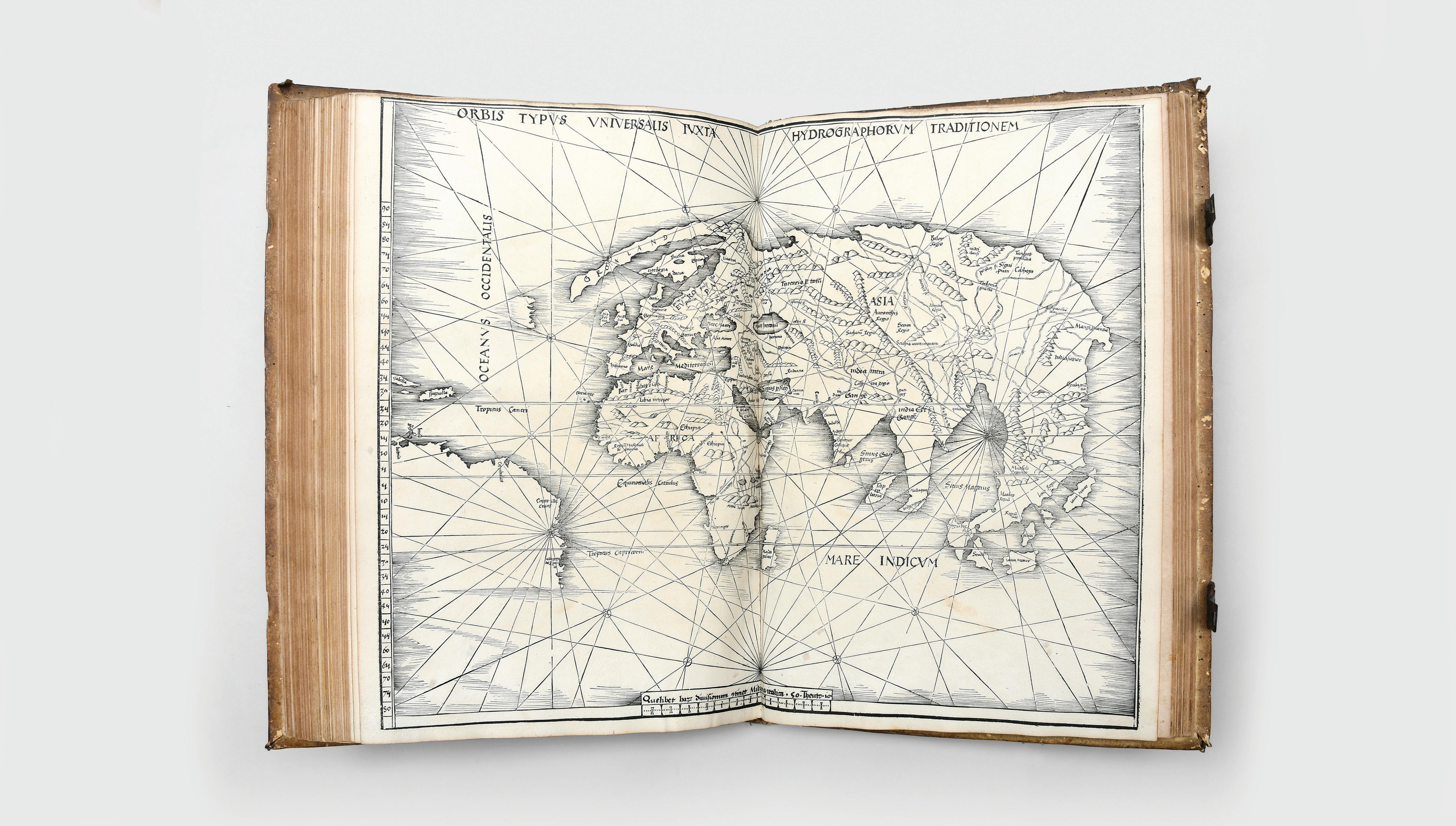

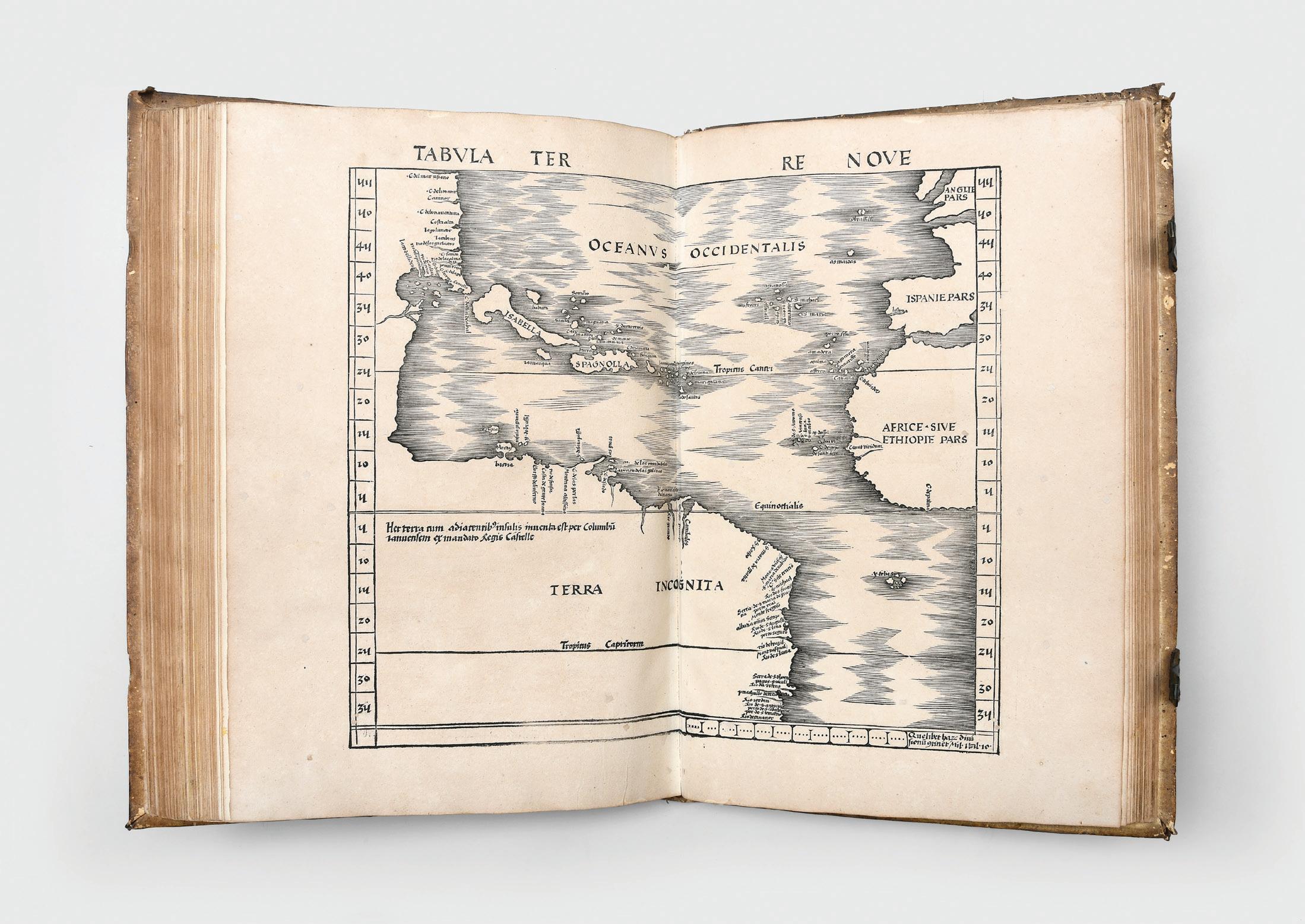

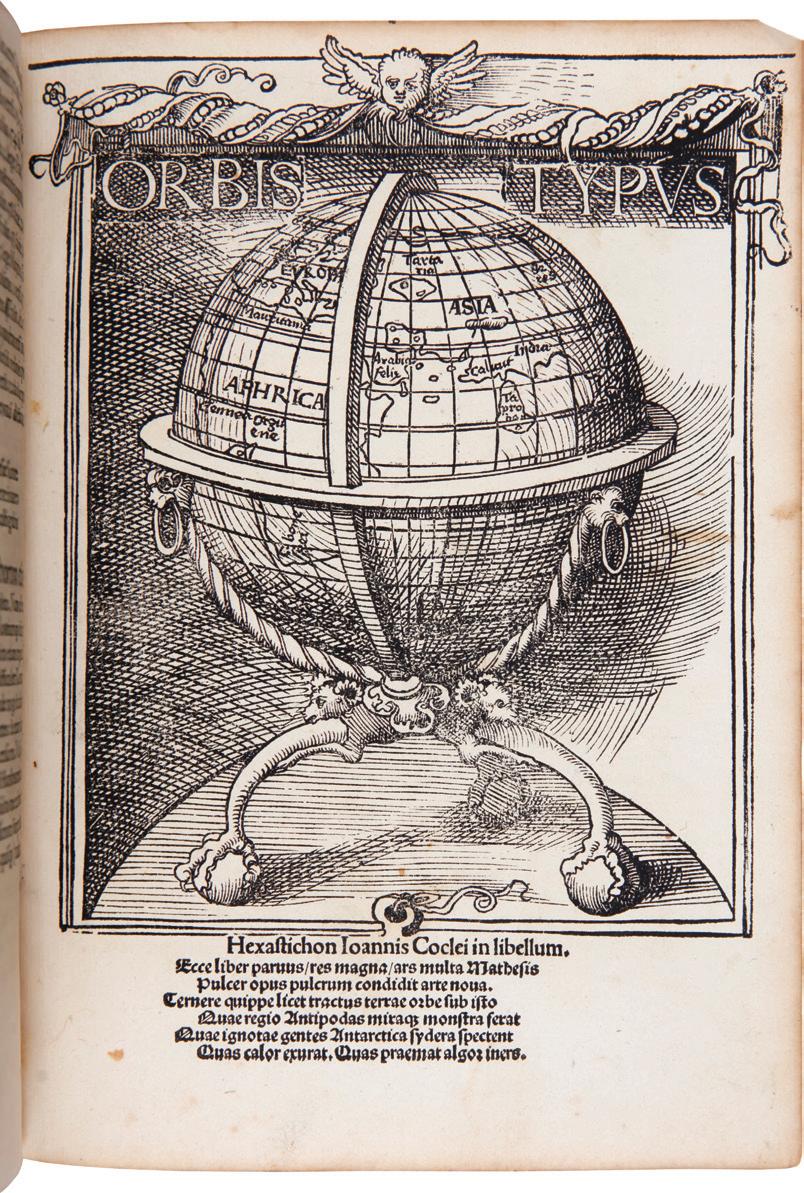

THE FAMED 1513 PTOLEMY: AN EXTRAORDINARY COPY IN A CONTEMPORARY BINDING OF THE FIRST ATLAS TO CONTAIN A MAP OF AMERICA

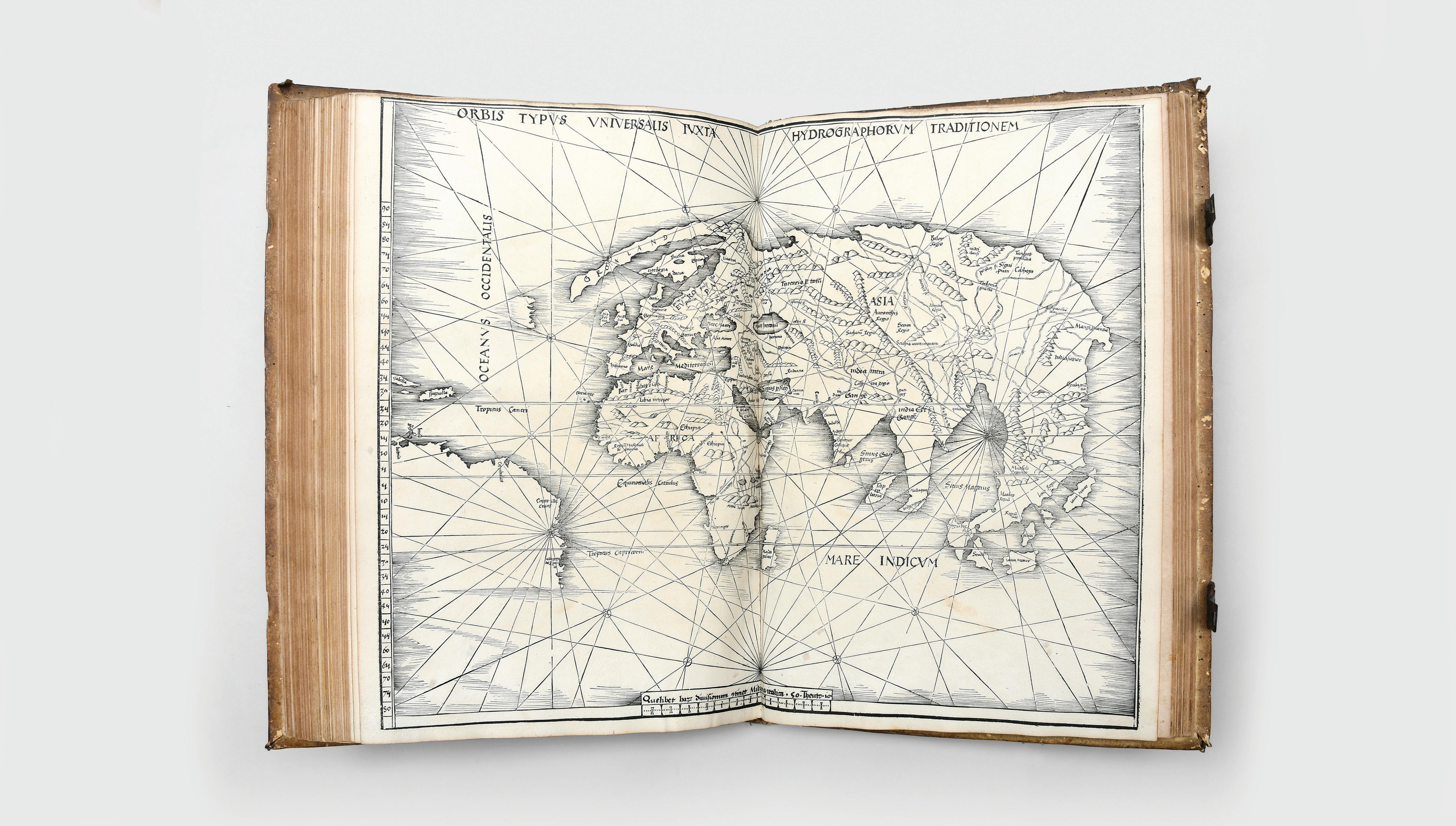

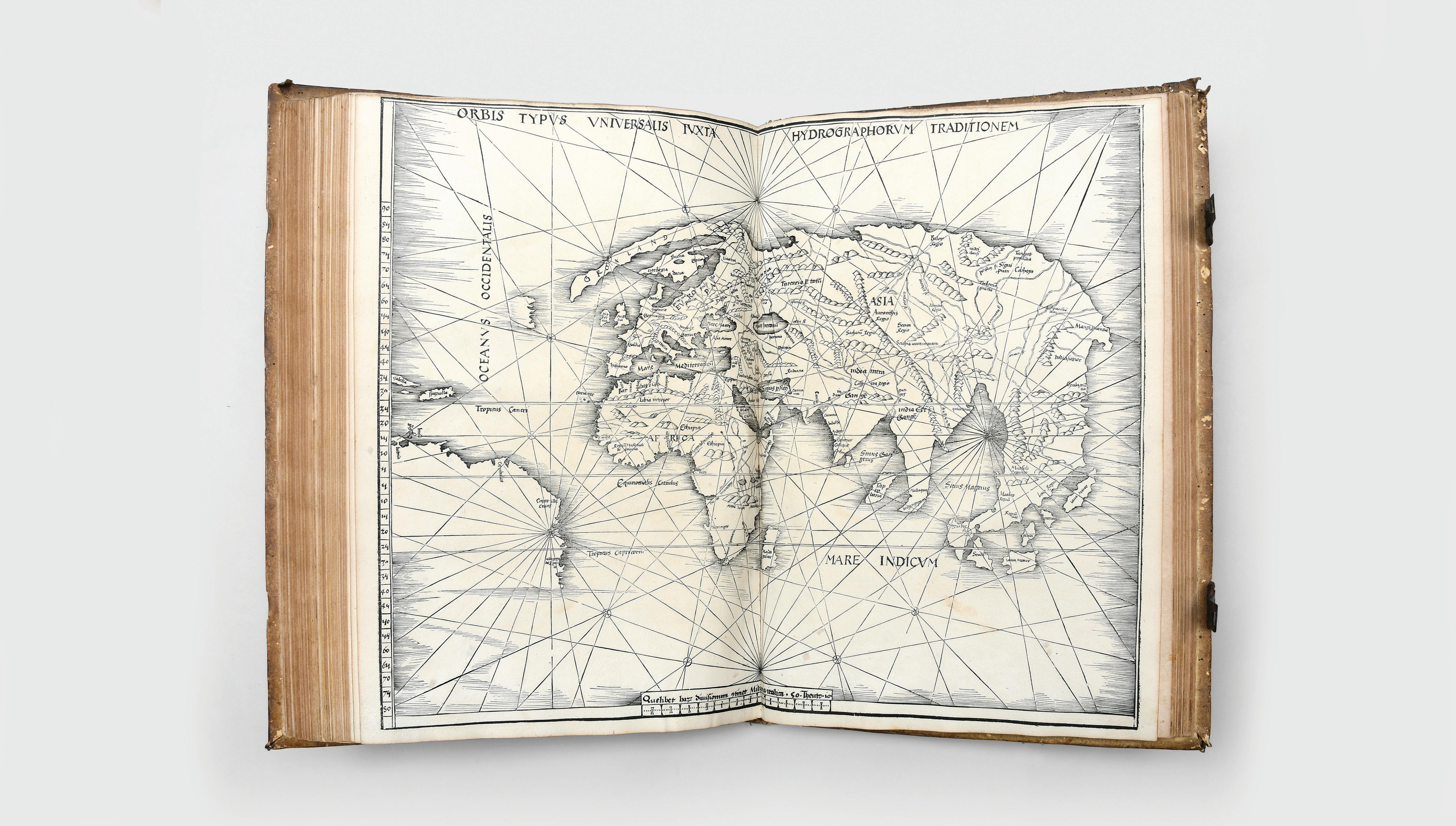

11. PTOLEMAEUS, Claudius; and Martin Waldseemüller, cartographer Geographie opus novissima traductione e Greco cum archetypis castigatissime pressum: ceteris ante lucubratorum multo prestantius. Strassburg: Johannes Schott, 1513.

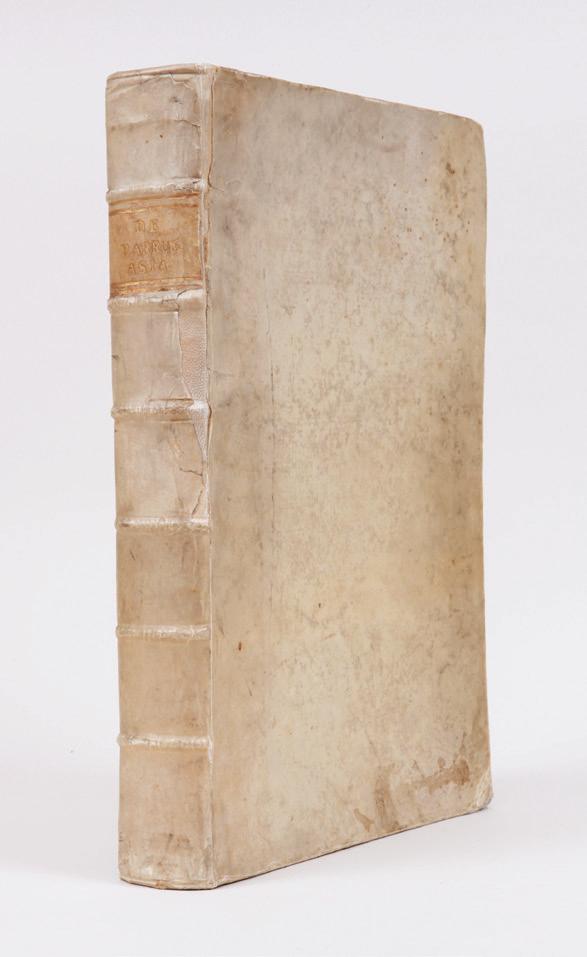

Folio (455 × 300 mm): A 2 B-L6 M4 N6; 26 double-page maps, 1 single page map; 19 double-page maps, 1 single page (Lorraine) printed in three colors; π1 (index to modern maps) a6 b4c6 (including terminal blank); 181 leaves in total, complete. Contemporary blindstamped pigskin over bevelled wooden boards, raised bands on spine, with original catches and clasps intact. Old shelf-label on spine. Binding rubbed in places and wormed. Scattered minor worming, mostly marginal, some of it plugged, but sometimes affecting partial letter of text, not affecting maps; even toning and minor staining (marginal) to scattered leaves. Some discoloration from humidity in upper margin of a few leaves. Generally an unusually broad-margined and fresh copy, most likely in its original binding (maps secured by vellum tabs), with the woodcut maps in excellent strikes.

A fine copy in a contemporary pigskin binding of “the most important of all the Ptolemy editions; its supplement of ‘new’ maps marked the beginning of modern map-making. The new maps, based on contemporary observations, were published alongside the long-authoritative Ptolemaic models whose deficiencies were clearly recognized” (Streeter). The work contains the first map of America to appear in an atlas and, among printed books, is preceded only by the map that should accompany the 1511 Peter Martyr (of which Burden was only able to locate ten copies worldwide).

This masterful atlas is one of the most important cartographical works ever published. The first part of this atlas consists of twenty-seven Ptolemaic maps, taken from the 1482 Ulm Ptolemy, or perhaps the manuscript atlas of Nicolaus Germanus upon which the Ulm Ptolemy was based. Work on the twenty maps in the Supplement began around the year 1505 by geographers Martin Waldseemüller and Mathias Ringmann, and was partially funded by Duke Rene of Lorraine. The accompanying text was completed a bit later, and in 1508 all the materials for the atlas passed into the hands of two Strassburg citizens, Jacobus Eszler and Georgius Ubelin, at whose cost the work was completed in 1513.

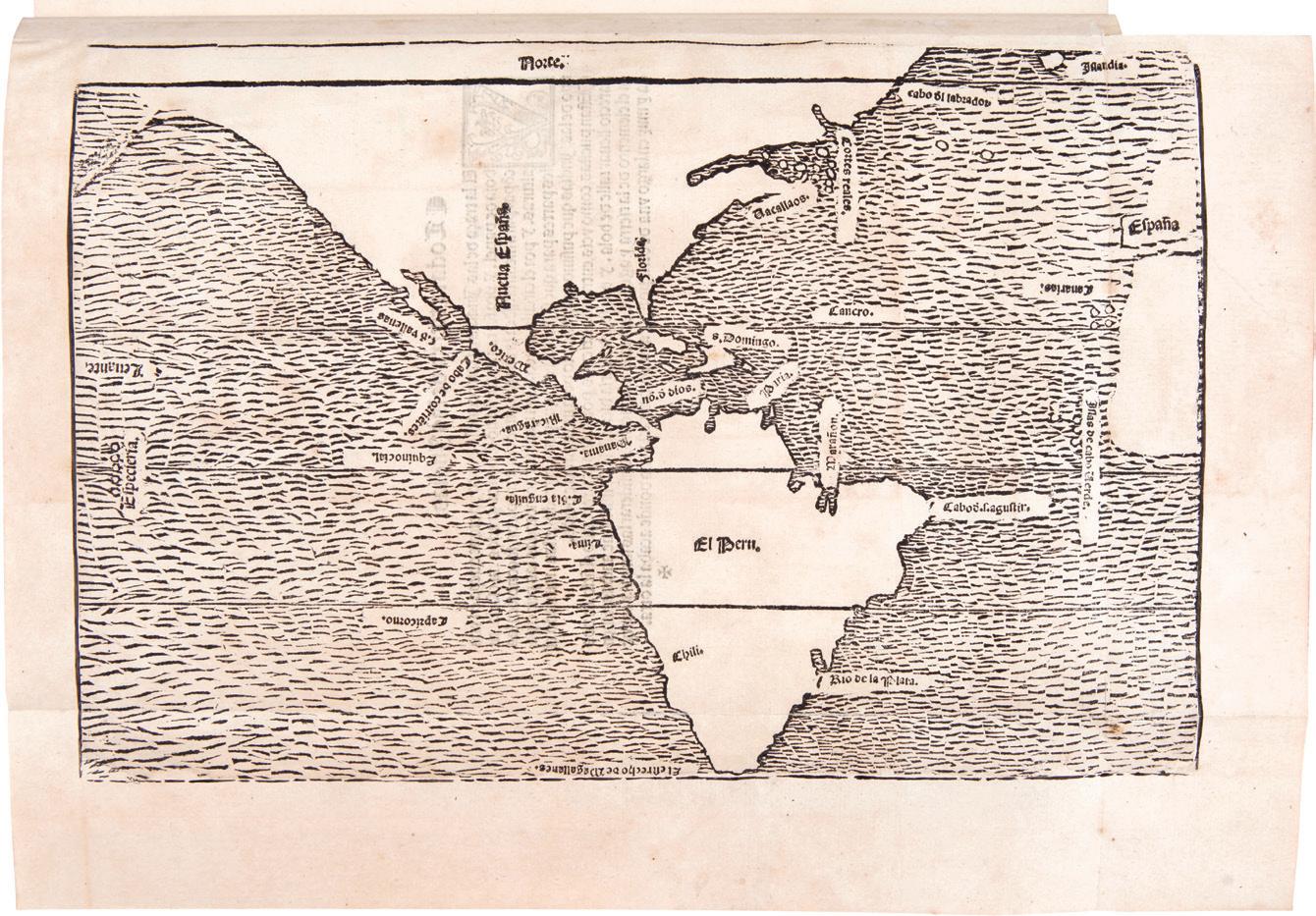

The atlas is a notable Americanum as it contains the map of the world known as “the Admiral’s map,” variously attributed to either Columbus or, rather less probably, Vespucci. This map, “Orbis Typus Universalis,” first appears in this edition, and depicts the outline of northeastern South America, with five names along that coast, and the islands Isabella and Spagnolla, and another fragmentary coast, as well as an outline of Greenland. Two other maps are also of American interest. “Tabula Terre Nova” is one of the earliest printed maps devoted entirely to the New World and depicts the coast of America in a continuous line from the northern latitude of 55 degrees; to Rio de Cananor at the southern latitude of 35 degrees, with about sixty places named. It was not until 1534 that another large-scale map of the Americas was published, by Giovanni Battista Ramusio. A third map, “Tabula Moderna Norbegie et Gottie,” shows “Engronelandt” and “Engronelad.”

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 27

Among other notable features, the map of Lorraine is the earliest attempt at color printing on a map, and the map of Switzerland is the first printed map of that nation. For comprehensiveness and the geographical accuracy of its contents, especially for the dissemination of the most recent and epochal transatlantic discoveries, this was the most important atlas of the sixteenth century until the publication of Ortelius in 1570.

“The merit of this edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia is great, for it not only corrects Angelo’s translation by means of a Greek manuscript until then unknown, but it contains 20 new maps, among which the reader will notice the first, bearing the title of: Orbis Typis Universalis iuxta Hydrographorem Traditionem and presenting on the left of the reader a promontory, with 5 inscriptions, and 2 islands (viz. Isabella and Spagnolla); and the second map which is headed Tabula Terre Nove. The latter is very full, considering the times, as it shows a prolongation of the coast from a certain Rio de cananor to a cape del mar usiano. There are not less than 60 names along the coast, besides the inscription afterwards so frequently reprinted: hec terra adiacentib(us) insulis invent a est per Columbum ianuensem ex mandata Regis Castelle. This inscription is on the section which corresponds to what we now call Yucatan, and is followed by the words terra incognita

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 30

“These two maps acquire a certain importance from the following lines, which we extract from the preface on the verso of the second title-page: ‘Charta autem Marina quam Hydrographiam vocant. per admiralem quondam serenissimi Portugalie regis Ferdinandi ceteros denique lustratores verissimis pagrationibus lustrata.’ (‘But the Charta Marina, which they call the Hydrographia, prepared from the most authentic voyages [made] by an Admiral formerly of the . . . King of Portugal Manuel, but afterwards of the . . . King of Castille Ferdinand, and by other later explorers, was very liberally given to be engraved.’) This passage has doubtless prompted the opinion that the first of the two maps above described had been depicted by Columbus himself” (Harrisse). Commentators continue to debate the precise meaning of this awkward Latin sentence, though the map utilized as a source has been positively identified as the large chart by Nicolo di Caveri (BnF, reproduced in Nebenzahl 1990, 41–430); this links it to Columbus rather than Vespucci (see Karrow, p. 580).

The participation and principal responsibility for the drawing of the maps are attributed to Martin Waldseemüller, although his name appears nowhere in the atlas. Waldseemüller was the center of a group of geographers who, notwithstanding their comparative isolation in the middle of the Vosges, kept abreast of the most recent geographical explorations of the Spanish and the Portuguese and other geographical evidence housed in the libraries of Basel and Strassburg. His Cosmographiae introductio (1507) is regarded as the book which named America. In recognition of the present atlas and the two separately issued maps he produced, Waldseemüller is called by Karrow “probably the most important cartographer of the early sixteenth century.” A condensed sketch of the present work’s somewhat complicated publishing history can be found in Karrow, Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and their Maps, pp. 577–78, itself a summary of Skelton’s introduction to the 1966 facsimile edition.

It is highly unusual to find the present work in a contemporary binding and in generally fine internal condition: atlases typically saw a lot of use when employed as works of reference and their condition usually reflects this; early atlases were identified as collectibles as early as the eighteenth century and were frequently rebound. A copy as it was issued in the sixteenth century, in a simple binding of pigskin over boards—most likely the original binding judging from the size of the copy and the vellum tabs which secure the maps—is now distinctly uncommon.

A handsome copy in contemporary binding of a monumental and important work, containing critical New World information, derived from the latest voyages of exploration.

Bell P562; European Americana 513/6; Harrisse (BAV) 74; JCB (3) I:57–58; Nordenskiöld p. 19, plates 35 & 36; Phillips Atlases 359; Sabin 66478; Shirley, British Isles 10; Shirley, Mapping of the World 34; Streeter Sale 6; World Encompassed 56. Stevens, Ptolemy’s Geography (1908), p. 44. See R. A. Skelton, “Introduction to Claudius Ptolemaeus Geographia Strasburg 1513” in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, second series, volume IV (1966) on the publishing history and the participation of Waldseemüller.

$1,250,000

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 31

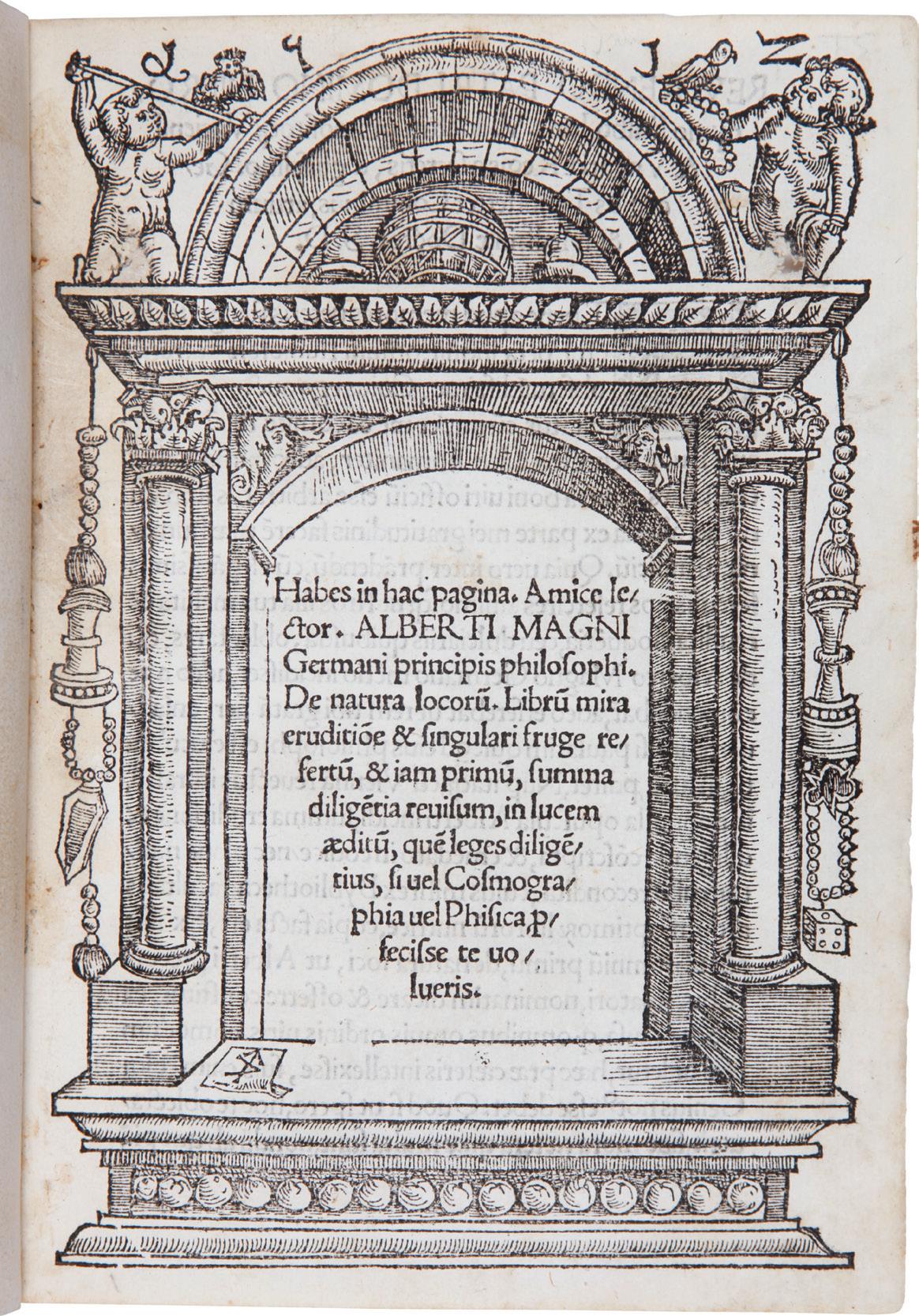

ANTICIPATING THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

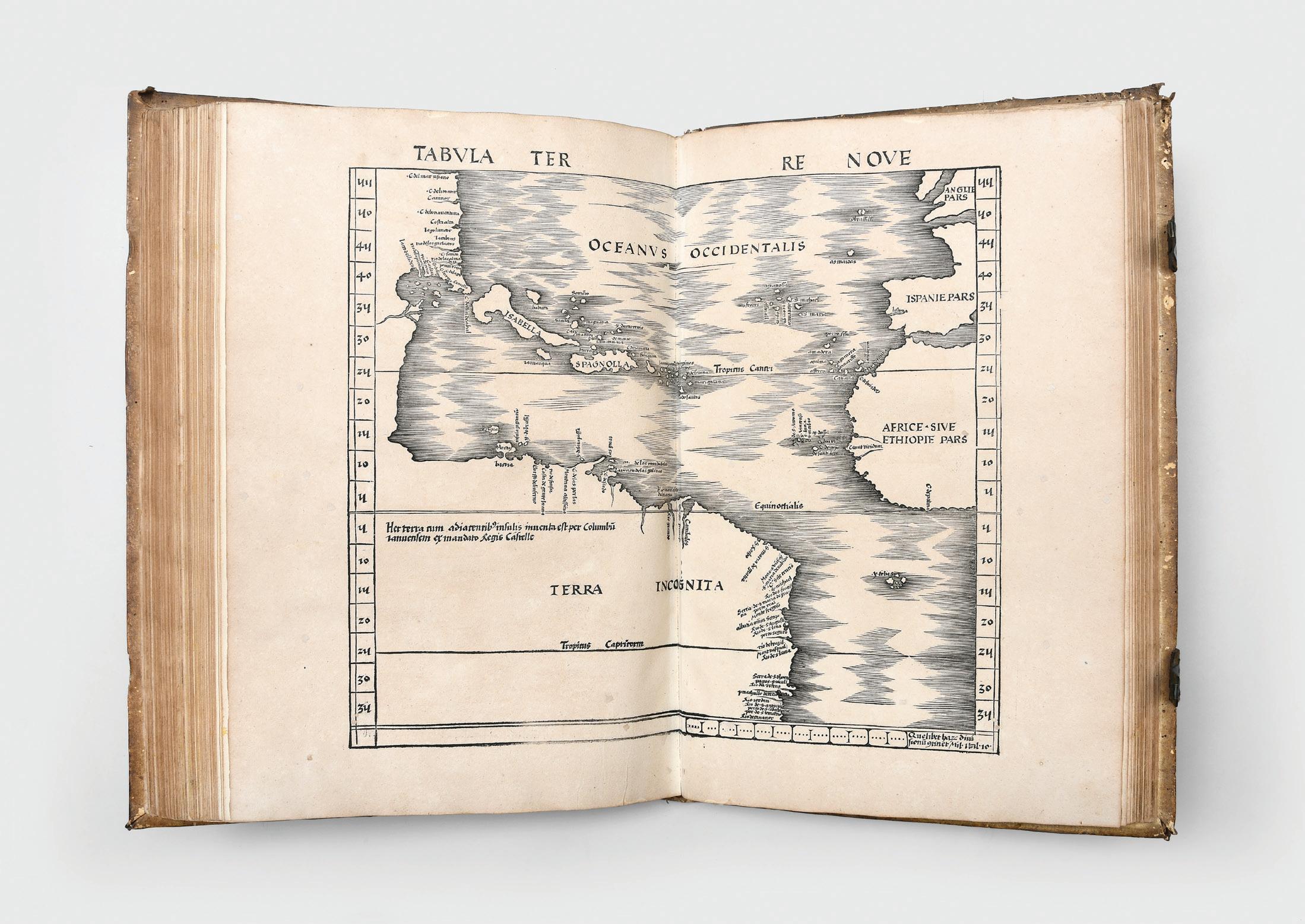

12. ALBERTUS MAGNUS. Habes in hac pagina, amice lector . . . De natura locarum. Vienna: by Hieronymus Vietor and Johann Singriener, for Leonhard and Lucas Alantsee, 1514.

Quarto (200 × 140 mm): a6 b–l 4 m 6; [52] leaves. One woodcut initial, spaces for other initials, with guide letters; title within a woodcut architectural border, dated 1512, woodcut coat-of-arms on last leaf. Late nineteenth-century blindstamped calf, raised bands. A bit soiled and rubbed. Very small paper flaw in title leaf grazing border without touching text, a few instances of early marginalia and underlining.

First edition of Albertus Magnus’s treatise De Natura Loci (”On the Nature of Place”), originally written between 1248 and 1252, important not only as the first Western work to consider geography as a separate discipline but as the first attempt at a comparative geography. Albertus Magnus (ca. 1200–1280), a German Dominican friar, philosopher and scientist, was among the most accomplished scholars of the Middle Ages, particularly noted for his contributions to the natural sciences. The present work was edited in 1514 by Georg Tannstetter (1482–1535), also called Georgius Collimitius, a humanist teaching at the University of Vienna. He was a medical doctor, mathematician, astronomer, cartographer, and the personal physician of the emperors Maximilian I and Ferdinand I.

In the work, Albertus Magnus describes how geographic factors, such as the height above sea level, proximity to the sea, mountains and vegetation, influence climate. He also considers life at the equator and the poles, assuming that the poles would be uninhabitable with half the year being day and half night. In chapter VII, entitled: “As to whether the fourth part of the world is inhabitable, which stretches from beneath the Equinoctial pole to the Austral pole,” Albertus wrote that the southern hemisphere would be habitable. This passage is marked by Tannstetter on leaf D4 recto with a marginal note, apparently inserted with movable type after the book had been printed, stating that the author “concludes that beyond the ecliptic, in the 50th degree, that region which Vespucci in his voyages in former years discovered and describes, was habitable,” i.e., that Albertus Magnus had anticipated the discovery of America in the mid-thirteenth century.

European Americana 514/1; Harrisse (BAV) 76; JCB (3) I:58; Sabin 671.

$15,000

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 32

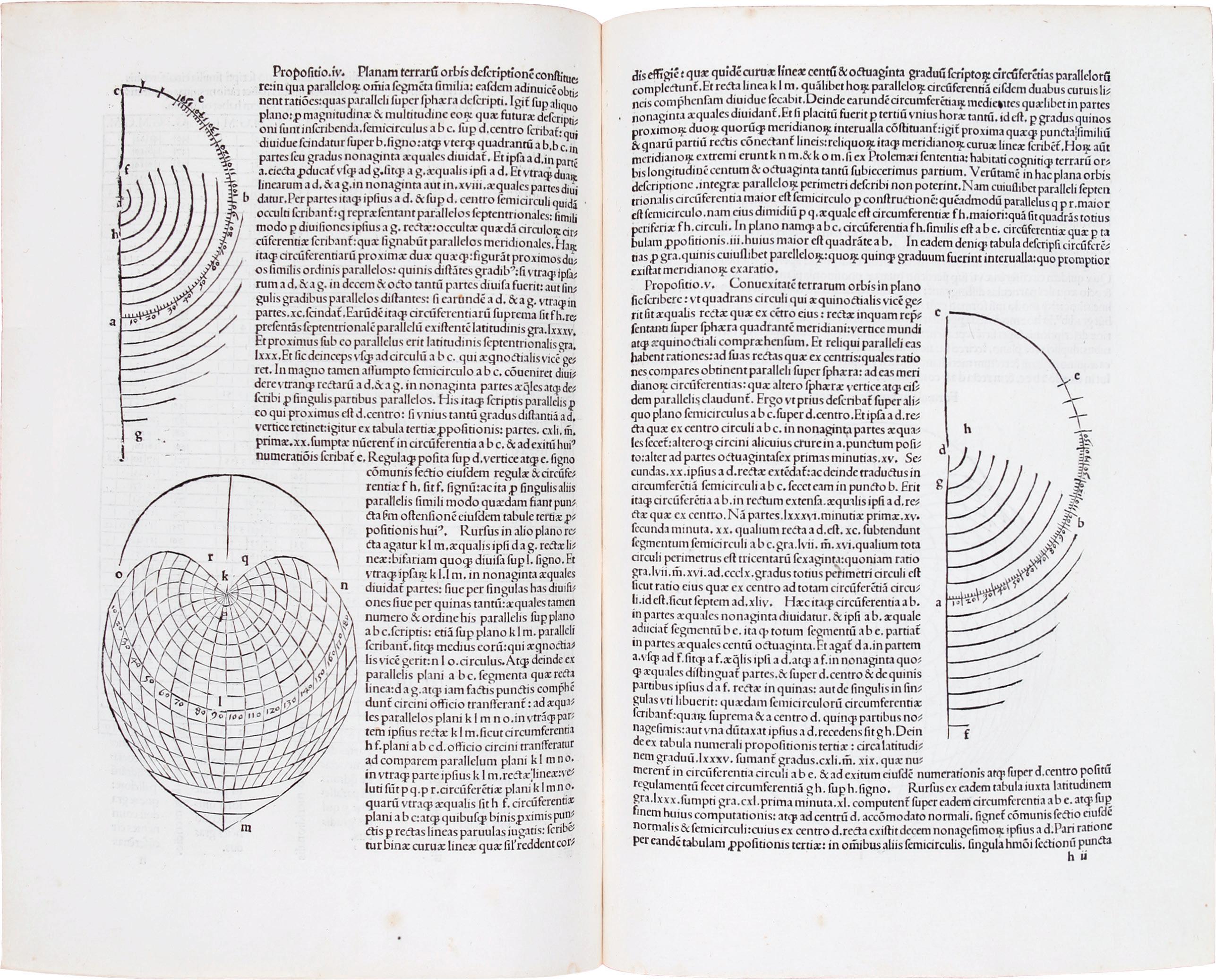

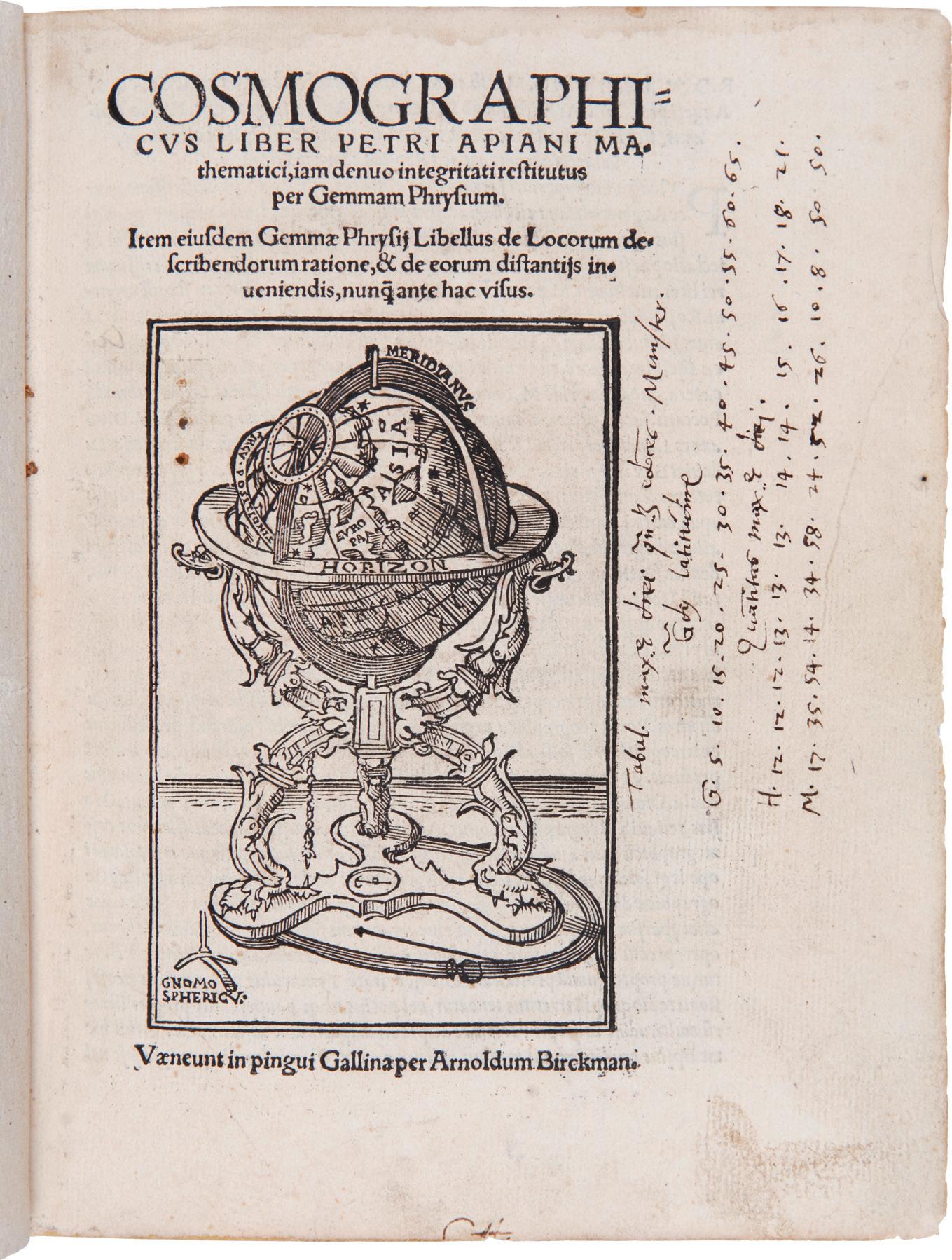

THE FIRST SEPARATELY PUBLISHED BOOK DEVOTED TO MAPMAKING

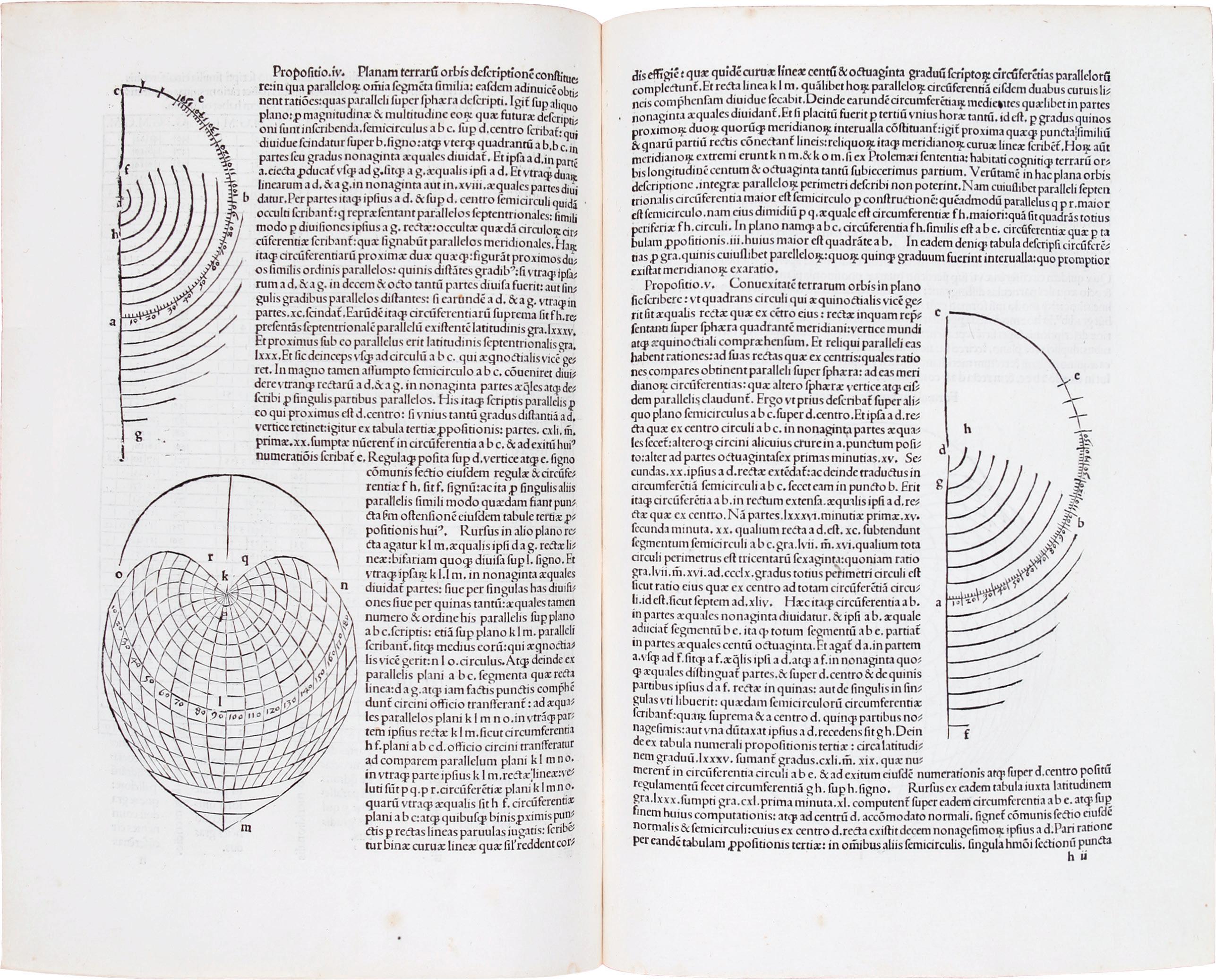

13. PTOLEMAEUS, Claudius; and Johannes Werner. In hoc opere co[n] tinentur. Nova translatio primi libri geographiae Cl. Ptolomaei . . . in eiundem primum librum . . . annotationes. Nuremberg: Johann Stuchs, 1514.

Folio (302 × 200 mm): a–c6 d8 e–h 6 i8 k 6 l 4; [68] leaves. With 75 woodcut diagrams, 3 of them full-page. Later elaborately blindstamped pigskin with metal hinges, raised bands and gilt spine la bel, marbled endpapers, red stained edges. Clasps lacking, minor worming to spine. Light scattered foxing and staining but otherwise remarkably clean internally. Occasional early manuscript annotations throughout. Provenance: 19th-century (German?) armorial bookplate on front pastedown.

One of the most famous and influential works in the fields of modern cartography and mathematical geography, Werner’s work includes the first publication of several no table map projections and the first discus sion and illustrations of using a cross staff for determining longitude. “For the history of geographical projections, the Renaissance is a time of extraordinary wealth of new in ventions. A great number of new methods of projecting developed rapidly . . . The cause of this phenomenon must be sought in the universal interest in the great discover ies. For the first time in history, attention was directed to the whole earth and at the same time to the necessity of finding a solution for projecting the surface of the globe upon a plane . . . As the Portuguese penetrated farther into the south ern hemisphere and the New World was discovered, the need for representation of the spherical shape of the earth on a plane made itself felt increasingly” (Jo hannes Keuning, “The History of Geographical Map Projections until 1600”, in Imago Mundi, vol. 12, [1955]).

Johannes Werner was an astronomer and mathematician of note in Nuremberg, as well as a parish priest. This work, his most famous, includes the first published direct translation of any part of Ptolemy’s Geographiae from the original Greek. However, its greater importance lies in Werner’s additions. Working with access to the notes of the monumental astronomer Regiomontanus, he supplements his translation with copious mathematical annotations and corrections, as well as with essays entirely of his own. Among these is a discussion of four different map projections, including stereographic projections and his eponymous Werner projection, which would influence cartographers for the next two and a half centuries.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 33

His additions are also notable for describing the concept of the lunar distance method for determining longitude, a method first suggested by Vespucci, with the earliest printed illustrations and instructions for creating and using an instrument for that purpose known as the cross (or Jacob’s) staff, which became the primary method for Portuguese and other explorers well into the nineteenth century. The book also features the first printed description and illustration of the meteoroscope, by way of posthumously publishing one of Regiomontanus’s letters on the subject. The amplification and republication of Werner’s theories by Peter Apian in the succeeding decades, including his projections and use of the cross staff, ensured the enduring influence of this work on navigation and world exploration.

The work is a major landmark in the history of mathematical geography and cartography and an Americanum of note.

European Americana 514/11; JCB (3) I:60–61; Sabin 66479; VD16, P5208. DSB XVI, pp. 272–9. Henry Stevens, Ptolemy’s Geography (London: 1908), p. 49.

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 34

SOLD

EARLY PRAISE OF COLUMBUS

14. CATANEO, Giovanni Maria. Genua. Rome: J. Mazochius, 1514.

Quarto (210 × 145 mm): a –c 4; [12] leaves, including terminal blank. Title within an ornamental woodcut border, woodcut initials. Nineteenth-century half vellum and paper-covered boards. Some soiling to boards. Toning throughout, some dampstaining extending from the lower margin, minor abrasion to lower gutter of title and one other area above, wormtrack in lower blank margin without loss. Contemporary manuscript annotation to title (see below).

The elegiac poem in praise of the city of Genoa, consisting of 446 lines of hexameter, touches on a wide range of the city’s features, including its topography, commercial and industrial life, monuments, customs, and people—notably Christopher Columbus, one of Genoa’s most eminent natives, who gets a special mention for his character, virtue, and world-changing discoveries, on both sides of leaf C2

At this early date, such popular mentions of Columbus were rare and would remain so for most of the rest of the century. Until the end of the sixteenth century, the great explorer’s discoveries passed relatively unnoticed in popular literature, largely eclipsed by Vespucci.

A contemporary manuscript note on the title page appears to be in the hand of someone close to the author, perhaps a friend, who saw the poem before publication. The inscription, added after Cataneo’s name, reads: “quam priusquam imprimeret mihi Romae ostendit et perlegit et iudicio nostro cuicumque.” (“[Giovanni Maria Cataneo] showed this to me before it was printed and read/examined it carefully (taking into consideration) my own opinion.”)

European Americana 514/3; Harrisse (BAV) 75; Sabin 11494.

$8,500

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 35

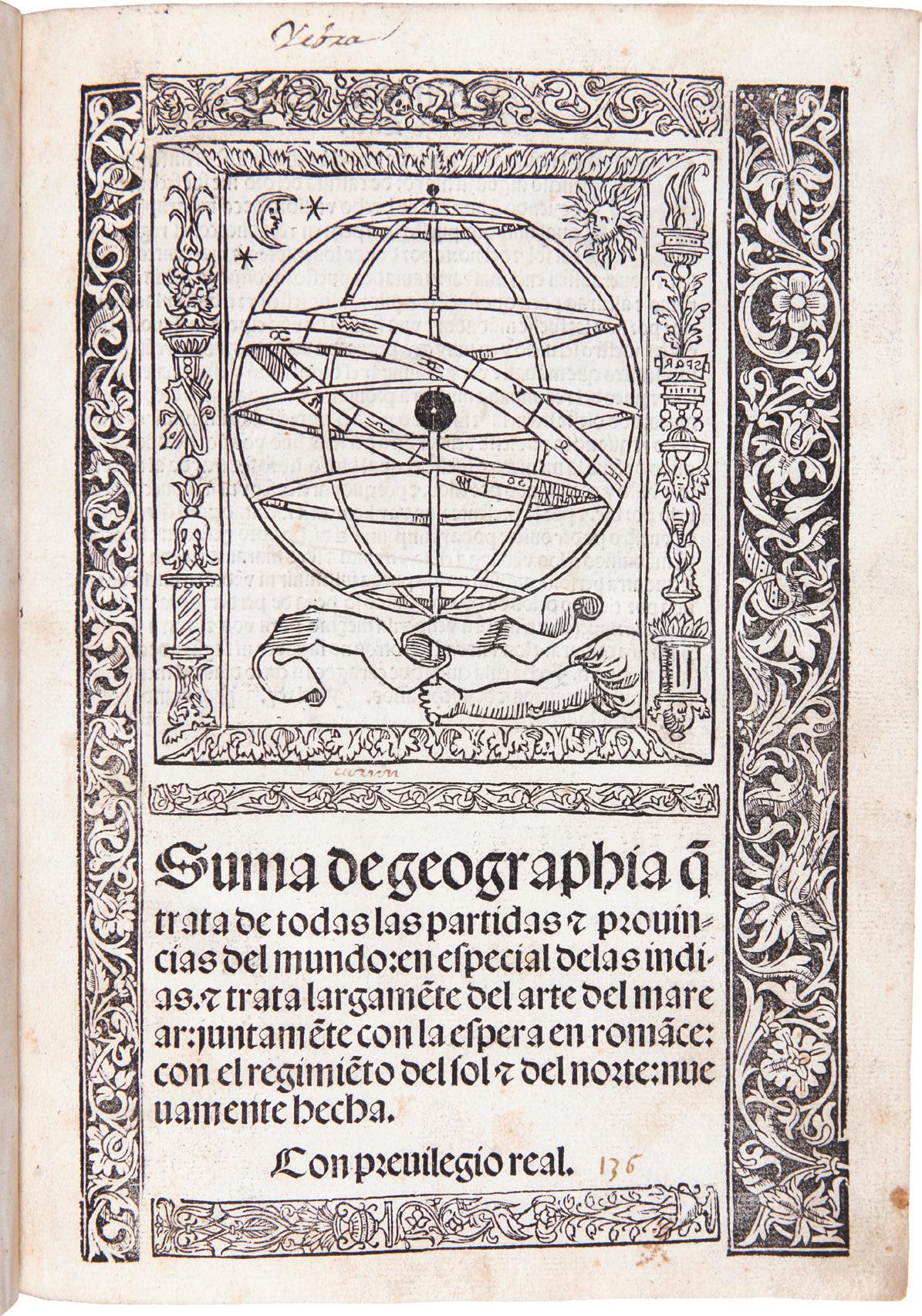

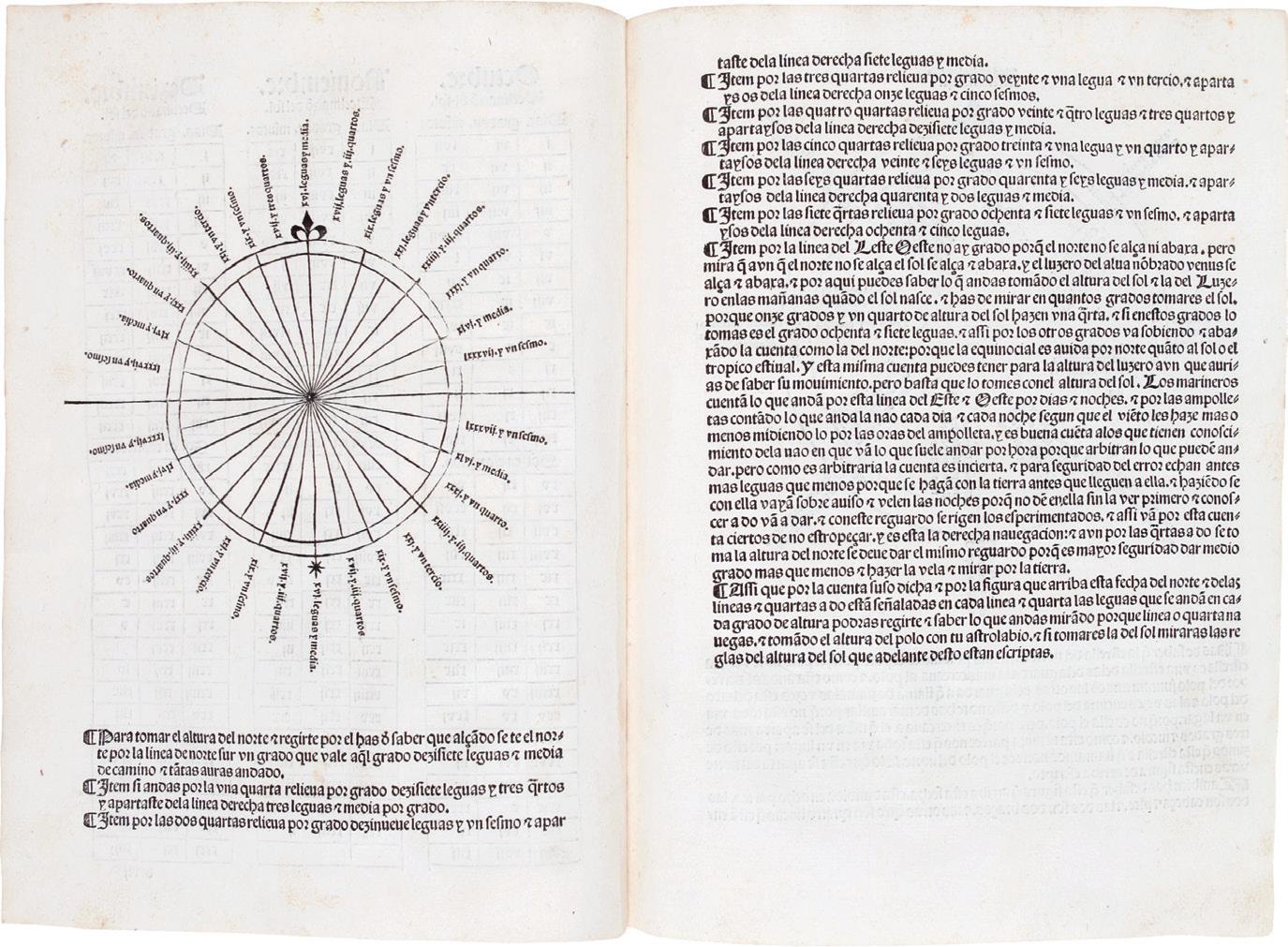

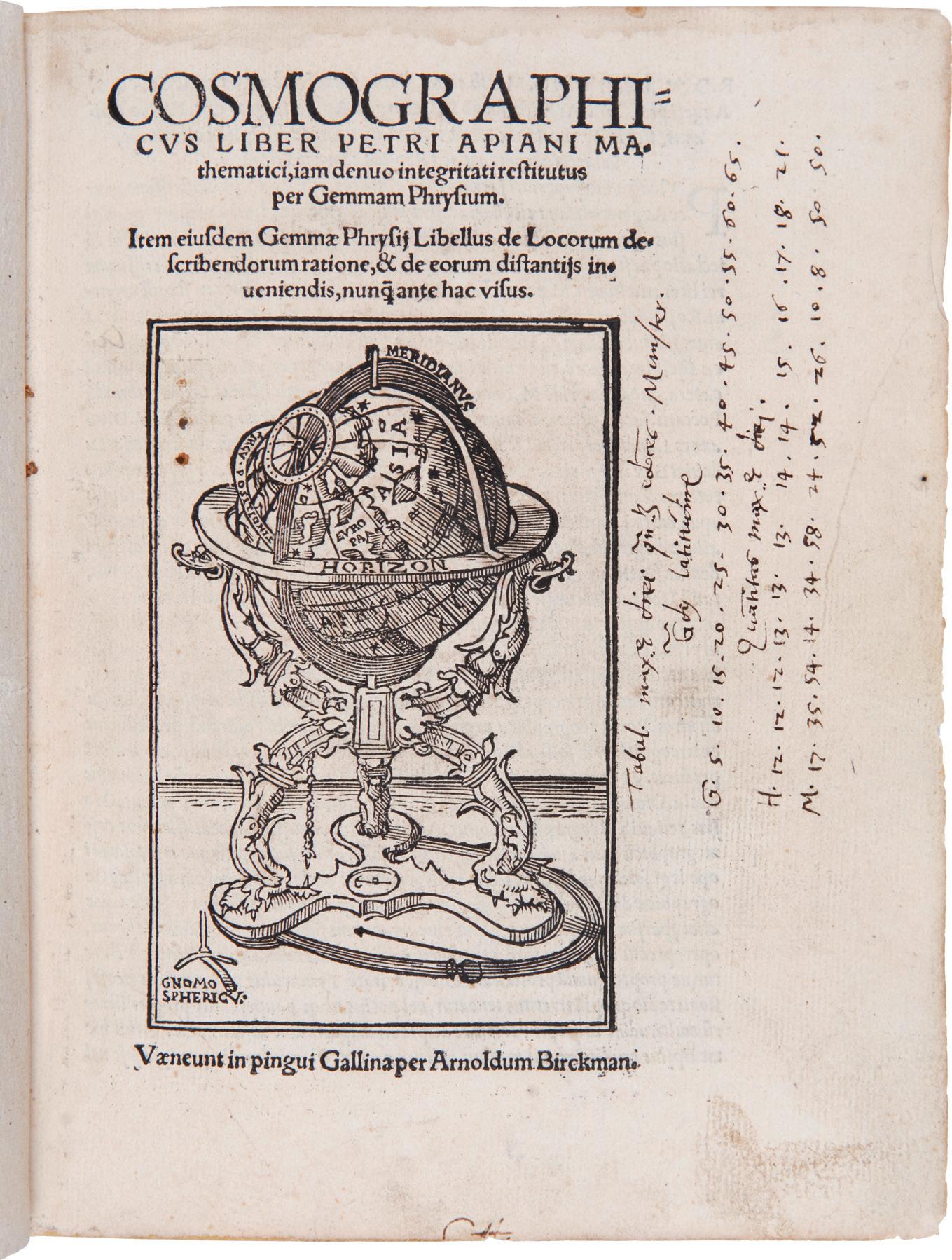

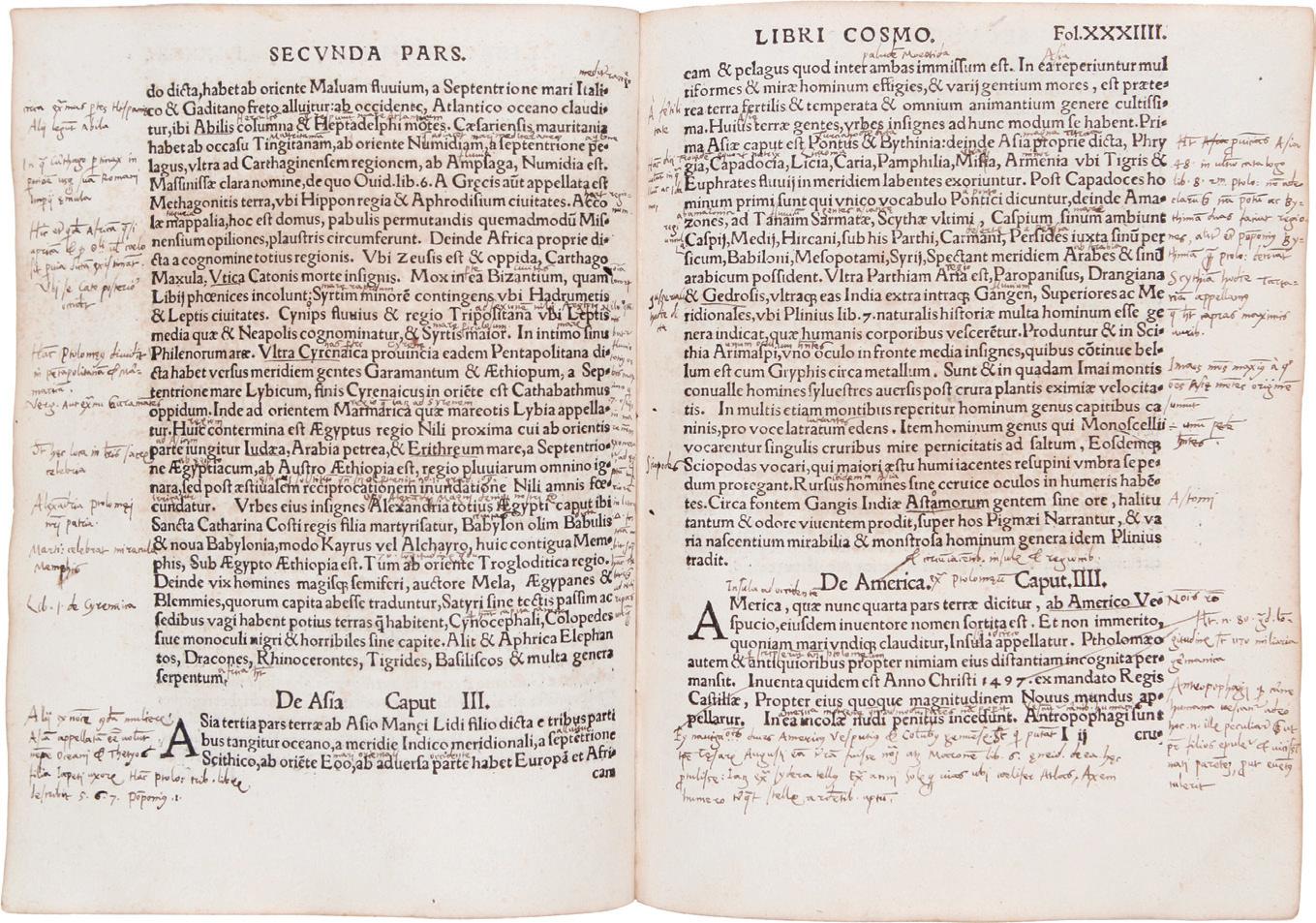

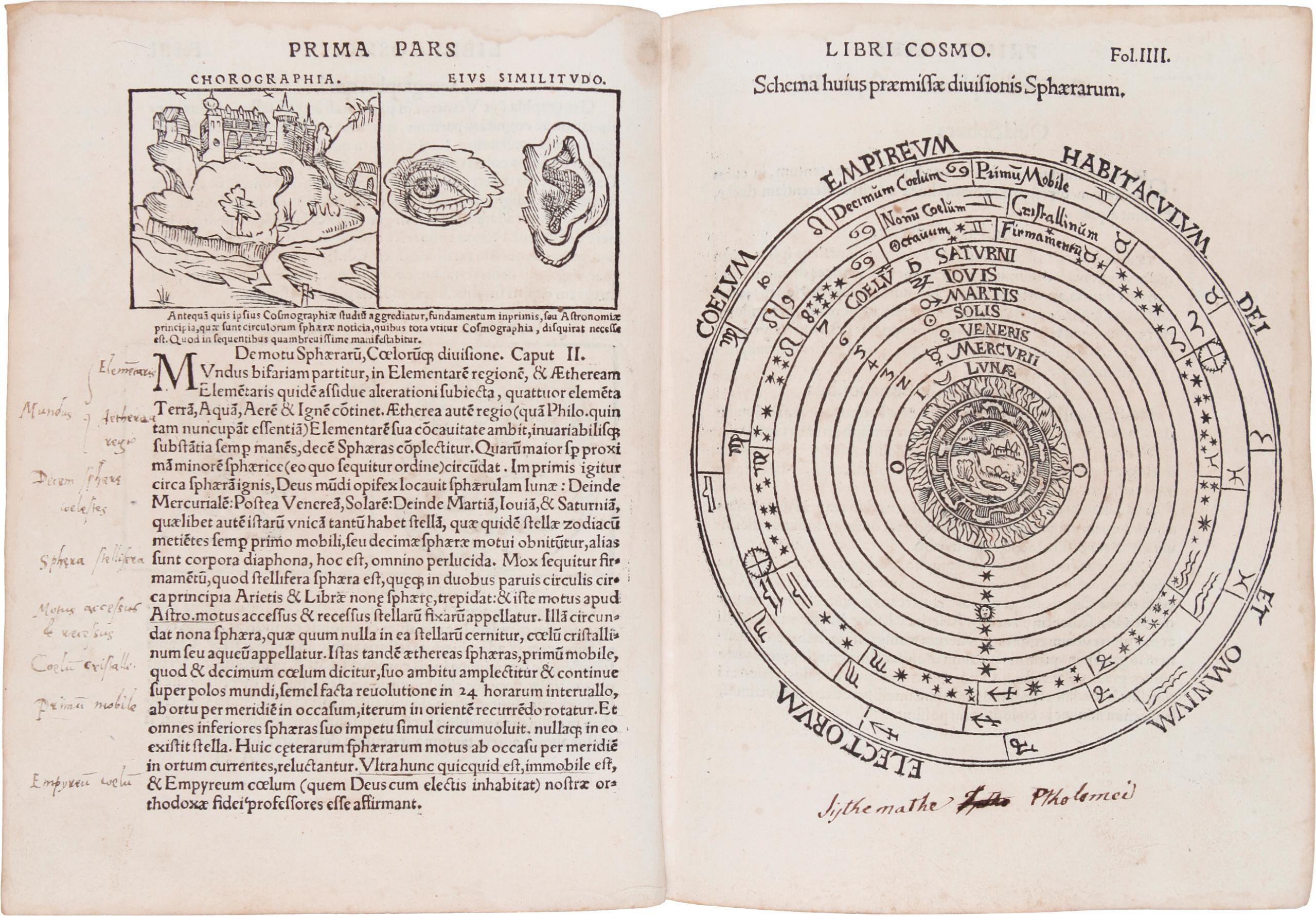

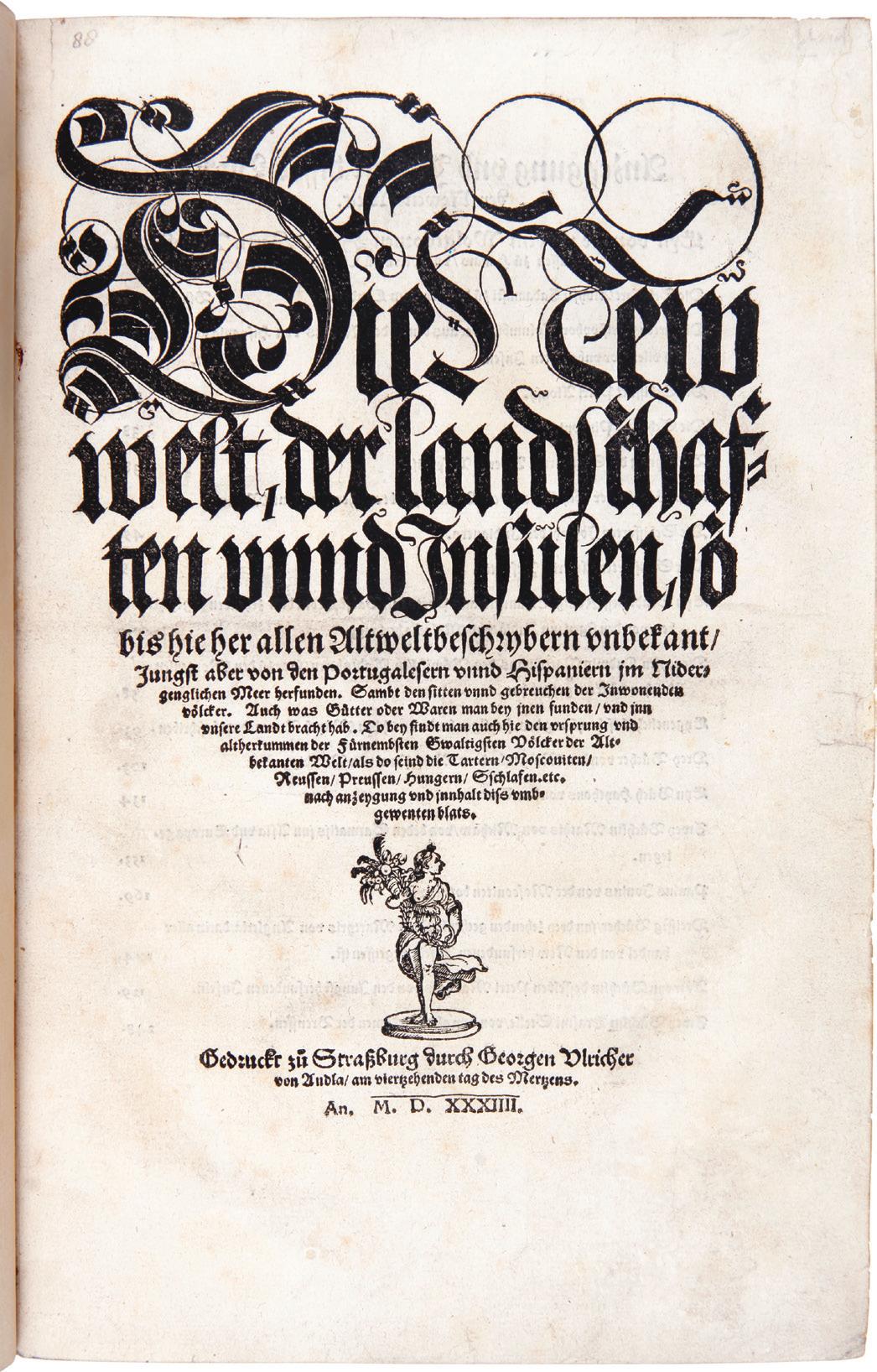

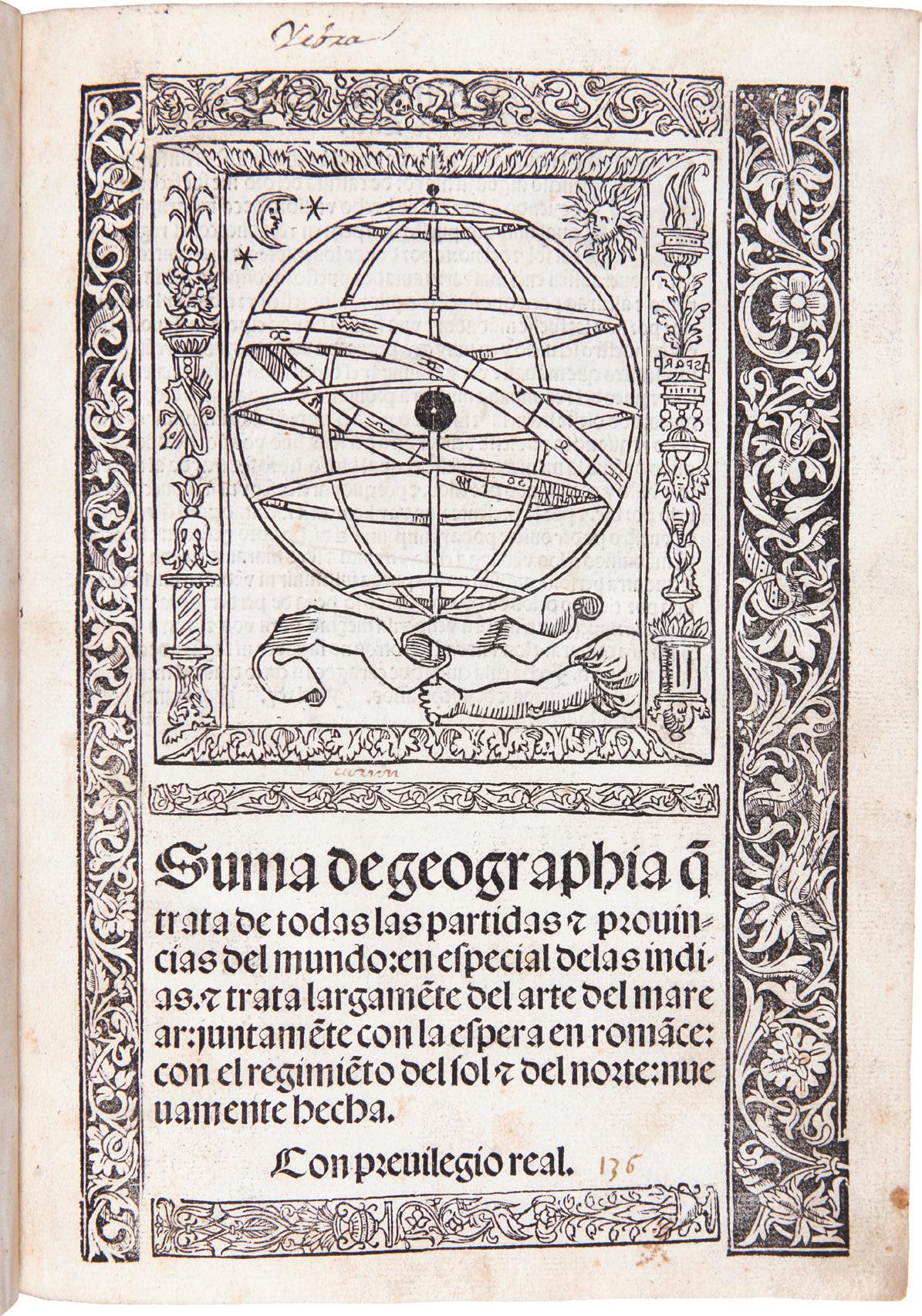

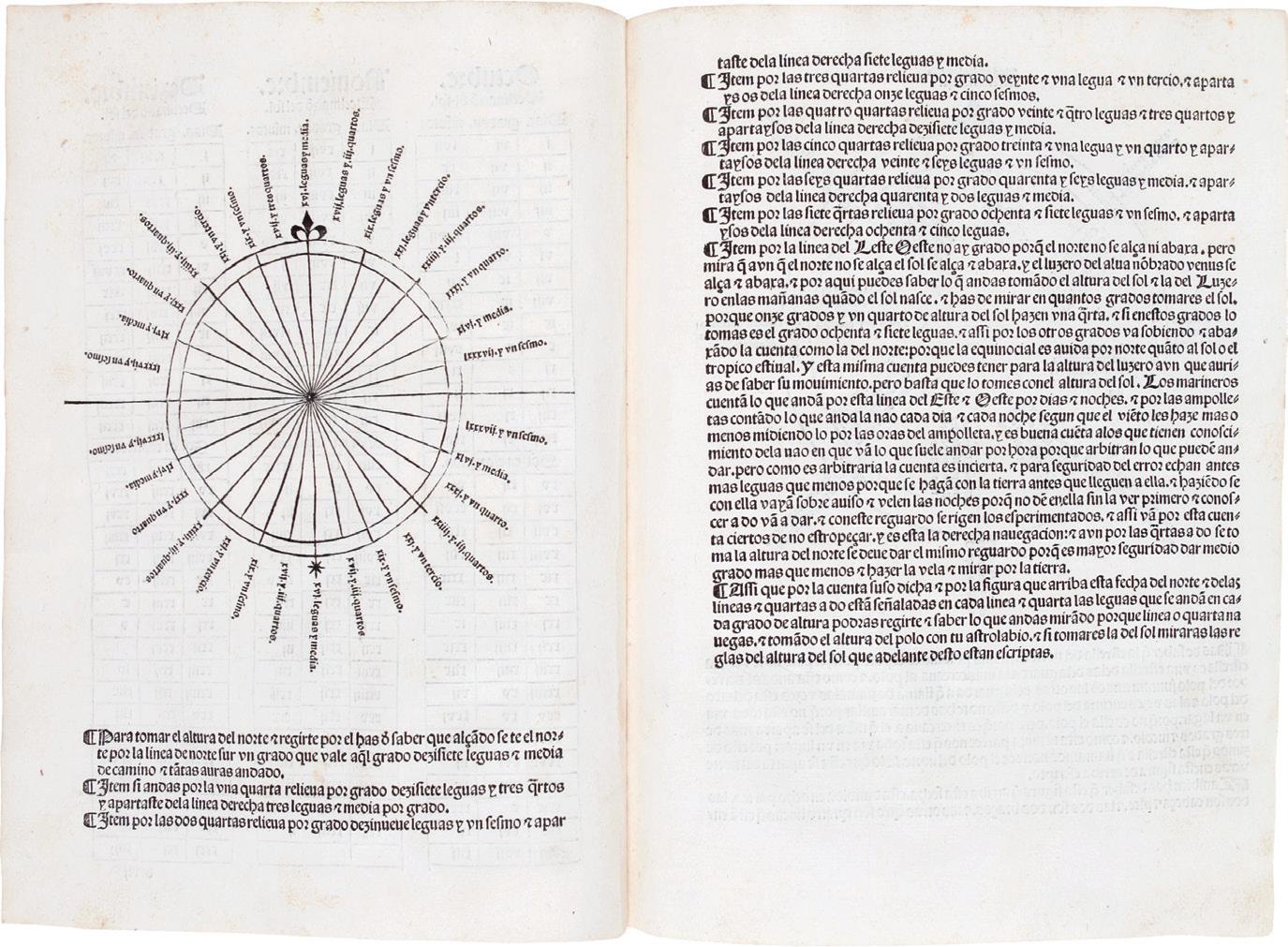

IMPORTANT SAMMELBAND OF WORKS ON NAVIGATION, ASTRONOMY AND AMERICA

15. SCHÖNER , Johann; and Johannes Regiomontanus. [Sammelband of three geographical works by globemaker Schöner, with an incunable edition of Regiomontanus’s astronomical tables]. Nuremberg: Johannes Stuchssen, 1515–1518; Venice: Petrus Liechtenstein for Lucilius Santiritter, 1498.

Together, 4 works in one, quarto (210 × 150 mm). Detailed collations below. Contemporary blindstamped pigskin over bevelled wooden boards, paper label with manuscript title, original clasps and catches. Endpapers renewed. Title page soiled, three words of extended title abraded with loss. Minor toning and foxing in margins of scattered leaves, heaviest in first title and then decreasing; some minor worming in final title, affecting partial letters/ numbers. Some spotting on final three leaves, heaviest on verso of final leaf, which also shows minor loss to a single letter in colophon. Paper repair at lower margin of final leaf affecting outer rule on recto.

An interesting sammelband of titles: taken together these works show the impact of the great transatlantic discoveries, how they were disseminated in Europe during the second decade of the sixteenth century, and how they affected contemporary geographical and celestial knowledge. The volume contains one of the earliest books to name America; the first book to picture a celestial globe; the first book about a celestial globe (known in only two American copies); and an incunable edition of Regiomontanus’s tables, a work which is positively known to have been employed by Columbus on his fourth voyage in 1504. As they form such an integral group, the three Schöner titles were very likely intended to be issued

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 36

together (although they are rarely found thus in American institutions), and along with the Regiomontanus tables, form an up-to-date introduction to geography and practical astronomy of the sort which would have been of great utility to a sixteenth-century navigator.

Schöner (1477–1547), German astronomer, geographer, globe-maker, mathematician, and printer, is best known for his terrestrial globes: that of 1515, after Waldseemüller (1507), the second to show America, and that of 1524, the first to delineate Magellan’s circumnavigation. The connection between Schöner and Waldseemüller could not be stronger: it is highly suggestive of the intellectual culture of these earliest modern geographers that the volume containing the sole extant copy of the Waldseemüller map (purchased by the Library of Congress) as well as the sole extant copy of Waldseemüller’s Carta Marinha (purchased by the Kislak Collection and housed at the Library of Congress) were originally bound in a book owned by Schöner.

1) Schöner, Johann. Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio. Nuremberg, Johannes Stuchssen, 1515. Collates: a8 b6 A–B8 C–G4 H8 I–K8 L6; [15], 65 leaves. Woodcut engraved arms of dedicatee on verso of title and full-page woodcut of a globe, full-page woodcut of an armillary sphere, full-page woodcut of a globe of the world (viewed as a map, and not a repeat of Schöner’s globe), errata slip, and numerous white-on-black initials. Adams S-682; Church 37; European Americana 515/16; Harrisse (BAV) 80 (requiring 2 fewer preliminary leaves); Kraus, Americana Vetustissima, cat. 185, 20; Sabin 77804; Stevenson I.82–3.

Scarce first edition of Schöner’s geographical description of the world, and an important Americanum. The author devotes an entire chapter to the recently discovered continent, titling it “De America” (ff. 60–62), thereby adopting and popularizing Waldseemüller’s description of 1507. This is the second work of Schöner, the greatest globemaker of the sixteenth century, and was intended to accompany his globe, extant in a single example in Frankfurt, and generally regarded as the second (after Waldseemüller’s famous world map) to show America. It is curious that while Schöner’s actual globe illustrates America, its reproduction on A1 recto does not. However, Church refers to the present work as “probably the second, after the various editions of the Cosmographiae Introductio, to contain the word America; the first being the Globus Mundi of 1509.” In other words, it is the third work to use the term “America” to designate the New World. “One of the most important works on globes, and an essential source for any attempt to investigate the early production of Johann Schoener, the greatest globe-maker of the sixteenth century” (Kraus).

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 37

continues overleaf

[Bound with:]

2) Schöner, Johann. Appendices Joannes Schoner Charolipolitani in opusculum Globi Astriferi nuper eodem editum. [Nuremberg: Johann Stuchssen, 1518.] A6; [6] leaves. Full-page woodcut of a globe, repeated on verso of last leaf. European Americana 518/13; Sabin 77798. Not in Church. NUC locates Folger, Harvard, NYPL, Wisconsin; and BL.

[Bound with:]

3) Schöner, Johann. Solidi Sphaerici corporis. Nuremberg: Johann Stuchssen, Calends of August, 1517. A8 B6 C8; [22] leaves. Repeat of woodcut arms on verso of title. Not in Church or European Americana, but mentioned in their entry for Appendices above; Panzer VII, p. 458, no. 128; Sabin 77808 (erroneously calling for 23 ff.; he does not cite an actual copy, but states that he takes the title from Coote’s Bibliography; the copy subsequently acquired by the NYPL has 22 ff.) NUC/ OCLC locates only Harvard and NYPL.

Rare first edition of the first book to illustrate a celestial globe, with the extremely rare and almost always wanting theoretical work of 1517 to which it forms an appendix (bound here with the latter preceding the former). The work was conceived as a descriptive manual to accompany Schöner’s celestial globe of the same year, of which the only known copy is in the Landesbibliothek Weimar. It is unclear whether the two titles published a year apart were issued separately or together. Another edition appeared in 1518, by which time one would think they must circulate together. It is conceivable that the theoretical title was first issued in 1517 to circulate independently, and then together with the instruction manual when the latter was ready; however the modest size of each makes one wonder if they were

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 38

not always meant to accompany the 1515 title, as in the present copy. The Solidi Sphaerici corporis is extremely rare; from his erroneous collation, Sabin did not actually see it and says as much; NUC lists New York Public Library and Harvard, and OCLC adds only a single copy of the 1518 (Bell, University of Minnesota). The New York Public Library copy of the 1517 circulates independently, but the Bell copy is bound with the first work of the present sammelband (although it is lacking the third). The Harvard copies of the three Schöner titles are all held separately. The last copy of the second title we have traced was in one of the Horblit catalogues issued by Kraus (cat. 168, item 169). The Kraus entry claims that the only earlier copy they were able to trace was in Leclerc’s Americana sale of 1878. The Horblit/Kraus copy did not contain the Solidi Sphaerici corporis. [Bound with:]

4) Regiomontanus, Johannes. Ephemerides sive Almanach perpetuum. Venice: Petrus Liechtenstein for Lucilius Santiritter, 1498. 2A8 2B2 A–O8; [122] leaves. Goff R110; BMC V.578; Graesse IV.587; Zinner, Regiomontanus, p. 365, n. 304; Stillwell, Science Awakening I.102.

First and sole Santritter edition of the Regiomontanus tables, which give the true positions of the heavenly bodies day by day. These astronomical and chronological tables formed a critical function for Renaissance scientists and navigators: without them no calculations were possible. “Of all the books written and published by Regiomontanus, this is perhaps the most interesting from the standpoint of general history: Columbus took a copy on his fourth voyage and used its prediction of the lunar eclipse of 29 February 1504 to frighten the hostile natives in Jamaica into submission” (DSB XI.351; referring to Morison, Columbus [1942], pp. 653–4). According to the British Museum Catalogue, this is the only title securely attributed to Petrus Liechtenstein before 1501.

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 39

$200,000

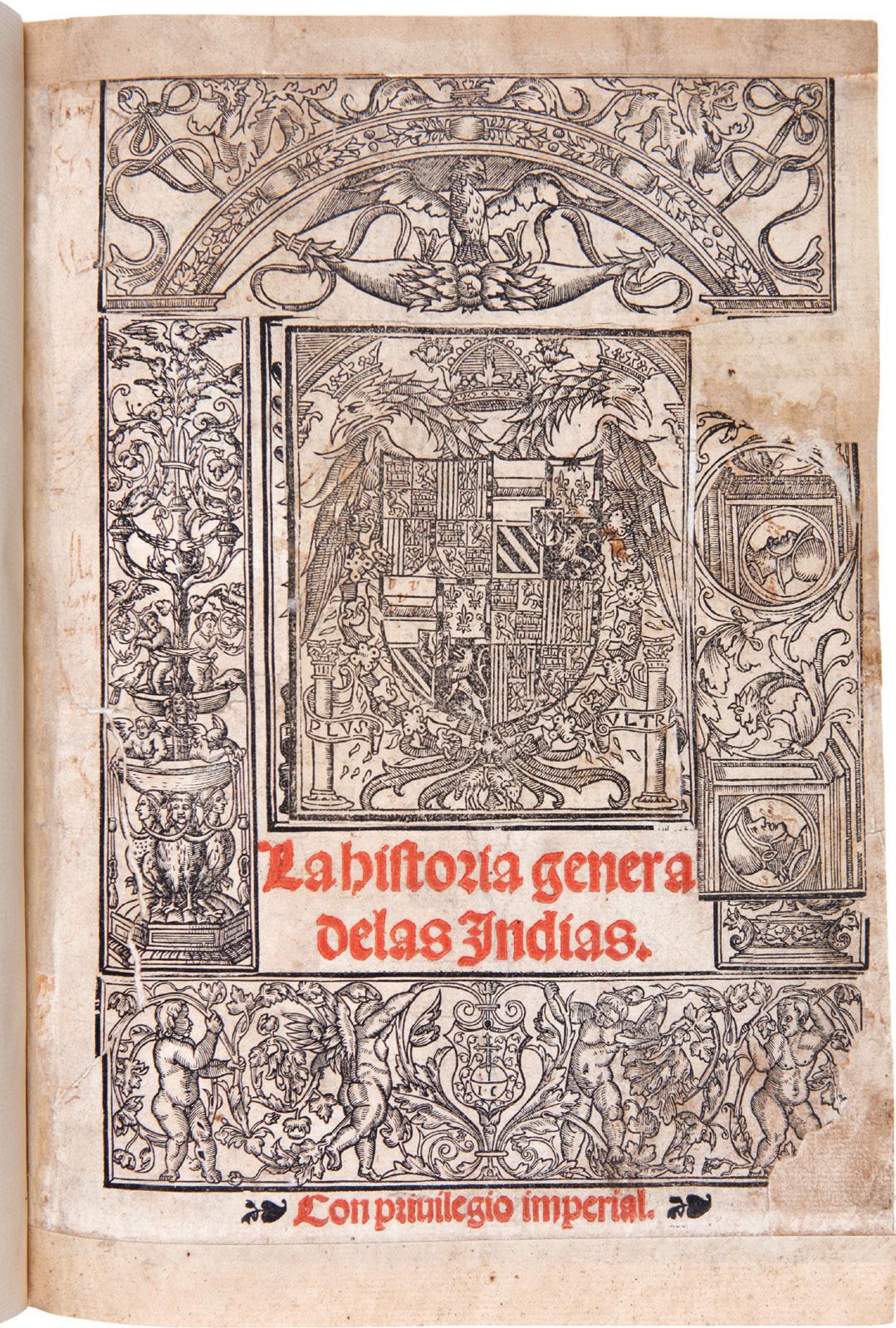

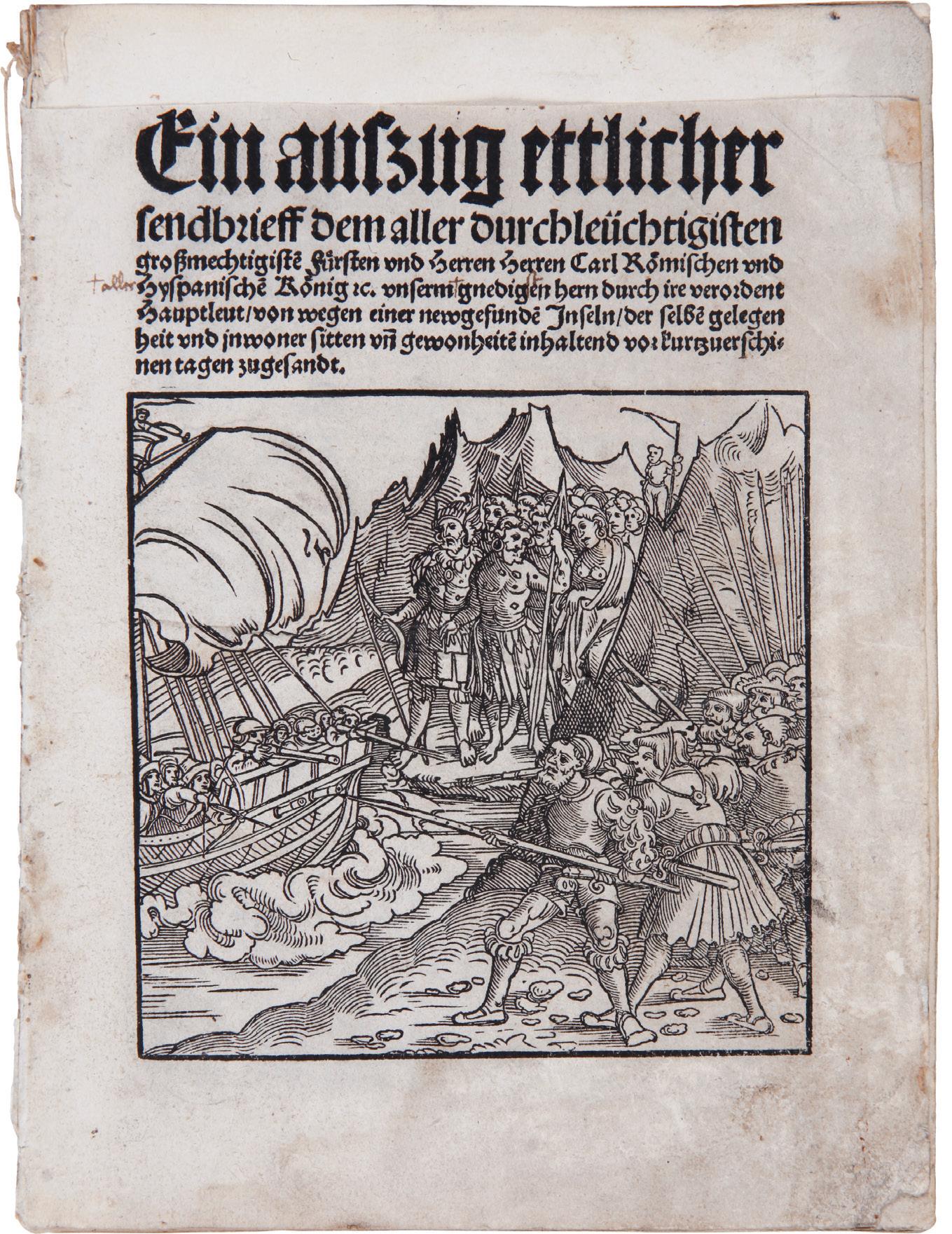

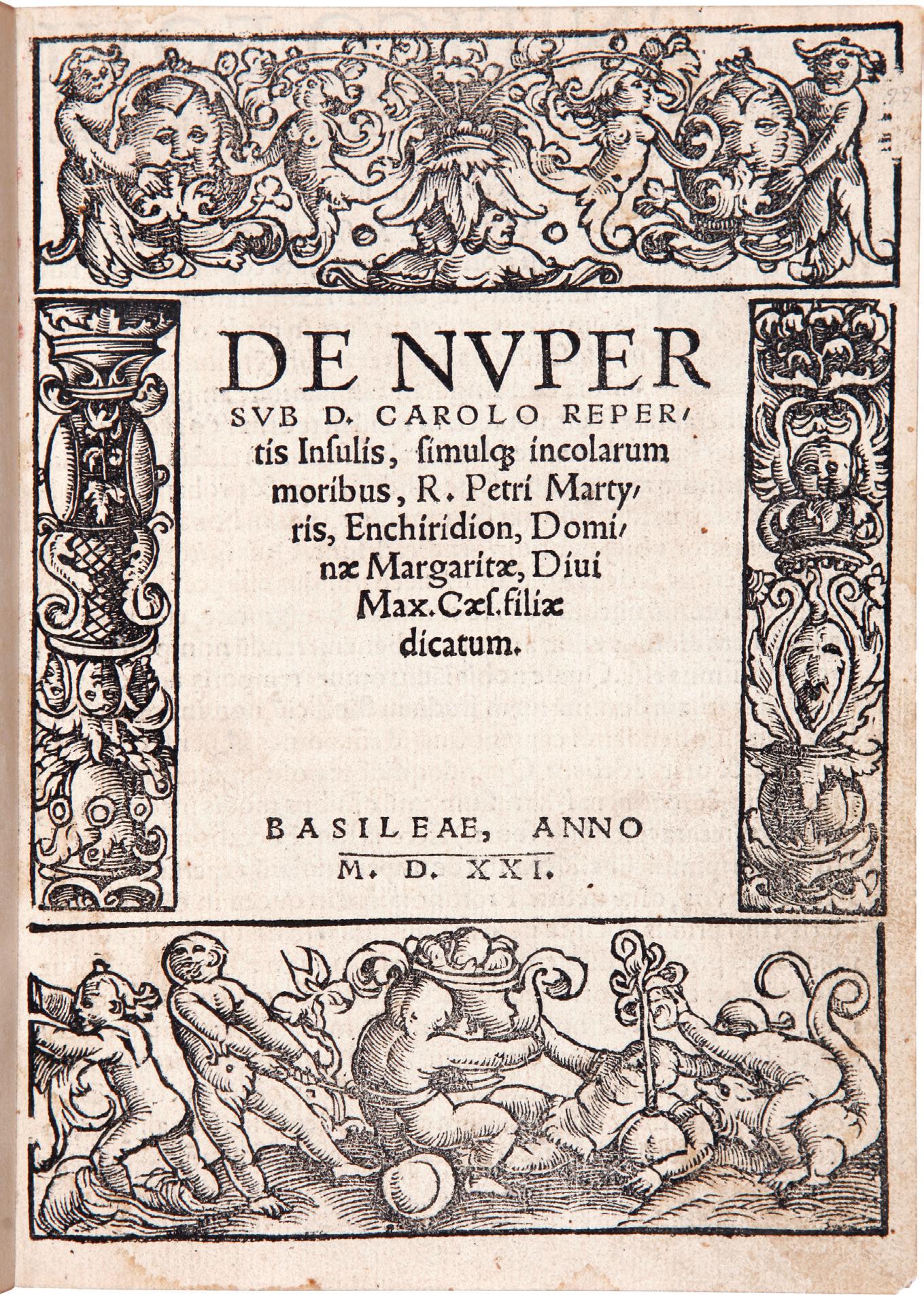

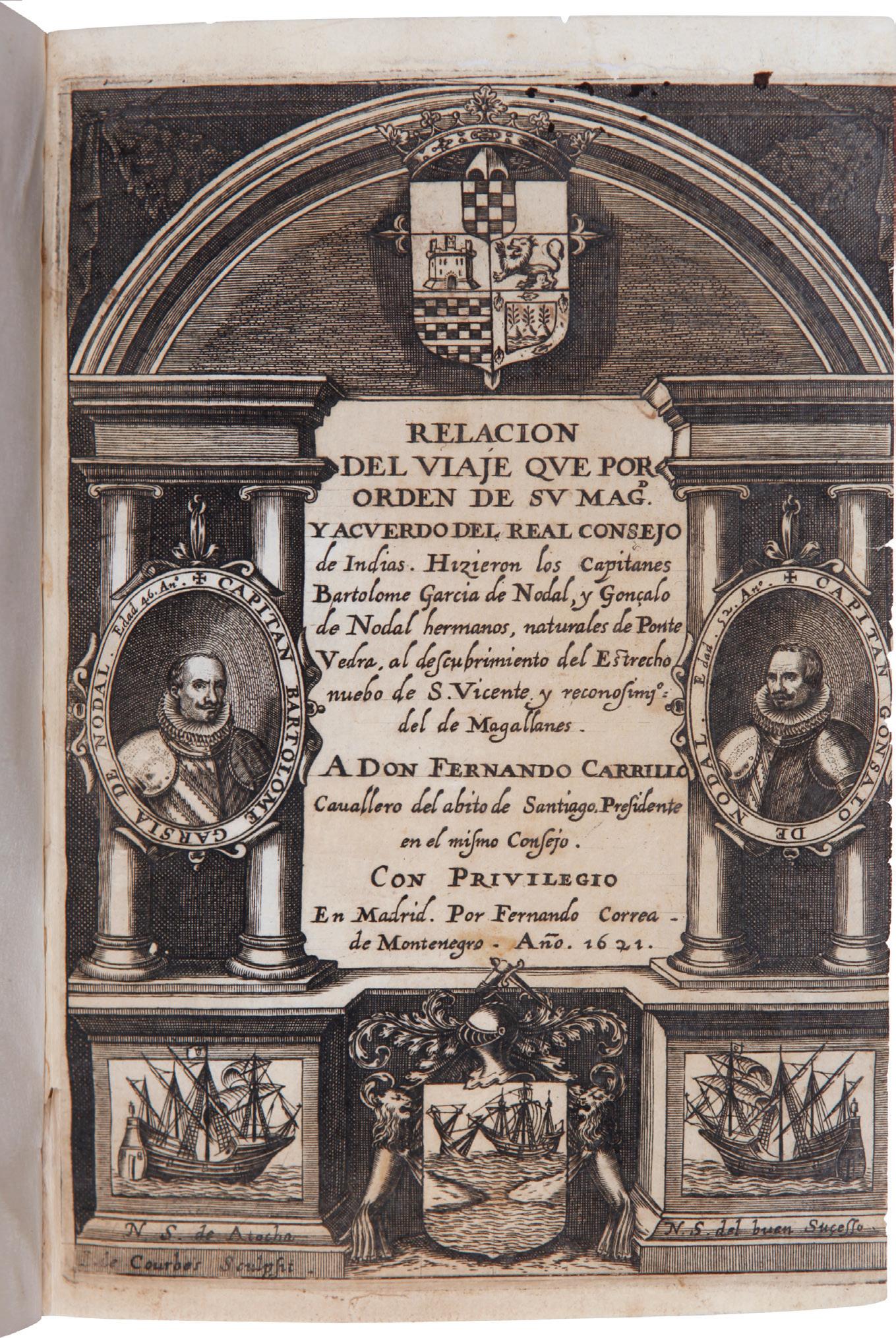

VERY RARE EDITION OF THE FIRST THREE DECADES AND THE FIRST PRINTED ACCOUNT OF BALBOA’S FIRST SIGHTING OF THE PACIFIC

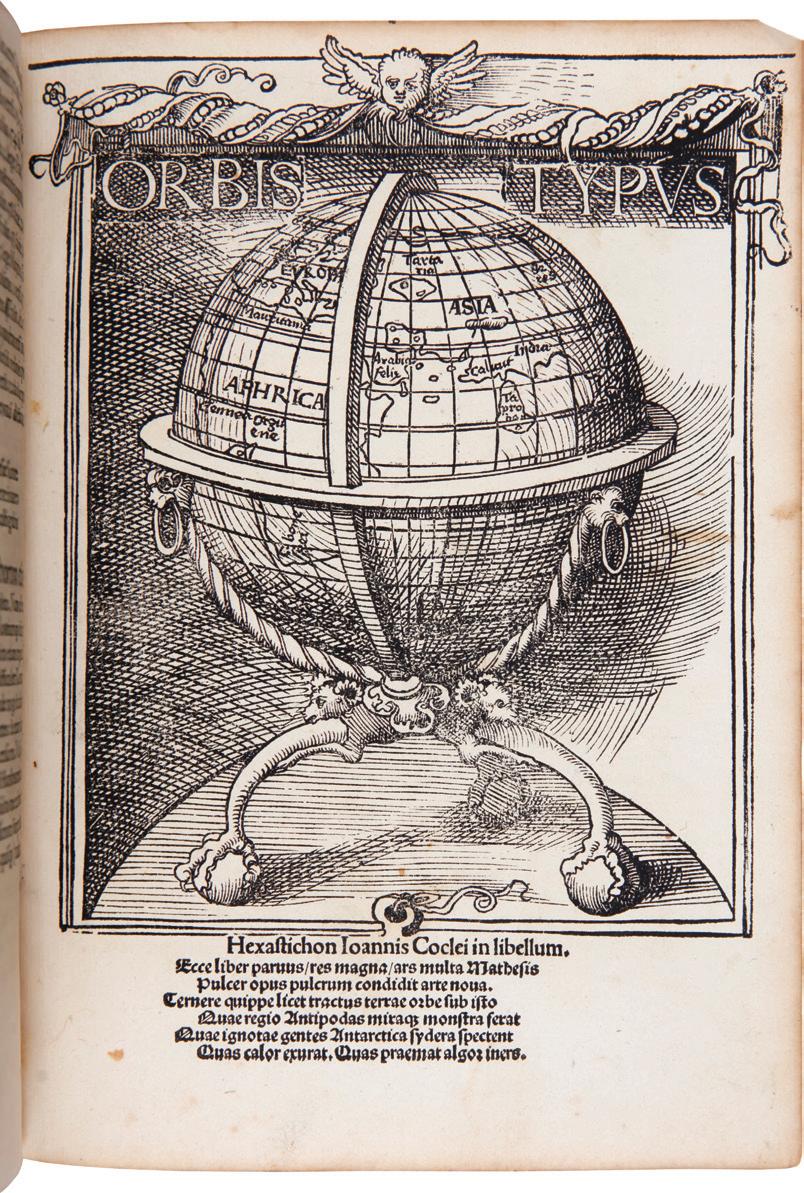

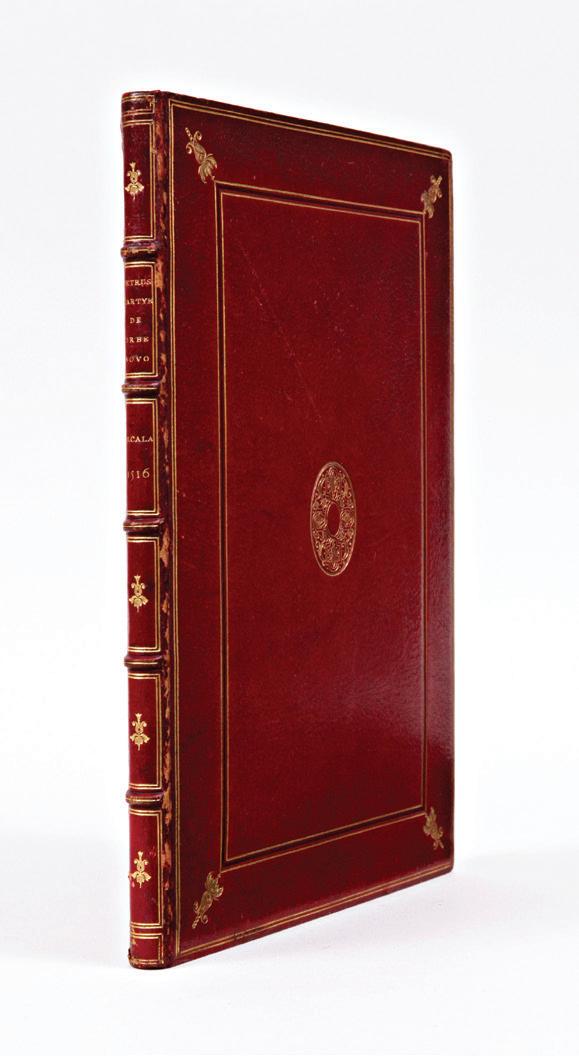

16. ANGHIERA, Pietro Martire d’ [Peter Martyr]. De orbe novo Decades. Alcalà: Arnaldus Guillelmus, 1516.

Small folio (270 × 185 mm): a 6 b–g 8 h6 i 8; 67 (of 68) leaves, lacking blank i5. Title printed within ornamental woodcut border, historiated woodcut initials. Nineteenth-century red morocco by Lortic, medallion with arabesque in central panel, double-gilt ruled, with floral motifs at corners, a second double-gilt border at edges, spine in seven compartments with a variant floral tool, and title gilt, all edges gilt, gilt inner dentelles, decorative endpapers renewed. In a marbled paper slipcase. Expert repair to A6, with a few letters or partial letters over two lines in facsimile or refreshed owing to minor loss. Some discoloration in gutter and minor toning. Generally very good.

Rare first edition, first issue, of the first three Decades of Peter Martyr, containing the accounts of Columbus’s voyages, the first printed account of the expedition of Sebastien Cabot to North America, and the first account of the 1513 sighting of the Pacific Ocean by Vasco Nunez de Balboa. A cornerstone Americanum of

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 40

supreme importance and rarity and among the earliest obtainable editions of any of Martyr’s famed Decades.

Peter Martyr of Anghiera (ca. 1457–1525), a Catholic who served as the tutor of the children of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, was appointed a member of the Council for the Indies. An intimate of Columbus and contemporary of Vasco da Gama, Cortes, Magellan, Cabot, and Vespucci, Martyr had access to numerous firsthand voyage accounts and became the foremost chronicler of the discovery of the New World.

“Peter Martyr was perhaps the first man in Spain to realize the importance of the discovery made by Columbus. Where others beheld but a novel and exciting incident in the history of navigation, he, with all but prophetic forecast, divined an event of unique and far-reaching importance. He promptly assumed the functions of historian of the new epoch whose dawn he presaged, and in the month of October, 1494, he began the series of letters to be known as the Ocean Decades, continuing his labors, with interruptions, until 1526, the year of his death. The value of his manuscripts obtained immediate recognition; they were the only source of authentic information concerning the New World, accessible to men of letters and politicians outside Spain. His material was new and original; every arriving caravel brought him fresh news; ship-captains, cosmographers, conquerors of fabulous realms in the mysterious west, all reported to him; even the common sailors and camp-followers poured their tales into his discriminating ears. Las Casas averred that Peter Martyr was more worthy of credence than any other Latin writer . . . It is their substance, not their form, that gives Martyr’s writings their value, though his facile style is not devoid of elegance, if measured by other than severely classical standards. Not as a man of letters, but as an historian does he enjoy the perennial honor to which in life he aspired. Observation is the foundation of history, and Martyr was preeminently a keen and discriminating observer, a diligent and conscientious chronicler of the events he observed, hence are the laurels of the historian equitably his” (MacNutt, Introduction to De Orbe Novo: The Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D’Anghera [1912]).

Martyr’s Decades are of primary importance to the early history of America. Written in epistolary form, the First Decade (i.e. ten letters) relates entirely to Columbus and his voyages, as well as those of Nino and Pinzón. Completed around 1501, a manuscript transcript was given to an Italian who printed an abridged and unauthorized piracy in 1504, titled Libretto de tutta la navigatione de Re de Spagna. This work was reprinted in 1507 in the Paesi nuouamente retrouati together with some account of early Portuguese navigation. In the preface to the present work, Martyr complained of it having been printed without his consent. He himself printed the First Decade in 1511 in Seville, which included an account of his expedition to Egypt and an additional account of events from 1501 to 1511.

In 1516, Martyr arranged the publication of the present work, assisted by Latinist Antonio de Nebrija, comprising the second authorized publication of the First Decade and the first publication of the Second and Third Decades; that is, covering the period of over twenty years from Columbus’s first voyage. The Second and Third Decades are of considerable importance, the first of these being

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 41

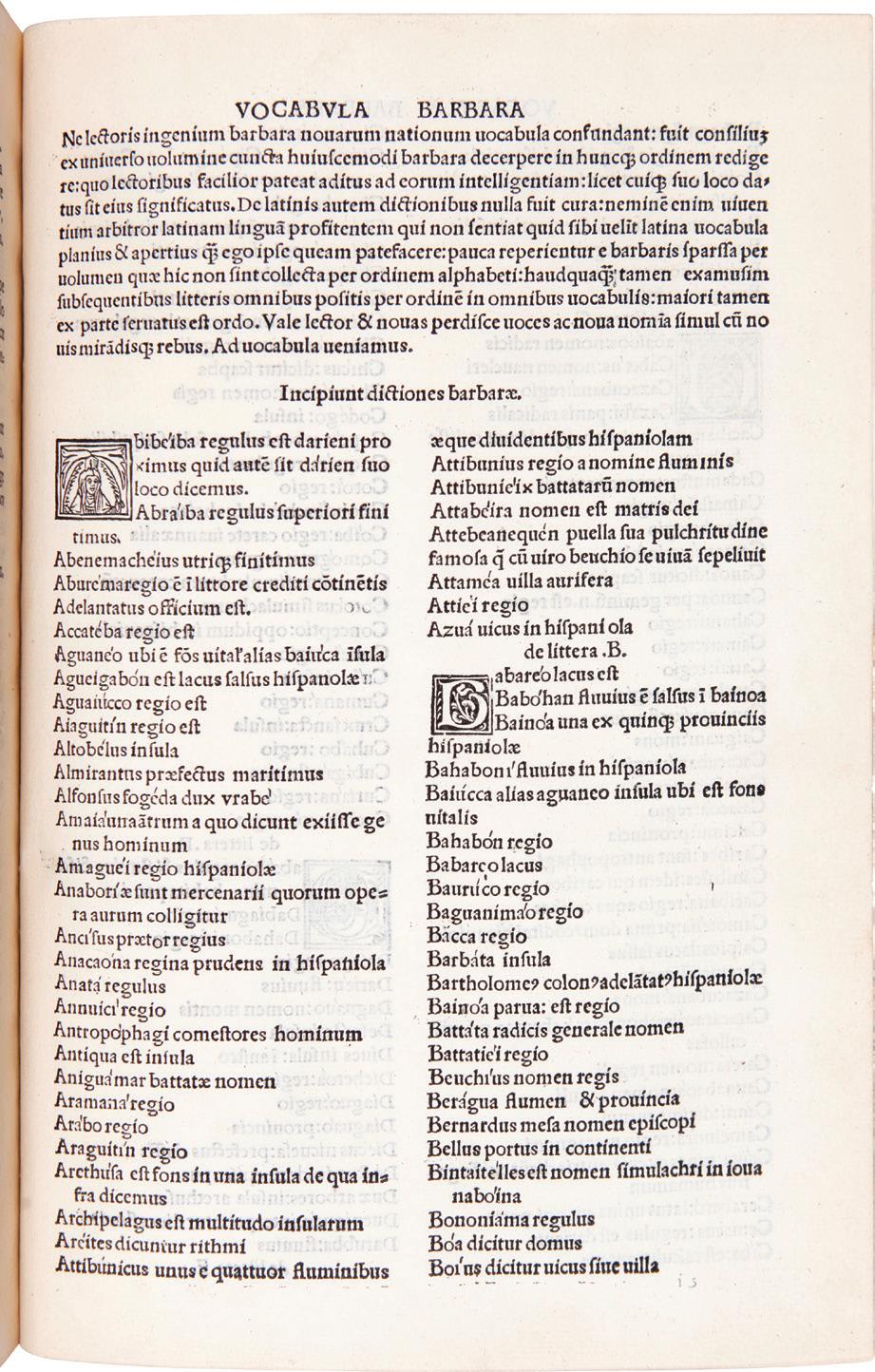

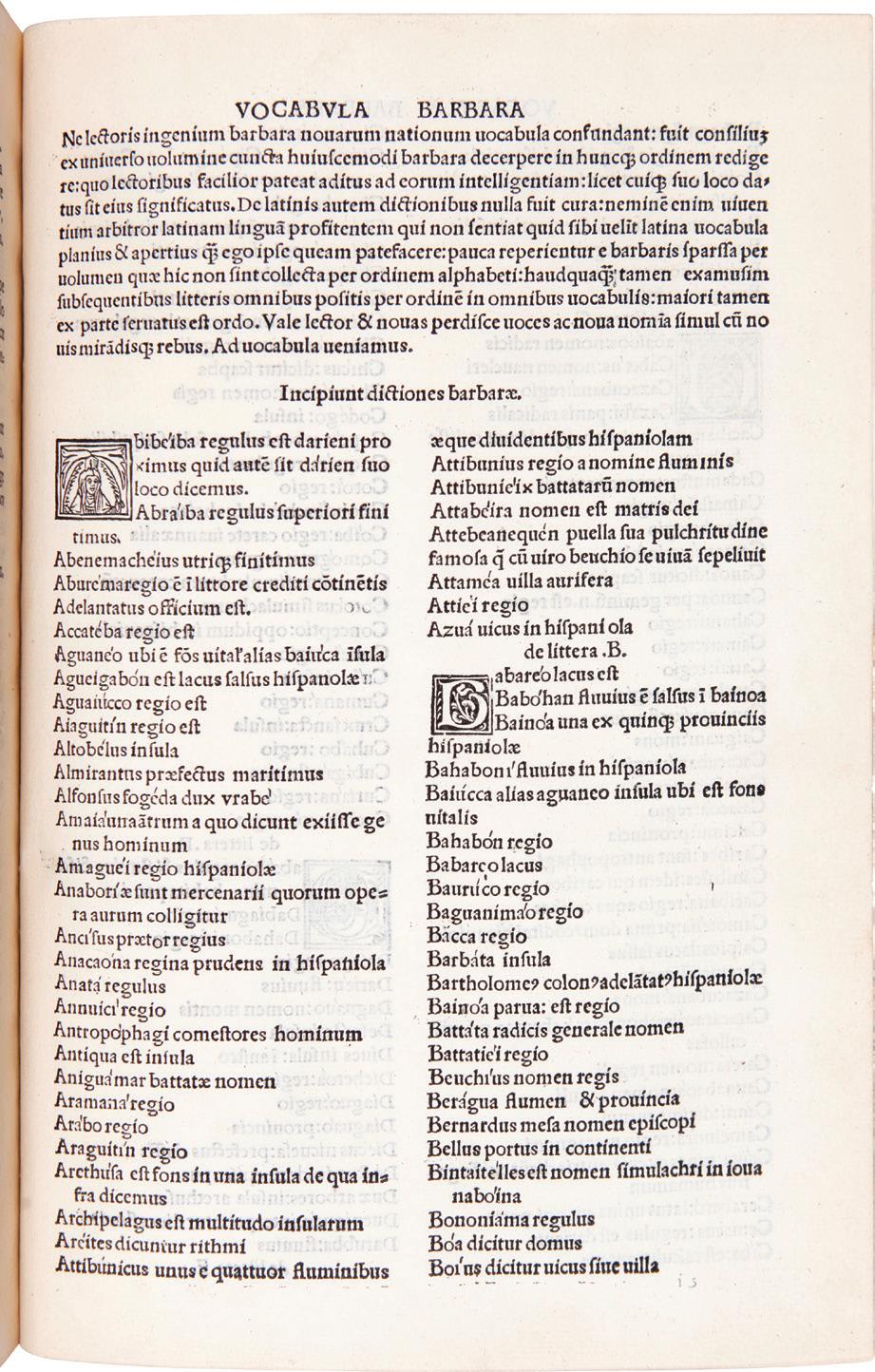

devoted to the exploits of Ojeda, Nicuesa, and Balboa; the other giving an account of the discovery of the Pacific Ocean by Balboa (communicated to Martyr by Balboa himself), of the fourth voyage of Columbus, and furthermore of the expeditions of Pedrarias, Cabot and others. Notably it includes the first attempt at a vocabulary of native American words, headed “Vocabula Barbara.”

Two issues of the 1516 Decades are noted: with or without a 16-leaf appendix concerning his travels to Egypt known as the Legatio Babylonica. The text of the title page of the two issues differs, with one referencing the presence of the Legatio. As that section supplements the preceding, it is generally assumed that examples without the section, or reference to it on the title page, are the first issue. We find no other example of the 1516 Peter Martyr on the market since H. P. Kraus offered one in his famed catalogue Americana Vetustissima (Cat. 185, item 21) also without the Legatio: “It is the present publication of the first three Decades which really made Martyr’s reputation and gained him an official position as member of the Council of Indies.”

Arents 2; Church 39b; European Americana 516/1; Harrisse (BAV) 88; JCB (3) I:66; Medina (BHA) 53; Palau 12590; Sabin 1550; Streeter Sale 7; Streeter, Americana-Beginnings 4.

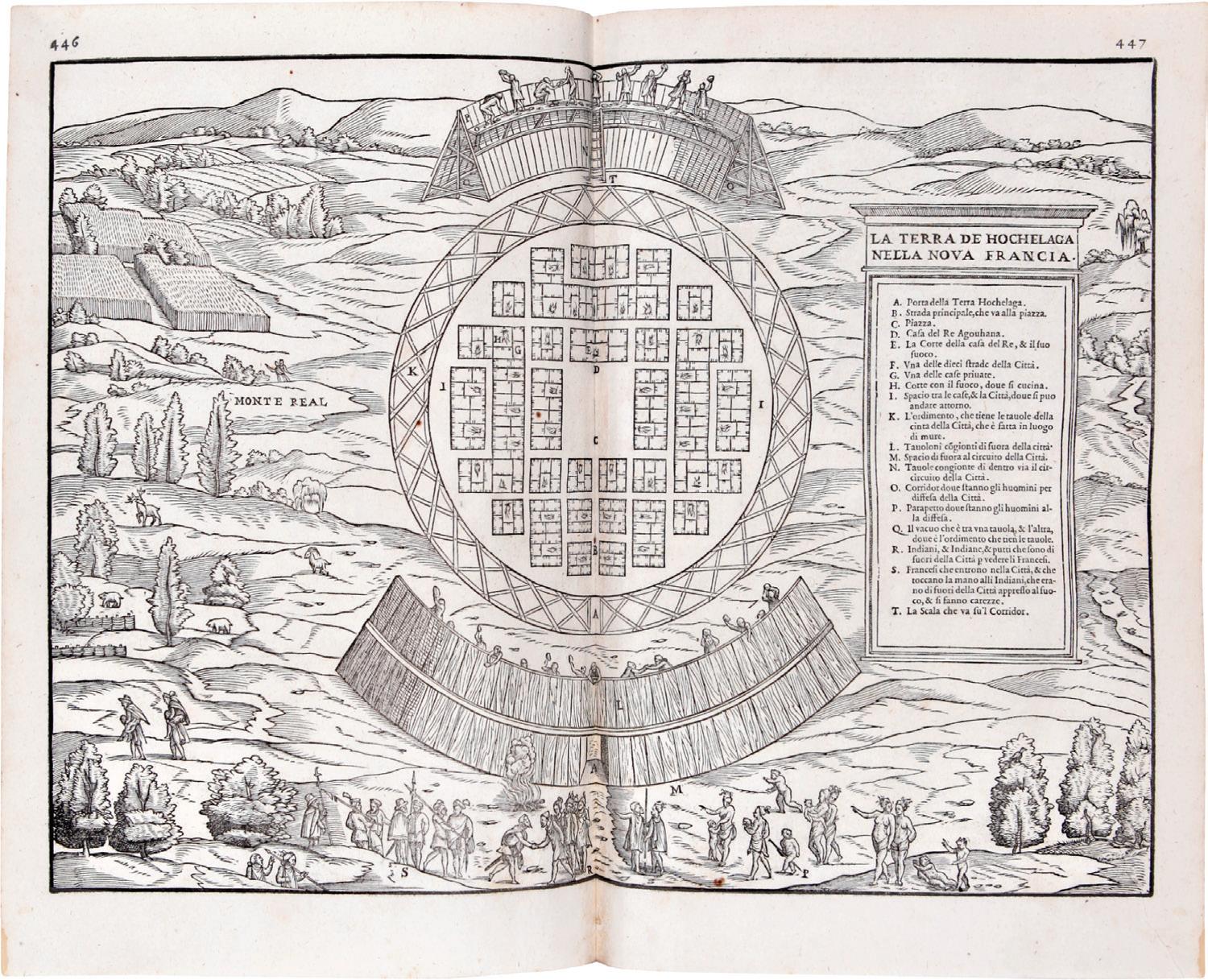

SOLD WITH ONE OF THE EARLIEST PRINTED DESCRIPTIONS OF INDIGENOUS CANADIANS

17. EUSEBIUS CAESARENSIS; [Johannes Multivallis;] and others. Episcopi Chronico[n]. Paris: Henricus Stephanus [i.e. Henri Estienne], 1518.

Quarto (229 × 170 mm): a–b 8 c 4 A–X 8 Y 6; [20], 175 leaves [i.e. 173, with errors in foliation as issued]. Title within ornamental woodcut border. Text printed in red and black with woodcut initials throughout. Later vellum with slightly yapp edges, manuscript spine title. Vellum bowed and somewhat stained. Scattered foxing and soiling, occasional dampstaining to margins, lower corner of final leaf repaired, not touching text.

This second edition of this universal history of secular and ecclesiastical events from the time of Abraham up to 1511, includes entries on the discovery and early exploration of the New World. Events through the year 325 are taken from the Chronicron of Eusebius, and continued thence to the mid-1400s by Saint Jerome, Mattia Palmieri of Pisa, and others. The chronicle has been edited and extended from Palmieri’s time in the mid-1400s to 1512 by Johannes Multivallis, and was first published in this form by Henri Estienne the elder in that year.

While the exploits of early explorers such as Alvise Cadamosto are listed among ecclesiastical and secular successions, natural phenomena, and wars, the first mention of the New World does not come until 1509. The entry, one of the longest in

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 42

the entire chronicle and filling twenty lines of text, is of the greatest importance and describes the arrival in Rouen of seven indigenous Americans, most likely those brought from Canada by the French explorer Thomas Aubert, who visited Newfoundland in 1508. The description in this work claims (in translation) that the seven were brought to Rouen “from that island called the New World, with their small boat [i.e. a canoe], costumes, and weapons.” They are said to have markings “drawn like pale veins from the ear to the middle of the chin,” hair which is “black and long, like a horse’s mane,” and to have no religion. The text also describes their dress (“nude or garbed in the skin of animals such as bears, deer, or sea cows”), diet (“Their food: Roasted meat. Drink: Water. They do not use bread, wine, or money”), and arms (“bows strung with cords of animal intestines or sinew”).

This second printing is largely identical to the first Estienne edition of 1512, excepting a few minor typographical changes and the incorporation of the first edition’s errata. A beautifully printed post-incunable, including a remarkably early description of Canadian First Nations.

Adams E1073; European Americana 518/3; Harrisse (BAV) 71; Harvard French Sixteenth Century Books 217; Renouard, Estienne 9; Sabin 23114.

$6,500

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA 43

THE PARSONS COLLECTION 44

ONE OF THE EARLIEST MEDICAL WORKS RELATING TO AMERICA

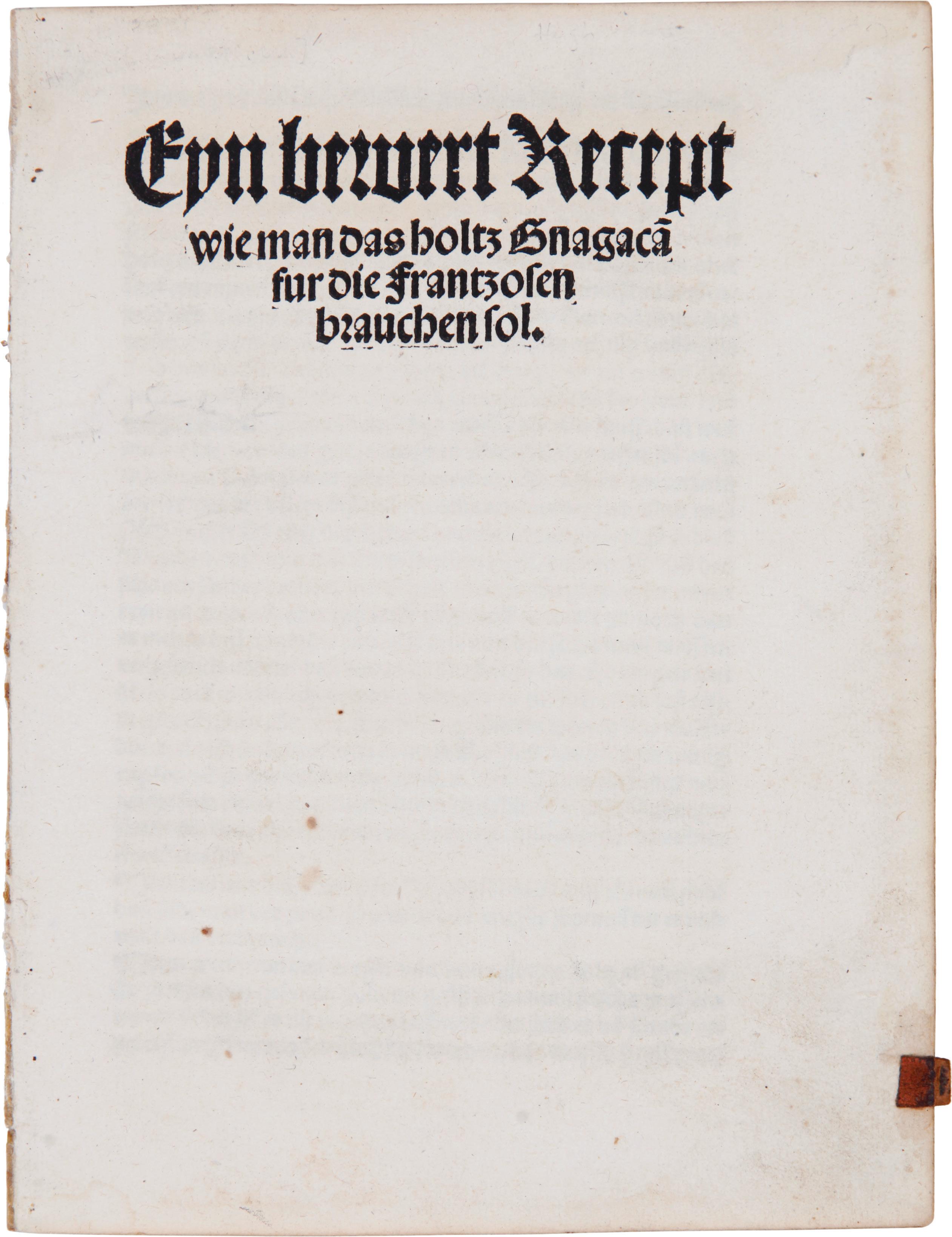

18. (MEDICINE.) Eyn bewert Recept wie man das Holtz Gnagacam fur die Frantzosen brauchen soll. [Nuremberg: J. Gutknecht, 1518.]

Quarto (198 × 150 mm): [4] leaves. Disbound. In a cloth chemise and half morocco and cloth slipcase, spine gilt. Early leather tab on fore-edge of first leaf. Very slight soiling and dampstaining in margins. A very good copy.

An extremely rare copy of one of the earliest pamphlets promoting the use of the guaiacum wood as a cure for syphilis and providing specific instructions for the plant’s use. Printed circa December 1518, the work was probably published the same month and year as an equally rare Augsburg pamphlet with a similar title, Ain Recept ecept von ainem holtz zu brauchen fur die Kranckhait der Frantzosen. Both pamphlets are only recorded at the same single location in the United States. The sole earlier work specifically about guaiacum noted in European Americana is Niccolò Campani’s Lamento . . . sopra il mal fancioso, a description of the “French Disease” in verse printed in Siena, circa 1515.

Although works about syphilis were published even prior to 1500, this pamphlet’s directions for curing the disease with the American plant guaiacum are among the first to be published, predating Ulrich von Hutten’s popular instructions for the cure which first appeared in 1519. John Alden notes in the preface to the first volume of European Americana that the “appearance in Europe of syphilis at the end of the 15th century seems, all too inexorably [from America], due to its transmission from Hispaniola, beginning with Columbus and his men . . . The consequences for the bibliographer will be readily evident, for as the armies of European powers traipsed across the Continent they spread this new scourge, reflected in the writings of the period . . . And even if it were at best dubiously American, treatment for it usually employed medicines derived from American sources, chiefly Guaiacum . . . introduced from the Caribbean.” Today, the American origin of the disease is not disputed.

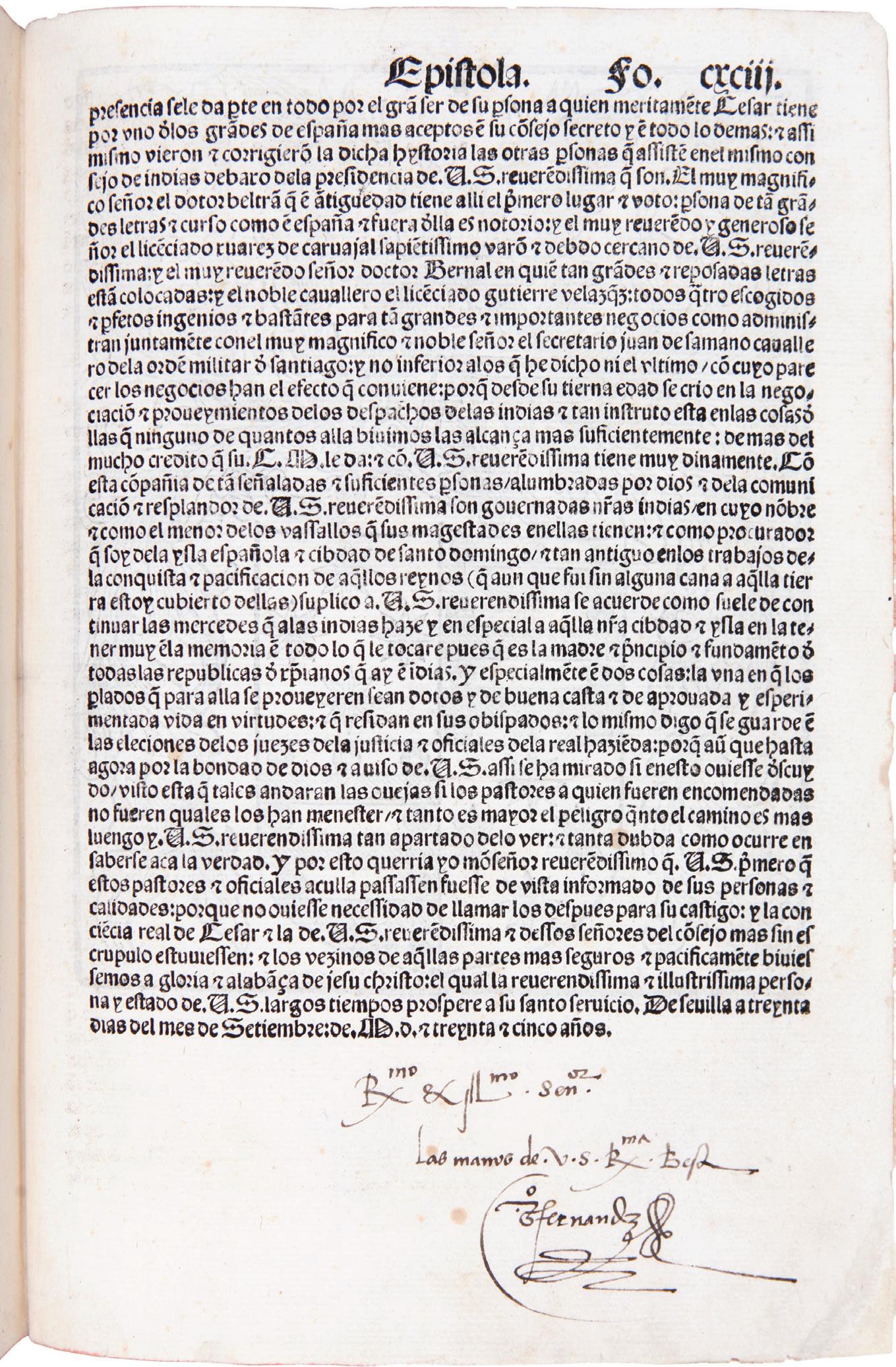

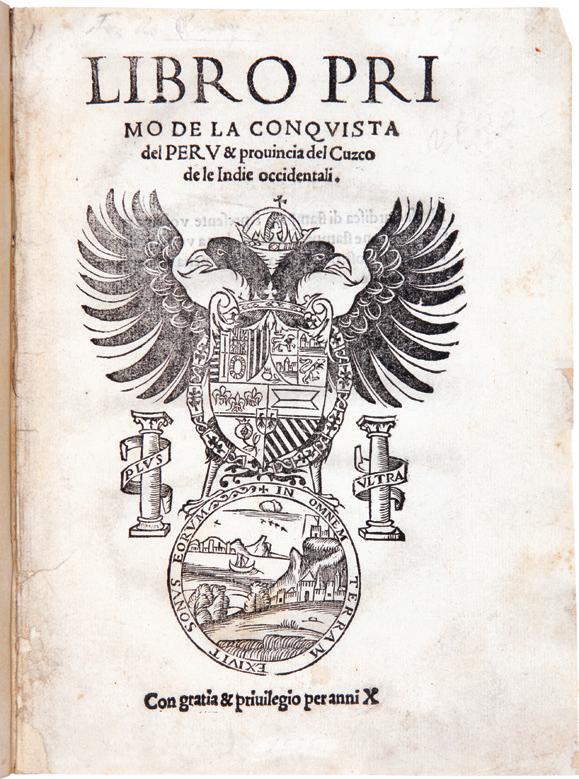

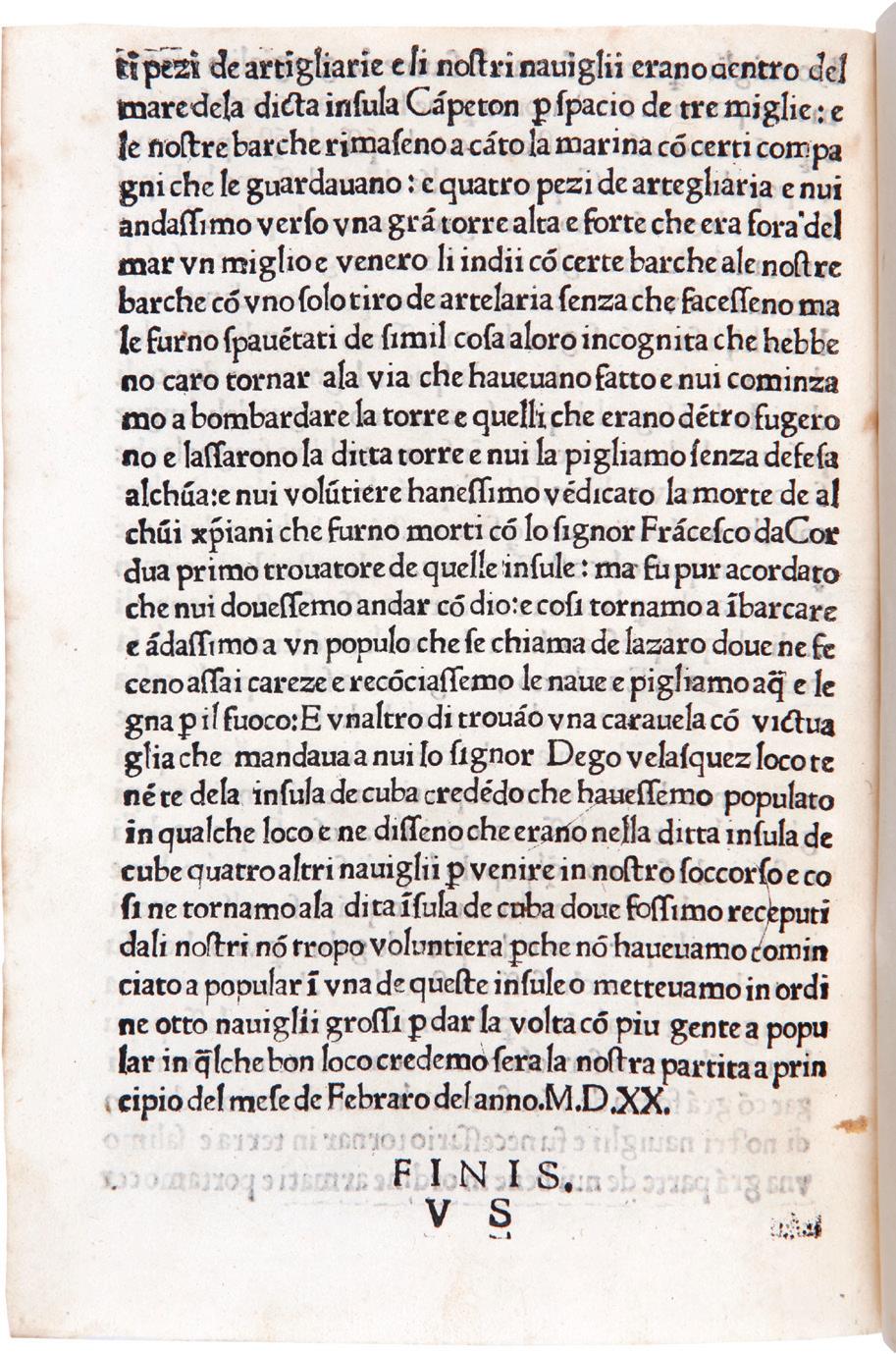

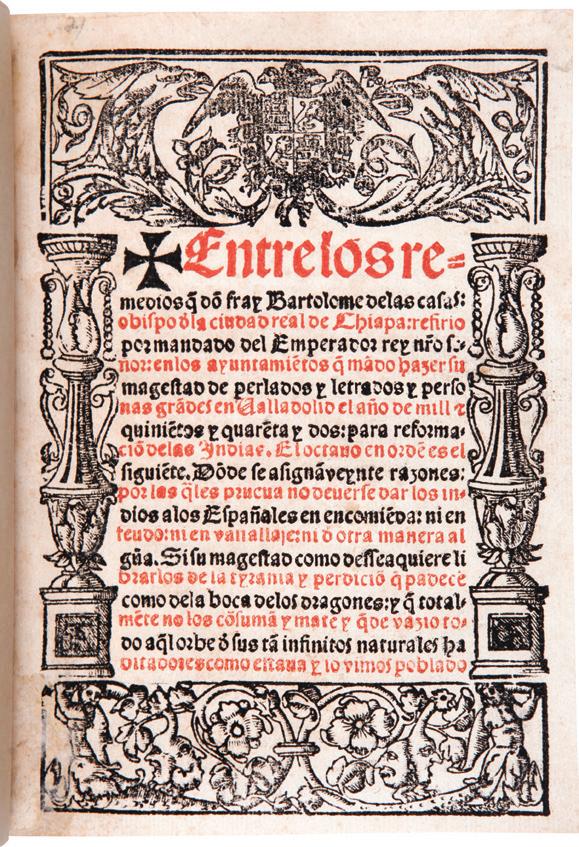

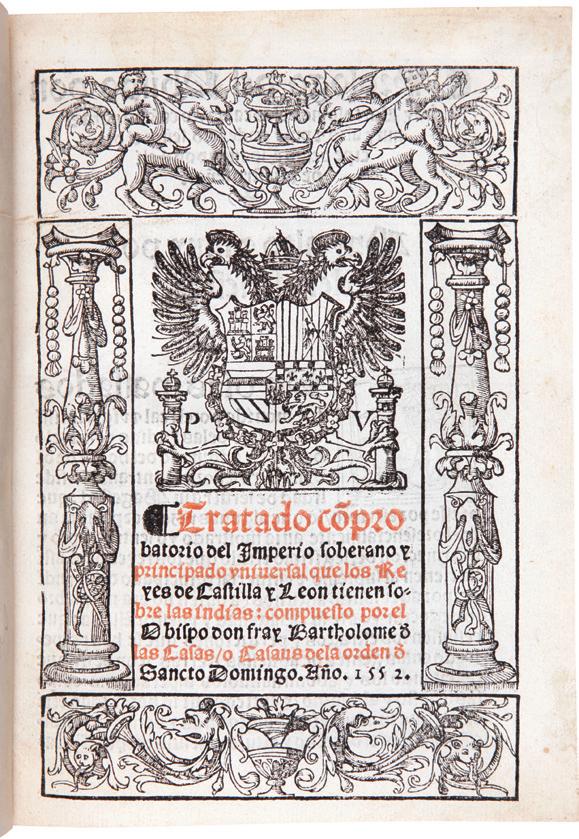

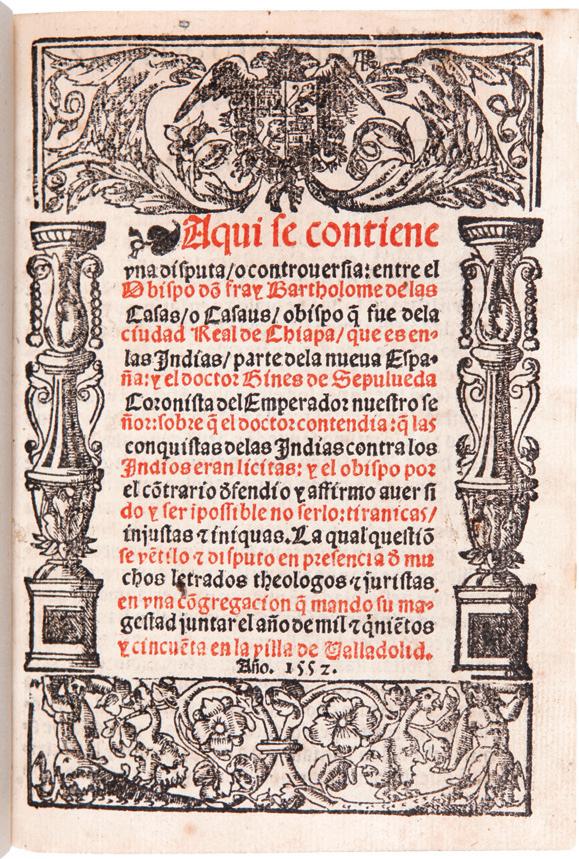

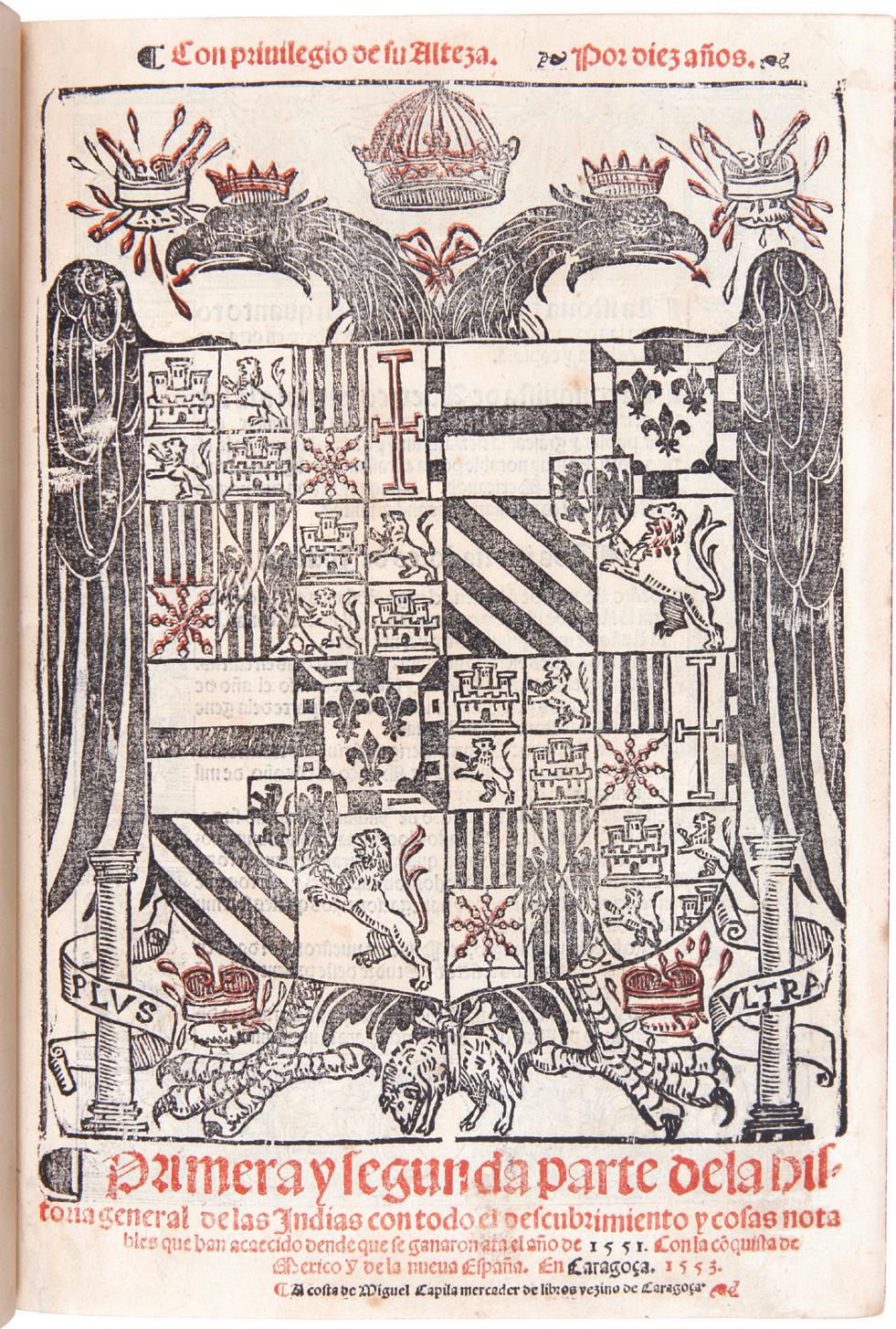

The present pamphlet includes itemized instructions for soaking and boiling the wood, drinking the resulting liquid, and inhaling smoke from the wood-fire. A regimen of medication, purging, fasting, and rest is suggested for a period of twenty-five days. The patient is not to be agitated, but should be surrounded by cheerful company. Once recovered, the patient can go outside, but sex is not allowed for the following two months. Other recommendations regarding diet are also provided.