11 minute read

FEATURE

by Susan Friedland

Sarah Maslin Nir

Loving Horses and Healing the World Through Words

When Simon and Schuster reached out to New York Times reporter Sarah Maslin Nir to ask her to write a book based on her Pulitzer Prize-finalist series Unvarnished that investigated the exploitative labor practices of New York City nail salons, she said no. Sarah felt she had already written the book over the course of the year she had been reporting on the topic. When asked what subject she would want to write a book about, the answer was easy: horses.

“I dreamed up the idea for Horse Crazy as more of an almanac of horses and the stories I’ve been told about them as I traveled all over the world.” In her 800word email to the publisher fleshing out the idea, Sarah closed with, “This isn’t my story. This is a story of the horses I’ve met.” The editor responded that he really liked the concept but wanted to push back on one thing.

He told Sarah, “This is your story.”

“As a journalist, using the word ‘I’ is beaten out of us,” Sarah laughed. “I never would have thought to write about myself, but I realized horses are so deeply personal. Something I like to say is when you look at a dog or a cat, you think, ‘Oh that’s cute.’ But when you look at a horse, you feel something kind of tug, the way a mountain vista makes you feel, or looking out at the sea. And that to me speaks to how personal the experience of a horse is, so of course it became my story.”

Sarah’s memoir Horse Crazy: a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal is peppered with horses she’s known and loved and stories of equestrians ranging from Dr. George E. Blair, who taught her the erased history of the Black cowboy, to a Chappaquiddick resident who smuggles Marwari semen into the United States. Through her artful narratives, readers join Sarah’s immersion in the equine world from a fox hunting gallop to riding in Central Park serving on the city’s Auxiliary Mounted Patrol, to observing Pony Penning Day on Chincoteague Island, and beyond. Her passion for ponies pops off the pages from the front cover’s gold Wesley Dennis foal design hidden under the book jacket (a nod to beloved horse book author Marguerite Henry) to the final page.

THE MAGNETIC PULL OF HORSES

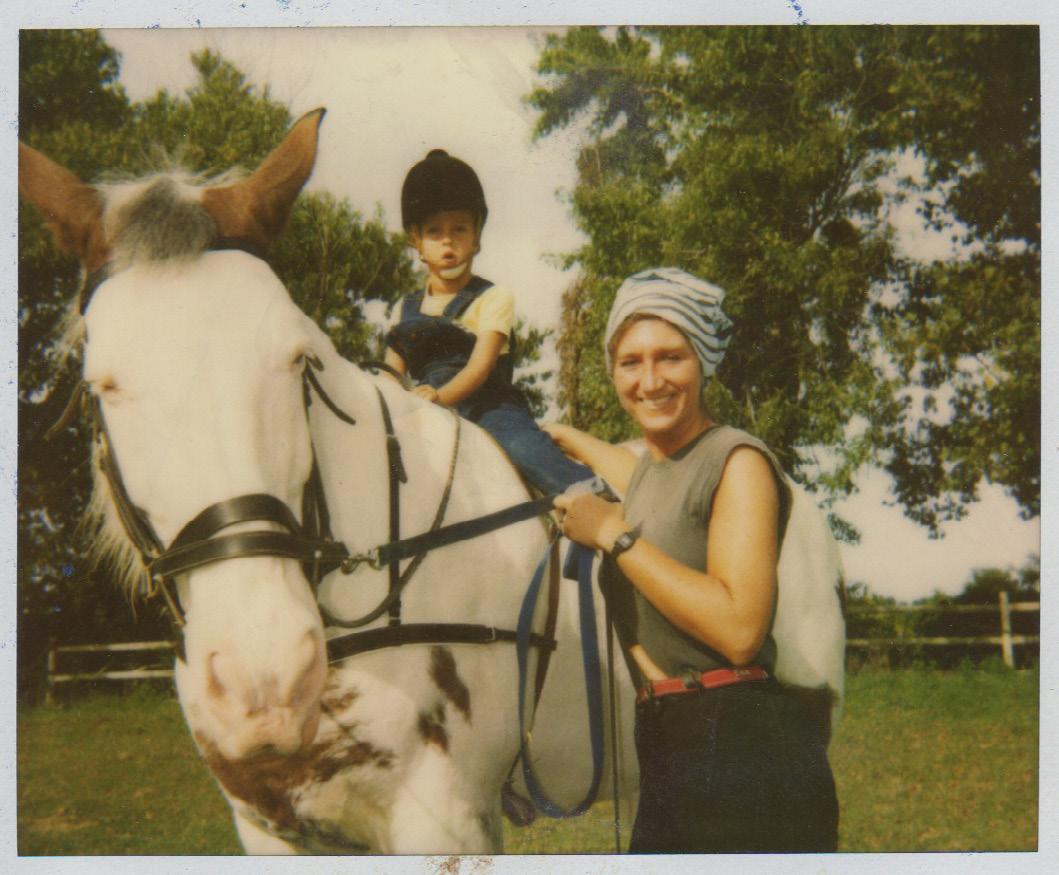

Sarah fell hard for horses, and her entry into the horse world was a bit unconventional, but no obstacles could keep her from them – not age, geography nor lack of tack. She’s a first-generation equestrian who grew up in Manhattan. When introduced to equines during her family’s weekend getaways to East Hampton, her first instructor wasn’t a trainer, but a horse-owning sculptor Sarah’s mother talked into teaching Sarah how to ride. There was no saddle small enough for a toddler that also fit the horse, so a homemade “saddle” was created from cloth with stirrup irons sewn on. Where there’s a will there’s a way.

Sarah and Guernsey; photo © Diana Zadarla

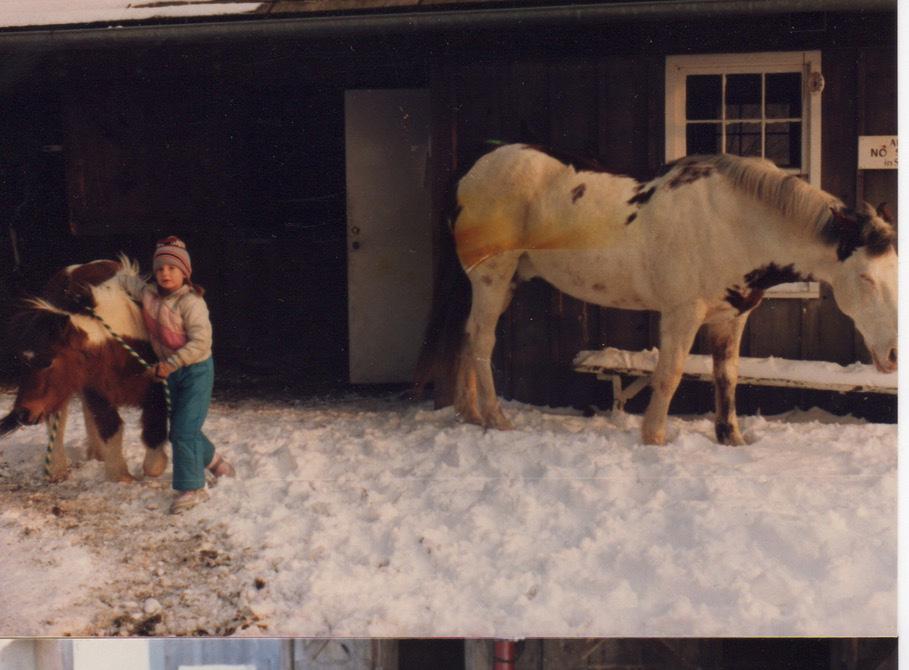

Sarah with Cutie and Guernsey

Guernsey

During her third riding lesson at age two, Guernsey, the sculptor/instructor’s pinto, lumbered into a canter, unintentionally unseating his young rider. As Sarah lay on the ground, the gelding circling at the end of the longe line leaped over her. In that one airborne stride, Guernsey both saved her life and perhaps foreshadowed her passion for jumping.

Sarah continued to ride Guernsey until she was old enough to attend pony camp and further her riding education – one that continues to this day. She currently rides with hunter/jumper trainer Leah Epstein at Ithilien Stables in Whitehouse, New Jersey.

Sarah, a self-proclaimed “hunter princess,” both loves and loathes the discipline. “It’s unperfectable, which is just beyond infuriating. Half a skipped lead change, a slightly close distance, and you’re just out of the running. . . But when you get that feeling, when you get those eight jumps straight out of a rhythm, and the moon and the sun and the stars align, and somehow you have a flawless hunter course, there’s no other feeling like it. And I think as a very driven person, that drive to perfect the unperfectable is what makes the hunter ring so compelling to me,” Sarah said.

Over the years Sarah has owned several horses that readers meet in Horse Crazy. Willow, a gray Thoroughbred mare Sarah owned when she was 17, is described as, “The seat of my highest equestrian glory and my lowest low.” During one of their earliest rides, while executing a flying lead change, Willow tripped and Sarah fell, breaking three vertebrae. She was told she could no longer ride. Six weeks later, while still in pain, Sarah entered the hunter ring of The Hampton Classic on Willow. The pair placed second in a class of sixty.

Sarah with Pulitzer (left) and Gold Standard (right); photo ©Erin O'Leary

Seventeen years later, Sarah’s heart horse Trendsetter, who launched her adult riding career, literally fell for her. During a canter-to-walk transition in a flat class, the bay KWPN gelding somehow caught a front hoof on the pristine arena footing. Sarah writes the two “locked stares” mid-fall. From the ground, Sarah knew his powerful haunches were plummeting in her direction – but they never made contact. Trendy flipped himself mid-air to avoid crushing her, and in doing so got caught on a half-barrel planter of flowers. He was essentially cast. Through the quick thinking on the part of her trainer Leah, a leadrope placed around his fetlock enabled the women to pull him to freedom. An onlooker approached Sarah and said she had never seen anything like it – the horse intentionally flipping himself the opposite direction of the rider – and that her horse saved her life, and she had better thank him. Thank him she did. Sarah’s gratitude for her horse is ongoing and today, at 21, Trendy is leased out, doing cross rail classes and living the horsey dream in South Carolina. A Breyer miniature of the gelding has taken up residence in Sarah’s home so she can always keep him close.

“It’s nice to have clients like Sarah who really love the horses that have brought them here, and have found a way to keep them and keep caring for them… Sarah has found really good leases for her horses. So they’ve been able to keep working at a lower level, but they’re really well cared for,” said Leah.

STORYTELLING IN THE BLOOD

Although equestrianism does not run in Sarah’s family, writing and the helping professions do. Sarah’s mother is a psychologist who has written self-help books and with Sarah’s late father, coauthored books on marriage. Sarah’s father, a Holocaust survivor and child psychiatrist, also wrote a memoir. His book, The Lost Childhood, chronicled the years he posed as a Polish Catholic to evade the Nazis.

Storytelling came naturally to Sarah even though she describes herself as borderline dyslexic and a terrible speller. She reads each article backwards from the bottom up in order to detect errors before submitting them for publication. In high school, Sarah got Cs and Ds in English the same year she got a perfect score on the English SAT.

“I love stories because I love people,” Sarah explained. “Nothing was going to stop me from telling stories. . . It’s just a compulsion to figure out the world, to crack it open and share it.”

Sarah said, “What’s great about my job is that every day is unbelievably different. Yesterday I was running around the horse country of Bedford, New York, chasing a llama that’s gone missing for a story. The week before, I’m writing harrowing stories about the virus and covering the presidency and it’s just a tremendously fascinating profession.”

Sarah and Trendsetter

Photo © Paws & Rewind

Early in Sarah’s career, she spent two years as a spa reporter, which she describes as an incredibly indulgent experience, but not how she was raised. “My father is a Holocaust survivor and my mother was abandoned at birth, and they basically sculpted their lives to help others heal from trauma. There’s a Jewish precept I write about in the book called tikun olam – healing the world. . . I realized that all of my healing was directed at sun damage on my own skin and that was a very blissful, but very meaningless life. I had to find a way to use my skills, which were journalism, for the good of someone other than Sarah.”

An opportunity to do just that presented itself when Sarah treated herself to a pedicure on her birthday several years ago. While making conversation with the woman painting her toenails, she was alarmed to discover the manicurist worked both the day and night shift of the 24-hour salon. The woman explained she slept in a barracks above the salon and would be awakened in the night if a customer came in for treatments. This disturbing conversation led Sarah to write a series of articles probing the dark underbelly of New York City’s nail salons. As a result of the articles, legislation was enacted to protect salon workers.

In 2018, Sarah’s reporting shined a light on dark secrets within the horse show world. Sarah interviewed 38 individuals affiliated with Flintridge Riding Club and wrote the New York Times Jimmy Williams exposé, which gave voice to the victims of the late show jumping trainer. In the wake of the Jimmy Williams article, Sarah began to explore the rumors surrounding George Morris and wrote another exposé.

Sarah’s empathy for survivors of physical assaults is deeply personal. In 2010, in her own apartment, Sarah was stabbed by an intruder. The chapter “Benediction” in which she details the crime and how horses aided her healing was not in the original manuscript. By initially leaving the painful memories out, it was as though she was subconsciously pretending it hadn’t happened. Sarah realized it was a part of her story and she was omitting the truth. According to Sarah, memoir, in order to be good, has to be true. She submitted “Benediction” late and the presses were stopped in order to include the chapter.

Sarah believes horses are an excellent model for recovery. “Seeing these prey creatures that somehow go around the world and go through their lives and are so bold for us, despite it being against everything in their fiber to be, really is inspiring.”

Leah, Sarah’s trainer and friend describes Sarah as dedicated. “Sarah is so invested in trying to make people’s lives better, whether that’s by telling stories that draw attention to injustice, or just loaning a friend her car because that person doesn’t have a car and they want to come take a riding lesson. I think that’s what drives her.” Just like her parents, in her own way, Sarah participates in healing the world – through her words.

RIDING, WRITING AND WHAT’S NEXT

Like many amateur riders with demanding careers, pursuing excellence in one’s work and in the saddle is a dance requiring flexibility. “I’m very passionate about journalism and I’m very passionate about horses. I have to have those things in my life to have a chance of feeling fulfilled,” she said. Sarah’s barn commute from her West Village home to Ithilien Stables is about an hour. She rides one day a week in the morning before work and then twice on weekends. “It’s very hard to be as good as I want to be, being a weekend warrior, but that’s taught me to cultivate other pleasures in riding.” Sarah cited a breakthrough in working on smooth downward transitions as an example of riding gratification.

“I bought an AO Hunter with a part of my book advance and my mom said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘Mom, the book isn’t called Horse Sane.’ So I’m always looking, looking at horses. A writer’s salary doesn’t really allow you herds of horses, but I am always looking for one to sort of fall through the cracks. One that’s a little discounted or has a funny story. I do have this little bit of a side hustle of leasing out horses, which funds my riding.”

Currently, Sarah is in talks with Hollywood to make Horse Crazy into a docuseries. She is also working on a “super secret” project with renowned horse trainer Monty Roberts.

One of the most thrilling effects of putting Horse Crazy into the world, according to Sarah, is that the information provided has powered conversations of inclusion in the equestrian world. Sarah devotes a portion of Horse Crazy to the erased legacy of Black cowboys from the pioneer era – one in four cowboys were in fact Black, though they have often been excluded by racism from the historical record. “Black riders have always been there. They’re not new just because you saw them riding through Compton in a protest march. They’ve always been part of the story and they’ve been totally marginalized in our sport. There need to be dramatic steps taken to increase inclusion in the sport… Horses are deeply democratic, you know. As the great horse whisperer Monty Roberts says, ‘They only demand one thing: that you’re their safe place to be. Horses don’t care who you are, they care how you are.’ That to me means that they’re for everyone,” said Sarah.

And that is the essence of Horse Crazy: horses are for everyone, gifts to us all.