22 minute read

Fine Time

The Isle of Man, in the middle of the Irish Sea, a similar distance from the coasts of both Northern Ireland and England, seems an unlikely destination in the world of watchmaking. We’re used to hearing about the latest models from the Vallée des Joux in Switzerland, but not so much an island of 84,000 people, best known for its rural landscape and medieval castles, and the annual Isle of Man TT motorcycle race. However, there is a self-contained watch manufacturer here, Roger W Smith, with a skilled workforce of just 15 people, taking delivery of raw materials, creating and shaping every component, and producing a mere 17 examples each year. The target customer is the ultimate watch connoisseur, who appreciates the intricate details and precision of the craft, and is not swayed by high prices or lengthy waiting times (currently six years).

Managing to secure an order for a Roger W Smith watch is an achievement in itself, with those who refuse to wait looking to see if any crop up at auction — in November 2022, a Series 1 model sold for £660,000 ($795,000) in an online sale organised by A Collected Man, a London-based watch-trading specialist; and a year earlier, another Series 1 raised a similar amount in an auction held by Phillips.

Advertisement

W hat does the man at the top of the company, founder Roger W Smith himself, think about the resale market for his product causing such a stir?

“It’s hugely gratifying, but throughout all of this it’s never really been about the money for me, just the craft,” he says, speaking from his Isle of Man offices. “To see these watches in demand like that, it’s incredible, and it’s a side to it that really amazes me.”

Born in 1970, in Bolton, Smith’s early interest in watches led to him taking a course at the Master School of Horology in Manchester, which he passed top of his class with honours from the British Horological Institute. A visiting speaker, legendary British watchmaker George Daniels, who lived on the Isle of Man, was impressed with Smith’s work, and invited him over to work on a new series. Smith soon started working on his own watches too, and when he died in 2011, Daniels left his entire workshop to Smith to help him.

F rom there, Roger W Smith grew into the company it is today.

“We have 10 watchmakers at the benches, building each model from scratch, including the cases and the movements,” Smith explains. “I oversee the process these days, rather than get too involved, and for me it’s good to keep on passing down these skills. The watchmakers who have been here the longest are now training the younger generation.

“And we use a lot of traditional tools, here in the George Daniels workshop. There are devices to make components by hand, but also state-of-the-art CNC equipment. The engine-turning machine we use to apply the patterns to the dials is well over 100 years old!”

Just what you need when turning out 17 watches per year. “We have aspirations to get up to 24 in the not-so-distant future,” Smith admits. “There are five different models that we offer currently, from the Series 1, which is our entry level with its simple time-only movement, right up to the Series 5 Open Dial. The Series 2 has a power reserve indicator; Series 3 has a calendar complication; and Series 4 is an intricate triple calendar wristwatch.

“But we never carry stock, and each watch takes about 11 months, start to finish, sold directly to the client. It’s a different business model compared to other watch companies, but it works for us. This becomes a personal journey for the customer, as they like to be involved, visit the workshops, and get to know the people building their watch for them.

And I still get a huge amount of pleasure from seeing these pieces being built.”

Smith is a champion of British watchmaking, but also manufacturing in general. He was awarded an OBE in 2018, and is the chairman of the Alliance of British Watch and Clock Makers, which has 75 members, representing lots of different businesses. In 2015, he was the subject of a documentary, The Watchmaker’s Apprentice, which explored his relationship with Daniels. Smith also has an ongoing relationship with Birmingham City University, hosting undergraduate horology students within the workshops.

So what does the future hold? “There are still watches I want to make,” Smith concludes. “I always thought 10 would be a good number for a body of work, so I still have more to do. The Series 6 I started designing in lockdown, and the mechanism for that will be produced soon. Plus we’re always improving and refining everything we’re already doing. Even the work of George Daniels, his escapement, we’re still developing it, though we’ve been using it since 2006. It’s about trying to improve mechanical timekeeping, and making it relevant for today’s digital world.”

As he prepares for this month’s Academy Awards, Bill Nighy talks notoriety, loafing around, and those Anna Wintour romance rumours

WORDS: ED CUMMING

Bill Nighy sits down, dressed in a full Crystal Palace kit and running a hand over his recently shaven head. “Let’s talk about my sexy life,” he says loudly, furiously chewing gum, before snapping his fingers and summoning a pint of lager. Not really. Other actors change their look or their approach. They have phases. Bill Nighy has been playing Bill Nighy to glorious effect for nearly 50 years. He is not about to stop now. He glides into a café he has chosen — he likes choosing cafés — around the corner from his home in Pimlico, London. He offers a couple of fingers to shake, the others clenched by his Dupuytren’s contracture, a condition he has suffered from since his 20s, before politely suggesting we move to his preferred table. He has many preferred tables.

He is tall and angular, his grey hair swept neatly back. In a development that will not surprise keen Nighy observers, he is wearing a suit. Today it is a beautifully tailored charcoal number over a navy shirt made of wool that looks so soft you want to stroke it. His eyes sit behind thick-rimmed glasses. There is a copy of the London Review of Books under his arm.

Nighy has always dressed older than his years, so at 72 he looks just as he always has: like a cool older dude.

Even if you didn’t know who he was, and the ripple of attention from other customers as he arrives suggests they do know who he is, you would understand that he was someone interesting, the guy in the corner of the jazz club with some wonderful stories that may or may not be true. He is a bit tired, he explains. He has just flown in from the Toronto International Film Festival. Before that he was at Telluride, in Colorado. He finds it difficult to sleep on planes; difficult to sleep in general.

“I’m not famous for it,” he says, in that deep, measured voice of his. Luckily he is famous for plenty of other things. Famous for his breakthrough BBC miniseries, The Men’s Room, in 1991. Famous for a handful of brilliant plays, like Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia and Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange. Famous for avoiding Shakespeare because he ‘can’t act in those trousers’. Extremely famous for his performance as the ageing rock star Billy Mack in 2003’s Love Actually, a role that changed his career. Famous, and well paid, for his turn in Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean films as Davy Jones, a villain whose face is squid. Famous for his love of Crystal Palace.

The exhausting recent schedule has been in the service of his latest film, Living, which might be the best he has ever made. And for which he will contend the award for Best Actor at this month’s Academy Awards, the first time he has been nominated for an Oscar.

The script is by the Nobel Prizewinning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, and the lead part was written with Nighy in mind. It came about after a dinner he had with Ishiguro and his wife Lorna MacDougall, and the producer Stephen Woolley and his wife and business partner Elizabeth Karlsen.

“What is my life like?” Nighy says, acknowledging the good fortune of having one of the great novelists of his generation craft a part for him. “You feel you must have been pretty good in a previous life. It was wonderful that Mr Ishiguro — I’m encouraged to call him ‘Ish’ but I can’t bring myself to — wanted to write it with me in mind. I was very moved by it, because it was the first job I did after Covid. It was great to be back at work, surrounded by people.”

For his part, Ishiguro says writing with Nighy in mind “made things much easier,” and that even the character’s name, Williams, was derived from the actor’s own.

“I have admired Bill Nighy hugely for many years, and found it frustrating that he was most often to be found in brilliant supporting roles, but rarely as the central figure in a film,” he says. “He is one of those rare actors who can arouse deep affection in a viewer without resorting to sentimentality or manipulation. Prior to Living, I’d become convinced he was one of today’s genuinely great screen actors, who’d curiously achieved, in the UK, the status of national treasure without ever having a major starring role worthy of his giant talent.

“In Living I think Bill gives not only one of the greatest screen performances of recent years, but a kind of great performance that is uniquely his own,” he adds. “It’s one of those massive performances that seems to come from something deeper than superb technique.”

Living is set in 1953, in London. Nighy plays Mr Williams, a buttoned-up civil servant who has never recovered from the death of his wife 20 years ago. He lives in the suburbs with his grown-up son and daughter-in-law. Every day he takes the train to work, where he presides over an office of dull men in suits and a secretary, Margaret (Aimee Lou Wood). Early on in the film Mr Williams receives a cancer diagnosis. Re-evaluating his life, he forms a friendship with the much younger Margaret that helps to change his outlook. His remaining months acquire fresh purpose. He resolves to use his position to build a playground for children in a bombed-out edge of London.

In a crucial central scene, Mr Williams tells Margaret that all he wanted to be was a gentleman. You can imagine Nighy saying it himself.

“I’m interested in what’s called Englishness, particularly of that period, which is a certain restraint and reserve,” he says.

“Modest behaviour. It’s usually spoken of in a slightly negative way, in terms of suppression. But also it’s kind of admirable. From an acting point of view it’s enjoyable to try and express quite a lot with not very much.” As to whether he has succeeded, he’ll have to take our word for it. Nighy, who never watches his own work, has not seen Living

Like Mr Williams, Nighy grew up in the suburbs — in Caterham, Surrey, with an older brother and sister. His father, Alfred, managed a garage; his mother, Catherine, was a psychiatric nurse. In recreating a world so close to his childhood, did he find himself cast back?

“I did, yeah,” he says. “I was poor. I would have been one of those kids

[for whom the playground in the film is intended]. It’s odd when you get to an age that black-and-white footage involves you. I wasn’t doing my dad as Mr Williams. But my dad was a very decent man, and reserved in the way people were in those days. He was a principled man.”

Acting has only ever been part of the Nighy equation, an occasional distraction from the serious business of living well. As much as any of his roles, Nighy is famous for being Bill Nighy, gentleman at large. Ask anyone who spends time in central London and they will have seen Bill out and about.

When the Queen died, it was suggested she had been seen in real life more than anyone else, but Nighy must be close.

When I polled Twitter for sightings, I received more than 800 replies. Bill drinking coffee at Lina Stores in Soho, Bill walking in and out of The Wolseley, Bill wandering the V&A, Bill having a frozen yogurt from a shop called Snog, Bill wandering the Royal Academy, Bill browsing books in Hatchards, Bill sitting at the bar of the Royal Opera House, Bill sitting at the bar of the Stafford hotel, Bill flirting with a barmaid, Bill browsing cravats in Liberty, Bill drinking coffee in Hampstead with Nicole Farhi, Bill ambling down Piccadilly with Anna Wintour (more on the Vogue editor later). The man is never at home.

In these tales, the same words crop up again and again. Dapper. Immaculate. Sharp. Unfailingly, the people who have seen him recall a well-cut figure, all silk scarves, trench coats and tightly furled umbrellas. Any reported interactions are charming. Bill will have a chat. Bill will stop for a photo. Bill will wave back. A certain dream of London, a place where perfectly dressed gentlemen stroll about eating, reading and looking at art, seems possible when Nighy is around. This level of scrutiny would make other people uneasy, but Nighy long ago came to terms with the idea that a few selfies was an acceptable price for his freedom.

“The thing is I don’t own a car and have no interest in owning one,” he says. “It’s an odd thing being an actor, you forget [that you are recognised]. But I love cafés as much as I love anything. It’s pretty much my reward for everything. So if I can’t wander about and go to cafés, then it’s all a bit…” He trails off.

“I’m not going to get mobbed in the street. I have a degree of notoriety, which is just about right. People are friendly, but it’s not a frenzy. I manage pretty well.”

He didn’t come straight to acting. The original plan was to be a writer. When he was 16, he moved to Paris to try to emulate his heroes Hemingway and Fitzgerald. He didn’t write anything, but he assumed some of the lifestyle.

Eventually, he returned to study at Guildford School of Acting — not Guildhall, although he enjoyed the occasional confusion — before starting his professional career at the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool.

He doesn’t read the papers or watch the news. We speak a few days after the Queen has died. He says his thoughts are with her family. He wore one of the then Prince Charles’s suits once, “midnight blue, a serious piece of tailoring.” You get the sense that whatever he is talking about, he would almost always rather be discussing clothes. He has previously railed against the trend for what he calls “bogus sportswear”, although he has admitted to wearing trainers for exercise, which he took up only in middle age.

“I do think [fashion] has been a bit downhill since 1947. If you took people off the street in 1947, they’d all look kind of OK. It wouldn’t matter what shape you were. I don’t know if that’s true today.”

He reads avidly. He recently read all of Joan Didion, whom he adores. But the most animated he becomes is when he talks about the science-fiction writers William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, both of whom he admires.

“[Gibson] is witty, dry, hip, imaginative,” he says, a sequence of adjectives that might be applied to Nighy. “There’s something about the atmosphere of his books I really like.

“I’m good at not working,” he adds. “I love loafing around. They used to say [of acting] that there would be periods of unemployment and my heart used to sing. The whole idea was not to go to work. There was something glamorous about not working. It’s like when you used to play truant. When everyone else is at school and you’re not, it’s very exciting.”

There are moments when Nighy’s leonine sangfroid slips, ever so slightly. As he talks he slides his phone twitchily around the table, as though looking for somewhere it feels right, before sweeping it on to the banquette beside him in mild frustration. He stopped drinking decades ago, perhaps not coincidentally around the time his career took off. It doesn’t seem like a stretch to imagine that some of his other habits might have replaced booze. For all his visibility, parts of him remain out of sight.

“People think I’m laid-back or mellow, words like that, which is not how I experience my day,” he says.

“I’m just as wired as everyone else. People mistake me for someone who’s relaxed. I am sometimes, but other times it’s just a trick of the light.”

Routine is part of his mechanism for coping with the stresses of work.

“I like to get up an hour and a half before I have to be anywhere, so I can go to a café, take a book. I like to eat before I get anywhere. I don’t want to eat when I get there. When I get into a new trailer at work I get the coffee machine going and put certain tunes on, just to control the environment.”

For all the time he spends in restaurants, his frame suggests he doesn’t eat much. “People think that, but actually I eat quite a lot,” he says. He had been eating salmon for breakfast every day but had to stop. “I hit a wall with salmon,” he says. He currently favours a Parmesan, mushroom and tomato omelette, with avocado on the side.

One obscured area is Nighy’s private life. For 27 years his partner was actor Diana Quick. Their daughter, Mary, 38, is a director and has two children of her own; he says he is prone to spoiling his grandchildren. Though they broke up about 15 years ago, he and Quick remain close. When he says that if he received a diagnosis like Mr Williams’s, he would spend more time with his family, it is still Diana and Mary he means. I have to ask about Wintour, I say. They have been photographed together many times.

“I’d love to answer that,” he says, leaning towards the Dictaphone. “But if I did, I’d be involving the readers in something very close to gossip, and I know they’d never forgive me for that.”

It’s a very Nighy answer: charming but evasive. He’s also used it before.

We walk out into Pimlico’s afternoon sunshine. For once, Nighy has turned for home — there is football to be watched — when he is interrupted by a young man who comes bounding out of the café and introduces himself. He wants to be an actor, he says. Does Bill have any tips? He is thinking of doing a master’s at Lamda. Is that a good idea?

“I don’t know what a post-grad is, but then I don’t really know what a grad is…” Nighy jokes, before offering a more serious reflection. There’s only so far talking can take you, he concludes, “before it comes down to experience.”

The young man quotes a line from About Time. Nighy talks about the trick of making it seem like you’ve just thought of the line.

“Acting’s not rocket science, but it’s not nothing, either,” he says. “It’s an honourable thing to be involved with.”

“Fashion design is still a male dominated world — even though a lot of them are designing for women,” says Iris van Herpen, the visionary Dutch haute couturier.

Y ou may not recoginse her by face, but would be hard pushed to forget seeing her work. Her name is synonymous with extra-terrestrial, three-dimensional gowns that appear to shape shift in motion, the best of which possess such perplexing levels of intricacy the eyes can only gawk.

F or this reason, Herpen, 38, is a red carpet virtuoso, both adored and championed by the world’s most outlandish dressers — from Björk to Lady Gaga, Winnie Harlow, Gwendoline Christie and Cara Delevingne. The sculptural designs are often regarded as fine art, collected by prestigious museums including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the V&A, and she has been a fixture of Paris’ couture week since joining the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in 2011.

A fter more than a decade spent in fashion’s most exclusive sector, Herpen remains discontent with the diversity on schedule. This season 29 maisons showed; 22 collections designed by men, and seven by women.

“ My team is really female driven. It’s important to me, and it’s important to talk about it and show it is possible. I hope to be an example for others,” she says via video from Amsterdam. It is 9am there, and she looks ethereal in a chinoiserie style robe with tumbling curls.

M isogyny was the catalyst for her offering during couture week; a short film referencing the global female struggle, and a direct response to the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran. “It’s an artistic expression of a political movement,” Herpen says.

T he collection is titled Carte Blanche and was shot by French artist Julie Gautier underwater. This is a successful pairing — the nature inspired and technologically derived gowns look like deep water corals as models hold their breath and contort.

“ We chose to do it underwater as a symbol for women having no speech, with this extremely heavy underwater dancing,” Herpen says.

To conclude, a woman lets out a scream of air bubbles and floats to the surface. “It is a dedication to the strength that is needed to speak up,” she explains. It is visually rich, and makes for suffocating viewing.

D eciding to show with a four-minute film bucked the trend across the other couturiers who, post-pandemic, doubled down on the flamboyance of runway spectacles. For haute couture, Franck Sorbier was the only other designer to opt for digital.

T he risk proved a very real one when Herpen released the onschedule film just two hours after the Schiaparelli show, where Irina Shayk walked the catwalk in the same lion head gown Kylie Jenner wore on the front row. Nearby, Doja Cat sat with her face covered by 30,000 red Swarovski crystals. A social media eclipse ensued, and Herpen’s collection struggled to make a noise.

W hy snub the catwalk? “Freedom of expression. In the last few years we’ve spoken a lot about more flexibility in how we present our work, but everything has gone back to the old ways,” she says. “The system is still drawn to the traditional, but it’s important to have different options when presenting collections.”

I t is a quiet approach. The artist in Herpen stands for integrity first and foremost — this season that has come with a cost. “The subject [of the collection] is an important and heavy one. It needed the storyline and telling of a film. It was the only way to embody the emotion that I wanted to visualise,” she says.

H er resolve comes as no surprise. Herpen has long been a black sheep in couture, and since founding her label in 2007, has maintained an unrivalled grip on her entire company output. She does not produce ready-to-wear, “so there is no intermedium of stores or buyers that tell me what to do,” she says, and proudly runs her atelier without the need for a secretary. That is remarkable given her output, which last year included a custom costume for Letitia Wright in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever , a Vogue cover with Michelle Yeoh, Björk music videos and Lorde concerts, to list a few of her personal highlights. She is also two years into creating a vast 12 room retrospective exhibition at Paris’ renowned Musée des Arts Décoratifs, set to open

November 29, 2023 – “that really feels like a life’s work,” she says, content.

A nd these are only her physical creations. “The last year for me has been quite focussed on augmented reality,” Herpen says. She has found herself near the forefront of Web3 fashion, in most part thanks to design process beginning with digital rendering. It makes sense, too. Innovation has been her USP since TIME Magazine named her 3D printed dress one of the 2011’s 50 Best Inventions.

D o not hold your breath for the results — she is waiting until tech platforms can cater to the detail of her physical outputs. At present, attempts at Metaverse fashion weeks, hosted on platforms including Roloblox and Decentraland, have been defined by comically rudimentary avatars.

“ Creatively, the sky is the limit in terms of what will be possible,” Herpen says. “But it stupidly depends on what the bigger tech companies come up with. I do believe augmented reality will be an added layer to our physical reality, in all aspects of our lives — creatively, politically, economically. Everything.”

I t throws up endless questions. Digital fashion’s appeal is democratisation, but how do you balance this with haute couture pricing? What degree of resources should you funnel into a space that is in constant development, and how do you protect your intellectual property when laws lag behind advancements?

“ I have no idea,” Herpen says. “But we are in an AI revolution at the moment, and more will come quite soon. That I know for sure.”

A new book reveals the origins of Parisian fashion house Lanvin, and how its founder, Jeanne Lanvin, is still inspiring haute couture today

WORDS: CHRIS ANDERSON

With creative director Bruno Sialelli at the helm, Lanvin appears to have a bright future ahead of it. Appointed in January 2019 to update the oldest French fashion house in existence, Sialelli scored an immediate hit with his Curb sneakers, and their exaggerated, lace-heavy appearance. The late Louis Vuitton designer Virgil Abloh became a fan, as did hip-hop artist Kid Codi, and Dune actor Timothée Chalamet, who bought pairs in multiple colours. Suddenly, after several tumultuous years, where the brand seemed to work its way through one creative director after another, desperate to find its identity, Lanvin was seen again as a cutting-edge, sought-after name. People were even singing about it — check out rapper Billie Essco’s track, ‘Lanvin Skate Shoes’.

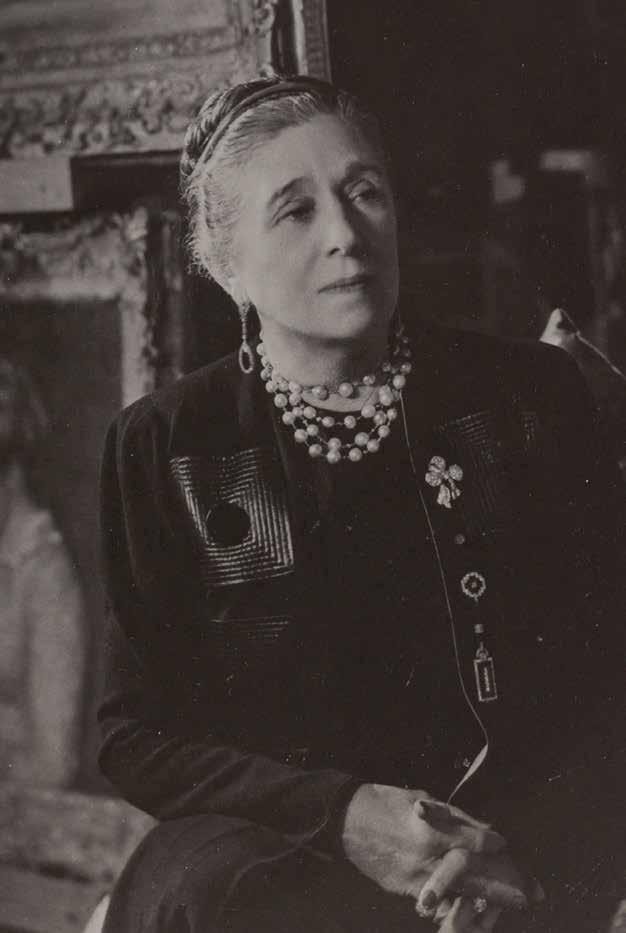

The hype now surrounding the house mirrors that of its early days, when Jeanne Lanvin herself attracted the attentions of the rich and famous in Paris with her creations, including hats, dresses, children’s clothing and perfume, encouraging her to open her own boutique in 1889 and supply these customers full time. Today, Lanvin is 134 years old — no French fashion house has been in business longer — with Vogue magazine saying of its founder in 1927: “Truly, she is one of the great women of the world.”

Jeanne Lanvin, her personal story, and the origins of the brand bearing her name, are the subject of a new book, Jeanne Lanvin: Fashion Pioneer, written by Pierre Toromanoff, published by teNeues in English and German. It features old photos, paintings, and images of classic dresses, sourced from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, or the Palais Galliera museum in Paris, where much of her work is now on display. Expressing his own admiration for his muse, the author, Toromanoff, says, “Jeanne Lanvin is to haute couture and fragrances what Leonardo da Vinci is to painting and science.”

The book is largely biographical, following Jeanne Lanvin from her birth on January 1, 1867 to her death at age 79 on June 6, 1946. We learn how she was the eldest of 11 children, growing up in one of the poorer areas of Paris, and discover how becoming an apprentice milliner at age 13, making fanciful hats, would kick-start her interests in fashion. “In Paris alone, more than 650 milliners were established at the beginning of the 20th century,” explains Toromanoff, such was the popularity of hats among men and women at the time. “One of Jeanne’s frequent tasks was to deliver new hats to clients, and this allowed her to discover the most fashionable neighbourhoods of Paris.”

Making a name for herself, Jeanne Lanvin was able to establish her own milliner’s shop in 1889. Then, four years later, she moved to a larger boutique at 22 Rue du Faubourg SaintHonor é , and over the years would proceed to take over the entire building. An address still associated with Lanvin today, the location was thoroughly refurbished and given new life in 2021 by Belgian designer Axel Vervoordt, who wanted to match the modernity of Bruno Sialelli with the heritage of Jeanne Lanvin. There are Burgundy stone floors, rounded lines and swirls, and a number of original features, such as the Printz triptych mirror, in Jeanne Lanvin’s office since 1930, and the black lacquered elevator, with carved wooden panels and gold leaf.

A short-lived marriage to Count Emilio di Pietro, an Italian nobleman, resulted in Jeanne Lanvin giving birth to her only child in 1897 — her daughter, Marguerite Marie Blanche di Pietro, which as Toromanoff describes, “would largely determine the evolution of the Lanvin brand in the years to come.” It was by making clothes and hats for Marguerite, often matching her own, with luxurious materials and intricate weaves, that she gained the admiration of Parisian high society, who wanted similar outfits for their own children, leading to Jeanne Lanvin opening a children’s clothing department at her store in 1908.

Just one year later, orders for children’s clothing were exceeding those for hats, and clothing for young women also became part of the offering, so that mother and daughter could shop and choose outfits together. Each look was fresh, surprising and magnificent. “Her only aim was to magnify women,” says Toromanoff. “Jeanne Lanvin transformed fashion without seeking to revolutionise it.”

The Lanvin empire continued to expand through the decades.

Jeanne Lanvin opened a dye factory in Nanterre, so she could establish her own shades: the famous Lanvin Blue, and Polignac Pink as another tribute to her daughter. Ribbons, pearls, embroideries and precious details became the trademark of her dresses, now available worldwide, and worn by nobility and Hollywood actresses. “Jeanne Lanvin was skilled at instinctively assimilating and reinterpreting the most diverse influences and motifs, from Aztec patterns to Slavic embroidery,” Toromanoff says of the quality of her work.

After becoming the first designer to launch a children’s fashion line, Lanvin followed it with the first made-to-measure collection for men in 1926, and teamed with architectdecorator Armand-Albert Rateau to offer furniture, rugs, curtains, stained glass and wallpaper in the Art Deco style. Lanvin Perfumes was the next step, with My Sin developed for the US market, and then Arpège formulated in 1927 to celebrate her daughter’s 30th birthday — once again, Marguerite had inspired a new direction for the company. “Nothing seemed impossible to Jeanne Lanvin,” Toromanoff says of her determined spirit.

Upon the death of her mother in 1946, Marguerite inherited the business, overseeing it until her own demise in 1958, at which point ownership transferred to a cousin, Yves Lanvin. Various owners, including L’Oréal, have helped to shape the brand in the decades since, with the current proprietors renaming themselves the Lanvin Group in 2021 and appointing Bruno Sialelli as creative director. What Jeanne Lanvin might have thought of his Curb sneakers is anyone’s guess, but a read of this new book can perhaps provide a few clues.

As Toromanoff himself concludes, “This is the tale of a woman who overcame adversity and social determinism, demonstrated formidable business acumen, and defied the conventions of the time to live as she saw fit. She serves as an example and inspiration to all women.”