8 minute read

Coopeguanacaste brought electricity to Tamarindo in 1974. Before that, there simply wasn’t any.

TRAVEL & ADVENTURE Tamarindo Pop Quiz

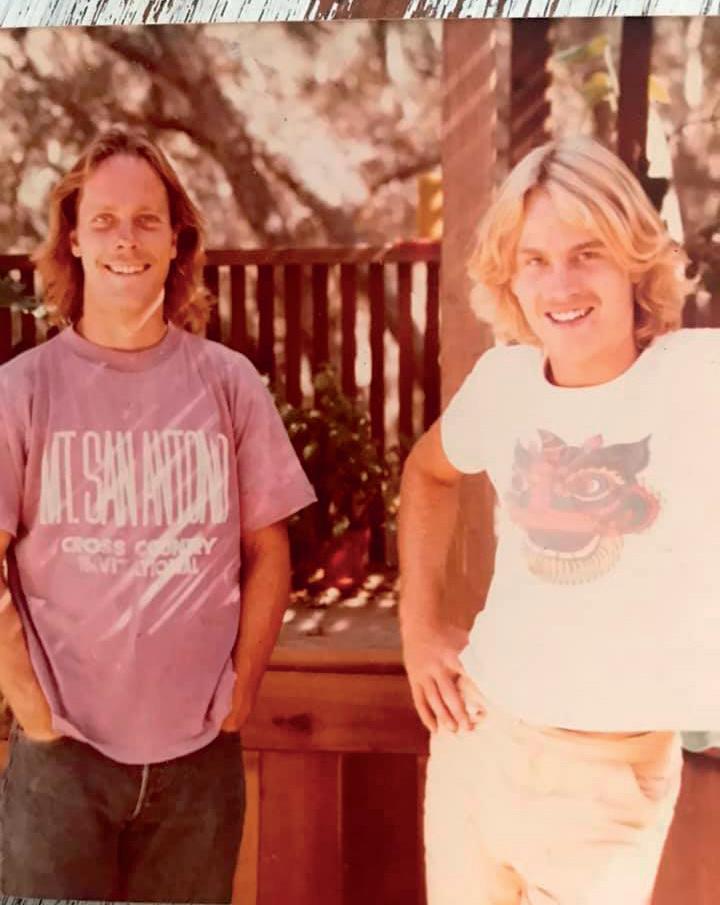

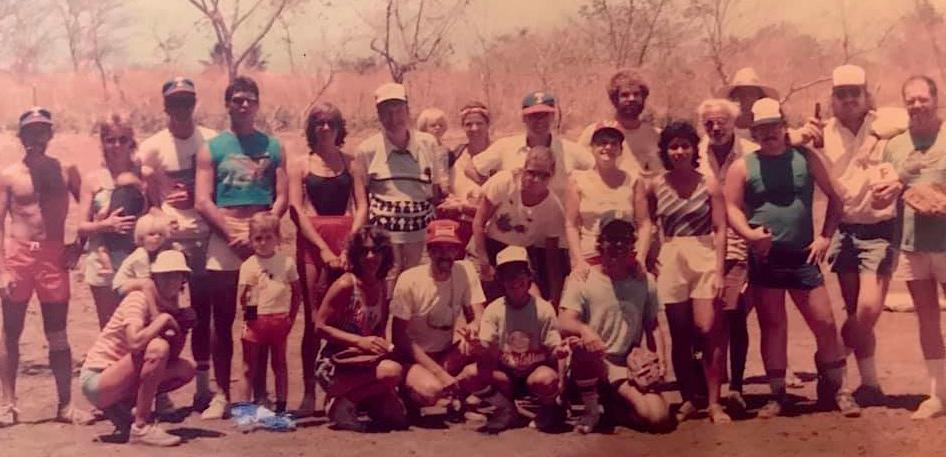

By Jim Parisi & Alei Burns Photos courtesy of Valerie Townley

Advertisement

“T ouristy” might be most people’s swift, no-brainer response if “Tamarindo” came up in a word association game. They might find it hard to believe how recently this description came to fit what is now one of Costa Rica’s most popular Pacific beach towns.

In fact, it was barely a generation ago that 1. Coopeguanacaste brought electricity to Tamarindo was getting ready to make its mark on Tamarindo in 1974. Before that, there simply the map as such. The same goes for the surrounding wasn’t any. Guanacaste province as a preferred destination for travelers. Tamarindo had been a fishing village for literally centuries, well before Guanacaste annexed itself to Costa Rica in 1824. That may be common knowledge for many local people living here. But for relative newcomers, visitors and others unaware, we offer these “modern” Tamarindo tidbits of history that may seem surprising. 2. The rural aqueduct of Playa Tamarindo was constructed three years later, in 1977, through a combined effort by Instituto Costarricense de Acueductos y Alcantarillados (AyA) and Tamarindo residents. Before that, wells went dry and became salty before the start of a new rainy season. Water was at a premium, even more so back then.

3. Telephone lines did not arrive until 1996. Then came payphones and people waiting in line to use them when in service, which was sporadic at best.

We appreciate the vintage photos she made available to share with Howler readers.

Into the early and mid-1970s, the PanAmerican Highway from the Nicaragua border all the way to Puntarenas was merely a gravel road. The dirt road leading into Tamarindo washed out during rainy season, so anyone wanting to leave had to walk to Villarreal to catch a bus. The only flights from the U.S. to Costa Rica in 1970 were provided by Pan Am Airlines and flew to San José on a less-than-consistent basis. This is why so many people drove to Tamarindo, in vehicles that they could sleep in. Blocks of ice were delivered by truck on Thursdays and could be counted on being puddles of semi-cold water by Sunday morning. The first cabinas for visitors were built in 1965 8. and were rented almost exclusively by Ticos from Santa Cruz or San José. Hotel Tamarindo Diria was constructed in 1973 with the intention of catering to international travelers who were initially fishermen, not surfers, looking to catch marlin and sailfish off the coast. Papagayo Excursions began at about the same time in response to this influx of outside anglers. It is no secret that Playa Tamarindo has become a mecca for surfers of all levels due initially to the two “Endless Summer” movies by surfer-filmmaker Bruce Brown. His close friend Robert August was one of the surfers featured in the original 1964 movie, and the reason Brown came to Tamarindo to film on location in the sequel nearly 30 years later.

August tells the story of meeting the late Russell Wenrich, an early developer here, at the 1990 Surf Expo in Orlando, Florida. Having touted Tamarindo on that occasion as the ideal surf spot, Wenrich later paid the airfare for August and a group of fellow surfers and filmmakers (including Brown and Robert “Wingnut” Weaver) to come visit. He even put them up for free in his cabinas because Wenrich saw the future potential of Tamarindo becoming a surfing destination point. The result was “Endless Summer II”. Russell was a visionary, to say the least. 9. Playa Tamarindo is bordered to the north and to the south by mangrove estuaries, the largest of this kind in Latin America. They play host to more than 175 species of birds, including crowned herons, egrets, white ibises and roseate spoonbills. 10. To the north, Las Baulas National Marine Park is home to the endangered leatherback (baula) turtle. More than 800 female adult turtles come to lay their eggs here as they make a slow, perilous comeback toward survival of their species. The female, which can weigh up to 1,500 pounds, lives in the ocean for 13 years before returning for the first time to lay her eggs (which can number up to 120) at the same location where she was born.

And there are your fast and fun facts and minutiae trivia about Tamarindo for today. I hope you learned something at least a little interesting in this article, which would not have been possible without the help of Christina Spilsbury and Robert August. Thanks, guys.

What a Ride!

By David Mills

(Original Howler publication date: January/February 2020)

Having been kindly asked to write this guest editorial, I invite Howler readers to join me on a trip down memory lane to 1996. From my vantage point as retired co-founder of the magazine, we’ll look back on an incredible journey that was launched from a bumpy but unshakeable start.

Nearing closer to the quarter-century milestone is no small longevity feat anywhere, especially in Costa Rica where businesses can rise and fail in a very short time. And if that is still a reality for many entrepreneurs here nowadays, try to imagine the obstacles they would have faced barely a century ago when Guanacaste remained a barely pioneered new frontier.

Roughing it

Road conditions were notoriously dreadful. Today’s short trek from Tamarindo to Villarreal took half an hour on the pitted lastre road (Costa Rica's renowned gravel and dirt road surfacing material). Driving on to Santa Cruz would take another 90 minutes.

There was no bank within miles of Tamarindo, but there were travelling tellers who made a weekly bus trip to town and parked in The Circle. You lined up on the left side and handed in your dollars to a teller who wrote down the serial numbers of each one. Then you went to the right side of the bus where another teller recorded the serial numbers of the colones you received in exchange.

There were no phones in town, except one for public use at a Tamarindo restaurant in The Circle. You gave the number you were calling to the attendant who dialed it. When your party answered, she handed you the phone and hit a stopwatch. At the end of the call she charged you so much per minute. There was another public phone at Las Palmeras in the main street that also offered a fax service.

In a moment of lunacy, my friend, Lee, and I decided to publish a magazine to inform readers about local happenings. The first edition was an eight-pager — two double-sided wide sheets stapled in the centerfold.

Buses and bikes

The Liberia print shop we chose to produce 500 copies told us the job would take a few days. Not having a car, we relied on buses that made only one round trip daily from Tamarindo, three hours each way. Arriving at the printer on a Thursday to pick up our magazines, I was assured they were “almost ready.” What awaited inside was chaos, with hundreds of loose sheets strewn around. The twostep manual collating process required one muchacho to punch the staples through the center of each unfolded pair of sheets and his co-worker to flatten them in folded place with a screwdriver.

Seeing no chance of the task being finished without missing our return bus departure, we grabbed all the finished magazines and the loose sheets, plus the stapler, and dashed off. At home, we finished stapling the 500 magazines before proudly distributing them around Tamarindo, Flamingo and Potrero on our bicycles. The road from Huacas to Flamingo was all lastre so it was strenuous work.

For the Howler’s second monthly issue we found a small firm in Santa Cruz to print 1,000 copies. All seemed fine until our return bus trip from picking up the finished magazines. We discovered too late that rainwater during a torrential downpour en route had leaked through a bus floor hole where our backpack full of magazines had been placed. All our Howlers were soaked! We hung them on a clothesline to dry, which took a couple of days.

Our sole reliance on bike transportation served us well during month three. With no threat of rain, we cycled to Santa Cruz, dropped off the magazine content file on a disk and cycled back three days later to pick up the printed copies. The all-lastre road between Tamarindo and Santa Cruz gave us a great workout, which continued during the days we spent distributing the magazine by bike.

Our publishing venture then took some turns for a different kind of worse when we started sending each magazine disk to a printing service in Cartago. Not only did this printer always fail to ever deliver the magazine on time, but was nothing short of a liar.

One month he told me,“We printed it on time, but we had a break-in.”

“What?” I said, “they stole all the Howlers?”

“No, Don David,” he replied. “But they broke in through the roof and it rained overnight, and guess what was sitting under the hole? The Howler … it was ruined.”

I called back a couple of days later to see how the reprint was going, asking the receptionist, “Any news on the break-in?”

“What break-in?” she answered.

Well, the words ”give up” do not figure in my vocabulary, so I persisted in finding a great printer, Ardu in Curridabat, who never let me down. Thanks to its writers and loyal advertisers over the years, the Howler has grown in stature until the present day.

In the meantime, the Tamarindo area has seen many improvements. The road to Villarreal was paved, as was the road to Flamingo, and then to Santa Cruz. A really posh bridge now crosses the Tempisque River; no need to go to Liberia to get to San José. Everyone has a phone, and all banking services are available at all three banks in Tamarindo. And, lo and behold, they are paving the road to Langosta!