44 minute read

FEATURES

Falcon CrestA Jersey City couple resurrects a 5,000-year-old sport

By Tara Ryazansky Photos by Max Ryazansky

Advertisement

Birds are common in Jersey City. Aside from flocks of pigeons, you’ll occasionally see a cardinal or even a pheasant in Liberty State Park. Yet, the sight of a bird of prey swooping in on a mouse seems more like something you would see in a nature documentary than in Lincoln Park. Unless you happen to run into Emilio and KristieAnn Ramos.

The Jersey City couple practice falconry. They bring their Harris Hawks, Bodhi and Ariya, and Red-Tailed Hawk, Billie, to hunt for small animals like squirrels in Lincoln Park and Liberty State Park. These birds aren’t their pets, despite the clear bond.

“It’s the art of training a wild bird to hunt prey,” Emilio says. “The sport of falconry is like getting to watch the Discovery channel up close.”

Emilio is a retired Jersey City police officer. KristieAnn proudly points out that he was the first Filipino police officer in the department.

“I retired two years ago from the bomb squad as an emergency-service bomb technician, one of the snipers for the SWAT team, and a scuba diver for the department,” he says.

Love at First Flight

He found the sport about ten years ago when a friend who practices falconry took him to watch his bird scare pigeons away at the Liberty State Park terminal. Emilio was instantly hooked. His friend warned him that falconry can become all consuming. “He told me if I didn’t have time on my hands, don’t do it because it becomes a lifestyle.”

KristieAnn, who is semi-retired as an activity director for an assisted living community, did not get into falconry as quickly as her husband. She would join him when he took his Red-Tails to hunt, but she wasn’t interested in pursuing the sport. Five years ago when Emilio got Bodhi, his first Harris Hawk, KristieAnn’s interest grew.

“I saw how well the bird flew with him, and how our dog, Khaleesi, worked with the bird,” she recalls. Emilio got a female Harris Hawk, Ariya to join the male, Bodhi. “When I saw him flying them together as a cast, which is where they hunt together, it was the coolest thing,” KristieAnn says. “It was even cooler to see them get one rabbit.”

Soon after, KristieAnn was injured at work. The pain from her injury made it difficult for her to sleep. Emilio urged her to use that time to study while she was up late at night. KristieAnn passed the falconry exam and got her certification a year ago. She is among less than 600 female falconers nationwide.

Conservation, not Cruelty

“As an apprentice you have to trap your first Red-Tail,” KristieAnn says. The description that follows may be unsettling to some readers, but there are permits, licensing, and regulations for the safety of animals. Falconers must obtain a falconry permit from the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife to safely trap their birds.

Trapping a falcon involves lying in wait with a pigeon in a harness or a gerbil in a netted wire cage that will lure the bird. When the hawk comes down to get its meal, it gets caught by its talon. Neither the bait animal or the hawk is harmed.

“Most falconers are interested in conservation,” Emilio says, noting that bringing the young falcons into captivity greatly improves their chances of survival. Many don’t survive their first winter. According to the New Jersey Falconry Club, 75 to 80 percent of immature raptors die each year.

Falconry has also been instrumental in supporting endangered species. “Peregrine numbers are up because falconers all over the United State raised them in captivity,” Emilio says. “Some gave their birds to Cornell University to breed them. Now in New Jersey alone there are 50-75 breeding pairs.”

The couple, along with their falconry club, put up Kestrel nest boxes and owl boxes so that endangered species have a space to nest and have babies. “We truly believe in conservation,” Emilio says.

Good Omen

Meanwhile, the Ramos’s were out for their second weekend trying to trap a Red-Tailed Hawk for KristieAnn. “I had a good feeling that day,” KristieAnn recalls. “We left for the Meadowlands at 7:11 in the morning, and I was like, ‘look at the time.’” The couple’s neighbor, Billy, had had recently died. His birthday was July 11. “Whenever anyone asked when his birthday was, he would say 7/11. It’s a lucky number.”

Within an hour they got the bird.

“We hooded the bird and wrapped its talons in masking tape,” KristieAnn says. “After that you take a stocking to wrap the body. It’s almost like you’ve got a gentle baby in your arms.” She named the bird Billie to honor her neighbor, choosing the feminine spelling because the hawk is female. Females are larger than males.

Once Billie was freed from her wrap and cleaned of mites and bugs, the training began. “It’s a wild, wild bird,” KristieAnn says. “The fi rst thing you want to do is get it up on your glove. It took about seven days to get this bird to feed off of my glove comfortably. I can put food on my glove, but I can’t make the bird eat it.”

Training and Television

Next it was time to train the bird to hunt. This involves getting her to jump back to the glove after a fl ight. “People say, ‘How do you get this bird to come back to you?’ There’s steps that you take to build that relationship.”

Falconers wear heavy leather gloves and high boots. The hawks wear hoods and an anklet attached to either a jess, which is a short leather strap or a creance, which is a longer line that attaches to the grommet of the bird’s anklet. “The creance is almost like a longer leash,” Emilio says. “When you’re training a bird, you start at one foot; the next day you might be at three feet.” Eventually Billie was fl ying 150 feet on the creance.

The next step in KristieAnn’s apprenticeship was to build a mews, or hawk house. Despite having these structures, Billie, Ariya, and Bodhi sometimes join the couple in their Jersey City home during the winter.

“My general rule is if it’s below 20 degrees we bring the birds inside so that they don’t suff er the cold,” Emilio says. “They go in the basement on their perches and basically hang out and watch TV. They watch anything that we’re watching, action movies, sports.”

The Wild Blue Yonder

When spring emerges they are outside and hunting again. For KristieAnn, there’s an element of physical therapy in taking Billie to hunt. The sport involves some running and lots of time outdoors. “It’s been a big challenge for me because of doing it and having this injury,” she says. “Some of your aches and pains go away because you’re focusing on the bird.”

“We do love training our birds and hunting our birds,” Emilio says. “It’s more about the bird than catching something. It’s about the bird training and fl ying. When you watch the birds fl y it’s very artistic and beautiful.” He says the sport dates back fi ve thousand years. He appreciates the rich history, but he also just enjoys falconry. “It’s fun. If it wasn’t fun, I wouldn’t do it.”—JCM

POINT & SHOOT

OUR NEW REALITY

Photos by Victor M. Rodriguez

A TORCH The Rambusch tradition of excellence continues for All Seasons

By Diana Schwaeble Photos courtesy of The Rambusch Family

Few icons hold as much universal signifi cance as the Statue of Liberty. Standing vigil in the Hudson River, Lady Liberty has been a beacon of hope for countless generations of Americans, or anyone searching for freedom.

Tasked with moving and repairing the torch of the Statue of Liberty is no small feat. Were it any other company but the fourth generation of Jersey City’s Rambusch Company, the job might seem too daunting. Working on historic buildings, museums, and cathedrals is all in a day’s work for the storied company, which has completed hundreds of signifi cant and lasting commissions.

The twin brothers Martin and Edwin now lead the company. While the breadth of the work has changed, their work ethic has not. First generation master painter Frode Rambusch founded the business in Manhattan in 1898, focusing on painted decoration, glazing, and murals. Four generations have refi ned and expanded the work. Though Martin and Ewin are twins, they have diff erent sensibilities, and they head diff erent divisions of the company.

“Edwin runs the lighting,” Martin said. “Custom lighting and what we call standard lighting. Custom lighting would be a one-of-a-kind chandelier or a piece of metal that has a glow. I’m involved in crafts, which is stained glass, church furnishings, artwork, and then the sale and coordination of that as well.”

Recently, I visited their Jersey City factory, which looks unremarkable on the outside, tucked on quiet Cornelison Avenue. The shop is not what you’d expect, especially when you consider the majesty of their work: temples, monuments, and memorials. Though their work often honors the dead, it is a testament to life.

Carrying a Torch

When the National Park Service and the general contractor, Phelps Construction Group, started to develop a team to work on the torch, they asked Rambusch if it wanted to be involved. “It’s really not hard to fi gure out what the answer should be other than, ‘sure, of course,’” Martin said.

Not everyone can do this kind of work, and fewer now choose it. They have 30 full-time employees. But attracting craftspeople to work on tile or a light fi xture for $30 an hour is tough when they can work as a plumber and make almost twice that, Martin said. Or work making code for $150 an hour. The biggest challenge is fi nding talented people, he said, adding that there must be a balance of art and craft.

“We are interested in having capable, artistic people,” Martin said. “We are looking to work with craftsmen more than artists, because their capacity is to craft several things. It’s not one perfect piece. And if the client says they don’t like it, they don’t run away and destroy it.”

Image by TBishPhoto

A Two-Year Plan

It took about 18 months to develop a plan for the torch project, Martin said. They were told that the plan was to move the original torch from the base to the new museum. The finish and condition shouldn’t be changed, and it needed to be illuminated. They discussed the right source of illumination, including the color and density. Edwin had previously worked with a LED system that is tunable by color, volume, and density. Using LED to light the torch became a very attractive solution. “So to have an infinite color solution made us comfortable that we could reach the unknown of what their request was,” Martin said.

Moving the torch to the new museum was a two-week process. They would board the last boat at 3 p.m. and start work at 5 p.m., working until 2 or 3 a.m. They had to be sure to have everything needed since they were working on an island. Not to mention, the issue of working at night. “It sounds romantic until your whole sleep schedule is all off,” Martin said. “They say you can sleep until 10 or 11 a.m., and you are still up at 6, and then someone is calling you at 8:30 a.m. There was a challenge of putting a whole day into your already full day.”

“And then the challenge that we wanted to move on pace and on schedule,” Martin continued. “There was nothing more important than the Statue of Liberty. There is one, there is no other. Therefore, what is the old saying? ‘Slow is fast. Smooth is fastest?’ The enormity of what you were doing, which in one minute is really exciting, and the next, holy Christmas, I have to really be careful here.”

The process included cleaning, documenting, prepping, dismantling, and moving. They spent another three weeks blending the finish, which was done within conservation standards, without impacting the original finish.

Image by TBishPhoto

“When you are on the torch—and we were lucky enough, because we were working on it— it’s a fragile thing,” Martin said. “It moves. It’s not rock solid. You’re almost on a boat. There is a little move and shake, which makes total sense.”

Lady Liberty’s Lore

Visiting the Statue of Liberty can spark vivid memories, not always reliable.

Martin related, “There was an introduction at one of the ceremonies, and the director of the tour said, ‘Well, everyone will tell you that they have been on the torch of the Statue of Liberty, which is impossible. It’s been closed since 1917. You were in the head, and you looked at the torch. But everyone tells you they were on the torch.’”

Martin said that it became clear that the fewer changes they made, the more successful the project would be. “We just put back what was there,” he said. “So we took out 15 sources of illumination, and we put back 15 sources of illumination in the exact same location.” The change was simple. It went from an incandescent source to an LED source.

Did we Mention the Vatican?

At the Rambusch factory, there is no idle chatter near the breakroom or separation between executives and staff. Everyone is united in purpose. Martin and Edwin stroll the floor on an equal footing with their craftspeople. They’re working on things bigger than themselves, big enough to mark history.

But Martin will tell you that they don’t think of the magnitude of a project, though they’ve worked on the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in D.C., the Boston Public Library, the Cathedral of St. Catherine of Siena, and the Count Basie Theatre in Red Bank, to name a few.

“We were lucky enough to work on the New York Fire Department’s memorial to 911,” Martin said. “Those spaces, those environments we are designing, shaping, crafting, are precious to that community.”

Martin is not given to touting the significance of their work. It was an hour before he mentioned that they had just completed work at the Vatican: “Last summer we created and installed a statue at the Vatican. That was very exciting. So after 122 years of doing work for the Catholic Church, we have a piece now at the Vatican.”

Martin points out recent work. Competing with the sound of metalwork is the silence of the space, with vast ceilings and religious icons everywhere.

“We’re lucky to have been involved in some wonderful projects,” Martin said. “You don’t always listen to your parents, but one of the things my dad said is, ‘I feel sorry for you boys. You are going so fast that you really can’t take a breath to appreciate some of the beautiful things you are doing.’ Which is true. So from a point of view of history, we’ve been very, very lucky.”—JCM

SACRED HEART’S

Surviving December 10, 2019

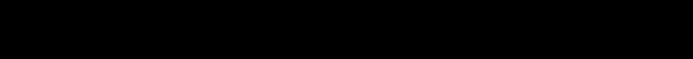

Students waiting in Sacred Heart Church on the day of the shooting

By Kate Rounds Photos courtesy of Rosemary Sekel

On Thursday, December 5, 2019, 34-year-old Jersey City livery driver Michael Rumberger picked up two passengers at the Hudson Mall in Jersey City and drove them to a moving company at West First Street in Bayonne, where he was shot in the head. His Lincoln Town Car was driven to 17th Street and John F. Kennedy Boulevard in Bayonne. On December 7, Rumberger’s body was found in the trunk.

Rosemary Sekel, advancement director at Sacred Heart School at 183 Bayview Avenue on the corner of Martin Luther King Drive in Jersey City, recalls that she probably left later than her usual 5:30 p.m. on December 5 because the next day was open house and report card day. “The teachers may have been putting the fi nishing touches on decorations Thursday evening,” she recalls. “After that,” for her, “it was Route 78 and All things Considered.”

On December 10, Jersey City Detective Joseph Seals went to Jersey City’s Bayview Cemetery to meet with a confi dential informant. According to a senior law enforcement source, it was not related to the Rumberger murder.

The cemetery, built in 1848, features classic gravestones, tombs, and worn paths, with sycamore trees standing guard. It’s bisected by Garfi eld Avenue. To the west roars the New Jersey Turnpike, with the public Skyway Golf Course across the way. To the east are views of New York City, as the graveyard slopes down toward Liberty National’s PGA greens.

According to U.S. Attorney Craig Carpenito, Seals saw a white U-Haul van parked in a spot that made him suspicious. When he investigated, the occupants who had been living in the van, opened fi re. One media outlet reported that Seals had been shot behind the ear. At about 12:38 p.m. the Jersey City Police Department received a 911 call from an individual who discovered Seals. The detective was pronounced dead at Jersey City Medical Center, leaving a wife and fi ve children.

DAY OF DELIVERANCE

At about 12:21 p.m., a white U-Haul van, emblazoned with an ad announcing its rental price of $19.95, ran a red light at Bidwell Avenue traveling south on MLK Drive. Seconds later, it parked along the curb outside Sacred Heart School. The school, established in 1913, originally served Jersey City’s growing immigrant population and today refl ects the diversity of MLK Drive with its large African-American community.

David Anderson, 47, driver of the white U-Haul, exited the van with a long rifl e and began to fi re on the JC Kosher Supermarket at 223 MLK Drive. The store, which caters to the Hasidic community, has a sandwich bar and shelves packed with popular kosher items. Cholent and kugel are freshly-made on Thursdays.

“There’s no question it was an attack on the Jewish community,” Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop said at the time, noting that the kosher market abuts a synagogue and yeshiva.

“Before the shooting began, we received two blessings,” Sekel recalls. She is a short, loquacious woman, devoted to the school. “The day was unusually mild for December, and our eighth-grade teacher rang the bell to end recess for the second lunch about two minutes early. Recess is held in the parking lot next to our cafeteria/ gym building. This is about 200 to 300 feet from the school. Most of the lunch classes were back in the school except for the seventh grade. They were walking into the building. I was in the computer room, which is just a few feet from the main entrance, the offi ce, the teacher’s room, and nurse’s offi ce.” She was with Sister Frances Salemi, Sacred Heart’s Principal.

As Anderson crossed the street in the rain, he left the driver’s side door open. Francine Graham, 50, exited the passenger side and followed Anderson into the store. People on the street scattered, running in the opposite direction and ducking behind parked cars. The assailants, both wearing tactical gear, fatally shot co-owner Leah Mindel Ferencz, employee Douglas Miguel Rodriguez, and customer Moshe Deutsch, a rabbinical student.

The assailants were implicated in the Rumberger murder of December 5.

“We are an inner-city school and to hear what is probably a gunshot is not unusual,” Sekel says. “Within seconds, though, the second volley of shots rang out, and they were defi nitely more war than inner-city gunshots; everyone started reacting.”

At approximately 12:22 p.m. two Jersey City Police Offi cers who were one block south on patrol heard the shots and ran to the scene. Two minutes later, marked and unmarked police vehicles arrived and established a perimeter. At about 12:43 p.m., JCPD offi cers drove up with a BearCat armored personnel carrier.

Sister Frances often arrives at Sacred Heart at 5:30 a.m. She lives in Newark with the Sisters of Charity and drives to the school every day on Route 1 and 9. On December 10, she arrived at 6. She recalls that it was cold at that hour. She entered through the back door, made coff ee, and sat down to some paperwork. A few students arrived as early as 7 a.m.

Sister, a sturdy, casually-dressed woman of a certain age, exudes confi dence, kindness, and gentle authority. Bullet holes were still evident in her offi ce to the right of the front entrance at a midJanuary meeting. She has an “open-door policy.”

The seventh-grade class, now in the front hall, instinctively dropped to the ground. Their teacher motioned to the girl holding the door to quickly close it. The class stood and ran upstairs.

Sister Frances announced over the microphone, “Lockdown, shelter in place.” They sheltered in place for three to four hours on classroom fl oors. Sister answered the phone in the nurse’s offi ce which rang and rang. School Secretary Evelyn Roe was under her desk, sending a blast message to parents that the school was in lockdown, and the children were safe. Later, kids made a Christmas plaque to cover a bullet hole in Roe’s offi ce.

After about 45 minutes, the police, who had been all around the school, were buzzed in. “Since we were directly across from the schul and the grocery store, Sacred Heart was the only spot from which they could fi re back into the store where the shooters had killed three people,” Sekel says. “They shot back from the classrooms on the side of the building across from the store.”

At approximately 1:49 p.m. bodycam footage released by the Offi ce of the Attorney General shows an offi cer with a handgun in an upper fl oor classroom of Sacred Heart School returning fi re coming from the kosher market.

At about 1:50 the offi cer reports, “I think he’s down … I got a gun on the ground. Nope he is still moving behind the, behind the wood.” He continues to return fi re.

Flowers were left after the shootout.

Bullet casings fall on the school’s windowsill atop a children’s book. Two magazine clips rest on a box on the sill to the officer’s left.

A minute later, the officer begins to move through the desks, out into the hall past a series of gray lockers and red classroom doors into another classroom, weaving through desks to a far-left window. “He is still moving,” he reports before continuing to return fire out the window.

Paper candles and angels blowing horns are taped to the windows.

“We didn’t know exactly what the nature of the attack was,” Sekel relates. “There were periods of incredible automatic gunfire, booms that sounded like cannons and then silence, sometimes for 20 minutes, a half hour, and then more gunfire. Lying on classroom floors, huddled with absolutely silent children, I think we all experienced some of its frightening cacophony.”

Sheltering in place doesn’t work so well when bullets are coming into the place where you’re sheltering, she noted. “Our seventh-grade teacher deviated a bit from emergency procedures. When he and his class reached the second floor, he carefully looked out the MLK Drive windows and realized that that side of the building was in the crosshairs of the perpetrator, directly in the line of fire. He let his class continue to the third floor.”

After alerting Sister Frances, three teachers made their way to classrooms on the second floor on the MLK side of the building, knocked, and got the children to crawl across the hall into safer classrooms.

The active shooter protocol dictates that when you have a lockdown, under no circumstances should you unlock and open a classroom door, no matter who’s there or what they say. “Thank God the teachers in the classrooms on the safer side relied on their instincts, made a difficult judgment, unlocked their doors, and let the children in,” Sekel says.

Parent Melissa Germain

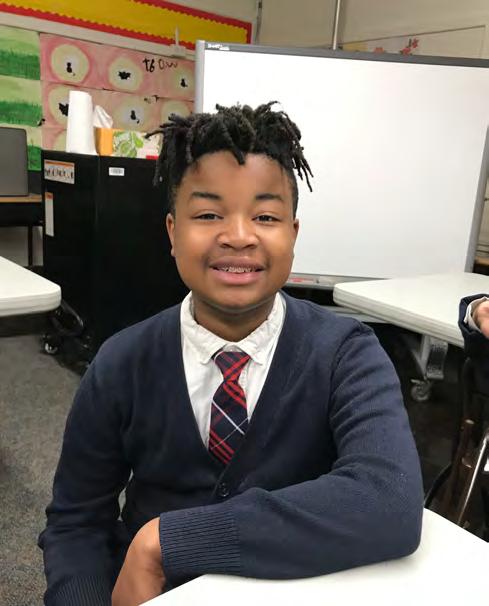

Student Blake Davenport

Principal Sister Frances Salemi and Kenya Curry

Ajah Archibald and Sister Frances Salemi

At approximately 3:25 p.m., the BearCat armored personnel carrier rammed through the storefront and engaged with the two suspects.

The van, outfitted with ballistic panels, contained five firearms: an AR-15, a 12-gauge shotgun, a 9 mm Ruger semi-automatic, a 9 mm Glock 17, and a 22 Ruger Mark IV with a homemade silencer and homemade device for catching bullet casings.

The van was later found to contain pipe bombs that could kill or injure people up to 500 yards away, as well as enough material to make a second bomb.

At approximately 3:47 p.m., the shootout ended. Officers found five bodies inside including those of Anderson and Graham.

“At about 3:30 or 4 we were rushed to the basement, where we stayed for about 45 minutes,” Sekel relates. “We had 200 children. The basement is not only safer but it is where the bathrooms are. Only the boys’ room could be used because the girls’ room had a window facing the street. Children were allowed to go to the bathroom one at a time with an adult. The Kindergarten class put the tables on their sides to make a fort-like barrier.

“Police instructed us to make sure all the children were accounted for, line them up two by two, count off 20 at a time, and escort them up the back cellar stairs across to the priory, 30 feet away. It was lined with police.” Teacher Siony Delos Reyes

The priory is connected to Sacred Heart Church, designed by architect Ralph Adams Cram, who designed New York City’s Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Sacred Heart is a massive Gothic affair standing on the northeast corner of MLK Drive and Bidwell Avenue.

Class by class, the children used the church’s one bathroom. “It was a blessing that the day was warm,” Sekel recalls. “The church is big and takes a long time to warm up. Many of the children did not have their coats.”

Together, they recited The Lord’s Prayer. Blake Davenport, a seventh grader on the upper floor, has siblings in the school. “I was thinking about my brother and sister on the lower level,” he says.

One girl reveals, “I was the first to cry.”

Melissa Germain, a parent, reports that after the shooting, her son, Joshua, a second grader, was disturbed by noises. “Our neighbors were doing home renovations,” she says. “He heard tools they were using on their house and automatically thought it was a shooting.”

A woman who has three children in the school had already lost a son to gun violence. She wrote to Sister Frances, “You told me you would always keep my children safe. You were true to your word.”

Siony Delos Reyes teaches first grade. She has three children of her own. Like any mother, she says, she would lay down her life for them in an instant, but she wondered if she would do the same for her school children. If she did, she would never see her three girls again.

“I felt so blessed that day,” she says. “I think on that day I would have given my life for the children.”—JCM

Hudson Reporter staff writer Marilyn Baer contributed research for this story.

Olena Yakobchuk | Shutterstock.com

Zooming Along How one fitness instructor adapted to the new normal

By Tara Ryazansky Photos courtesy of Laura Miller

Fitness instructor Laura Miller isn’t afraid of change. “I had the corporate job, and I really changed it up to be selfemployed,” she says. “But I wasn’t forced to adapt. I chose to.”

Even when the coronavirus shutdown required nonessential businesses to close, Laura met the challenge and found a way to adapt her business model to work during the quarantine.

Miller created HipFit dance fitness in 2014. She felt she had become less active while stuck behind a desk at her ad agency job. She had danced throughout her childhood and continued with classes until she graduated from high school. “I was taking Zumba classes here and there, but it just wasn’t hitting the mark,” Laura says. She wasn’t that into the moves or the music. “I always loved hip hop.”

This inspired her to create HipFit. “It’s combining hip hop and fitness,” she says. “It’s about an hour long, and there’s no prior experience required. I just suggest you enjoy dancing as cardio. I’m combining dancing with a lot of exercise movements, but it’s not really 80s and workouty. I want people to feel like they’re learning some moves that they can take to the club.”

Entrepreneur Extraordinaire

Laura built two businesses simultaneously when she left her ad career. Along with HipFit, she created a hand-painted signage business called Letter by Laura. Her sign business took off and became her primary source of income while she taught HipFit classes at Grassroots Community Space at 54 Coles Street.

“The whole program really started very small,” Laura says of HipFit. In the early days, there were times that only a few people showed up. The class grew and would typically meet up four times a week. “It has since really transformed into such a wonderful community of people who have become friends and acquaintances,” she says “It’s supportive and nonjudgmental. Not to mention they’re getting a great workout and having some fun. I think people really look forward to this class. They’re not dreading it like you might dread another type of workout.”

When Coronavirus came along, the workout classes stopped. Letter by Laura took a hit, too, because area restaurants made up the majority of Miller’s clientele. No one needed a beautifully written specials board amid a pandemic. Miller turned her focus to HipFit.

HipFit at Home

“I had those financial burden concerns, but just as important was not letting the HipFit community down and not losing this

community,” Laura says. She decided to instruct her fitness classes online. “I threw myself into trying to stream some classes. I had no idea what I was doing.”

Soon, Miller found that the best solution was holding her class meetings via the Zoom video conferencing app. This way her clients could Venmo her payment and then access info to join the class via laptop or mobile device.

“Now I have it figured out,” she says. “The beauty of it is that so many people turned out online to take this class.” She made her Jersey City home into her new gym. “I’ve transformed my little spare room into a studio.”

A Timeless Trend

Plenty of Jersey City residents are carving out space for at-home fitness. Despite gym closures, fitness remains a priority. “A lot of feedback that I’ve gotten is that people have been feeling very anxious and HipFit has been a relief from that,” Laura says. “Things like that really touch my heart.”

Laura thinks that even when we become less isolated, home fitness will remain popular. “These options will be out there more and more,” she predicts. “It’s interesting to see HipFit translate so well. You know, you’re in your apartment alone dancing, but

Remember the days before masks and social distancing?

people are into it. They’ll do some hip-hop dance cardio at 8 in the morning.”

Before the pandemic, Laura regretfully put HipFit on the back burner in favor of her lettering business. Now HipFit has her full attention.

“I am really focused on HipFit, and it’s really rewarding, Laura says. It’s reaffirmed that I need to spend more time on this. When things get back to normal, and we’re back to the studio, we’re going to keep this going. I’m really proud of the class and the community it’s garnered.”—JCM

It’s in the CARDS

A Jersey City artist makes cards, kits, and critters

By Tara Ryazansky Photos courtesy of Erin Fox

Like most kids, Erin Fox made construction paper birthday cards when she was little. “We’re very much a snail mail family,” she says. “My mom even does handmade cards.”

Fox studied graphic design and did illustration, but her artwork never made it onto greeting cards until three years ago.

She was working part-time at Kanibal & Co. on Montgomery Street in Jersey City. Shop owner, Kristen Scalia approached Fox about making a custom holiday card. “Since Erin is one of our staff members here as well as a local illustrator it felt like a good partnership to create a custom line for the store,” says Scalia, who loves working with talented Jersey City locals. “This way the money goes back to the artist, which goes back into Jersey City as a whole. It’s always been an important mission of the store to also support the community which supports us.”

“I never put two and two together to make a line of greeting cards until Kanibal,” Fox says. That fi rst card, which featured a steaming mug that

reads Seasons Greetings from Jersey City held by mittened hands, is still available at Kanibal & Co. online.

A Card Company of Her Own

The success of that fi rst endeavor inspired Fox to create more. Now, under the company name Moxie Fox she sells cards that fi t many occasions.

“I have sympathy, thinking of you, engagements and weddings, thank yous …” The list goes on. “I love that in general, handmade stationery has been taking off . It’s an actual little team or person making this little piece of stationery for you, which is diff erent than your glittery Hallmark card,” Fox says.

The product is diff erent too. One of her wedding cards features bride and groom skulls and says “Together Forever.” It’s a unique take on “‘til death us do part” that you probably wouldn’t fi nd mass- produced. Fox says. “They can be funnier. They can have swear words and be a little off the beaten path.”

Moxie Fox makes more than greeting cards. She’s created custom wedding stationery. “I’ve done everything from quirky couple portraits to elegant fl orals,” Fox says. “It’s always fun to learn a couple’s style and personality.

I especially love helping with the little things like matching labels for favors, or cute bar signs. It’s almost like creating a brand package for a couple, and making sure everything cohesively matches their wedding vision. I love it.”

Very Crafty

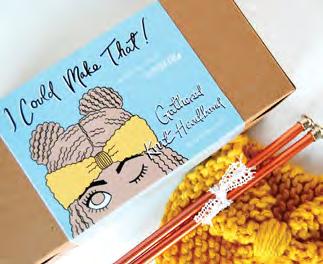

Fox also created I Could Make That! DIY craft kits for adults. These easyto-use kits contain the necessary supplies and information to help beginners make things, like a knit cowl scarf, ear warmer headband, felt succulent garden, or chic tassel necklace. They could be the perfect item for folks who are feeling crafty during the quarantine.

“I wasn’t seeing anything out there that was easy and giftable,” Fox says. “It’s good for offi ce gifts and white elephant gifts too.”

Fox has used her illustration skills to collaborate with Kanibal & Co on the Animals of Jersey City collection. “Being a local business, we often have customers with fur babies that come into the store to shop,” Scalia says. This inspired Scalia to urge Jersey City pet owners to submit photos of their animal friends on Instagram tagging @shopkanibal to enter the Animals of Kanibal contest. Check out #AOK19 to see the 2019 entries. Ten to 15 randomly selected critters have their portrait done by Fox. Last year’s winners included rescue mutts, purebreds, kittens and a trio of chickens.

“I can’t pick a true favorite because people will be mad, but I love pit bulls with smiley faces,” Fox says.

The pet portraits adorn merchandise like tote bags and coff ee mugs. A portion of the proceeds from these items supports animal charities such as See Spot Rescued and JerseyCats.

After the contest, pet owners reached out to see if they could commission Fox for custom portraits. “I’ve always been doing that for friends ‘cause I love animals, and they’re fun to draw,” Fox says. “The local vet started buying them, and there are rescues in town that I sort of work with too. It just kind of trickled out of the shop.”

This led Fox to launch a new website with a Build Your Own Custom Pet Portrait section. It also inspired her to teach a Pop Art Pet Portrait class at Kanibal & Co.

Small Business Boost

“It’s a great way to meet people, and Kanibal supplies the wine,” Fox says of the events, which are on hiatus for now. Participants walk away with a cool piece of art they’ve made themselves. The artists who teach the classes earn 100 percent of the profi ts because Scalia doesn’t take a cut.

Fox was recently awarded a grant from the Jersey City Project through its newly launched Small Business Grant Fund. “It was amazing to have been one of the small businesses selected to receive a grant from JCP,” Fox says. “It was just the boost I needed to upgrade my equipment and therefore expand my services. I am so grateful for their help and support.”

“My personal business really took off after moving here,” says Fox who came to JC by way of Pittsburgh. “At Kanibal, customers want the stuff that’s local. They want the stuff that’s handmade. Plus there’s a community of makers. You can reach out to anybody, and everyone is so supportive.”—JCM

e-mail: hello@themoxiefox.space website: www.TheMoxieFox.space etsy: TheMoxieFox.Etsy.com

Photos courtesy of the Leal-Morehouse Family

John Leal

Jersey City’s unsung hero

By Pat Bonner

In the years before the turn of the twentieth century, Jersey City was booming. It was the terminus for several railroads, and due to immigration, population was increasing rapidly. The city had been taking water from the Passaic River near Belleville. However, as Paterson developed, sewerage was being pumped into the river near this site, and Jersey City had to make other plans. It stopped using water from the Passaic in 1895 and made a shortterm contract with East Jersey Water Company to use water from the Little Falls waterworks. Later, there was litigation over this, but it was merely a stopgap. The city needed a safe water supply and solicited bids for a permanent solution.

Big Bucks, Bad Blood

The bidding process was complex and litigious. After eight requests for bids and assorted lawsuits, the city awarded the contract to a notorious local businessman, Patrick Flynn. Flynn may have been behind the East Jersey Water Company, but he set up a new company, Jersey City Water Supply Co. to build the waterworks. In the contract, he agreed to build

a dam, a reservoir at Boonton, a pipeline, and to supply the city with 50 million gallons of “pure and wholesome” water per day. This was a term in the contract. The city had the right to purchase the system on completion for $7,595,000, about $235 million in today’s dollars. The contract was signed on February 28, 1899. Though it had agreed to the contract, the city did not want to pay, dragging out the issue in court until the last appeal was dismissed 12 years later at the end of 1911.

The Right Resume

Flynn started the work but became insolvent. He conveyed the contract to a new company in 1902 headed by an engineering professor from Cornell University. That same year, John Leal started working for the company as the chief sanitary adviser.

Leal was perfect for the job. A graduate of Princeton University, he went on to medical school and for many years practiced medicine in Paterson. Later, he took advanced courses in bacteriology and chemistry at Princeton. His father died from dysentery contracted from unsanitary water in the Civil War, which gave Leal a lifetime interest in safe water. He had been a crusading member of

the Paterson Board of Health and was able to shut down numerous unsafe wells in that city.

Leal took center stage after the city refused to pay for the project. It sued, arguing the water company did not comply with the contract. Leal was the guiding force and primary expert witness at the two trials between the parties.

See You in Court

The first trial was largely a draw. The judge ruled that the city had to pay for the construction of the dam, the Boonton Reservoir, and the 23-mile pipeline. However, he did accept the city’s argument that the water was not completely “pure and wholesome” because several days a year, usually after a large storm, the bacteria count was too high.

The cost of constructing sewers to capture the waste would have been very high. Rather than deducting an amount for the construction of sewers from the purchase price, the judge gave Leal and his company 90 days to come up with “other plans or devices” for making the water pure and wholesome year-round. This wording about other plans or devices was key because it opened the door for Leal to put his theory about chlorine into practice.

Today, we put chlorine in our pools, but at the time of the trial, February 1909, it was seen as a poison. A few visionary water engineers, including Leal, had discussed using it as a disinfectant, but it had never been used in the water supply for a medium-sized city.

The C Word

At the second trial, the city was prepared to argue about the cost of constructing additional sewers and how large a credit it should receive on the contract price, when it was surprised to hear Leal proposing using chlorine to treat the water. The experts for the two sides were arguing about whether chlorine was safe when Leal testified that he’d been secretly adding it to Jersey City’s water supply for the

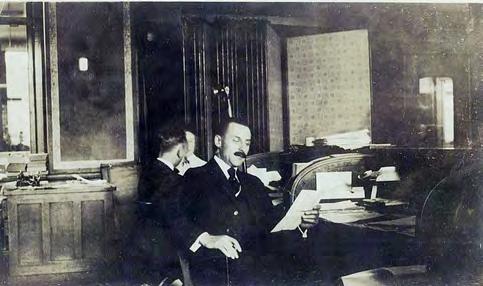

(l-r) Author Michael J. McGuire, grandsons Scott and Hank Morehouse previous four months. Both sides had been testing the water daily so no one could argue that the water was not sufficiently “pure and wholesome.” In fact, the trial had been going on for some time, and everyone in the courtroom had been drinking the chlorinated water without knowing it. Leal and his company prevailed in the lawsuit, and Jersey City became the first city to chlorinate its water.

Safe Water Saves Lives

Among the diseases caused by contaminated water is typhoid. With the U. S. population increasing and rapid industrialization, typhoid was rampant in the country in the first decade of the twentieth century. Following Jersey City’s successful experimentation with chlorine, its use exploded across the country and the world. A number of cities began using chlorine in the years 1910-1913. All lowered the typhoid death rate. Omaha lowered the rate by 59 percent; Kansas City, 53 percent; and Erie, Pa., 65 percent. By 1941, the Census Bureau estimated that 85 percent of the U.S. water supply was chlorinated. Before 1908, when chlorination was introduced, there were about 30 deaths per 100,000 due to typhoid. The number of lives saved is in the hundreds of thousands if not higher.

Anonymous Source

Leal never received the accolades he deserved. Recently a selfdescribed “drinking-water guy” named Michael McGuire has led the effort to recognize Leal. He has written an excellent book, The Chlorine Revolution. Leal’s body had been in a grave with no monument or headstone. McGuire and others erected a marker reading “John L. Leal–Hero of Public Health.” In fact, many in the field call John Leal our nation’s “Father of Public Health.” No schools are named for him, and he did not win a Nobel Prize. But his story and the fight for chlorination make a pretty good Jersey City yarn.—JCM

Feeding the Needy

Luck Sarabhayavanija

How one business is coping with Corona

Nicholas Wilkins

By Tara Ryazansky Photos by Max Ryazansky

Intimes of change businesses have to adapt, and Ani Ramen has done that in a big way.

As COVID-19 pushed Jersey into social isolation, the first step was getting folks home earlier instead of crowded into bars at night. Owner Luck Sarabhayavanija closed Ani Ramen about a week before it was mandatory. “We couldn’t live with ourselves if we were part of that spread,” Luck says.

Feeding the Soul

But even with Ani Ramen temporarily closed, Luck kept the business going, selling gift cards online. He doubled every gift card so customers could spend $25 to get a $50 card. They can be used now that Ani Ramen has reopened its Hudson Street location for delivery and pickup orders.

On March 19, Luck handed out prepackaged ramen kits.

“We wound up giving out 15,000,” Luck says.

A woman walking by was an essential worker at a nursing home that was in need. Luck said he would give her 100 bowls for her clients. “She whipped the minivan around, and we loaded the bowls up.”

Closed Doors, Open Hearts

Luck’s childhood friend, high-end hairstylist Mark Bustos, “goes to New York and gives haircuts to the homeless,” Luck says. He wanted to collaborate with Bustos under the

#beawesometosomebody movement Bustos created.

Ani Ramen became the temporary home of two nonprofit popup takeout concepts, Rock City Pizza Co. and Bang Bang Chicken. Instead of offering ramen, Ani Ramen’s Newark Avenue location sold Detroit style pizza and Thai spiced rotisserie chicken via takeout and delivery.

The plan was to sell each item at a lower-than-normal price in hopes that customers would add a little extra to their tabs to donate a meal to essential workers and those in need. Pizzas were $11-$13. Adding an extra $6 buys a donated pizza. Chicken was $15-$19, and $8 provided a free meal. Fifty percent of the donated items were delivered to area hospitals and first responders. The other 50 percent was distributed to locals in need. It has fed more than 30,000 people.

Ani Ramen used #beawesomefeedsomebody as its Instagram hashtag. It’s documenting the popups at @beawesomefeeds and @ aniramen.

Luck launched a Kickstarter where folks preorder meals and donate. He hired back about 20 percent of his staff. Luck and his partners are not taking a salary.

“No one prepares you for a pandemic,” he says. “I think it was Teddy Roosevelt who said, ‘the worst thing you can do is nothing.’”

Ani Ramen opened its Newark Avenue location in late August as an Ani Ramen Express.

Ani Ramen’s motto is “slurp, sip, repeat,” but it seems like during the pandemic, it’s more like “Give back, repeat.”—JCM

Kevin Cox