19 minute read

TEACHING AND RETRIEvAL OF NEW vOCAbULARY

TEACHING SEX EDUCATION IN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOLS

Sex education can be a tricky topic to teach and can be fraught with awkwardness, embarrassment and safeguarding implications. In this article, Ste e Sadiq explores how to approach sex education within the Catholic sector.

Advertisement

By Steffie Sadiq

Oh Year 6 - a year of SATs, production-preparation, residential visits and the all time favourite topic - sex education. Gone are the days where you could just stick a video on the tv and hope it explains everything for them!

With the rise of social media and accessibility to the latest technology, children are a lot more familiar with topics that would once have made us cringe - including sex. With the world constantly changing, how we teach sex education is even more important now, if we are to aid our children’s development.

The DfE released a compulsory Relationships Education for primary schools (Relation-ships and Sexual Education for secondary) in 2020 which resulted in the release of a Catholic RSE, aimed predominately at teaching sexual education in accordance to the teaching of the Catholic Church.

Although having a separate RSE policy ensures religious teachings are incorporated, it can be difficult to navigate teaching sexual education in a Catholic school, especially as children are aware of and inquisitive about the different types of relationships (i.e. same-sex relationships) while the majority of pupils rarely or no longer practise the faith.

Before “the sex talk”…

Some procedures have proved useful in making sure all parties (children, parents and school) are comfortable and satisfied with sex education in a Catholic context. As with any other subject, being clear on what should be taught and what the children should learn and remember is an important foundation. This means reading government policy as well as your school’s policy in deciding what to teach within your sex education lessons.

Once this is sorted, sending out a letter to the parents, which is recommended by the DfE, gives parents a very clear outline of the topics that would be covered, when they would be covered and provides them with an opportunity to ask questions and/or withdraw their child from the sessions should they choose to.

Surprisingly, I found that most parents actually wanted their children engaged in the les-sons - they just didn’t want to be the ones to deliver it themselves! Once the go-ahead is given and parents are well-informed, it’s time to prepare for the trickiest audience yet - the children.

Though sex can be an awkward conversation to have, even among adults, it’s important that children are given the opportunity to ask real questions, in a safe space, without fear judgement or having their questions dismissed. As teachers, we have a duty to ensure we are preparing our children to grow into healthy teenagers who will make well-informed choices in their lives.

Below is some guidance that I find useful in preparing the children to have a mature, yet age-appropriate, conversation about sex (this is even before we get to their questions!)

1.Set standards.

I love opening up the session by saying, “Okay, so today we will be having our RSE ses-sion which covers everything from periods to sexual intercourse.” They WILL laugh (you probably might do too!) and some might even cringe at the thought. However, when it starts getting too silly or they lose focus, I give them the option to leave the room if they feel they won’t be mature enough during the sessions. Suddenly, no-one wants to leave the room and they’ve stopped laughing (or at least calmed themselves down a bit!). This will probably need to be reiterated every session but giving them the choice to stay and be sensible or leave without any repercussions gives them a level of responsibility that will also help them in secondary school.

2. Assess their existing knowledge

Unfortunately, some children know far too much about sex by the time they’re in Year 6 whereas some children believe they came from their mothers’ belly buttons. Asking them what they already know about sex on a whiteboard that they have to keep to themselves while you walk around and see gives a good starting point on who knows

far too much, has no clue and the in-betweeners. That way, any misconceptions about sex (of which there are many) can be corrected in the safe environment of the classroom.

3. Prepare an anonymity box

Before watching the first video, explain to the children that they will have the opportunity to ask questions about anything they’ve watched, or if something comes to mind. Reinforcing that they should make sure their question is sensible, but that there are no stupid questions creates an atmosphere of trust within the class. You may not necessarily get a question in the first session but they will ask them once they feel comfortable enough. This has to come naturally and many children have to feel they’re asking this anonymously, so remind them not to write their names on their blank sheets of paper.

4. Discuss the videos

If you’re following a particular scheme, such as Ten:Ten, they provide child-friendly video and discussion questions. Use those resources.

But what about THEIR questions?

It’s important to note that their anonymous questions could address a variety of topics: be-ing attracted to the same sex, methods of contraception, even asking if it’s normal to find the thought of sex repulsive.

Before answering their questions, it’s always a good idea to preview the questions first so you know how to best answer it - now this is where the depth of the answers to the ques-tions really matters.

For example, one child asked whether you could only have sex when you get married as the video highlighted within the context of Catholic Christianity. In order to not disregard their question or society, this question was answered in this way: ‘

As we are a Catholic school, it is the Catholic belief that you are to wait until marriage to have sex. However, in today’s society, not everyone is a Catholic or religious so two people may choose to have sex without getting married but it is important to know that sex is a decision that’s made between two adults that are old enough, love and care for each other and are emotionally and mentally mature.” This could open up another conversation of what it means to be emotionally and mentally mature just as it might not. Of course this isn’t a perfect answer because it doesn’t address situations, such as one night stands - but that would be too deep. 11 year olds do not need to know about one-night stands but they do need to be aware that sex does not always happen in the context of marriage, particularly as their parents may not be married themselves.

Some topics are more sensitive, particularly topics involving the LGBTQIA+ community - if you are not sure, it’s always best to discuss the question asked with a member of SLT. The child’s name doesn’t need to be mentioned (providing there’s no safeguarding issue) and it ensures the response given will not cause any backlash or issues with the parents as ultimately, we are teaching the children about sex, not giving our personal opinions, so it is important that we protect ourselves during these sessions also.

Gone are the days where teachers could depend on a video to do the ‘sex’ talk and never have to worry about mentioning it again.

If we truly care about the education, well-being and rounded development of our children, then we have a duty to ensure we do not just focus on academic subjects, but that we also provide informative and useful sex education, for life.

• DFE RSE: https://assets.publishing. service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/1090195/Relationships_Education_ RSE_and_Health_Education.pdf

• Catholic RSE: https:// catholiceducation.org.uk/schools/ relationship-sex-education

TEACHING THE ALLEGORY OF TEACHING THE ALLEGORY OF PLATO’S CAVE TO YEAR 7 PLATO’S CAVE TO YEAR 7

Teaching the Allegory of Plato’s Cave in Religious Education can be a daunting task. In this piece, Nikki McGee breaks down how she teaches it to Year 7 and why she teaches it in this way…

By Nikki McGee

What went wrong previously in my teaching?

Our Year 7 curriculum begins with a unit that asks, “what is the love of wisdom?” which draws on Ancient Greek philosophy. The key story for this unit is the Allegory of Plato’s Cave. For many students, this is an exciting start to their KS3 RE because they enjoy the process of questioning what they once took to be certain. It is also a unit that acts as a spoiler for much of their future learning in RE. However, after reviewing the students’ work, I realised that far too many were just learning the narrative of the story and not engaging with the philosophy, there is little point in having a disciplinary curriculum if you don’t engage with the disciplines. I knew that I had to do better.

What do I want my students to know or be able to do?

I want my students to know the “gist” of the story of Plato’s Cave, they do not need the detail that an A Level student needs and whilst I want them to know that the story is an allegory, they do not have to know the meaning of every object or event. At a most basic level, I want them to connect the story to the life of Socrates and to have thought about why seeking the truth is important but can be seen as dangerous. I also want the students to consider that the word “reality” is perhaps a more complex word than they had previously thought and whether there is more to the world than their senses reveal.

What do my students already know?

At the start of the unit, the students learn that philosophy is a search for wisdom. I spend a lot of time preparing the students to read the story of the cave, laying the ground for them to see the philosophical themes rather than adding them in after they read the story.

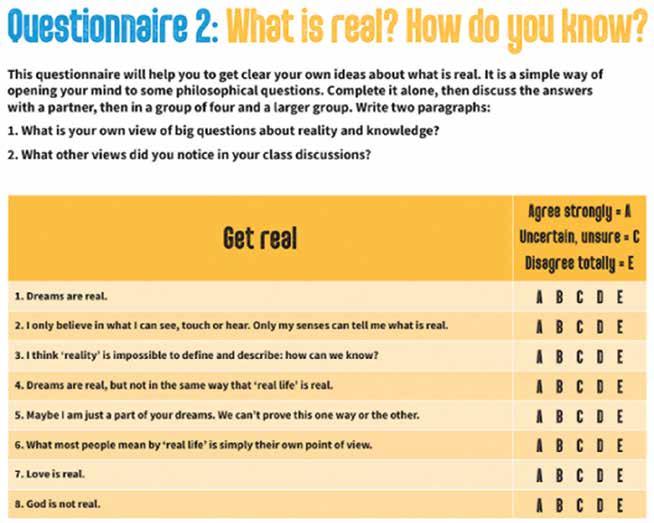

Rather than leaping straight into the world of the Ancient Greeks, we use a questionnaire from the RE Today Challenging Knowledge series called “What is real? How do you know?”. I have put this at the start of the unit to make the students think philosophically from the beginning. The questionnaire asks students to rate how far they agree with 22 different statements, many of which encourage the students to engage with the themes of reality and knowledge that underpin the allegory of Plato’s Cave. A sample of questions is below:

• I only believe in what I can see, touch or hear. Only my senses can tell me what is real. The human mind is real. We can’t see it, and we can’t touch it, but it’s there, somehow. It is in the brain but not the same as the brain.

• The material world is one kind of reality. The worlds of soul, thoughts, spirituality and emotions are real too, but in a different way.

• The word real has many meanings.

• Ideas are real, but not in the same way that atoms are real.

I use the painting, “The School of Athens” to introduce the philosophers we will study in this unit, and I then zone in on Heraclitus whom the students will merely encounter rather than study in detail. I introduce Heraclitus as a philosopher known for his melancholy and say that we are going to find out why he was so sad using the quote “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man”.

We discuss that he is melancholy because as a philosopher he is seeking wisdom about a world that is constantly changing or in a state of flux. I use choral repetition to encourage the students to use the word flux. I compare Heraclitus to my husband (the melancholy Mr McGee!) who is trying to work out how to make me happy, but I keep changing my mind and so the task feels frustrating. The students have also studied the life of Socrates, they have practised using the Socratic Method and using the painting “The Death of Socrates” we look at the trial of Socrates and how this event haunts Plato. This will help them to suggest that the allegory of the cave could represent the life and death of Socrates.

Finally, I make the students draw horses and circles. I ask them to imagine a perfect circle and draw it and a perfect horse and then draw it. It is important that they think before they draw so that a comparison can be made between ideas and physical objects. This is also an opportunity for some fun and relationship building with my new students as I put their drawings under a visualiser and ask if they really think that a horse looks like that.

We then talk about how ideas can be perfect but as soon as they become physical, they lose that perfection. If I am teaching by a window, we talk about the natural world constantly changing or being in a state of flux and therefore knowing the true nature of a tree, plant, animal or person is a challenge. We also look at visual illusions and ask if they demonstrate that we cannot trust our senses. At this point I will teach them the word empirical knowledge, again using choral repetition and questioning.

Teaching the Allegory of the Cave

I start the next lesson by asking the students to explain to me why they looked at visual illusions and drew horses and circles in their books. I deliberately left a gap in order to check their understanding before I move on to the allegory. I now teach them the words “allegory” and “thought experiment” using choral response.

It is important that they see the story as a thought experiment because this prevents endless irrelevant questions such as “How do the prisoners go to the toilet?”. It is also important that they know the story is an allegory, some students think that this is a historical account. This work is challenging and so it is important to think carefully about distractions and misconceptions and prevent them from happening, especially when you only have one hour a week. We now turn to the allegory; I will read it to them and then the students will read it again out loud. I will support this by drawing a diagram of the cave under my visualiser and looking at various images of the cave. I sometimes I get the students to very briefly act out the story as I narrate it, to help them understand who the characters are and how the shadows are created.

Some students manage to miss the shadows altogether and think that the prisoners are looking at real objects, which means that they will never understand the philosophy of the story. Once again, I am anticipating misconceptions so that I don’t have to spend time dealing with them. I will also use a carefully chosen video version, I am deliberately exposing them to lots of different versions of the story to help them remember the “gist” of the story. They will also read the story again for their homework and answer questions using a google quiz.

We then spend a lesson unpacking the allegory, very quickly somebody will say that the escaped philosopher must be Socrates and we then talk about which members of Athenian society could be the prisoners or puppeteers. We focus on the fact that the prisoners boast about their knowledge when they are looking at shadows of puppets and not even shadows of real objects. What they think is real is far removed from reality, this will help them link with our previous work on horses, circles and visual illusions and the idea that we can’t trust our senses. We also now talk about seeking knowledge in a world that is constantly changing, linking back to Heraclitus, this gets the students ready to look at Plato’s Theory of Forms in a future lesson.

I now ask the students to interpret the allegory in a modern context. We discuss who are the escaped philosophers of today. Who are the figures who get attacked for asking society face uncomfortable truths? I get suggestions that range from Greta Thunberg to David Attenborough to religious leaders. We also discuss who are the puppeteers of today, answers include social media influencers, journalists and politicians. Finally, we talk about the caves of ignorance that we live in today and this usually prompts a great discussion about social media that can be picked up in their RSE lessons. These discussions will feed into a piece of extended writing.

What’s next?

We now return to our questionnaires on reality and some students now want to change their answers, they can do this in a different colour so they can see how their ideas change over time. At the end of the unit, they will reflect on their reaction to the allegory of the cave and how it is shaping their own worldview. We will also pick key questions and ask what answers Plato might have given.

Having established that Plato thinks that we need to look beyond the physical world for knowledge, the students are ready to look at Plato’s Theory of Forms. The students’ understanding of empirical knowledge will be useful throughout our curriculum but especially when studying Aristotle and later Aquinas and Paley’s arguments for the existence of God. Discussions about change being an imperfection will also help our students consider the nature of God and finally whenever we encounter religious leaders who risk their lives to challenge society, the students will be reminded of Socrates.

References: Questionnaire Taken from Challenging knowledge in RE: Vol 2: World Views by Stephen Pett (2021)

LEADERSHIP

56. Taking Leadership To The Next Level

How to encourage and nurture diversity in school leadership

Taking Leadership To The nexT LeveL

How do we create, sustain and encourage diversity in school leadership? Tracey Leese sets out strategies that will help to nurture and broaden the range of our school leaders of tomorrow…

By Tracey Leese

At the start of every academic year, I can’t help but reflect on the beginning of my own teaching career. Sixteen years ago, there is no doubt that the cultural landscape in the profession was different. In my induction period at least, the notions of wellbeing and mentoring were a long way behind the experiences of the Early Career Teachers I work with today.

Also different was the way in which I perceived leadership. Rather than the manageable and accessible opportunity to influence students’ life chances I now know it to be, leadership seemed elitist, distant and essentially something of which I wasn’t worthy or capable. The opportunity to lead felt like something which was allocated by virtue of time served rather than on merit. To me, starting out in the profession felt like being on the bottom rung of a very long ladder, at the top of which was a modest TLR and a few extra non-contact periods (if you’re lucky).

Fast forward to 2022 and a profession-wide teacher recruitment crisis has renegotiated what leadership means and brought its impact into sharper focus. School leadership has never mattered more. It matters to the students, parents, teachers and the community beyond the gates. Effective school leadership transforms students’ lives and serves a key function in our society as a whole.

However, recruiting effective leaders is a hard job and is getting even harder each year as the recruitment crisis within the profession continues unabated. The need for succession planning at leadership level is becoming a time-sensitive priority. As a profession we cannot afford to wait for teachers to organically evolve into leaders, we need to proactively identify the leaders of the future and invest in them urgently to ensure that schools continue to be wellled.

It is not just about the number of leaders though. In spite of the magnificent work of organisations like #WomenEd we still need more female leaders in our schools, as well as more diversity at leadership level. According to data from the Department for Education’s School Workforce in England survey in 2019, 92.7% of headteachers in the UK were white British, and of the female headteachers (the number of which are disproportionate to the number of women in the profession) were white British.

Furthermore, according to data from NAHT’s Closing the Gender Gap published December 2021, by the age of 60 male headteachers earn £17,334 more than female headteachers. We also don’t retain female teachers who are statistically most likely to leave the profession between the ages of 30 and 39, surely not a coincidence that this coincides with the age at which women are most likely to have started a family. As a profession we seem to be aware of the lack of diversity, but translating this into action is key and is ultimately our collective responsibility.

And although this representation at decision making and policy level is playing catch-up, we as teachers are not powerless to affect change. There is plenty that leaders at all levels – including department heads, pastoral leads and ECT mentors – can do within their own institutions to champion and nurture potential future leaders, including those with protected characteristics, in all sorts of ways.

Role model it:

The easiest way for school leaders to promote leadership is to make it look both achievable and enjoyable. To ‘wear leadership lightly’ and find the joy amongst the pressure and privilege. Positive interactions, frequent small-scale celebrations and humour all go a long way in terms of creating school culture. Leaders set the climate of any school and remaining outwardly upbeat is key to making leadership look appealing to the masses

Communicate it:

Begin by telling your talented ECTs that they have leadership potential, it’s easy to assume that this is a given, but not teachers see themselves as potential leaders. In the fast-paced world of teaching (not to mention the myriad demands of the Early Career Framework) it can often be unsaid that an ECT is brilliant and therefore capable of leading. Frame your lesson feedback and mentor meetings with this in mind and direct staff to the relevant NPQ or other relevant CPD as soon as they’re eligible.