13 minute read

Seneca Review at 50

50

Leaping from One Path of Thought to Another: Seneca Review at 50

Advertisement

by Andrew Wickenden ’09

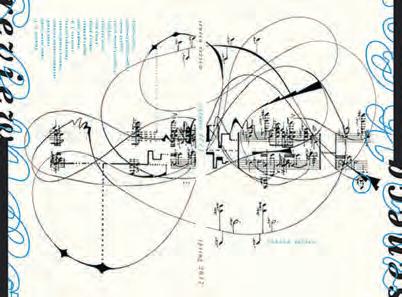

Founded in 1970, Hobart and William Smith Colleges’ professional literary magazine has a long history of innovation and experimentation, publishing important voices, pushing formal boundaries and reimagining the way readers experience literary art for nearly 100 issues. Seneca Review is one of many journals that sprouted up in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and one of just a handful from that era that are still in circulation. From its first issue, the magazine has been publishing some of the most influential and idiosyncratic writers of the past 50 years. Numbering among its many contributors are poet laureates and recipients of just about every prestigious national and international literary prize, including the Pulitzer and Nobel. The 50th anniversary issue, guest-edited by poet Joe Wenderoth, will be published in the spring of 2020. Early Days While the magazine’s early issues included fiction and criticism, the editors’ poetic sensibilities made Seneca Review a vital venue for the surge of writers producing poems in reaction to the scholastic formalism that gripped American poetry after World War II and throughout the 1950s. In the early years, “we had no special editorial slant,” says Professor Emeritus of English James Crenner who, with former HWS English Professor Ira Sadoff, was a founding editor of Seneca Review. But in publishing “exciting new poetry that was being strongly influenced by the likes of Gary Snyder, Robert Bly and John O’Hara, who were helping make American poetry more than a dusty pursuit of academics,” Crenner says the magazine was a vehicle to help get “American poetry out of the classroom and into the fray.” Seneca Review might never have been if not for two students at the time: Joel Rose ’70, a novelist, screenwriter and former editor at DC Comics, and the late Josephine “Josie” Woll ’70, who was an author, editor and professor of Russian at Howard University. They had approached Crenner and Sadoff not only with the proposal for the magazine but with a means to fund it through HWS student governments. As the first issue came together, Rose and Woll independently edited a selection of writing by HWS students that, to their dismay, was relegated to a separate section of the magazine, rather than integrated with the work of established poets and writers; however, the time spent in the Seneca Review office “was the best of my education,” Rose says. “I remember spending hours and hours reading manuscripts and putting the magazine together,” he says. “Josie had a very sharp point of view and we had a good back and forth about our own tastes in literature and what we were trying to do with Seneca Review. I’m not sure we Seneca Review first issue, 1970

The early issues of Seneca Review included notable writers like Robert Bly, Erica Jong, Donald Justice, Heather McHugh, W.S. Merwin and Charles Simic.

expected we’d be able to achieve exactly what we imagined, so much as lay the groundwork for what came later. That the magazine is still going strong 50 years later speaks well of what we were able to achieve.” The early issues of Seneca Review included notable writers like Bly, Erica Jong, Donald Justice, Heather McHugh, W.S. Merwin and Charles Simic. Former President Allan A. Kuusisto P’78, P’81, L.H.D. ’82 was such a fan of the magazine that he included funding for Seneca Review in the annual budget. The thenpresident “loved poetry and poets and took great satisfaction as the review became a firstrate literary journal,” recalls his son, Stephen A. Kuusisto ’78, author, poet, contributing editor at Seneca Review and University Professor and Director of Interdisciplinary Programs at the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University. By 1976, however, Sadoff had taken a job at another institution; the logistics of selecting manuscripts — over several hundred miles, scores of stamps and reams of paper — were taking a toll; and the variety and quality of the submissions had become static. In a letter in that year’s issue, the editors announced the magazine would fold. But “no sooner had we done that than the administration said, ‘Don’t — we want to continue the magazine, it’s good for the school,’” Crenner recalls. It was then that he reached out to a former student, Robert Herz ’70, who had recently earned his M.F.A. in creative writing at the University of Iowa’s famed Writers Workshop, to step into an editorial role. While Crenner remained the nominal editor, Herz reinvigorated the magazine over the course of the next five years, recruiting new voices and imagining new possibilities for a small literary press.

A Window on Today’s Poetry Herz, who today operates the Syracuse-based Nine Mile Magazine and Book Press, says the first issue of the revamped Seneca Review was “a nice mix of older and younger writers (who would become famous or prime in their areas) … We created a new logo for the mag and changed the cover stock and look and feel of the thing. We said in a page-one editorial that running a magazine was like ‘providing a window and a perspective on today’s poetry, a way of treating it as a current event.’”

Over the following years, Seneca Review published special issues, one focusing on the long poem, another on French poetry in translation, another on young poets, which Herz recalls was “the issue that the then-poetry editor of The New Yorker, Howard Moss, told me was one of four books he took with him to California to understand poetry in those days. It was a great compliment — I didn’t know what to say.”

It was also during that time that Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press was formed and began reprinting The Fifties and The Sixties, the dramatic and influential magazine edited by Robert Bly and William Duffy, as well as publishing an anthology of essays by Donald Hall and an innovative hybrid of fiction and poetry by Albert Goldbarth (all of which remain available from HWS Colleges Press). “In my mind we repositioned the magazine and made it vital again in those five years, made it something that people wanted to read again, because we kept serving up new and quality things,” says Herz, though he adds that even in the midst of the magazine’s new ventures, “Jim Crenner was the heart and soul of Seneca Review. No Crenner, no Seneca. Whatever the rest of us did would have been impossible without him.” “I think Jim Crenner was an extraordinary editor and was responsible for getting the magazine off to a great start,” agrees Steve Kuusisto. “If you look at the magazine’s early issues you’ll see remarkable poetry in translation as well as daring and playful work by all kinds of poets. That sense of ‘play’ coupled with literary and aesthetic judgment has continued to define the journal throughout its history.” KUUSISTO ’78

TALL

Dubbed “the renovator-in-chief of the American essay” by critic James Wood, John D’Agata ’95 helped reinvigorate the lyric essay and bring the genre into the literary mainstream. A professor of English and director of the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa, D’Agata is the editor of A New History of the Essay and author of Halls of Fame, The Lifespan of a Fact (with Jim Fingal) and About a Mountain, which The New York Times named one of the 100 best nonfiction books ever written.

The Lyric Essay The magazine continued publishing poems and essays in translation in the early 1980s under guest editors like Kuusisto and John Currie, though its editorial emphasis took on a new texture during the editorship of the late Professor of English Deborah Tall. A poet and essayist, Tall became editor in 1982 and published a number of special issues, featuring new voices in Irish women’s poetry, Israeli women’s poetry, contemporary Albanian poetry, contemporary Polish poetry and an issue dedicated to excerpts from the notebooks of 32 contemporary American poets, which was later published as a book, The Poet’s Notebook: Excerpts from the Notebooks of 26 American Poets. But it is perhaps the 1997 issue on the lyric essay that is Tall’s most significant legacy at the magazine. In that issue’s introduction, Tall and her former student, the essayist and Seneca Review associate editor John D’Agata ’95, wrote what has become the touchstone definition of the genre of the lyric essay, which “forsake[s] narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation.” Tall and D’Agata write that the lyric essay “might move by association, leaping from one path of thought to another by way of imagery or connotation, advancing by juxtaposition or sidewinding poetic logic … [It] sets off on an uncharted course through interlocking webs of idea, circumstance, and language — a pursuit with no foreknown conclusion, an arrival that might still leave the writer questioning.” “The term lyric essay really comes from Deborah,” D’Agata says. “I have a fax from her dated 1996 that’s framed and hanging over my desk to this day in which Deborah first used the term with me as a way of describing a kind of essay whose approach isn’t necessarily argumentative but rather experiential and

immersive, inviting the reader to feel the contours of the writer’s mind as it rolls over the folds of new ideas. These sorts of essays had always existed, of course, but the brilliance of Deborah’s term is how it marries the form to the associative nature of poetry.” Professor of English and Seneca Review coeditor David Weiss, who was married to Tall until her death in 2006, says Seneca Review was “among a number of magazines thinking about the essay in this way, but by John and Deborah giving it a name, it glued the idea of the lyric essay to us. And that’s partly connected with the explosion of and legitimacy of creative nonfiction in the creative writing world. It pulled the essay out of journalism and memoir and gave it a kind of legitimacy in a way that put it on par with fiction and poetry.” D’Agata recalls that 1997 issue of the magazine as particularly momentous — “and not only because we launched that special issue with an actual event at the National Arts Club in New York, but also because its publication was followed by a swarm of excitement, bafflement, conversation and intrigue. It sparked a conversation about just what a lyric essay might be, and by extension what an essay is. But within a year or two of that first issue’s publication, we noticed major publications using the term to describe some new books that perhaps hadn’t been properly categorized before, or perhaps wouldn’t have even been reviewed due to a lack of understanding about what their authors might have been attempting.” Once the “lyric essay” entered the literary lexicon, “more and more writers started trying to bend their minds around the concept … and taking a stab at writing it themselves,” says D’Agata. “The term by no means created the D’AGATA ’95 Seneca Review Lyric Essay, 1997

By staying “true to our history by continuing to break new ground,” the magazine’s future is full of possibility and excitement. — Assistant Professor of English Geoffrey Babbitt, coeditor Seneca Review

form, but instead gave shape to something in the genre that I think both writers and readers felt the presence of but hadn’t entirely understood. So the term sparked new interest in essays in general.”

Seneca Review Books and Beyond This spring, Seneca Review will commemorate 50 years of literary distinction with a celebration on campus, as well as the beginning of a new phase in its history. David Weiss, who has served as editor since 2006, will retire at the end of this academic year and Assistant Professor of English Geoffrey Babbitt, who coedits Seneca Review with Weiss, will take over the role solo. In more than a dozen issues under Weiss’s editorship, Seneca Review has maintained “an openness to new forms and the far reaches of experimentation,” he says. With Kathryn Cowles, associate professor of English and Seneca Review poetry editor, and Joshua Unikel ’07, a contributing editor and designer for the magazine, Weiss developed the 2014 “Beyond Category” issue, which featured a multi-artifact, multi-media, in-print and online extravaganza of writing, music and visual and performance art. Other special issues during his tenure focused on differentlyabled writers and artists, and on essays about the lyric essay.

But perhaps most of all, Weiss has positioned the magazine as a home for writers — writers of the unusual and uncategorizable, yes, but also writers in search of an engaged and invested reader. “There’s an art to being an editor,” Weiss says. “You have to manage to be tactful but forthright, insightful but encouraging. What writers really want and appreciate is useful WEISS COWLES Erica Trabold’s Five Plots, winner of the inaugural Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize.

critique and when you give it, they feel you’re invested in their writing. It’s a rewarding thing, and one of the real pleasures in doing this work.” Babbitt says Weiss’ approach is unusual. “David always writes some type of critical encapsulation of the piece we’re accepting that shows what we like about it,” he explains, “so the writer feels as if we like it for reasons that have been contemplated and really thought about — so the authors feel seen and understood.” Babbitt anticipates building on this editorial style and the omnivorous literary appetite that has become the magazine’s hallmark. Indeed, in 2018, Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press established Seneca Review Books, an imprint founded in 2018 to publish the winners of the Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize Series. Held in conjunction with the Colleges’ Trias Writer-inResidence program, the book prize is a biennial contest to encourage and support innovative work in the essay. Babbitt teaches a course on small press publishing designed around the book prize. In the fall of 2017, students in the course’s first iteration winnowed down submissions to a group of finalists, from which Erica Trabold’s Five Plots was selected and published as the inaugural book in the series. At the end of the fall 2019 semester, a new group of students presented finalists to author Jenny Boully, this year’s judge, who selected Jessica Lind Peterson’s book, tentatively titled Sound Like Trapped Thunder. “The synergy between Seneca Review, the Trias Residency and reading series, and our curriculum is creating a rich new literary culture at HWS — one that provides students with a number of exciting and relatively rare opportunities, including getting hands-on publishing experience, working with famous writers and immersing themselves in the greater literary world. It’s a brilliant place to study writing and literature,” Babbitt says.

By staying “true to our history by continuing to break new ground,” he adds, the magazine’s future is full of possibility and excitement. With student enthusiasm, faculty leadership and — Babbitt hopes — support from HWS alums, he plans to gradually expand the press and develop a robust digital presence for Seneca Review. He and Cowles envision an online archive of multi-disciplinary and hybrid work, for instance, offering a resource for writers, readers, teachers and students interested in hybrid forms. “I think as we step into our next 50 years of publishing, we’ll be expanding the edges of writing to encompass more new, unforeseeable things, which is very exciting,” Cowles says, because after all, “veering out into new territory is part of the history of Seneca Review.” BABBITT

The Senecan Review

In 1957, The Senecan Review — note the extra “n” — was a student-run magazine that has the distinction of being the first joint literary publication of Hobart College and William Smith College. The magazine, which was recently brought to our attention by a letter from its business manager, William Corbett ’59, published two issues of student poetry, prose and art. Today, Thel offers students an outlet for students to publish their original literary work.