12 minute read

Understanding SEL

By Theresa Kelly Gegen

HHow are you feeling?

Emotional wellness includes managing life’s daily stresses, the ability to get along with others, adapting to change, and overcoming life’s difficulties, large and small. In times of normalcy as well as times of turmoil, emotional wellness gets us through the days.

How are students feeling?

Children need emotional wellness, in school and beyond, and they develop emotional wellness as they grow, which they do in times of normalcy and times of turmoil.

Social and emotional learning (SEL) brings emotional wellness into schools, with intentionality, in systems and structures designed to help students learn and grow beyond (yet with) math, language arts, sciences, and social studies. As with academic learning, what students need under the umbrella of SEL varies as much as the individuals themselves. SEL aims to manage that umbrella through storms universal to personal, integrating SEL into the curriculum while considering impacts on academic success, equity, and school safety.

An article discussing school safety and security measures in the wake of school shootings, “Does It Make More Sense to Invest in School Security or SEL?” by Diana Anthony noted that, “Social and emotional skills are like any skills, in that students need daily practice to stay sharp. To make room in the crowded school day for this daily practice, SEL needs to be woven into the culture and curriculum of a school.”

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) was formed in 1994 to establish high-quality, evidence-based SEL “as an essential part of preschool through high school education.” At that time, schools and schoolchildren were presented with a wide but uncoordinated range of “positive youth development programs such as drug prevention, violence prevention, sex education, civic education, and moral education, to name a few.” All of these

programs were SEL, and in the late 1990s SEL developed as a framework to address the needs of young people and align and coordinate the programs. CASEL and others have built that framework, and CASEL’s work includes advancing the science of SEL to expand high-quality, evidence-based SEL practice, and to improve state and federal policies in the areas of SEL.

There are skeptics. Some believe schools are solely for academics, especially when time and resources are limited. Others say SEL has merit but belongs outside the classroom. Expectations are enormous; misses can be tragic. Even with evidence-based standards and benchmarks, SEL accountability and evaluation can be elusive.

However, implementation and research over the past three decades are establishing SEL as a vital portion of the whole, towards the goal of academic and life success for all students. A landmark 2019 study From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope, developed by the Aspen Institute, joined by CASEL and leaders in education, research, policy, business, and the military, has sparked the current wave of assessing the value of SEL, noting “the movement dedicated to the social, emotional, and academic well-being of children is reshaping learning and changing lives across America.”

CASEL defines social and emotional learning as “the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

Why?

The rationale for social and emotional learning starts, of course, with genuine hope for students to be emotionally well. SEL aims to increase confidence, security, community, responsibility, and resiliency in students. The standards and benchmarks are tools to create practices and give measurement, to improve the emotional wellness of every student. SEL is student-centered, of course, but with benefits that radiate to the school and community. It includes topical issues such as bullying, peer pressure, stress, abuse, and mental health. Furthermore, there is urgency in identifying students experiencing mental or emotional turmoil that might not otherwise be addressed, in hopes of averting tragedies involving self-harm or serious harm to others.

Beyond mental health issues, SEL develops students with decision-making, goal-setting, time management, and study skills, plus the ability to make healthy choices. Research has established that fully integrating SEL with the academic curriculum leads to improved academic performance, more engaged students, increased likelihood of graduation, and proceeding to college and careers. According to the work of the Aspen Institute’s National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, “students with healthy social and emotional development are more successful in the workforce and experience greater lifetime well-being.”

Integration

In Illinois, “social and emotional learning … is the process through

which children develop awareness and management of their emotions, set and achieve important personal and academic goals, use social-awareness and interpersonal skills to establish and maintain positive relationships, and demonstrate decision making and responsible behaviors to achieve school and life success,” according to the introduction to the Social and Emotional Learning Standards established by the Illinois State Board of Education.

The SEL metamorphosis began in Illinois in the early 2000s. Illinois was among the first states to develop standards: In 2003 SEL joined math and language arts among standards required for all K-12 students. Illinois’ Social and Emotional Learning Standards are built upon three goals: • Goal 1 – Develop self-awareness and self-management skills to achieve school and life success. • Goal 2 – Use social-awareness and interpersonal skills to establish and maintain positive relationships. • Goal 3 – Demonstrate decision-making skills and responsible behaviors in personal, school, and community contexts.

The goals lead to a set of 10 learning standards, which “define the learning need to achieve the goals. The standards, in turn, have benchmarks that specify developmentally appropriate SEL knowledge and skills for each standard, defined in stages and in grade-level clusters. The benchmarks drill down to performance descriptors further aligning the standards to curriculum, classroom activities, and assessments.

For example, Illinois SEL Goal 3 is “Demonstrate decision-making skills and responsible behaviors in personal, school, and community contexts,” acknowledging that “Achieving these outcomes requires an ability to make decisions and solve problems by accurately defining decisions to be made, generating alternative solutions, anticipating the consequences of each, and evaluating and learning from one’s decision making.” Within that, Standard 3B is to “Apply decision-making skills to deal responsibly with daily academic and social situations.”

For example, a third-grader is facing a math problem set. The lesson plan includes instruction in how to solve those problems. Integrated SEL might come into play when the student struggles to solve the math problems. How does the student decide what to do? Does the student know what resources are available? Does the student know when, to whom, and how to ask for help? An SEL lesson plan example includes “I can’t do this” strategies, such as developing methods that encourage students to ask for help from their

peers, reframing mistakes as opportunities for learning, and adding one word to the child’s coping mechanism, “I can’t do this … yet.”

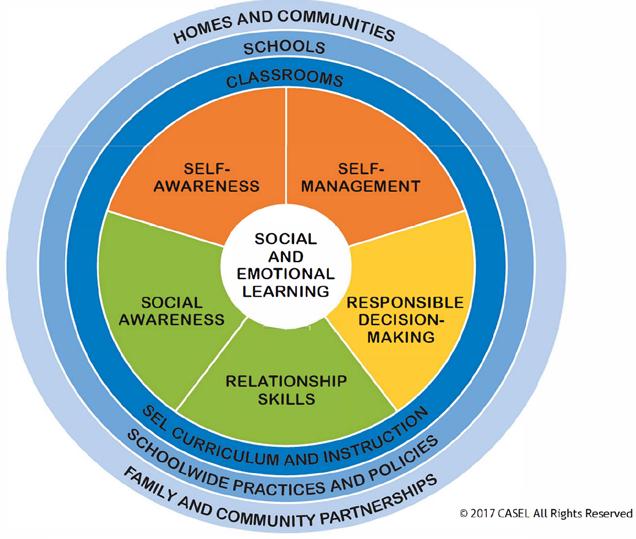

CASEL focuses on five core competencies of SEL (see page 16): Self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.

As the work of CASEL explains, “When fully implemented, SEL is infused throughout every students’ school day, in every interaction and setting. This means SEL must be seamlessly embedded throughout all practices and policies that affect students’ experience in schools, including academic content and instruction, discipline systems, and the continuum of academic and behavioral supports that the district offers.”

Districts use the standards to develop their own SEL umbrellas, including modeling appropriate SEL practices and through academic instruction, discipline policies, and student supports to create a continuum of SEL for everyone.

In 2013, Naperville CUSD 203 partnered with CASEL as a

focus district and developed vision, mission, and belief statements to guide SEL work. Starting with its elementary schools and moving now into the upper grades, the district’s strategic plan included: • Building a comprehensive professional learning plan to build knowledge and expertise of the core components of SEL for all teachers, administrators, and staff; • Actively engaging parents in the learning and supporting of SEL in the home; • Developing a comprehensive curriculum that includes explicit instruction and systematic integration of skills into content; and • Ensuring each classroom and school has a positive climate and culture.

The district created an assessment tool based on priority standards for each grade level and created performance-based rubrics to measure proficiency. Notably, the Naperville team used measurements of “beginning,” “approaching,” and “secure,” deliberately avoiding an “exemplary” category, stating “our main goal is to ensure students are secure in these skills and not to extend or enrich learning experiences beyond the standards.”

Another CASEL focus district has been Chicago Public Schools. With extensive SEL programs at all levels supporting 200,000 students, CPS reported a high school graduation rate increase from 59.3% in 2012 to 77.5% in 2017, out-of-school suspensions declining 76%, in-school suspensions decreasing by 41%, and expulsions dropped by 59% since the 2012-2013 school year.

Over the past decade, many key developments in Illinois public education have a nexus in SEL, which covers facets of career and technical education, early childhood education, language acquisition, special education, nutrition and meals, assessments, and equity and is encompassed in the development of ISBE’s “Whole Child, Whole School, Whole Community” concept.

SEL and the Community

Social and emotional learning is a lot. The standards are extensive, every child is unique, every district is different, and the implications are enormous. Schools and families obviously carry much of this responsibility. In the past decade the SEL umbrella has grown, increasingly combining community resources with the school district’s efforts to expand SEL beyond the home and the classroom. CASEL notes that community partnerships involving daycares and before- and afterschool programs, community-based nonprofit organizations, health care providers, including mental health care, colleges and universities, local community foundations, other governmental units, and local businesses can support school-based SEL when students • “Participate in cross-age peer tutoring and self-directed activities that build their self-management and help them make new friends, learn about their communities, and participate in service learning (social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making). • Interact with people of varying backgrounds, ages, concerns, and priorities (understanding, empathy, and cultural awareness). • Contribute to the larger community (social awareness and responsible decision-making). • Gain mentorship from a caring adult (relationship skills).”

In this wave of SEL development, school districts are being encouraged to create SEL programming that reflects the values and norms of their communities, solicit the community’s participation, and further to join community partners in aligning “efforts, expectations, shared agreements, and language used for social and emotional learning, and sharing practices that contribute to a positive environment,” according to CASEL’s Guide to Schoolwide SEL.

Recommendations

In a 2020 survey by the Illinois Association of School Boards, SEL was ranked — by school board members, superintendents, and other school personnel — as the issue of highest urgency in their school districts. School officials understand that even times of normalcy might not be calm for students, and times of turmoil will influence students in different ways. Developing social and emotional competencies is of tremendous value. With the Illinois Social and Emotional Learning Standards in place, school districts and their communities are exploring, planning, and developing local capacities for SEL. Here are recommendations for Illinois school board

members taking a special interest in SEL: • Understand the Illinois Social and Emotional Learning Standards and what instruments the district is using to measure SEL. • Learn what the district has in place, considering local resources, needs, and stakeholder input. Know what’s coming next in the district’s SEL journey. • Consider professional development opportunities and for administrators, teachers,

and staff, especially guidance on how to implement and integrate SEL. • Review school board policy on the topic. PRESS subscribers can refer to PRESS

Sample Policy 6:65, Student

Social and Emotional Development, which includes methods for the incorporation of SEL objectives. • Support best practices for behavior management, discipline, and school climate that promote healthy, safe, and nurturing environments for all students. • Consider a deeper dive into the SEL resources presented here (see note below).

As school boards understand the importance of SEL, consider this, as noted in From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope, “The promotion of social, emotional, and academic learning is not a shifting educational fad; it is the substance of education itself.”

Theresa Kelly Gegen is editor of the Illinois School Board Journal. The SEL resources mentioned in this article, and many more, can be accessed starting at bit.ly/JA20Jres.

The National Scope: Recommendations for Action

The Aspen Institute, joined by CASEL and a host of educators and leaders in research, policy, business, and the military, formed the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, to study research, practice and policy. In 2019, the commission published, “From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope” which offers these recommendations with a wealth of supporting documentation and explanation. The recommendations seek to accelerate efforts in states and local communities by strengthening six broad categories that impact student outcomes.

Set a clear vision that broadens the definition of stu

dent success to prioritize the whole child. This begins by articulating the social, emotional, and academic knowledge and skills that high school graduates need to be prepared for success in school, the workforce, and life.

Transform learning settings so they are safe and sup

portive for all young people. Build settings that are physically and emotionally safe and foster strong bonds among children and adults.

Change instruction to teach students social, emotional, and cognitive skills; embed these skills in academics and

schoolwide practices. Intentionally teach specific skills and competencies and infuse them in academic content and in all aspects of the school setting (recess, lunchroom, hallways, extracurricular activities), not just in stand-alone programs or lessons.

Build adult expertise in child development. Ensure educators develop expertise in child development and in

the science of learning. This will require major changes in educator preparation and in ongoing professional support for the social and emotional learning of teachers and all other adults who work with young people.

Align resources and leverage partners in the com

munity to address the whole child. Build partnerships between schools, families, and community organizations to support healthy learning and development in and out of school. Blend and braid resources to achieve this goal.

Forge closer connections between research and practice by shifting the paradigm for how research gets

done. Bridge the divide between scholarly research and what’s actionable in schools and classrooms. Build new structures — and new support — for researchers and educators to work collaboratively and bi-directionally on pressing local problems that have broader implications for the field. —The Aspen Institute, et al. From a National at Risk to a Nation at Hope.