6 minute read

The Idyllic Plan of the Camel Corps

“Camels” by Bill Arhendt

Transportation was a perplexing problem in the Southwest during Pueblo days. The following is the story of one idealistic but unsuccessful plan devised to solve it... The Camel Corps.

The history of the “Forgotten Camel Corps” is a riveting chronicle. According to Bonsall, biographer of General E. F. Beale, the idea of using camels came to Beale while exploring Death Valley with Kit Carson. The war department was at the time struggling with difficulties of Army transportation in the arid regions of the Southwest. When Beale presented himself at the department with his suggestion of a camel corps, it was regarded as impractical. But all events having as much substance as a relayed line of balloons were, at this time, warmly advocated for the same purpose.”

The matter was discussed in Congress, and in 1854 Jefferson Davis introduced a bill for an appropriation to purchase camels – which failed to pass. In 1855 the Los Angeles Star said editorially;

“We predict that within a few years these extraordinary and useful animals (camels) will be browsing upon our hills and valleys, and numerous caravans will be arriving and departing daily. Let us have the incomparable dromedaries, with Adam Express Companies men, arriving here tri-weekly with letters and packages in the five or six days from Salt Lake and 15 or 16 days from Missouri. Then the present grinding steamship monopoly might be made to realize that the hardworking miner, the farmer, and the mechanic were no longer entirely within their grasping power.”

We might have an Overland dromedary express that would bring us the New York news in 15 to 18 days. We hope some of our energetic capitalists or stockbreeders will take this speculation in hand, for we have not much faith that Congress will do anything in the matter.”

This has a familiar sound, even though written in 1855. Despite the Stars pessimism, however, Congress did, under the Davis administration as War Secretary, made an appropriation of $30,000 to buy camels. An Army transport, The Supply, under the command of Colonel David Porter, was promptly dispatched to Egypt and Arabia. Beale’s biographer says that Porter first stopped at Tunis and bought two camels as an experiment; then, he went to Constantinople, where he met British officers who told him of the valuable service rendered by their camel corps of 500 animals used in the Crimean campaign. After this, he purchased 33 camels, which he landed at Indianola, Texas, then made a second trip, returning with 44 “very sea-sick camels.”

In February 1857, the animals were brought across the country to Albuquerque, where they were divided, part being sent to San Antonio, where they were to be used as transport animals by the troops in southern Texas. The balance, under the charge of Lieutenant Beale, accompanied by 44 citizens and 20 soldiers, were dispatched to Fort Tejon, California.

In July 1857, Beale reported to the Honorable J. B Floyd, Secretary of War, regarding the camel corps:

“We had them on this journey sometimes 26 hours without water and exposed to a great degree of heat – the mercury standing at 104 – and when they came to water, they seemed to be almost indifferent to it, not all drinking and those that did, not with the famished eagerness of other animals when deprived of water the same length of time.”

Beale had been detailed to do a new survey for a wagon road between Fort Defiance, New Mexico, and Fort Tejon, California. After reaching Fort Tejon, he reported;

“An important part in all our operations has been affected by the animals without the aid of this noble and useful brute, many hardships which we were spared, would have fallen to our lot, and our admiration for them has increased day by day. Some new hardships patiently endured, more fully developed their entire adaption and usefulness in the exploration of the wilderness. One of the most painful sights I ever witnessed was a group of mules standing over a little barrel of water and trying to drink from the bunghole, frantic with distress and eagerness to get at it. The camels seem to view this proceeding with great content and kept on browsing on the grass and brush.”

The enthusiastic officer declared that he would rather handle 20 camels then five mules and contrasted the loading of the patiently kneeling camel with that of a restless, kicking mule. The advantages of a thirst-proof beast that can also supply its own rations when necessary are obvious. Also, it is reported that on the trip from Fort Tejon to the Colorado River by way of Los Angeles, “each animal was packed with 1000 pounds of provisions and military supplies. With this load, they made from 30 to 40 miles per day, finding their own sustenance in even the most barren country and going without water – the largest ones can pack a ton and travel (light) 16 miles an hour.”

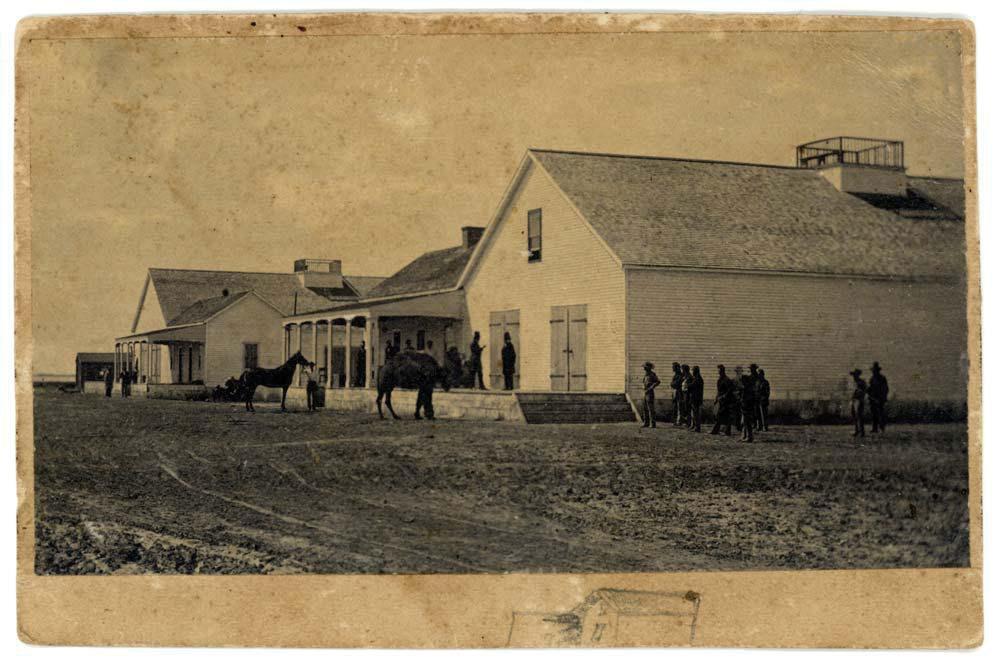

Only known surviving photo of the U.S. Camel Corps. The photo is captioned, A member of the legendary southwestern ‘Camel Corps’ stands at ease at the Drum Barracks military facility, near California’s San Pedro harbor.”

Theoretically, the camel should have proved a God-send to the Army and the country. But as a matter of fact, the experiment turned out a most dismal failure. Soldiers, and more important still, horses and mules, exhibited a deep-seated antipathy to these ships of the desert. Other animals bucked and vamoosed at the site of the humpback strangers. Men detailed to assist the two camel drivers, High Jolly and Greek George – both of whom were well known in Los Angeles – deserted rather than wait on the camels. Mexicans and professional “mule skinners” had no use for animals that didn’t kick back nor understand their brand of “cussing.” The camel possesses a most ferociouslooking set of teeth, which “it exhibits” with a roar like that of a Royal Bengal tiger – yet they are entirely harmless.” The soldiers and drivers were afraid of them, they claimed. They mistreated the brutes so that many of them died.

Perhaps the fault was not entirely with the drivers, however. The camel could make good time under a load – when he was turned loose to forage on a terrain where one mouthful might be scattered over an acre of ground, he could make even better time. Tired herders often had to spend most the night rounding up the stray animals. J. M. Gwinn says, “Of all the naughty, perverse and profanity provoking beasts of burden that ever trod the soil of America, the meek, mild-eyed, and soft-footed camel was the most exasperating. That prototype of perversity, the Army mule, was almost angelic in disposition compared to the humpback burden-bearer of the Orient.”

Perhaps the camel was homesick! At any rate, when the war ended, the powers-that-be decided that camels could not be utilized to advantage, condemned those remaining, and put them up for sale at Benicia. Beale’s biographer says that the General purchased some of them and kept them on his Tejon Rancho. He tells a story of Beale driving with his son, a tandem team of camels to Los Angeles – a trip that would have delighted the heart of any small boy.

A couple of Frenchmen bought the remainder and took them to a Rancho on the Reno River in Nevada. Here they were used in transporting salt to Virginia City until the coming of the railroad gave more convenient shipping facilities. The drove, which had increased to 25 or more, was then moved to Arizona and used to pack ore from the Silver King Mine to Yuma. Eventually, the beasts were turned loose on the desert near Maricopa Springs to shift for themselves. For years afterward, stories of the unusual appearance of camels, frightening travelers, and animals almost into fits were frequent. Many of the camels were killed by freighters because of the stampedes caused among the pack animals or mule teams. The Indians, too, were much afraid of the strange creatures and never missed an opportunity to slaughter them. In the 80s, a number of them were captured and shipped east for exhibition purposes.