6 minute read

Geronimo: Still A Prisoner of War

The old Apache warrior is still being regarded as a prisoner of war by the US Army, even though he has been dead for many years.

Before he died in 1909, Geronimo’s fondest hope was to return to the mountains of Arizona. “There is no climate or soil which, in my mind, is equal to that of Arizona,” he said in 1906.

Geronimo in a 1905 Locomobile Model C, taken at the Miller brothers’ 101 Ranch located southwest of Ponca City, Oklahoma, June 11, 1905.

“It is my land, my home, my father’s land, to which I now ask to be allowed to return. I want to spend my last days there and be buried among those mountains. If this could be, I might die in peace,” he added. Throughout his long captivity, Geronimo had made constant pleas to government officials to be returned to the mountains where he lived in Arizona.

Ordinarily, Apaches do not move their dead, but the Indians at Fort Apache still claim that Geronimo was not given a proper Apache burial in 1909. When Geronimo was interred at the Fort Sill Cemetery, Apache leaders say that the Army did not permit those conducting the burial to use many of the traditional cultural preparations.

White Mountain Apache tribal chairman Ronnie Lupe said, “We would like to be able to provide those types of services for our great chief so that he can receive the blessings from us here on earth and so that he will have an open door on the other side of the world.”

Many of the Oklahoma Apaches are direct descendants of the original Chiricahua band that was forced into exile in 1886. Their leaders say that they are prepared to fight any effort to remove the old warriors’ body from the Fort Sill Cemetery.

Going back to the mood of the country and its leaders at the turn-of-the-century, it is obvious why Geronimo’s request to return to Arizona was denied. The feeling then was that if they allowed the Indian prisoners of war to return home, they would return to the old way of life and began raiding nearby settlements again.

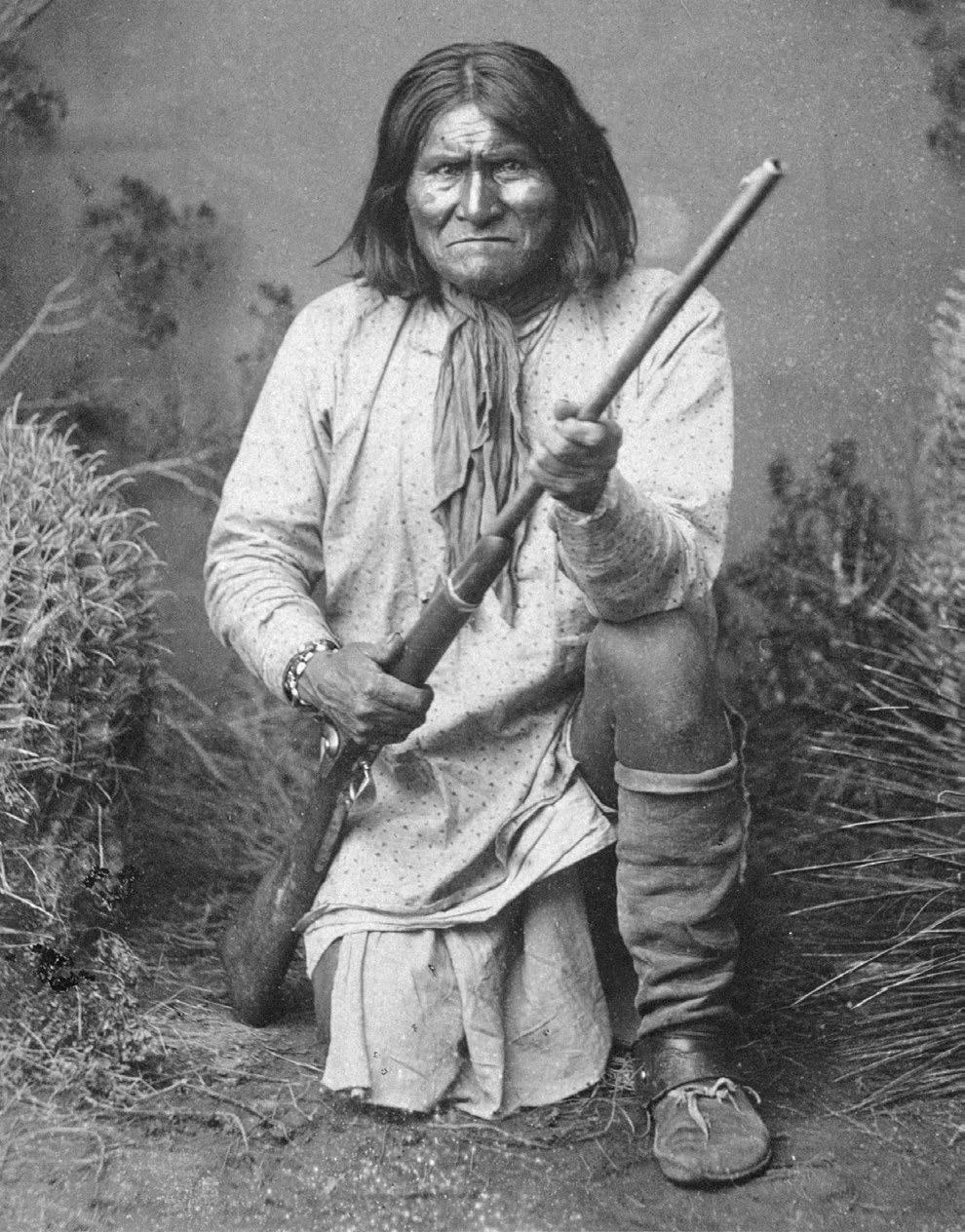

Geronimo (Goyaałé), a Bedonkohe Apache, kneeling with rifle, 1887.

First Lieutenant George A. Purington, the commanding officer of Fort Sill in 1905, said at the time that Geronimo and other members of the Chiricahua Apaches would not be returned to their homeland because of “the many deprivations committed by Geronimo and his warriors and the enormous cost of subduing them. The oldage Apache deserves to be hanged.”

Geronimo, during his later years, spent a great deal of his time trying to convince anyone and everyone that he should be allowed to return home. When he met General Nelson A. Miles at the Omaha World’s Fair in 1898, he accused his adversary of lying to him to obtain his surrender and the surrender of his followers. Miles had promised Geronimo that he would eventually be allowed to return to his homelands.

General Miles, as the story goes, admitted that he had lied; pointing out that what was good for the goose was good for the gander. “You lied to Mexicans, Americans, and your own Apaches for 30 years. White men only lied to you once, and I did it.”

Geronimo smiled and begged once again to be allowed to return home. “The acorns and pinion nuts, the quail and the wild turkey, the giant cactus, and the Palos Verdes,” he said “they all miss me, I miss them too. I want to go back to them.”

Portrait of Geronimo by Edward S. Curtis, 1905.

Miles was adamant, “a beautiful thought, Geronimo, quite poetic. But the men and women who live in Arizona - they do not miss you. Folks in Arizona sleep now at night. They have no fear that Geronimo will come and kill them.” Even though Miles had rebuffed his appeal, Geronimo never stopped yearning to return to the Gila River Canyon, where he was born. In 1905, Geronimo brought over his request directly to the president of the United States. A few days after Teddy Roosevelt was inaugurated, Geronimo applied for and received permission to see the president. “Great father,” Geronimo said, “other Indians have homes where they live and can be happy. I and my people have no homes. The place where we are kept (Oklahoma) is bad for us.” “We get sick there and die. White men are in the country that was my home. I pray to you to tell them to go away and let my people go there and be happy,” he said.

Geronimo as a U.S. prisoner in 1905.

But Roosevelt refused even to consider the proposal. “Geronimo,” he said, “there would be more war and more bloodshed. It is best for you to stay where you are. That is all I can say, except that I am sorry, I have no feelings against you.”

Geronimo died on February 19, 1909, of complications caused by drinking whiskey. Although it was a capital offense at that time to sell liquor to Indians in Oklahoma, Geronimo and another man somehow obtained a bottle of whiskey in Lawton, Oklahoma..

They drank the whiskey on the way back to the fort and slept off its effects on the ground during a freezing rain: when he awoke the next morning, Geronimo was coughing and complaining that he had been sick all night. He was rushed to Fort Sill hospital, but he died the next day of pneumonia. The old war chief was approximately 80 years old and still considered a prisoner of war.

In 1913 the remaining Apache prisoners were finally released. Even though they were not permitted to return to Arizona, they were granted passage to the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico.

At first, it seemed that the Chiricahua’s were destined to remain in Oklahoma forever. Several official government documents clearly stated the Indians were to remain at Fort Sill as prisoners of war. The government was also reluctant to initiate another Indian removal program. Still, eventually, federal negotiators were able to work out a solution to the problem whereby the Apaches could choose either to live on the Mescalero reservation or to purchase individual lots in Ojo Caliente, the side of the old Chihenne reservation that has since been opened to the public. Most of the former prisoners of war opted to go to New Mexico, but some settled along Lake Ellsworth about 10 miles from Fort Sill.

Fort Bowie was established in 1862 to protect the Butterfield stage route across Apache pass and to pacify the Apaches in southern Arizona. The fort was abandoned in 1894 when there were no more Indians to fight. The ruins of the old Fort Bowie was declared a national historic site in 1972.

Geronimo may yet return. Pressure from a large number of interested people may well force the government to send Geronimo’s body back to Arizona.

Edgar Perry, director of the White Mountain Apache cultural center, says there are 9000 Indians at Fort Apache who still practice old Apache traditions and remember Geronimo. They want him back, he said.

And it was also the will of Geronimo – – “I want to be buried among those mountains… My heart is no longer bad,” he said.

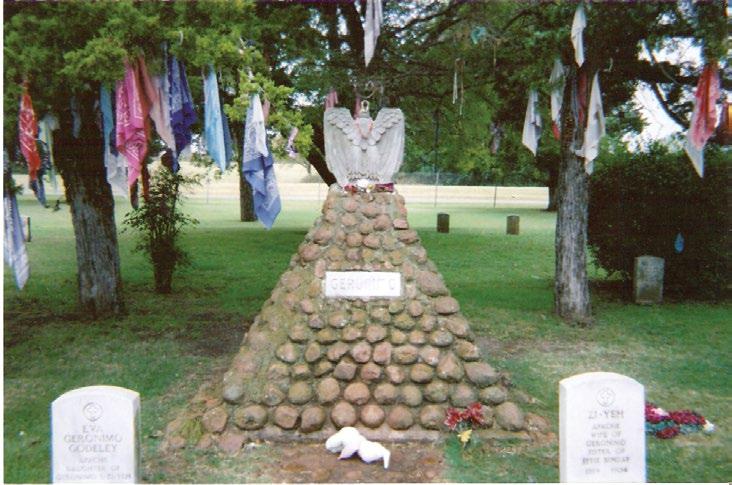

Geronimo’s grave at Fort Sill, Oklahoma in 2005.