6 minute read

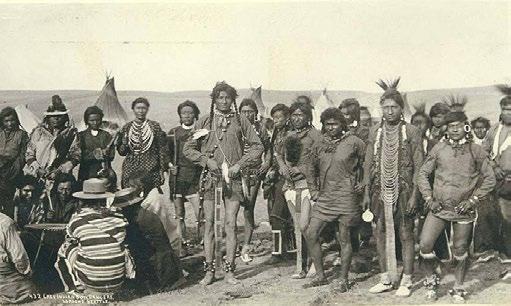

The Sioux Dance...

A Ceremony of Self-Torture

Due to its gruesome aspect, the “Sun Dance” of the Sioux has received much attention from historians, however, almost identical ceremonies were held by every tribe of the plains. All were predicated on the custom of self-torture as a means of expressing their devotion to the good God.

Before and immediately following the arrival of the white man, the medicine ceremonial was of the greatest significance, but as “civilization” made inroads among the tribes, the ritual faded from a brutal ordeal to a routine celebration.

THE ORIGIN

The medicine dance and ceremony evolved naturally because of three basic circumstances and character traits among the early, wild Indians. First, it provided a very expressive means of demonstrating their deep religious faith (or what “civilization” people term “superstition” when such faith is applied to a religion other than the one they believe in).

Secondly, throughout history, demonstrations of religious faith have been most brutal among the least civilized people gladly accepted any accompanying torture with no reservations that reason might impose.

Thirdly, among all worldly people of the early days, the American Indian was bestowed with the most significant physical prowess and endurance and welcomed the opportunity to demonstrate his strength in a display of devotion to his God.

PERFORMANCE OF THE ORIGINAL MEDICINE DANCE

The medicine dance and ceremony among the early tribes of the plains were held about once a year under the close supervision of the Medicine Chief, in a large unique built structure that housed the main arena some 20 feet in diameter. After all neighboring tribes and bands were summoned to a great”camp meeting,” the Medicine Chief selected the dancers, usually in a ratio of one warrior for every hundred persons of his band in attendance. He then chose the “guards” who were to surround the dancers and assure the proper functioning of all aspects of the rituals.

At a specified time, the dancers, stripped to their breach cloths, were escorted to the arena and assembled in a circle facing a small doll effigy suspended from the top poles of the Lodge. One side of the hanging doll was white, representing the good God, and the other was black, indicating the presence of the bad God. Each dancer was furnished a whistle of bone or wood that he would be required to hold in his mouth for the duration of the dance. Upon the signal to commence, each dancer, with his eyes fixed on the suspended image, began to slowly encircle the arena, blowing continuously on the whistle at the same time. The will of the Gods would be determined by the endurance of the dancers to continue their monoto- nous encircling without stopping for food, water, or other reasons. After 8 to 10 hours, the slow rotary motion, the constant fixation of their eyes on the dangling doll, and the expenditure of breath and the unceasing whistling began to take its toll. By this time, a large crowd had gathered in anticipation of the first dancer to reel, tumble, and fall.

And soon it happened. The first dancers to fall were dragged aside, where they were sloshed with”medicine paint.” If this failed to bring them around, they were doused with icy water. When they regained consciousness, it was the pre- rogative of the Medicine Chief to determine whether or not they be ordered back to continue their ordeal. This decision was generally influenced considerably by promises of gifts to the medicine man by friends and relatives of each exhausted dancer. Unless the Medicine Chief had personal reasons to the contrary, follow- ing dancers were usually excused, since returning them might prove fatal, and the death of a dancer indicated that supremacy of the bad God, or”bad medicine” for all parties and members of their bands.

But there were many cases where the following dancers failed to respond to either the medicine paint or the cold water treatments. In such cases, pande- monium broke out, and all in attendance departed as quickly as possible in their attempt to escape the wrath of the bad God.

If no fatalities marred the ritual, it often continued as long as 72 hours before the Medicine Chief concluded the good God was satisfied with the performance, and mercifully ordered an end to it. By that time, dancers were still able to con- tinue their remarkable display of physical endurance.

THE CEREMONY OF SELF-TORTURE

After the medicine dance was over, and sometimes before, the medicine cer- emony began. Both were extreme demonstrations of religious devotion. Those who endured the exhausting monotony of the medicine dance for the longest time displayed their supreme devotion, while those who release themselves from the torture of the medicine ceremony in the shortest period expressed the most significant divination. Because of this time factor, more fatalities (indicating “bad medicine”) occurred among the participants of the dance, then the ceremony, although the latter was far more bloodied and brutal.

Cheyenne Sun Dance

Unlike the dance, participants in the ceremony were volunteers – usually among the young men of unbounded enthusiasm and energy. These men, who recognized that until they unflinchingly withstood the ordeal of the medicine rituals, they were not “initiated” into the status of a man, a full-fledged warrior, and a “priest” who was qualified to make his own medicine.

THE PROCEDURE

At the appointed hour, each volunteer was summoned by the Medicine Chief, who, after determining that he was physically able to withstand the upcoming torture (his failure to do so would mean “bad medicine”), began the gory preparations. With a broad-bladed knife, vertical incisions were made about 2 inches apart and from 3 to 4 inches long through the pectoral muscles in each breast. The flesh between the incisions was lifted, and a horsehair rope inserted under it. Wooden pegs were attached to one end of the rope, and the other free end was secured to the top Lodge poles, allowing about 10 feet of “play.”

From that point on, it was a matter of how long it would take the young men to release himself through vigorous contortions and individual effort that would tear away the incised muscles. This feat ranged from immediate to several days in dura tion, during which time he was given no food or water, or allowed periods of respite for any reason.

The quicker the release is achieved, the better the medicine, and the better the postoperative treatment by members of the tribe. Should the participant flinch or cry out under the knife, or show evidence of weakness during the subsequent period of torture, he was released at once, and sent away in disgrace. In the earliest times, he was condemned to”be as a woman” and could not hold property or marry, and was contemptuously forced to do a woman’s work.

There were many variations of the first ritual procedures. Often the incisions were made in the muscle of the shoulder blades or back, and the free end of the rope attached to heavy, movable objects. Sometimes the participants were pulled up by the ropes until 6 to 8 feet off the ground, and left to dangle until his weight and contortions tore away the flesh, dropping him to the floor of the arena.

Cree Indian Sun Dancers.

On the occasion of an individual, for one reason or another, wanting his private ritual, the most difficult circumstances were arranged. The free end of the rope was attached to a pliable pole placed in a bent position. When the polls released to its normal straightened position, it yielded to every effort of the warrior to free himself. Often this ritual of self-inflicted torture lasted for days until the tissue softened to their breaking point.