6 minute read

Wonder Women of WWAMI

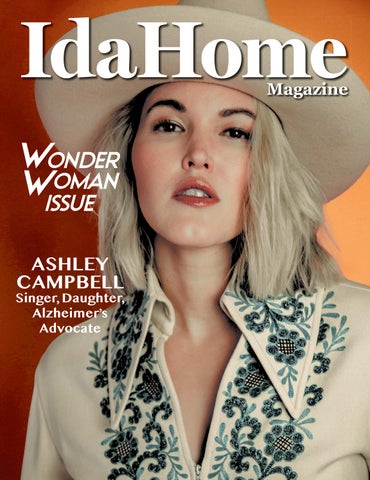

Protestors gathered at the Idaho State Capitol to rally for reproductive rights. Since the near total ban on abortion, doctors are leaving the state. PHOTO BY KAREN DAY

Female medical educators and students are working to ensure a solid future for Idaho patients

BY JODIE NICOTRA

When she was an undergraduate at Washington State University, Bailey Vail discovered a passion for supporting people with mental illness. After graduation, she continued this work in Boise, Idaho, as a case manager, helping people with mental illness rebuild their skills and learn to participate and thrive in society.

Only then did Vail discover the severe shortage of psychiatrists in Idaho. This discovery was one of the reasons she applied to the University of Washington School of Medicine’s (UWSOM) WWAMI program for medical school.

A unique medical education program, WWAMI stands for the states in partnership with UWSOM: Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho. WWAMI partners with the University of Idaho to provide access to public medical education to the citizens of Idaho. This partnership is key to bolstering the number of physicians in Idaho, especially in rural areas.

Residents like Vail embody hope for the future of medical practice in Idaho, which according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, ranks 49th in the country for the number of physicians per capita.

But that’s not Idaho’s only shortfall. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the state also has the lowest percentage of women physicians in the country—just 26%, compared with 37% nationwide.

This gender imbalance makes a difference. A 2021 Pediatrics article cited several studies testifying to the unique strengths of female physicians. Compared to their male counterparts, women are more likely to follow clinical guidelines, focus on preventive care, and build partnerships with their patients. Statistically, these factors tend to make for better patient outcomes.

Mentorship of female medical students is critical to their success. And despite Idaho’s gender imbalance, it has some powerful female leaders working to secure the future of medical education in the state.

Mary Barinaga, MD, assistant clinical dean for WWAMI and clinician at Full Circle Health in Boise, works with doctors all over the state to set up medical student rotations.

“I’m kind of a talent scout,” said Barinaga, who is also a WWAMI alumna. “I’m looking for doctors in this state who are passionate about teaching the next generation of doctors.”

Barinaga has her work cut out for her. As the Idaho Capital Sun reported, recent legislative actions and governmental interference in the practice of medicine affecting care of pregnant women in Idaho are among the factors causing doctors to depart.

“We’ve seen this really have a profound effect in the last year where providers are leaving the state, especially doctors who take care of women,” Barinaga said. “We’re seeing hospitals decide not to deliver babies anymore, and hospital systems where all their maternal fetal medicine and OB specialists are leaving the state. And that really has me worried for the patients and citizens of Idaho.”

In her new role as president-elect of the Idaho Medical Association, Barinaga advocates for physicians and patients across the state to be able to continue practicing evidence-based care.

“I look forward to working with our legislators in trying to find solutions to help keep a strong physician workforce in the state and help families and communities in Idaho keep access to high quality care,” she said.

Educating the Next Generation of Idaho Doctors

Another Idaho-based WWAMI alumna, Paula Carvalho, MD, sees attracting and keeping residents in Idaho as key to bolstering the medical workforce.

“If you train in a residency program in a community, you’re pretty likely to stay there,” Carvalho said. “So to attract doctors to Idaho we need to have more rotations for clerkships for third and fourth-year students and more residencies in family medicine and specialists.”

As academic section chief of pulmonary critical care at the Boise VA Medical Center and director of the clerkship program at the hospital, one of Carvalho’s main educational goals is to ensure uniform education across different WWAMI sites.

“We want the student in Wyoming to get the same caliber of education as the student in Seattle or the student in Fairbanks, Alaska,” Carvalho said.

Carvalho and others from the simulation program at the University of Washington created a lab at the Boise VA, where students can practice medical procedures on robots before trying them on real patients.

“It’s a fascinating science, simulation,” Carvalho said. “And you don’t hurt anybody. So when a student says ‘Well, we should do this as the next step in this emergency,’ the teacher can say ‘Go ahead, try it out.’ If it doesn’t work, they’ll find out, but in a way that hasn’t hurt a patient.”

Training a Rural Medical Workforce

For a state like Idaho, where 35 of 44 counties are rural, trained physicians who practice rural family care are critical to creating better healthcare outcomes for patients. Several recent studies highlight the importance of recruiting female doctors, especially to rural care, where relationship-building is key.

WWAMI’s TRUST (Targeted Rural Underserved Track), which aims to create a workforce of rural physicians, is one such recruiting tool.

These recruiting efforts are paying off.

Rhegan McGregor, a fourth-year WWAMI student, joined the TRUST program because she saw the vital role doctors played in her rural hometown of St. Marie’s, Idaho, and wants to give back.

“What I really appreciate and love about rural health care is the relationships you can establish with your patients,” McGregor said. “As a doctor, you have to take on different roles because of the lack of resources. So you do more health navigation for these patients and try to figure out how to get them the care they need.”

McGregor, like other rural doctors, is in it for the long haul to the benefit of future Idaho patients.

“I love the full spectrum of health care, from the time you’re born to the time you pass away,” she said. “I love the fact that as a family practice doc, you can create those relationships and be there for the ups and downs. You get to go alongside patients for their journey throughout life.”