8 minute read

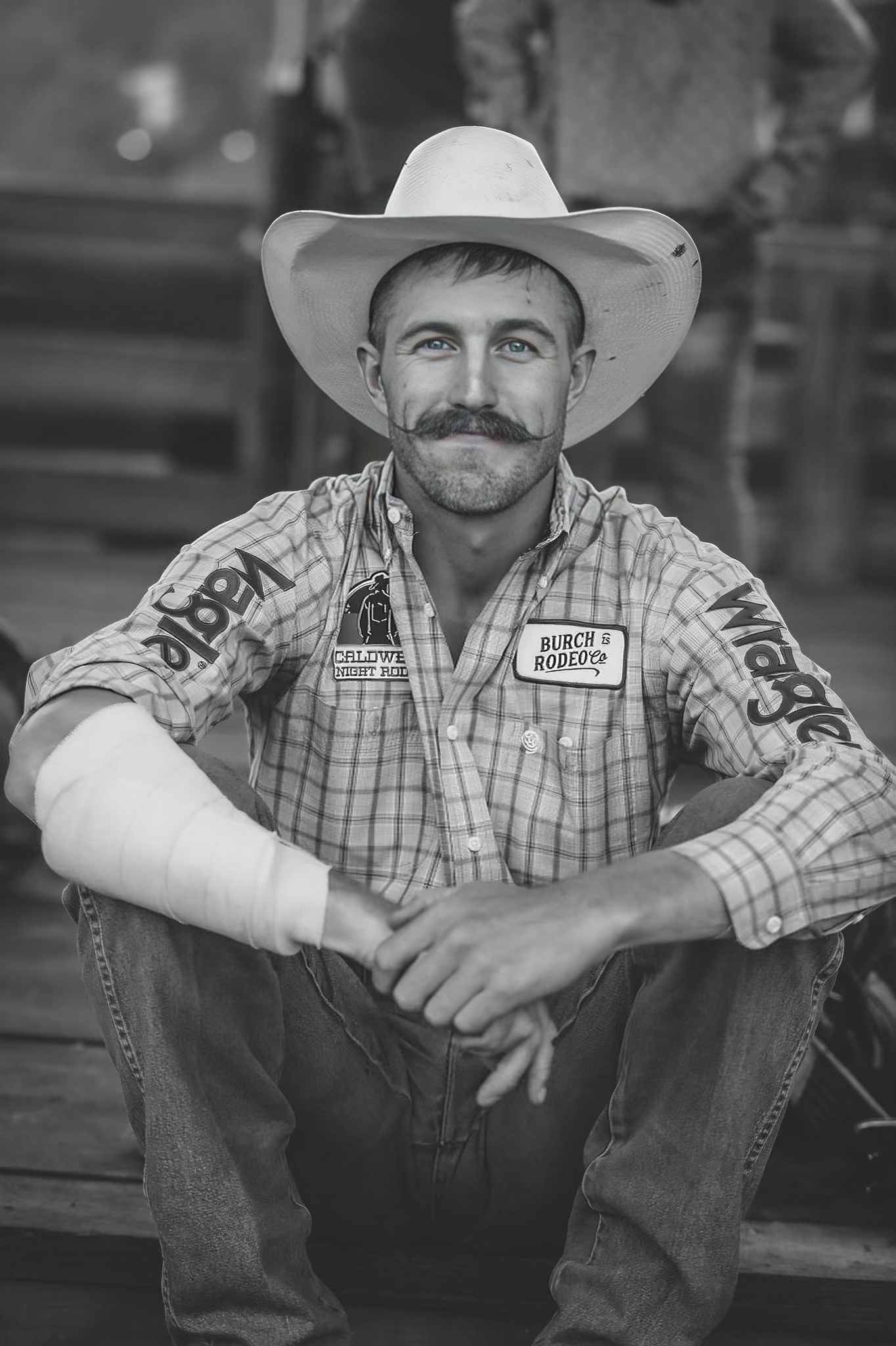

RAGS TO RICHES, BROKEN BONES AND STITCHES

Bull riders risk it all for love of the game

BY DREW DODSON

Sitting atop 1,800 pounds of pure muscle and pent-up rage, Brady Portenier nods, a gate swings open, and his mind suddenly runs blank. For the next eight-plus seconds—Portenier hopes—a battle of man versus beast ensues, and everything is on the line.

“To tell you the truth, bull riding’s the best way to clear a guy’s mind,” Portenier said. “Your brain kind of shuts off and you just start doing what it takes to get there.”

Portenier, a Caldwell native, is among an elite group of cowboys who earn a living riding bucking bulls in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. The organization sanctions rodeos all over the country, including the Snake River Stampede and the Caldwell Night Rodeo.

It’s late June, and Portenier is piled into a Sprinter van with fellow professional bull riders Roscoe Jarboe and Kase Hitt. The trio has been on the road for over a month now, driving from state to state, rodeo to rodeo, all in pursuit of another bite at the apple they so deeply crave.

“There’s nothing very comparable to bull riding as far as adrenaline,” Portenier said. “Not very many people in the world get to feel that feeling.”

That feeling has kept Portenier coming back to the tune of more than 800 bull rides since his career began in 2013, including some 300 rides that have gone the distance at eight seconds.

The sport of bull riding itself is simple. Cowboys must ride a bucking bull for eight seconds to earn a qualifying ride. Rides are scored on a 100-point scale by four judges who are former bull riders. Up to 50 points are awarded for both the cowboy’s style and control, as well as the bull’s ferocity. Scores in the 80s are good. Scores in the 90s are great. A perfect score has only been achieved once, by bull riding legend Wade Leslie in 1991.

Each ride begins the same for Portenier. He firmly grabs a rope handle tied around the bull’s torso and steadies himself on the bull in a tight, gated pen. Then, when he halfway doesn’t expect it himself, he nods for the gate to swing open. Before he knows it, he’s holding on for dear life as the beast beneath him violently thrashes, kicks, and spins.

There’s nothing very comparable to bull riding as far as adrenaline. Not very many people in the world get to feel that feeling.

“I kind of try and trick myself because it forces me to go into reaction mode instead of trying to anticipate what I’m doing next,” he said.

By year’s end, Portenier and his fellow traveling cowboys hope to ride bulls in at least 100 rodeos across the west. If they are lucky, their seasons won’t end until after a trip to Las Vegas on Dec. 5 for the National Rodeo Finals, an honor reserved for only the top 15 bull riders in the world. The only way to climb the rankings is to win rodeos and rack up as much prize money as possible, which means days off can be few and far between.

“If you don’t want to be on the road, being a rodeo cowboy might not be for you,” Portenier said. “Right now is the time where we’re really getting after it. We’ll have a rodeo every day for the next couple months.”

Portenier, Hitt, and Jarboe travel together to split the cost of fuel to get from rodeo to rodeo. Bunk beds installed in the van allow one cowboy to drive while the others catch up on sleep or study bull riding film between rodeos. It is neither an easy nor a particularly glamorous life, but that’s just fine by most rodeo cowboys.

“You’ve gotta love it,” said Hitt, an 18-year-old from Ardmore, Oklahoma, in his second season as a professional bull rider. “No one’s gonna do this unless you love it.”

Earning a living as a rodeo cowboy is a tricky proposition at best. Cowboys front travel expenses from rodeo to rodeo and are not guaranteed anything for their efforts. It’s either perform well enough to earn prize money, or don’t get paid.

A good season can net $70,000 or more. Earnings can swell north of $150,000 during a great season. But a losing streak and a few strokes of bad luck, on the other hand, and cowboys have only unpaid bills to show for their labors.

“You can’t be scared to bet on yourself in this game,” Hitt said. “I’ve spent my last dollar to get to a rodeo, pay my fees, and win the whole thing.”

A gamble, as it turns out, describes bull riding in every sense.

Mandatory safety equipment, like protective vests and helmets, have reduced bull riding accidents over the last 25 years, but it is still known as the most dangerous eight seconds in sports for a reason. Injuries remain common, and survival is not certain.

“It’s not a question of if you’re gonna get injured—it’s when and how bad,” Portenier said. “I think we’ve all accepted that long before we took rodeo serious.”

Last year, a lacerated spleen at the Lewiston Roundup derailed what had been a promising rookie season for Hitt, who finished ranked 38th in the world with just over $52,000 in earnings.

“The bull kinda shook me loose, and I come off on the left side and landed on my elbow,” Hitt recalled. “The tip of my elbow went in between my ribs and lacerated my spleen. I couldn’t catch my breath for about 20 minutes. It was just like someone punched me in the gut.”

Broken bones, concussions, and missing teeth round out Portenier’s list of bull riding injuries. He doesn’t relish the injuries, nor the scars he has picked up along the way, but he is quick to point out that they are part of the sport.

“The danger aspect is always gonna be there—it’s a bull ride,” Portenier said. “But that’s also what makes it fun.”

The danger aspect is always gonna be there—it’s a bull ride. But that’s also what makes it fun.

While aware of the danger inherent to riding bucking bulls, Portenier refuses to let it consume him. Like most cowboys, he is buoyed by a calm, fearless confidence. He is not cocky, nor boastful. He has a healthy respect for the bulls he makes his living riding.

The best cowboys in the world only ride the full eight seconds about 50% of the time. Yet, Portenier will strut into one rodeo after another with failure not so much as crossing his mind. His belief in himself is unflappable, as if he’s never known the feeling of being unceremoniously tossed from the back of a bucking bull.

“I pride myself on being that kind of guy, you know,” Portenier said. “I knew a lot of kids growing up that were just as capable, or maybe had more talent than myself, but I really take care of the mental side and I think that’s how I got here.”

Hitt has a similar confidence about him—not because he is young and brash, but because, like Portenier, he knows it’s as essential to the job as cowboy boots and chaps.

“As soon as I put my helmet on, I feel like I’m going to war,” he said. “It’s only me and the bull, and only one of us can come out on top, and it’s going to be me.”

That brand of unrelenting, almost foolish confidence is not just part of the act for professional bull riders like Hitt and Portenier. It’s their way of life.

Each time bucked off a bull, they say, is just another chance to get better, another chance to prove themselves, and a microcosm of one of life’s broadest lessons.

“That’s what’s cool about being a bull rider—you test yourself daily, and you realize you can do things that maybe you didn’t think you were capable of before,” Portenier said. “We’re just very lucky and blessed to get to play the game.”