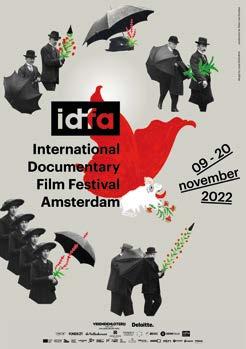

International Documentary Film Festival

Artists and filmmakers are doing a lot—they are trying, reimagining film language, rethinking the art of the documentary, putting forward new proposals, “succeeding” and “failing”, losing sleep, digging up their own bodies, memories, histories. All in their quest for that moment which brings the many together, for that precious and rare magic of cinema that connects people across cultures and beyond barriers. That widens our senses and broadens our horizons. As they seek that magic, many filmmakers put themselves out there, naked, to be watched and easily criticized.

It is the curse of a filmmaker to spend years working on a final film that we get to watch and must judge in a short moment of time. A filmmaker making a documentary film with artistic ambition works full-time for an average of four years. If we ignore the unignorable sleepless nights and the weekends they must put in, we can say that a film takes about 10,000 hours of one (or more) director’s life, in addition to variable fractions of that from the lives of many others too. Then, we have the privilege of judging it right after watching its final duration—mostly in less than two hours. Furthermore, filmmakers get paid poorly, and have low safety levels, with regards to their health, their bodies, and their finances. This makes the filmmakers the working class of the film world, with less than one percent of them breaking through to the top of such a hierarchy, according to the terms of reference of the trade.

The history of film, and of arts and culture in general, has often revolved around, and been defined by, hierarchy. Who is the boss? In no uncertain terms, the system we work within deems the one with money (or the one whom money follows) boss. Yet how can we, the documentary community, accept such a system? It’s an unfair, abusive system of “gatekeeping” that sees filmmakers and their works as a bulk of people queueing towards the source of power. And it’s a betrayal to what we purport to stand for.

Our collective well-being, as much as our usefulness to the world, requires that we outgrow the financiallyfocused evaluation system of a film’s value. It requires

that we find a more collaborative way of working as a community; a new system that recognizes and fosters a partnership between the artist and those who support and enable them, promote them, and “judge” their work. Such a partnership requires mutual respect and a profound acceptance of the openness, the riskiness, and the singularity of the creative process of each true artist. Such a partnership requires engaging the filmmakers— rather than othering them—with the debates and questions around film, the film industry, film festivals, criticism, ethics, and film studies.

Then, on the other hand, such a partnership requires that we—non-filmmaker film professionals—openly and respectfully share our challenges, questions, and our very thought process with the filmmakers themselves. The old walls separating groups of film professionals are resulting in this huge difference in language, in vocabulary, and in a highly commercialized documentary film environment.

Together with our annual book recommendation and various year-round online publications, Notes on a festival—this new publication in your hands—is a small first step towards acknowledging the distances between us. We would like to invite our community to spend more time contemplating the work we do, all the filmmakers’ efforts behind it, and the wider meaning documentary film tries to add to our lives. So that all our different angles, understandings, debates, and even our language itself, can gradually come closer to each other as we think and work in film. This is to advocate for a film world that is a safer place for its own dissidents, and to imagine “film culture” as a common pluralistic ground, as a forum of thoughts and experiences in continuous conversation, that is not ruled by powerful men or institutions.

Orwa Nyrabia Artistic Director

NOT YET YES

Simon(e) van Saarloos

Tue Steen Müller

IN THE ARENA Alexander Nanau THE BIRTH OF A MARKETPLACE Nilotpal Majumdar GO TELL IT ON THE MOUNTAIN Amit Madheshiya and Shirley Abraham SENSING AND SENSE-MAKING IN OUR NERVOUS SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION William Uricchio INTERVIEWS Julia Yudelman FOR THE ARCHIVES Films, new media,

What does queerness without a closet look like?

A queerness that defies the existing structures, a queerness that refuses to come out, because you will simply land in a society seeped with encapsulating normativity? Queerness without a closet questions not just the structure of the closet—the shape, the size, the individualizing enclosure, the material with which it is made. Queerness without a closet especially considers the space outside—where a narrow formulation of freedom appears as the ultimate happy life. Queerness without a closet will tell you there is no inside or outside. Queerness without a closet stirs from an embodied understanding of constant displacement. Harnessing the recognition that any place that offers the experience of a shielded inside, a space to gather—forget about rest; a quiet bed is too much to ask for—will be demolished,

refurbished, revitalized, sold on the market. Queerness squats. Queerness practices a position between running and resting.1 Queerness without a closet formulates a love language for walls that do not hold.2

Often, queerness is presented as a cut. A disruption of a line. A stepping out of the box. A tradition broken. A family falling apart. But queerness might just as much be an insertion. Added time. A slowing down that allows for the insertion of many different voices.3 A sonic cacophony without space widening or stages opening up. A conversation without seats and a table. A refusal to leave the land. A barricade—a body in the picket line or a fist raised from bed⁴—that makes capitalist comfort impossible.

For IDFA, I want a Queer Day without closets. Confined by the structure of a pre-announced day, the separability of a noted date, I define this attempt as Not Yet Yes. This Queer Day is not yet a yes, it is not yet a success. It drifts in failure, incompleteness, a liminal stretch for touch and slow transition.⁵ More concretely, the films shown on this day will not end with a yes. Refusing the yes opposes the trend of many documentaries that are cataloged as LGBT or even queer, in which the protagonist moves towards an increased level of comfort. This comfort is likely conflated with “more out”, more proud. Often, this stage of development marks a break with the main character’s home country and freedom is therefore portrayed as a promise behind the walls of Fortress Europe. So often, LGBT documentaries convey a racist humanism that enforces a globalized conception of freedom. This hierarchical thinking portrays freedom as already reached in the most developed nations. It projects a freedom everyone wishes to possess and therefore excuses violence as a means of protection.

And it is not just LGBT films. Even if there are zero gays on screen, even if heterosexuality flaunts as the

normative background of everyone who appears in the film, most documentaries follow the format of a coming out, because the description of the closet is portrayed as the first step towards freedom. People suffer, we see, we learn. Even if the people portrayed do not get to “come out” of their oppressive reality during the film itself, a promise of progress lingers, as we—an audience watching—are witnessing.

As viewers, we witness suffering and oppression with a feeling of future potential: us watching, means us learning. Us learning, means us knowing. Us knowing will mean change.⁶ The moral force that drives and funds a documentary film festival is a belief in visibility: if we see, we know. If we know, change can happen. Sadly, this inseparability of knowledge and progress is a colonial project.

Gnosis Iluminada by Agustín Ortiz Herrera (2022). Photo by Daniel Cao. Presented as part of the Not Yet Yes programSadly, this inseparability of knowledge and progress is a colonial project.

Documentaries visualize. “Visualizing,” Nicholas Mirzoeff writes, “is the production of visuality, meaning the making of the processes of ‘history’ perceptible to authority.”⁷ Documentaries do not just portray violence, they reinforce violence. They affirm the most privileged of people in their guilt-ridden feeling that it is their obligation to look at injustice. As if the looking itself is a first step towards taking action against oppression, instead of understanding the act of looking itself as an oppressive grammar. Why are documentaries not flagged as a surveillance technology? The portrayal of real life mostly reproduces how we understand and categorize “real” and “life” and what deserves to exist and preserve livelihood; it cannot aid us in thinking differently about the meaning of “real” and “life” altogether.

Fiction is dependent on material conditions that are currently utopian. Yes can be imagined when fiction does not need to prove its value by serving a large audience. Yes can be imagined when fiction is free from the ambition to aid our intellectual development and so-called civilization. Yes can be imagined when fiction refuses the outreach of empathy. Yes can be

imagined when fiction dares to call itself documentary and documentary dares to call itself fiction. Yes can be imagined when fiction does not produce relatable stories. Yes can be imagined when fiction is no longer viewed as a genre—not for marketing purposes nor as a marker of discipline and skill. Yes can be imagined when fiction refuses the democratic ideal that a story becomes a story when it is understood by many.

Yes can be imagined when fiction does not collect and capture what is already possible, but dreams the impossible present. When fiction formulates a politics that does not yet exist. Not by visualizing it, but by inserting the loud absence of impossibility. While fiction

Yes can be imagined when fiction dares to call itself documentary and documentary dares to call itself fiction.

requires a willing suspension of disbelief, it does not ask for a yes or for all noses to point in the same direction (to use a Dutch expression).

Not Yet Yes does not signify the absence of yes. Instead, it opens up the potential of an abundance of yesses, as it delays and procrastinates the yes. It projects satisfaction beyond the first encounter with a yes. It imagines so many yesses, that the first possible yes, the first possible agreement, the first encounter with freedom, the first big experience, the first lover, job, pronoun, sex, gender expression, body, kiss, acknowledgement, welcome, arrival, passport, delicious dinner, antiracist dream becomes only one of many. Not Yet Yes signals the political refusal to be satisfied with less.⁸ Not Yet Yes defies police defunding, and desires abolition, and then the abolition of the need for abolition. Not Yet Yes refuses party politics and the democratic majority. Not Yet Yes claims that a yes just to stimulate agreement is always a yes too soon. Yes we can! expressed a premature acceptance: We have not even dreamt all possible meanings of yes and the implied “we” is the wrong we to say yes to.

Not Yet Yes signals that we do not know and cannot know and refuse to know (the value of) consent. In this current world order, how can we trust a yes as enthusiastic consent? How can enthusiastic consent exist, if we have not even practiced multi-layered freedoms to be enthusiastic for? The consent rituals that queers and feminists formulate today are helpful tools for interpersonal survival. But to say we know what yes means, to say we understand consent, is a way too monogamous commitment to the current order of things.

In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel R. Delany describes his intimate experiences of the movie theaters on Times Square before gentrification and tourism devoured this part of New York City. It’s the late eighties, early nineties. Delany goes to the movies a lot, and, just like many other men, sits down or scavenges around, seeking sex with strangers and familiar faces. Sometimes the men are homeless. Sometimes the men are professors like him. Sometimes the men have nicknames, such as the Mad Masturbator. Sometimes the men do not want to be touched. Often, they do.

Sometimes the men do not identify as gay. Sometimes they refer to their girlfriend at home or their mother in the hospital. Delany describes what is happening in, on, and between the seats inside the theater, but he also focuses on what is happening outside, on the streets. Shops are closing, sex workers are getting arrested, rents are going up, bars are forced to close down. Policing increases. Before the theaters are pushed out of the city completely and public sex is fully criminalized in the late eighties, the theaters function not only as cruising grounds, but also as a warm hide-out for those who sleep outside. Men chatter and suck dick. The films on screen often show heterosexual porn scenes—Delany observes that the first films were plot-driven, later less so. “There were some wonderfully wacky women,” Delany writes, while he considers the guys “absolutely without sex appeal.”⁹

instead of participate in what’s going on—they exit the theater and Ana expresses her surprise:

“It was so easygoing. And you didn’t tell me…” She paused. “Didn’t tell you what?” “—that so many people say ‘no.’ And that everyone pretty much goes along with it.”

“I guess,” I said, “when so many people say ‘yes,’ the ‘nos’ don’t seem so important.”

“Well, there’re still more ‘nos’ than ‘yesses.’”10

The inevitable presence of nos seems to be the prerequisite for having a ton of yesses. Not Yet Yes echoes this: An abundance of yes is unimaginable most of the time, because we do not live in sexy cinemas. We live in a society in which those spaces are eradicated and criminalized. We live in a society where saying no is penalized, sick days are sparse, police orders cannot be ignored, non-reproductive acts are meaningless. Not Yet Yes signals the need for an unapologetic and illegible presence of nos. Nos do not have to be loud and clear, in order to be understood. The deep potential of the no—a no meaning something more than a rejective response to violence and force—needs a space to exist and be explored before dreaming of unimaginable yesses becomes possible.

Delany’s account teaches me why I’m interested in film. Not because of what is being shown, but where film is being shown, and how. I believe in cinema not as stories on a screen, but cinemas as actual spaces. Those whom are seeking to spend pleasurable and unproductive hours in the dark have become narrators of displacement, gentrification, and exclusion. My desire for film shows up in the need for spaces where DIY-organization and mutual exchange can happen, where whispers in the dark count as a conversation, where amplification is not necessary, where you can choose a different name each time—if you introduce yourself at all. The films that are shown on the screens in Delany’s essays are important, but not because of the stories and the characters that appear. The films are an excuse, demanding a place to gather. The audience is facing the screen (if not bent over someone’s lap), but not because they need to recognize what is portrayed as their own, nor because they need to agree with what is shown. The encounter happens elsewhere. Relationships are not created through the identitary reach of the storyline, or the director’s attempt to evoke empathy. Impact is not controlled or reproduceable, even if the same film is screened on repeat.

When Delany’s friend Ana asks if she can join, he invites her along. After some adventures—Ana is approached several times, and in response, she asks if she can watch

Coming out further highlights the entitled existence of the closet. Reveals do not lead to change. Visualizing injustice just reproduces the authority of those who have the power to visualize. Only when we have actual spaces and material places where it is safe to say yes yes yes in multiple and incalculable ways, can visibility mean something more than exposure to authority. For queerness without a closet to exist in film, capitalism has to be overthrown.

For queer documentaries to exist, the policing of plush has to seize. In movie theaters, the “welcoming” opening videos that show you the “do not disturb” rules have to go. No more silencing, shushes, or expensive prized tickets. Not Yet Yes signals: We have not yet witnessed queer cinema. We have barely experienced and imagined the material conditions that make queer film possible.

I believe in cinema not as stories on a screen, but cinemas as actual spaces.

1 A position between running and resting does not have to look a certain way. A queerness that squats is not necessarily ableist. It does not live without tools and aids that help us move. Disabled queerness lives with the fugitivity of tools and aids and networks of care—all of which are constantly displaced, taken away, suddenly no longer covered by insurance. A queerness between running and resting, hinges on George Jackson and his letters written from prison: “I may run, but all the while that I am, I’ll be looking for a stick.” Michelle Koerner. “Line of Escape: Gilles Deleuze’s Encounter with George Jackson.” Genre 1 June 2011; 44 (2): 157–180, 160.

2 “walls that do not hold” nods to the film Adamu Chan made: What These Walls Won’t Hold. Chan started making films while incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, California. Once released, he continued to work with people inside and outside to get his friends out. What These Walls Won’t Hold focuses on the intimacy and love that is shared between people, exceeding the prison walls. While the abolition of prisons is needed to liberate us all, Chan shows that, amidst state violence, strong relationships are built.

3 Slowing down cannot be equated with “crip time,” but the call to slow down does relate to crip understandings of time. Crip time teaches us not only that some things might take longer or shorter amounts of time than what is normatively prescribed—crip time refers to the ways in which certain speeds and times are assigned to certain behavior (lifting your arm takes a second or two, getting out of bed takes you however many minutes, learning to speak or read takes a child about this many years, we should date for this long before marrying) and disrupts these norms. Most often, crip time is seen as a call to slow down, because disability is portrayed as a hindrance that unsettles the efficient rhythms of a productive life. In Feminist, Queer, Crip, Alison Kafer proposes that crip time can indeed mean “extra” time, or slowing down, but it should more so be regarded as “a reorientation to time”; an appreciation of different velocities and temporalities and an acknowledgment of the many ways bodyminds move (27). Kafer suggests that “rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.” (27) Simon(e) van Saarloos, Against Ageism. A Queer Manifesto (Emily Carr University Press, 2022).

The insertion of many voices might refer to Claudia Rankine and John Lucas’ film Situation 1, in which Zinédine Zidane was assaulted with racial slurs. Zidane, playing his last soccer match before retirement, responded with a headbutt. The few seconds that were played and repeated all over the world, are stretched into minutes by Rankine and Lucas. A daunting heartbeat underlies Rankine’s voice, citing the writing of James Baldwin, Homi Bhabha, Frederick Douglas, Franz Fanon, William Shakespeare, Richard Wright, and Zidane’s own words.

⁴ “the fist raised from bed” cites Johanna Hedva’s text Sick Woman Theory: https://johannahedva.com/SickWomanTheory_Hedva_2020.pdf

⁵ Slow Transitions is a workshop developed by performer Nattan Dobkin. Dobkin wondered whether between the binary male and female, there is more to add than “non-binary” alone. Instead of having another identity category to signal a kind of beyond and in-between, a slow transition might not ever reach one end of a binary, nor choose a middle ground. The workshop Slow Transitions “investigates the temporality of slowness as a method for change. The gathering will explore ‘mythical’

linear movements and how they can become radical when done in slow motion, such as with gender transitions, aging and even the process of committing to a relationship.” To learn more about Dobkin’s work, listen to the Worlding Podcast, “Episode 7.3, Detours and Slow Transitions,” May 4, 2022.

⁶ In Take ‘Em Down, I cite Cathy Cohen and Eve Sedgwick and ask: Does “knowing” help to perpetuate “never again”? Not if we follow political scientist Cathy Cohen in her analysis of racism after the US elections in 2016: White people too have known for a long time what’s going on; there is sufficient proof and there are countless examples to be found. Knowledge does not make people less racist, but ignorance is nevertheless deployed as a strategy for exercising power, Cohen observes. Sedgwick too writes about the power of ignorance. Ignorance is deployed to determine the level and tone of a conversation, to make people explain endlessly what it is that they mean, to make them continually repeat the same thing. Ignorance demands to be met. Sedgwick, like Cohen, is not convinced that additional knowledge makes an effective contribution to combatting inequality. In her essay collection Touching Feeling, she describes a discussion with a friend. Sedgwick is incensed by the possibility that the US Army was involved in the spread of HIV. She demands someone investigate what really happened. Her friend reacts with skepticism to Sedgwick’s indignation. Would it really make any difference if proof was found? She concludes it would not. So many scandals have already been proven factually, and those abuses were not resolved or fundamentally changed. If people only knew, they would do something—that hopeful thought is dangerously naive, Sedgwick concludes. It’s paranoid to think that an underlying, real truth would change everything. We have known for a long time. We don’t need a deeper, more real, and confronting truth to prompt us to act. The fact that we’ve done nothing is more true than the possibility of revealing the truest truth. People know and do nothing. Knowing and remembering do not impart morality. Simon(e) van Saarloos, Take ‘Em Down. Scattered Monumements and Queer Forgetting (Guelph: Publication Studio, 2022), 65-67.

⁷ Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2011), 3.

⁸

“Not Yet Yes” echoes José Esteban Muñoz’s formulation of queer as “not yet here”. In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, Muñoz writes: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer.” José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2019), 1.

⁹

Samuel R. Delany. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 77.

10 Samuel R. Delany. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 30.

From the beginning, the market was conceived as an agora for our industry: a place to meet, exchange ideas, and discuss. The goal was to foster a fruitful climate for collaboration and co-creation. But that model was never beyond critique.

There was the danger of ‘Europudding’ as we heard in the ‘90s, but many producers and directors actually embraced this collaborative model—whether out of necessity or creative benefit. Gradually, we found that collaboration and co-creation, while essential in documentary filmmaking, can also lead to power imbalances.

Over the years, we saw the importance of narrative ownership and films that explore untraditional ways of storytelling. That also meant challenging traditions in themselves, as IDFA Forum sought to find answers to current points of congestion, different avenues for financing, and new formats for production.

Three decades later, we present three different stories of the Forum, told from three different perspectives. Because what’s the point of celebrating if you can’t share the cake?

What’s the point of celebrating if you can’t share the cake?IDFA catalogue cover from 1993, the first year of the Forum. Design by Jan Bons.

Memories… Names, film projects, episodes. 30 years of IDFA Forum! Actually, I don’t remember the first time I attended the Forum. Was it the first edition? At the time, I worked at the National Film Board of Denmark and had a seat in the Board of the EU office. I remember that Dane Thomas Stenderup, representing the EU documentary office based in Copenhagen, traveled to Amsterdam a lot to meet with Ally Derks, Adriek van Nieuwenhuijzen, and other team members to talk about how to set up what has now become the most important documentary meeting place in the world. Documentary filmmakers of the world unite.

An event that many came to love and many came to hate. Many asked: Is there really money just for the taking? Is it a financial market? A meeting place? Many thought: What even is pitching? It is absurd to think you can present your film idea in seven minutes—especially when you have been working on it for years! But it turned out that the pitching was followed by conversations, discussions, networking. It became obvious that if you had made yourself visible, inspired, and engaged, a lot of work waited for you.

I have talked with many veteran documentary filmmakers who remember their first time pitching as a scary one—a kind of exam. At the same time, it was a good place to start gaining the knowledge they needed to build their international careers. I have heard again and again, even among the skeptical, comments like: “You have to go to the Forum every year.” “You have to show your face otherwise people will think that you are no longer in the business!” It became the meeting point and, being sentimental, I sat there as an observer for the plenary pitch session thinking: “Wow, all these people are involved with documentary films! What a show of solidarity!”

A few words about the projects: I was part of the selection team for IDFA Forum projects several times when EDN (European Documentary Network) existed as a partner for the Forum. It was always great fun, and a challenge, to find a balance between the more creative films and those clearly targeted towards television. You knew to expect strong journalistic BBC documentaries in the run for a pitch seat and that they would get it, whereas a personal poetic documentary from Serbia would have difficulties getting a place at the table. Fair enough for commercial thinking, but at this point, it must be stressed that Adriek

and the Forum team have been great in their continuous, flexible search for changing the original model—shifting from one huge plenary session to smaller group meetings to go deeper with each project. Here is a quote from 2019: “…the Forum is adjusting to changing financing structures, while opening up to also include films with less clearcut narratives and new ways of storytelling.”¹ Meaning less boring formatted projects, more surprises, more experiments—that’s how I see it.

The editors and pitchers: The Forum must also be entertaining—from both sides of the table, we observers sit there expecting some show elements. During Viktor Kossakovsky’s pitch, you had someone who knew how to catch attention with a globus for !Vivan las Antipodas! There have been people “dancing” their project. And honestly, I miss the at times tough dialogues between Arte’s Thierry Garrel and BBC Storyville’s Nick Fraser. Representing the auteur tradition and the investigative journalistic/historical. Later on, Iikka Vehkalahti from YLE joined the table with competent and humorous support, when appropriate, for the artistic documentary. Not to forget wonderful Diane Weyermann—always pleasant to listen to. RIP. Who has taken over from these docu-stars? Far too often you hear: “Thank you for the pitch” or “We have a meeting later today!” Boring and incompetent.

As I write this (August 2022), I am sitting at the MakeDox festival in Skopje and there is a Forum taking place for Southeast Europe. In the beginning of September, there is the Baltic Sea Docs, and later the same month there is the Nordisk Panorama… and so on and so forth. These are many regional alternatives to the Forum, and many represent first steps for filmmakers before being selected in Amsterdam.

The IDFA Forum of today: It’s the full package. You arrive. You can be trained for pitching. You can have your trailer checked and improved. You can find all kinds of information on the market. You are invited to sessions and receptions to meet colleagues and funders. The only thing the Forum does not deliver is this: You don’t learn how to make films… but it can give tools and inspiration.

1 “IDFA Forum goes tailor-made, expands cross-media market for 2019,” IDFA, published April 30, 2019, https://www.idfa.nl/en/article/115123/idfaforum-goes-tailor-made-expands-cross-media-market-for-2019

Both times I pitched at IDFA Forum—quite a while ago now—I was invited to pitch in the frightening but rewarding arena of the central pitch. When I was first invited to pitch, the Forum team had decided to start favoring trailers and their visual quality as the main selection criteria, over the written treatments of the submissions. Since the projects I pitched, Toto and His Sisters and Collective tended to sound more like totally exaggerated and pretentious narratives on paper, born by a kitschy mind, I have always preferred to let industry trailers do the talking. I had learned how to edit pitching trailers, that could already show the film’s themes and the chosen character’s potential, at the Documentary Campus development program. Editing trailers, from footage shot during research, informed the developing process of my projects from there on.

I would find a theme, invest in it for proper preliminary shooting with the chosen characters, sometimes up to three months, and return to the editing room for at least another two or three months. Through editing, I

would experiment and test the story idea—the world I entered—to explore whether I managed to capture the authenticity of the people I decided to follow on camera, and to search for the right cinematic, visual language to transport it all.

Only when I would get to a point where a trailer of four to five minutes would convince first of all myself on all the needed layers, would I be ready to fully jump into the risk of spending a couple of years on the project. The trailer would now have to convince other people to share the risk with me, and to let me spend their money to make the film.

Even if always very frightening, pitching in the Forum arena was for me, first and foremost, a crucial testing ground for a future film. A space to test a local Romanian story in front of an international audience.

Convincing, in a run against time, two dozen or so commissioning editors that are ready to dissect your

proposal, in order to see if it stands its ground, serves their professional agenda, and also fits their personal tastes, can be quite something during a fragile stage.

Nevertheless, for me the advantage of the central pitch was the additional 300 industry professionals watching from around the pitching stage. 300 people ready and willing to be inspired by the pitching teams and their projects from around the world. It was not necessarily easier with so many eyeballs on you, except for that once the pitch was on and the trailer was playing, such a high number of people in one room ceased to be singular professionals and melted into what we call an audience. During the four minutes when the trailer was playing, one could sit back on stage, and observe and feel the room reacting (or not) to your material, characters, and story.

I have also always highly enjoyed watching the Forum central pitches as an audience member. One was curious about the next project; about the stories the filmmakers had found around the world and about the visual approach they had chosen to tell the story. There was a different approach in almost every pitch— excluding those already formatted for a certain strand or commissioning editor—and documentaries still felt like the most creative film form out there.

During good pitches with strong trailers, one could feel the room light up and the crowd being sucked in. The audience had a collective experience. During these moments, when a cinematic vision of a story and characters from somewhere around the world had met and moved the Forum audience, one could feel the birth of a great future film in the room.

During good pitches with strong trailers, one could feel the room light up and the crowd being sucked in.

Marketplace: The very word evokes something opposed to the profuse self-esteem of an artist. For many of us from South Asia, it remains staunchly as a bazaar—a utility lifeline of shameful profit, a business of marvels run on a disruptive cash flow, and a pleasure-seeking population. An energy that goes against anything holy the art school implanted in us.

Nevertheless, despite the suspicion from the enlightened liberals, the marvelous market of bliss was born. It was true that a few untamed radicals pledged to make it an art.

Ancient markets had always been places of exchange, and of being recognized and acknowledged for creativity. Everything from artworks, like baskets and axes, to other crafts were ecstatically offered to entice inspired, non-craft buyers. The material transaction was joyful, innocent, and emotionally defensible.

We, in this subcontinent, heard about IDFA Forum, a magical place to help stories thrive in collaboration

with others. There, a storyteller could be heard with immense curiosity for chiseling out a simple truth, or for bringing us a surprising experience of reality. A group of alternative thinkers could participate with creative and financial investment, taking stories back home for their own citizens. With this freedom, the magic of the real could be resurrected in an open market of ideas. The act of co-producing knowledge could be shared graciously and responsibly.

We began to wonder, would it be possible to unveil a similar platform for our filmmakers? Could we have a marketplace of our own in India? The idea felt fanciful, absurd, and untenable in a black-hole ecosystem of virtually no television slots, producers, professional training, or audiences.

But we did have one thing: A strong group of fiercely independent filmmakers and growing talents developing their own language. At the very least, we could bring people who matter to our doorstep, to originate a dialogue with those filmmakers.

We adapted a micro IDFA Forum model with European Documentary Network (EDN) creative support, dreaming of a kind of native marketplace emerging in India. Without any local investors for filmmakers, with limited knowledge, and with a great degree of anxiety, we commenced a much smaller, experimental version where filmmakers had opportunities to share ideas with and reach out to professionals. The seeds of DocedgeKolkata were planted.

Things started happening slowly but firmly—a small group of filmmakers and a tiny bench of commissioners! Within a couple of years, with other institutional support, European and Asia Pacific broadcasters’ funds and a few foundation grants became available for supporting some intriguing projects.

style, as opposed to the taste and preoccupations of commissioners, that would determine the future of the commune of homegrown stories.

The first Docedge-incubated project that pitched at IDFA Forum was Journals of a Wily School, directed by debutant Sudeshna Bose and produced by Debu Bhattacharya in 2006. It was a path-breaking international co-production with grants, broadcasters, and co-producers from Europe and North America. In 2017, with big applause, Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas presented Writing with Fire with Margje de Koning of EO/IKON and Tabitha Jackson of Sundance Documentary Fund on the table as partners and John Webster as a Finnish co-producer.

After a few years, however, it became necessary to reflect on whether we were sincerely looking for a buoyant market, or an intimate commune to explore visual language and form, and make an attempt to find artistic solutions for presented projects. Money on pipelines was limited, and choices were mandated. There was a serious need for nuanced training and skill enhancement for filmmakers to make others view the world through their own lense.

Strange and powerfully artistic content would be what inspired and provoked the collaborators. It would be the filmmakers’ artistic acumen and storytelling

Over the last seven years, we kept on revising the mentoring model and focused on finding the community inspired by the language, forms, and delight of cinematic storytelling. We expanded our program, further adding masterclasses, curated film screenings, and special sessions on other creative specializations like camera, editing, etc. so that participants get layered insight into the craft of storytelling from every session. DocedgeKolkata was transformed as a platform from how to pitch to how one best develops the idea and finds appropriate creative tools for expressive storytelling. This is not to undermine the market, but to elevate it as an irresistible place where you breathe in stories deeply, contemplate, and eventually get involved!

With this, we find DocedgeKolkata, Asian Forum for Documentary, as what it is today. Even with relatively less money on the table, and the unresolved view on ‘South Asia’ as an enigma for investors, it is, perhaps, the most ambitious space for filmmakers in the Asian region to launch their projects to an international community. Creative documentaries from South Asia are becoming critically acclaimed globally, evoking cross-cultural discourse with great festival runs, thanks to our native marketplace.

A marketplace of our very own.

With this freedom, the magic of the real could be resurrected in an open market of ideas.Journals of a Wily School by Sudeshna Bose (2008).

It’s no secret that the current state of the world has put artists under threat—whether by war or the violence of state censorship. But there’s also the so-called creative industry to contend with: an overload of images, a streaming landscape saturated with bite-size content, a volatility in financing structures as old models make way for new. All that boils down to a rapidly vanishing space for the artistic process of documentary filmmaking.

At IDFA, we’ve responded by continuously trying to shore up that space. 25 years ago, we started an international fund for filmmakers. Formerly known as the Jan Vrijman Fund, the IDFA Bertha Fund was soon joined by a slate of talent development programs, and eventually, a whole department for supporting filmmakers—all of it an attempt to protect a space for artists, especially newcomers and those with less opportunities, to explore their own creativity.

At the same time, it’s a tough balancing act. How can filmmakers explore the documentary art form, find their place within the industry, and push the boundaries of the market? Reflection, we think, is the key to making sure the scales don’t tip. And who better to ignite some reflection than a couple of filmmakers?

“Why do you want to make this film?” asks a commissioning editor. “The story has grown roots in me, it bids me,” I respond, trading precious pitching time for a little Rilke1. It has been four years of loneliness with this film—my first one. The film tells the story of three outliers who are striving to keep one of the last traveling cinemas in the world going. This story now torments me to be let out. “Do you know which film you should be making instead?” asks the editor. Promising me quick deliverance from my struggles, she suggests a David versus Goliath story. A time-tested formula, that

can be quickly made, instantly distributed, and can rain money on me. I could even be famous, having made “an important film,” she says. I feel I am not ready to smother the one story that sits in my soul and stirs it.

Overwhelmed and defeated by the market, I retreat. I do not know the path ahead and make an escape to the story inside of me. That is the one true thing I know. Like the truest sentence Hemingway inspires us to write, in moments of doubt. I must be naive. Now I’m writing brochures for chemical companies

20

and funneling my savings into the film. This drip-feed of resources cannot sustain it and the story begins to wither away. Concerned that I will never be able to finish the film, I start working late nights, also on weekends, and think that the joylessness of it all is lofty. I become my own assistant. Rather, multiple assistants all chasing chimeras to light one film. Writing theses while applying for film grants. Typing dozens of emails every day to potential funders. I am mostly waiting for a leaf to flutter, somewhere.

a giant unknown—it’s just that phrasing it like Werner Herzog helps me to not laugh at myself. I think of that commissioning editor’s offer with a tinge of regret. The only solace that I can find in this enterprise is born out of my own hubris: I am making an independent film.

Despite the hardships, I now love being on this mountain. Master of my own destiny, as I would like to believe. Here I find myself independent of the structures that the world has raised and the glittering currencies it transacts in. Mercifully, I don’t have a hierarchical superstructure to aspire to and there is no one to fuss about insurance and equity options. I feel like a grateful outsider to the most common structures of capitalism. I have become a fugitive.

But my fugitiveness is neither approved nor appreciated by my family, society, and government, all of whom want me to conform. While they dismiss my work, they also seek to crush it—so that I become a body that can be easily loved and governed. I am a difficult citizen of both, just for seeking my freedom.

As time stretches on this film, its agony becomes non-linear. It now dawns upon me that this is perhaps the most arduous and circuitous path to make a film. Also, a foolish one. It feels like I am climbing a mountain alone, with all the gear on my shoulders. The heavier, and greater, burden is that of looking for

I am not claiming an all-encompassing sovereignty. My fugitiveness is the foundation on which I build my practice. It is an attempt to claim freedom. Even if it comes in tiny, somewhat unfulfilling slivers. Sometimes the freedom is in owing my time. Sometimes in stealing solitude. Sometimes in the blind devotion that I wish to infuse my work with.

The only solace that I can find in this enterprise is born out of my own hubris: I am making an independent film.

Sometimes the freedom is in nurturing wayward stories by letting them grow roots in me. Largely, I want the freedom to walk towards the unknown. Unfettered by the shackles of convention, money, and my mortality. I might consider it a heroic overture.

not telling the story of technological obsolescence, or a mere elegy to celluloid, but a paean to the human imagination—to the wonder of cinema that is timeless and thriving. It continues to be a primeval experience, writes Angela Carter, like “ancient Greeks participating in the mysteries, gathering together in the dark, to dream the same dream.”2

Claiming freedom in slivers, I finish my film on the traveling cinemas. Eight years. The Cinema Travellers, a film that I discovered in my fugitiveness. My place for contemplation and creation. Here, as the world recedes away from my consciousness, I begin to tend to my material. It is a meditative process, guiding me to look within. To the source of nourishment for the roots of the story. My job is to air the soil, sprinkle some manure, and keep watch.

In time, the story blooms. It is a symbiotic process, catalyzed by an amalgam of time and solitude. The blossoms are as much of the story as of a new me. New life brings a new way of seeing. I learn that I am

In fugitiveness, I learn that the pursuit of non-fiction cinema finds resonance with the metaphysical question that Plato posed: “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?”3 Non-fiction cinema is an ephemeral art. The more I try to perfect it, the more reductive it becomes. It reveals to me the grace of imperfection. It teaches me to embrace uncertainty and not-knowing as the only certainties of this craft. And in its transience, my artist’s self subsumes. My vanity melts. Pursuing it with such detachment makes it a humbling experience. A duality of existence—of completely surrendering to what I know and an absolute commitment to where the not-knowing will lead me.

Even in my state of delirious epiphany, my family and society don’t tire of pointing to the deliverance of the Deus ex machina, hanging right above my haughtiness. I only have to descend from the mountain and the

Non-fiction cinema is an ephemeral art.

creative industry will cradle me with open arms. I received many offers in the booming documentary market—they were weighed in gold. And corroded by two words: “content” and “reality”, that are merrily hollowing out non-fiction cinema. “Content” is that smug word in contemporary culture that has come to exemplify anything that can fill someone’s time. It can be directionless, formless, craft-less, even banal, but is worthy of shoveling money in if it can colonize people’s time. Grab the eye balls, as they say. Don’t let them fall asleep.

“Reality” through mainstream offerings is a loosely orchestrated piece involving “real” people in supposed “real life” situations. Usually engineered merely for

heightened surface drama, one’s lived life is presented through a series of cliffhangers. This “reality” is easy to “consume”, even mindless, but what we are all paying in, without even realizing, is our attention—one of the most finite and prized resources in the age of “the attention economy”.⁴

Our attention is perpetually on a leash by the “content” created by the neo-liberal media and the creative industry. It turns everything into entertainment served into bite-sized morsels for quick consumption. It seems that we are now living in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.⁵ “In Huxley’s vision, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think,” writes Neil Postman. He argues that the much-feared Orwellian vision pales in comparison with the Huxleyan: “Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.”⁶

Creating meaning in such a world is hard-won. Fugitiveness becomes my refuge. The daily drudgery of independent filmmaking seems benign against the

I only have to descend from the mountain and the creative industry will cradle me with open arms.

discontent of “content” creation. This is not the time to churn the intoxicating soma-rasa from the banal, trivial, and the insignificant. This is not the time to produce sentimental spectacles and offer quick moral salvations. This is the time to wake people up to the widening chasm between us. “We need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide,” writes Franz Kafka. He challenges, “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.”⁷

That is the art I aspire to create. Cinema that is interventionist and transformative. Cinema that seeps into the blood and reaches every spore of consciousness. Cinema with responsibility, that creates an architecture of thinking; that asks questions of us and leaves us without any solace.

For

It is a miracle that such pursuits still get funded in a world largely enchanted by irrelevance. There are a handful of non-profit organizations around the globe, who find value in the work I pursue and fund it through non-recoupable grants. These fellow travelers are not the monarchs of yore who want a favorable portrait in return. Perhaps they agree with Mary Oliver that “those who are the world’s working artists are not trying to help the world go around, but forward.”⁸ Perhaps they value artists not as producers of commodities, but producers of culture. Perhaps they are happy to support artists to keep mining the meaning of human existence, standing at the edge of the unknown.

For the transformative cinema to bloom, artists cannot be status-quoist; we must be an “incorrigible disturber of peace” as James Baldwin declared. He added, an artist’s war with society is “a lover’s war” stressing that it is the artist’s responsibility to the society “that he must never cease warring with it.”⁹ This warring often places artists in the direct line of fire. This is the one time when the state loves fugitives. Welcoming them between the crosshairs. Making an example of them for the society to learn and behave.

Must we still annoy the autocrats?

Count the wreaths of war?

Maintain an account of facts?

Question the logic of capitalism?

Listen in to the dreams of the occupied?

Dance when our bodies desire? And sing when it is quiet?

I will do as much as an unlovable and ungovernable fugitive can do. I am a devout believer in art. It is also the highest order of commitment I am capable of. I will sing my cinema aloud, on my way up to the mountain that seems boundless. My feet recognize the grass they step on and the wild flowers they graze past. “Where the poet can sing, the people can live,” writes Baldwin, cautioning that, “when a civilization treats its poets with the disdain with which we treat ours, it cannot be far from disaster.”

So come, let’s sing, together.

1 Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet. Revised Edition. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2004).

2 Angela Carter, Shaking a Leg: Collected Writings (New York: Penguin Group USA, 1998).

3 Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost. (New York: Viking, 2005).

⁴ Michael H. Goldhaber (1997) Attention Shoppers! https://www.wired.com/1997/12/es-attention/

⁵ Aldous Huxley, Brave New World. (London: Penguin Random House, 1994).

⁶ Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. 20th Anniversary Edition. (London: Penguin Books, 2005).

⁷ Franz Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family and Editors. Paperback Edition. (New York: Schocken Books, 1990).

⁸ Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays. (London: Penguin Press, 2016).

9 James Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985).

the transformative cinema to bloom, artists cannot be status-quoist.

Virtual, physical—back to virtual, or was it hybrid?—and back to physical. From the browser to the metaverse to the regular big ol’ universe. In the sixteen years since IDFA DocLab first met the world, the field of emerging media and documentary storytelling has evolved many times over, as we hurdled through the age of the inter face to XR and sensory installations—though never in a linear journey. Whatever the paradigm, asking questions about reality through the art of non-fiction has always been central to DocLab, an evolving program in itself.

Over time, we’ve commissioned new pieces, initiated collaborations between artists, and tried to find common ground for a decentralized community. Five years ago, we officialized this Research & Development, attemp ting to traverse the ideological gap between art and the tech industry. In doing so, we acknowledge our nervous systems are at work—in every sense of the term—as we run up against a host of issues: control and dataficati on, medium-specific constraints, the overstimulation of some senses and the understimulation of others, and the precarious division of niche versus mainstream, to name a few. At DocLab, our response is to experiment, learn, feel, and explore. To sense. And now, we collage those senses with the help of some artists and thinkers who got us to where we are today.

Introduction by William Uricchio Interviews by Julia Yudelman

Introduction by William Uricchio Interviews by Julia Yudelman

The senses, our interface to the world, have every right to be nervous systems. They are notoriously unreliable. They learn to be efficient by filtering experience—the reason the untrained eyes of children see the sleights of hand in magic missed by the well-trained eyes of adults. They dull with age, requiring prosthetics like eyeglasses and hearing aids. They are culturally responsive, as media historians have argued, with sensory expectations, keeping pace with technologies that speed up, or slow down, or reverse, or amplify, or add depth to their representations. Indeed, as historians of a McLuhanesque-bent have described with regard to the West, they are epoch-defining—recasting reality as predominately aural (antiquity, where the spoken word prevailed), visual (the Renaissance, with its printing press, three-point perspective, and new literacies), and multisensory (the present, as we extend sight, hearing, and touch from the micro to the cosmic). And, they are pro foundly subjective, lacking a common language, calibrati on system, and ability to be shared.

“It is often said that seeing is believing. But we do not form our beliefs based on what we see; rather, what we see is often determined by our beliefs. Believing is seeing, not the other way around.”1 And with that, documentary film maker Errol Morris summarized the split between sensory input and sense as reason that has rippled across Western culture since at least 500 BCE, echoing the pre-Socratic philosopher Epicharmus who said, “it is the understanding that sees and hears, in contrast to the eyes and ears.”

Strange, then, that so many Western languages use the same word for the sensory apparatus (sense) and for understanding, intelligibility, and coherence (sense). We distrust our senses and take refuge in sense. Both sen

ses—like the tensions between them—are embedded in and reflect constant reorganizations of knowledge, social power, and the very idea of subjectivity and subject. And today, as humans increasingly serve as interfaces in operational, res ponsive, and synthetic media systems, those senses have taken a curious turn.

A new generation of media artists is interrogating these precarious sensory conditions. Moniker’s exploration of touch as it moves to friction, in an era of the “air gesture”, operates by retrofitting the senses; just as Polymorf’s experiments with smell reveal the interdependencies of sense and system, of life and the machine. Emilie Baltz considers interdependencies of a different kind, complicating familiar sensory clusters that we experience as taste, by calling out their constructed nature. Tamara Shogaolu’s explorations of the emotional resonance of low sound frequencies and Ana gram’s making visible the lenses of expectation that shape what we see, thus helping us see more clearly, complete the quintet of senses familiar in the West since Plato first introduced them.

Of course, as artists working with non-human systems continue to demonstrate, other senses abound. Ali Eslami’s consideration of the mediated sense of time and Rahima Gambo’s work with sensory co-presences bound up in space, like so many interventions at DocLab, address the vir tually real that is endemic in our emergent media systems. They confound the senses by simulating them, and they instill nervousness in systems accustomed to old realities.

¹ Errol Morris, Believing is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography (New York: Penguin, 2011), 93.

Smell is a very potent stimulus, but often it influences the brain on an unconscious level, triggering emotions and connections that were already there. Also, smell is data. The body uses it as a data set to change behavior depending on the smells it receives. So, for us, it’s just another button to push to create a stronger experience. Sometimes we use it more as ambiance—if you were to compare it to sound design—to stage a space or to emphasize a certain element in the space. Sometimes we use it as a special note to trigger you into a certain emotional state.

leasing scents and is integrated differently as hardware into the installation itself. We made these containers that are part of the suit you’re wearing. In the story world, these are a gland or exterior organs.

One aspect we really love is that the body is a chemical machine. It’s built out of chemicals. When you talk about media design, it’s mostly outside the body and it’s not chemical-based. You look at the screen, and the screen stays outside of you. In that respect, a lot of the media that we now create is quite clinical and sterile.

But the body is anything but sterile. It’s messy. It’s bio logical. It’s always in interaction with its surroundings. As soon as you work with smell, then, the medium gets into your body; it becomes part of your body. It makes the media more real, in the moment, and in space. That’s what we love about working with chemicals and smells and hormones; you open up the boundary between the medium and the body. You feel the source.

We also develop our own technologies to control smells. With Famous Deaths, we built the first version of a smell printer: A system that allows you to release scents on different cues in the story. Compared to Symbiosis is a way smaller, more compact way of re

Sound is the most important aspect of making immersive art. The body is a chemical machine.

To me, sound is the most important aspect of making im mersive art. It’s just the way we’re wired as human beings, and it’s been important since we started telling stories. When you look at the way we communicate, onomatopoeias add a sense of sound and sensory aspects to storytel ling. When you look at the history of cinema, adding sound was what took it to the next level. And even early on, when film was still silent, they had orchestras that played along in the cinema. So basically, sound is essential for being immersed in any type of storytelling.

What interests me especially is the deeper human connecti on to sound, depending on the frequency at which it’s being communicated. Low-frequency sounds are the ones that, for most humans, will give you an ominous sense, making us

thing you touch is your screen. You don’t touch for real. Somehow, the body, the physical, and the senses are com pletely neglected. So, we’re really interested in involving a physical component again.

In response to this lack of contact, we’re trying to design more friction using technology. In our research, we’ve found that apps and services are often primarily designed with the intention to remove friction—whether it’s Uber removing the interaction with the taxi driver or Google Maps removing the interaction with the physical map, so you don’t have to fight with your loved one.

But then within those frequencies, there are cultural asso ciations that come from specific sounds. The sound of a spoon in a cup of tea might create a memory of warmth, for was about asking: What do the se sounds evoke? In space, there is basically no sound, so I started wondering how sound designers in film were able to craft and imagine the sound of space, adding it for the pur pose of the story. Most of the films I found still use low-fre quency sound for space. Even though different cultures connect to different sounds, there were still certain universal connections—but the way that the sounds came together in these films to form a vision of the space was unique.

But we also saw that, actually, friction is the moment real interaction happens. We know that when there is friction, that is when something sticks to you, you remember. Then something happened that’s not so smooth that it somehow slips out of your fingers or out of your mind or away from your body. We think that the intention of designers and digital technologies to always remove friction represents a false promise. The responsibility of

“Touch” is a very broad word. And it’s now misused in saying “touching your phone.” The thing is, digital touch is very one-dimensional: it’s just touching your screen, and there are no real haptics yet in screens. So, this is what we’ve made a lot of work about—touching your phones,

We don’t want to be techno-pessimists, but there is not enough real interaction when we use digital technology. There’s a longing for real connections. When having Zoom conversations, when being social on digital platforms, when going shopping at home on your phone, the only

We should be friction designers.

Over the last few years, I’ve been interested in looking at my process in a non-human way. How can I introduce other ways of being in a space that are not limited by my body? Donna Haraway talks about this idea of tentacular thinking and how we can become more spidery in the way we occupy space or the way we collect infor mation. For me, it’s about making with and acknowled ging that I’m not the only presence in the room. I’m not the only person making this work.

can become softened or more porous; how it can allow things in and allow things out in that process of making that starts way before you begin a project and way after you finish it. I’ve been trying to shift my focus to the things that are not in the center of the frame.

The camera is a highly charged tool that was made with a particular function, and it has a history that is quite troubling in the spaces that I’m taking it to and using it in. So, one of the things I’ve been thinking about is how I can create extensions of the camera and extensions of the process of image-making.

I work in fragments a lot—whether it’s taking fragments of images and putting them together on a timeline, ma king a moving image piece, or an actual installation with objects. It’s something about this assemblage, working by assembling things together, where this starts to deve lop an intelligence by itself.

the screen, but I’ve been thinking about how the screen

It’s only at the end of that collecting process that you start to make sense of whatever patterns are happening, and a story starts to develop beyond what you had intended for that piece. It’s a sense of minimizing yourself in the process of making and acknowledging that there are other organizing principles at work—ones that have, I think, way more intelligence than you could even bring to that piece.

Time has medium-specific constraints. Looking at a painting can make you generate a sense of time within your own imagination. In literature, time is really fluid—it can be any form that the writer decides on, and then you conform to that. In film, the editing can define a page, traverse time, and unpack wider narratives. You can say “six months later” and it makes sense.

But with VR, it’s a whole different story. For me, VR is more about a sense of real-time—the present, the now-ness—and in that sense, the events are happening around the user. They often happen at a much slower

I’ve been thinking about how the screen can become softened or more porous.

pace than in film as well. Immersion in a VR experience makes us feel that time is being stretched.

It’s all about pacing. Compare an eight-minute VR experience to an eight-minute daily life experience—it’s nothing that eventful, but in an eight-minute VR expe rience, it can feel like a twenty-minute experience. We receive so many stimulants because the artist wants to say something or make you feel something. Our sensory system is being engaged at a seemingly unnatural pace, and this makes us perceive time differently, more like dreaming or hallucination.

From a maker’s perspective, it all comes down to thinking of time as an ingredient. Pace however you want to when you’re laying out your story or concept to viewers. Right now, I’m involved in contemporary art and installation making, and this is a new way of seeing time for me. In a screening situation, you sit down and

start to watch from beginning to end. But if you watch video art in a gallery, it’s playing on a loop, and you dip into it at random parts of it. That’s something I always have to think about: When someone enters the room halfway through, or towards the ending, what do they get out of it? What is that experience?

In the end, time is one of the most ambiguous things, almost like a black box itself. Of course, whatever we’re talking about now is not time itself, but the implications or implementations of it within art, because that’s how we explore things naturally. It’s through this experience that we have an idea that is embodied within us—our own understanding and the limitations of our senses.

For me, VR is more about a sense of real-time—the present, the now-ness.

Wrestling with sight is the battleground of meaning. Basi cally, we are always battling against the fact that we see what we expect to see, or what we want to see. Maybe because we started out as filmmakers shooting films, we are more interested in seeing as the process by which you perceive, judge, and place yourself in the wor ld—rather than just a thing that happens when you blink your eyes open in the morning.

So, making work can often be about creating a process of alienation and then acclimatization—alienation from your normal experience of the world through attending to how you feel at each stage of participation. Noticing your desire to leave as a kind of pull in your stomach, or the feeling that you’re being watched as a kind of sensati on that ripples over your shoulders. These are embodied techniques to move towards seeing your own (learned) responses, and they also require a brutal sort of honesty about experience design.

Our VR piece Goliath is an experience about psychosis, but it’s also about the illusion of reality that you’re not aware you place trust in—and how that trust in your own sense of what’s real can be played with. This habitual illusion allows you to conceive of psychosis as an extreme experience that is unrelatable.

Messages to a Post Human Earth is about how we can’t see the natural world for what it is—we think of it as a back ground façade to our existence. You have to slow down and observe that judgment as it happens, and then look again. We are now working on Ghosts of Solid Air, a project about statues and public space. By getting entangled in a story, the project’s intention is to see these judgments again, afresh—to stop unseeing them—and to see the impact they have on our lives, in terms of who is and who isn’t celebrated.

Immersion itself is only really possible because we’re always filling in the gaps—ignoring the holes and taking pleasure in the surrender. Which we do all the time, anyway. All our pieces are in some way trying to get you to notice your habits, expectations, and beliefs for what they are—the lens through which you encounter the world, the lens you are attached to. The lens which it is so hard to see, let alone let go of.

We’re always battling against the fact that we see what we expect to see, or what we want to see.

MAY ABDALLA AND AMY ROSE (ANAGRAM)Messages to a Post Human Earth by May Abdalla and Amy Rose (2021).

The interesting thing about taste is that it’s the only human sense that is a confluence of all the senses. Taste is not taste—taste is flavor. And flavor is a combination of sight, smell, sound, and touch. That’s primarily why I’m interested in it, because what it does is it leads us to a question of how we craft our perception as people.

craft meaning and how we tell stories. What happens when we change our sense of sight? What happens when some thing is a different color when you’re tasting it? What does it mean to us? How do we experience that? Instead of there being a declaration or any kind of meaning, what it does is it questions meaning because it questions our construct. And that, for me, is one of the most fundamental human experi ences to play with: As we go through our lives, how do we craft meaning, recraft meaning, deconstruct meaning, and reconstruct meaning?

A simple exercise: If you plug your nose and you eat some thing, you realize you can’t taste anything. So, without our sense of smell, we have no sense of taste. If we change the texture of something, that starts to play with our percep tion and our definition of everything from freshness to decadence. It’s an orchestra of meaning, and that’s what I’m interested in from the human perspective—how we

I think that in today’s day and age, there is more need for that than ever before, as our world slowly becomes undone and undone and undone. You see so much culture trying to make meaning. And with taste, because we’re so implica ted in it on a regular basis—one, two, three, four, five times a day depending on who we are, where we live, and how much money we make—there’s a real opportunity there to play with greater sensitivity, kind of like a little training ground for exploring how we might start to make, remake, and deconstruct the meaning of our lives.

It’s an orchestra of meaning, and that’s what I’m interested in from the human perspective.

#9

#1 THE SENSE OF MENTAL OR SPIRITUAL DISTRESS. Diagnosia by Mengtai Zhang (2021). Is “internet addiction” really a psychiatric disorder at all? This VR experience raises big questions about that claim, revealing a diagnosis of “internet addiction” could just be another form of social control.

#2 THE SENSE OF PROCREATIVE URGES: SEX AWARENESS, COURTING, LOVE, MATING, CHILD REARING. [Posthuman Wombs] by Anna Fries and Malu Peeters (2021). An interactive VR experience that explores pregnant bodies by expanding horizons and perceptions, aiming to reshape dominant representations of pregnancy.

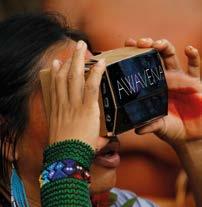

#3 THE SPIRITUAL SENSE: CONSCIENCE, SUBLIME LOVE, ECSTASY, SIN, PROFOUND SORROW, AND SACRIFICE. Awavena by Lynette Wallworth (2018). The Yawanawá in the Amazon have medicines with the power to take you to places you have never physically been. Created in close collaboration with them, this experience uses VR as medicine to transport you to their world, guided by the first female shaman.

#4 THE SENSE OF MOTION: BODY MOVEMENT, SENSATIONS, AND SENSE OF MOBILITY. THE SENSE OF SPACE OR PROXIMITY. THE SENSE OF ONE’S VISIBILITY OR INVISIBILITY. Vast Body 22 by Vincent Morisset (2019). This collaborative experiment on movement interprets your behavior and distills this continually changing input into a projection of a body that moves fluidly with yours, yet fluctuates continuously between different bodies and identities.

#5 THE SENSE OF FEAR, DREAD OF INJURY, DEATH, OR ATTACK. Die with Me by Dries Depoorter (2018). In this chat app, you can only enter when you have less than 5% battery. Die together in a chatroom on your way to offline peace. Here people exchange their last thoughts, regrets, and wishes with others who are in a similarly critical condition.

#6 THE SENSE OF SELF, INCLUDING FRIENDSHIP, COMPANIONSHIP, AND POWER. The Space Between Us by Benedicte Kurzen, Sanne De Wilde, Tong Wu, and Barak Chamo (2019). An exploration of the often-concealed spaces between human and machine, privacy and surveillance, the self and the other, the observer and the observed, or our real bodies and digital representations, experienced as an interactive installation.

#7 THE SENSE OF BRAIN WAVE AWARENESS AND DREAMING. Brainstream by Caroline Robert (2021). In this interactive animation, you give a stranger a virtual brain massage. This intimate act evokes a stream of emotions and memories, and offers an original glimpse into the workings of the brain.

#8 THE SENSE OF MIND AND CONSCIOUSNESS OR COLONIZING SENSE, INCLUDING RECEPTIVE AWARENESS OF ONE’S FELLOW CREATURES. Everything by David OReilly (2017). At first, you’re a bear. Then a fir tree, then a succulent, and then a rock. From a single-celled organism to an entire solar system, the player of this interactive video game can take on any identity. It makes no difference what you choose, because everything is part of the same energy source.

#9 THE SENSE OF EMOTIONAL PLACE, OF COMMUNITY, BELONGING, SUPPORT, TRUST, AND THANKFULNESS.

Ferenj: A Graphic Memoir in VR by Ainslee Robson (2020). During a pointillist VR flight through director Ainslee Robson’s memories of Cleveland and Addis Ababa, cultural dislocation and the elusiveness of her Ethiopian-American identity become palpable.

#10 THE SENSE OF LANGUAGE AND ARTICULATION, USED TO EXPRESS FEELINGS AND CONVEY INFORMATION. Saravá by Pedro Rodolpho Ramos (2021). A soundscape of voices, sounds, and noises of nature generate abstract visualizations, creating audiovisual music in a meditative dome film that merges multiple languages under a single roof.

5Our Notes on a festival should not be considered as complete without some documentation of the IDFA 2022 edition itself. A register of the filmmakers, artists, visionaries, and collaborators who gave shape to our program. A snapshot of the 35th edition of IDFA, which happened in the city of Amsterdam in the year 2022.

Whether that is here and now, or maybe—by the time you pick up this booklet again—already a decade ago. It’s the stuff we hope you’ll hold onto and keep safe in your own archives. Stored quietly on a bookshelf somewhere, a festival object. A piece of printed matter, ready to be held again.

A piece of printed matter, ready to be held again.

As always, IDFA presents a robust talks program for audiences and industry alike. Hundreds of encounters with filmmakers who define our current era. Industry leaders who set the agenda—and push it forward. Protagonists with a story to tell. Experts chiming in with a different view. Audience members with burning question to ask. Whether it’s a short chat after a premiere or a deep dive into an entire oeuvre, there’s much to discuss at this festival edition.

On the following pages we present a curated glimpse of those conversations. What we hope you’ll look back on. For the complete schedule of all talks, refer to our website or printed program guide.

In an in-depth public interview, Artistic Director Orwa Nyrabia talks to Laura Poitras about her rebellious creative trajectory, Top 10 favorite films, and the political power in documentary art. Long prolific in the spheres of docu mentary and journalism, Poitras’ fearless filmmaking has changed the world as we know it. Her film My Country, My Country examined the US occupation in Iraq; The Oath shed light into the dark core of America’s war on terror; the Oscar-winning Citizenfour beared witness to Edward Snow den’s unfolding whistleblowing campaign; and Risk (2016) portrayed WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Her films have marked dramatic milestones in recent history, while creating a film record of the US government’s civic rights violations. Laura Poitras has also taught filmmaking at Yale and Duke University, shared a Pulitzer Prize for public service with her reporting on the N.S.A.’s mass surveillan ce, and has been on the board of the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

Her latest film is All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which won a Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival 2022.

An in-depth conversation with filmmaker and scholar Emma Davie. Together with writer Pamela Cohn, she will discuss her body of work, artistic choices, and views on cinematic art.

This insightful session will also include excerpts from Da vie’s various works as well as her new film The Oil Machine. Emma Davie’s filmmaking practice centers around profound creative collaboration both in front and behind the camera. In her work, she often experiments with narrative approaches and complex relationships between the obser ver and the protagonist. After directing a number of suc cessful documentaries for television, including What Age Can You Start Being An Artist?, Gigha, Buying Our Island, and Flight, Davie co-directed I Am Breathing which won a Scottish BAFTA for Best Director.

Another important inspiration in Davie’s career is per formance theater, which shaped so much of Becoming Animal, a film she co-authored with Peter Mettler in 2018. Emma Davie served as a documentary programmer for the Edinburgh International Film Festival, was on the board of EDN, and currently runs the postgraduate course in documentary directing at Edinburgh College of Art.

An inspirational, in-depth hour-long conversation with renowned Indian filmmaker Nishtha Jain. Moderated by writer Pamela Cohn, this talk will focus on Jain’s creative credo and body of work, featuring excerpts from both The Golden Thread and earlier films. Nishtha Jain’s cine ma explores the political in the daily, and sheds light on the mechanisms of invisible oppression. Her films peer into the cultural constructs like privilege, cast, class, and gender, revealing their omnipresence in contemporary Indian society.

Jain has also been working across various platforms including scripted film and virtual reality installations. Among the works to be discussed during this filmmaker talk are some of her most known documentary titles: City of Photos (2004), Lakshmi and Me (2007), and Gulabi Gang (2012).

An inspirational, hour-long conversation with Petra Latas ter-Czisch and Peter Lataster. Writer Pamela Cohn speaks with the renowned directors about their impressive filmo graphy, views on cinematic art, and approach to working as a creative duo.