2 minute read

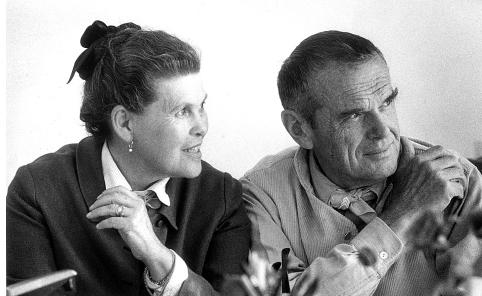

Past, perfected: Problem Solving with Ray & Charles Eames

Llisa Demetrios’ childhood memories are a design junkie’s dream: she often found her grandfather, Charles Eames, up on a crane, figuring out shots for the iconic film “Powers of 10.” Grandmother Ray Eames, in a deep-pocketed dress of her own design, gave hugs that smelled like roses and had a workshop full of papers collected from around the world; objects and ephemera filling drawer after drawer. Endless iterations of furniture legs and seats — the designs that almost made it — were everywhere. / It was, undoubtedly, a magical glimpse into the world and creative process of two of design’s most revered figures. But within the fertile creative ecosystem of the Eames workshop, something else was at work: a system of imaginative problem-solving that has incredible resonance for designers and creatives working today. /As chief curator at the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity, Llisa both preserves her grandparents’ legacy and shares it within the context of their unique methods. “Our goal at the Institute today is really to unpack the way Ray and Charles solved problems,” she says, “the way they infused every one of their designs with discovery and curiosity at every turn.” /With thousands of artifacts from the Eames workshop to catalog, (work that is still ongoing today) Llisa has spent decades immersed in the clues Ray and Charles left behind. Based on her learnings and her own experiences with her grandparents, she has assembled lessons from their prolific process, to share with the world.

Find knowledge (and inspiration) everywhere

Advertisement

Fueled by insatiable curiosity, the Eameses were continuously learning. Among the multitude of objects they studied as observers and collectors of design were kites and childrens’ toys, which exist today as part of their archive. They also sought knowledge of processes and technique from unlikely sources — including workmen who might have been called to repair something in the workshop, but found themselves walking “the long way to the kitchen sink.” A trip through the workshop, the Eameses reasoned, might prompt a discussion about their own projects in progress; and in turn an exchange of useful ideas from the repairman’s practical and experienced point of view.

Turn criticism into problem solving

Walking home from dinner with her grandfather, Llisa recalls being asked how she enjoyed her meal. The dinner, which included borscht, didn’t exactly rank high on an 8-year-old’s list of favorites. Charles’ response to her criticism? “He said ‘What would you have done differently?’” That question turned her dislike into an exploration of materials, techniques and possibilities, and aptly taught the lesson “don’t just complain, come with a solution.”

Design with iteration in mind

Good design remains responsive to changing needs and conditions; which is why the Eameses continued to refine even their most successful pieces, even after they entered production. For them, iteration was a key part of an open-ended design process, either used to take steps toward a better solution or to confirm that initial thinking was correct. Eight variations of a chair leg might be created, only to return to the first variation: “You had to make the other seven to know that the first one was the right one.”

Intend to inspire

Though the Eames brand is known for pieces of exquisite function as well as both visual and physical longevity, they also designed pieces intended exclusively to spark human curiosity, emotion, imagination, and a sense of play. Their Musical Tower, a 15-foot, vertical xylophone which plays when a marble is dropped into a slot in the top, was originally designed for the Time-Life Building. When it proved too popular with tenants, it found its way back to their studio. A design for an intended national aquarium in Washington, D.C. inspired the Eameses to create a design that they hoped would spark curiosity and empathy — allowing humans to see and want to protect the otherwise largely invisible inhabitants of the ocean. Eventually, though the original commission was never built, their plan for such an aquarium informed the design of several major aquariums in the United States, serving the Eameses’ intent by imparting a love of the ocean to millions of visitors.