6 minute read

Darkness

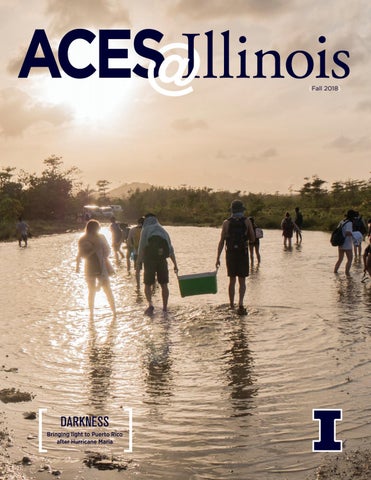

DARKNESS

Advertisement

Bringing light to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria

By Jennifer Shike as told by Luis Rodriguez

December 15, 2017

It is dark here.

As I exit the airport, I find myself surrounded by total darkness. My flight arrived late. Now, the dusk has quickly turned to night. Most of the street lamps are out—the houses are mere shadows against the black sky. I can hardly see a thing, but I can tell that the damage is extreme. There is so much to be done, so many problems that need solutions.

My mind snaps back to September 20, 2017, when the worst storm in recent Puerto Rico history decimated the island with sustained winds of 155 mph, uprooting trees, downing weather stations and cell towers, and ripping wooden and tin roofs off homes. Electricity was cut off to 100 percent of the island, and access to clean water and food became limited for most of Puerto Rico’s 3.4 million residents, resulting in one of the biggest humanitarian crises ever.

So, I’m here on a mission to help in some small way. The first person to suggest that I redesign my regular Puerto Rico study tour was actually a student. (Those students always have the best ideas.) I quickly discovered a mass of students interested in pursuing this adventure with me. My goal is to find out how we can begin making a difference.

All I know for sure is that we have a lot of work to do.

ASSESSING THE NEED

Luis Rodriguez, professor of agricultural and biological engineering, spent many years of his childhood in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, and several communities around the island. It was a natural fit for him to lead study abroad courses to the island, and now, after the hurricane, to develop his latest course: “Disaster Relief Projects: Hurricane Maria.”

Almost half of the residents of Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, live below the poverty line—by far the highest rate of any U.S. state or territory—and the unemployment rate is nearly three times the national average.

“During my trip back to investigate the aftermath of the hurricane, I was amazed by the range of what I witnessed,” Rodriguez says. “On one hand, I saw the ubiquitous signs of a recent disaster, and on the other hand, a quiet optimism about the recovery.”

For eight days, he toured the countryside and the urban centers, observing how the people and businesses were clearing away the debris Maria left behind. Piles of downed trees, construction elements, and other garbage comprised makeshift landfills along the roads.

“We needed to help them find a way out,” he says.

Rodriguez met with collaborators, both old and new, at the Universidad de Puerto Rico Recinto de Mayagüez (UPR-Mayagüez). He easily found people interested in contributing to the effort: engineers from several specializations, economists, and scientists from nutrition and dietetics.

“It’s important that the participants in the study abroad trip have real access to people working and living the experience,” he says. “My closest UPR-Mayagüez colleagues are living in darkness while carrying on with teaching classes and conducting their research during the day.”

With nearly every sector of Puerto Rico’s economy and infrastructure suffering after the storm, Rodriguez thought, why not take advantage of the opportunity to engage in the perfect academic exercise?

“Puerto Rico has been forced into a renewal process,” he says. “Future classes will tackle the challenge of assessing and developing suggestions for rebuilding an entire industry into its ideal state from ground zero. The list of high-impact learning experiences and possibilities is endless.”

AN ENLIGHTENING EXPERIENCE

On March 17, Rodriguez boarded a plane for Cataño, Puerto Rico, with 37 students and three staff for a nine-day journey. The goal: identify resilient responses to the recent disaster. They met up in Puerto Rico with staff from Amizade, a global service-learning organization that helped Rodriguez identify the opportunity to work with Caras Con Causa, the local group who hosted the Illini. Together, they all set out to investigate the cultural, political, and social factors that preceded Hurricane Maria and that currently influence sustainability and viability of solutions.

Motivated by a variety of life experiences and goals, the students on this trip discovered common ground in their desire to help. The hurricane provided them a tragic opportunity, Rodriguez says.

Prior to their departure, students learned how to assess potential solutions for challenges local communities may be facing after the disaster. They also received training about the safety issues associated with entering potentially dangerous areas.

“Primarily, we worked in ecosystem restoration at Cataño,” Rodriguez says. “We cleared invasive species, prepared the soil for mangrove transplants, and worked on the restoration of a nursery to promote a healthy ecosystem in the neighboring Las Cucharillas Nature Preserve.

“A healthy ecosystem will have more potential for flood mitigation. The Juanna Matos neighborhood of Cataño is quite flood prone for a variety of reasons, including the overgrown Cucharillas.”

The students performed infrastructural assessments in the Juana Matos and Puente Blanco communities of Cataño. They also assessed two dairy farms in Hatillo and Camuy and a nature reserve in Manatí. Rodriguez says infrastructure encompasses many factors. Around a community, especially when considering the aftermath of Maria, this primarily refers to inadequate drainage that might have exacerbated flooding. At the dairy farm, it also includes shelters, watering structures, manure handling, and dairy parlors. It may also include electrical infrastructure, roadways, fencing, canals, signage, utility poles, and structures, among many others.

In an infrastructural assessment, a community is surveyed using the Fulcrum web application to take photos or videos of the locations of infrastructure concerns. The web application allowed students to annotate a report, including GPS locations and details regarding the problems, while incorporating imagery. Students later reviewed all these assessments and created a set of four reports, including recommendations for next steps in a longerterm recovery for the sites they were able to visit.

Aya Bridgeland, a junior in crop sciences, says that she expected Hurricane Maria’s damage would impact agricultural systems, but she had no idea that it would affect food availability and security across the entire island.

“I was surprised to see how much agricultural systems were suffering, even six months after the hurricane,” Bridgeland says.

Because Puerto Rico does not produce most of its own food, when shipping and related transportation infrastructures are down because of an unforeseen disaster, the immediate result is insufficient food to feed the island's population.

Bridgeland says, “Learning about Puerto Rico’s food security problems caused a massive shift in my thinking. When Americans think about food security, we often look at faraway places removed from our own experience, like sub-Saharan Africa or southeast Asia. Now I realize I was blind to the struggles of Americans who also suffer from food insecurity and deserve just as much help and aid as anyone else who is hungry.”

The students were impressed with how the Puerto Rican communities came together to tackle various problems, Rodriguez says.

Katherine East, a sophomore in political science, says, “I think that the most important thing that you can do while abroad is to recognize that you live behind a filter built by your own identities and perceptions of the world. Once you recognize that, it allows you to challenge what you think you know.”

REFLECTIONS

This course is just the beginning of a bigger opportunity to make a difference in the world, Rodriguez says. After the trip, Rodriguez’s primary colleague at UPR-Mayagüez used the students’ reports to develop a summer practicum for his own students. And this fall, four U of I students will undertake independent study coursework to continue the project. If all goes as planned, Rodriguez will offer the course again; the hope is to take a group to Puerto Rico in summer 2019.

“If we do our job well, we can be responsive to many such unfortunate events around the world,” he says. “There is no doubt the students have the desire and energy. The only thing we need is a local network on the ground—we had this without much trouble in Puerto Rico.”

March 26, 2018

I’m back in the United States now, but Puerto Rico will always be home. I hope this is the start of something bigger than we can imagine. I hope my students learned that their time, effort, energy, ideas, and desires matter.

I want them to recognize that the skills they are developing here at the University of Illinois are broadly applicable to a variety of environments. I hope this course helped them emerge better prepared to understand the influences of local factors, such as culture, when seeking to solve problems and act as change agents.

It makes me proud that this can be in Puerto Rico—but if I am honest, it can be anywhere. The world is waiting for their bright ideas to break up the darkness.