Sky at Night

THE

THE

Your guide to the US event

PLUS See and image the sunset phases from the UK

HOW WE KNOW THE AGE OF THE COSMOS

AI SEEKS HABITATS FOR HUMANS ON MARS

LIGHT POLLUTION SOLUTIONS:

MAKE YOUR HOME SKIES DARKER

WHERE IS EARTH? DISCOVER OUR PLACE IN THE UNIVERSE

TESTED: MASUYAMA’S HIGH-END EYEPIECES

These two interacting galaxies are awash with bright young stars

HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE, 26 JANUARY 2024

The two blue beauties seen in this picture are NGC 5410 and UGC 8932, a pair of interacting galaxies that can be found some 180 million lightyears from Earth in the constellation of Canes Venatici.

NGC 5410, the larger of the two, is a barred spiral galaxy that was first observed by William Herschel in 1787. It measures 80,000 lightyears across and, like its smaller companion, has a distinctly blue colour. That’s because both galaxies are rich in young, hot stars. Blue stars are hotter than red stars such as our own Sun, and because they emit more energy, tend to be shorter-lived.

The unusual shape of UGC 8932 is believed to be due to the gravitational pull of its larger companion.

Follow our tips to find out how to really see glorious galaxies like M81, Bode’s Galaxy, in this spring’s skies

Rod Mollise invites you on a tour of seven spectacular spring galaxies around Ursa Major and shares his tips and tricks on how to see them

Spring has come to the Northern Hemisphere. The great globe of the heavens has rolled on and the brilliant star clusters and nebulae of winter are sinking in the west. It’s now that deep-sky observers turn their attention to the subtler marvels on the rise – the galaxies. In the north, the Great Bear, Ursa Major, and its neighbouring constellations, Canes Venatici and Coma Berenices, are riding high. The

area is home to countless island universes, some of which will be our destinations tonight.

No object in the sky is more harmed by light pollution than galaxies. The first thing you learn about galaxy observing is: the darker the sky, the better. Many can be seen in suburban skies, but to see details, to observe anything in most galaxies other than their bright central regions, you’ll need to get to the darkest location you can access.

Dani Robertson explains how simple changes at home can beat the scourge of light pollution

They say that home is where the heart is, but is your home where the lights shine? Electric lighting has changed the way we live, and lighting technology has advanced to the point where we can now hold the power of thousands of candles in the palm of our hands. Artificial light at night (dubbed ‘ALAN’) has created its own empire in little over a century, and very few places are left on the globe that have escaped its growing, glowing campaign.

Between 2012 and 2022, light pollution increased globally at a rate of 7–10 per cent each year. The situation is so dire that many places are now working to protect their night skies, such as the newly appointed Dark Sky Community of Presteigne and Norton in Wales, conquering light pollution in an incredible show of community spirit.

revealing themselves, destroying your night vision and wrecking your stargazing plans.

When it comes to light pollution, every bulb counts. We all know how frustrating an ill-placed streetlight can be when it comes to our own personal experiences of trying to stargaze from home. Light pollution from those individual bulbs accumulates, creating a much bigger issue that impacts us all. This dome of light covers our towns and cities as the wasted light from millions of unshielded bulbs shines upwards.

Due to the low cost of LEDs, lights have crept into places once safe in the shadows. Daffodil bulbs are being replaced by the glowing LED bulbs of decorative lights in our flowerbeds, from which only light blooms upwards. From rooftops and rafters hang 1,000-lumen floodlights, the silent enemy of backyard astronomers. They wait until you’ve assembled your telescope and tripod with frozen fingers and battled to align with your target before

It’s bad news for astronomers, both amateur and professional.

A Royal Astronomical Society study recently found that two-thirds of the world’s largest professional observatories are impacted by light pollution and no longer have natural levels of darkness. If we can’t protect the workplaces of our professional astronomers, what hope have us amateurs in our back gardens and urban parks got?

It’s not only astronomers affected. Light pollution is increasingly recognised as a major impactor on human health. As a disruptor to our circadian rhythm, it has been linked to increases in insomnia, diabetes and cancers. Medical studies have found those of us living in more light-polluted

Take some practical steps today and begin to reclaim your view of the stars

The first group of people to bring attention to the growing problem of light pollution were astronomers.

At no point in our history have we produced and consumed light more than we do now, bringing an increase in light pollution at an alarming rate, with impacts on our health and the environment, especially nocturnal biodiversity. It has also reshaped our perception of not only the night sky, but also the night.

However, protecting dark skies is a labour of love that relies heavily on collaboration, and the number of people focusing on this topic has never been greater. Thanks to the growing pool of committed people and communities, we have never been better equipped

to tackle light pollution. Unlike other pollutants, it’s relatively easy to eliminate light pollution and its adverse effects: switch it off and the problem is gone.

That is easier said than done, however, because light pollution is not just an environmental problem, it’s also a cultural problem. Even the terms we use, such as ‘brightness’ and ‘darkness’, can be very subjective from both cultural and individual perspectives. Mechanically, it may be easy to switch something off, but culturally doing so is challenging.

The challenge is greater today because we live in the age of light, when the majority of the surfaces we interact with emit it, and it is widely accepted that illumination is excessively consumed as a visual embellishment, celebration and communication tool. Lighting is treated

as a silver bullet to all societal issues. However, there is still no strong evidence that proves that, for example, more light deters crime after dark.

For these reasons, as a lighting designer I’ve sought to develop practical precedents for the judicious and considerate use of light, and make them work with the help of committed, inventive communities striving to restore and protect their dark skies. In the quest to install illumination that respects the night, it’s crucial to make the process inclusive, so that everyone involved takes part throughout the project, not merely after it has been finalised.

So let’s explore three community projects and the ways in which dark sky spaces can be beneficially designed with, and for, the people who live in them.

The fundamentals of astronomy for beginners

As a total eclipse crosses the US on 8 April, Pete Lawrence explains how to photograph the event from within the path of totality

Photographing a total eclipse of the Sun is exciting. To make the most of it, though, requires some pre-planning. In this article, we’ll suggest ways to make it as enjoyable and stress-free as possible. If you’ve never photographed a total solar eclipse before, trying to catch everything that happens may be overambitious. Instead, only tackle what you’re comfortable with and do plenty of rehearsals, as then you’ll be able to fully enjoy the day.

First, let’s think about kit. Many different imaging devices can record an eclipse, but the demands of travelling to a specific location typically mean

Don’t be in the dark when totality arrives! Follow our guide to capturing one of the astronomical spectacles of the decade

that self-contained units such as DSLRs are popular. Plenty of charged batteries and SD memory cards are a must, as well as a reliable remote shutterrelease cable to avoid shaking the camera. A back-up camera body is also handy if you have one, just in case!

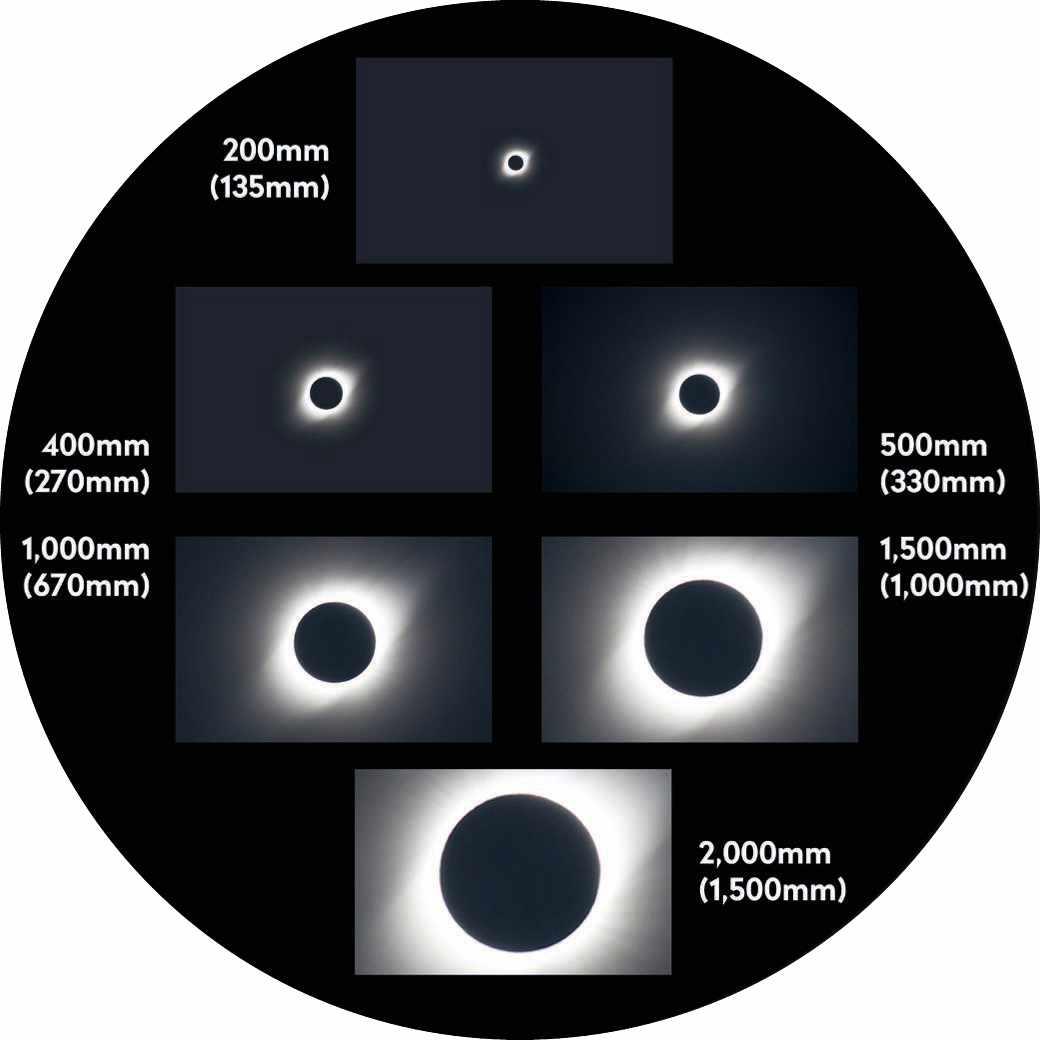

The big kit decisions are usually which lenses to use and how to mount the camera. Lens focal length dictates image scale: a long focal length gets you close in on the eclipse, but it means you’ll have to keep everything centred. It also restricts coverage of peripheral sky targets such as stars, planets and the solar corona. A short-focal-length, wide-angle lens

First contact

Make sure your solar filter is fitted (it can only come off for totality) and your exposure set correctly as the show begins

Partial phase

A good time for shots of the crescent cast through a pinhole, eg a colander

Second contact

Baily’s beads, diamond ring effect and the chromosphere

allows you to capture the bigger picture, but if it’s too wide it will produce a rather tiny eclipsed Sun.

Your choice of mount is usually dictated by travel restrictions, a simple tripod being easier to carry than a heavy equatorial mount. Both work for an eclipse, but a tripod will require constant adjustment to keep the target centred. The most important thing here is to choose a stable and easily adjustable mounting solution.

One essential piece of equipment is a solar safety filter. This can be a DIY variety made from certified solar safely film, or it can be pre-bought. Bear in mind that the filter has to be both securely fitted and quick to remove during totality. Before using any solar filter, it’s important to check that there are no pinpricks letting through light; it’s a good idea to have a backup in case of damage. You must also, of course, wear certified eclipse glasses to protect your eyes.

There are three distinct stages to a total solar eclipse: the initial partial phase; totality; and the second partial phase. The solar filter must be fitted during both partial phases and so must be replaced after totality – it’s very easy to forget after the excitement! The stages are, in theory at least, determined by eclipse contacts. The initial partial phase runs from first to second contact; totality from second to third; and the last partial from third to fourth contact as the eclipse ends. The reality is slightly fuzzier.

Totality

The corona, prominences, stars and even planets appear

Third contact

A second chance to get Baily’s beads and a diamond ring

Partial phase

An opportunity to attempt shadow bands and to capture the scene around you

Fourth contact

After the Moon’s last moment of contact with the Sun, full daylight returns. The show is over

Best of three: with so much happening, it may pay to focus on the key moments around totality

Decisions, decisions: how the eclipse will appear depending on the focal length of the lens you choose

The partial phases are mirrors of one another, both requiring a solar filter to be used. Focus accurately, using any visible sunspots or else the Sun’s edge. Use a lowish ISO and, if using a lens as opposed to a telescope, set its f/number to around 8–11. Adjust the exposure to deliver a bright but not over-exposed Sun, using the camera’s histogram or overexposure meter to check this. Take shots at pre-defined intervals, but don’t set the interval so short that you’ll be tied to your camera. Don’t forget that you want to enjoy the experience too!

The ‘zone of panic’ describes the central portion of the eclipse, from just before to just after totality. This period contrasts dramatically with the relative calmness of the partial phases. With lots of phenomena happening in quick succession, you’ll need mental focus and dexterity to see and capture them. A popular image to capture during the latter stages of the initial partial phase (or during the second partial phase, if you miss it the first time!) involves a piece of card or an object with one or more 1–2mm holes in it. This is used to cast a shadow onto a piece of white card, each hole producing a tiny eclipsed Sun image. Colanders and tea strainers are ideal for this. Another to try is as the Sun’s crescent becomes thin; it then acts as a curved slit of light, causing shadows to appear sharp in one direction and fuzzy

April 2024 BBC Sky at Night Magazine 39