7 minute read

Growing Greener: supporting wildlife

Growıng Greener

Support wildlife to boost diversity

Our gardens, whether they’re tiny city yards or spacious rural retreats, have the power to reverse the decline in biodiversity, says Jeff Ollerton – all it takes is a few tiny changes

Professor Jeff

Ollerton is a consulting scientist and writer, and visiting Professor at the University of Northampton

The wildlife that surrounds us

has changed a great deal in the past 10,000 years. Much of that change is natural, as species come and go across the landscape, driven by unfathomable natural processes. Did you realise, for example, that the collared dove was virtually unknown here prior to the 1950s? Something prompted its population to expand from the eastern Mediterranean and across the rest of Europe, until now, when it is one of our most familiar garden birds. Recent changes to wildlife, including the loss of insects and the near-extinction of other birds, are however due mainly to human pressures on the environment. There have been some success stories, including the reintroduction of the red kite and the chequered skipper butterfly, but the balance is still negative and we continue to lose biodiversity at an alarming rate.

Why should this matter to gardeners? What does it have to do with us?

We all have an environmental impact, but that also means our actions can make a big difference

It matters for several reasons. All of us are part of the problem: we all have an impact on the environment, but that also means our actions can make a big difference. More fundamentally, our society relies on nature for our health and wellbeing, and for our economy, in very tangible ways.

Some of the actions that gardeners may take for granted, such as using peat-based composts, bug sprays and herbicides, have direct and indirect impacts on wildlife. Although retailers are phasing it out, peat is still widely used in the horticultural trade. Much of this is imported from eastern Europe, where the destruction of peat

Greener facts

L An estimated 70% of

insect ‘pests’ spend part of their lifecycle in the soil. Robins are attracted to gardeners at work because they know we’re likely to disturb the soil, allowing them to feed.

bogs impacts local wildlife and releases stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Using chemicals to kill pests and weeds may make your garden tidier, but it also removes important nectar and pollen plants that are needed by bees and other pollinators, as well as the insects and seeds that are food for birds.

This sounds a little depressing, but the role of a gardener can also have a positive effect. This is most obvious in towns and cities, where gardens act as green oases. But gardens are also invaluable in rural areas, where they may be the most wildlife-friendly habitats in an otherwise intensively farmed landscape. And it doesn’t have to be a large plot of land: even a small window box, hanging basket or tub, if planted with the right kind of flowers, can make a local difference to pollinators.

A healthy, thriving garden is one that’s full of birds that eat the pests, humming with insects that pollinate our crops, and bursting with wild plants that provide food for those pollinators and birds. It’s a garden that has year-round interest – what could be more beautiful in winter than colourful goldfinches and perky dunnocks taking advantage of the seeds that our plants have left behind?

A garden like this is an ecosystem, part-natural and part human-made. It’s something that people have been doing for thousands of years, and by being pro-active about the wildlife in our garden, we’re helping to ensure that this wildlife will still be around for our descendants long into the future.

Greener facts

L Some pest controls, such

as those derived from pyrethrum, still harm wildlife, despite being classed as organic.

L Herbicides kill weeds,

insecticides kill insects and fungicides control fungal diseases: using theth wrong one is pointless.

growing greener Wildlife needs water

Kate Bradbury, GW Wildlife Editor and member of our Growing Greener panel, explains why water matters

All species need to take in water, while birds need it to bathe in, and aquatic insects and amphibians use it for breeding.

Summer is no longer the only typically dry season; the last two springs have seen few ‘April showers’. Drought-stressed plants produce less nectar, and if leaves shrivel, caterpillars suffer, too. This has effects up the food chain, and any check in the breeding cycle can start species on the slippery road to extinction.

There’s plenty you can do. Keep bird baths topped up and leave a water dish for mammals. Use your water butt to top up your pond, and grey water to keep your plants producing nectar. Popping a large stone in a bird bath will help protect insects in search of a drink, too.

IMPROVING WILDLIFE DIVER SIT Y

It’s not hard to make simple changes to our gardens and create places of value for the wild creatures in our neighbourhoods. Get started now with a few modifications that will encourage more creatures to visit and stay.

Take it to another level

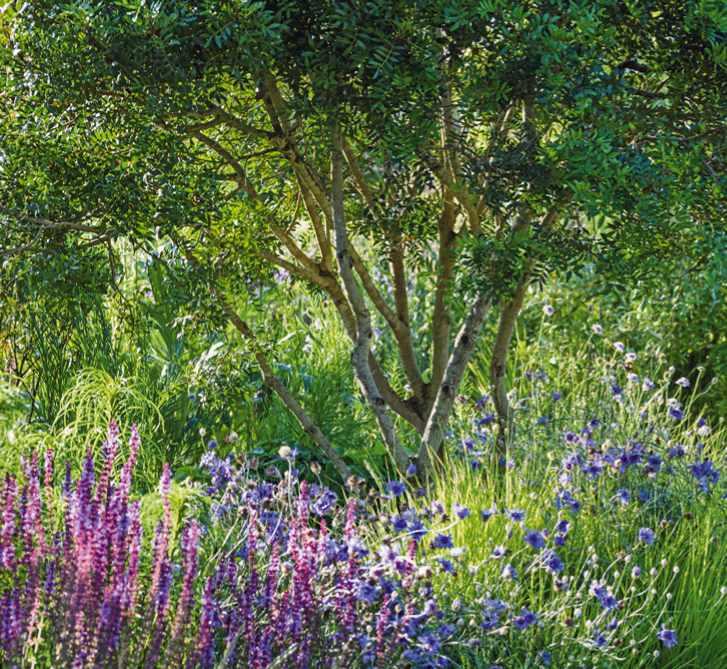

Increase the vertical physical structure in your garden by having as many levels of planting as you can, from high to low. Greater physical diversity increases the number of animals that can find food, nesting sites, and places to roost. A lawn alone, on the other hand, may attract just starlings and wood pigeons. TOP TIP Add some shrubs and you might also get blue tits and house sparrows; taller trees will encourage song thrushes and great tits to make an appearance in your garden.

Feed the locals

Surprising as it seems, the leaves of most non-native plants are inedible to local leafeating insects, unless they are closely related to a native plant; for example, the caterpillars of the spectacular privet hawk moth (above) will feed on both European and Japanese privet, as well as a range of other plants. TOP TIP Strike a healthy balance between exotic, non-native plants and the wild, native species that often spontaneously pop up, self-seeded in your garden.

Give them succulent treats

In containers, use hardy succulents such as sedums: they’re easy to maintain and create small patches of year-round habitat for insects that can be picked over by winter-foraging birds. They also only require watering during a prolonged drought, and provide pollinators with nectar and pollen when they flower. TOP TIP To maintain interest in the container, plant three or four different types of sedum, including early- and late-flowering varieties, with different growth habits.

Learn to love wasps

Wasps are important pollinators of many plants late in the season, and they eat a lot of common garden pests such as caterpillars and aphids. TOP TIP Throw away your wasp trap – all it does is attract more wasps to the garden. A better way of reducing their annoyancefactor is to cover food and drinks if you’re eating outdoors.

Build a hedgehog highway

Consider how accessible your garden is to animals such as hedgehogs and amphibians – you’d be amazed at how good these animals are at climbing! Hedgehogs can certainly scramble a couple of feet through a dense bush and up over a low wall, while common toads are sometimes encountered in tree hollows and nest boxes some distance off the ground. TOP TIP Leave or create spaces beneath fencing to allow them to pass under, or plant dense hedging close to boundary walls.

Give nature a home this winter

Animals will be in your garden for 12 months of the year, so think about how you can structure your garden to provide food and shelter all year round. For example, evergreens such as holly and common ivy will provide nectar and pollen in their flowers, then edible berries, and – come winter – a cosy refuge from storms. And don’t worry about ivy killing trees; a healthy tree will always grow faster than the ivy. TOP TIP Leave ivy where possible, and watch it support wildlife in your garden.