2 minute read

Gaming’s Dark Futures

Myron explores how our games flirt with the end of the world, and what it says about how we view our relationship with nature, the environment, and its future.

Advertisement

Apocalypses to the left, dystopias to the right; game developers love to ask what if? What if the Cold War heated up? What if the world was overtaken by hordes of robots? What if humans turned our lush, green planet into one huge metropolis? Not the cheeriest subject, but gaming has certainly seen some interesting takes on the End of Times over the years.

Perhaps gaming’s premier post-apocalyptic series is Fallout. Running since 1997, it’s had a rocky few years recently, but its grimy, retro-futurist aesthetic has become iconic. The series takes place centuries after nuclear war has reduced our civilisation to a wasteland populated by hideously mutated creatures and pockets of human survivors. Soundtracked by classic 40s and 50s jazz and haunted by the jaunty ghost of US capitalism (Hi, Vault-Tech), the games feel frozen in time by catastrophe.

Fallout’s satire stays light-hearted, its worlds serving as sprawling playgrounds for the player. The Metro games don’t have time for such frivolity. Until the most recent entry, Metro: Exodus, these games were set in the underground metro systems of Moscow. Based on the novels by Dmitry Glukhovsky, humanity hides underground in militant factions, fending off mutant threats with scarce resources.

Metro 2033 paints a bleak picture of the future - a horrific world devoid of Fallout’s humour. The franchises are two sides of the same coin: both feeding off 20th century anxieties around nuclear war. They each portray a mother nature crippled and contorted by short-sighted human politics, leaving the dregs of humanity to keep fighting amongst themselves.

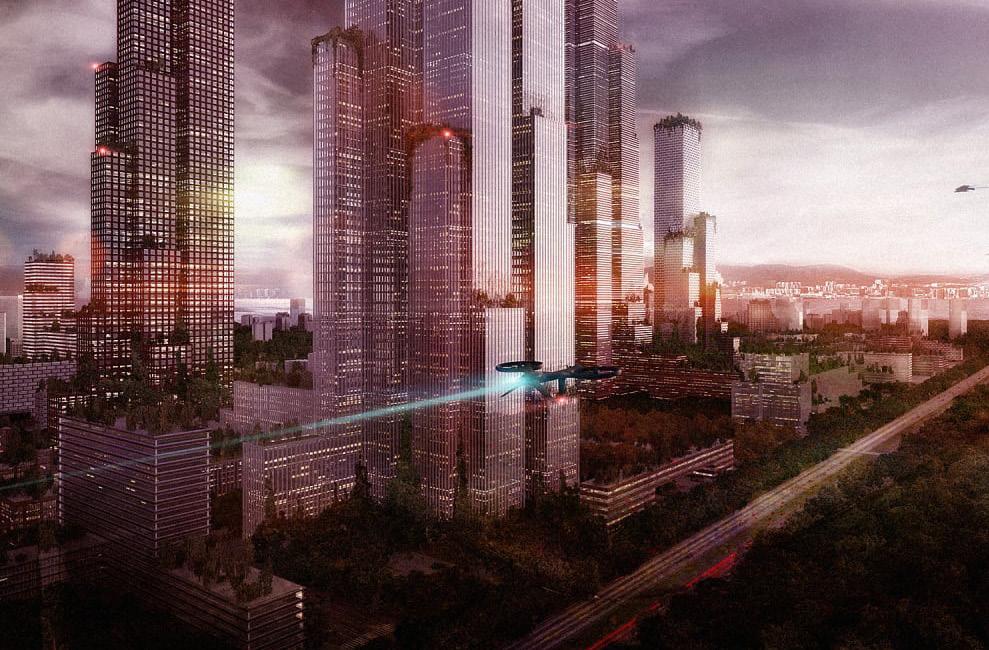

But what if that climate degraded more gradually? The cyberpunk subgenre, spawning in part from science fiction novels of the ‘80s, runs with this idea. The Deus Ex series, started in 2000, then rebooted in 2011, portrays a dystopia grappling with transhumanism.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution sees physical augmentations become widely available in mega-cities across the world, where corporations cripple the working class with the costs of drugs needed alongside them (thanks, big pharma). In Deus Ex, our connection with nature has become so frayed we’re actively rejecting our biological bodies.

Myron Winter-Brownhill 2018’s Detroit: Become Human comes at it from the opposite direction, toying with the development of androids’ sentience, searching for the divide between human and machine in a world where they are essentially a commodified slave-class. Many of us already carry an AI in our pocket, so cyberpunk’s bleak vision of a humanity so utterly disconnected from nature that it relates more to its own technology than the natural world it was once an intimate part of, hits ever closer to home. The whole planet is paved over. Amongst the newest and fastest-developing art forms, the humble video-game is the perfect platform for exploring the future’s potential. Players can immerse themselves in these gloomy worlds unlike in any other medium, while learning thing along the way. Sure, word on the street is we’re already living in a dystopia, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have some fun in another one. “The humble videogame is the perfect platform for exploring the future’s potential” Page Design by Natasha Phang-Lee Images courtesy of gameboss.eu and fastcompany.com