4 minute read

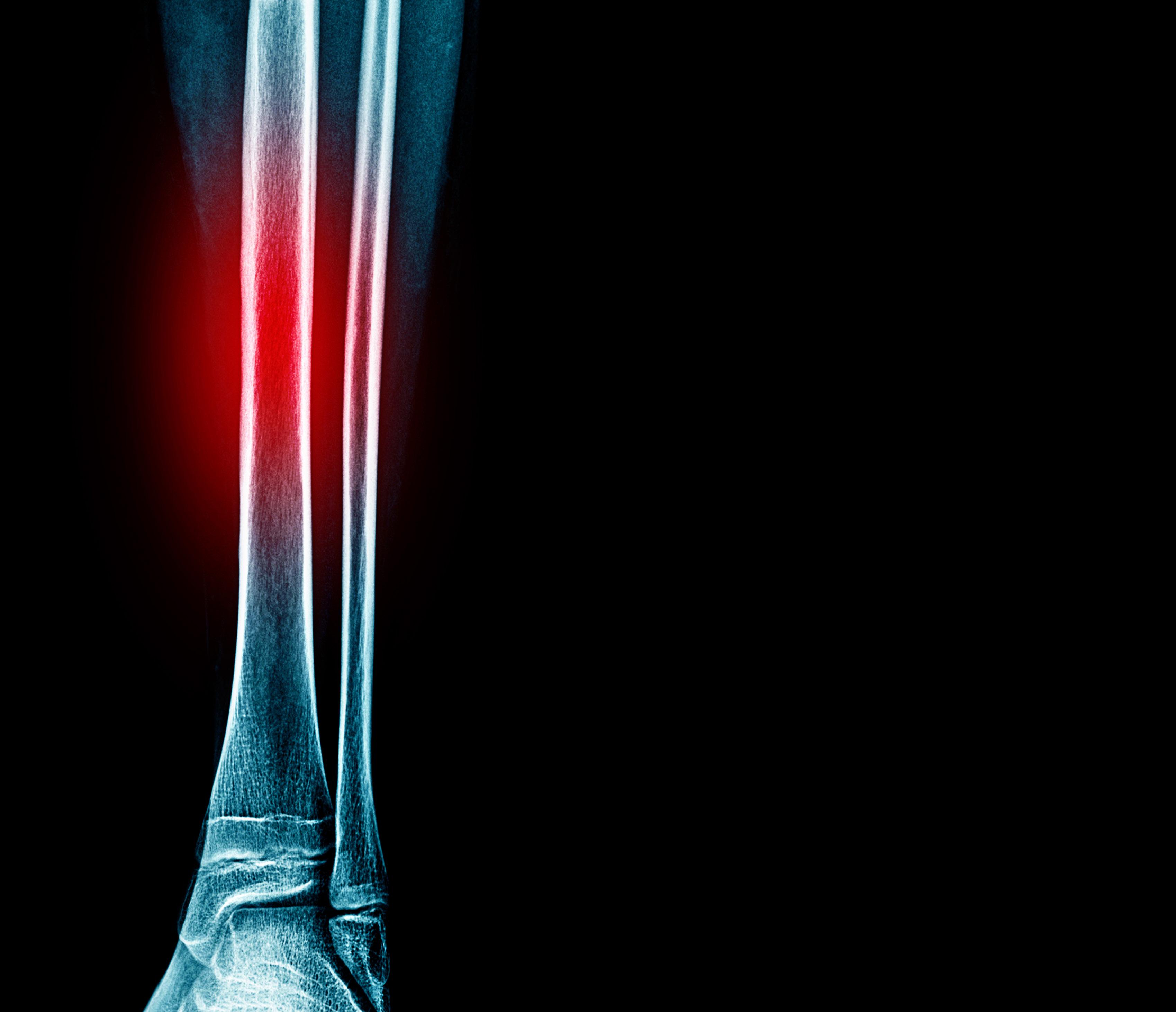

The High-Impact Injury

Stress fractures occur in high-intensity activities, but what actually causes them and how can they be treated successfully?

BY REED FERBER PH.D., CAT(C), ATC A professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology at the University of Calgary, internationally recognized as a leading expert in the research and clinical treatment of lower extremity injuries.

RUNNINGINJURYCLINIC DRFERBER

Stress fractures are one of the five most common running-related injuries and account for six to 14 per cent of all injuries sustained by runners. The bone that is most commonly injured is the tibia (the shin bone) with tibial stress fractures accounting for between 35 and 50 per cent of all stress fractures.

Tibial stress fractures begin as “shin splints” (more correctly called medial tibial stress syndrome), which then progress to stress reactions and finally stress fractures, characterized by fractures to the bone. Shin splints involve overloading to the tibialis posterior (a muscle on the inside of the tibia) and soleus muscles (one of the calf muscles that comprises the Achilles tendon). These muscles control foot pronation and reduce subsequent pronatory and twisting forces experienced by the tibia and foot. Sometimes these muscles are simply weak and loading in the tibia will therefore increase. However, most times these muscles are strong but are overworked since they must compensate for other muscle imbalances. Determining exactly what muscles are weak is critical to prevent stress fractures from occurring.

Many biomechanical factors have also been identified in research literature. Potential biomechanical reasons for developing a stress fracture can be divided into three general categories: impact forces, twisting forces, and pronatory forces. Greater impact forces experienced by the foot and tibia have been measured in runners with tibial stress fractures compared to non-injured runners. Running in the incorrect shoe or in shoes that are worn out have also been shown to significantly increase impact forces. It has also been shown that after rehabilitation from a stress fracture, the amount of impact experienced by runners does not change. Thus, impact forces alone do not explain why a stress fracture develops.

Twisting, or torsional forces, to the tibia can also lead to a stress fracture. If the foot excessively pronates, or collapses inwards, greater pronatory and twisting forces are experienced since foot pronation and tibial rotation are coupled biomechanical motions. However, our research, and research from other labs, has shown that hip muscle weakness is one of the most common sources for increased twisting forces. During the stance phase of gait, the tibia and femur internally rotate, and these motions are primarily controlled by the deep external rotator muscles (the piriformis muscle to name one). In addition to the internal rotation, the knee collapses inwards and this motion is controlled by the hip abductor muscles located on the outside of the hip (the gluteus medius). Weakness in either one of these muscle groups can allow the leg to collapse inwards and increase pronatory and twisting forces experienced by the tibialis posterior and soleus muscles. Despite their proven importance, hip muscle strength is often overlooked as a potential contributor in the cause of a stress fracture or as an integral part of rehabilitation.

Typically, rehabilitation for a lower extremity stress fracture requires six to eight weeks of complete rest to allow the bone to heal. As discussed previously, since stress fractures arise due to several different factors, it is critical to identify each of these factors to optimize your rehabilitation. The general approach discussed here may

not apply to all runners but will focus on those factors that have been identified by researchers as most important.

For the first six weeks, the emphasis is to begin active rehabilitation and start a gradual progression back from non-weight bearing to weight bearing activities. Therefore, rehabilitation should be focused on developing strength from a foot-up and a hip-down perspective, as well as ensuring the runner has footwear specific to their type of foot and foot mechanics.

Once the pain has been resolved, sufficient strength has been gained, and your physician or health care professional has cleared you to start weight-bearing activities, the functional phase of rehabilitation begins. The specific aim of the functional phase is a gradual return to training without reinjury. It is also important that strength continues to improve by completing hip and lower-leg strengthening exercises on a regular basis. It is equally important that a gradual return to activity is implemented. The general recommendation is no more than a 10 per cent increase in training intensity, duration, and/or distance per week, and that adequate rest is given between training sessions (at least 48 hours). This allows for adequate rest and recovery for the structures (muscles, joints, bones) and will help to prevent a reoccurrence of symptoms.

If an increase in symptoms arises once training has been resumed, it is essential that activity again be modified. The intensity and volume of training should be significantly reduced and the substitution of non-weight bearing activity such as deep-water running or stationary biking is recommended. An increase in symptoms represents an incomplete recovery and more time must be spent in the active rehabilitation phase prior to further increases in training. If symptoms persist despite rehabilitation efforts, then a visit to a sports medicine physician or qualified health care professional is recommended for further investigation.