COMFORT IN (/AND) DISCOMFORT

The deliberate integration of discomfort into our routines through design

A THESIS BY ALEX FU

COMFORT IN (/AND) DISCOMFORT

The deliberate integration of discomfort into our routines through design

© Copyright by Yunxi (Alex) Fu 2024 All Rights Reserved

Contact: Alex Fu (Author) - fualex0316@gmail.com

1

UNDERGRADUATE THESIS : ARCHITECTURE

THESIS BY

ALEX FU

THESIS ADVISOR : MEREDITH

SATTLER

AREA OF STUDY : DISCOMFORT IN ARCHITECTURE

PREFACE

Perceived through an anthropocentric lens, humanity has adopted an erroneous perception that comfort is the result of calculated endeavors to remove all discomfort via hyper-efficient production. The lack of regard for non-human entities in the pursuit of the principle of utility is magnified by the ability of civilizations to alter the planet as they see fit, often woefully neglectful of both direct and indirect consequences. As part of the continual effort to bring awareness to the issues of anthropocentric thought, this research and design experiment is a step toward rectifying the tragedy of assuming we are masters of our fate, when, in fact, we are not truly capable of identifying between what we want, what we need, and what we can do without. In our precarious position as creators and beings that possess near-infinite modes of alteration across mediums and time, what keeps humanity in check besides constructs of morality and ethics? We are uniquely positioned to cultivate our behaviors and sensibilities but how can we rely solely on our overly-familiar convictions without constant questioning and skepticism? It is from this avenue of thought that the idea of re-examining our relationship with discomfort stems. Part critique of the antiquated instincts and habits that we possess, part provocation of the contentment we harbor in the presence of modern modes of comfort, this thesis project is inescapably entangled in the instruments of change.

Though not architecturally novel, this project remains flexible and values metrics and merits across a broad set of boundaries and disciplines. The emphasis of this thesis was unclear to me at the beginning, deriving only from the possibility of design to impart change at a systemic scale. We must remain open to challenge and provocation, and expect our preconceived

TIMEFRAME FALL 2023 - SPRING 2024

CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY / SAN LUIS OBISPO

expectations to be unsettled. As such, discomfort is uniquely applicable in this instance because its endurance reveals the shortcomings in the sureties of comfort. Compared to the extremity of pain, chronic illness, and suffering, discomfort sits distinctively far from the drama of crisis but everpresently within the dimension of the comfortable.

As David Ellison and Andrew Leach aptly puts it:

“Discomfort occurs at the point where a given arrangement fails: an impacted cushion jabs, a décor jars, a chimney blocks, a hospitable gesture disappoints, a social more slips. Each of these failures registers as a percept; a system disorder translated into a range of physical and emotional responses that manifest discontinuities and points of resistance between environments and their inhabitants, unhousing them to greater or lesser degrees, depending on their source and duration. The resulting change of state- a shift from oblivion to attentiveness- confers and unwonted dynamism on domestic space conventionally reserved for the unremarkable expression and amplification of personal values, tastes, and sexualities.”

(Ellison and Leach 2018, 2)

Experiencing discomfort leads us to be more aware and conscious rather than take our surroundings for granted. The greater the awareness of our environment, the more textured and nuanced our spaces become. The unexpected and disruptive introduces a kind of vitality and purpose to the spaces that we live in. In this critical juncture where we have the means to do almost anything we desire but lack the collective aptitude to know what we should do, architecture and design sit at the precipice of great, controlled change.

3 2

V. SUPPLEMENTARY DESIGN EXPERIMENTS

ABSTRACT SHOW DESIGN RESULTS/ CONSEQUENCES

LAMP, of Pavlovian Origins

LITERATURE

KOWLOON

5 4 ABSTRACT 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 A A A B B A A A A B B C C A A A A B B C C BROADER WORLD

MOTIVATIONS DESIGN OVERVIEW

to the Madness

WALLED CITY, AN INTRODUCTION Comfort-Discomfort Dichotomy Intentions Towards the slightly abnormal Leisure, Carte Blanche A Tale of Two Scales Systemic behavior Methods

City of Darkness Halprin’s

The People Paternalistic

The City Assertive

Dr.

How

Learned to Stop

Love the Discomfort After Hours Part Architecture, Part Organism Nodal Networks Upward/Inward Growth Self-Regulated Our relationship with the environment IMMEDIATE WORLD VIEWS PROCESS VELLUM LAST WORDS LIST OF FIGURES CONTEXT & INVESTIGATIONS IN RELATION TO ARCHITECTURE INTENT INTERVENTION THESIS SHOW ANALYSIS 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 I. INTRODUCTION II. WRITINGS IV. THESIS DESIGN + INTERVENTION

VI. DISCUSSIONS +

VII. REFERENCES III. SITE 8 14 40 74 84 88 26 7 10 16 42 76 86 90 28 16 42 76 30 17 44 30 20 21 46 78 80 36 36 18 32 11 20 46 78 87 91 34 12 22 24 37 38 24 48 48 80 62

RSVP Cycles

Welfare

Affordances

Lebbeus Wood or:

I

Worrying and

CONCLUSIONS

ABSTRACT

In a society bound by conventions, architecture has been reduced to a select set of principles and common practices designed to cater to efficiency-driven values. Codes and regulations in design prove important to satisfying the five human senses and subsequently contribute to a space of leisure and relaxation. An established body of rules and regulations limits the potential of architecture and design which brings into question the authority and pervasiveness of precedent.

The polarization of the uncomfortable and the comfortable within our daily lives conditions us to favor dormancy over continuous improvement. Thus, when the normality of architecture disillusions its inhabitants into accepting the built environment only as a shelter and place of refuge, we lose the opportunity to think of design as a catalyst.

A typological re-evaluation dissects the existing design paradigms and reimagines buildings as maternal characters capable of nurturing inhabitants and adapting to changes. Seeking to create a rational and functional framework that introduces discomfort into our routines, this thesis could help build long-term resiliency, and foster a continual desire to improve and question the existing. Within the cultural fabric at the

urban scale and the human scale, this approach takes influence from Kowloon Walled City and its lessons of adaptability in a less-than-optimal environment to strategically leverage discomfort alongside comfort. This approach stems from a critique of the lack of affordances in design and our over-reliance on comfort. Shaping how we view discomfort and discovering ways it can help design have a more pivotal influence on how we behave, architecture fulfills a more balanced and whole purpose. This thesis will therefore demonstrate methods for realizing a nondichotomous space that recognizes the nuances of human nature and reframes discomfort as an integral characteristic of the human experience. Discomfort leads to avenues of innovation, creativity, and the forming of deeper connections between individuals and their surroundings. Purposefully and strategically integrating discomfort into our leisure-dominant lifestyles disrupts the dichotomy of comfort and discomfort which forces us to simultaneously experience the desired and undesired feelings and emotions, fostering a well-rounded and complete experience with our surroundings.

7 6

A-01 (Above) Photo of French designer Benoit Malta’s deliberately inconvenient chair. This chair requires balancing and introduces the idea of “bearable discomfort.” Malta tried to modify human habits through the engagement of the body.

9 8 I INTRODUCTION 1 BROADER WORLD IMMEDIATE WORLD IN RELATION TO ARCHITECTURE 2 3 10 11 12

I . 1 . BROADER WORLD

The celebration and consistent yearning for comfort in our daily lives is rooted in the cultural definition of success. What does it mean to be successful in the modern age? For many, success invokes images of wealth and struggle-free leisure devoid of any inconvenience. Legendary U.C.L.A. basketball coach John Wooden personally defined success as “peace of mind attained only through self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do the best of which you are capable 1 .” Definitions of success vary and reflect personal values and priorities. Thus there exists the notion that success itself can function as an invisible personal compass that influences how we lead our lives. A study by Populace and Gallup looked into how people defined success plus its relation to well-being and found that more than 80% of Americans believe they are achieving success “according to their own view of success, rather than what they believe to be society’s view of success.” Hence, the assumption that society largely views well-being as a result of achievement and accomplishment is incomplete but not necessarily wrong 2 Most Americans view quality, interpersonal relationships as vital to their personal view of success. Meanwhile, they assume that the consensus for success in society revolves around status-oriented characteristics. The implication here – at socio-economic and policy levels – is that systems that offer the greatest variety of opportunities for individuals to achieve and fulfill their own personal view of success should be invested in moving forward.

The emphasis placed on the variables that contribute to a successful life stewards humanity towards empowerment via introspection and achievement of personal goals, but the perceived societal consensus for the definition of success is still based on status. As such, understanding comfort and discomfort in contemporary life is invaluable to achieving true well-being.

The reality is that conventional assumptions about success dictate a large facet of modern life. In pursuit of status and recognition, a dance of commutes and routines reveals the societal reliance on comfort to escape the exhaustion and turmoils of the workday. Meanwhile, the rigid and banal orthodoxy in work-life design dogma leaves little room for the infinite complexities of modern life and personal views of success. The wants of the modern individual are often naively understood to be categorical, when in reality, the ambiguities and nuances of the human experience offer unique and novel obligations towards design, obligations that are seldom prioritized against the validity of prevailing precedent and architectural thought of the past 3. The polarization of uncomfortable and comfortable within our daily lives can condition us to favor dormancy over continuous improvement and the built environment – along with antiquated preconceived notions - is systemically responsible.

Our relationship with our environment is in a constant state of flux, with our idea of wellbeing shifting across different cultures and epochs. Modern society depicts discomfort as a looming threat to our comfort, an entitlement appreciated as the result of rigorous effort. Dressed under the guise that comfort is the fruit of our (and our ancestor’s) labor, domestic space-making is decidedly reduced to a cloistered refuge, disregarding the more experimental approaches to alternate types of space that may be perceived as uncomfortable. Discomfort is an invitation to change and evolve.

Discomfort has historically been a catalyst for architectural innovation. Modernist architecture and its minimalism surfaced as a reaction against the excessive ornamentation of previous styles. Modernism reduced design to the essentials and provoked a more responsive engagement with space. Similarly the Bauhaus movement, with its emphasis on functionality and simplicity, produced spaces that were initially perceived as inhospitable. The discomfort that stems from uncommon design practices encouraged designers to think differently about space and reevaluate function and form 4

As Ellison and Leach write in On Discomfort the endurance of discomfort reveals the “points of resistance between environments and their

inhabitants,” and brings an unwonted dynamism to space-making. These are opportunities that can radically alter the interactions between man and building.

Instinctually, it is practical to avoid the frictions and conflicts of life, but there is value in discomfort’s capability to compel the expression of often-neglected unpleasant feelings. Discomfort, often understood to be the negation of comfort, can instead be complementary. While comfort immobilizes us physically and mentally, palpable distress invites us toward inspired action 5 Though viscerally unpleasant, leaving the comfort zones catered to by modern life is important to both recognizing and dealing with the fear of discomfort. The potential for significant personal breakthroughs and transformations inhabits the realm outside the comfort zone. By gradually and intentionally distancing oneself from comfort, “productive discomfort” can be achieved and leveraged, which grants the capability to thrive in the face of unfamiliar situations, tackle unpleasant ideas, and learn new skills to take on complex problems 6 Applicable in academic, work, personal, and recreational settings, productive discomfort is essential to achieve the unexpected. Embracing uncertainty fosters innovation and adaptability, which produces a more robust and resilient collective well-being.

In social contexts, discomfort can be a powerful tool that promotes social interaction and builds relationships in a community. Public spaces that challenge users through surprise and mild discomfort encourage people to engage more actively with the surrounding intervention. While interactive elements are widely found in design in both urban and architectural contexts, complementarily introducing discomfort to this dimension creates the opportunity to bring a community to a heightened state of awareness 7 When tasked with balancing the needs of a community, designers need to account for places of gathering, interaction, and participation. Who, then, is responsible for challenging the masses? Social design with discomfort strategically implemented can facilitate well-rounded well-being. Overall, this application is a much more efficient and nuanced use of design.

11 10

I . 2 . IMMEDIATE WORLD I I2 1-INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION

1. John Wooden, “The Difference Between Winning and Succeeding,” (TED, 2001)

2. The disconnect alters the perception of what success means. We should value the personal view of success but the societal view still heavily affects our goals and priorities.

3. Valerio Olgiati and Markus Breitschmid, “Non-Referential Architecture” (Germany, Park Books, 2019)

4. Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus, 1919-1933 (Germany, Taschen, 2006)

5. J. Pezeu-Massabuau, A Philosophy of Discomfort (University of Minnesota Press, 2010)

6. Vaughn Tan, The Uncertainty Mindset (Columbia University Press, 2020)

7. Jan Gehl, Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987)

B-01 (Above) A pie graph showing the composition of success, by domain percentages from Populace/ Gallup’s study on Success Index.

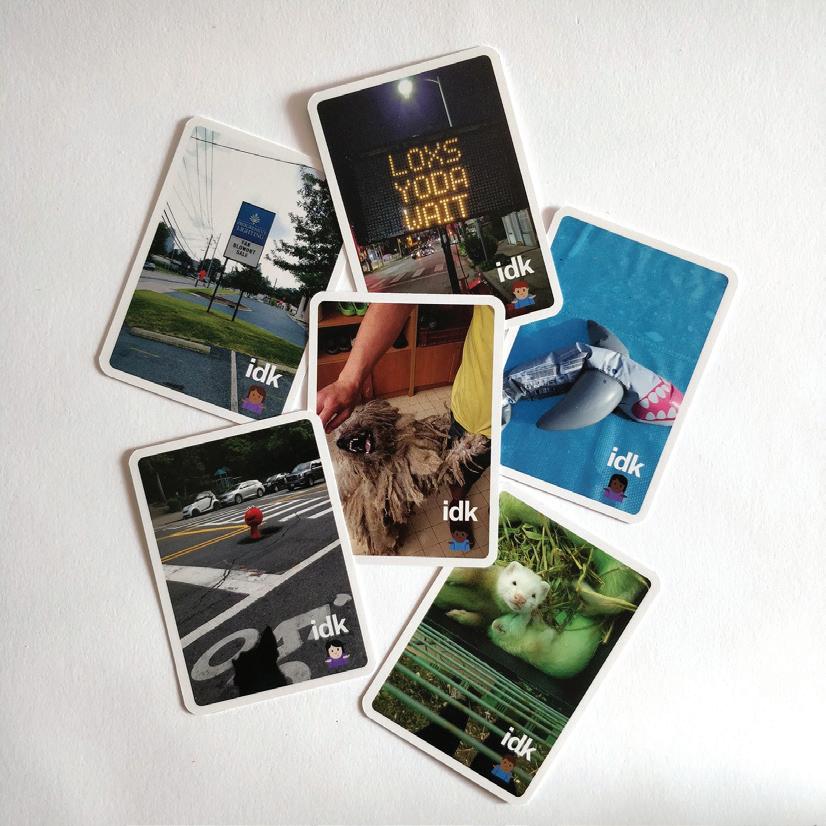

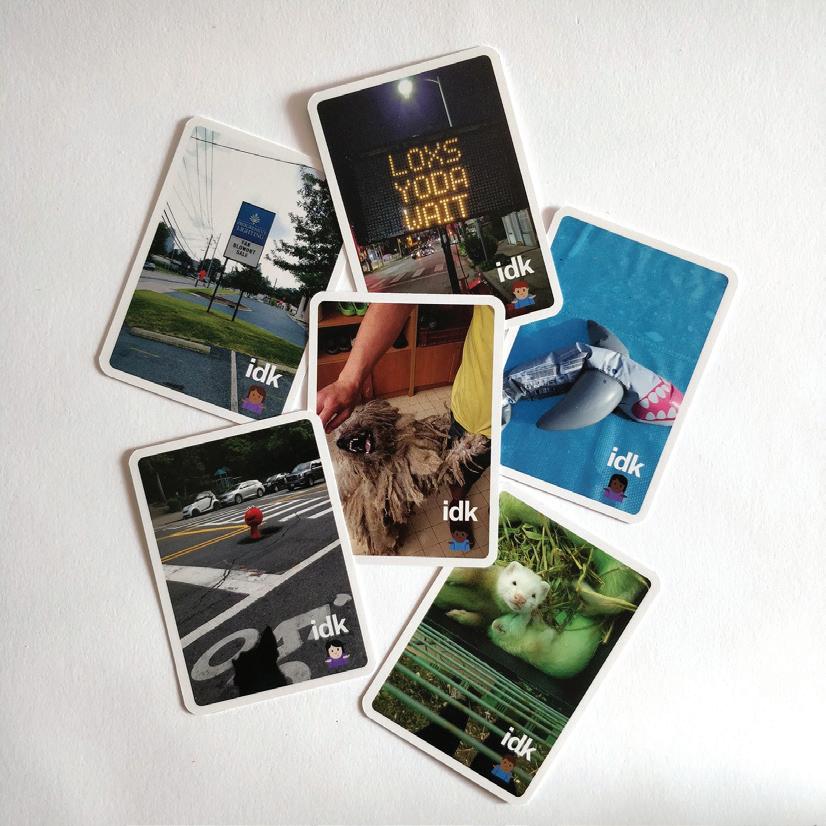

B-02 (Above) idk, a collection of cards that suggests something players can do to be intentionally and producitvely uncomfortable, designed to help players grow and learn.

I . 3 . IN RELATION TO ARCHITECTURE

Spaces that produce stabilized states of equilibrium welcome unyielding passivity. Accordingly, spaces that invoke a consistent demand of inhabitants’ attention and effort are likely to produce an ephemeral glimpse into true wellbeing. In lieu of a provocative effort that recognizes the inevitability of disequilibrium, an architecture of tranquility would only displace discomfort temporarily while contributing to a problematic dichotomy. To wholly villainize discomfort is to neglect an entire facet of the human experience. Discomfort is ubiquitously experienced without exception, lending itself to being a necessary and uniquely qualified design driver.

Consigning space to challenge preconceived notions of cognitive, physical, and organizational ergonomics can contribute to the depolarization of comfort and discomfort, both in the workplace and domestically. Weaving together designs that were previously separated by their facilitation of either work or life, puts forth novel hybridized programs where existing conventions of comfort vs. discomfort are challenged. This engagement of architecture and the realm of the uncomfortable derives itself from the manipulation and repurposing of architectural elements, the enduring of which more accurately portrays the trials and tribulations of modern life. The resulting architecture is a liminal space in which the experience of the uncomfortable is celebrated and exploited alongside the comfortable

When strategically and purposefully utilized, discomfort can prove useful in eliciting psychological and physiological responses from users of a space. For instance, narrow spaces can induce feelings of unease or even claustrophobia, and deliberately doing so adds to the experience; art installations or memorials can take advantage of this powerful tool to make their space more memorable and effective 8. The use of stark and cold materials or the design of disorienting spaces creates a contemplative and emotional atmosphere, allowing designers to call attention to a specific

entity, event, or history. On a more physical note, discomfort can incite physical movement, or limit it, altering the traditional functions of the environment. In certain environments, the notion of fast or slow movement can be designed for and encouraged. Designers can prevent or encourage loitering, follow a specific route, and gather in a central space, essentially choreographing the movement of users through space 9

We often take our surroundings for granted, oblivious to instances of design or areas where safety is a concern. Strategies like uneven floors or variations in texture can help users become more aware of their surroundings. There is also the method of using unconventional forms and materials to encourage users to reevaluate the aesthetics and function of spaces. Beyond the mere sensory experience, this adds to the language and poetics of space imparting deeper meaning in spaces usually treated as blank canvases 10 The ability to raise awareness and encourage deeper engagement with our surroundings makes discomfort an invaluable instrument of design. On an individual level, psychological discomfort can lead to introspection and self-awareness. Leveraging spaces designed for solitude or contemplation, architecture can begin to focus users’ minds inward. Reflective surfaces can possibly challenge users to reflect on their own identity 11

With a variety of purposes, discomfort strategically employed in architecture shapes the human experience beyond mere surface-level functionality. Sensitivity to not only our surroundings but also one’s presence in an environment is the first step to an architecture of awareness. These strategies highlight the profound impact of design to shape human emotions and behaviors. Discomfort ultimately provides insight into the human condition, which is increasingly characterized by discontinuity and heterogeneity.

13 12

I3INTRODUCTION

B-03 (Right) LOOK HERE installation by Suchi Reddy; fractals made with reflective panels creates a contemplative space (Photograph by Chris Coe)

8. K.C. & Moore Bloomer, Body, Memory, and Architecture (Yale University Press, 1977).

9. W.H. Whyte, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (Project for Public Spaces Inc., 1980)

10. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Reed Businesss Information, Inc., 1994)

11.

J.E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (Yale University Press, 1993)

15 14 II WRITINGS 1 MOTIVATIONS VIEWS INTENTIONS 2 3 16 20 24

II . 1 . MOTIVATIONS

The paradox of comfort hides in the fact that we must define comfort while prioritizing it. Comfort is unstable, varying between each individual nervous system. A gentleman once said, ‘As a furniture designer, I rarely sit; discomfort is terribly motivating.’ It was his method to inspire desire, it made him care.

Nanu Al-Hamad

LEISURE, CARTE BLANCHE

Though not inherently bad, leisure can have potentially negative consequences. In contemporary societies, leisure can be detrimental to personal and professional goals when pursued excessively or irresponsibly. In reference to escapism, leisure is often used to rejuvenate and recover from the adversities that inhabit daily life. Driven primarily by the comfort/discomfort dichotomy, leisure can be sought without consideration for other areas of life, undermining the balance that is necessary for true wellbeing. Due to the lack of meaningful engagement, prolonged exposure to leisure has been linked to depression and anxiety 15 Physically, sedentary leisurely activities have been linked to obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes 16

prioritize excessive leisure may face hedonistic challenges and become victims of stagnation. Social rigidity has been cited to cause the decline of nations 18 Though out of the purview of this thesis, economic growth remains an important consideration to a community’s collective wellbeing.

The implication of villainzing discomfort may, at first, sound trivial, but neglecting an entire facet of the human psychology can result in a population that is unwilling to confront undesirable feelings and tasks and ultimately hinders personal growth. Instead of constructively addressing issues, the alluring distraction of excessive leisure prevents individuals from realizing there may be a problem to begin with. In the long run, the issue may become cyclic and hard to absolve. While leisure is important for relaxation and recovery, the lack of balance between productive work and leisure can lead to a purposeless and unfulfilled life, and as previously discussed, personal achievements are crucial for individual ideas of success/achievement (Haidt, 2006). The main takeaway here is the need for a balanced approach to the many facets of contemporary life. COMFORT-DISCOMFORT DICHOTOMY

Individuals encounter many experiences in various aspects of life. This thesis seeks to examine the dichotomy of comfort and discomfort, its complex and dynamic interplay, and its role in shaping our behavior relative to the design field. While comfort provides the instinctually desired sense of stability and security, discomfort can be an opportunity for growth and change. Balancing these two states is crucial when navigating the nuances of well-being.

While it may seem controversial to include discomfort in the design world, navigating uncertainty is a necessary proponent of life. We cannot simply assume the black-and-white nature of comfort and discomfort, especially given the gray nature of reality. The dichotomy is most concerning when it manifests as escapism a form of mental diversion from the unpleasant aspects of life through often unhealthy avenues. The Oxford English Dictionary defines escapism as “the tendency to seek, or the practice of seeking, a distraction from what normally has to be endured”. Often carrying a negative connotation, escapism can turn normal parts of a healthy existence into vices used to detach oneself from reality. This visceral disconnect can remove meaning from many aspects of daily life and lead to a general unwillingness 12 In most instances, escapism is not harmful, but the existence of the comfort/discomfort dichotomy reinforces the binary understanding of what is good and what is bad

To introduce discomfort as a design driver is not intentionally bringing unwanted suffering in the name of novelty. Instead, it is an experimental method that examines the destigmatization of discomfort and intentionality in human behavior. Take, for example, rehabilitation. Subjecting an

individual to physical or emotional turmoil can often result in the restoration of one’s health and well-being. Consider also the alarmist reactions humanity harbored for new technologies that now inhabit the very fabric of society. On one side of the argument is Alain de Bottom’s The Architecture of Happiness which explores how beautiful, welldesigned environments can enhance our happiness. This thesis considers the power of the opposite and highlights the importance of considering both comfort and discomfort in design 13 In ergonomic design, slight discomfort prompts users to correct their posture, reducing injury in the long run.

Once dismantled, the dichotomy of comfort and discomfort becomes a spectrum that affords new ways design can alter human behavior. Everyday objects can elicit emotional responses, and evoking strong emotional connections with the design around us drives engagement and empowers intellect 14 In The Power of Moments , the Heath brothers identify the four components of a memorable moment: elevation, insight, pride, and connection. Elements that challenge and elevate users cannot be neglected. Leveraging discomfort alongside comfort in architecture reflects a broader emphasis on creating impactful experiences within the built environment. The complex interplay between comfort and discomfort offers theoretical and practical insights that form the foundation of designing with nuance and intention. When design is limited to meeting functional needs, the capability to inspire, provoke, and empower is lost.

Another issue arises when leisure is engaged with at the expense of social interactions. With the rise of digital entertainment, it is easy to pursue fulfillment from leisure in solitary. The sense of belonging that one can receive from maintaining meaningful connections with friends, families, peers, neighbors, and co-workers is victimized by the indulgence in solitary leisure 17 It is important that design helps facilitate meaningful social engagement. On a large scale, leisure may also affect economic productivity. Societies that

C-01 (Above) DISCRETIONARY TIME AND SUBJECTIVE WELLBEING; From the study Having Too Little or Too Much Time Is Linked to Lower Subjective Well-Being in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Personality Processes and Individual Differences

17.

18.

17 16

II II2 1-MOTIVATIONS MOTIVATIONS

12. John D. Lee, Chistopher D. Wickens, Yili Liu, and Linda Ng Boyle, Designing for People: An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering (CreateSpace, 2017)

13. While de Bottom critiques “poor design” as a negative contributor to our mood, he agrees discomfort in design (stark modernist design for example) can contribute to a deeper appreciation of our built environment.

14. Daniel Miller, The Comfort of Things (Polity, 2009)

15. Cal Newport, Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (Portfolio, 2019)

16. William D. McArdle, Frank and Victor Katch, Exercise Physiology: Nutrition, Energy, and Human Performance (LWW, 2014)

Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Touchstone Books/ Simon & Schuster, 2001)

Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities (Yale University Press, 1984)

OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ENVIRONMENT

The environmental degradation caused by anthropocentric perspectives has been deemed irreversible by the scientific communities. The general public is only beginning to see the consequences of environmental neglect, but competing against capitalistic tendencies is a futile endeavour. Understanding human involvement in transforming the planet is one of the first steps to achieving sustainable architectural practices, but a problem as large in magnitude as environmental damage requires a solution of equal magnitude. While design directly impacts our environment through built structures, it can also begin to indirectly reverse our anthropocentric behaviors 19 by bringing awareness to our environmental footprint . Sensory interventions with varying levels of comfort and discomfort can deepen our engagement with our surroundings and thus bring the problem into the front of our consciousness by highlighting our overly human-centric perspectives 20

Consideration for the environment begins by realizing our practices have wide-reaching consequences. Beyond mindfulness and awareness of our actions, challenging individuals to adapt to varying conditions mirrors the adaptability necessary to address the challenges posed by human-induced climate change. How might design shape our routines to challenge conventional notions of comfort? Which routines are unsustainable and how can design encourage eco-friendly behaviors? Because architecture dictates much of our routine behaviors, it is uniquely qualified to lead the response to the rapid environmental changes driven by human activity. Through passive design strategies and environmentally sensitive use of materials, design has already begun to mitigate our footprint, but it is not nearly enough. While

passive strategies may begin to lessen our energy use, d esign needs to guide (or perhaps force) the collective behavioral change where users think first about the environment and themselves second 21 For instance, limiting the use of climate control systems may be initially uncomfortable and, in some climates, borderline radical. However, when the surrounding architecture constantly reminds users of the error in their behaviors through slight discomfort, the population might think twice before turning on the air conditioning. Architecture should encourage better habits and the adaptation of mindful practices.

Human health and well-being are inescapably interconnected with the environment. Most of society still does not understand how neglecting the environment will harm the future, so when it is not reinforced along every stop in our routines, it is woefully easy to prioritize our comfort above the health of the environment and other creatures that inhabit it. One of the goals of this thesis is to use discomfort to highlight our role in the Anthropocene so society begins to truly reconsider its relationship with the environment. The built environment should actively attempt to align our values with those of the environment. Similar to hostile architecture’s ability to prevent action or use, design carries the burden of enabling systematic change. While this enormous undertaking is beyond what a single thesis can achieve, this thesis must add to the discussion and begin to establish a framework that can be widely applied.

which are not visible to visitors. Despite the greenwashing, this project still serves as an iconic landmark that calls attention to the importance of sustainable strategies. It will continue to remind visitors and inhabitants of the environment. Projects like One Central Parks show designers

to sustainable practices.

19 18 II II1 1-MOTIVATIONS MOTIVATIONS

19. Erle C. Ellis, Anthropocene: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2018)

20. Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2012) 21. Ian L. McHarg, Design with Nature (Wiley, 1995)

C-02 (Above) One Central Park by Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Though the plant facade is arguably greenwashing, this project showcases 250 species of Australian flowers and plants and looks widely different from the surrounding buildings. Still, roughly 50% of the facade area is covered in a vertical landscape designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc. Besides the plants acting as sun control, there are also other sustainable strategies hidden in the building’s infrastructural systems,

ways to bring awareness

II . 2 . VIEWS

Design is multi-disciplinary and spans many scales. Through a systems frame of mind, architecture can reach a wider audience. Better yet, designers who learn and adopt new strategies are contributing to a collective framework that builds off the precedents and conventionally established principles of the past. This makes architecture a fitting tool to affect the behaviors and routines of communities across the globe. Traditionally, architects sought to provide shelter and comfort to inhabitants and, in contemporary times, cater to modern lifestyles. Generally, innovation in design serves to solve existing problems, but this passive mode of design does not utilize architecture to its full potential. A proactive mode of design would, at the very least, support human growth and evolution.

By prioritizing a community’s education, productivity, social interaction, adaptability, and sustainability, designers allow room for growth. Spaces that are flexible and conducive to learning help communities thrive. By adopting the responsibility of the community’s growth, designers are tasked with considering clients’ past, present, and future. The expansion of scope allows designers to effectively look after a client’s cognitive and emotional well-being, well past the end of the design process. Treating architecture as a system profoundly increases its impact and effectiveness.

Systemic architecture is widely applicable, spanning personal and social scopes. In the academic setting, designers can prioritize learning and creativity. In place of simply integrating technology and utilizing the open concept,

supporting the diversity of learning methods and encouraging student engagement via interactive design is much more inclusive and effective 22 Expanding the scope of the design to include more than physical interventions allows for the opportunity to impact education on a psychological level as well.

Systems architecture in the workplace has manifested as activity-based working (ABW) and essentially promotes offering a variety of work settings. For example, the workplace is zoned into quiet, collaborative, and recreational spaces 23 While this begins to dismantle the comfort/discomfort dichotomy, designing for employee well-being requires consideration of employee routines and not only their performance.

Well-designed public spaces where people can gather, socialize, and engage in communal activities lead to vibrant and resilient communities 24 . Systemic architecture would attempt to alter the routines of the public. Dynamic urban environments need to account for public well-being. The typological park or greenspace merely allocates space for the public, but civic engagement is crucial for helping the community evolve. Cultural and aesthetic stimulation is one way to inspire creativity and encourage the public to innovate and think outside the box. Art in designed spaces can profoundly influence our emotional and intellectual growth. By asking what else can help the client, designers can systematically help support behavioral growth.

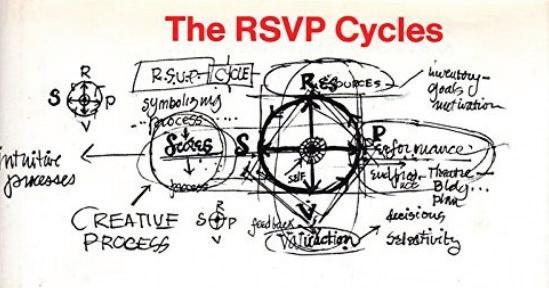

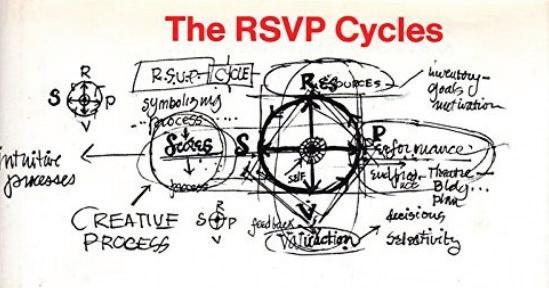

Introduced by Lawrence Halprin in his book The RSVP Cycles: Creative Processes in the Human Environment, the RSVP Cycles systematically contributes to human growth. RSVP represents [R]esources, [S]cores, [V]aluaction, and [P]erformance. Together they represent an approach to design and planning that revolves around choreographing the movements and behaviors of people.

Resources

This phase involves comprehensively gathering and assessing all available resources, which can include people, environmental factors, skills, knowledge, and materials. The assessment provides insights into how individuals and communities can maximize their potential. It also allows for a holistic understanding of all available resources which makes optimizing for efficiency possible.

Scores

After the assessment of resources, scores guide the use of these resources. They are plans, notably compared to musical scores that provide structure, but the framework itself is open to interpretation and flexibility. Striking a balance between flexibility and structure encourages adaptive thinking, helping communities build resiliency. Subsequently, responding to changes and challenges will be like second nature and foster innovation.

Valuaction

This phase evaluates and reassesses the processes and outcomes of the previous two phases. In the

same vein as the flexibility of scores, this phase is emphasized by iterative adjustment based on feedback received from the first two phases. The continual evaluation loop helps individuals or communities learn from prior experiences, adjust accordingly, and achieve improved results. Essentially a framework for evolution, the valuaction phase empirically structures growth.

Performance

The last part of the process is implementing the plans previously set up. Simultaneously, there is the interaction with resources and scores in real-time. The performance phase is responsible for experimenting in reality. Any insights from the previous phases will further refine the entire process. In the real world, this presents as developing one’s skills and one’s problem solving abilities. Learning through experience is fundamental to adaptability.

Communities can heavily benefit from the iterative nature of the RSVP Cycles. Making adjustments in real-time and constantly reinterpreting encourages individuals and communities to experiment beyond risk thresholds to reach novel solutions. Being prepared for feedback and changing circumstances counter any effects uncertainty might present. The inclusion of such a diverse set of resources promotes collaborative efforts and places responsibility for growth on the collective, which also benefits from increased social cohesion. Perhaps the most useful to communal growth is the reinforcement of continual learning. The act of reflecting, learning from both successes and failures and then using this experience for future endeavors inextricably integrates continuous learning into the daily routine. Halprin’s robust framework helps architecture maintain impermanence and continue to evolve post-occupancy. Observing and analyzing how users engage with the design interventions will help designers understand its effectiveness and where it can improve. The application of the RSVP cycles allows designers to create dynamic and responsive environments, and as previously noted, design no longer caters only to the past and present, but also to the future. As the needs and desires of society change over time, so too will the built environment, continuously supporting human growth.

21 20

II2VIEWS

II2VIEWS SYSTEMIC BEHAVIOR

HALPRIN’S R.S.V.P. CYCLES

22. OWP/P Cannon Design, VS Furniture, and Bruce Mau Design, The Third Teacher: 79 Ways You Can Use Design to Transform Teaching & Learning (Abrams Books, 2010)

23. CBRE, The Complete Guide to Activity Based Working (Hanna, 2021), referencing specifically the Google Head Quarters

24. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Vintage, 1992)

C-03 (Above) Ordos Smart Sports Park by PLAT Asial; Incorporating various interactive elements for children and a semi-open corridor encourages interaction among visitors of all ages. The dynamic atmosphere is created by planned instances of engagement.

C-04 (Above) Halprin’s Illustration of the RSVP Cycle in effect.

PATERNALISTIC WELFARE

Referring to the welfare policy where a governing body makes decisions on behalf of individuals, paternalistic welfare will limit the autonomy and personal freedom of an individual under the rationale that the governing body is in the position to make the best/right choice. Ultimately, the intent is to promote overall well-being. The belief is that certain individuals may make decisions that will negatively affect their health or safety. One key characteristic of paternalistic welfare is the involvement of restrictions and interventions to positively influence behavior 25. Some criticize the infringement on individual autonomy, the possibility of governing bodies overreaching, and the uncertainty in making the most informed decision. Yet it remains a legitimate approach to well-being. There are instances where individuals may lack the knowledge or capability to make an informed decision. Seatbelts and helmet mandates protect individuals from accidents. Mandatory vaccinations protect individuals from harmful illnesses. In reality, paternalistic policies can significantly improve a community’s public health, safety, and well-being. The glaring caveat is the difficulty in correctly determining when and how to help an individual. Through the lens of paternalistic welfare, the intentional use of discomfort gains validity.

When arguing in defense of coercive paternalism, Conly cites cognitive biases and irrational decision-making. Similarly, autonomous individuals frequently make poor choices due to inadequate information, self-control, or foresight. Despite free will being an instrumental pillar of life, autonomy is not an absolute good. Conly provides empirical evidence from behavioral economics and psychology to demonstrate how often people make decisions detrimental to their own best interests. While intervention from outside sources remains a slippery slope, intentional discomfort merits recognition as a pragmatic approach to improving overall well-being 26 The debate between autonomy and paternalism remains nuanced but coercive paternalism is undeniably justified in some cases.

Designing space in ways that compel individuals to engage in beneficial behavior equivalently resembles coercive paternalism. Using the RSVP cycles and coercive paternalism in a complementary manner, architecture can be designed to maintain the psychological well-being of users. To quell ethical concerns, designers can prioritize transparency and include communities in the process to accurately reflect their ever-changing needs. Here, the balance between personal freedom and intervention must be maintained and sensitively

considered. Like a score, designers are responsible for choreographing the rhythm of autonomy and coercive paternalism. By taking advantage of the adaptability and resilience of an individual, designers can compel specific behaviors, as long as it’s ensured that the benefits outweigh the reduced autonomy.

Cities like New York have encouraged designing architectural features that specifically promotes physical health by implementing Active Design Guidelines. An example is an easily visible and attractive staircase, which compels users to choose the stairs rather than the elevator. Similarly, LEED certifications require designers to meet a strict criteria for energy and utility efficiency. Perhaps most relevant is the WELL Building Standard, which focuses on prioritizing user health and well-being by considering air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, and comfort. WELL certification, like LEED, has a stringent design criteria. Proposals that go beyond policy and certifications begin to step into the territory of nudge theory, which is a concept coined by behavioral economist Richard Thaler.

Nudge theory primarily deals with influencing choices and decision-making, but differs from conventional methods of compliance like education or legislation 27 Nudging is an umbrella term that refers to various techniques and has a robust evidence base, especially for personalized nudging that considers individual differences. Nudging is highly incentivized and predictable, but they are importantly not mandatory. Thaler provides the example of organizing fruit at eye level versus outright banning junk food. A nudge leverages cognitive processes and instincts to produce a desired outcome. Adding to Conly’s defense of coercive paternalism, the discrepancy between an individual’s behavior and their intention makes human slightly irrational beings 28 This value-action discrepancy is explained by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s concept of two separate systems for processing information. System 1 is fast and automatic but susceptible to influences. System 2, while slow, is reflective and accounts for goals and intentions. Time constraints or overly complex situations that overwhelm an individual’s cognitive capacity will often employ system 1, which leads to suboptimal decisions. Habitual behavior is innately resistant to change and requires some sort of catalyst or disruption to override. Nuding techniques take advantage of System 1 decision-making and accordingly alter the environment to a desired outcome 29

23 22 II2VIEWS II2VIEWS

C-05 (Above) Depiction of a fly in a urinal; one of the most cited examples of a nudge. Implemented at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, this nudge intended to “improve aim”. Photo from Getty Creative.

C-06 (Bottom) Babies of the Borough in Greenwich, London. Painted on the shops in Greenwich, depictions of babies reduced crime by 24% in just one year and by nearly 50% after five years. Photo from BBC News.

25. G. Dworkin, Paternalism in Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Standford, 2020).

26. S. Conly, Against Autonomy: Justifying Coercive Paternalism (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

27. R.H. Thaler and C.R. Sustein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Yale University Press, 2008)

28. J.A. Parkinson, K.E. Eccles, and A. Goodman, “Positive impact by design: the Wales centre for behaviour change” in The Journal of Positive Psychology (Taylor & Francis, 2013).

29. Yashar Saghai, “Salvaging the concept of nudge” in The Journal of Medical Ethics (BMJ Journals, 2012)

II . 3 . INTENT

Building upon the broader theory of affordances orginally developed by psychologist James J. Gibson, assertive affordances in designed features, objects, or systems actively encourage engagement in specific behaviors. Crafted specifically to be more forceful than passive strategies, assertively suggestive interventions can be particularly useful in promoting desirable behaviors as well as improving the overall usability of a space. The assertive nature may, at first, overwhelm some and cause discomfort to others, especially when suggestive affordances are far more common. In tandem with the deliberate use of disorientation and uncertainty in designed spaces, assertive affordances promote deep user engagement.

User-friendliness is an antiquated goal since straightforward/ simple interactions and clearly expressed intended uses pacify the user. For instance, marked pathways and barriers that guide pedestrian movement serve to get users from point A to B, often neglecting the journey itself. Designs that provide immediate satisfaction or ease of use prevents the act of discovery. As per the RSVP Cycles, iterative attempts are highly beneficial to growth. Assertive affordances combined with built-in ambiguity address the criticism of reduced autonomy. When carefully and sparingly integrated, assertive measures does not dominate the design space; instead it operates in conjunction with designs that traditionally cater to comfort. To complement this integrated mode of intervention, choice is transparently expressed, ensuring that users can choose to stop participating should the experiment ever become oppressive. If the environment initially seems restrictive or unflexible, clues may be given to provide users with a glimpse of the intended effect.

Actively guiding user behavior can play a significant role in enhancing the poetics of a space. Users stand to benefit emotionally, experientially, and symbolically when they are guided to address uncomfortable feelings. Assertive affordances imbue a space with deeper meaning and resonance when thoughtfully integrated into architectural design. Spaces become profoundly emotional and experiential when their intuitions, preconceived notions, and ideas of comfort are challenged. Ultimately, the use of assertive affordances enriches the overall human experience and only asks users to embrace vulerability and remain open-minded. The process is not unlike psychotheraphy and, through the use of a variety of strategies, aims to treat mental-health illnesses. As long as users agree to inhabit the intervention in a collaborative manner, they will reap the benefits of pushing past comfort zones.

Overlooking controlled discomfort as a design driver capable of providing benefits is tantamount to designing only for function. The consideration for discomfort as part of a cyclic system brings opportunities for innovation, creativity, and meaningful experiences with one another and with the architecture itself. When we take the comfort of routine life for granted, we miss the opportunity to be aware of the design around us. By deliberately integrating discomfort within our leisure and comfort-driven lives, it challenges our existing routines and promotes an awareness that the environment around us is more than inanimate walls, floors, and ceilings

25 24

II3INTENT

II3INTENT

ASSERTIVE

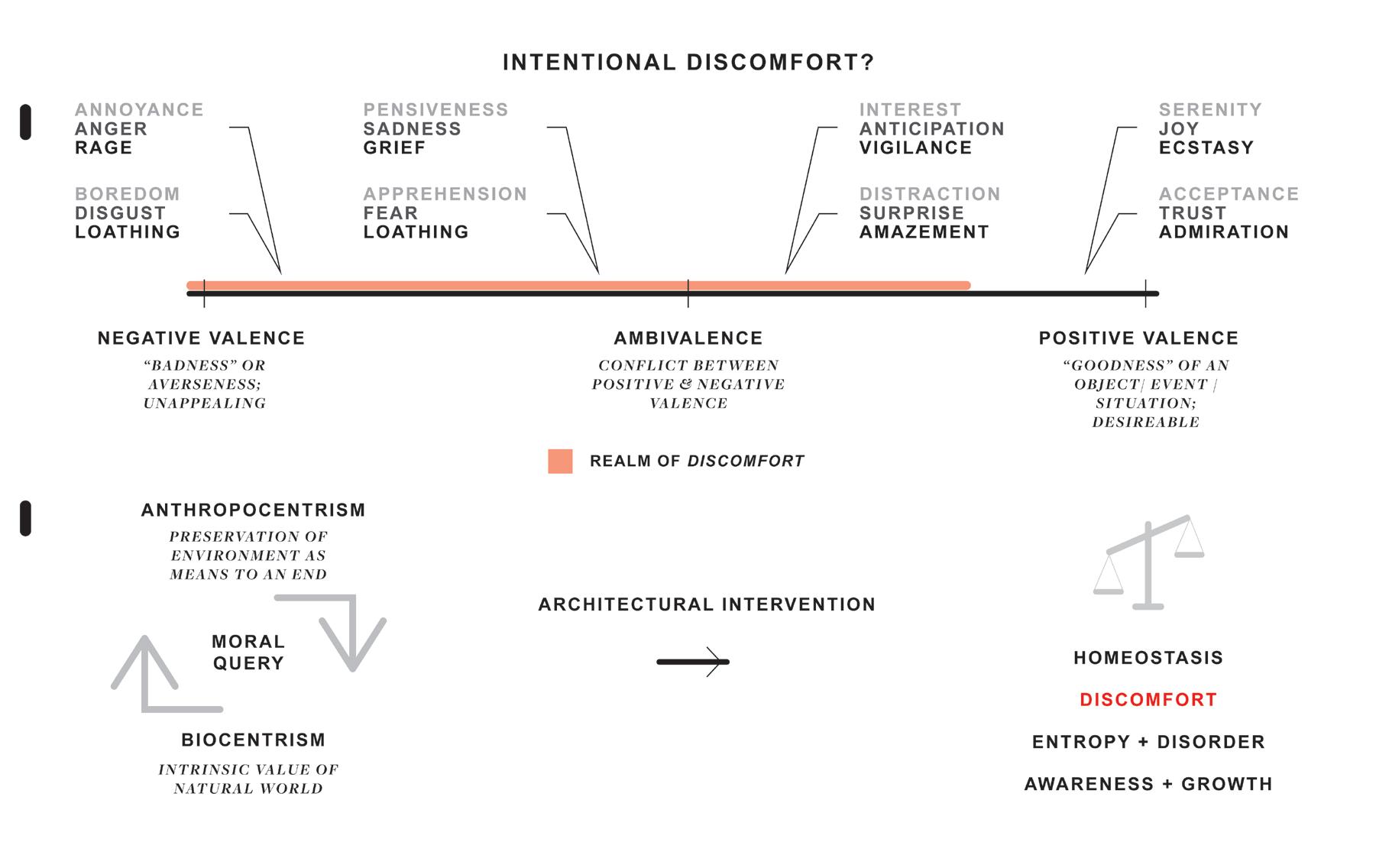

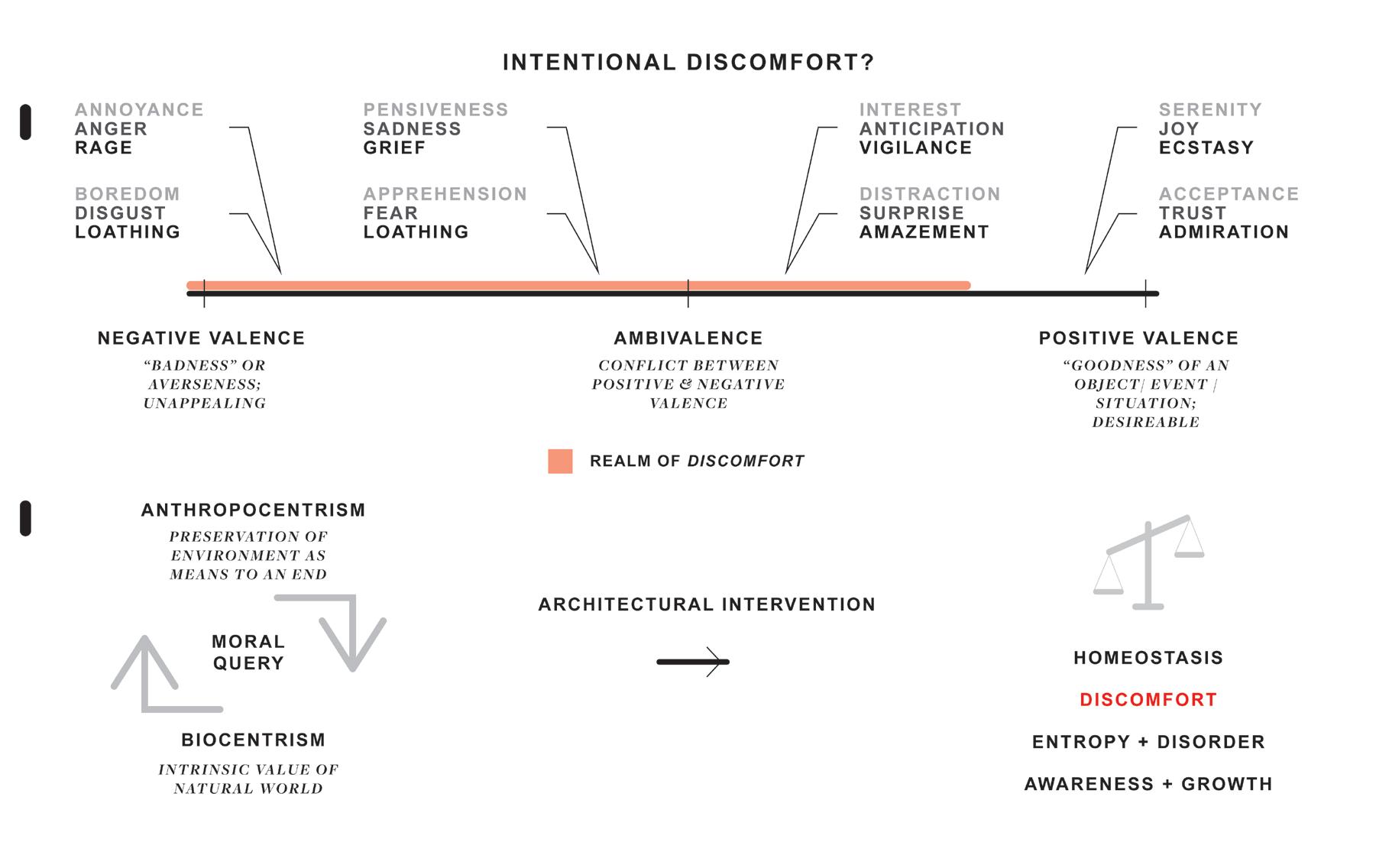

C-07 (Above) Diagram exploring the realm of discomfort and its relation to the psychological concept of valence. This diagram also summarizes the key goals and motivations. Created by the author.

AFFORDANCES

27 26 III SITE 1 KOWLOON WALLED CITY, AN INTRODUCTION CONTEXT & INVESTIGATIONS ANALYSIS 2 3 28 30 36

III . 1 . KWC-INTRO

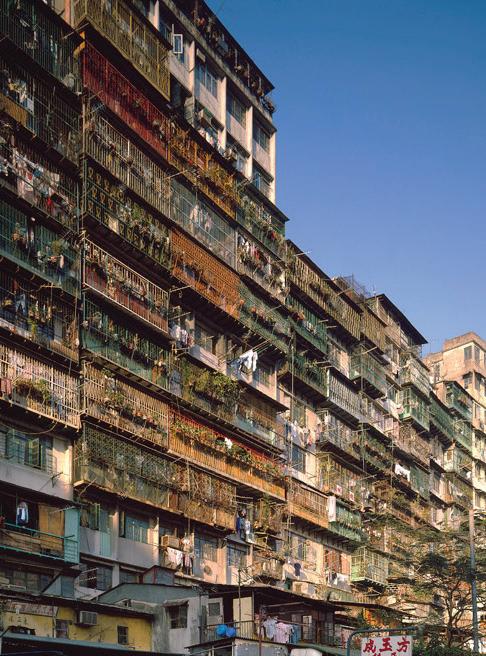

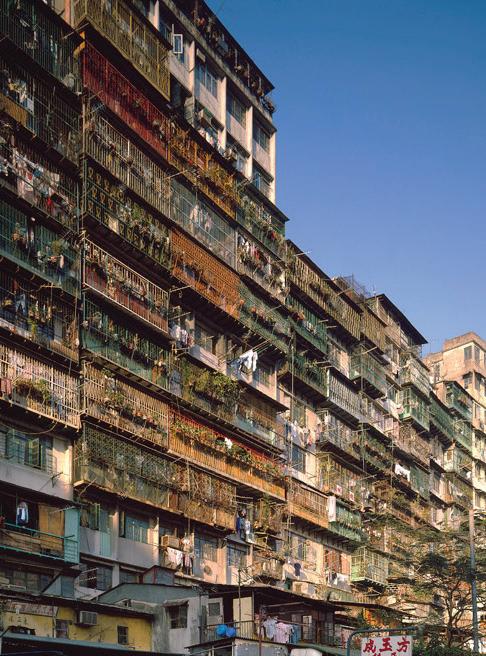

At its peak, Kowloon Walled City was the most densely populated city on Earth. Within a hundredth of a square mile in size, there was a staggering 350 buildings and more than 33,000 residents. Packed tightly against each other, the city’s tower blocks merged into an organic mega structure connected by wires, cables, and pipes and hundreds of alleyways to form a maze-like conglomerate, where inhabitants and frequent visitors could manufacture, receive medical help, and indulge in vices of all kinds.

With little uniformity of shape, height, or material, every surface was covered with postoccupant alterations. On the roof and balconies, television cables and other infrastructural pipes resembled the canopy of a forest, removing any trace of daylight. Hundreds of alleyways and tunnels formed by the accumulation of trash were connected by darkness. Drips of wastewater and moisture relentlessly fell, forcing many residents to use umbrellas “indoors”. The twists and turns of the pathways continued several stories upward, resembling “knotted arteries that burrowed into the heart of the city”.

Organized crime, opium dens, backroom brothels, wooden stalls selling cheap drugs, or offering cheap (often illegal) services catered to every desire, without regulations from outside forces. Still, the inhabitants of Kowloon Walled City adapted, families bonded, and citizens met all their demands. There was no appearance of law, subjecting inhabitants to anarchy. Originally a military fort for roughly 150 soldiers, Kowloon Walled City served as a visual symbol of rejection of British interference in Hong Kong. After the Second Opium War, Britain received control of the entire Kowloon Peninsula, with the exception of the Walled City. Despite negotiations between British and Chinese authorities, the Walled City remained under China’s control until the expectation of battle evacuated the city, making room for missionaries and farmers to move within the walls. Without administrative control from either British or Chinese authorities, the city became a slum, and attempts to evict the new residents by the Hong Kong government met resistance from the Chinese government. During

“A cesspool of iniquity, with heroin divans, brothels and everything unsavory”

Sir Alexander Grantham Governor of Hong Kong 1947-1957

World War II the Japanese occupied Kowloon and tore its walls down. In the aftermath, refugees began to occupy the derelict city.

In 1947, roughly 2,000 squatters took up residence in Kowloon, their huts occupying the footprint of the Walled City even if the walls were torn down. Refugees took advantage of the diplomatic wall, believing that staying within the “wall” would grant them protection from the Chinese government. Over time, the camp grew, becoming increasingly overcrowded, but it was important to stay within the boundaries. Attempts to remove the squatters were unsuccessful or temporary. Claims to sovereignty over Kowloon had no effect on the day-to-day activities inside the Walled City and before long authorities adopted a policy of non-intervention, giving birth to the self-regulated, lawless compound.

A self-government gradually formed to fight against attempts to demolish the compound and develop it into a public park. Offered compensation packages by authorities, 33,000 residents moved out; the remaining residents were forced out by riot police. On March 23, 1993, a solitary, ceremonial swing of a wrecker’s ball hit one of the tower blocks on the edge of the Walled City, commencing the demolition of Kowloon Walled City. It was reduced to dust and rubble within a year 30. In many ways, the Walled City was an embodiment of the internet. In its formative youth, the internet was filled with self-regulating communities, operating without external oversight. Structured only by autonomy and near-exponential growth, these enclaves were inevitably doomed.

DENSITY

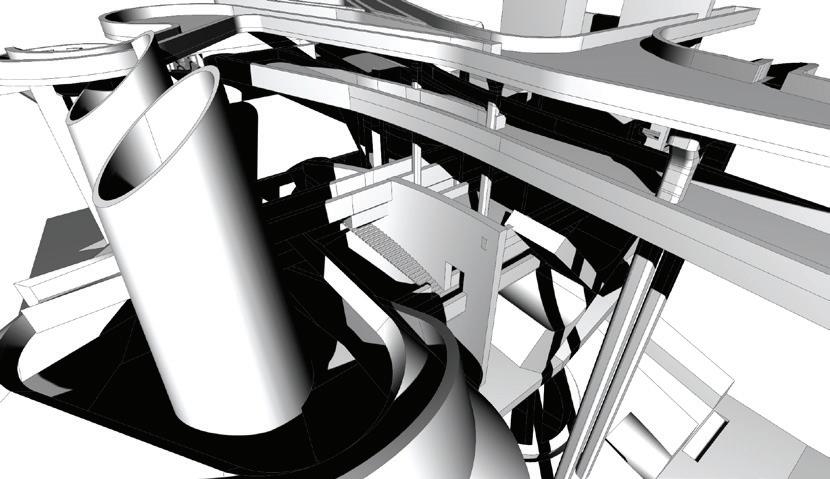

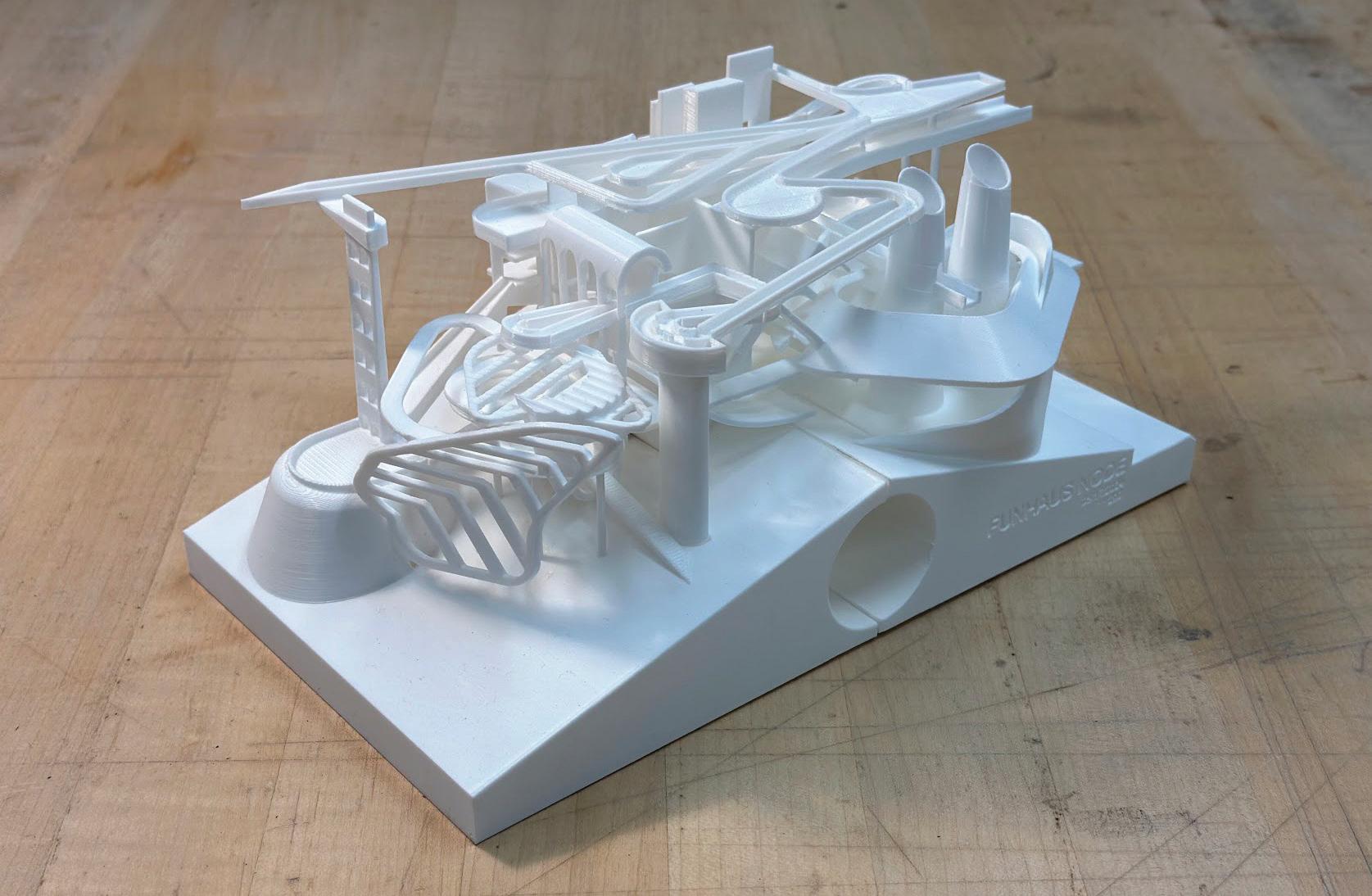

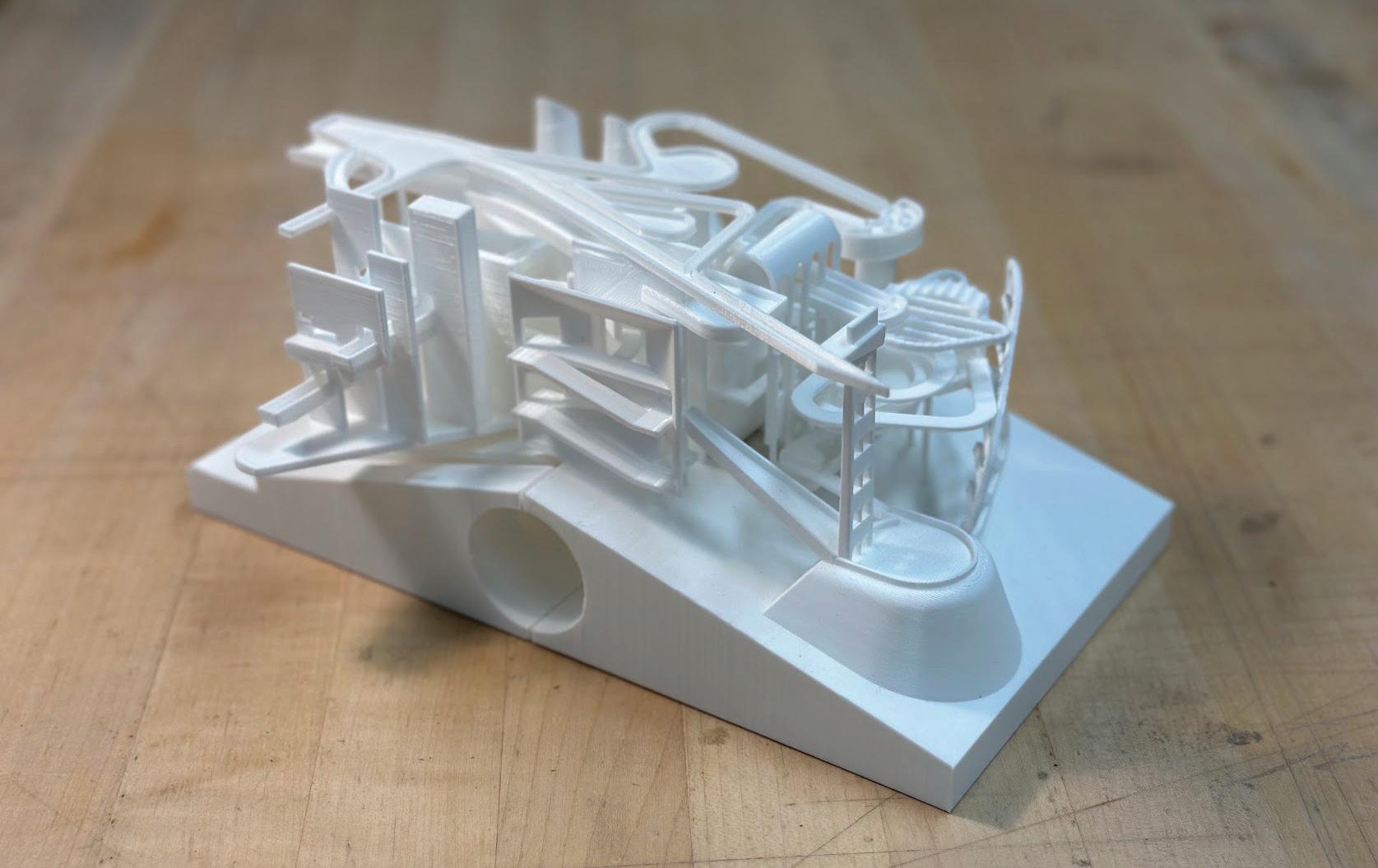

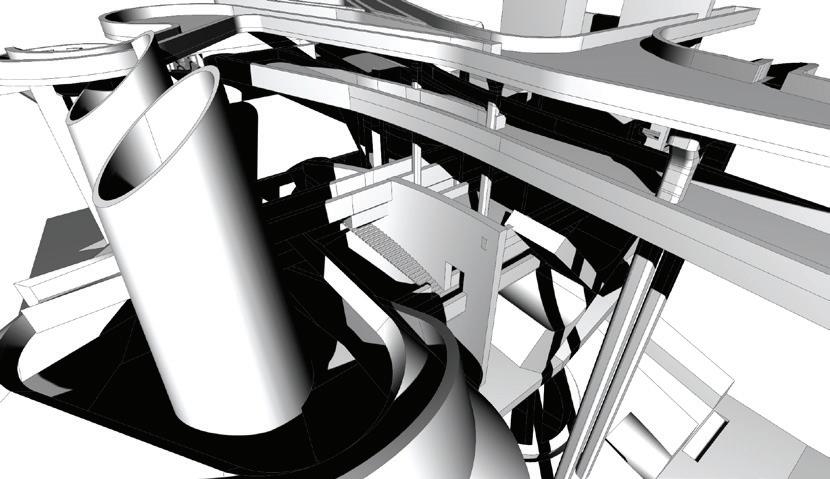

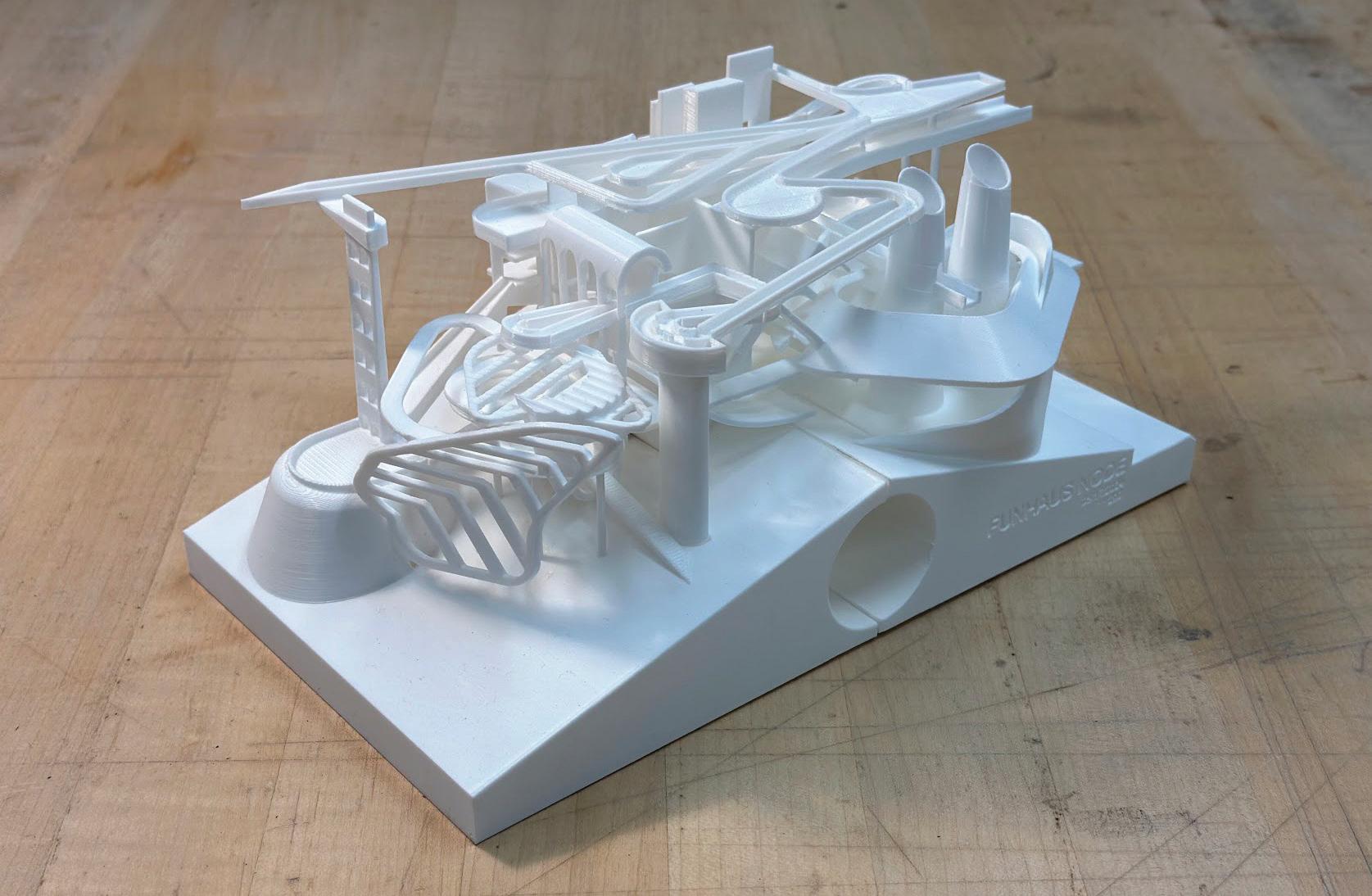

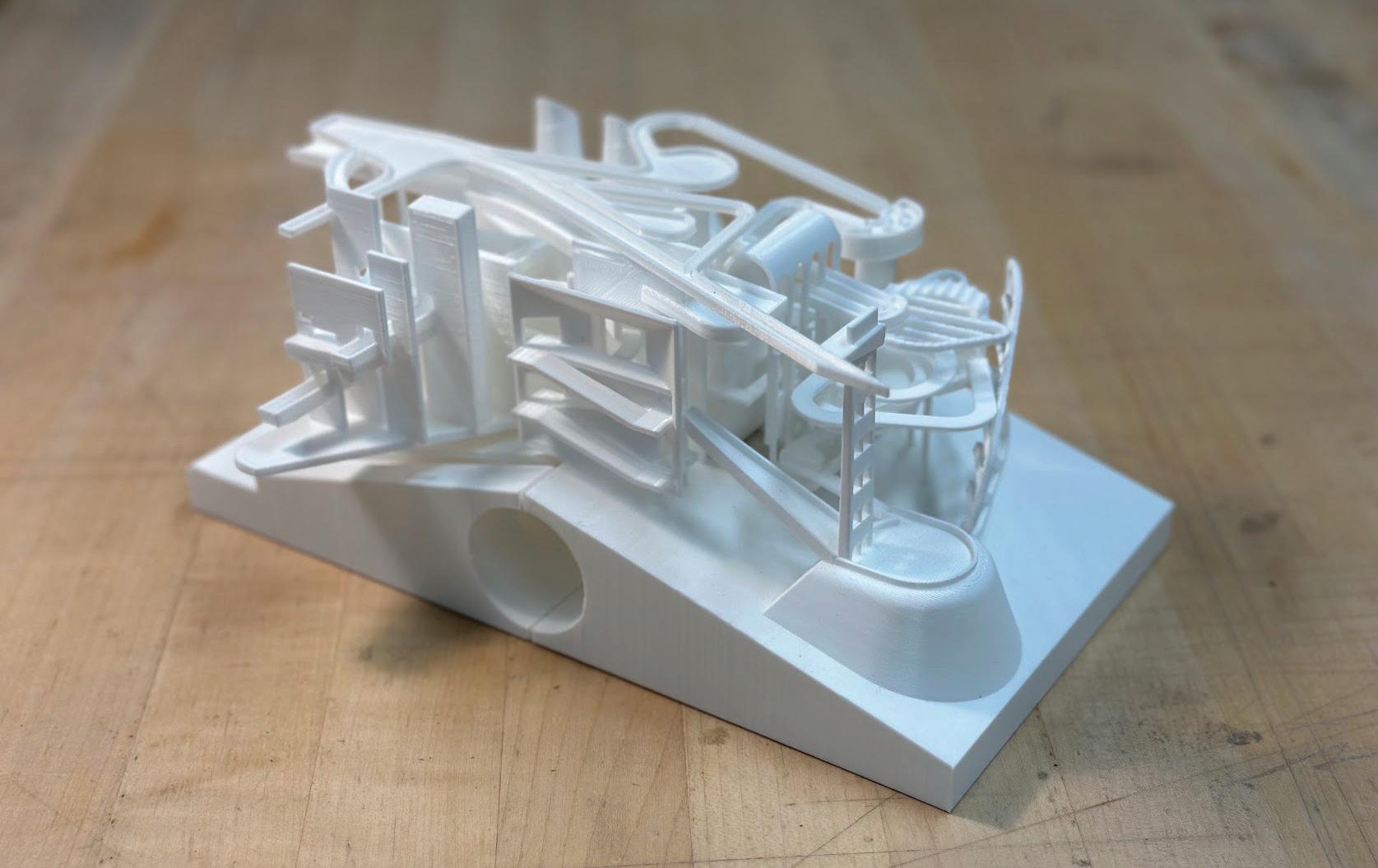

D-00 (Top) 3D Model of the Walled City adapted by the author from existing sources to understand the spatial intricacies of Kowloon Walled City.

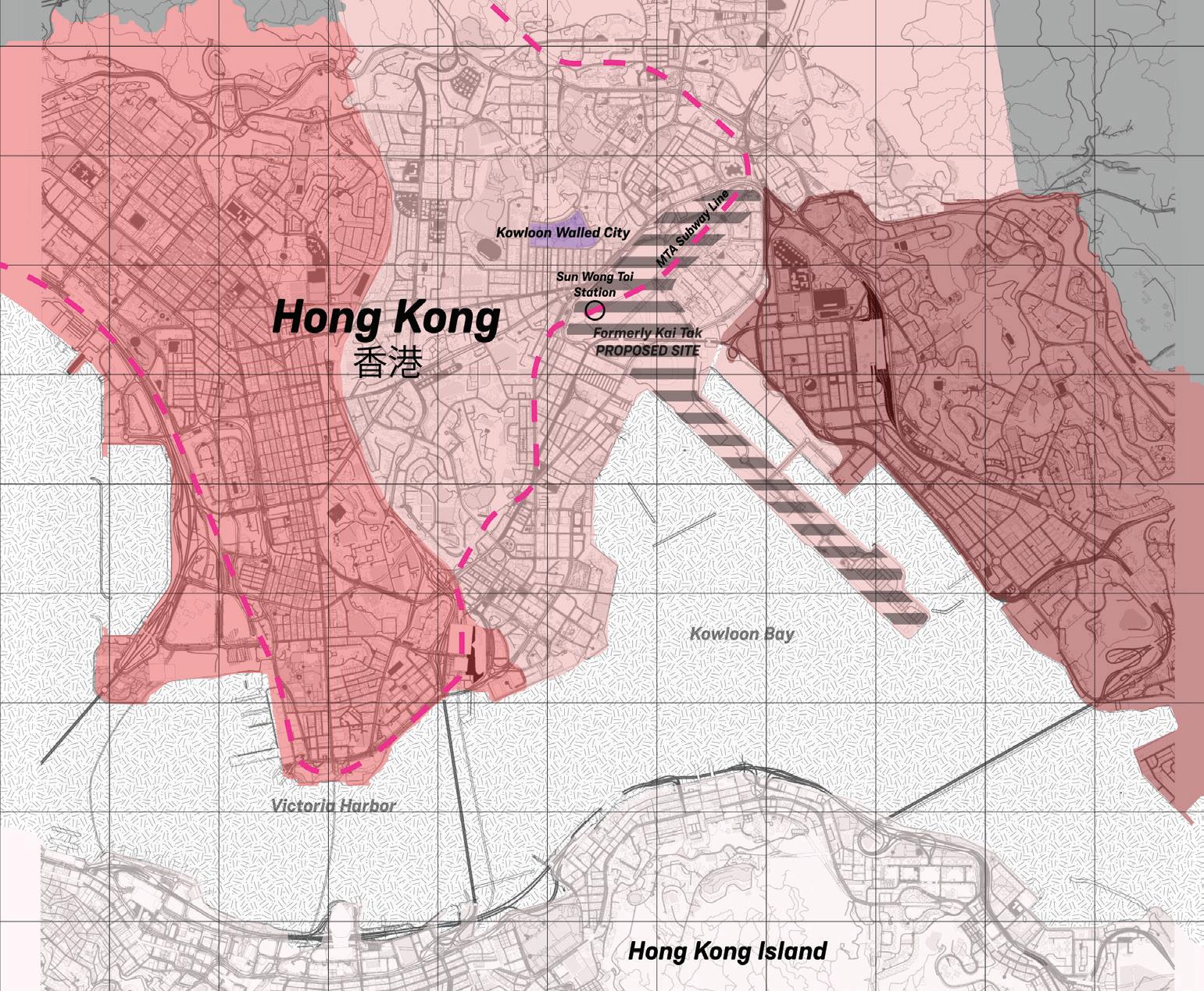

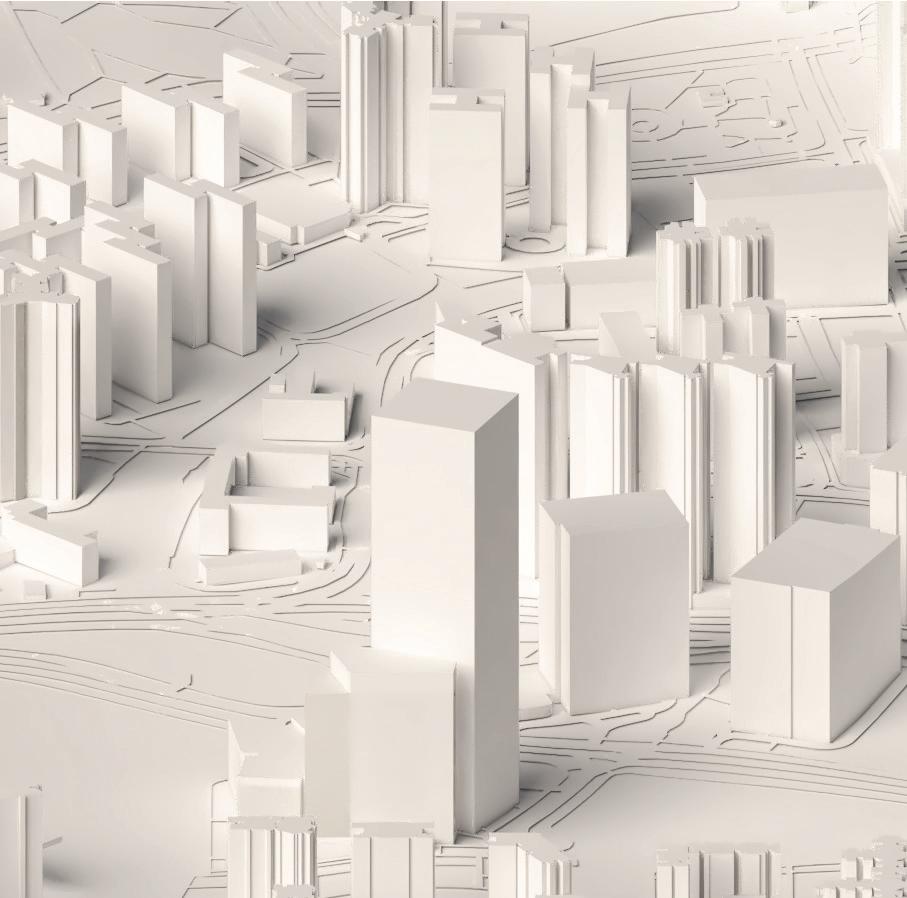

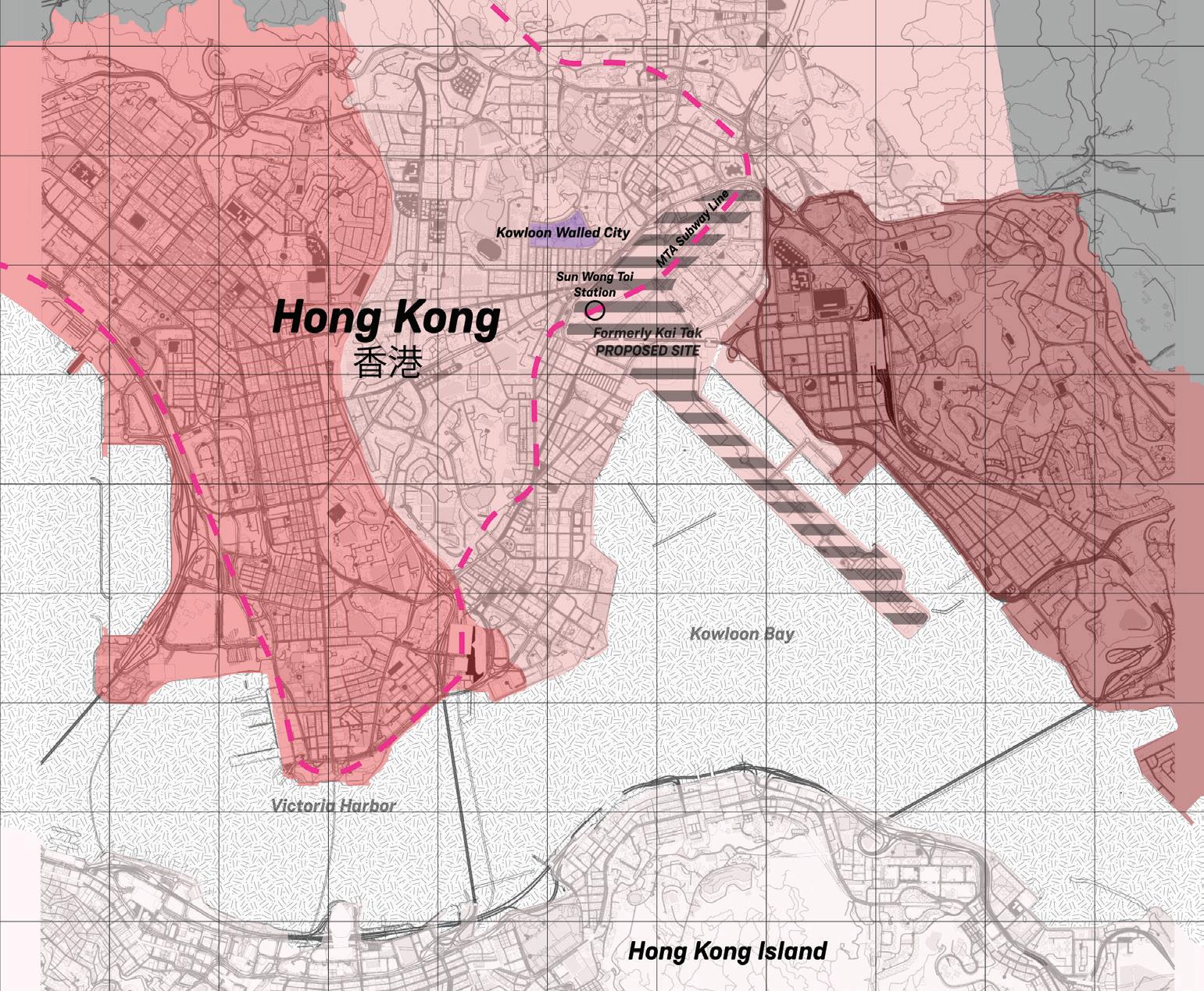

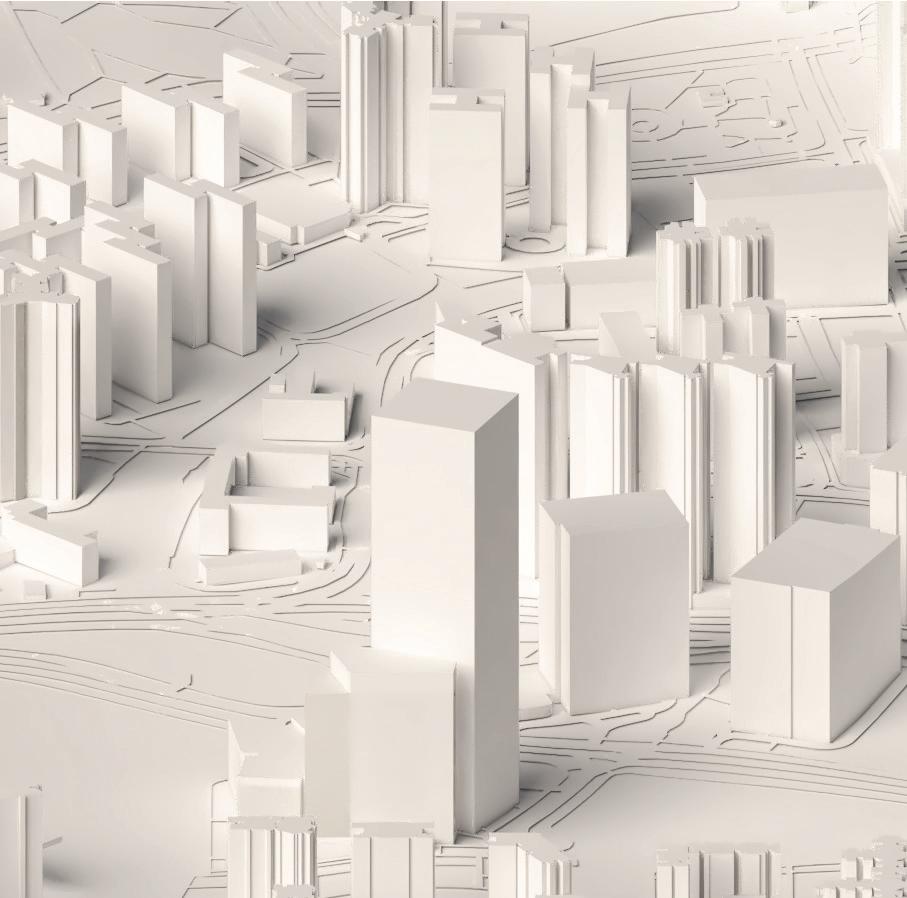

D-01 (Bottom) Site Map of Hong Kong; This drawing shows the density of Kowloon Walled City compared to the rest of Hong Kong, which is already one of the densest cities. Stripped in gray is the proposed site for my urban intervention in in the following section. Created by the author.

29 28

III1KWC INTRO

III1KWC INTRO

AN INTRODUCTION

10,000/km 2 20,000/km 2 30,000/km 2 50,000/km 2 40,000/km

60,000/km

2

2 1,890,000/km 2

30. James Crawford, Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of History’s Greatest Buildings (Picador, 2019)

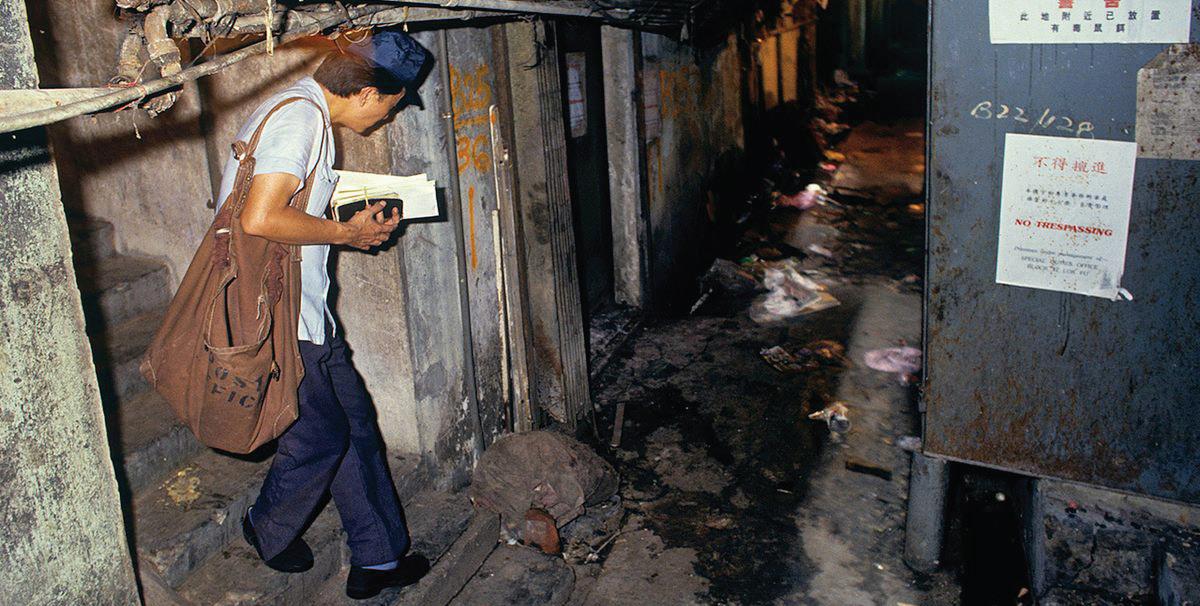

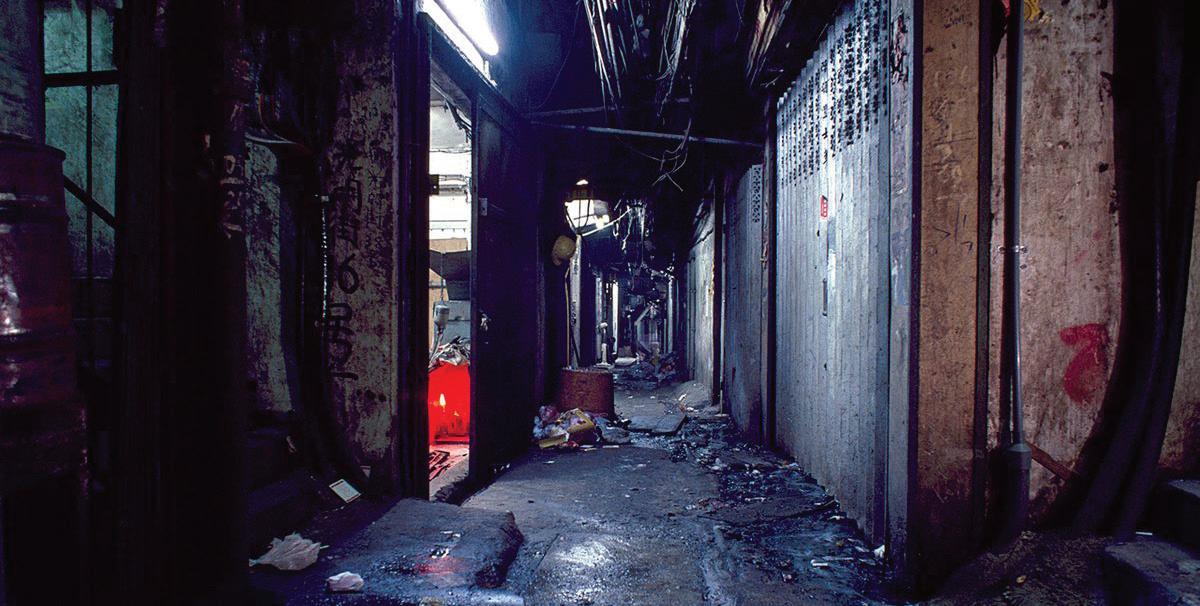

III . 2 . CONTEXT

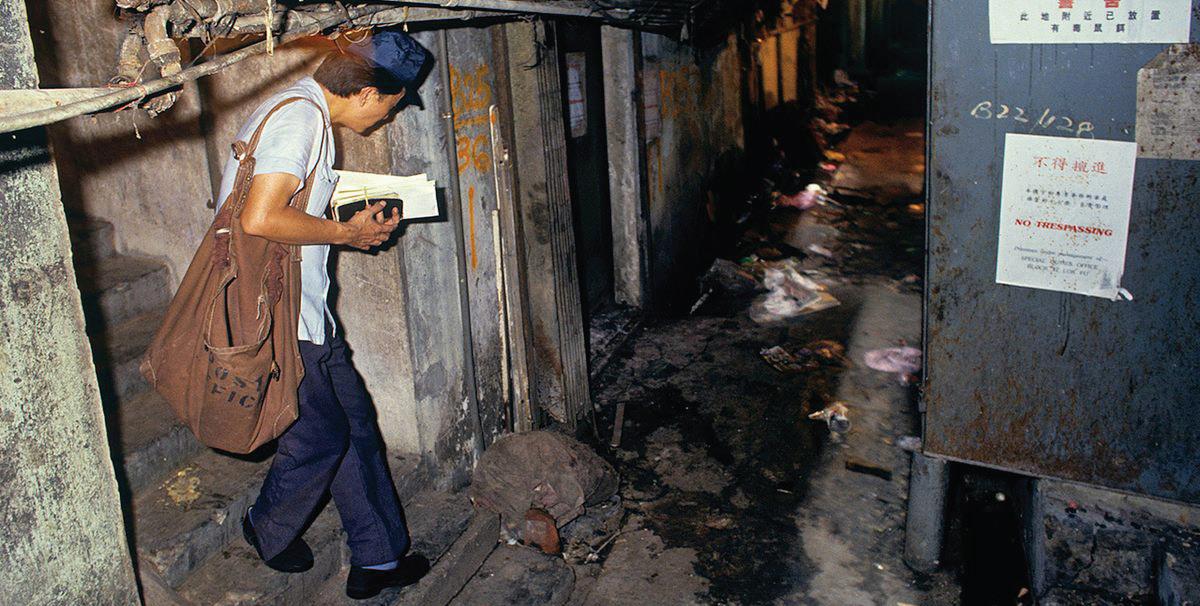

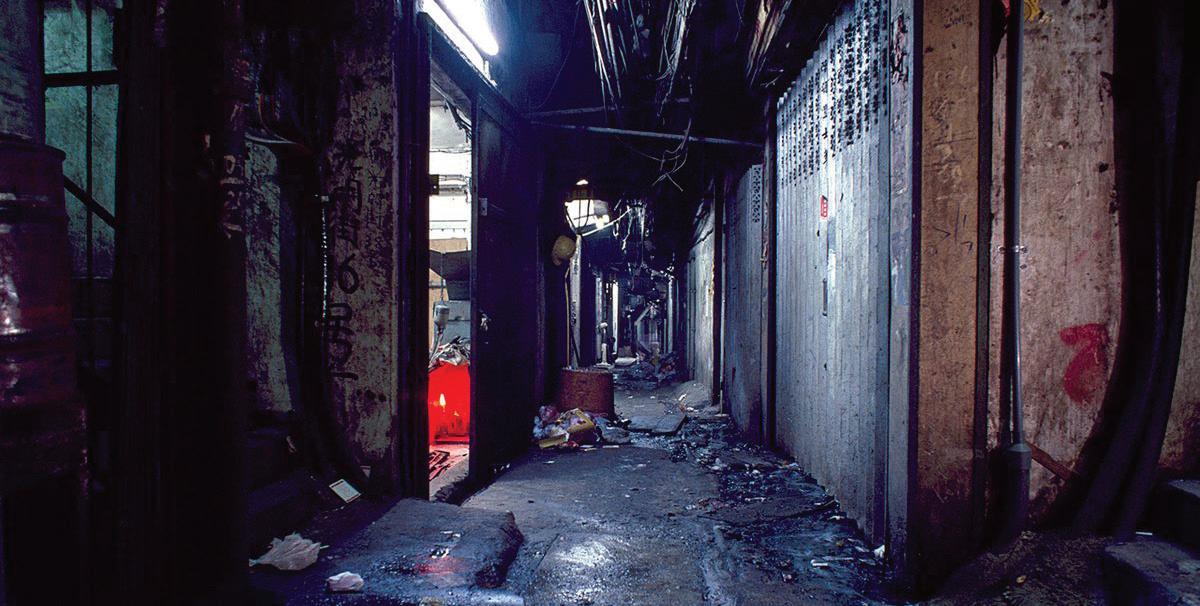

The multitude of narrow tower blocks was densely situated against each other, forming what seemed like a single massive structure. At the very top, make-shift gangways allowed a postman to move from tower to tower. Again, light rarely penetrated down to the alleys and walkways. The aroma of local cuisines, the stench of manufacturing, and the click of mahjong tiles served as a method of pathfinding; each inhabitant knew their unique route of getting to their residence, knowing when and where to avoid solicitors that hid in the dark. Long corridors offered quick glimpses into gambling parlors, prostitution establishments, and opium dens. Without law, even the rats were addicts. Visitors would know where to go for their desired vice by following alleys brimming with life, carefully avoiding the quiet and empty alleys. In the darkness, you could not see the flour dust from noodles covering every surface. Manufacturers of metal and plastic released chemicals into the cramped streets. Still, people were happy to visit the Walled City for their bargain goods and services which anyone could buy by turning a blind eye. Locals called the Walled City Hak Nam—Chinese for the City of Darkness 31

31 30

III2CONTEXT

III2CONTEXT

D-02 (Left) Image of a postman navigating Kowloon Walled City in 1989. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-03 (This page, top) Photo of Kwong Ming “Street”; Photo by Greg Girard

D-04 (This page, bottom) Photo of a temple inside the Walled City; note the grates above it that prevents upper floor trash from falling. Photo by Greg Girard.

CITY OF DARKNESS

31. Greg Girard, City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City (Watermark Publications, 1993)

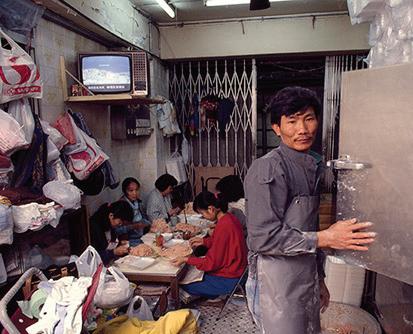

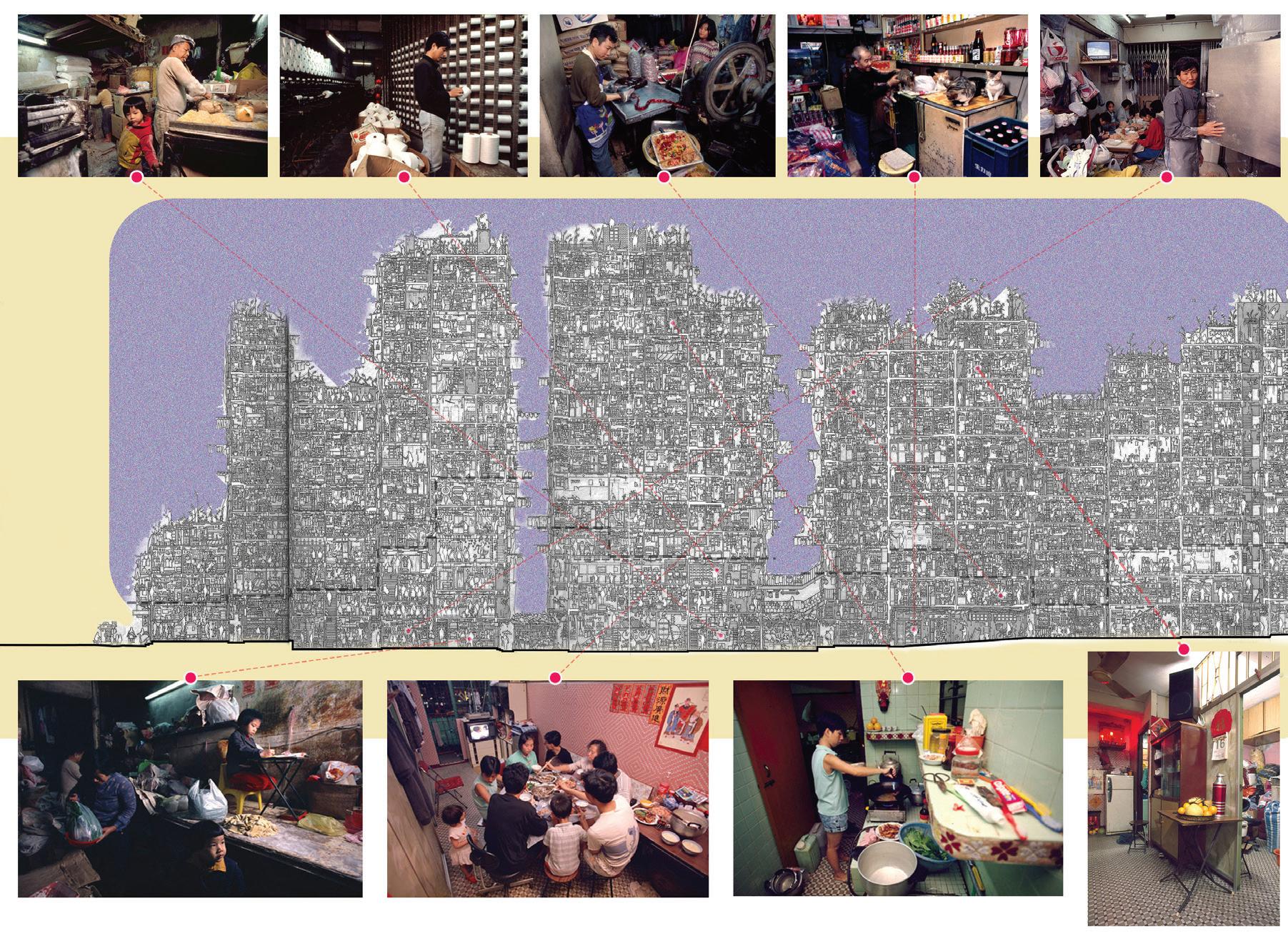

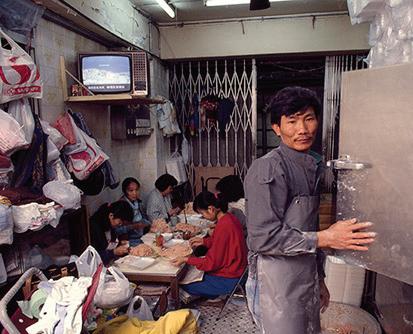

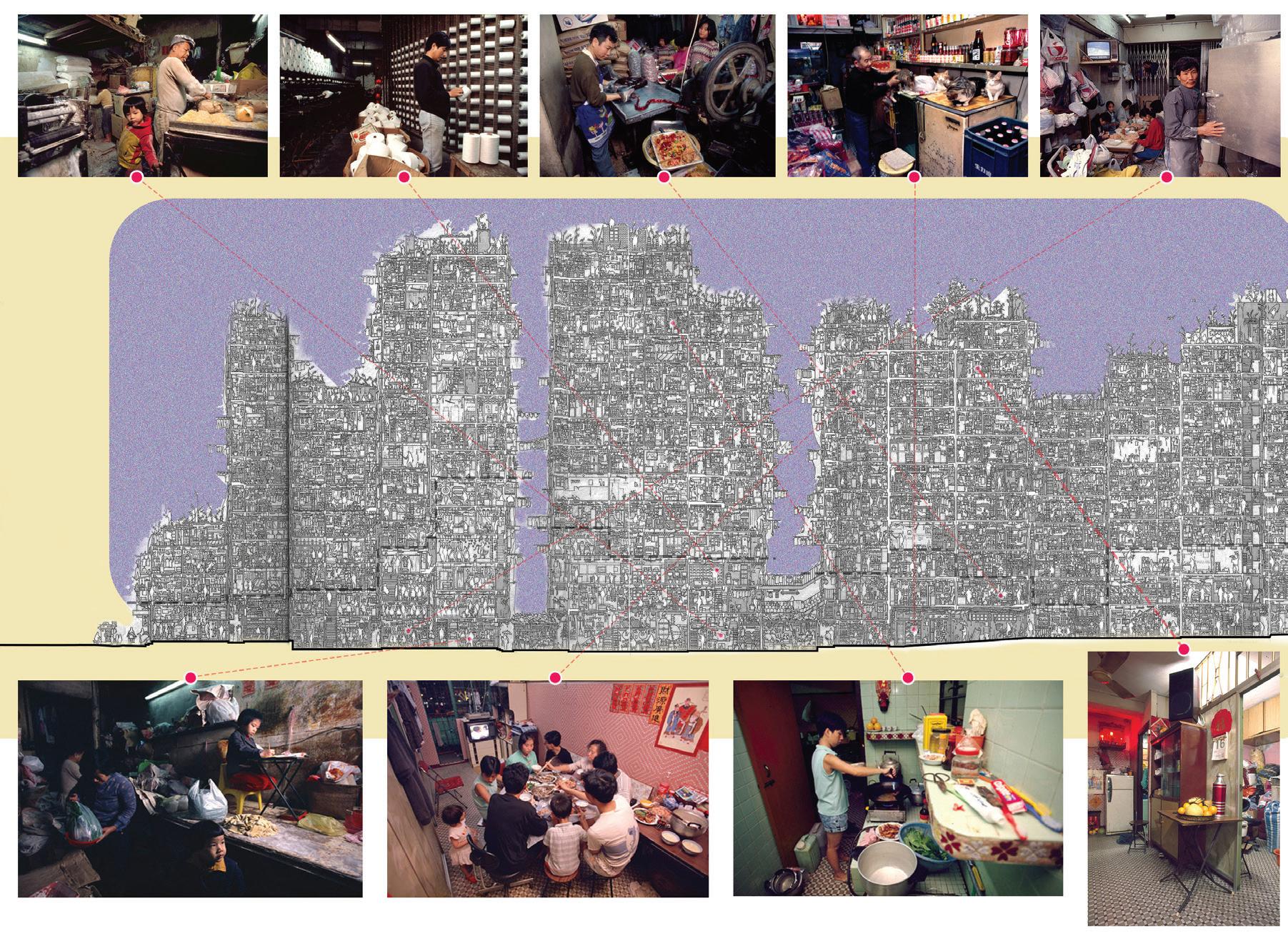

To designers, Kowloon Walled City was an outrageous architectural phenomenon, but at its core it was a community. As observers from the outside, survival seemed near impossible. Emmy Lung of City of Darkness Revisited recorded some stories of residents that were able to thrive in the Walled City. The meaning of home may differ from common Western perspectives and the following photos provide a glimpse into what life was like in this seemingly hostile environment. Accounts from inhabitants reveal that while it was not entirely easy to live and work within the Walled City, it was not necessarily difficult either. Rent was cheap, and it was safe for the most part, but hygiene was practically non-existent (this was a convenience for some, especially manufacturers). Businesses did not need licenses and benefited from visitors who came to sight-see or take advantage of cheap prices.

33 32 III2CONTEXT

III2CONTEXT

D-05 (Above) Photo of a minced fish store with employees of all ages. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-07 (Above) Photo of a resident marinading cuts of meat for his cooked meats store. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-09 (Above) Photo of a family living on the fourth floor in one of the towers in the Walled City. This family included 10 children. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-06 (Above) Photo of a candy store that originally sold soap. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-08 (Above) Photo inside of a resident’s noodle shop. His two daughters are helping him. Photo by Greg Girard.

THE PEOPLE

D-10 (Above) Photo inside a barber shop in the Walled City that serviced many locals. The owner noted that while the shop didn’t make him wealthy, it allowed him to put food on the table. Photo by Greg Girard.

THE CITY

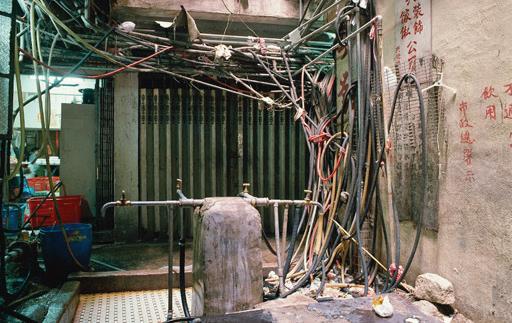

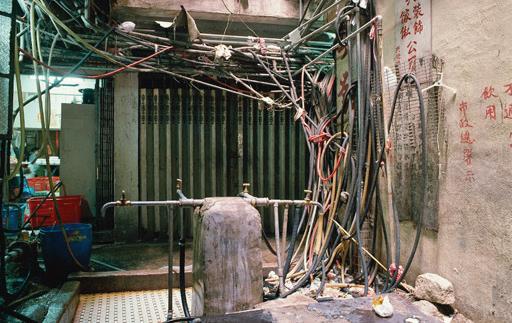

Alleys, stairways, and corridors were reduced to absolute minimums, but that did not stop the day-to-day operations of residents, business owners, and visitors. Many found it difficult to cope with the filth, rubbish, and occasional muggings, but residents adapted and life continued. In Walled City, the water supply was not universal; it was the same for electricity. By 1987, there were only eight freshwater stand-pipes to supply over 35,000 residents and hundreds of businesses and factories with water. Many of these stand-pipes were inconveniently located on the perimeter, where it was easier to install. Connection to a well-water link could cost several thousand dollars depending on how far they were from the well. Of course, not every resident could afford those prices. Even for those connected, there were difficulties with

pumping which meant the supply of water would be available only for a couple of hours each day. Those not connected to stand-pipes took advantage of well water, but in most cases, that water was only suitable for washing and flushing the lavatory.

Greg Girard spent four years photographing the Walled City and believes he and his partner merely scratched the surface. The interconnecting corridors that weaved across the city spanning 14 stories turned the circulation into a maze. For visitors, finding the same place again was next to impossible. If you were unfamiliar with the routes, a process of trial and error and using your nose allowed you to ascend and descend floors. Interestingly, the alleys never felt busy, despite how many people resided in the Walled City.

35 34 III2CONTEXT

III2CONTEXT

D-11 (Left Page) Photo of water stand-pipe. The source of clean water for many residents. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-12 (This Page, Left) Photo inside KWC showcasing the architectural fabric of the space. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-13 (This Page, Right) Photo of the variety of caged balconies that lined KWC’s elevations. They contributed to the richness of Hong Kong’s urban fabric. Photo by Greg Girard.

D-14 (This Page, Bottom) Photo showing the relationship between a manufacturing space and the connecting corridor. Photo by Greg Girard.

III . 3 . ANALYSIS

With little uniformity of shape, height, and building materials, the compound was a living breathing organism with maze-like circulation and erratic program placements. The Walled City was one continuous structure (illusorily so) where you could access everything you needed for daily life. More importantly, this mega-structure grows and evolves. Fiona Hawthorne called it “an energetic, industrious patchwork of chaos with a strange, compelling beauty.” Left alone and lacking government oversight, the settlement grew and continued to grow like an organism. Additional structures were built cheaply and quickly to accommodate the rapid influx of residents and refugees. Those seeking to escape poverty or capitalize on the unregulated haven converged on the Walled City. Without fire, labor, or safety codes, growth was organic and near-exponential. Businesses in Kowloon Walled City flourished due to unparalleled prices for goods and services, and the lack of oversight allowed them to remain that way.

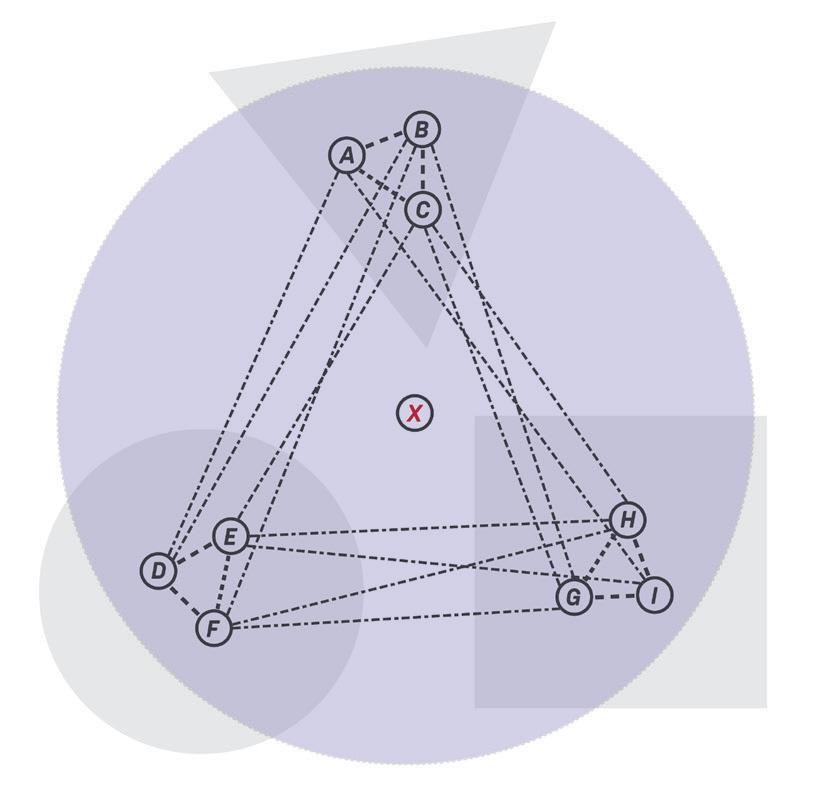

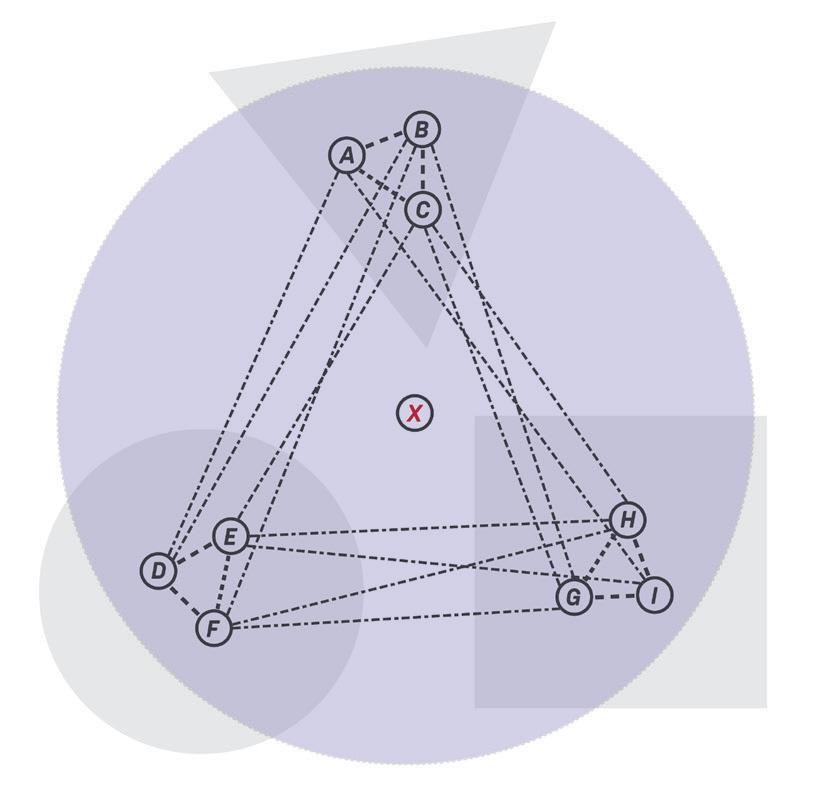

Like the rhizome, there was no definitive center point and new structures sprouted quickly in different directions. The rapid nature of growth and expansion connected the city in unexpected and unconventional ways. Roughly 350 buildings were merged by the rhizomatic growth into a singular mega-structure. Businesses strategically leveraged this by expanding into similar programs to lure in new customers. New buildings attached to existing buildings and integrated themselves accordingly. With each new addition to the city, the pathways changed slightly and formed new connection points. At certain junction points (nodes), convenience stores serviced the surrounding residents. There were multiple points of connection vertically and horizontally. This method of expansion is not without its faults but the rhizomatic concepts demonstrated at Kowloon could prove useful architecturally.

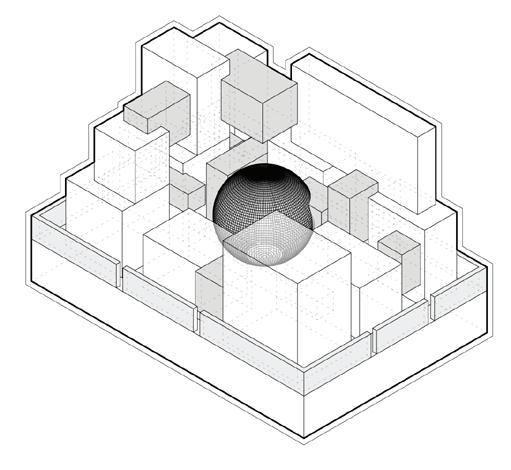

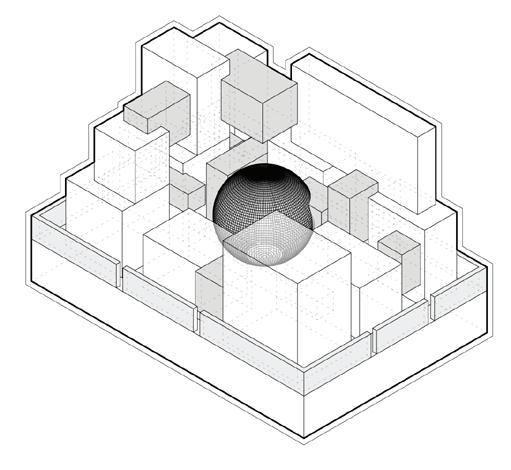

UPWARD/INWARD GROWTH

Though it served a diplomatic purpose, the boundary of Kowloon Walled City is physically abrupt and unforgiving, even after the wall from its time as a military fort was torn down. This was one of the main conditions that helped the city become inextricably interconnected. However, the same condition led to its deterioration and lack of hygiene. The rhizomatic growth, when bound, continues to grow inward, increasing the density until it is physically impossible to fit more, which necessitates an upward expansion. Ultimately, this was limited by the capability of cheap and quick construction, resulting in the mega-structure terminating at 14 stories tall.

There was a social heart of the city; this was the only place you could look directly up and

see the sky instead of more built structures. In section, the density was visceral and unparalleled 32 Unlike Brazilian favelas, the Walled City’s footprint restrictions required upward expansion. While the favelas clung to the steep hillsides of Rio de Janeiro, you could identify a unified ground-level often with stores and factories leading into one another. Crowding, unsanitary conditions, pollution, disease, rudimentary waste disposal methods, and jerry-rigged infrastructure were common in places of natural/organic growth. Unregulated tenant alterations could prove problematic, but the social and physical cohesion created by the Walled City is worth a consideration.

37 36

III3ANALYSIS

III3ANALYSIS

D-15 (Above) Diagram representing rhizomic connections. Lacking structure, there are connections between multiple multiplicities. Traditionally planning departments plan each buildings function. With the rhizome, there is no planning. Created by the author.

D-16 (Above) Diagram explaining the integrated nature of the Walled City. Forced to expand within strict borders, towers become taller and the spaces between towers lessened as the resident population grew. Created by the author.

D-17 (Above) Sectional drawing linked to interior views of life at Kowloon Walled City. Created by the author.

PART ARCHITECTURE, PART ORGANISM

32. Hiroaki Kani, JP Oversized (Iwanami Shoten, Publishers, 1997); A team of Japanese researchers, architects, engineers, and city planners were led by historian and cultural anthropologist Hiroaki Kani. They managed to document the Walled City before it was demolished and published their findings in this book which included meticulously drawn cross-sections. The Japanese fascination with KWC led to some of the only drawn documentation of the now-demolished city.

SELF-REGULATED

Self-regulating and self-determining, the city that occupied a tiny block of territory was a petri dish of urban theory. Amid mounting tensions between the Chinese and British authorities, refugees and squatters were left to fend for themselves and do as they saw fit. Evolving from a temporary refugee camp into a permanent settlement founded on the ruins of an old military fort, residents of Kowloon Walled City ignored the external political games and built a life with no tax, regulation, planning systems, or police enforcement. These conditions allowed visitors and residents to abuse every conceivable vice, making it the epicenter of Hong Kong’s narcotics trade at one point. Crime, both organized and spontaneous, did not deter entrepreneurs who found the low rents and lack of regulations appealing. Residents demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to adapt to ever-changing conditions.

With no requirement for planning or building regulations, Kowloon builders erected

towers established on shaky foundations.

Exacerbated by the speed at which these structures were built, these “high-rises” would suffer from settlement and subsidence. Buildings began to lean against each other leading residents to call them “lovers’ buildings.”

True, the Walled City was a collection of buildings, but they began to merge into a single structure, an organism designed to meet the living requirements of residents. Despite any official governmental interference, the community in the city self-organized and solved problems in real time. Collectively, residents upheld the city’s continuity and stability even amid the ever-evolving chaos.

Anchored by the will to survive, the community kept Kowloon Walled City alive until its demolition in 1994. Now the city exists only in photographs and distant memories. Yet, the essence of the Walled City lingers on and continues to fascinate those who stumble upon the marvel.

39 38 III3ANALYSIS III3ANALYSIS

D-18 (Above) Axo drawing showcasing some of the industries that dominated Kowloon Walled City. Created by the author.

D-19 (This page, top) Photo of an opium den in the Walled City. These temporary “clinics” prevented users from being caught in possession of drugs. Photo by Greg Girard. D-20 (This page, bottom) A surveillance photo of a clinic taken from a surrounding roof. Clinics employed people as lookouts, making it extremely difficult to catch drug dealers.

Photo by Greg Girard.

41 40 IV

1 DESIGN OVERVIEW PROCESS INTERVENTION 2 3 42 46 48

DESIGN + INTERVENTION

IV . 1 . DESIGN-OVERVIEW

In our extremely unrelated, heterogeneous, polyvalent, unconventional, informal, decentralized, and spread-out world, which is increasingly freed of ideologies, how can we design, or again, project buildings that possess a general validity and common value beyond the particular meaning they might have for one private individual?

Valeri Olgiati Non-Referential Architecture

Precedents of design prioritize comfort and leisure, but this oversight leads to a stagnant population motivated by the dichotomy of comfort and discomfort. There exists a need to re-invent architecture as a catalyst for innovation and a stimulus for the mind and body. Looking into the strategic introduction of discomfort within our routine behaviors, how can courage exploration, foster creativity, and enhance the overall wellbeing of the masses while still maintaining the seminal practical functionalities of architecture past ?

To understand architecture as an impetus for progress, we must first garner a rudimentary understanding of the human psyche, especially its relation to designed spaces. The immediately obvious emotion/ feeling we want to produce with designed interventions would be happiness and comfort. However, does this lead to longterm progression and genuine well-being? An architecture of influence must concern itself with both ends of the spectrum: comfort and discomfort. Beginning as an argument against the dichotomy of work and life, of comfort and discomfort, the thesis seeks to change that narrative with a hybridization of the first three places as described by sociology. By introducing rhizomatic growth within a confined space, there is the opportunity for novel configurations space due to density. A megastructure that encourages communal cooperation to solve shared problems helps create a malleable architecture. While designers can strategically intervene, a malleable architecture respects the

temporality of needs and desires and therefore grows to reflect the intentions behind human behavior.

At its peak, Kowloon Walled City was housing nearly 33,000 people in only around 6 acres of land, making it the densest city on earth before it was demolished for reasons of hygiene and safety. William Gibson called it a “hive of dreams,” but at the same time it was pure unregulated, organic chaos. chose this site to examine human discomfort, but instead learned about resiliency and adaptability on a city-scale. The negotiation between function, space, and infrastructure makes this site uniquely applicable to my thesis endeavors.

A petri dish of urban theory, Kowloon Walled City was dense, informal, and self-regulated without interference from external factors. It was part architecture, part organism with all the intricacies of a living, breathing machine. Connected only by human relationships, innumerable cables and water pipes the form of this complex grew in a maze-like manner with little to no uniformity.

Without law and true governmental pressures, citizens of Kowloon Walled City created their own bureaucracy to take care of issues that affected the collective. A city of darkness, both physically and metaphorically, KWC forced its inhabitants to adapt within the tight boundaries set by the outer walls. They forced the architecture to meet their needs and demands by building as needed against any formal codes.

Essentially unmappable by traditional methods, life and experience in the walled city is hard to illustrate. Even videographic evidence of the city fails to depict the true slum and density. Yet, people flourished and found ways to live. They altered their routines and utilized every nook and cranny . It might be considered uncomfortable by western standards, but the inhabitants of Kowloon Walled City took advantage of the lawlessness, and continues to interest designers with their exploits and adaptations.

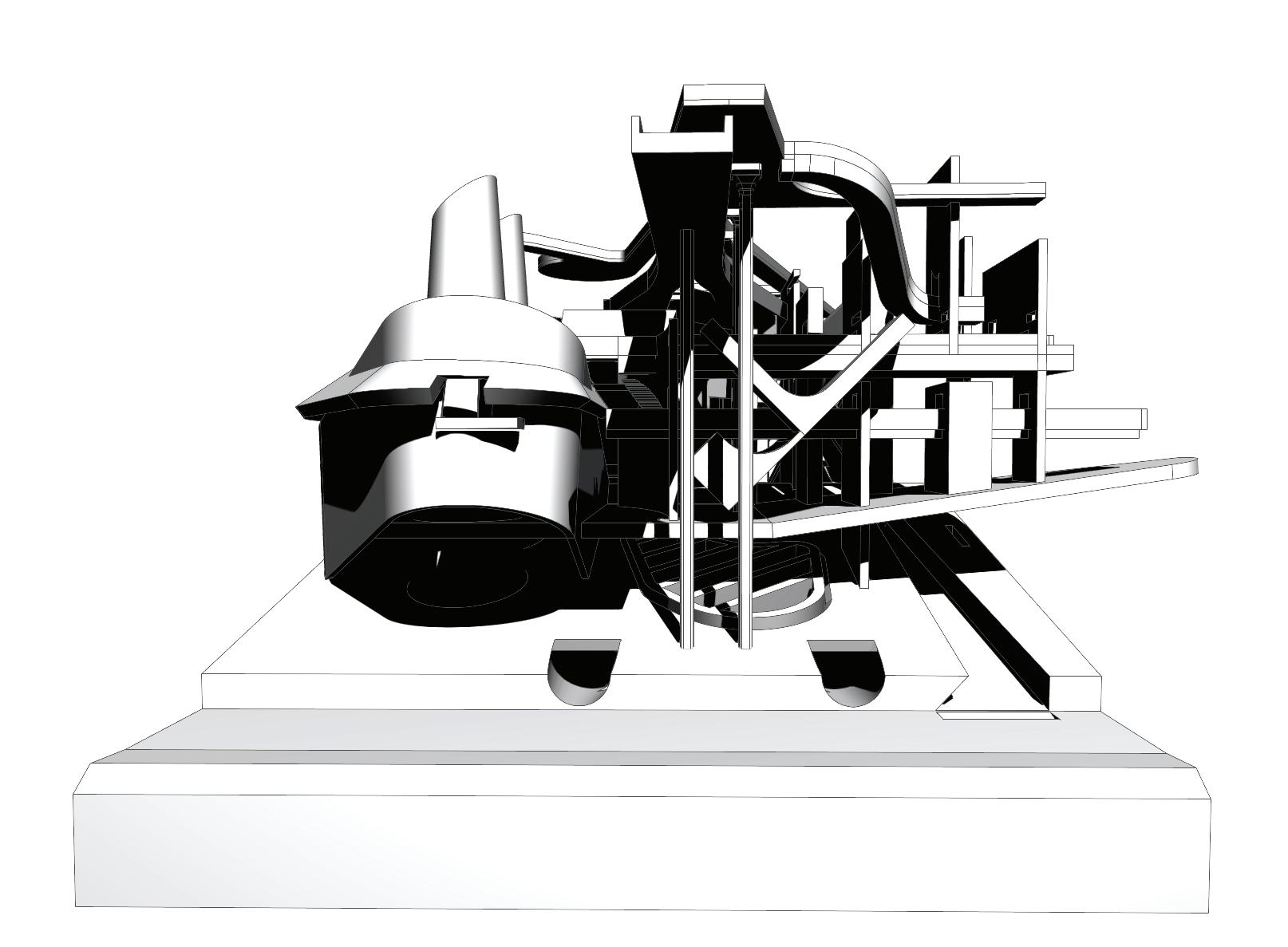

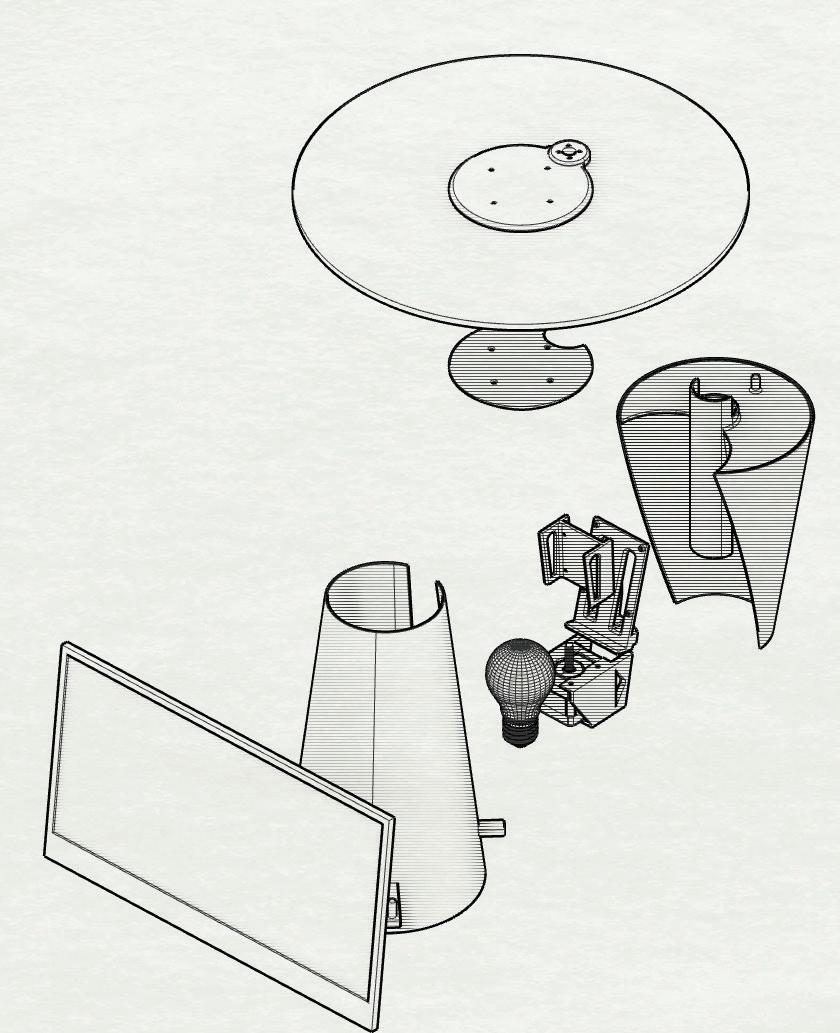

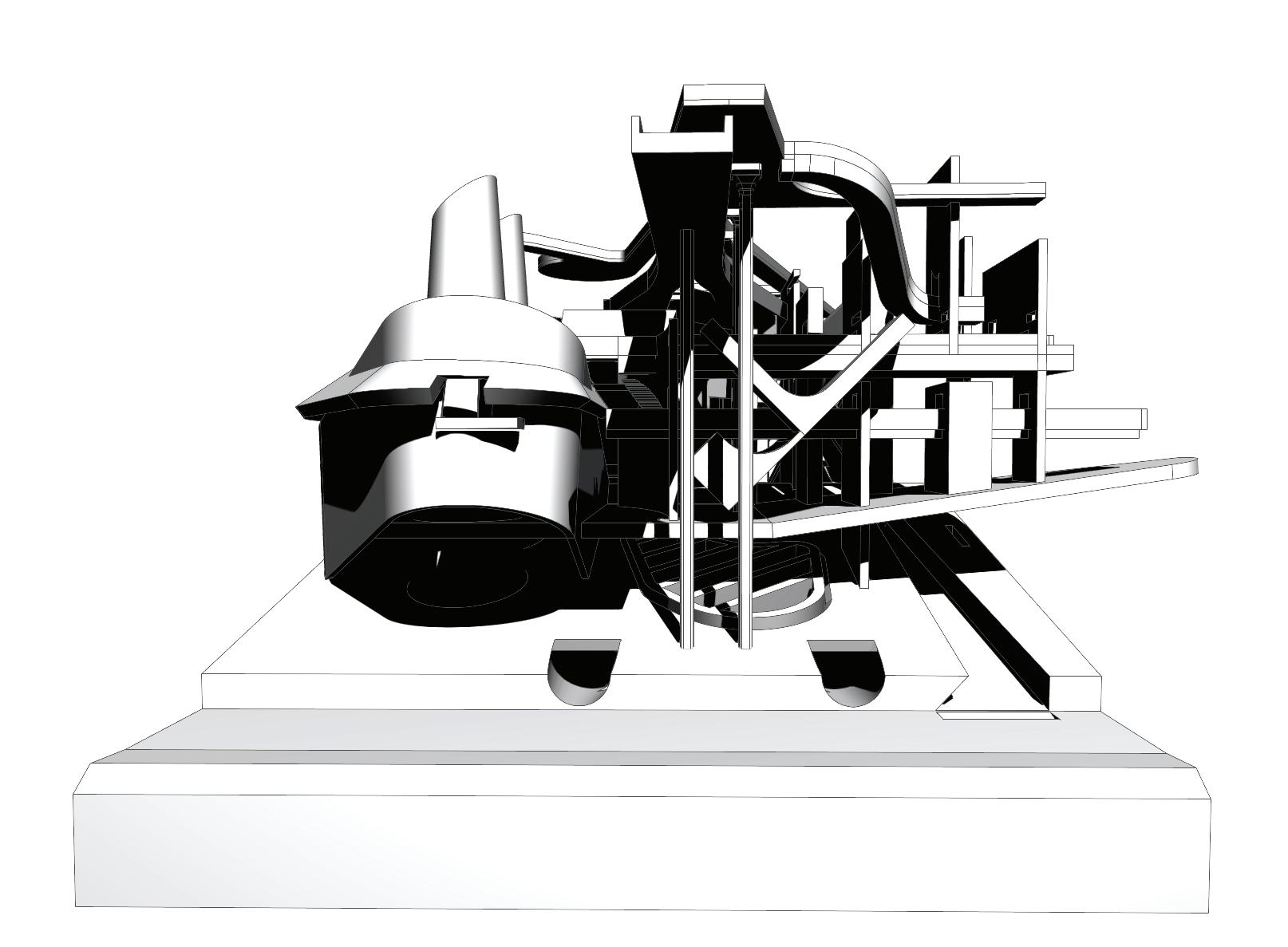

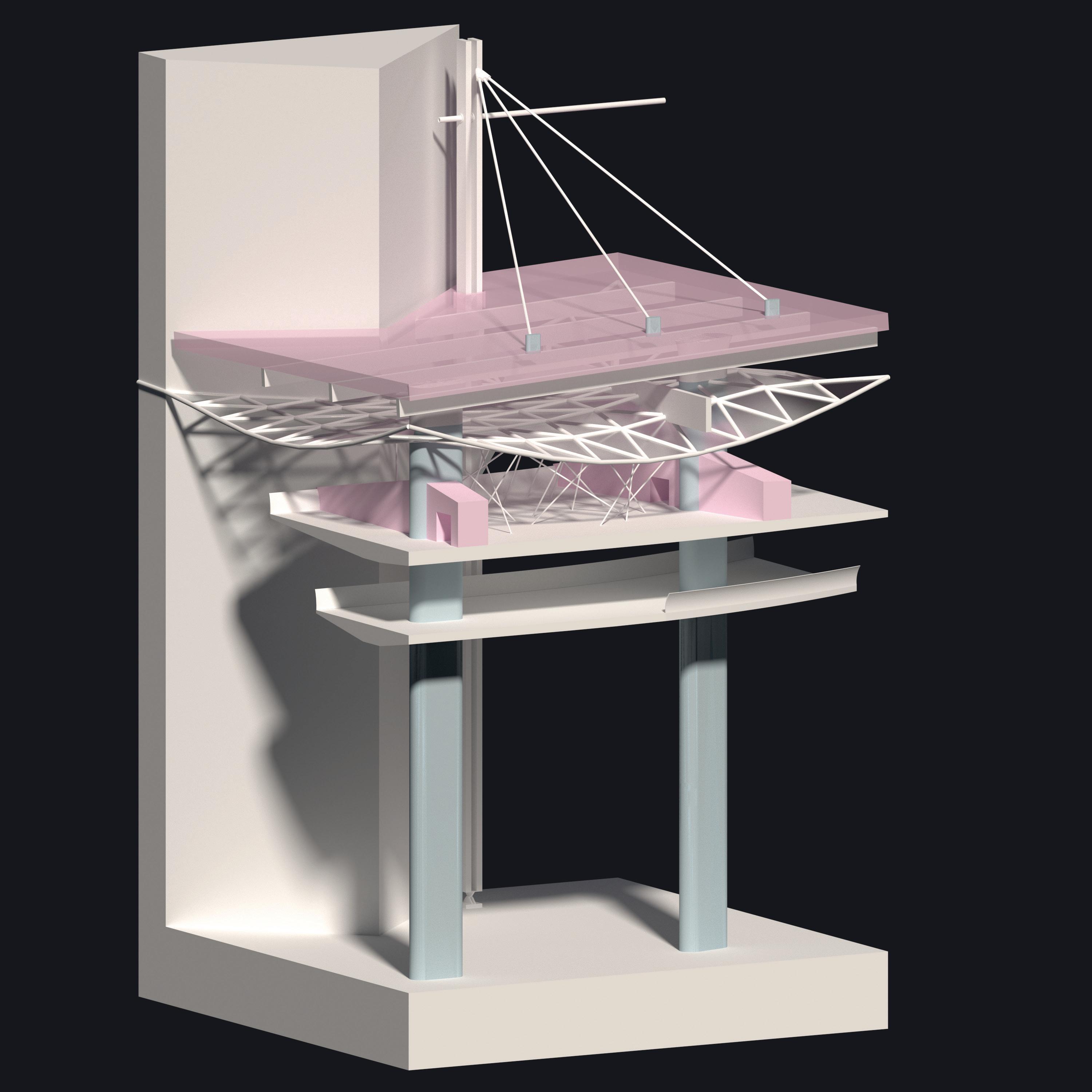

Centered around the concept of a living conglomerate, the core of this structure serves as the organs. While the “organ” supports life in this structure, it will require maintenance and care, forming a symbiotic relationship between man and

the built structure. Waste, water, heat, electricity, and other utilities are provided by the organ but, unlike municipal utility services, inhabitants are responsible for the lifecycle of each utility. In this analogy, the circulatory networks are the bones of this organism, and its exterior walls/constraints are the skin.

The ultimate goal is to create a framework for introducing discomfort into design and how it can contribute to our well-being alongside comfort. Similar to mental health, there are stigmas against discomfort but its potential benefits merit an examination.

43 42

IV1DESIGN-OVERVIEW

IV1DESIGN-OVERVIEW INTENTIONS

E-01 (Above) House in Miyamoto by Tato Architects/ Yo Shimada; Expressive of novel/unusual spatial layouts, multisensory transformable space, and high customizability.

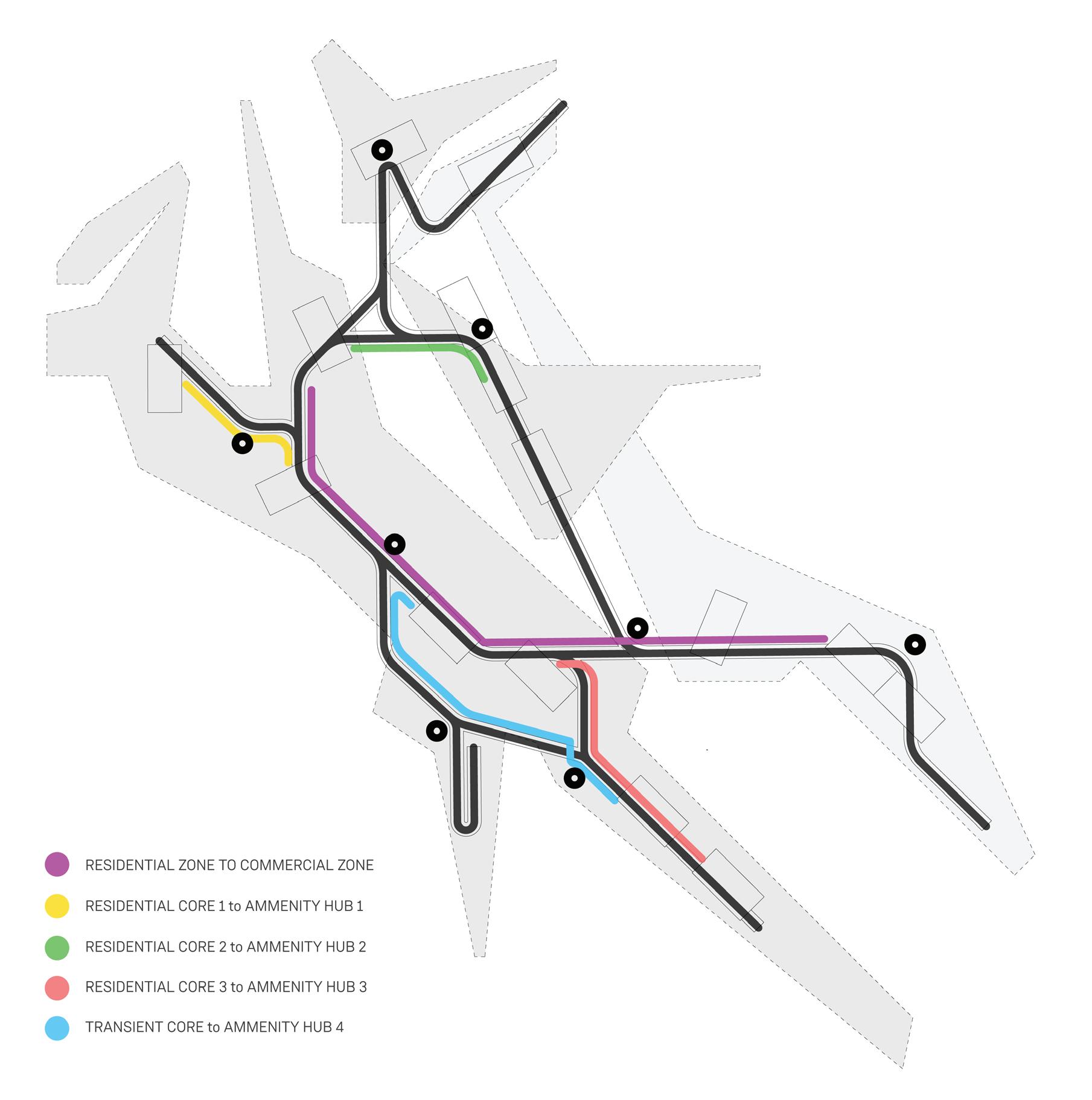

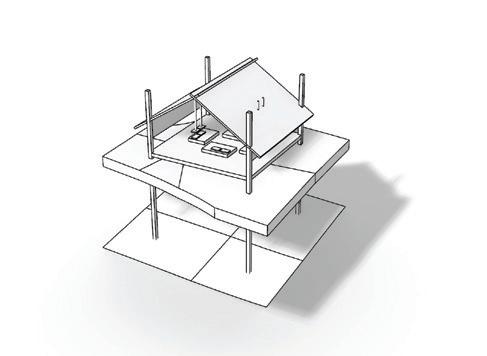

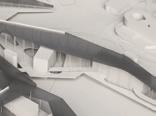

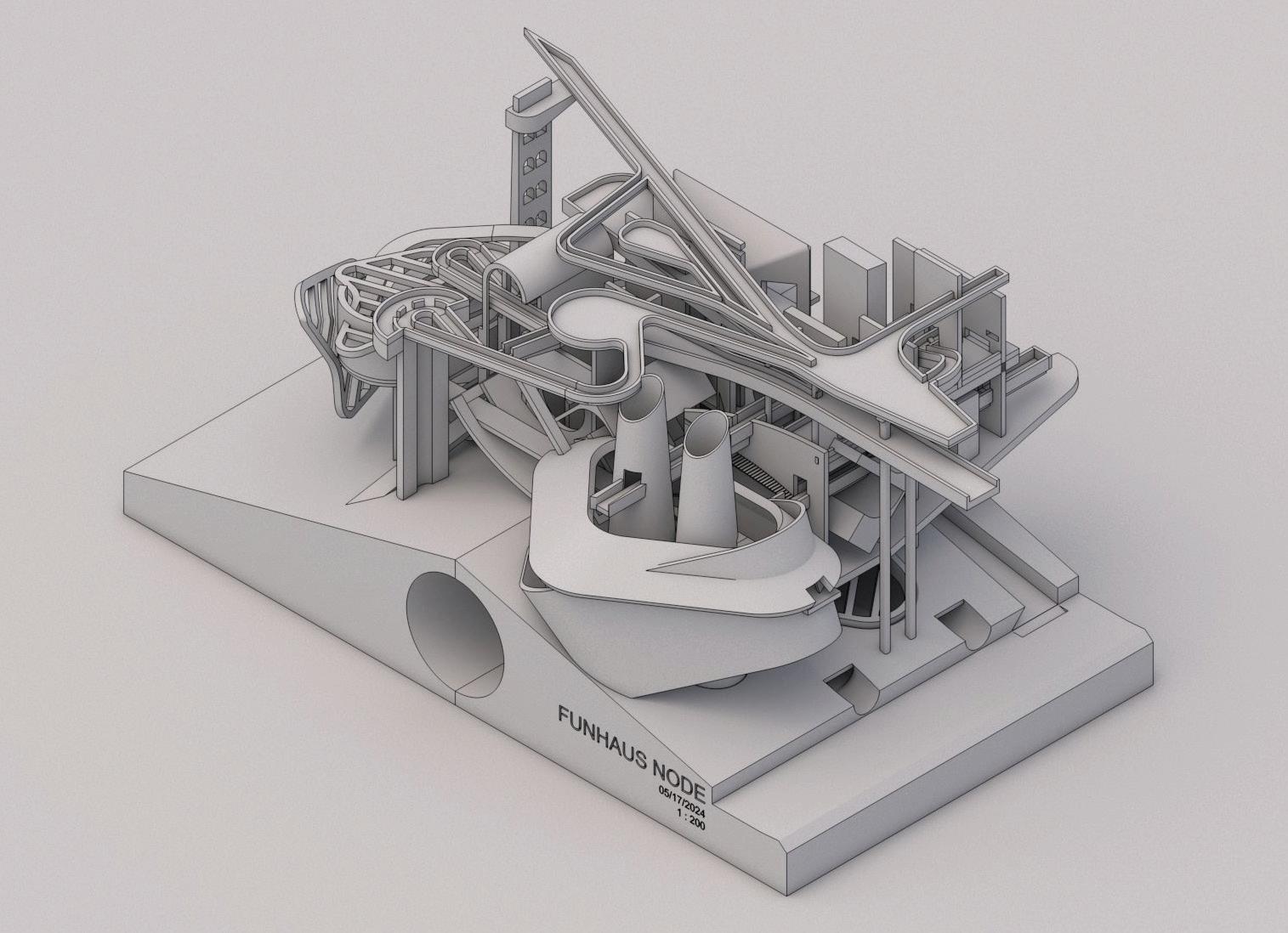

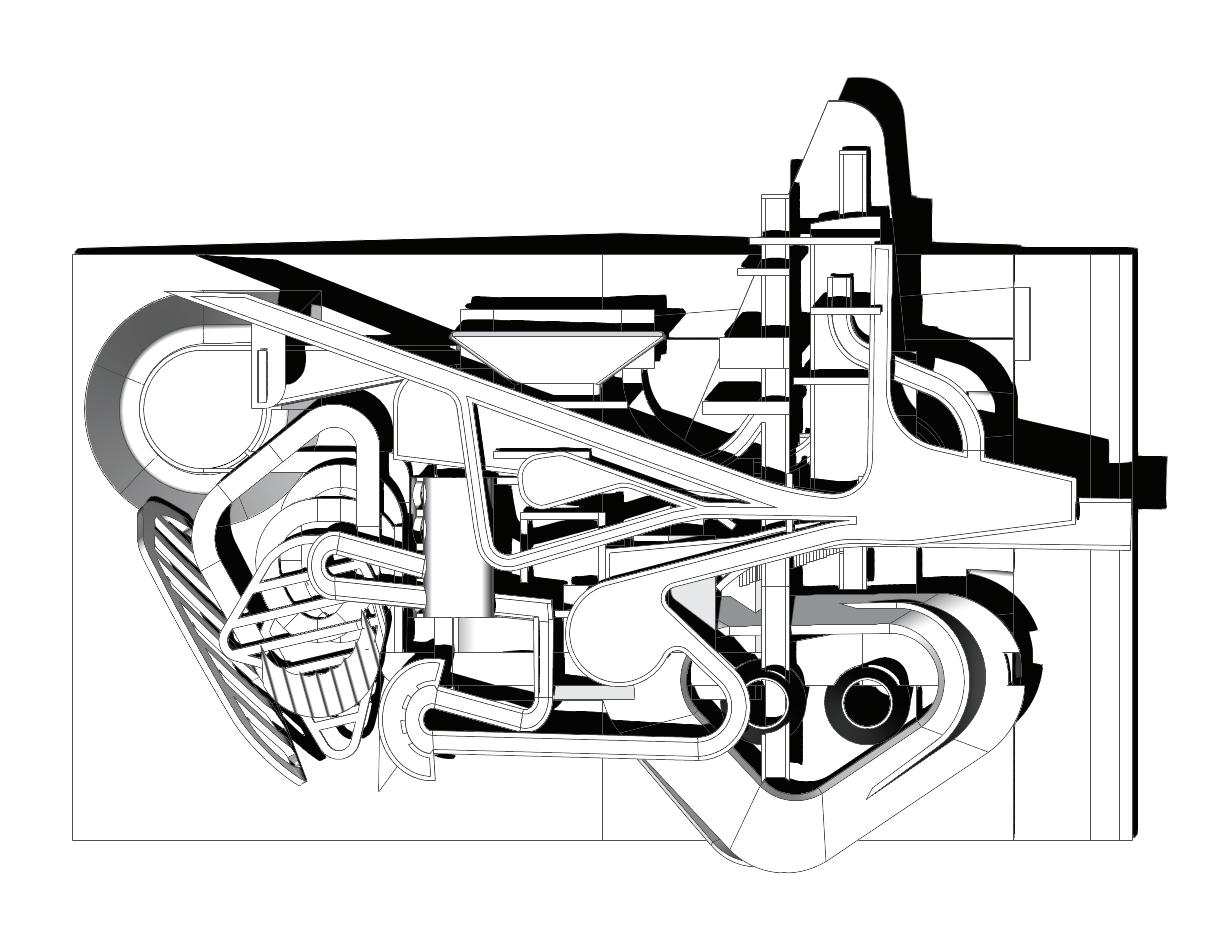

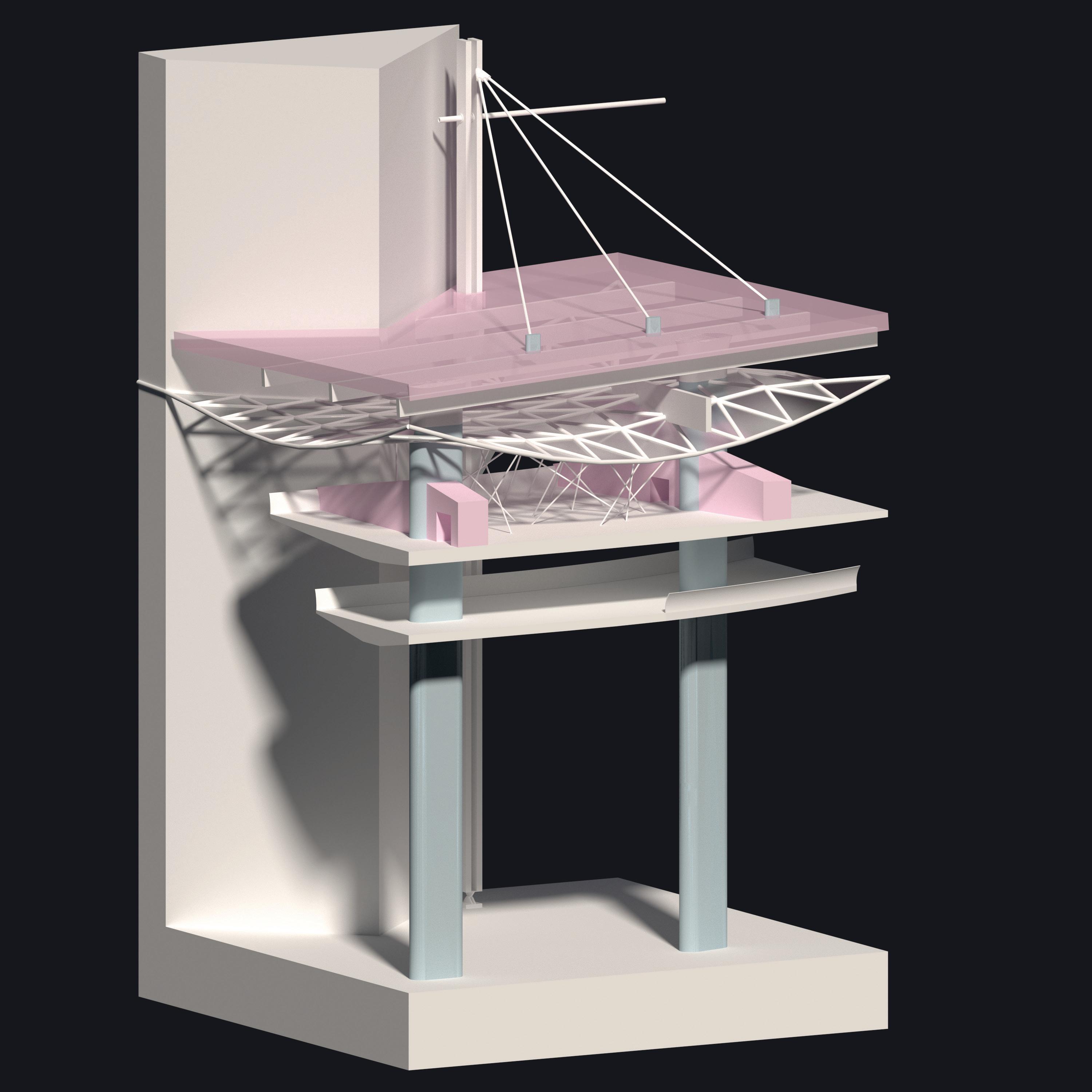

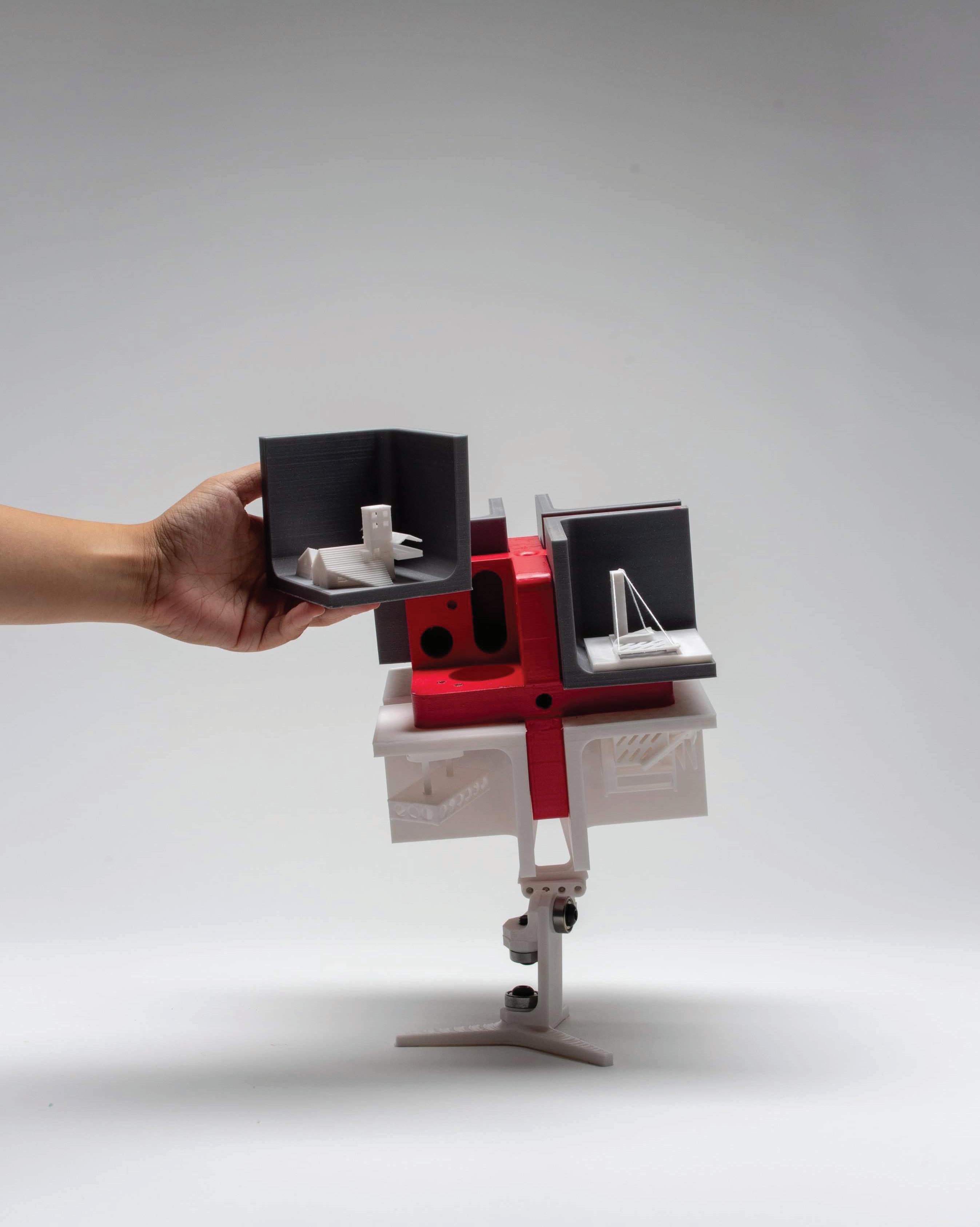

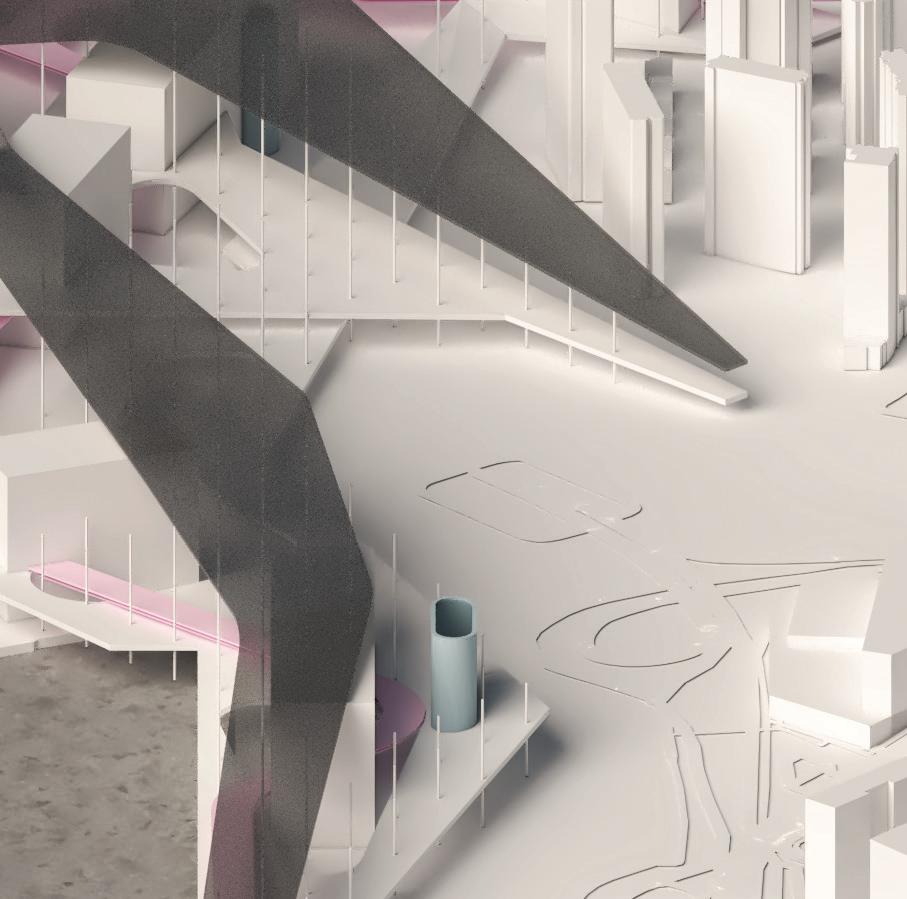

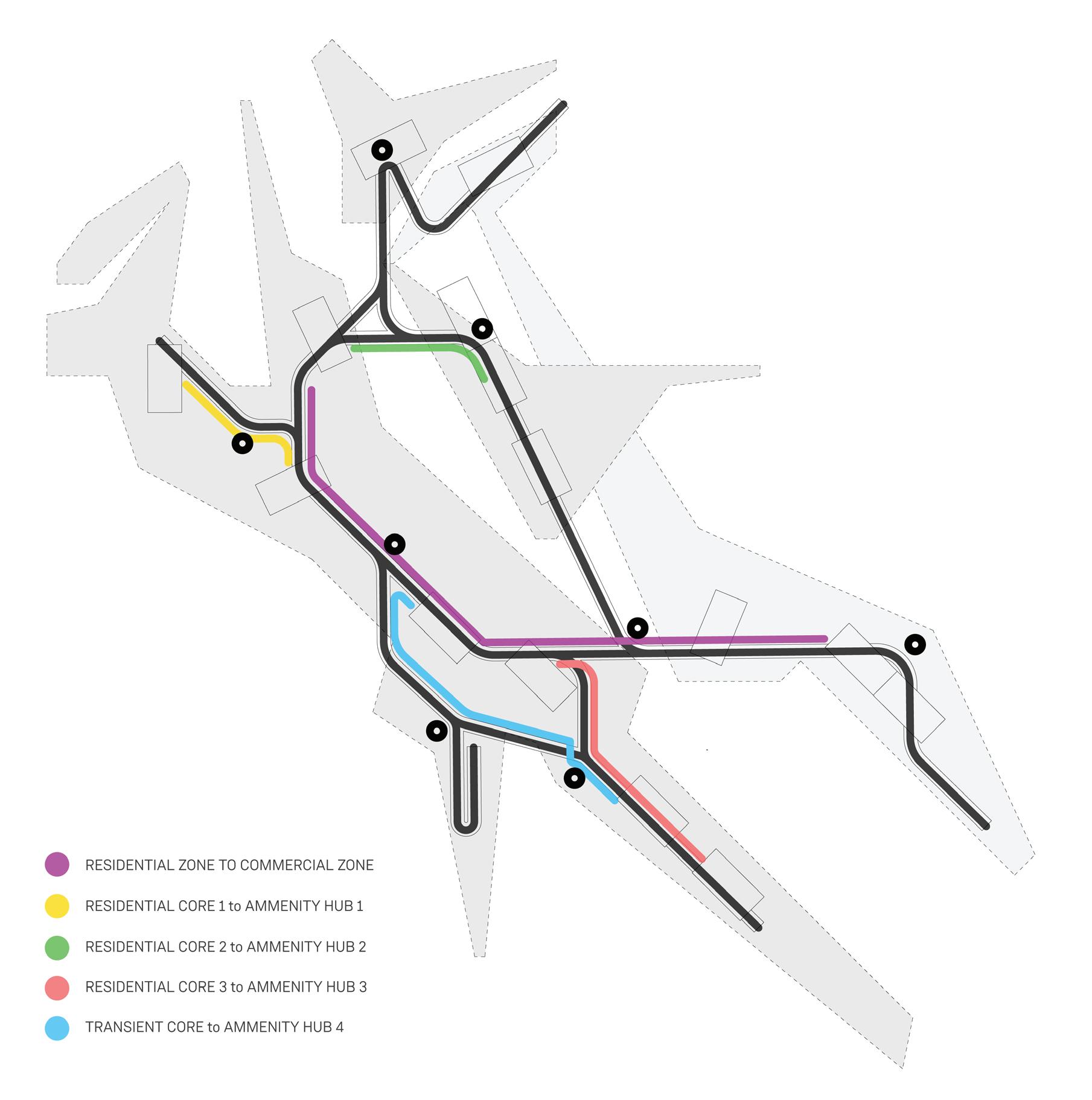

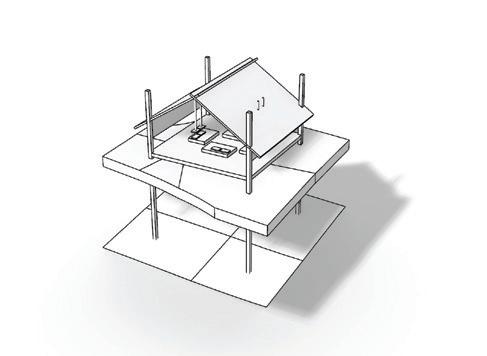

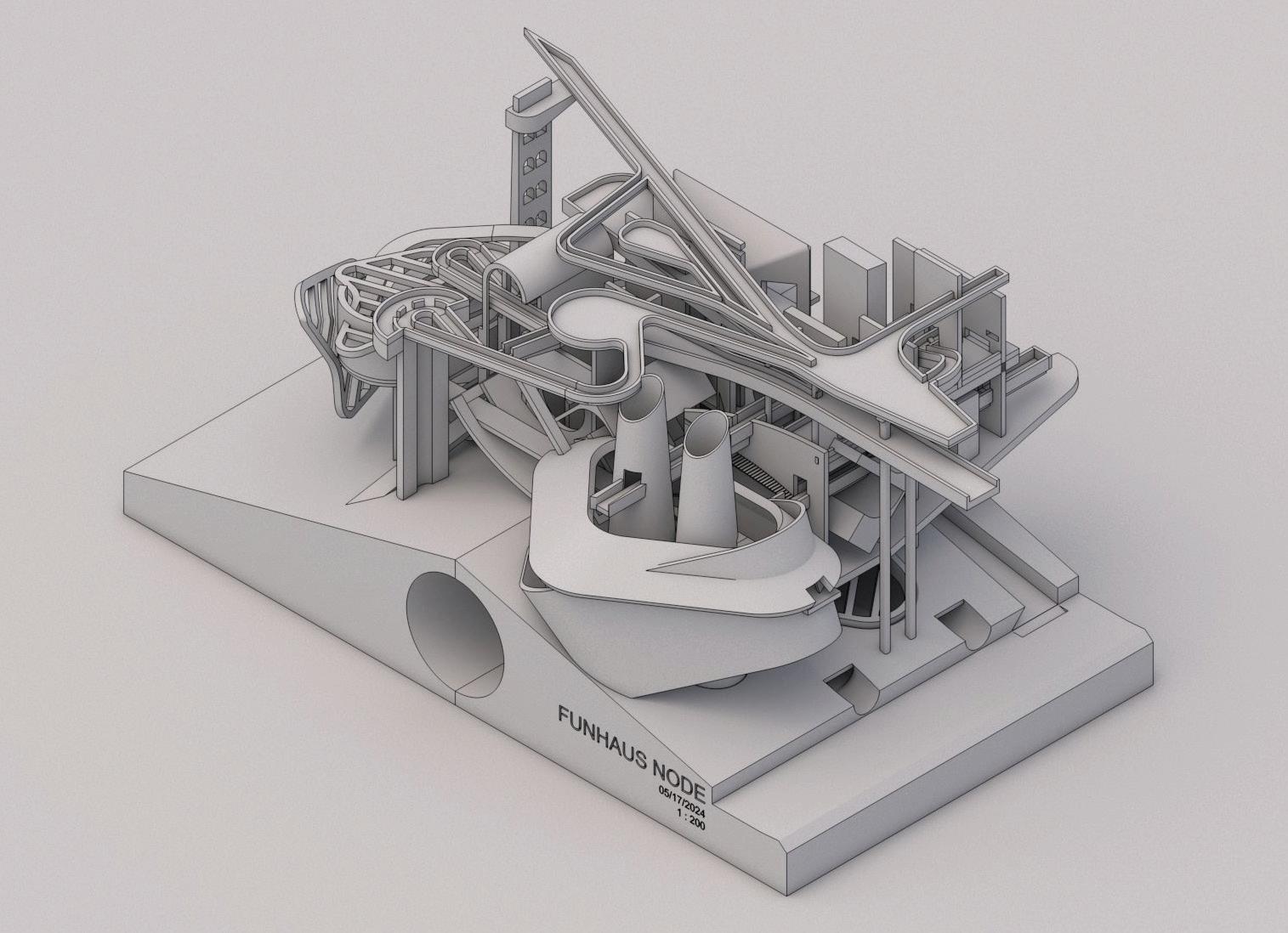

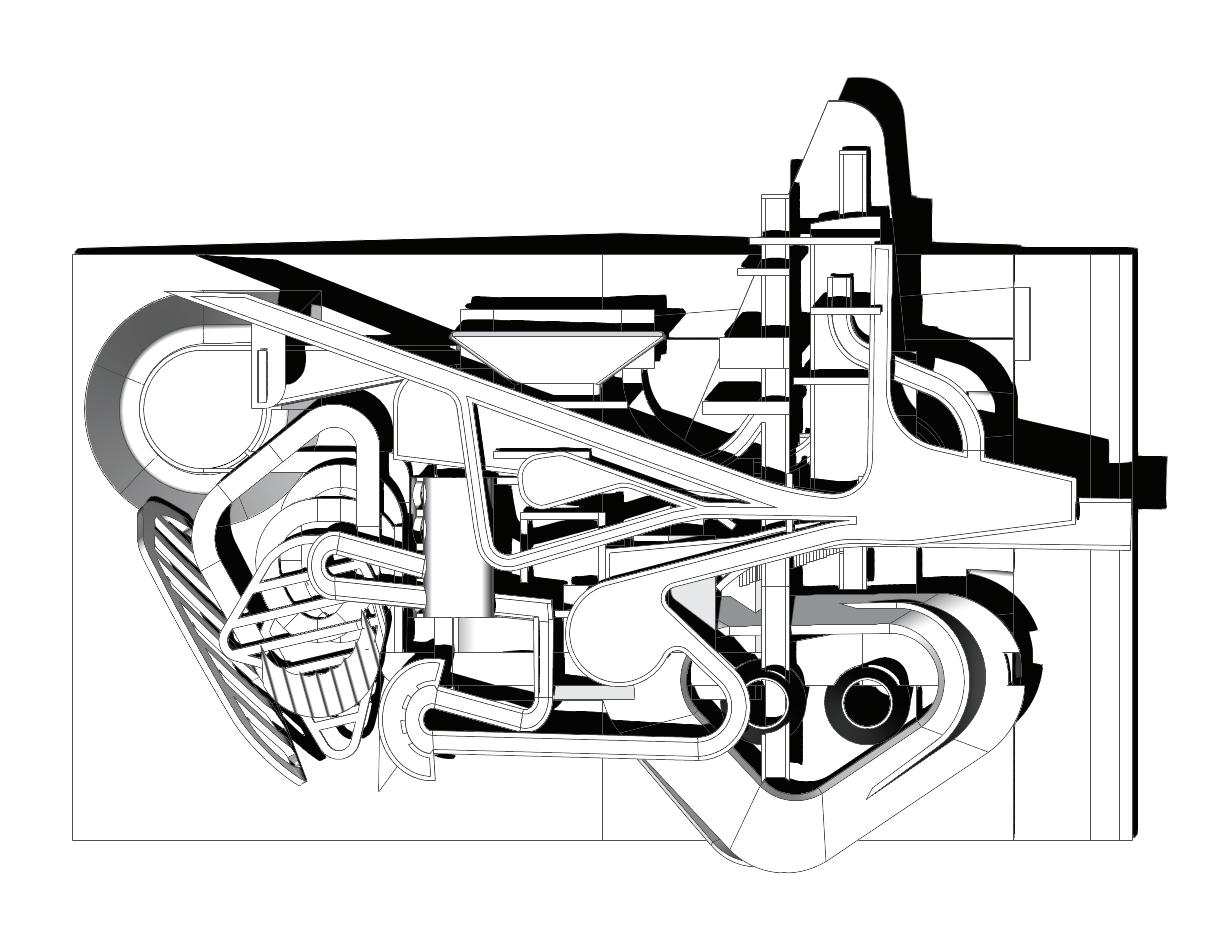

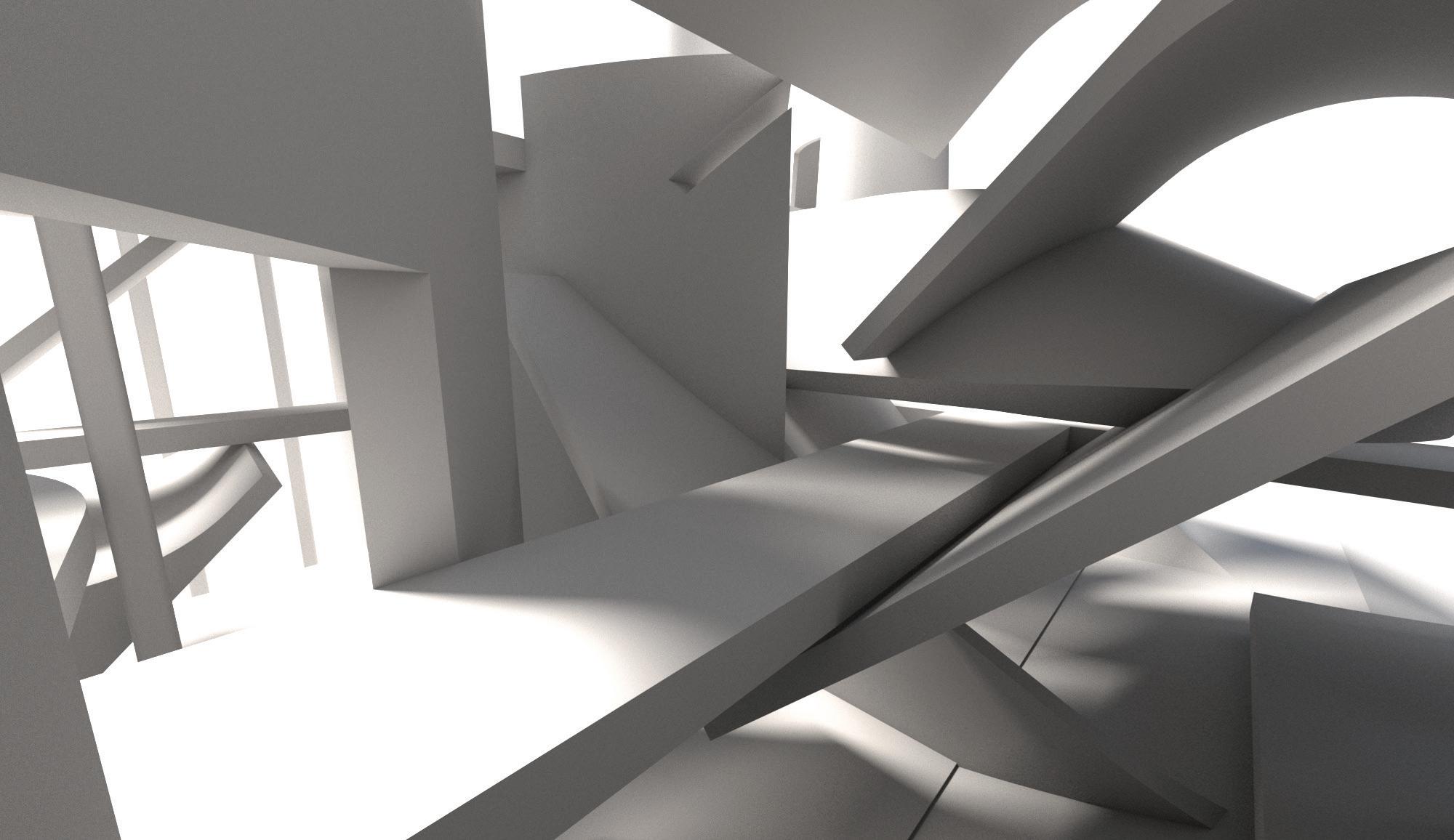

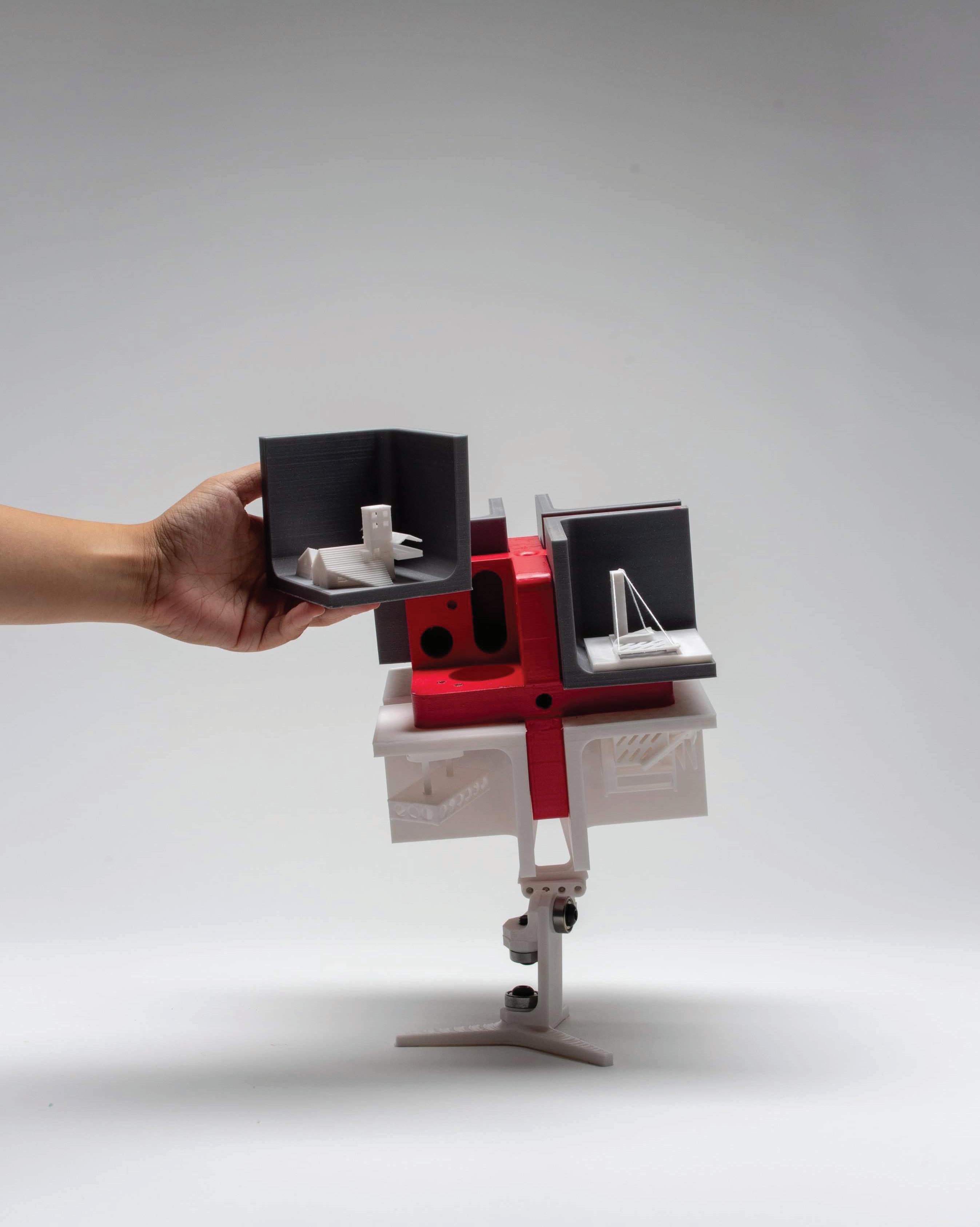

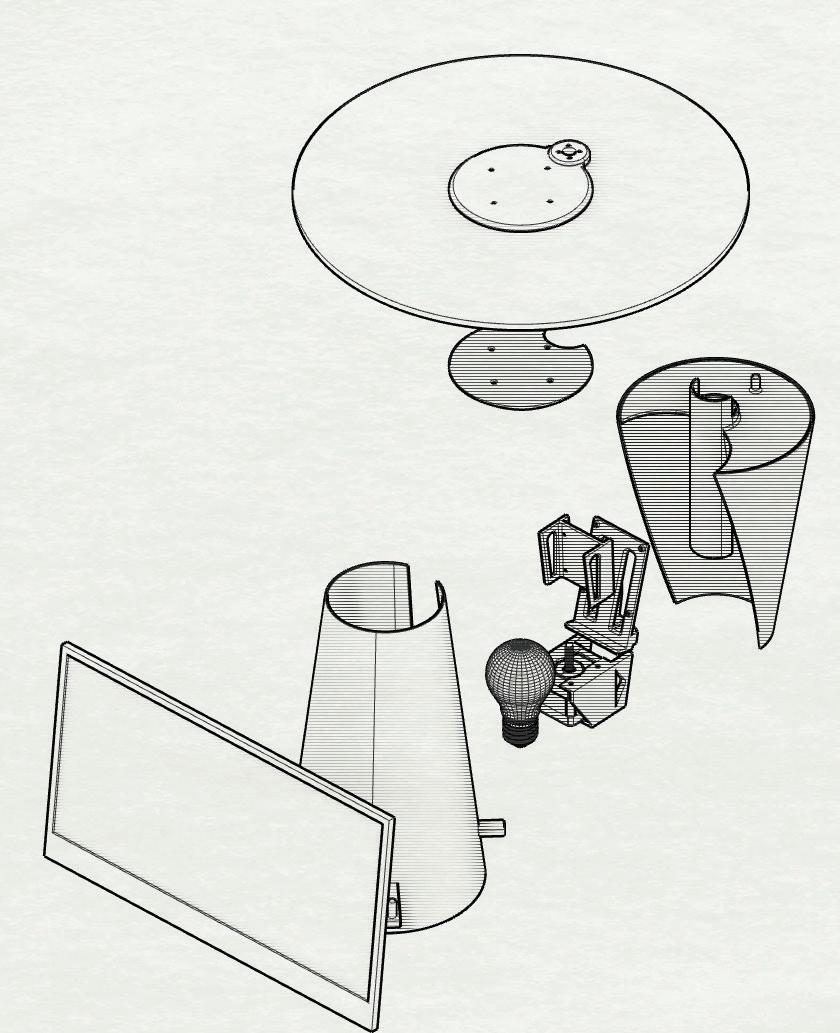

This framework begins from opposite ends of the spectrum of scale. First, this thesis introduces an urban-scale design framework that begins to facilitate the everyday routines of its inhabitants. Second, this thesis examines discomfort at the architectural scale Meeting in between, the architectural scale intervention integrates into the urban scale intervention as nodes. While both scales utilize discomfort as a design driver, the urban scale explores behavior/routine alteration and urban connectivity, while the architectural scale zooms in and examines unconventional walls, ceilings, floors, and paths.

Deriving ideas from Halprin’s RSVP cycles as well as Ellison and Leach’s On Discomfort and Pezeu-Massabuau’s A Philosophy of Discomfort this thesis is not simply arguing for a chaotic introduction of discomfort into our daily lives, but rather, it is a strategic and puzzle-like insertion, where the benefits of discomfort are leveraged and juxtaposed within the existing comfort

This is crucial to our present and future, as a stagnant population is one that is content and not actively solving issues and dealing with undesirable thoughts. Architecture that pacifies is dangerous, negligent, and unhealthy.

45 44 IV1DESIGN-OVERVIEW

IV1DESIGN-OVERVIEW

A TALE OF TWO SCALES

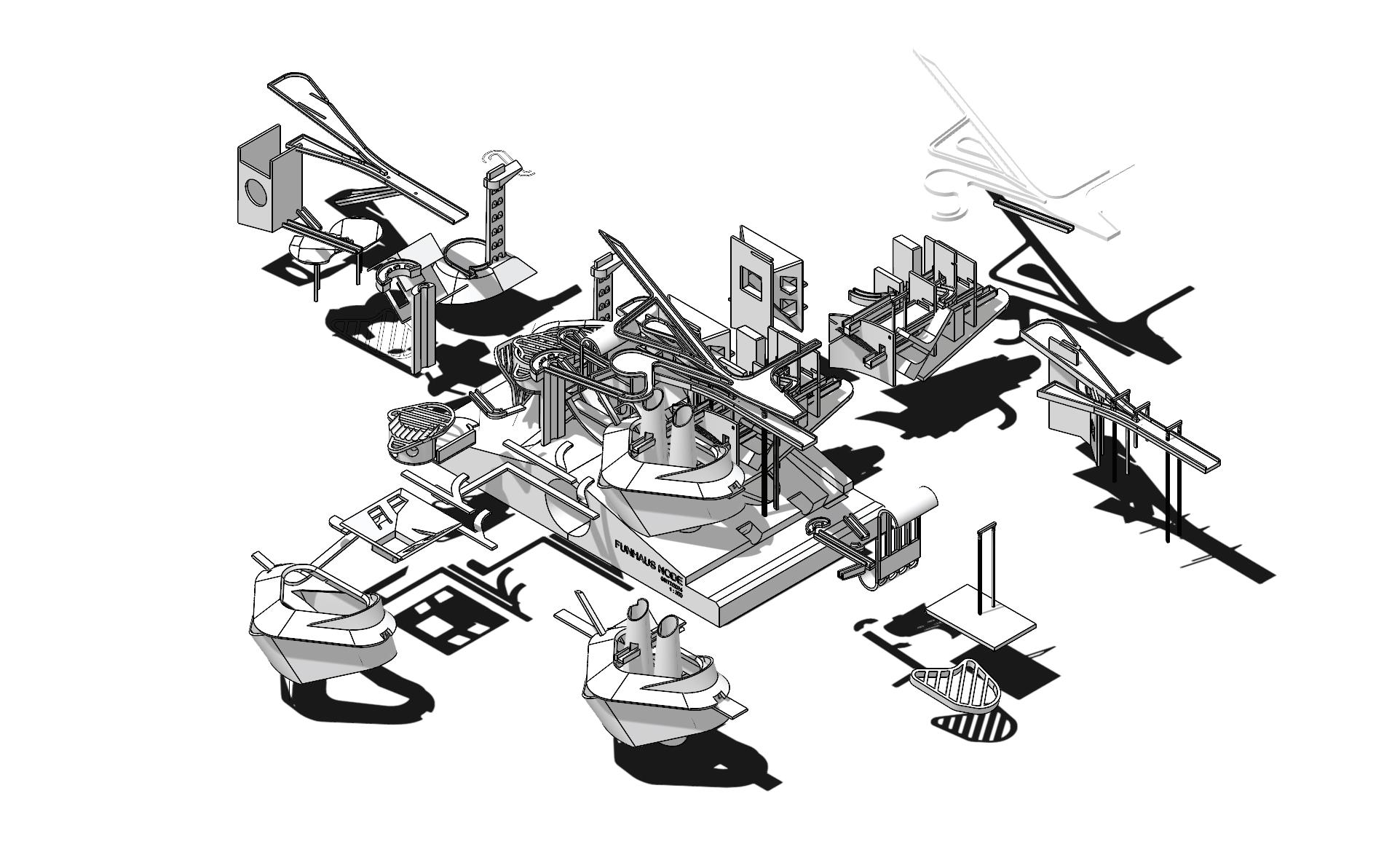

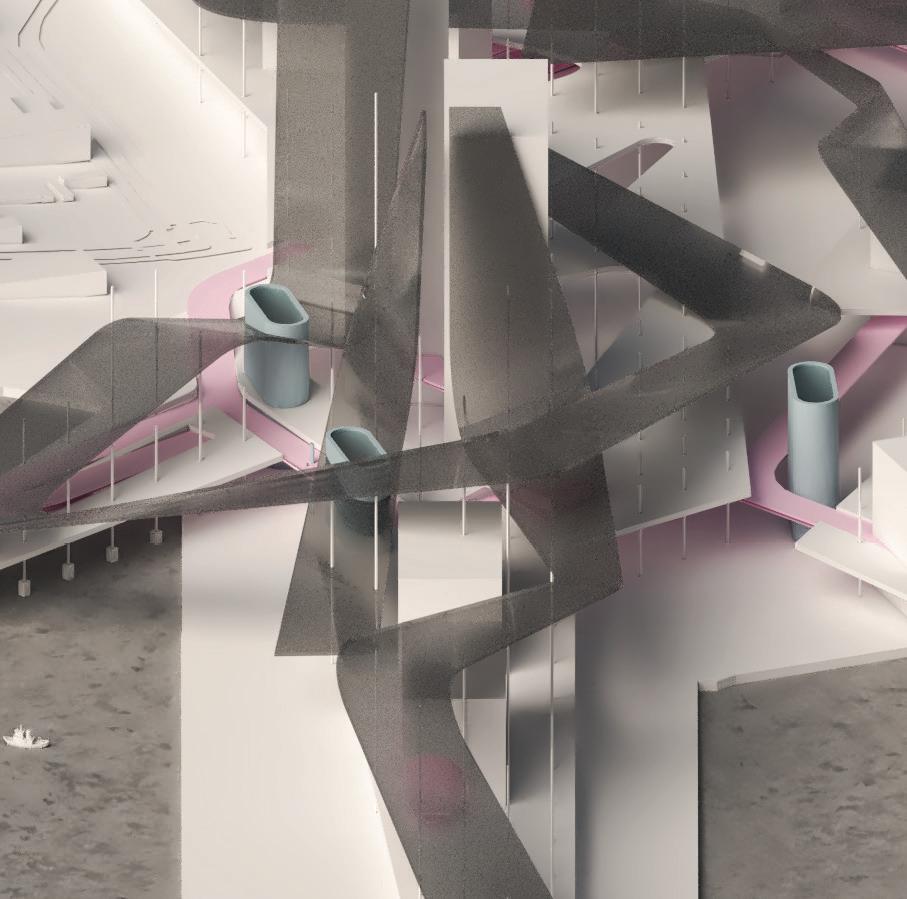

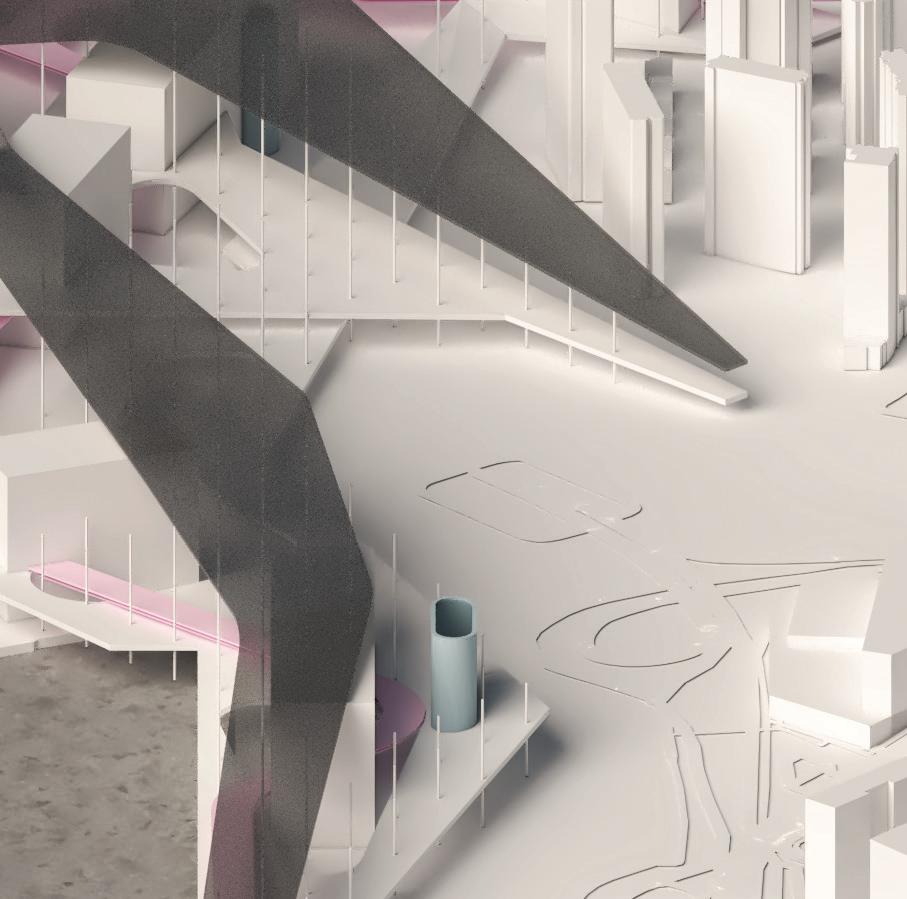

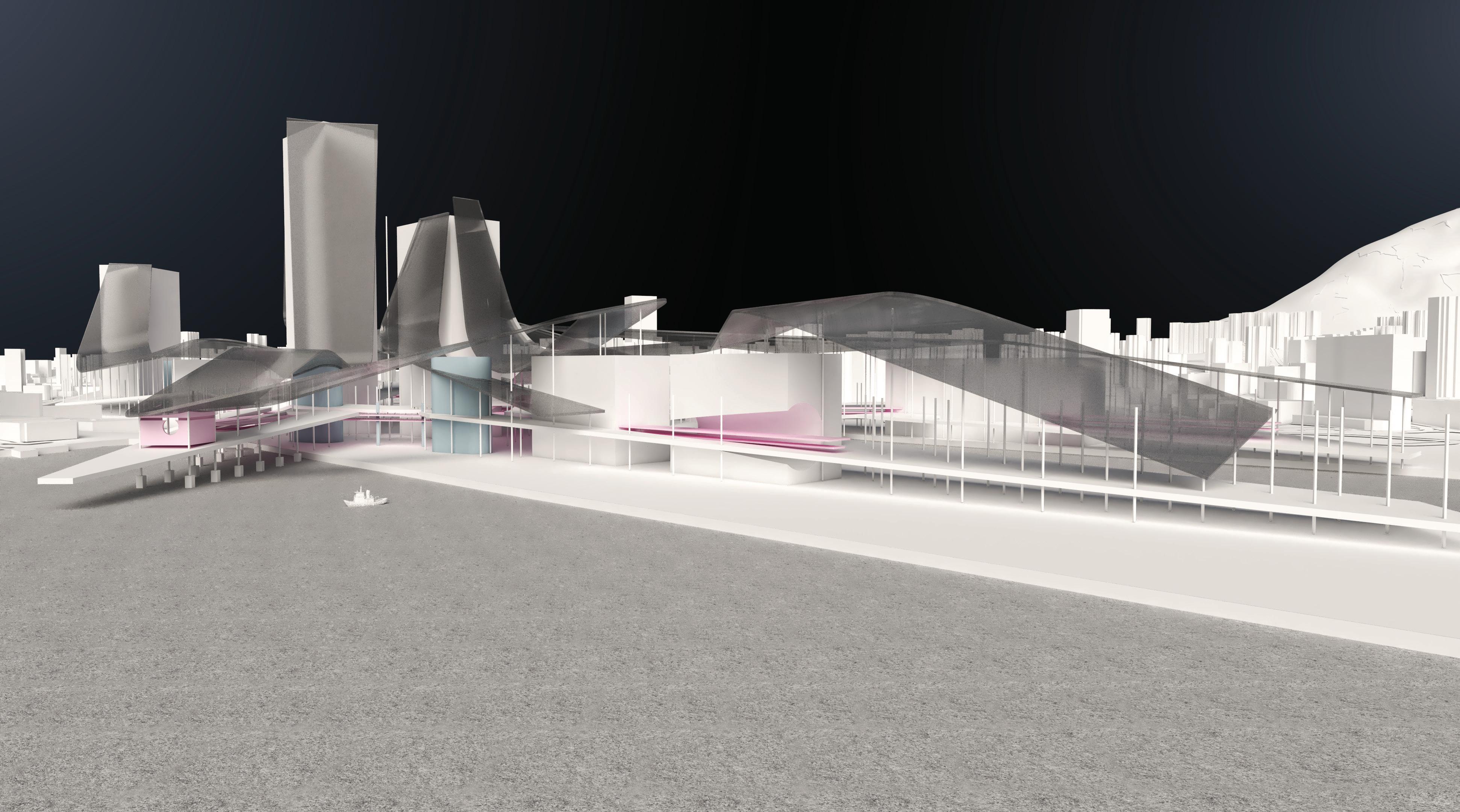

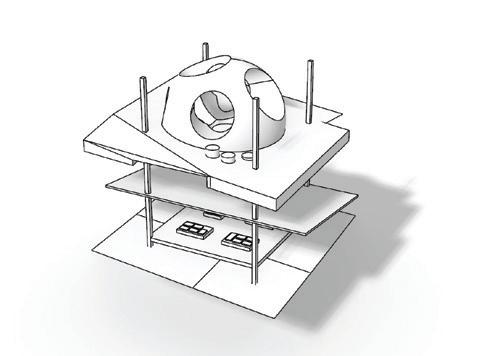

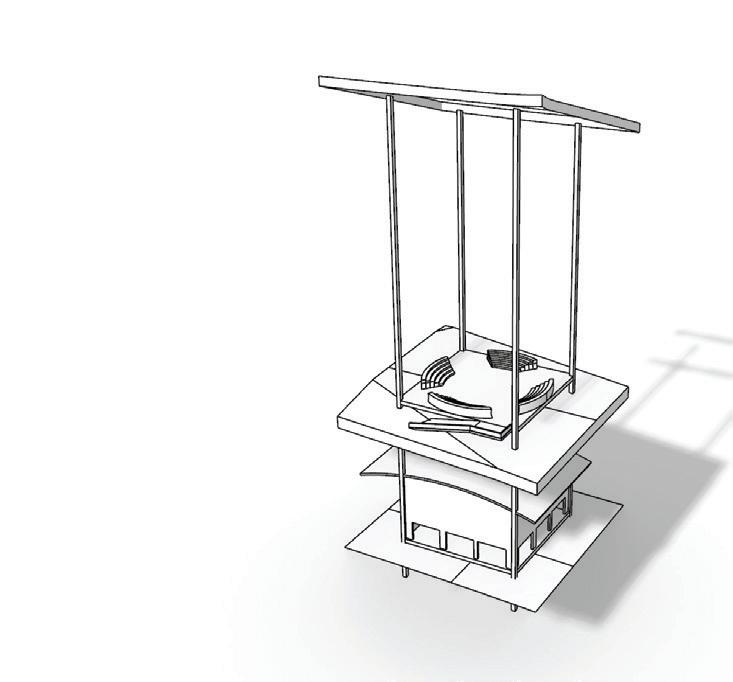

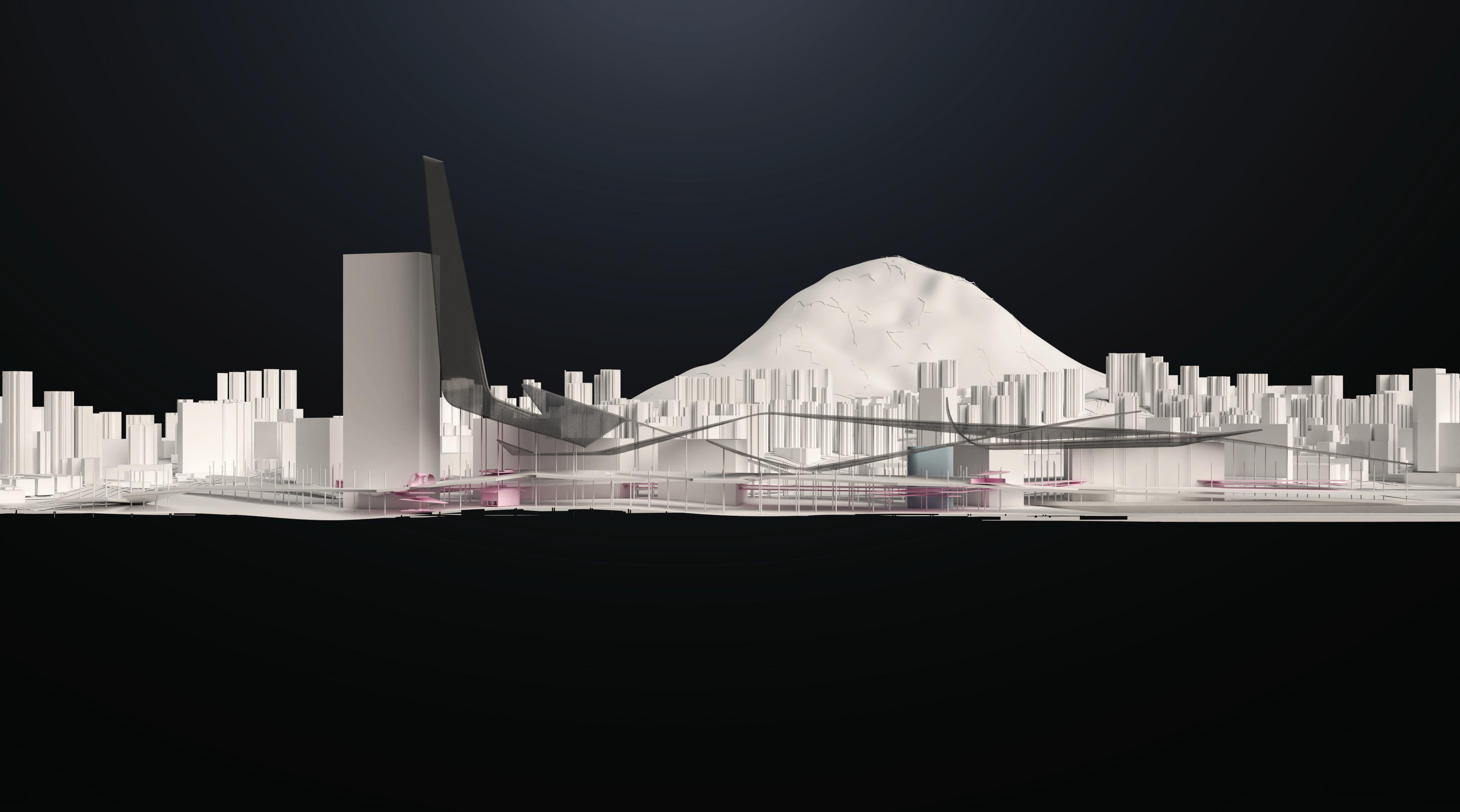

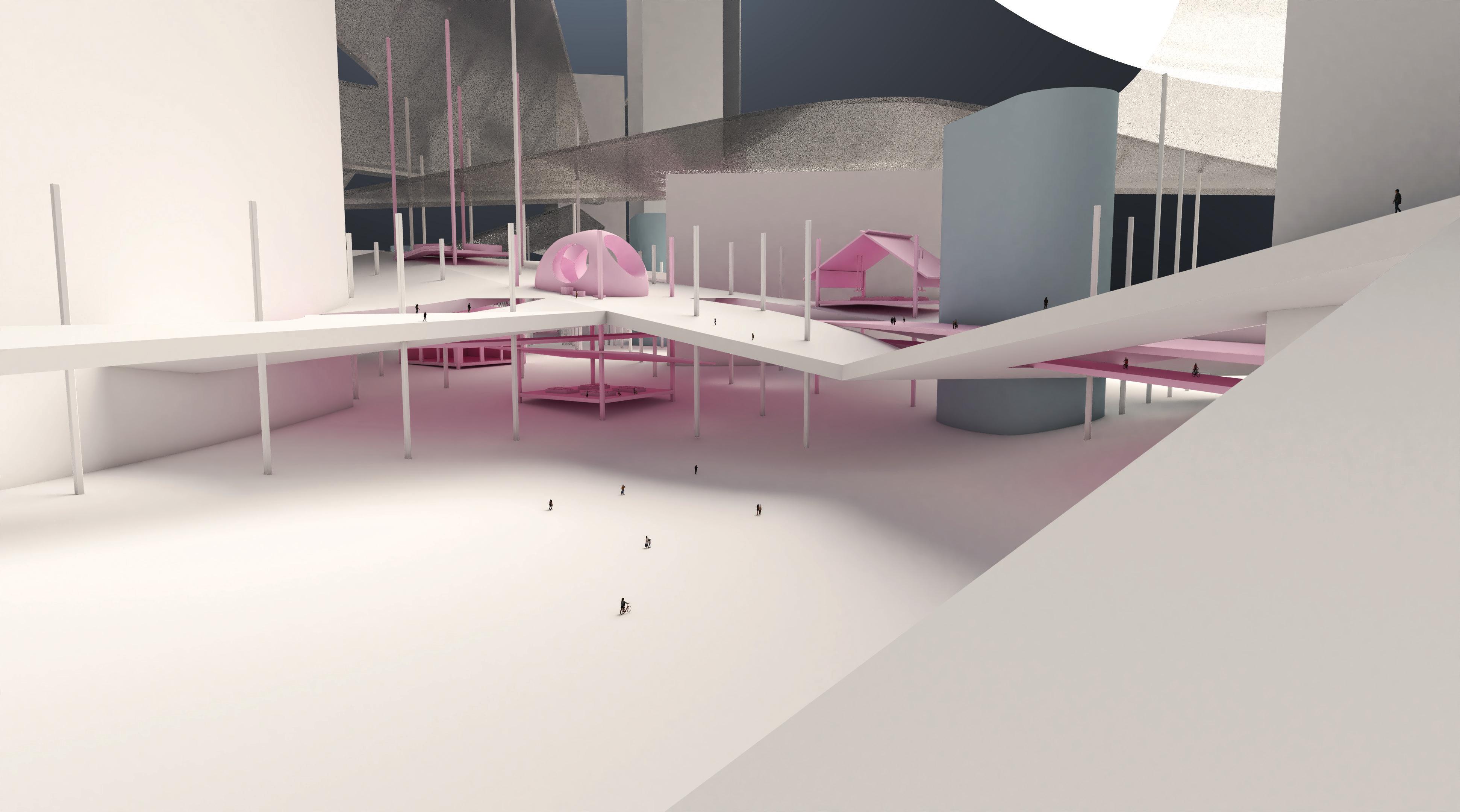

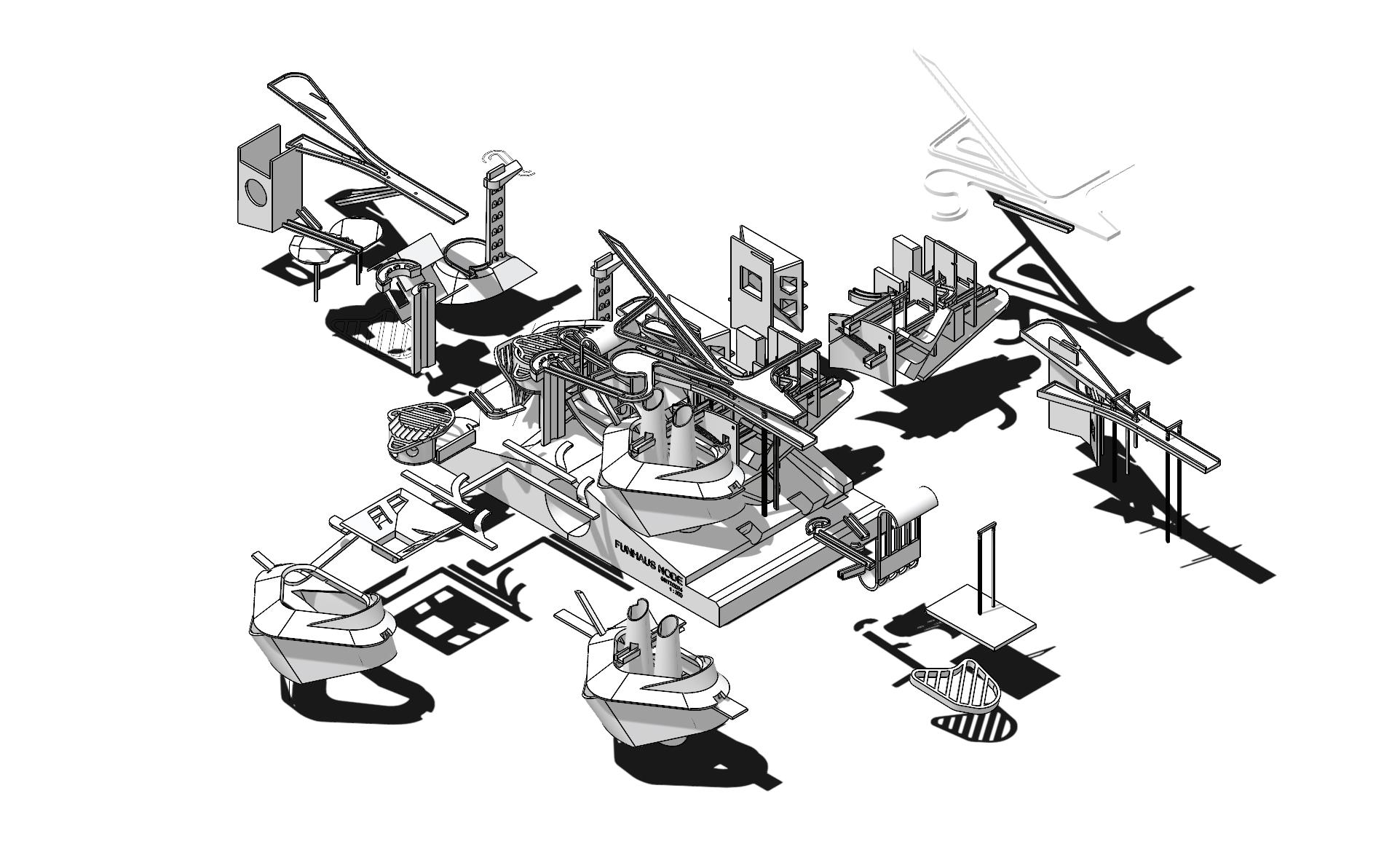

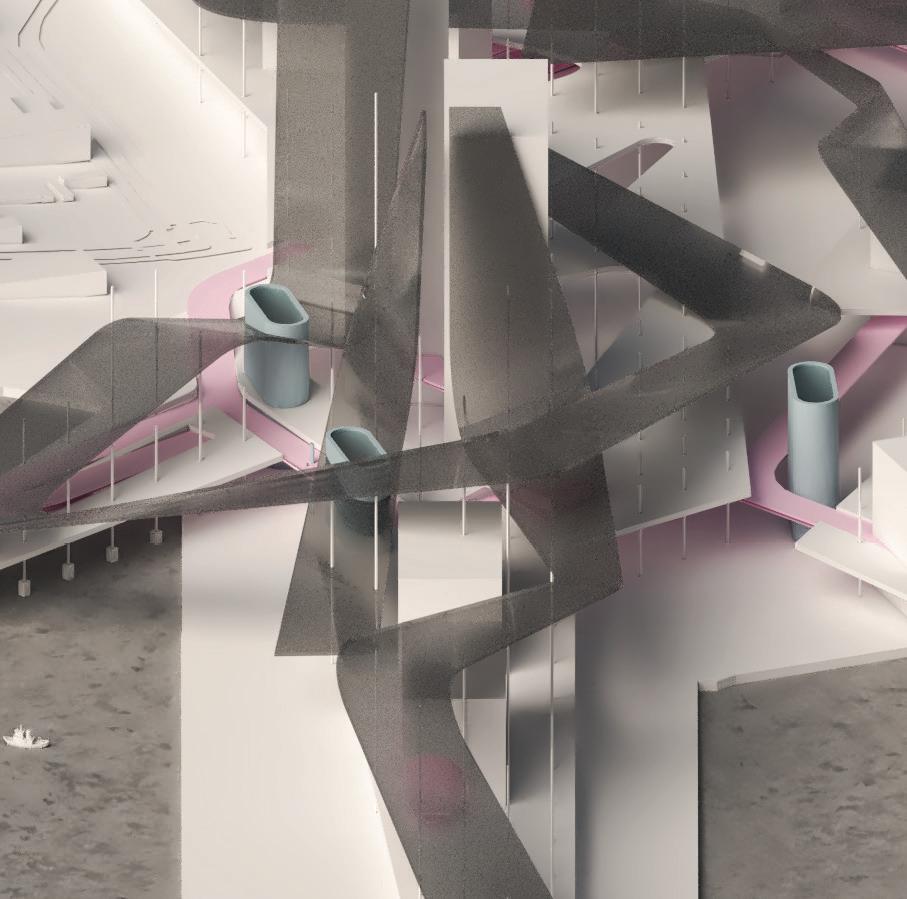

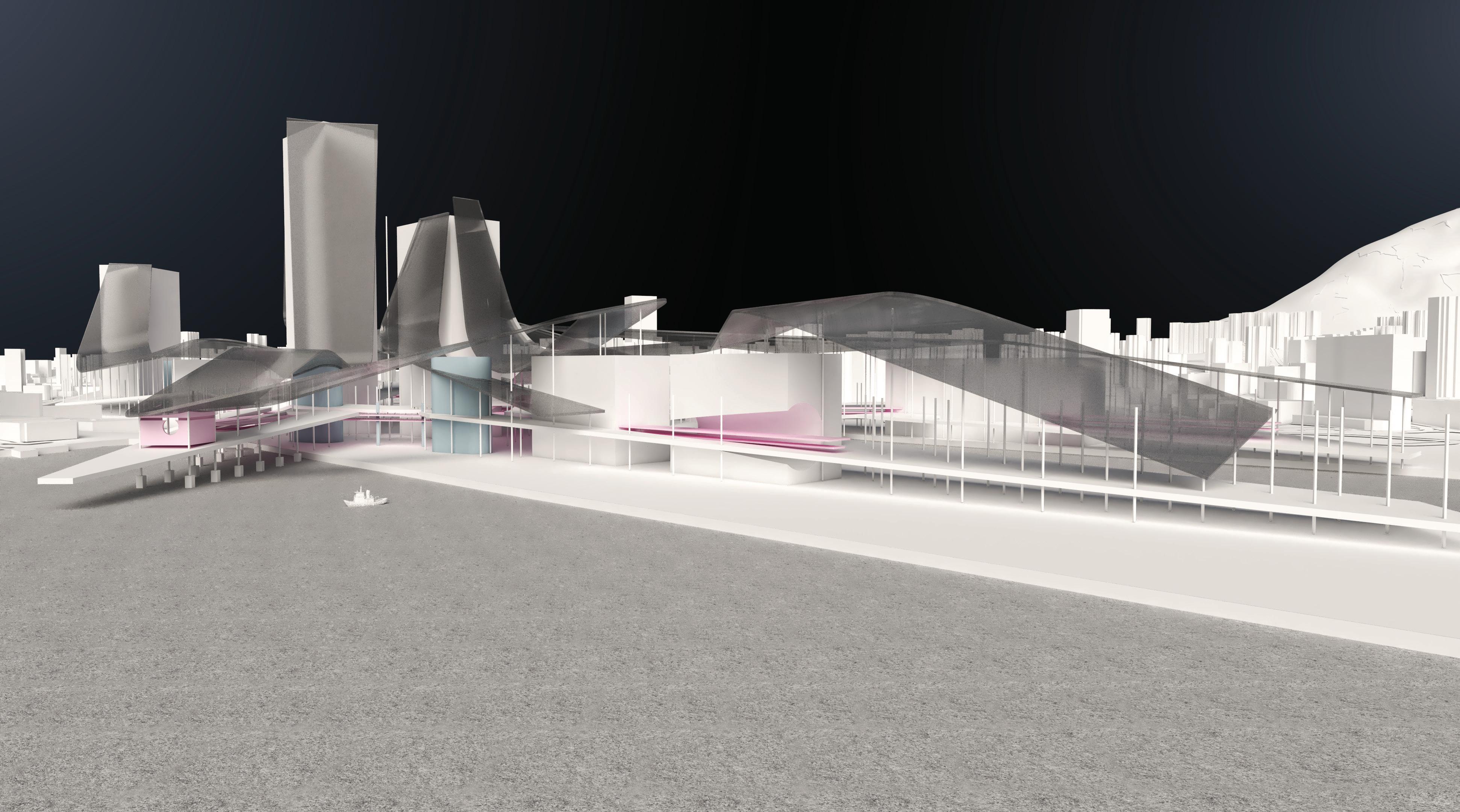

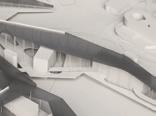

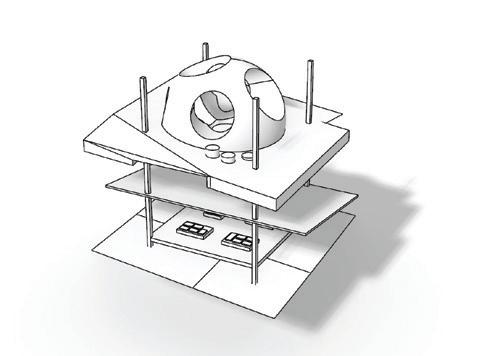

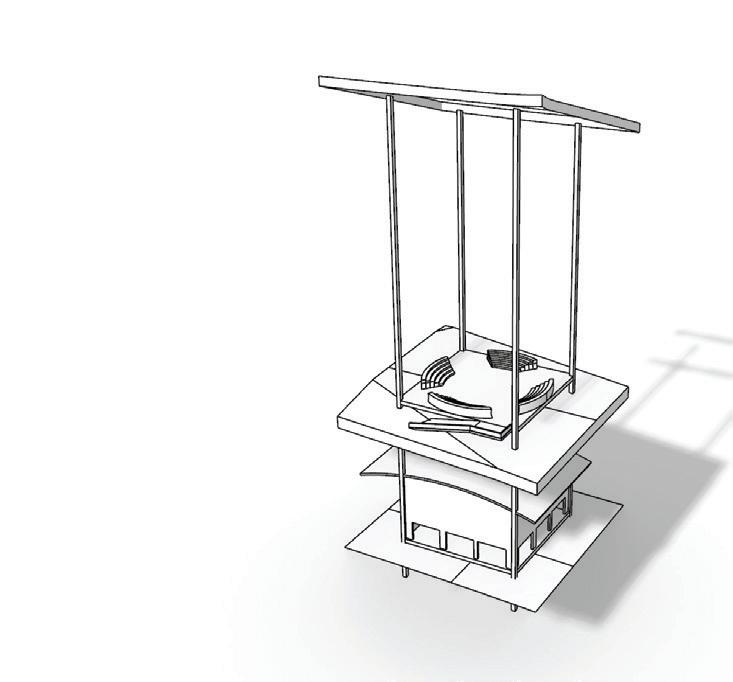

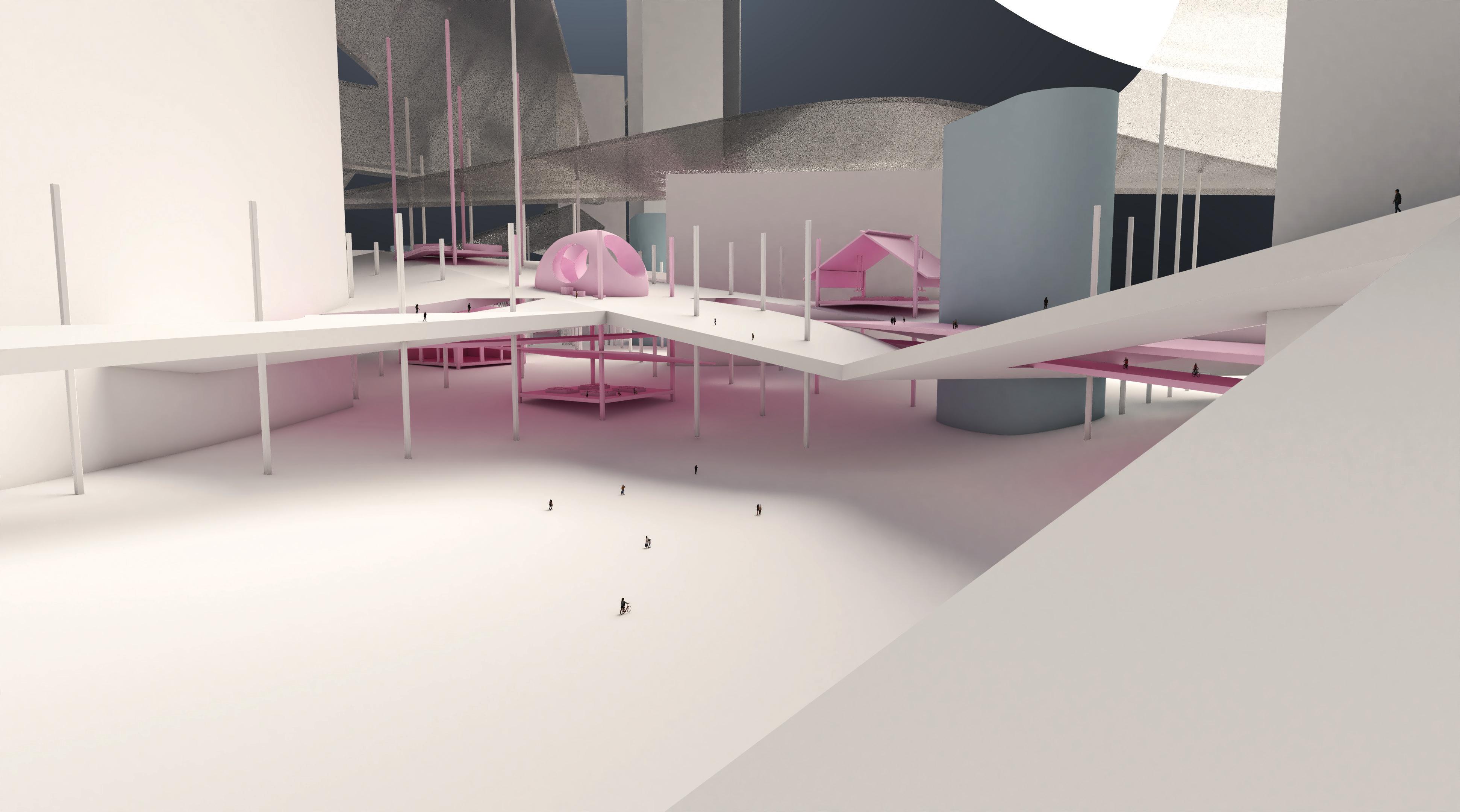

E-02 (Right, Top) Aerial Perspective of urban scale intervention

E-03 (Right, Bottom) Axonometric of architectural scale intervention

IV . 2 . PROCESS

Rather than take on the daunting task of altering the current design paradigm entirely, we can dissimulate existing entities and use them differently. The goal is to adopt a pavilionesque methodology to put forward radically novel ideas. When we cannibalize typologies, novelty is grounded in the existing, effectively ensuring the feasibility of the wildest imaginations ( poetic pragmatics ). The exploratory process involves testing how architecture can influence human behavior on different scales. Each output should investigate the symbiotic relationship between the built environment and its inhabitants in a nontraditional sense. The ultimate goal is to exploit the hybridization of comfort and discomfort and use it to perceptually shape ideologies. Within the confines of an organic conglomerate, investigate non-indexable qualities and how this form of “dwelling” could grow and transmute over time.

Geography/ Context/ Scale

A site should be perpetually amorphous so that it changes with the needs of its inhabitants and shifts with the values of the present. Using Corner’s plates and Turnbull’s non-indexical produces a more authentic look at the spatial and social aspects of Kowloon Walled City (KWC). By examining the growth and progression of KWC through its short existence, develop a framework of a site that serves more as a social experiment by combining ideas of discomfort and maternal nurturing in lieu of a classic mixed-use residential complex.

Users/ Time/ Spatial Organization

The spatial logic of space should cater to the collective first then the individual over time, and the inhabitants will also bear the responsibility of caring for the space. Nature is not a linear chain. The interconnected bubble diagram , though not a perfect diagram itself, can more accurately describe the different relationships between networks. The organic analogies hinted at by Le Corbusier turn

architecture into a “vital being” or machine, with many interworking parts. Architecture’s “direct intervention in human affairs” is ever-present and consequently provides a guide/framework for life, which includes the social aspects. Robin Evans suggests that the effect of architecture is similar to a lobotomy performed on society, with equal control in inspiring action and preventing action. Furthermore, patterns, as referenced by Christopher Alexander, have intrinsic logics, so use those in a novel manner to create a “machine” or social experiment that explores comfort and discomfort in unison. This framework should also require something from the user to begin to form a symbiotic relationship.

Tectonic/ Materiality/ Experience

Materiality and tectonics, like spatial organization and form, should reflect the experience of the inhabitant and serve as more than an aesthetic backdrop.

Decorative and superficial use of tectonics and materials limits engagement between the user and the built world. Favoring cultural significance in lieu of stylistic trends will always have more impact on creating a sense of place. This is one of the roles of the architect, and the consideration of context alone is not enough. Furthermore, the scale of tectonics is a powerful design factor that can apply meaning to the built environment. This thesis exists at the intersection between psychology and architecture but is ultimately derived from the experiential, which can be explored via unconventional uses of tectonics.

While sustainability through material use isn’t a main driver in this project, material use, and tectonic systems bear the responsibility of contributing to the discussion of minimizing negative impacts on our environment.

designs that are ergonomically comfortable puts users into a state of discomfort, but, importantly, not in crisis.

47 46

IV2PROCESS

IV2PROCESS METHODS TO THE MADNESS

E-04 (Above) The Modulor Man by Le Corbusier; meant as a universal system of proportions by referencing math, the human form, and architecture. Straying from universally accepted

E-05 (Above) Diamond House B, Projection by John Hejduk; This project explores the orthogonal system and the meaning of frontality. The relationship between walls and planes are highlighted and questioned.

IV . 3 . INTERVENTION

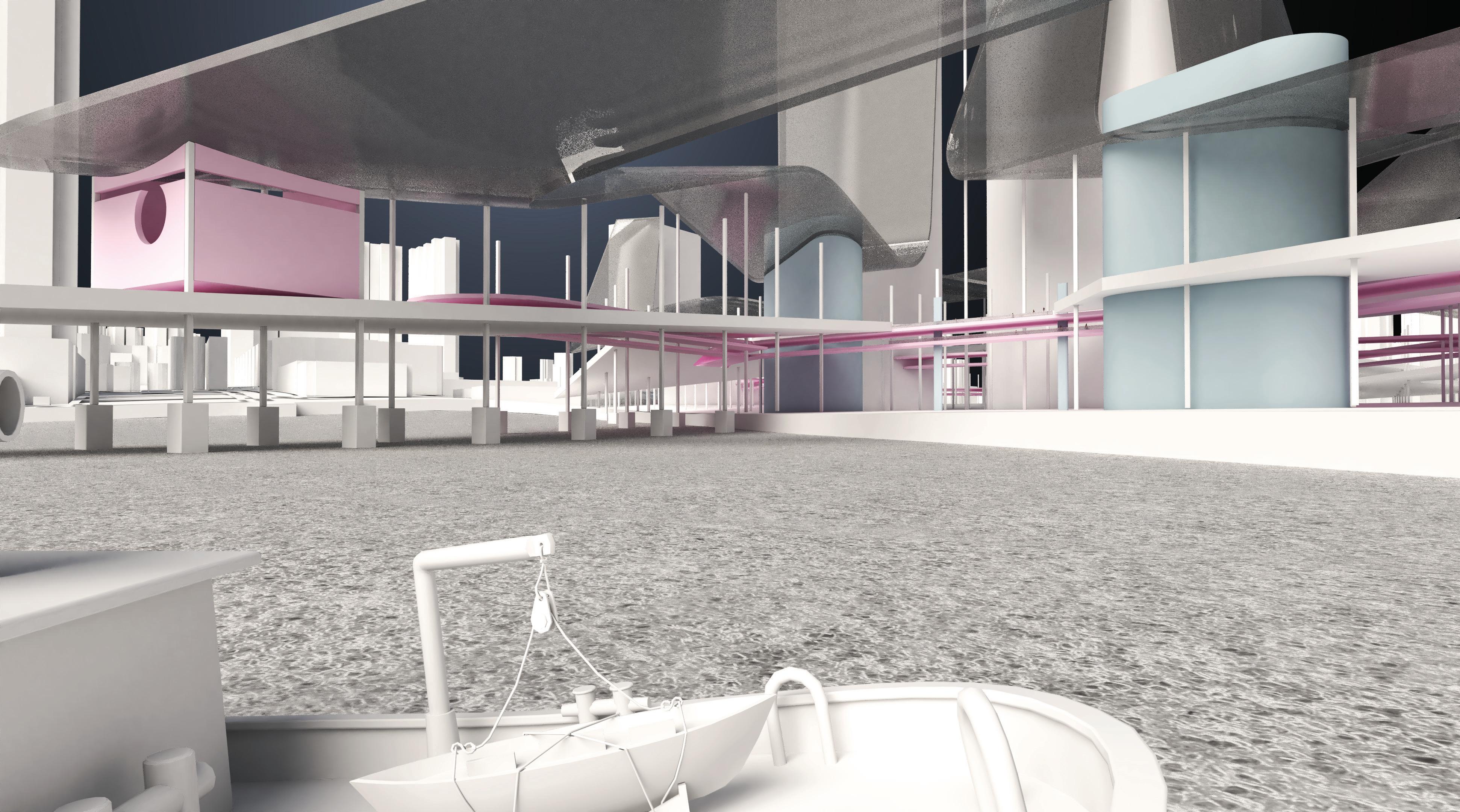

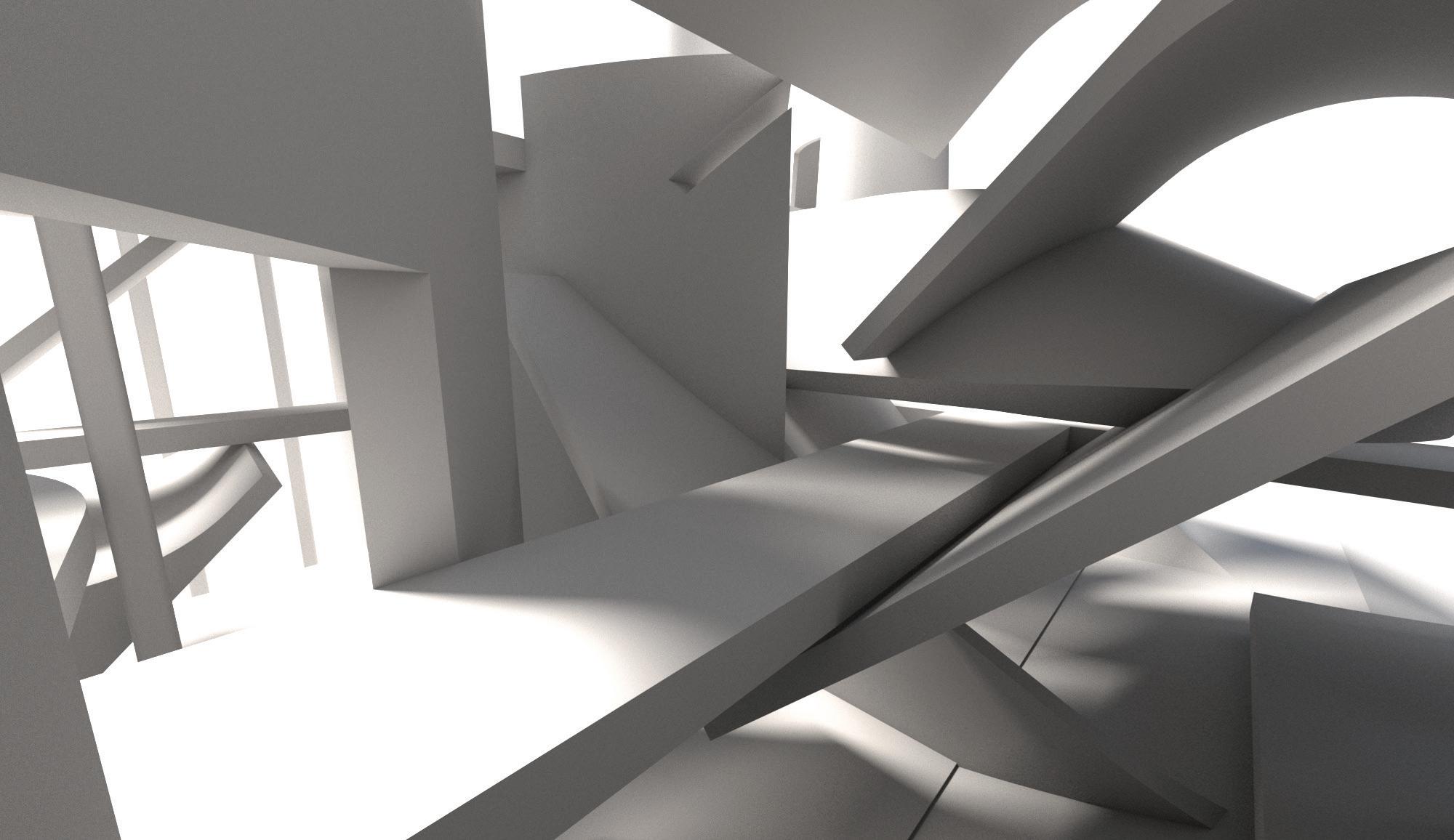

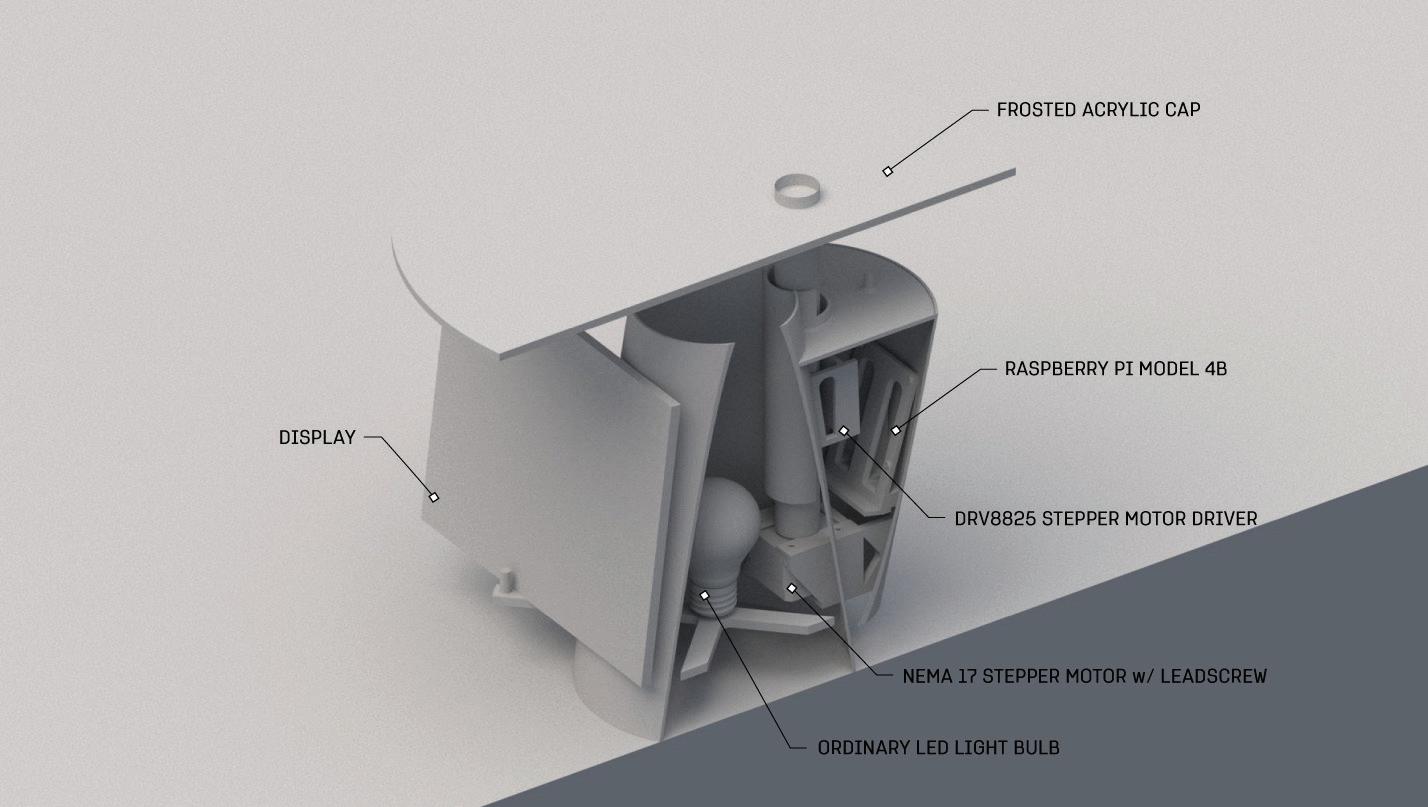

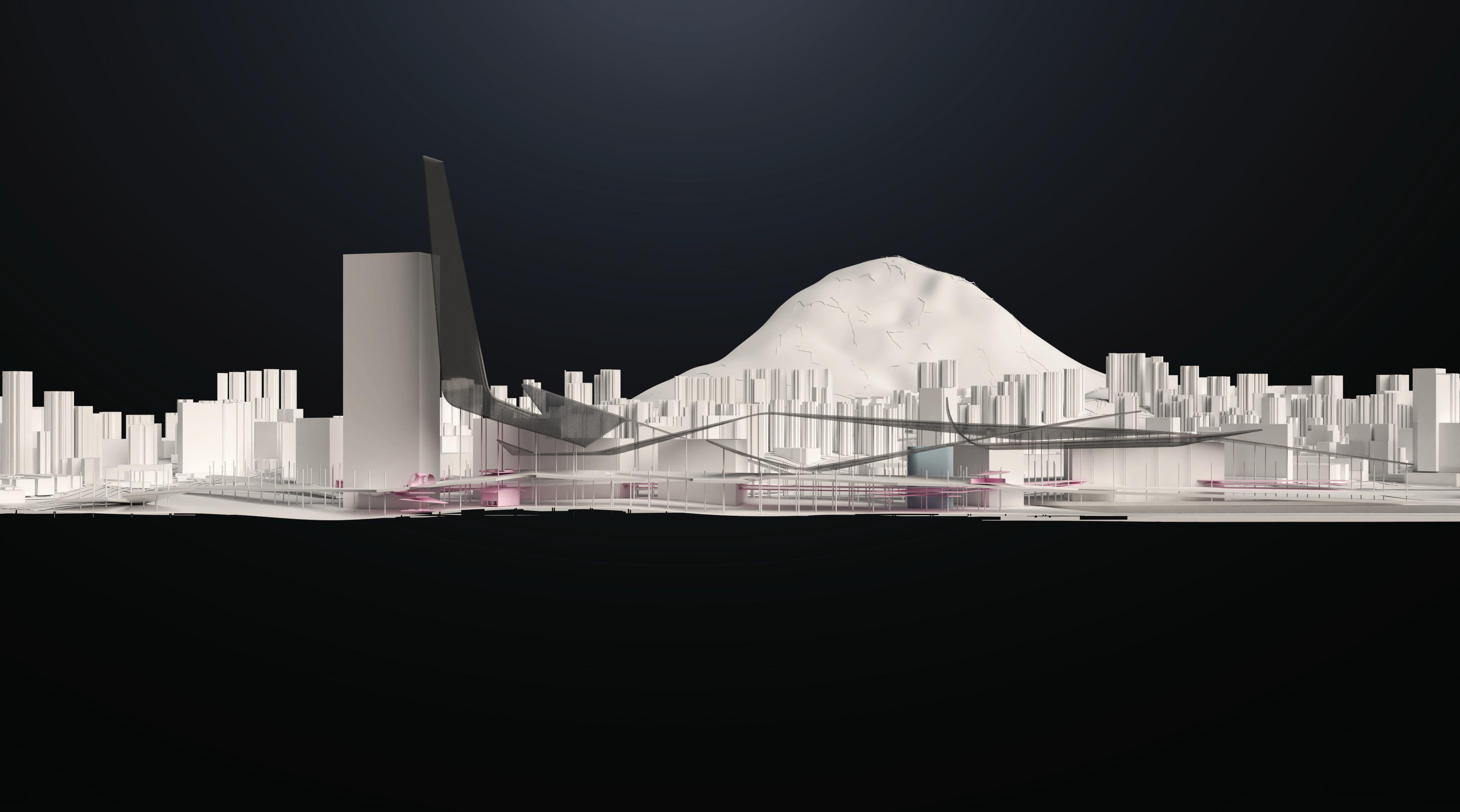

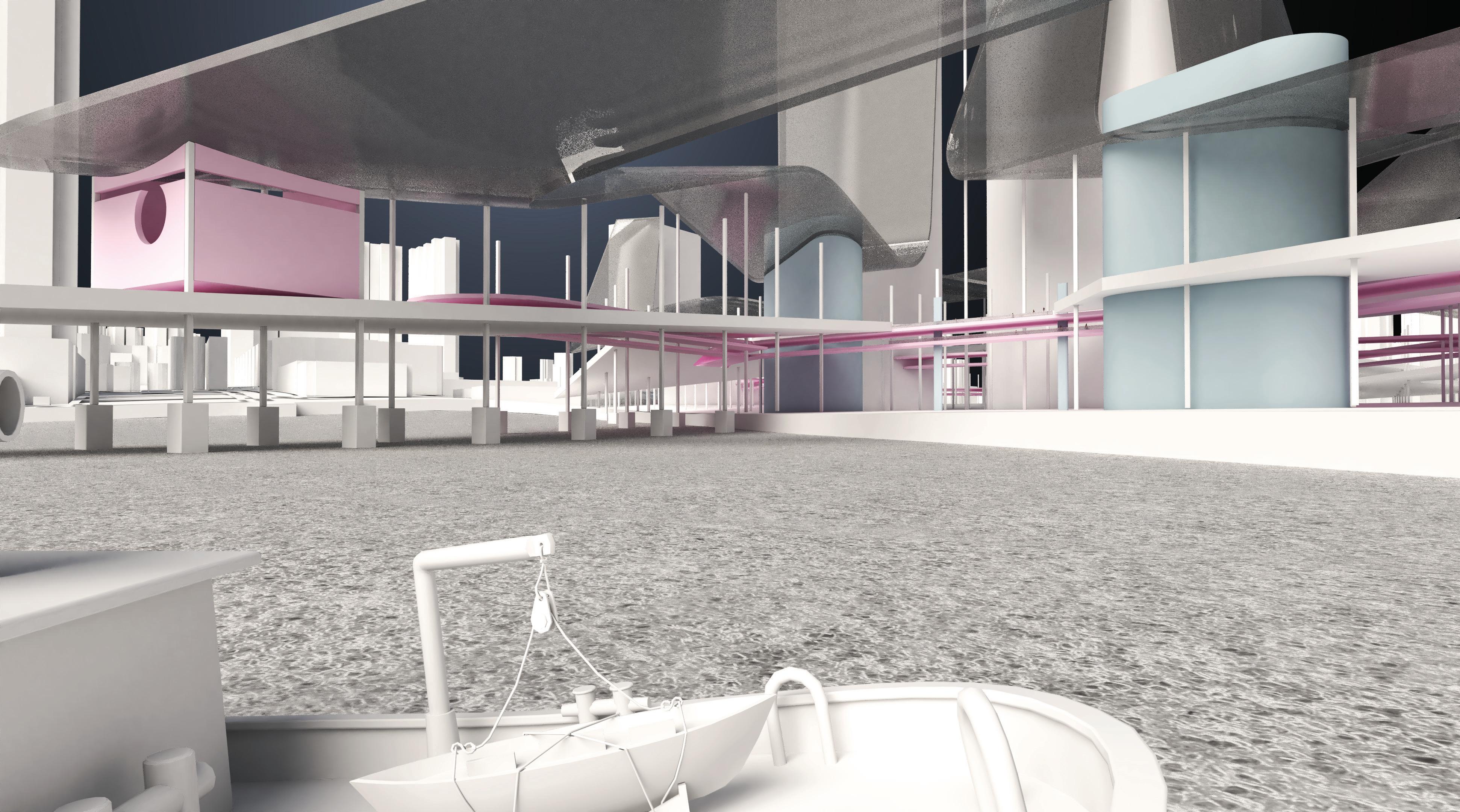

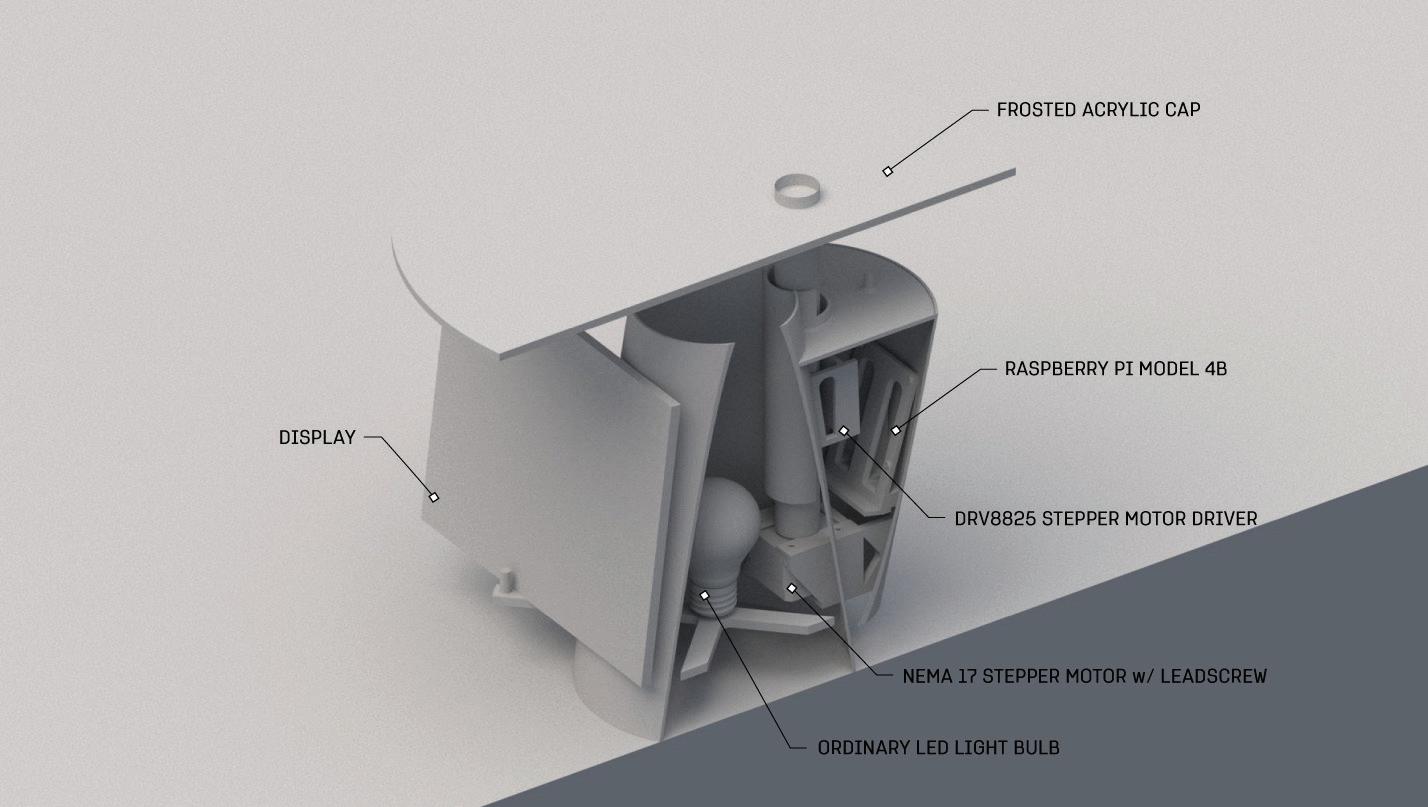

This thesis looks into the effect of architecture on the body and mind. Using slight discomfort and impermanence to disrupt the body and mind’s state of equilibrium/ homeostasis, a neuroplastic environment brings inhabitants into a heightened state of awareness and strengthens the relationship between user and architecture. In this urban-scale intervention, users partake in a systematic shift in their daily routines via a system of circulation paths, reflection nodes, berms, and an infrastructure of impermanence.

Taking influence from the logistics and principles of the original Kowloon Walled City, a city that grew from a refugee camp into a dense organic megastructure, this intervention is a two-pronged approach that first asks inhabitants to adopt a behavioral and routine change that takes advantage of discomfort to bring users into mindfulness. Second, this intervention proposes an infrastructural system that fosters user adaptation through a market hall typology manifested by the berm and the cadence of the columns.

49 48

IV3INTERVENTION

DR. LEBBEUS WOOD OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE DISCOMFORT

E-06 (Above) Aerial perspective of urban-scale intervention