3 minute read

Meet Yayoi Kusama, high priestess of polka dots. BY MITALI ROUTH

from INDY Week 2.19.20

by Indy Week

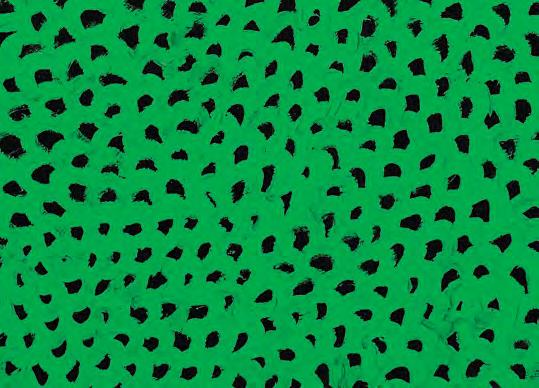

Detail from an untitled 1967 painting by Yayoi Kusama PHOTO COURTESY OF THE COLLECTION OF JAMES KEITH BROWN AND ERIC DIEFENBACH

The High Priestess of Polka Dots

The art of Yayoi Kusama beyond her spectacular mirrored rooms at the Ackland

BY MITALI ROUTH arts@indyweek.com

Yayoi Kusama’s impact on the art of the past century is incontrovertible. An enigmatic pioneer in the 1960s New York avant-garde whose influence can be observed in the work of Joseph Cornell, Donald Judd, and Andy Warhol, Kusama returned to her native Japan in the early ‘70s and eventually checked into a full-time psychiatric-treatment facility, where she has continued to live and work ever since.

From the ‘70s until the late ‘90s, little attention was paid to Kusama outside of Japan. In recent decades, renewed international interest has largely focused on her wildly popular “infinity mirrors,” which consist of kaleidoscopic mirrored surfaces and lights that viewers either peer into or enter. NCMA bought one for its permanent collection and unveiled it in the exhibit You Are Here in 2018. But Kusama’s long and prolific career includes everything from drawing, painting, and sculpture to poetry, performance, and film. Open the Shape Called Love, a new exhibit at UNC’s Ackland Art Museum, presents 22 artworks, created between the ‘50s and the ‘00s, from this lesser-known side of Kusama. It’s a subtle, understated introduction to one of the world’s most important living artists, though it struggles to tell a cohesive story about her multifaceted work.

The exhibit’s title comes from one of Kusama’s poems: “Open the shape called Love,” she writes. “I want to return to the earth.” The words inevitably bring death to mind, but at almost 91, she knows something about survival.

Kusama is a self-identified “obsessional artist,” and critics have often emphasized her struggles with mental illness.

“Painting saved my life,” she has said. “I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and art is the only method I have found to relieve my illness.” In the wall text and catalog that frame the show, the Ackland is preoccupied with this self-therapeutic aspect, focusing heavily on artist’s reported hallucinations and outlining what the museum terms her three-pronged approach to “managing [her mental] condition, expressing that condition, and transcending that condition.”

But Kusama’s concerns as an artist extend far beyond herself, toward an ever-evolving philosophical investigation in which the self is a kind of conceptual substrate of the cosmos.

“My momentary life, that is supported by some invisible force, exists in a brief moment of quietude amidst hundreds of millions of endless light years,” she has said. In failing to flesh out the visual and conceptual considerations of the cosmos in Kusama’s paintings, the exhibit eclipses her philosophical interests with a story about her psychic unraveling. Though it touts her “acute sensitivity to the cultural moment [of the 1970s],” it doesn’t sufficiently expand on her traumatic historical context—growing up in the shadow of the U.S.’s atomic bombing of Japan, for example—or adequately situate the artist among her avant-garde contemporaries.

Either approach would have made the attempt to connect Open the Shape Called Love to ancillary exhibit Toriawase: A Special Installation of Modern Japanese Art and Ceramics more constructive. “Toriawase,” meaning to choose and combine objects with care, is practiced in Japanese tea ceremonies. While the works in the small exhibit are exquisite, the association with Kusama is loose, seemingly limited to shared national origin rather than conceptual, historical, or other intersections that are implied but never fully illuminated.

More than a story of mental illness, the works at the Ackland convey ideas about the infinite. The scale is intimate; you can imagine the self-appointed “High Priestess of Polka Dots” making them privately, meticulously, in a small studio, away from the rest of the world. Most striking are her “Infinity Net” paintings, in which Kusama explores form as something at once ordered and chaotic, contained and infinitely reproducible, and always prone to dissipation. Her networks of dots and other organic shapes seem to extend beyond their small frames.

This resonates with Kusama’s obsessive exploration of the self as something that dissolves and repeats—something that tends toward obliteration.

“Forget yourself,” she has said. “Become one with eternity. Become one with your environment.”

Kusama’s infinity mirrors captivate us through the drama of light, scale, and reflection, but their very popularity often restricts our engagement to selfies. They are hardly sites for contemplating Kusa ma’s questions about the conflicts between truth and illusion.

But such revelations are possible in the Ackland’s exhibit, where Kusama’s tender obsessiveness looks less like evidence of psychological precarity, as the museum would have it, and more like the method and theory of a sustained artistic inquiry. W